From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrous_oxide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Nitrous oxide (not recommended)

Dinitrogen oxide (alternative name) | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Oxodiazen-2-ium-1-ide | |

| Other names

Laughing gas, sweet air, nitrous, nos, protoxide of nitrogen, hyponitrous oxide, dinitrogen oxide, dinitrogen monoxide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 8137358 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.017 |

| E number | E942 (glazing agents, ...) |

| 2153410 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1070 (compressed) 2201 (liquid) |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

|---|---|

| N 2O | |

| Molar mass | 44.013 g/mol |

| Appearance | colourless gas |

| Density | 1.977 g/L (gas) |

| Melting point | −90.86 °C (−131.55 °F; 182.29 K) |

| Boiling point | −88.48 °C (−127.26 °F; 184.67 K) |

| 1.5 g/L (15 °C) | |

| Solubility | soluble in alcohol, ether, sulfuric acid |

| log P | 0.35 |

| Vapor pressure | 5150 kPa (20 °C) |

| −18.9·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.000516 (0 °C, 101,325 kPa) |

| Viscosity | 14.90 μPa·s |

| Structure | |

| linear, C∞v | |

| 0.166 D | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

219.96 J/(K·mol) |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

+82.05 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| N01AX13 (WHO) | |

| Inhalation | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| 0.004% | |

| 5 minutes | |

| Respiratory | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Nonflammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Ilo.org, ICSC 0067 |

| Related compounds | |

| Nitric oxide Dinitrogen trioxide Nitrogen dioxide Dinitrogen tetroxide Dinitrogen pentoxide | |

Related compounds

|

Ammonium nitrate Azide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

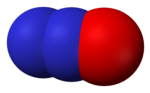

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide), commonly known as laughing gas, nitrous, or nos, is a chemical compound, an oxide of nitrogen with the formula N

2O. At room temperature, it is a colourless non-flammable gas, and has a slightly sweet scent and taste. At elevated temperatures, nitrous oxide is a powerful oxidiser similar to molecular oxygen.

Nitrous oxide has significant medical uses, especially in surgery and dentistry, for its anaesthetic and pain-reducing effects. Its colloquial name, "laughing gas", coined by Humphry Davy, is due to the euphoric effects upon inhaling it, a property that has led to its recreational use as a dissociative anaesthetic. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is also used as an oxidiser in rocket propellants, and in motor racing to increase the power output of engines.

Nitrous oxide's atmospheric concentration reached 333 parts per billion (ppb) in 2020, increasing at a rate of about 1 ppb annually. It is a major scavenger of stratospheric ozone, with an impact comparable to that of CFCs. Global accounting of N

2O sources and sinks over the decade ending 2016 indicates that about 40% of the average 17 TgN/yr (teragrams of nitrogen per year) of emissions originated from human activity, and shows that emissions growth chiefly came from expanding agriculture and industry sources within emerging economies. Being the third most important long-lived greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide also substantially contributes to global warming.

Nitrous oxide is used as a propellant, and has a variety of applications from rocketry to making whipped cream. It is used as a recreational drug for its potential to induce a brief "high"; most recreational users are unaware of its neurotoxicity and potential to cause neurological damage.

Uses

Rocket motors

Nitrous oxide may be used as an oxidiser in a rocket motor. It has advantages over other oxidisers in that it is much less toxic, and because of its stability at room temperature it is also easier to store and relatively safe to carry on a flight. As a secondary benefit, it may be decomposed readily to form breathing air. Its high density and low storage pressure (when maintained at low temperature) enable it to be highly competitive with stored high-pressure gas systems.

In a 1914 patent, American rocket pioneer Robert Goddard suggested nitrous oxide and gasoline as possible propellants for a liquid-fuelled rocket. Nitrous oxide has been the oxidiser of choice in several hybrid rocket designs (using solid fuel with a liquid or gaseous oxidiser). The combination of nitrous oxide with hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene fuel has been used by SpaceShipOne and others. It also is notably used in amateur and high power rocketry with various plastics as the fuel.

Nitrous oxide also may be used in a monopropellant rocket. In the presence of a heated catalyst, N

2O will decompose exothermically into nitrogen and oxygen, at a temperature of approximately 1,070 °F (577 °C).

