| Suicide | |

|---|---|

| |

| Le Suicidé by Édouard Manet | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology, clinical social work |

| Usual onset | 15–30 and 70+ years old |

| Risk factors | Depression, bipolar disorder, autism, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders, alcoholism, substance abuse |

| Prevention | Limiting access to methods of suicide, treating mental disorders and substance misuse, careful media reporting about suicide, improving social and economic conditions |

| Frequency | 12 per 100,000 per year |

| Deaths | 793,000 / 1.5% of deaths (2016) |

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and substance abuse (including alcoholism and the use of and withdrawal from benzodiazepines) are risk factors. Some suicides are impulsive acts due to stress (such as from financial or academic difficulties), relationship problems (such as breakups or divorces), or harassment and bullying. Those who have previously attempted suicide are at a higher risk for future attempts. Effective suicide prevention efforts include limiting access to methods of suicide such as firearms, drugs, and poisons; treating mental disorders and substance abuse; careful media reporting about suicide; and improving economic conditions. Although crisis hotlines are common resources, their effectiveness has not been well studied.

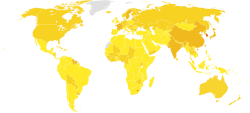

The most commonly adopted method of suicide varies from country to country and is partly related to the availability of effective means. Common methods of suicide include hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms. Suicides resulted in 828,000 deaths globally in 2015, an increase from 712,000 deaths in 1990. This makes suicide the 10th leading cause of death worldwide.

Approximately 1.5% of all deaths worldwide are by suicide. In a given year, this is roughly 12 per 100,000 people. Rates of suicide are generally higher among men than women, ranging from 1.5 times higher in the developing world to 3.5 times higher in the developed world. Suicide is generally most common among those over the age of 70; however, in certain countries, those aged between 15 and 30 are at the highest risk. Europe had the highest rates of suicide by region in 2015. There are an estimated 10 to 20 million non-fatal attempted suicides every year. Non-fatal suicide attempts may lead to injury and long-term disabilities. In the Western world, attempts are more common among young people and women.

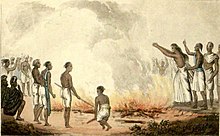

Views on suicide have been influenced by broad existential themes such as religion, honor, and the meaning of life. The Abrahamic religions traditionally consider suicide as an offense towards God due to the belief in the sanctity of life. During the samurai era in Japan, a form of suicide known as seppuku (腹切り, harakiri) was respected as a means of making up for failure or as a form of protest. Sati, a practice outlawed by the British in India, expected a Hindu widow to immolate herself on her husband's funeral pyre, either willingly or under pressure from her family and society. Suicide and attempted suicide, while previously illegal, are no longer so in most Western countries. It remains a criminal offense in some countries. In the 20th and 21st centuries, suicide has been used on rare occasions as a form of protest, and kamikaze and suicide bombings have been used as a military or terrorist tactic. Suicide is often seen as a major catastrophe for families, relatives, and other nearby supporters, and it is viewed negatively almost everywhere around the world.

Definitions

Suicide, derived from Latin suicidium, is "the act of taking one's own life". Attempted suicide or non-fatal suicidal behavior amounts to self-injury with at least some desire to end one's life that does not result in death. Assisted suicide occurs when one individual helps another bring about their own death indirectly via providing either advice or the means to the end. This is in contrast to euthanasia, where another person takes a more active role in bringing about a person's death. Suicidal ideation is thoughts of ending one's life but not taking any active efforts to do so. It may or may not involve exact planning or intent. In a murder–suicide (or homicide–suicide), the individual aims at taking the lives of others at the same time. A special case of this is extended suicide, where the murder is motivated by seeing the murdered persons as an extension of their self. Suicide in which the reason is that the person feels that they are not part of society is known as egoistic suicide.

In 2011, the Centre for Suicide Prevention in Canada found that the normal verb in scholarly research and journalism for the act of suicide was commit. On the other hand, the American Psychological Association lists "committed suicide" as a term to avoid because it "frame[s] suicide as a crime". Some advocacy groups recommend using the terms took his/her own life, died by suicide, or killed him/herself instead of committed suicide. The Associated Press Stylebook recommends avoiding "committed suicide" except in direct quotes from authorities. The Guardian and Observer style guides deprecate the use of "committed", as does CNN. Opponents of commit argue that it implies that suicide is criminal, sinful, or morally wrong.

Risk factors

Factors that affect the risk of suicide include mental disorders, drug misuse, psychological states, cultural, family and social situations, genetics, experiences of trauma or loss, and nihilism. Mental disorders and substance misuse frequently co-exist. Other risk factors include having previously attempted suicide, the ready availability of a means to take one's life, a family history of suicide, or the presence of traumatic brain injury. For example, suicide rates have been found to be greater in households with firearms than those without them.

