Major anarchist thinkers (except Proudhon), past and present, have generally supported women's equality. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, viewing sexual freedom as an expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights. In New York's Greenwich Village, "bohemian" feminists and socialists advocated self-realisation and pleasure for both men and women. In Europe and North America, the free love movement combined ideas revived from utopian socialism with anarchism and feminism to attack the "hypocritical" sexual morality of the Victorian era.

Beginnings

The major male anarchist thinkers, with the exception of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, strongly supported women's equality. Mikhail Bakunin, for example, opposed patriarchy and the way the law "subjects [women] to the absolute domination of the man." He argued that "[e]qual rights must belong to men and women" so that women can "become independent and be free to forge their own way of life." Bakunin foresaw "the full sexual freedom of women" and the end of "the authoritarian juridical family". Proudhon, on the other hand, viewed the family as the most basic unit of society and morality, and thought women had the responsibility of fulfilling a traditional role within the family.

In Oscar Wilde's The Soul of Man Under Socialism, he passionately advocates for an egalitarian society where wealth is shared by all, while warning of the dangers of authoritarian socialism that would crush individuality. He later commented, "I think I am rather more than a Socialist. I am something of an Anarchist, I believe." Wilde's left libertarian politics were shared by other figures who actively campaigned for homosexual emancipation in the late 19th century, including John Henry Mackay and Edward Carpenter. "In August 1894, Wilde wrote to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, to tell of “a dangerous adventure.” He had gone out sailing with two lovely boys, Stephen and Alphonso, and they were caught in a storm. “We took five hours in an awful gale to come back! [And we] did not reach pier till eleven o’clock at night, pitch dark all the way, and a fearful sea. . . . All the fishermen were waiting for us.”...Tired, cold, and “wet to the skin,” the three men immediately “flew to the hotel for hot brandy and water.” But there was a problem. The law stood in the way: “As it was past ten o’clock on a Sunday night the proprietor could not sell us any brandy or spirits of any kind! So he had to give it to us. The result was not displeasing, but what laws!”...Wilde finishes the story: “Both Alphonso and Stephen are now anarchists, I need hardly say.”"

Free love and anarchism

United States

An important current within American individualist anarchism was free love. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures. The most important American free love journal was Lucifer the Lightbearer (1883–1907) edited by Moses Harman and Lois Waisbrooker but also there existed Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood's The Word (1872–1890, 1892–1893). Also M. E. Lazarus was an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.

Free Society (1895–1897 as The Firebrand; 1897-1904 as Free Society) was a major anarchist newspaper in the United States at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. The publication staunchly advocated free love and women's rights, and critiqued "Comstockery" -- censorship of sexual information. Deliberately defying "Comstockism" in an act of civil disobedience, The Firebrand published Walt Whitman's "A Woman Waits for Me" in 1897; A. J. Pope, Abe Isaak, and Henry Addis were quickly arrested and charged with publishing obscene information for the Whitman poem and a letter "It Depends on the Women", signed by A.E.K. The A.E.K. letter presented various hypotheticals of women refusing or assenting to sex with their husbands or lovers, and argued that true liberation required education of both sexes and particularly women.

In New York's Greenwich Village, "bohemian" feminists and socialists advocated self-realisation and pleasure for women (and also men) in the here and now, as well as campaigning against the first World War and for other anarchist and socialist causes. They encouraged playing with sexual roles and sexuality, and the openly bisexual radical Edna St. Vincent Millay and the lesbian anarchist Margaret Anderson were prominent among them. The Villagers took their inspiration from the (mostly anarchist) immigrant female workers from the period 1905-1915 and the "New Life Socialism" of Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis and Olive Schreiner. Discussion groups organised by the Villagers were frequented by Emma Goldman, among others. Magnus Hirschfeld noted in 1923 that Goldman "has campaigned boldly and steadfastly for individual rights, and especially for those deprived of their rights. Thus it came about that she was the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public." In fact, prior to Goldman, heterosexual anarchist Robert Reitzel (1849–98) spoke positively of homosexuality from the beginning of the 1890s in his German-language journal "Der arme Teufel" (Detroit).