Because of the large heat release, the catalytic action rapidly becomes

secondary, as thermal autodecomposition becomes dominant. In a vacuum

thruster, this may provide a monopropellant specific impulse (Isp) of as much as 180 s. While noticeably less than the Isp available from hydrazine thrusters (monopropellant or bipropellant with dinitrogen tetroxide), the decreased toxicity makes nitrous oxide an option worth investigating.

Nitrous oxide is said to deflagrate at approximately 600 °C (1,112 °F) at a pressure of 309 psi (21 atmospheres). At 600 psi, for example, the required ignition energy is only 6 joules, whereas N

2O at 130 psi a 2,500-joule ignition energy input is insufficient.

Internal combustion engine

In vehicle racing, nitrous oxide (often referred to as just "nitrous") allows the engine to burn more fuel by providing more oxygen during combustion. The increase in oxygen allows for an increase in the injection of fuel, allowing the engine to produce more engine power. The gas is not flammable at a low pressure/temperature, but it delivers more oxygen than atmospheric air by breaking down at elevated temperatures, about 570 degrees F (~300C). Therefore, it often is mixed with another fuel that is easier to deflagrate. Nitrous oxide is a strong oxidising agent, roughly equivalent to hydrogen peroxide, and much stronger than oxygen gas.

Nitrous oxide is stored as a compressed liquid; the evaporation and expansion of liquid nitrous oxide in the intake manifold causes a large drop in intake charge temperature, resulting in a denser charge, further allowing more air/fuel mixture to enter the cylinder. Sometimes nitrous oxide is injected into (or prior to) the intake manifold, whereas other systems directly inject, right before the cylinder (direct port injection) to increase power.

The technique was used during World War II by Luftwaffe aircraft with the GM-1 system to boost the power output of aircraft engines. Originally meant to provide the Luftwaffe standard aircraft with superior high-altitude performance, technological considerations limited its use to extremely high altitudes. Accordingly, it was only used by specialised planes such as high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, high-speed bombers and high-altitude interceptor aircraft. It sometimes could be found on Luftwaffe aircraft also fitted with another engine-boost system, MW 50, a form of water injection for aviation engines that used methanol for its boost capabilities.

One of the major problems of using nitrous oxide in a reciprocating engine is that it can produce enough power to damage or destroy the engine. Very large power increases are possible, and if the mechanical structure of the engine is not properly reinforced, the engine may be severely damaged, or destroyed, during this kind of operation. It is very important with nitrous oxide augmentation of petrol engines to maintain proper operating temperatures and fuel levels to prevent "pre-ignition", or "detonation" (sometimes referred to as "knock"). Most problems that are associated with nitrous oxide do not come from mechanical failure due to the power increases. Since nitrous oxide allows a much denser charge into the cylinder, it dramatically increases cylinder pressures. The increased pressure and temperature can cause problems such as melting the piston or valves. It also may crack or warp the piston or head and cause pre-ignition due to uneven heating.

Automotive-grade liquid nitrous oxide differs slightly from medical-grade nitrous oxide. A small amount of sulfur dioxide (SO

2) is added to prevent substance abuse.

Aerosol propellant

2O whipped-cream chargers

The gas is approved for use as a food additive (E number: E942), specifically as an aerosol spray propellant. Its most common uses in this context are in aerosol whipped cream canisters and cooking sprays.

The gas is extremely soluble in fatty compounds. In aerosol whipped cream, it is dissolved in the fatty cream until it leaves the can, when it becomes gaseous and thus creates foam. Used in this way, it produces whipped cream which is four times the volume of the liquid, whereas whipping air into cream only produces twice the volume. If air were used as a propellant, oxygen would accelerate rancidification of the butterfat, but nitrous oxide inhibits such degradation. Carbon dioxide cannot be used for whipped cream because it is acidic in water, which would curdle the cream and give it a seltzer-like "sparkling" sensation.

The whipped cream produced with nitrous oxide is unstable, and will return to a more liquid state within half an hour to one hour. Thus, the method is not suitable for decorating food that will not be served immediately.

During December 2016, some manufacturers reported a shortage of aerosol whipped creams in the United States due to an explosion at the Air Liquide nitrous oxide facility in Florida in late August. With a major facility offline, the disruption caused a shortage resulting in the company diverting the supply of nitrous oxide to medical clients rather than to food manufacturing. The shortage came during the Christmas and holiday season when canned whipped cream use is normally at its highest.