Socio-economic problems such as unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and discrimination may trigger suicidal thoughts. Suicide might be rarer in societies with high social cohesion and moral objections against suicide. About 15–40% of people leave a suicide note. War veterans have a higher risk of suicide due in part to higher rates of mental illness, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, and physical health problems related to war. Genetics appears to account for between 38% and 55% of suicidal behaviors. Suicides may also occur as a local cluster of cases.

Most research does not distinguish between risk factors that lead to thinking about suicide and risk factors that lead to suicide attempts. Risks for suicide attempt rather than just thoughts of suicide include a high pain tolerance and a reduced fear of death.

Mental illness

Mental illness is present at the time of suicide 27% to more than 90% of the time. Of those who have been hospitalized for suicidal behavior, the lifetime risk of suicide is 8.6%. Comparatively, non-suicidal people hospitalized for affective disorders have a 4% lifetime risk of suicide. Half of all people who die by suicide may have major depressive disorder; having this or one of the other mood disorders such as bipolar disorder increases the risk of suicide 20-fold. Other conditions implicated include schizophrenia (14%), personality disorders (8%), obsessive–compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Those with autism also attempt and consider suicide more frequently.

Others estimate that about half of people who die by suicide could be diagnosed with a personality disorder, with borderline personality disorder being the most common. About 5% of people with schizophrenia die of suicide. Eating disorders are another high risk condition. Around 22% to 50% of people suffering with gender dysphoria have attempted suicide, however this greatly varies by region.

Among approximately 80% of suicides, the individual has seen a physician within the year before their death, including 45% within the prior month. Approximately 25–40% of those who died by suicide had contact with mental health services in the prior year. Antidepressants of the SSRI class appear to increase the frequency of suicide among children but do not change the risk among adults. An unwillingness to get help for mental health problems also increases the risk.

Previous attempts

A previous history of suicide attempts is the most accurate predictor of suicide. Approximately 20% of suicides have had a previous attempt, and of those who have attempted suicide, 1% die by suicide within a year and more than 5% die by suicide within 10 years.

Self-harm

Non-suicidal self-harm is common with 18% of people engaging in self-harm over the course of their life. Acts of self-harm are not usually suicide attempts and most who self-harm are not at high risk of suicide. Some who self-harm, however, do still end their life by suicide, and risk for self-harm and suicide may overlap. Individuals who have been identified as self-harming after being admitted to hospital are 68% (38–105%) more likely to die by suicide.

Psychosocial factors

A number of psychological factors increase the risk of suicide including: hopelessness, loss of pleasure in life, depression, anxiousness, agitation, rigid thinking, rumination, thought suppression, and poor coping skills. A poor ability to solve problems, the loss of abilities one used to have, and poor impulse control also play a role. In older adults, the perception of being a burden to others is important. Those who have never married are also at greater risk. Recent life stresses, such as a loss of a family member or friend or the loss of a job, might be a contributing factor.

Certain personality factors, especially high levels of neuroticism and introvertedness, have been associated with suicide. This might lead to people who are isolated and sensitive to distress to be more likely to attempt suicide. On the other hand, optimism has been shown to have a protective effect. Other psychological risk factors include having few reasons for living and feeling trapped in a stressful situation. Changes to the stress response system in the brain might be altered during suicidal states. Specifically, changes in the polyamine system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.

Social isolation and the lack of social support has been associated with an increased risk of suicide. Poverty is also a factor, with heightened relative poverty compared to those around a person increasing suicide risk. Over 200,000 farmers in India have died by suicide since 1997, partly due to issues of debt. In China, suicide is three times as likely in rural regions as urban ones, partly, it is believed, due to financial difficulties in this area of the country.

The time of year may also affect suicide rates. There appears to be a decrease around Christmas, but an increase in rates during spring and summer, which might be related to exposure to sunshine. Another study found that the risk may be greater for males on their birthday.

Being religious may reduce one's risk of suicide while beliefs that suicide is noble may increase it. This has been attributed to the negative stance many religions take against suicide and to the greater connectedness religion may give. Muslims, among religious people, appear to have a lower rate of suicide; however, the data supporting this is not strong. There does not appear to be a difference in rates of attempted suicide. Young women in the Middle East may have higher rates.

Substance misuse

Substance misuse is the second most common risk factor for suicide after major depression and bipolar disorder. Both chronic substance misuse as well as acute intoxication are associated. When combined with personal grief, such as bereavement, the risk is further increased. Substance misuse is also associated with mental health disorders.

Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide, with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases. Use of prescribed benzodiazepines is associated with an increased rate of suicide and attempted suicide. The pro-suicidal effects of benzodiazepines are suspected to be due to a psychiatric disturbance caused by side effects, such as disinhibition, or withdrawal symptoms. Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide. About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide. Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past. Between 3 and 35% of deaths among those who use heroin are due to suicide (approximately fourteenfold greater than those who do not use). In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.

The misuse of cocaine and methamphetamine has a high correlation with suicide. In those who use cocaine, the risk is greatest during the withdrawal phase. Those who used inhalants are also at significant risk with around 20% attempting suicide at some point and more than 65% considering it. Smoking cigarettes is associated with risk of suicide. There is little evidence as to why this association exists; however, it has been hypothesized that those who are predisposed to smoking are also predisposed to suicide, that smoking causes health problems which subsequently make people want to end their life, and that smoking affects brain chemistry causing a propensity for suicide. Cannabis, however, does not appear to independently increase the risk.

Medical conditions

There is an association between suicidality and physical health problems such as chronic pain, traumatic brain injury, cancer, chronic fatigue syndrome, kidney failure (requiring hemodialysis), HIV, and systemic lupus erythematosus. The diagnosis of cancer approximately doubles the subsequent frequency of suicide. The prevalence of increased suicidality persisted after adjusting for depressive illness and alcohol abuse. Among people with more than one medical condition the frequency was particularly high. In Japan, health problems are listed as the primary justification for suicide.

Sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and sleep apnea, are risk factors for depression and suicide. In some instances, the sleep disturbances may be a risk factor independent of depression. A number of other medical conditions may present with symptoms similar to mood disorders, including hypothyroidism, Alzheimer's, brain tumors, systemic lupus erythematosus, and adverse effects from a number of medications (such as beta blockers and steroids).

Occupational factors

Certain occupations carry an elevated risk of self-harm and suicide, such as military careers. Research in several countries has found that the rate of suicide among former armed forces personnel in particular, and young veterans especially, is markedly higher than that found in the general population.

Media

The media, including the Internet, plays an important role. Certain depictions of suicide may increase its occurrence, with high-volume, prominent, repetitive coverage glorifying or romanticizing suicide having the most impact. When detailed descriptions of how to kill oneself by a specific means are portrayed, this method of suicide can be imitated in vulnerable people. This phenomenon has been observed in several cases after press coverage. In a bid to reduce the adverse effect of media portrayals concerning suicide report, one of the effective methods is to educate journalists on how to report suicide news in a manner that might reduce that possibility of imitation and encourage those at risk to seek for help. When journalists follow certain reporting guidelines the risk of suicides can be decreased. Getting buy-in from the media industry, however, can be difficult, especially in the long term.

This trigger of suicide contagion or copycat suicide is known as the "Werther effect", named after the protagonist in Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther who killed himself and then was emulated by many admirers of the book. This risk is greater in adolescents who may romanticize death. It appears that while news media has a significant effect, that of the entertainment media is equivocal. It is unclear if searching for information about suicide on the Internet relates to the risk of suicide. The opposite of the Werther effect is the proposed "Papageno effect", in which coverage of effective coping mechanisms may have a protective effect. The term is based upon a character in Mozart's opera The Magic Flute—fearing the loss of a loved one, he had planned to kill himself until his friends helped him out. As a consequence, fictional portrayals of suicide, showing alternative consequences or negative consequences, might have a preventive effect, for instance fiction might normalize mental health problems and encourage help-seeking.

Other factors

Trauma is a risk factor for suicidality in both children and adults. Some may take their own lives to escape bullying or prejudice. A history of childhood sexual abuse and time spent in foster care are also risk factors. Sexual abuse is believed to contribute to approximately 20% of the overall risk. Significant adversity early in life has a negative effect on problem-solving skills and memory, both of which are implicated in suicidality.

Problem gambling is associated with increased suicidal ideation and attempts compared to the general population. Between 12 and 24% of pathological gamblers attempt suicide. The rate of suicide among their spouses is three times greater than that of the general population. Other factors that increase the risk in problem gamblers include concomitant mental illness, alcohol, and drug misuse.

Genetics might influence rates of suicide. A family history of suicide, especially in the mother, affects children more than adolescents or adults. Adoption studies have shown that this is the case for biological relatives, but not adopted relatives. This makes familial risk factors unlikely to be due to imitation. Once mental disorders are accounted for, the estimated heritability rate is 36% for suicidal ideation and 17% for suicide attempts. An evolutionary explanation for suicide is that it may improve inclusive fitness. This may occur if the person dying by suicide cannot have more children and takes resources away from relatives by staying alive. An objection is that deaths by healthy adolescents likely does not increase inclusive fitness. Adaptation to a very different ancestral environment may be maladaptive in the current one.