In Europe and North America, the free love movement combined ideas revived from utopian socialism with anarchism and feminism to attack the "hypocritical" sexual morality of the Victorian era, and the institutions of marriage and the family that were seen to enslave women. Free lovers advocated voluntary sexual unions with no state interference and affirmed the right to sexual pleasure for both women and men, sometimes explicitly supporting the rights of homosexuals and prostitutes. For a few decades, adherence to "free love" became widespread among European and American anarchists, but these views were opposed at the time by the dominant actors of the Left: Marxists and social democrats. Radical feminist and socialist Victoria Woodhull was expelled from the International Workingmen's Association in 1871 for her involvement in the free love and associated movements. Indeed, with Marx's support, the American branch of the organisation was purged of its pacifist, anti-racist and feminist elements, which were accused of putting too much emphasis on issues unrelated to class struggle and were therefore seen to be incompatible with the "scientific socialism" of Marx and Engels.

Europe

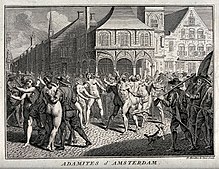

French and Spanish individualist anarchist circles had a strong sense of personal libertarianism and experimentation. Free love contents started to have a strong influence in individualist anarchist circles and from there it expanded to the rest of anarchism also appearing in Spanish individualist anarchist groups.

"In this sense, the theoretical positions and the vital experiences of French individualism are deeply iconoclastic and scandalous, even within libertarian circles. The call of nudist naturism, the strong defence of birth control methods, the idea of "unions of egoists" with the sole justification of sexual practices, that will try to put in practice, not without difficulties, will establish a way of thought and action, and will result in sympathy within some, and a strong rejection within others." Periodicals involved in this movement include L'En-Dehors in France and Iniciales and La Revista Blanca in Spain.

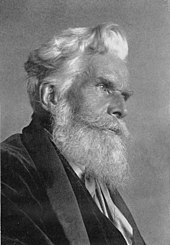

Émile Armand

The main propagandist of free love within European individualist anarchism was Émile Armand. He advocated naturism (see anarcho-naturism) and polyamory and he came up with the concept of la camaraderie amoureuse. He wrote many propagandist articles on this subject such as "De la liberté sexuelle" (1907) where he advocated not only a vague free love but also multiple partners, which he called "plural love". In the individualist anarchist journal L'En-Dehors he and others continued in this way. Armand seized this opportunity to outline his theses supporting revolutionary sexualism and "camaraderie amoureuse" that differed from the traditional views of the partisans of free love in several respects.

Later Armand submitted that from an individualist perspective nothing was reprehensible about making "love", even if one did not have very strong feelings for one's partner. "The camaraderie amoureuse thesis", he explained, "entails a free contract of association (that may be annulled without notice, following prior agreement) reached between anarchist individualists of different genders, adhering to the necessary standards of sexual hygiene, with a view toward protecting the other parties to the contract from certain risks of the amorous experience, such as rejection, rupture, exclusivism, possessiveness, unicity, coquetry, whims, indifference, flirtatiousness, disregard for others, and prostitution." He also published Le Combat contre la jalousie et le sexualisme révolutionnaire (1926), followed over the years by Ce que nous entendons par liberté de l'amour (1928), La Camaraderie amoureuse ou “chiennerie sexuelle” (1930), and, finally, La Révolution sexuelle et la camaraderie amoureuse (1934), a book of nearly 350 pages comprising most of his writings on sexuality.

In a text from 1937, he mentioned among the individualist objectives the practice of forming voluntary associations for purely sexual purposes of heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual nature or of a combination thereof. He also supported the right of individuals to change sex and stated his willingness to rehabilitate forbidden pleasures, non-conformist caresses (he was personally inclined toward voyeurism), as well as sodomy. This led him to allocate more and more space to what he called "the sexual non-conformists", while excluding physical violence. His militancy also included translating texts from people such as Alexandra Kollontai and Wilhelm Reich and establishments of free love associations which tried to put into practice la camaraderie amoureuse through actual sexual experiences.

The prestige in the subject of free love of Armand within anarchist circles was such as to motivate the young Argentinian anarchist América Scarfó to ask Armand in a letter on advice as to how to deal with the relationship she had with notorious Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni. Di Giovanni was still married when they began the relationship. "The letter was published in L'En-Dehors" on 20 January 1929 under the title “An Experience”, together with the reply from E. Armand". Armand replied to Scarfó "“Comrade: My opinion matters little in this matter you send me about what you are doing. Are you or are you not intimately in accord with your personal conception of the anarchist life? If you are, then ignore the comments and insults of others and carry on following your own path. No one has the right to judge your way of conducting yourself, even if it were the case that your friend's wife be hostile to these relations. Every woman united to an anarchist (or vice versa), knows very well that she should not exercise on him, or accept from him, domination of any kind.”"