Similarly, cooking spray, which is made from various types of oils combined with lecithin (an emulsifier), may use nitrous oxide as a propellant. Other propellants used in cooking spray include food-grade alcohol and propane.

Medicine

2O tanks used in dentistry

Nitrous oxide has been used in dentistry and surgery, as an anaesthetic and analgesic, since 1844. In the early days, the gas was administered through simple inhalers consisting of a breathing bag made of rubber cloth. Today, the gas is administered in hospitals by means of an automated relative analgesia machine, with an anaesthetic vaporiser and a medical ventilator, that delivers a precisely dosed and breath-actuated flow of nitrous oxide mixed with oxygen in a 2:1 ratio.

Nitrous oxide is a weak general anaesthetic, and so is generally not used alone in general anaesthesia, but used as a carrier gas (mixed with oxygen) for more powerful general anaesthetic drugs such as sevoflurane or desflurane. It has a minimum alveolar concentration of 105% and a blood/gas partition coefficient of 0.46. The use of nitrous oxide in anaesthesia, however, can increase the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Dentists use a simpler machine which only delivers an N

2O/O

2

mixture for the patient to inhale while conscious. The patient is kept

conscious throughout the procedure, and retains adequate mental

faculties to respond to questions and instructions from the dentist.

Inhalation of nitrous oxide is used frequently to relieve pain associated with childbirth, trauma, oral surgery and acute coronary syndrome (includes heart attacks). Its use during labour has been shown to be a safe and effective aid for birthing women. Its use for acute coronary syndrome is of unknown benefit.

In Britain and Canada, Entonox and Nitronox are used commonly by ambulance crews (including unregistered practitioners) as rapid and highly effective analgesic gas.

Fifty percent nitrous oxide can be considered for use by trained non-professional first aid responders in prehospital settings, given the relative ease and safety of administering 50% nitrous oxide as an analgesic. The rapid reversibility of its effect would also prevent it from precluding diagnosis.

Recreational use

Recreational inhalation of nitrous oxide, with the purpose of causing euphoria and/or slight hallucinations, began as a phenomenon for the British upper class in 1799, known as "laughing gas parties".

Starting in the nineteenth century, widespread availability of the gas for medical and culinary purposes allowed the recreational use to expand greatly throughout the world. In the United Kingdom, as of 2014, nitrous oxide was estimated to be used by almost half a million young people at nightspots, festivals and parties.

Widespread recreational use of the drug throughout the UK was featured in the 2017 Vice documentary Inside The Laughing Gas Black Market, in which journalist Matt Shea met with dealers of the drug who stole it from hospitals.

A significant issue cited in London's press is the effect of nitrous oxide canister littering, which is highly visible and causes significant complaint from communities.

Recreational users often misperceive nitrous oxide as a route to a "safe high", and are unaware of its potential for causing neurological damage. In Australia, recreation use became a public health concern following a rise in reported cases of neurotoxicity and a rise in emergency room admissions, and in (the state of) South Australia legislation was passed in 2020 to restrict canister sales.

Safety

Nitrous oxide is a significant occupational hazard

for surgeons, dentists and nurses. Because nitrous oxide is minimally

metabolised in humans (with a rate of 0.004%), it retains its potency

when exhaled into the room by the patient, and can pose an intoxicating

and prolonged exposure hazard to the clinic staff if the room is poorly

ventilated. Where nitrous oxide is administered, a continuous-flow

fresh-air ventilation system or N

2O scavenger system is used to prevent a waste-gas buildup.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends that workers' exposure to nitrous oxide should be controlled during the administration of anaesthetic gas in medical, dental and veterinary operators. It set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 25 ppm (46 mg/m3) to escaped anaesthetic.

Mental and manual impairment

Exposure to nitrous oxide causes short-term decreases in mental performance, audiovisual ability and manual dexterity. These effects coupled with the induced spatial and temporal disorientation could result in physical harm to the user from environmental hazards.

Neurotoxicity and neuroprotection

Nitrous oxide is neurotoxic and long-term or habitual use can cause severe neurological damage.