Infection by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, more commonly known as toxoplasmosis, has been linked with suicide risk. One explanation states that this is caused by altered neurotransmitter activity due to the immunological response.

There appears to be a link between air pollution and depression and suicide.

Rational

Rational suicide is the reasoned taking of one's own life. However, some consider suicide as never being rational.

Euthanasia and assisted suicide are accepted practices in a number of countries among those who have a poor quality of life without the possibility of getting better. They are supported by the legal arguments for a right to die.

The act of taking one's life for the benefit of others is known as altruistic suicide. An example of this is an elder ending his or her life to leave greater amounts of food for the younger people in the community. Suicide in some Inuit cultures has been seen as an act of respect, courage, or wisdom.

A suicide attack is a political or religious action where an attacker carries out violence against others which they understand will result in their own death. Some suicide bombers are motivated by a desire to obtain martyrdoms or are religiously motivated. Kamikaze missions were carried out as a duty to a higher cause or moral obligation. Murder–suicide is an act of homicide followed within a week by suicide of the person who carried out the act.

Mass suicides are often performed under social pressure where members give up autonomy to a leader. Mass suicides can take place with as few as two people, often referred to as a suicide pact. In extenuating situations where continuing to live would be intolerable, some people use suicide as a means of escape. Some inmates in Nazi concentration camps are known to have killed themselves during the Holocaust by deliberately touching the electrified fences.

Methods

The leading method of suicide varies among countries. The leading methods in different regions include hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms. These differences are believed to be in part due to availability of the different methods. A review of 56 countries found that hanging was the most common method in most of the countries, accounting for 53% of male suicides and 39% of female suicides.

Worldwide, 30% of suicides are estimated to occur from pesticide poisoning, most of which occur in the developing world. The use of this method varies markedly from 4% in Europe to more than 50% in the Pacific region. It is also common in Latin America due to the ease of access within the farming populations. In many countries, drug overdoses account for approximately 60% of suicides among women and 30% among men. Many are unplanned and occur during an acute period of ambivalence. The death rate varies by method: firearms 80–90%, drowning 65–80%, hanging 60–85%, jumping 35–60%, charcoal burning 40–50%, pesticides 60–75%, and medication overdose 1.5–4.0%. The most common attempted methods of suicide differ from the most common methods of completion; up to 85% of attempts are via drug overdose in the developed world.

In China, the consumption of pesticides is the most common method. In Japan, self-disembowelment known as seppuku (harakiri) still occurs; however, hanging and jumping are the most common. Jumping to one's death is common in both Hong Kong and Singapore at 50% and 80% respectively. In Switzerland, firearms are the most frequent suicide method in young males, although this method has decreased since guns have become less common. In the United States, 50% of suicides involve the use of firearms, with this method being somewhat more common in men (56%) than women (31%). The next most common cause was hanging in males (28%) and self-poisoning in females (31%). Together, hanging and poisoning constituted about 42% of U.S. suicides (as of 2017).

Pathophysiology

There is no known unifying underlying pathophysiology for suicide; it is believed to result from an interplay of behavioral, socio-economic and psychological factors.

Low levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are both directly associated with suicide and indirectly associated through its role in major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Post-mortem studies have found reduced levels of BDNF in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, in those with and without psychiatric conditions. Serotonin, a brain neurotransmitter, is believed to be low in those who die by suicide. This is partly based on evidence of increased levels of 5-HT2A receptors found after death. Other evidence includes reduced levels of a breakdown product of serotonin, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, in the cerebral spinal fluid. However, direct evidence is hard to obtain. Epigenetics, the study of changes in genetic expression in response to environmental factors which do not alter the underlying DNA, is also believed to play a role in determining suicide risk.

Prevention

Suicide prevention is a term used for the collective efforts to reduce the incidence of suicide through preventive measures. Protective factors for suicide include support, and access to therapy. About 60% of people with suicidal thoughts do not seek help. Reasons for not doing so include low perceived need, and wanting to deal with the problem alone. Despite these high rates, there are few established treatments available for suicidal behavior.

Reducing access to certain methods, such as firearms or toxins such as opioids and pesticides, can reduce risk of suicide by that method. This may be in part because suicide is often an impulsive decision, with up to 70% of near-fatal suicide attempts made after less than one hour of deliberation—thus, reducing access to easily-accessible methods of suicide may make impulsive attempts less likely to succeed. Other measures include reducing access to charcoal (for burning) and adding barriers on bridges and subway platforms. Treatment of drug and alcohol addiction, depression, and those who have attempted suicide in the past, may also be effective. Some have proposed reducing access to alcohol as a preventive strategy (such as reducing the number of bars).