Errico Malatesta

The treatment of the issue of love by the influential Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta deserves attention. Malatesta says in Love and Anarchy, "Let's eliminate the exploitation of man by man, let's fight the brutal pretention of the male who thinks he owns the female, let's fight religious, social and sexual prejudice, let's expand education and then we will be happy with reason if there are no more evils than love. In any case, the ones with bad luck in love will procur themselves other pleasures, since it will not happen like today, when love and alcohol are the only consolations of the majority of humanity."

Anarcha-feminism

Anarcha-feminism was inspired by late 19th and early 20th century authors and theorists such as anarchist feminists Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and Lucy Parsons. In the Spanish Civil War, an anarcha-feminist group, Mujeres Libres ("Free Women") linked to the Federación Anarquista Ibérica, organized to defend both anarchist and feminist ideas, while Stirnerist Nietzschean feminist Federica Montseny held that the "emancipation of women would lead to a quicker realization of the social revolution" and that "the revolution against sexism would have to come from intellectual and militant 'future-women.' According to this Nietzschean concept of Federica Monteseny's, women could realize through art and literature the need to revise their own roles."

Since the 1860s, anarchism's radical critique of capitalism and the state has been combined with a critique of patriarchy. Anarcha-feminists thus start from the precept that modern society is dominated by men. Authoritarian traits and values—domination, exploitation, aggression, competition. etc.—are integral to hierarchical civilizations and are seen as "masculine." In contrast, non-authoritarian traits and values—cooperation, sharing, compassion, sensitivity—are regarded as "feminine," and devalued. Anarcha-feminists have thus espoused creation of a non-authoritarian, anarchist society. They refer to the creation of a society, based on cooperation, sharing, mutual aid, etc. as the "feminization of society."

Emma Goldman

Although she was hostile to first-wave feminism and its suffragist goals, Emma Goldman advocated passionately for the rights of women, and is today heralded as a founder of anarcha-feminism, which challenges patriarchy as a hierarchy to be resisted alongside state power and class divisions. In 1897 she wrote: "I demand the independence of woman, her right to support herself; to live for herself; to love whomever she pleases, or as many as she pleases. I demand freedom for both sexes, freedom of action, freedom in love and freedom in motherhood."

A nurse by training, Emma Goldman was an early advocate for educating women concerning contraception. Like many contemporary feminists, she saw abortion as a tragic consequence of social conditions, and birth control as a positive alternative. Goldman was also an advocate of free love, and a strong critic of marriage. She saw early feminists as confined in their scope and bounded by social forces of Puritanism and capitalism. She wrote: "We are in need of unhampered growth out of old traditions and habits. The movement for women's emancipation has so far made but the first step in that direction."

Sex education

Goldman in her essay on the Modern School also dealt with the issue of Sex Education. She denounced that "educators also know the evil and sinister results of ignorance in sex matters. Yet, they have neither understanding nor humanity enough to break down the wall which puritanism has built around sex...If in childhood both man and woman were taught a beautiful comradeship, it would neutralize the oversexed condition of both and would help woman's emancipation much more than all the laws upon the statute books and her right to vote."

Mujeres Libres

Mujeres Libres (English: Free Women) was an anarchist women's organization in Spain that aimed to empower working class women. It was founded in 1936 by Lucía Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch y Gascón and had approximately 30,000 members. The organization was based on the idea of a "double struggle" for women's liberation and social revolution and argued that the two objectives were equally important and should be pursued in parallel. In order to gain mutual support, they created networks of women anarchists. Flying day-care centres were set up in efforts to involve more women in union activities.

In revolutionary Spain of the 1930s, many anarchist women were angry with what they viewed as persistent sexism amongst anarchist men and their marginalized status within a movement that ostensibly sought to abolish domination and hierarchy. They saw women's problems as inseparable from the social problems of the day; while they shared their compañero's desire for social revolution they also pushed for recognition of women's abilities and organized in their communities to achieve that goal. Citing the anarchist assertion that the means of revolutionary struggle must model the desired organization of revolutionary society, they rejected mainstream Spanish anarchism's assertion that women's equality would follow automatically from the social revolution. To prepare women for leadership roles in the anarchist movement, they organized schools, women-only social groups and a women-only newspaper so that women could gain self-esteem and confidence in their abilities and network with one another to develop their political consciousness.