Like other NMDA receptor antagonists, it has been suggested that N

2O produces neurotoxicity in the form of Olney's lesions in rodents upon prolonged (several hour) exposure. New research has arisen suggesting that Olney's lesions do not occur in humans, however, and similar drugs such as ketamine are now believed not to be acutely neurotoxic. It has been argued that, because N

2O is rapidly expelled from the body under normal circumstances, it is less likely to be neurotoxic than other NMDAR antagonists.

Indeed, in rodents, short-term exposure results in only mild injury

that is rapidly reversible, and neuronal death occurs only after

constant and sustained exposure. Nitrous oxide also may cause neurotoxicity after extended exposure because of hypoxia. This is especially true of non-medical formulations such as whipped-cream chargers (also known as "whippets" or "nangs"), which never contain oxygen, since oxygen makes cream rancid.

In heavy (≥400 g or ≥200 L of N2O gas in one session) or frequent (regular, e.g. daily or weekly) users reported to poison control centers, signs of peripheral neuropathy have been noted: the presence of ataxia (gait abnormalities) or paresthesia (perception of abnormal sensations, e.g. tingling, numbness, prickling, mostly in the extremities). These are considered an early sign of neurological damage and indicates chronic toxicity.

Nitrous oxide at 75% by volume reduces ischemia-induced neuronal death induced by occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rodents, and decreases NMDA-induced Ca2+ influx in neuronal cell cultures, a critical event involved in excitotoxicity.

DNA damage

Occupational exposure to ambient nitrous oxide has been associated with DNA damage, due to interruptions in DNA synthesis. This correlation is dose-dependent and does not appear to extend to casual recreational use; however, further research is needed to confirm the duration and quantity of exposure needed to cause damage.

Oxygen deprivation

If pure nitrous oxide is inhaled without oxygen mixed in, this can eventually lead to oxygen deprivation resulting in loss of blood pressure, fainting and even heart attacks. This can occur if the user inhales large quantities continuously, as with a strap-on mask connected to a gas canister. It can also happen if the user engages in excessive breath-holding or uses any other inhalation system that cuts off a supply of fresh air. A further risk is that symptoms of frostbite can occur on the lips, larynx and bronchi if the gas is inhaled directly from the gas container. Therefore, nitrous oxide is often inhaled from condoms or balloons.

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Long-term exposure to nitrous oxide may cause vitamin B12 deficiency. This can cause serious neurotoxicity if the user has preexisting vitamin B12 deficiency. It inactivates the cobalamin form of vitamin B12 by oxidation. Symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, including sensory neuropathy, myelopathy and encephalopathy, may occur within days or weeks of exposure to nitrous oxide anaesthesia in people with subclinical vitamin B12 deficiency.

Symptoms are treated with high doses of vitamin B12, but recovery can be slow and incomplete.

People with normal vitamin B12 levels have stores to make the effects of nitrous oxide insignificant, unless exposure is repeated and prolonged (nitrous oxide abuse). Vitamin B12 levels should be checked in people with risk factors for vitamin B12 deficiency prior to using nitrous oxide anaesthesia.

Prenatal development

Several experimental studies in rats indicate that chronic exposure of pregnant females to nitrous oxide may have adverse effects on the developing fetus.

Chemical/physical risks

At room temperature (20 °C [68 °F]) the saturated vapour pressure is 50.525 bar, rising up to 72.45 bar at 36.4 °C (97.5 °F)—the critical temperature. The pressure curve is thus unusually sensitive to temperature.

As with many strong oxidisers, contamination of parts with fuels have been implicated in rocketry accidents, where small quantities of nitrous/fuel mixtures explode due to "water hammer"-like effects (sometimes called "dieseling"—heating due to adiabatic compression of gases can reach decomposition temperatures). Some common building materials such as stainless steel and aluminium can act as fuels with strong oxidisers such as nitrous oxide, as can contaminants that may ignite due to adiabatic compression.

There also have been incidents where nitrous oxide decomposition in plumbing has led to the explosion of large tanks.