In young adults who have recently thought about suicide, cognitive behavioral therapy appears to improve outcomes. School-based programs that increase mental health literacy and train staff have shown mixed results on suicide rates. Economic development through its ability to reduce poverty may be able to decrease suicide rates. Efforts to increase social connection, especially in elderly males, may be effective. In people who have attempted suicide, following up on them might prevent repeat attempts. Although crisis hotlines are common, there is little evidence to support or refute their effectiveness. Preventing childhood trauma provides an opportunity for suicide prevention. The World Suicide Prevention Day is observed annually on 10 September with the support of the International Association for Suicide Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Screening

IS PATH WARM [...] is an acronym [...] to assess [...] a potentially suicidal individual, (i.e., ideation, substance abuse, purposelessness, anger, feeling trapped, hopelessness, withdrawal, anxiety, recklessness, and mood).

— American Association of Suicidology (2019)

There is little data on the effects of screening the general population on the ultimate rate of suicide. Screening those who come to the emergency departments with injuries from self-harm have been shown to help identify suicide ideation and suicide intention. Psychometric tests such as the Beck Depression Inventory or the Geriatric Depression Scale for older people are being used. As there is a high rate of people who test positive via these tools that are not at risk of suicide, there are concerns that screening may significantly increase mental health care resource utilization. Assessing those at high risk, though, is recommended. Asking about suicidality does not appear to increase the risk.

Mental illness

In those with mental health problems, a number of treatments may reduce the risk of suicide. Those who are actively suicidal may be admitted to psychiatric care either voluntarily or involuntarily. Possessions that may be used to harm oneself are typically removed. Some clinicians get patients to sign suicide prevention contracts where they agree to not harm themselves if released. However, evidence does not support a significant effect from this practice. If a person is at low risk, outpatient mental health treatment may be arranged. Short-term hospitalization has not been found to be more effective than community care for improving outcomes in those with borderline personality disorder who are chronically suicidal.

There is tentative evidence that psychotherapy, specifically dialectical behaviour therapy, reduces suicidality in adolescents as well as in those with borderline personality disorder. It may also be useful in decreasing suicide attempts in adults at high risk. However, a decrease in suicide has not been observed.

There is controversy around the benefit-versus-harm of antidepressants. In young persons, some antidepressants, such as SSRIs, appear to increase the risk of suicidality from 25 per 1000 to 40 per 1000. In older persons, however, they may decrease the risk. Lithium appears effective at lowering the risk in those with bipolar disorder and major depression to nearly the same levels as that of the general population. Clozapine may decrease the thoughts of suicide in some people with schizophrenia. Ketamine, which is a dissociative anaesthetic, seems to lower the rate of suicidal ideation. In the United States, health professionals are legally required to take reasonable steps to try to prevent suicide.

Epidemiology

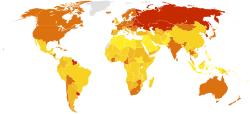

Approximately 1.4% of people die by suicide, a mortality rate of 11.6 per 100,000 persons per year. Suicide resulted in 842,000 deaths in 2013 up from 712,000 deaths in 1990. Rates of suicide have increased by 60% from the 1960s to 2012, with these increases seen primarily in the developing world. Globally, as of 2008/2009, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death. For every suicide that results in death there are between 10 and 40 attempted suicides.

Suicide rates differ significantly between countries and over time. As a percentage of deaths in 2008 it was: Africa 0.5%, South-East Asia 1.9%, Americas 1.2% and Europe 1.4%. Rates per 100,000 were: Australia 8.6, Canada 11.1, China 12.7, India 23.2, United Kingdom 7.6, United States 11.4 and South Korea 28.9. It was ranked as the 10th leading cause of death in the United States in 2016 with about 45,000 cases that year. Rates have increased in the United States in the last few years, with the highest value being in 2017 (the most recent data). In the United States, about 650,000 people are seen in emergency departments yearly due to attempting suicide. The United States rate among men in their 50s rose by nearly half in the decade 1999–2010. Greenland, Lithuania, Japan, and Hungary have the highest rates of suicide. Around 75% of suicides occur in the developing world. The countries with the greatest absolute numbers of suicides are China and India, partly due to their large population size, accounting for over half the total. In China, suicide is the 5th leading cause of death.