Lucía Sánchez Saornil was a main founder of the Spanish anarcha-feminist federation Mujeres Libres who was open about her lesbianism. At a young age she began writing poetry and associated herself with the emerging Ultraist literary movement. By 1919, she had been published in a variety of journals, including Los Quijotes, Tableros, Plural, Manantial and La Gaceta Literaria. Working under a male pen name, she was able to explore lesbian themes at a time when homosexuality was criminalized and subject to censorship and punishment. Dissatisfied with the chauvinistic prejudices of fellow republicans, Lucía Sánchez Saornil joined with two compañeras, Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch y Gascón, to form Mujeres Libres in 1936. Mujeres Libres was an autonomous anarchist organization for women committed to a "double struggle" of women's liberation and social revolution. Lucía and other "Free Women" rejected the dominant view that gender equality would emerge naturally from a classless society. As the Spanish Civil War exploded, Mujeres Libres quickly grew to 30,000 members, organizing women's social spaces, schools, newspapers and daycare programs.

Queer anarchism

Anarchism's foregrounding of individual freedoms made for a natural marriage with homosexuality in the eyes of many, both inside and outside of the Anarchist movement. Emil Szittya, in Das Kuriositäten-Kabinett (1923), wrote about homosexuality that "very many anarchists have this tendency. Thus I found in Paris a Hungarian anarchist, Alexander Sommi, who founded a homosexual anarchist group on the basis of this idea.” His view is confirmed by Magnus Hirschfeld in his 1914 book Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes: “In the ranks of a relatively small party, the anarchist, it seemed to me as if proportionately more homosexuals and effeminates are found than in others.” Italian anarchist Luigi Bertoni (whom Szittya also believed to be homosexual) observed that “Anarchists demand freedom in everything, thus also in sexuality. Homosexuality leads to a healthy sense of egoism, for which every anarchist should strive.”

Anarcho-syndicalist writer Ulrich Linse wrote about "a sharply outlined figure of the Berlin individualist anarchist cultural scene around 1900", the "precocious Johannes Holzmann" (known as Senna Hoy): "an adherent of free love, [Hoy] celebrated homosexuality as a ‘champion of culture’ and engaged in the struggle against Paragraph 175.” The young Hoy (born 1882) published these views in his weekly magazine, ("Kampf") from 1904 which reached a circulation of 10,000 the following year. German anarchist psychotherapist Otto Gross also wrote extensively about same-sex sexuality in both men and women and argued against its discrimination. In the 1920s and 1930s, French individualist anarchist publisher Émile Armand campaigned for acceptance of free love, including homosexuality, in his journal L'En-Dehors.

From 1906, the writings and theories of John Henry Mackay had a significant influence on Adolf Brand's organisation Gemeinschaft der Eigenen. The individualist anarchist Adolf Brand was originally a member of Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanitarian committee, but formed a break-away group. Brand and his colleagues, known as the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen, were heavily influenced by homosexual anarchist John Henry Mackay. They were opposed to Hirschfeld's medical characterisation of homosexuality as the domain of an "intermediate sex". and disdained the Jewish Hirschfeld. Ewald Tschek, another homosexual anarchist writer of the era, regularly contributed to Adolf Brand's journal Der Eigene, and wrote in 1925 that Hirschfeld’s Scientific Humanitarian Committee was a danger to the German people, caricaturing Hirschfeld as "Dr. Feldhirsch".

Der Eigene was the first Gay journal in the world, published from 1896 to 1932 by Adolf Brand in Berlin. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself. Other contributors included Benedict Friedlaender, Hanns Heinz Ewers, Erich Mühsam, Kurt Hiller, Ernst Burchard, John Henry Mackay, Theodor Lessing, Klaus Mann, and Thomas Mann, as well as artists Wilhelm von Gloeden, Fidus, and Sascha Schneider. The journal may have had an average of around 1500 subscribers per issue during its run, but the exact numbers are uncertain. After the rise to power by the Nazis, Brand became a victim of persecution and had his journal closed.