Mechanism of action

The pharmacological mechanism of action of N

2O in medicine is not fully known. However, it has been shown to directly modulate a broad range of ligand-gated ion channels, and this likely plays a major role in many of its effects. It moderately blocks NMDAR and β2-subunit-containing nACh channels, weakly inhibits AMPA, kainate, GABAC and 5-HT3 receptors, and slightly potentiates GABAA and glycine receptors. It also has been shown to activate two-pore-domain K+

channels. While N

2O affects quite a few ion channels, its anaesthetic, hallucinogenic and euphoriant effects are likely caused predominantly, or fully, via inhibition of NMDA receptor-mediated currents. In addition to its effects on ion channels, N

2O may act to imitate nitric oxide (NO) in the central nervous system, and this may be related to its analgesic and anxiolytic properties. Nitrous oxide is 30 to 40 times more soluble than nitrogen.

The effects of inhaling sub-anaesthetic doses of nitrous oxide have been known to vary, based on several factors, including settings and individual differences; however, from his discussion, Jay (2008) suggests that it has been reliably known to induce the following states and sensations:

- Intoxication

- Euphoria/dysphoria

- Spatial disorientation

- Temporal disorientation

- Reduced pain sensitivity

A minority of users also will present with uncontrolled vocalisations and muscular spasms. These effects generally disappear minutes after removal of the nitrous oxide source.

Anxiolytic effect

In behavioural tests of anxiety, a low dose of N

2O is an effective anxiolytic, and this anti-anxiety effect is associated with enhanced activity of GABAA receptors, as it is partially reversed by benzodiazepine receptor antagonists. Mirroring this, animals that have developed tolerance to the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines are partially tolerant to N

2O. Indeed, in humans given 30% N

2O, benzodiazepine receptor antagonists reduced the subjective reports of feeling "high", but did not alter psychomotor performance, in human clinical studies.

Analgesic effect

The analgesic effects of N

2O are linked to the interaction between the endogenous opioid system and the descending noradrenergic

system. When animals are given morphine chronically, they develop

tolerance to its pain-killing effects, and this also renders the animals

tolerant to the analgesic effects of N

2O. Administration of antibodies that bind and block the activity of some endogenous opioids (not β-endorphin) also block the antinociceptive effects of N

2O. Drugs that inhibit the breakdown of endogenous opioids also potentiate the antinociceptive effects of N

2O.

Several experiments have shown that opioid receptor antagonists applied

directly to the brain block the antinociceptive effects of N

2O, but these drugs have no effect when injected into the spinal cord.

Apart from an indirect action, nitrous oxide, like morphine also interacts directly with the endogenous opioid system by binding at opioid receptor binding sites.

Conversely, α2-adrenoceptor antagonists block the pain-reducing effects of N

2O when given directly to the spinal cord, but not when applied directly to the brain. Indeed, α2B-adrenoceptor knockout mice or animals depleted in norepinephrine are nearly completely resistant to the antinociceptive effects of N

2O.[81] Apparently N

2O-induced release of endogenous opioids causes disinhibition of brainstem noradrenergic neurons, which release norepinephrine into the spinal cord and inhibit pain signalling. Exactly how N

2O causes the release of endogenous opioid peptides remains uncertain.

Properties and reactions

Nitrous oxide is a colourless, non-toxic gas with a faint, sweet odour.

Nitrous oxide supports combustion by releasing the dipolar bonded oxygen radical, and can thus relight a glowing splint.

N

2O

is inert at room temperature and has few reactions. At elevated

temperatures, its reactivity increases. For example, nitrous oxide

reacts with NaNH

2 at 460 K (187 °C) to give NaN

3:

- 2 NaNH

2 + N

2O → NaN

3 + NaOH + NH

3

The above reaction is the route adopted by the commercial chemical industry to produce azide salts, which are used as detonators.

History

The gas was first synthesised in 1772 by English natural philosopher and chemist Joseph Priestley who called it dephlogisticated nitrous air (see phlogiston theory) or inflammable nitrous air. Priestley published his discovery in the book Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (1775), where he described how to produce the preparation of "nitrous air diminished", by heating iron filings dampened with nitric acid.

Early use

The first important use of nitrous oxide was made possible by Thomas Beddoes and James Watt, who worked together to publish the book Considerations on the Medical Use and on the Production of Factitious Airs (1794). This book was important for two reasons. First, James Watt had invented a novel machine to produce "factitious airs" (including nitrous oxide) and a novel "breathing apparatus" to inhale the gas. Second, the book also presented the new medical theories by Thomas Beddoes, that tuberculosis and other lung diseases could be treated by inhalation of "Factitious Airs".