Sex and gender

Globally as of 2012, death by suicide occurs about 1.8 times more often in males than females. In the Western world, males die three to four times more often by means of suicide than do females. This difference is even more pronounced in those over the age of 65, with tenfold more males than females dying by suicide. Suicide attempts and self-harm are between two and four times more frequent among females. Researchers have attributed the difference between suicide and attempted suicide among the sexes to males using more lethal means to end their lives. However, separating intentional suicide attempts from non-suicidal self-harm is not currently done in places like the United States when gathering statistics at the national level.

China has one of the highest female suicide rates in the world and is the only country where it is higher than that of men (ratio of 0.9). In the Eastern Mediterranean, suicide rates are nearly equivalent between males and females. The highest rate of female suicide is found in South Korea at 22 per 100,000, with high rates in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific generally.

A number of reviews have found an increased risk of suicide among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. Among transgender persons, rates of attempted suicide are about 40% compared to a general population rate of 5%. This is believed to in part be due to social stigmatisation.

Age

In many countries, the rate of suicide is highest in the middle-aged or elderly. The absolute number of suicides, however, is greatest in those between 15 and 29 years old, due to the number of people in this age group. Worldwide, the average age of suicide is between age 30 and 49 for both men and women. This means that half of people who died by suicide were approximately age 40 or younger, and half were older. Suicidality is rare in children, but increases during the transition to adolescence.

In the United States, the suicide death rate is greatest in Caucasian men older than 80 years, even though younger people more frequently attempt suicide. It is the second most common cause of death in adolescents and in young males is second only to accidental death. In young males in the developed world, it is the cause of nearly 30% of mortality. In the developing world rates are similar, but it makes up a smaller proportion of overall deaths due to higher rates of death from other types of trauma. In South-East Asia, in contrast to other areas of the world, deaths from suicide occur at a greater rate in young females than elderly females.

History

In ancient Athens, a person who died by suicide without the approval of the state was denied the honors of a normal burial. The person would be buried alone, on the outskirts of the city, without a headstone or marker. However, it was deemed to be an acceptable method to deal with military defeat. In Ancient Rome, while suicide was initially permitted, it was later deemed a crime against the state due to its economic costs. Aristotle condemned all forms of suicide while Plato was ambivalent. In Rome, some reasons for suicide included volunteering death in a gladiator combat, guilt over murdering someone, to save the life of another, as a result of mourning, from shame from being raped, and as an escape from intolerable situations like physical suffering, military defeat, or criminal pursuit.

Suicide came to be regarded as a sin in Christian Europe and was condemned at the Council of Arles (452) as the work of the Devil. In the Middle Ages, the Church had drawn-out discussions as to when the desire for martyrdom was suicidal, as in the case of martyrs of Córdoba. Despite these disputes and occasional official rulings, Catholic doctrine was not entirely settled on the subject of suicide until the later 17th century. A criminal ordinance issued by Louis XIV of France in 1670 was extremely severe, even for the times: the dead person's body was drawn through the streets, face down, and then hung or thrown on a garbage heap. Additionally, all of the person's property was confiscated.

Attitudes towards suicide slowly began to shift during the Renaissance. John Donne's work Biathanatos contained one of the first modern defences of suicide, bringing proof from the conduct of Biblical figures, such as Jesus, Samson and Saul, and presenting arguments on grounds of reason and nature to sanction suicide in certain circumstances.

The secularization of society that began during the Enlightenment questioned traditional religious attitudes (such as Christian views on suicide) toward suicide and brought a more modern perspective to the issue. David Hume denied that suicide was a crime as it affected no one and was potentially to the advantage of the individual. In his 1777 Essays on Suicide and the Immortality of the Soul he rhetorically asked, "Why should I prolong a miserable existence, because of some frivolous advantage which the public may perhaps receive from me?" Hume's analysis was criticized by philosopher Philip Reed as being "uncharacteristically (for him) bad", since Hume took an unusually narrow conception of duty and his conclusion depended upon the suicide producing no harm to others – including causing no grief, feelings of guilt, or emotional pain to any surviving friends and family – which is almost never the case. A shift in public opinion at large can also be discerned; The Times in 1786 initiated a spirited debate on the motion "Is suicide an act of courage?".

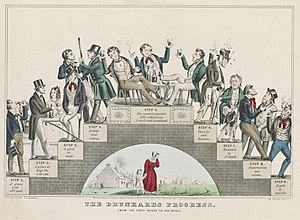

By the 19th century, the act of suicide had shifted from being viewed as caused by sin to being caused by insanity in Europe. Although suicide remained illegal during this period, it increasingly became the target of satirical comments, such as the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera The Mikado, which satirized the idea of executing someone who had already killed himself.