Anarchist homophobia

Despite these supportive stances, the anarchist movement of the time certainly wasn't free of homophobia: an editorial in an influential Spanish anarchist journal from 1935 argued that an Anarchist shouldn't even associate with homosexuals, let alone be one: "If you are an anarchist, that means that you are more morally upright and physically strong than the average man. And he who likes inverts is no real man, and is therefore no real anarchist."

Daniel Guérin was a leading figure in the French Left from the 1930s until his death in 1988. After coming out in 1965, he spoke about the extreme hostility toward homosexuality that permeated the Left throughout much of the 20th century. "Not so many years ago, to declare oneself a revolutionary and to confess to being homosexual were incompatible," Guérin wrote in 1975. In 1954, Guérin was widely attacked for his study of the Kinsey Reports in which he also detailed the oppression of homosexuals in France: "The harshest [criticisms] came from Marxists, who tend seriously to underestimate the form of oppression which is antisexual terrorism. I expected it, of course, and I knew that in publishing my book I was running the risk of being attacked by those to whom I feel closest on a political level." Later sexual anarchists continued in that vein. In 1993, the "Boston Anarchist Drinking Brigade" criticized "anti-porn activists who are frankly censorious."

Émile Armand advocated naturism (see anarcho-naturism) and polyamory. He also called for forming voluntary associations for purely sexual purposes of heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual nature or of a combination thereof. Anarcha-feminism was inspired by late 19th and early 20th century authors and theorists such as anarchist feminists Emma Goldman, Voltairine de Cleyre and Lucy Parsons. Emil Szittya, in Das Kuriositäten-Kabinett (1923), wrote about homosexuality that "very many anarchists have this tendency... Homosexuality leads to a healthy sense of egoism, for which every anarchist should strive.”

Later 20th century and contemporary times

The writings of the French bisexual anarchist Daniel Guérin offer an insight into the tension sexual minorities among the Left have often felt. He was a leading figure in the French Left from the 1930s until his death in 1988. After coming out in 1965, he spoke about the extreme hostility toward homosexuality that permeated the Left throughout much of the 20th century. "Not so many years ago, to declare oneself a revolutionary and to confess to being homosexual were incompatible," Guérin wrote in 1975. In 1954, Guérin was widely attacked for his study of the Kinsey Reports in which he also detailed the oppression of homosexuals in France. "The harshest [criticisms] came from Marxists, who tend seriously to underestimate the form of oppression which is antisexual terrorism. I expected it, of course, and I knew that in publishing my book I was running the risk of being attacked by those to whom I feel closest on a political level." After coming out publicly in 1965, Guérin was abandoned by the Left, and his papers on sexual liberation were censored or refused publication in left-wing journals. From the 1950s, Guérin moved away from Marxism-Leninism and toward a synthesis of anarchism and communism which allowed for individualism while rejecting capitalism. Guérin was involved in the uprising of May 1968, and was a part of the French Gay Liberation movement that emerged after the events. Decades later, Frédéric Martel described Guérin as the "grandfather of the French homosexual movement."

The British anarcho-pacifist Alex Comfort gained notoriety for writing the bestseller sex manual The Joy of Sex (1972) in the context of the sexual revolution. Queer Fist appeared in New York City and identifies itself as "an anti-assimilationist, anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian street action group, came together to provide direct action and a radical queer and trans-identified voice at the Republican National Convention (RNC) protests." Anarcha -feminism continues in new forms such as the Bolivian collective Mujeres Creando or the Spanish anarcha-feminist squat Eskalera Karakola. Contemporary anarcha-feminist writers/theorists include L. Susan Brown and the eco-feminist Starhawk.

The issue of free love has a dedicated treatment in the work of French anarcho-hedonist philosopher Michel Onfray in such works as Théorie du corps amoureux : pour une érotique solaire (2000) and L'invention du plaisir : fragments cyréaniques (2002).

Anarchists in high heels

"Anarchists in high heels" are anarchists (or sometimes radicals or libertarians) who work in the sex industry. The term can be found being used in XXX: A Womanʼs Right to Pornography by Wendy McElroy where porn actress, Veronica Hart, makes this comment upon hearing the word ‘feminist’:

“I donʼt need Andrea Dworkin to tell me what to think or how to behave.” [...] “And I donʼt appreciate being called psychologically damaged! I have friends in the business who call themselves ‘Anarchists in High Heels.’ Theyʼd love to have a word with her.”