The machine to produce "Factitious Airs" had three parts: a furnace to burn the needed material, a vessel with water where the produced gas passed through in a spiral pipe (for impurities to be "washed off"), and finally the gas cylinder with a gasometer where the gas produced, "air", could be tapped into portable air bags (made of airtight oily silk). The breathing apparatus consisted of one of the portable air bags connected with a tube to a mouthpiece. With this new equipment being engineered and produced by 1794, the way was paved for clinical trials, which began in 1798 when Thomas Beddoes established the "Pneumatic Institution for Relieving Diseases by Medical Airs" in Hotwells (Bristol). In the basement of the building, a large-scale machine was producing the gases under the supervision of a young Humphry Davy, who was encouraged to experiment with new gases for patients to inhale. The first important work of Davy was examination of the nitrous oxide, and the publication of his results in the book: Researches, Chemical and Philosophical (1800). In that publication, Davy notes the analgesic effect of nitrous oxide at page 465 and its potential to be used for surgical operations at page 556. Davy coined the name "laughing gas" for nitrous oxide.

Despite Davy's discovery that inhalation of nitrous oxide could relieve a conscious person from pain, another 44 years elapsed before doctors attempted to use it for anaesthesia. The use of nitrous oxide as a recreational drug at "laughing gas parties", primarily arranged for the British upper class, became an immediate success beginning in 1799. While the effects of the gas generally make the user appear stuporous, dreamy and sedated, some people also "get the giggles" in a state of euphoria, and frequently erupt in laughter.

One of the earliest commercial producers in the U.S. was George Poe, cousin of the poet Edgar Allan Poe, who also was the first to liquefy the gas.

Anaesthetic use

The first time nitrous oxide was used as an anaesthetic drug in the treatment of a patient was when dentist Horace Wells, with assistance by Gardner Quincy Colton and John Mankey Riggs, demonstrated insensitivity to pain from a dental extraction on 11 December 1844. In the following weeks, Wells treated the first 12 to 15 patients with nitrous oxide in Hartford, Connecticut, and, according to his own record, only failed in two cases. In spite of these convincing results having been reported by Wells to the medical society in Boston in December 1844, this new method was not immediately adopted by other dentists. The reason for this was most likely that Wells, in January 1845 at his first public demonstration to the medical faculty in Boston, had been partly unsuccessful, leaving his colleagues doubtful regarding its efficacy and safety. The method did not come into general use until 1863, when Gardner Quincy Colton successfully started to use it in all his "Colton Dental Association" clinics, that he had just established in New Haven and New York City. Over the following three years, Colton and his associates successfully administered nitrous oxide to more than 25,000 patients. Today, nitrous oxide is used in dentistry as an anxiolytic, as an adjunct to local anaesthetic.

Nitrous oxide was not found to be a strong enough anaesthetic for use in major surgery in hospital settings, however. Instead, diethyl ether, being a stronger and more potent anaesthetic, was demonstrated and accepted for use in October 1846, along with chloroform in 1847. When Joseph Thomas Clover invented the "gas-ether inhaler" in 1876, however, it became a common practice at hospitals to initiate all anaesthetic treatments with a mild flow of nitrous oxide, and then gradually increase the anaesthesia with the stronger ether or chloroform. Clover's gas-ether inhaler was designed to supply the patient with nitrous oxide and ether at the same time, with the exact mixture being controlled by the operator of the device. It remained in use by many hospitals until the 1930s. Although hospitals today use a more advanced anaesthetic machine, these machines still use the same principle launched with Clover's gas-ether inhaler, to initiate the anaesthesia with nitrous oxide, before the administration of a more powerful anaesthetic.

As a patent medicine

Colton's popularisation of nitrous oxide led to its adoption by a number of less than reputable quacksalvers, who touted it as a cure for consumption, scrofula, catarrh and other diseases of the blood, throat and lungs. Nitrous oxide treatment was administered and licensed as a patent medicine by the likes of C. L. Blood and Jerome Harris in Boston and Charles E. Barney of Chicago.

Production

Reviewing various methods of producing nitrous oxide is published.