By 1879, English law began to distinguish between suicide and homicide, although suicide still resulted in forfeiture of estate. In 1882, the deceased were permitted daylight burial in England and by the middle of the 20th century, suicide had become legal in much of the Western world. The term suicide first emerged shortly before 1700 to replace expressions on self-death which were often characterized as a form of self-murder in the West.

Social and culture

Legislation

No country in Europe currently considers suicide or attempted suicide to be a crime. It was, however, in most Western European countries from the Middle Ages until at least the 19th century. The Netherlands was the first country to legalize both physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, which took effect in 2002, although only doctors are allowed to assist in either of them, and have to follow a protocol prescribed by Dutch law. If such protocol is not followed, it is an offence punishable by law. In Germany, active euthanasia is illegal and anyone present during suicide may be prosecuted for failure to render aid in an emergency. Switzerland has taken steps to legalize assisted suicide for the chronically mentally ill. The high court in Lausanne, Switzerland, in a 2006 ruling, granted an anonymous individual with longstanding psychiatric difficulties the right to end his own life. England and Wales decriminalized suicide via the Suicide Act 1961 and the Republic of Ireland in 1993. The word "commit" was used in reference to its being illegal, but many organisations have stopped it because of the negative connotation.

In the United States, suicide is not illegal, but may be associated with penalties for those who attempt it. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in the state of Washington for people with terminal diseases. In Oregon, people with terminal diseases may request medications to help end their life. Canadians who have attempted suicide may be barred from entering the United States. U.S. laws allow border guards to deny access to people who have a mental illness, including those with previous suicide attempts.

In Australia, suicide is not a crime. However, it is a crime to counsel, incite, or aid and abet another in attempting to die by suicide, and the law explicitly allows any person to use "such force as may reasonably be necessary" to prevent another from taking their own life. The Northern Territory of Australia briefly had legal physician-assisted suicide from 1996 to 1997.

In India, suicide was illegal until 2014, and surviving family members used to face legal difficulties. It remains a criminal offense in most Muslim-majority nations.

In Malaysia, suicide per se is not a crime; however, attempted suicide is. Under Section 309 of the Penal Code, a person convicted of attempting suicide can be punished with imprisonment of up to one year, fined, or both. There are ongoing efforts to decriminalise attempted suicide, although rights groups and non-governmental organisations such as the local chapter of Befrienders note that progress has been slow. Proponents of decriminalisation argue that suicide legislation may deter people from seeking help, and may even strengthen the resolve of would-be suicides to end their lives to avoid prosecution.

Religious views

Christianity

Most forms of Christianity consider suicide sinful, based mainly on the writings of influential Christian thinkers of the Middle Ages, such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, but suicide was not considered a sin under the Byzantine Christian code of Justinian, for instance. In Catholic and Orthodox doctrine, suicide is considered to be murder, violating the commandment "Thou shalt not kill," and historically neither church would even hold a burial service for a member that died by suicide, deeming it an act that condemned the person to hell, since they died in a state of mortal sin. The basic idea being that life is a gift given by God which should not be spurned, and that suicide is against the "natural order" and thus interferes with God's master plan for the world. However, it is believed that mental illness or grave fear of suffering diminishes the responsibility of the one completing suicide.

Judaism

Judaism focuses on the importance of valuing this life, and as such, suicide is tantamount to denying God's goodness in the world. Despite this, under extreme circumstances when there has seemed no choice but to either be killed or forced to betray their religion, there are several accounts of Jews having died by suicide, either individually or in groups (see Holocaust, Masada, First French persecution of the Jews and York Castle for examples), and as a grim reminder there is even a prayer in the Jewish liturgy for "when the knife is at the throat", for those dying "to sanctify God's Name" (see Martyrdom). These acts have received mixed responses by Jewish authorities, regarded by some as examples of heroic martyrdom, while others state that it was wrong for them to take their own lives in anticipation of martyrdom.

Islam

Islamic religious views are against suicide. The Quran forbids it by stating "do not kill or destroy yourself". The hadiths also state individual suicide to be unlawful and a sin. Stigma is often associated with suicide in Islamic countries.

Hinduism and Jainism

In Hinduism, suicide is generally disdained and is considered equally sinful as murdering another in contemporary Hindu society. Hindu Scriptures state that one who dies by suicide will become part of the spirit world, wandering earth until the time one would have otherwise died, had one not taken one's own life. However, Hinduism accepts a man's right to end one's life through the non-violent practice of fasting to death, termed Prayopavesa; but Prayopavesa is strictly restricted to people who have no desire or ambition left, and no responsibilities remaining in this life.

Jainism has a similar practice named Santhara. Sati, or self-immolation by widows, is a rare and illegal practice in Hindu society.