Industrial methods

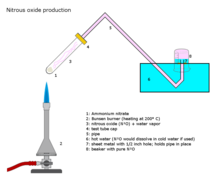

Nitrous oxide is prepared on an industrial scale by careful heating of ammonium nitrate at about 250 °C, which decomposes into nitrous oxide and water vapour.

- NH

4NO

3 → 2 H

2O + N

2O

The addition of various phosphate salts favours formation of a purer gas at slightly lower temperatures. This reaction may be difficult to control, resulting in detonation.

Laboratory methods

The decomposition of ammonium nitrate is also a common laboratory method for preparing the gas. Equivalently, it can be obtained by heating a mixture of sodium nitrate and ammonium sulfate:

- 2 NaNO

3 + (NH

4)2SO

4 → Na

2SO

4 + 2 N

2O + 4 H

2O

Another method involves the reaction of urea, nitric acid and sulfuric acid:

- 2 (NH2)2CO + 2 HNO

3 + H

2SO

4 → 2 N

2O + 2 CO

2 + (NH4)2SO4 + 2 H

2O

Direct oxidation of ammonia with a manganese dioxide-bismuth oxide catalyst has been reported: cf. Ostwald process.

- 2 NH

3 + 2 O

2 → N

2O + 3 H

2O

Hydroxylammonium chloride reacts with sodium nitrite to give nitrous oxide. If the nitrite is added to the hydroxylamine solution, the only remaining by-product is salt water. If the hydroxylamine solution is added to the nitrite solution (nitrite is in excess), however, then toxic higher oxides of nitrogen also are formed:

- NH

3OHCl + NaNO

2 → N

2O + NaCl + 2 H

2O

Treating HNO

3 with SnCl

2 and HCl also has been demonstrated:

- 2 HNO

3 + 8 HCl + 4 SnCl

2 → 5 H

2O + 4 SnCl

4 + N

2O

Hyponitrous acid decomposes to N2O and water with a half-life of 16 days at 25 °C at pH 1–3.

- H2N2O2→ H2O + N2O

Atmospheric occurrence

Nitrous oxide is a minor component of Earth's atmosphere and is an active part of the planetary nitrogen cycle. Based on analysis of air samples gathered from sites around the world, its concentration surpassed 330 ppb in 2017. The growth rate of about 1 ppb per year has also accelerated during recent decades. Nitrous oxide's atmospheric abundance has grown more than 20% from a base level of about 270 ppb in year 1750.

Important atmospheric properties of N

2O are summarized in the following table:

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Ozone depletion potential (ODP) | 0.17 (CCl3F = 1) |

| Global warming potential (GWP: 100-year) | 265 (CO2 = 1) |

| Atmospheric lifetime | 121 years |

In October 2020 scientists published a comprehensive quantification of global N

2O

sources and sinks. They report that human-induced emissions increased

by 30% over the past four decades and are the main cause of the increase

in atmospheric concentration. The recent growth has exceeded some of

the highest projected emission scenarios.

Emissions by source

As of 2010, it was estimated that about 29.5 million tonnes of N

2O

(containing 18.8 million tonnes of nitrogen) were entering the

atmosphere each year; of which 64% were natural, and 36% due to human

activity.

Most of the N

2O emitted into the atmosphere, from natural and anthropogenic sources, is produced by microorganisms such as denitrifying bacteria and fungi in soils and oceans.

Soils under natural vegetation are an important source of nitrous

oxide, accounting for 60% of all naturally produced emissions. Other

natural sources include the oceans (35%) and atmospheric chemical

reactions (5%).

A 2019 study showed that emissions from thawing permafrost are 12 times higher than previously assumed.

The main components of anthropogenic emissions are fertilised agricultural soils and livestock manure (42%), runoff and leaching of fertilisers (25%), biomass burning (10%), fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes (10%), biological degradation of other nitrogen-containing atmospheric emissions (9%) and human sewage (5%). Agriculture enhances nitrous oxide production through soil cultivation, the use of nitrogen fertilisers and animal waste handling. These activities stimulate naturally occurring bacteria to produce more nitrous oxide. Nitrous oxide emissions from soil can be challenging to measure as they vary markedly over time and space, and the majority of a year's emissions may occur when conditions are favorable during "hot moments" and/or at favorable locations known as "hotspots".

Among industrial emissions, the production of nitric acid and adipic acid are the largest sources of nitrous oxide emissions. The adipic acid emissions specifically arise from the degradation of the nitrolic acid intermediate derived from nitration of cyclohexanone.

Biological processes

Natural processes that generate nitrous oxide may be classified as nitrification and denitrification. Specifically, they include:

- aerobic autotrophic nitrification, the stepwise oxidation of ammonia (NH

3) to nitrite (NO−

2) and to nitrate (NO−

3) - anaerobic heterotrophic denitrification, the stepwise reduction of NO−

3 to NO−

2, nitric oxide (NO), N

2O and ultimately N

2, where facultative anaerobe bacteria use NO−

3 as an electron acceptor in the respiration of organic material in the condition of insufficient oxygen (O

2) - nitrifier denitrification, which is carried out by autotrophic NH

3-oxidising bacteria and the pathway whereby ammonia (NH

3) is oxidised to nitrite (NO−

2), followed by the reduction of NO−

2 to nitric oxide (NO), N

2O and molecular nitrogen (N

2) - heterotrophic nitrification

- aerobic denitrification by the same heterotrophic nitrifiers

- fungal denitrification

- non-biological chemodenitrification

These processes are affected by soil chemical and physical properties such as the availability of mineral nitrogen and organic matter, acidity and soil type, as well as climate-related factors such as soil temperature and water content.

The emission of the gas to the atmosphere is limited greatly by its consumption inside the cells, by a process catalysed by the enzyme nitrous oxide reductase.

Environmental impact

Greenhouse effect

Nitrous oxide has significant global warming potential as a greenhouse gas.

On a per-molecule basis, considered over a 100-year period, nitrous

oxide has 265 times the atmospheric heat-trapping ability of carbon dioxide (CO

2). However, because of its low concentration (less than 1/1,000 of that of CO

2), its contribution to the greenhouse effect is less than one third that of carbon dioxide, and also less than water vapour and methane. On the other hand, since 38% or more of the N

2O entering the atmosphere is the result of human activity, control of nitrous oxide is considered part of efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

A 2008 study by Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen suggests that the amount of nitrous oxide release attributable to agricultural nitrate fertilisers has been seriously underestimated, most of which presumably, would come under soil and oceanic release in the Environmental Protection Agency data. Nitrous oxide is released into the atmosphere through agriculture, when farmers add nitrogen-based fertilizers onto the fields, and through the breakdown of animal manure. Approximately 79 percent of all nitrous oxide released in the United States came from nitrogen fertilization. Reduction of emissions can be a hot topic in the politics of climate change.

Nitrous oxide is also released as a by-product of burning fossil fuel, though the amount released depends on which fuel was used. It is also emitted through the manufacture of nitric acid, which is used in the synthesis of nitrogen fertilizers. The production of adipic acid, a precursor to nylon and other synthetic clothing fibres, also releases nitrous oxide. The total amount of nitrous oxide released that is of human origins is about 40 percent.

Ozone layer depletion

Nitrous oxide has also been implicated in thinning the ozone layer. A 2009 study suggested that N

2O

emission was the single most important ozone-depleting emission and it

was expected to remain the largest throughout the 21st century.

Legality

In the United States, possession of nitrous oxide is legal under federal law and is not subject to DEA purview. It is, however, regulated by the Food and Drug Administration under the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act; prosecution is possible under its "misbranding" clauses, prohibiting the sale or distribution of nitrous oxide for the purpose of human consumption. Many states have laws regulating the possession, sale and distribution of nitrous oxide. Such laws usually ban distribution to minors or limit the amount of nitrous oxide that may be sold without special license. For example, in the state of California, possession for recreational use is prohibited and qualifies as a misdemeanor.

In August 2015, the Council of the London Borough of Lambeth (UK) banned the use of the drug for recreational purposes, making offenders liable to an on-the-spot fine of up to £1,000.

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Health has warned that nitrous oxide is a prescription medicine, and its sale or possession without a prescription is an offense under the Medicines Act. This statement would seemingly prohibit all non-medicinal uses of nitrous oxide, although it is implied that only recreational use will be targeted legally.

In India, transfer of nitrous oxide from bulk cylinders to smaller, more transportable E-type, 1,590-litre-capacity tanks is legal when the intended use of the gas is for medical anaesthesia.