Ainu

Within the Ainu religion, someone who dies by suicide is believed to become a ghost (tukap) who would haunt the living, to come to fulfillment from which they were excluded during life. Also, someone who insults another so they kill themselves is regarded as co-responsible for their death. According to Norbert Richard Adami, this ethic exists due to the case that solidarity within the community is much more important to Ainu culture than it is to the Western world.

Philosophy

A number of questions are raised within the philosophy of suicide, including what constitutes suicide, whether or not suicide can be a rational choice, and the moral permissibility of suicide. Arguments as to acceptability of suicide in moral or social terms range from the position that the act is inherently immoral and unacceptable under any circumstances, to a regard for suicide as a sacrosanct right of anyone who believes they have rationally and conscientiously come to the decision to end their own lives, even if they are young and healthy.

Opponents to suicide include philosophers such as Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas, Immanuel Kant and, arguably, John Stuart Mill – Mill's focus on the importance of liberty and autonomy meant that he rejected choices which would prevent a person from making future autonomous decisions. Others view suicide as a legitimate matter of personal choice. Supporters of this position maintain that no one should be forced to suffer against their will, particularly from conditions such as incurable disease, mental illness, and old age, with no possibility of improvement. They reject the belief that suicide is always irrational, arguing instead that it can be a valid last resort for those enduring major pain or trauma. A stronger stance would argue that people should be allowed to autonomously choose to die regardless of whether they are suffering. Notable supporters of this school of thought include Scottish empiricist David Hume, who accepted suicide so long as it did not harm or violate a duty to God, other people, or the self, and American bioethicist Jacob Appel.

Advocacy

Advocacy of suicide has occurred in many cultures and subcultures. The Japanese military during World War II encouraged and glorified kamikaze attacks, which were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific Theater of World War II. Japanese society as a whole has been described as "suicide-tolerant" (see Suicide in Japan).

Internet searches for information on suicide return webpages that 10–30% of the time encourage or facilitate suicide attempts. There is some concern that such sites may push those predisposed over the edge. Some people form suicide pacts online, either with pre-existing friends or people they have recently encountered in chat rooms or message boards. The Internet, however, may also help prevent suicide by providing a social group for those who are isolated.

Locations

Some landmarks have become known for high levels of suicide attempts. These include China's Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge, Japan's Aokigahara Forest, England's Beachy Head, and Toronto's Bloor Street Viaduct. As of 2010, the Golden Gate Bridge has had more than 1,300 suicides by jumping since its construction in 1937. Many locations where suicide is common have constructed barriers to prevent it; this includes the Luminous Veil in Toronto, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the West Gate Bridge in Melbourne, and Empire State Building in New York City. They generally appear to be effective.

Notable cases

An example of mass suicide is the 1978 Jonestown mass murder/suicide in which 909 members of the Peoples Temple, an American new religious movement led by Jim Jones, ended their lives by drinking grape Flavor Aid laced with cyanide and various prescription drugs.

Thousands of Japanese civilians took their own lives in the last days of the Battle of Saipan in 1944, some jumping from "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff". The 1981 Irish hunger strikes, led by Bobby Sands, resulted in 10 deaths. The cause of death was recorded by the coroner as "starvation, self-imposed" rather than suicide; this was modified to simply "starvation" on the death certificates after protest from the dead strikers' families. During World War II, Erwin Rommel was found to have foreknowledge of the 20 July plot on Hitler's life; he was threatened with public trial, execution, and reprisals on his family unless he killed himself.

Other species

As suicide requires a willful attempt to die, some feel it therefore cannot be said to occur in non-human animals. Suicidal behavior has been observed in Salmonella seeking to overcome competing bacteria by triggering an immune system response against them. Suicidal defenses by workers are also noted in the Brazilian ant Forelius pusillus, where a small group of ants leaves the security of the nest after sealing the entrance from the outside each evening.

Pea aphids, when threatened by a ladybug, can explode themselves, scattering and protecting their brethren and sometimes even killing the ladybug; this form of suicidal altruism is known as autothysis. Some species of termites (for example Globitermes sulphureus) have soldiers that explode, covering their enemies with sticky goo.

There have been anecdotal reports of dogs, horses, and dolphins killing themselves, but little scientific study of animal suicide. Animal suicide is usually put down to romantic human interpretation and is not generally thought to be intentional. Some of the reasons animals are thought to unintentionally kill themselves include: psychological stress, infection by certain parasites or fungi, or disruption of a long-held social tie, such as the ending of a long association with an owner and thus not accepting food from another individual.

![Death rate from suicide per 100,000 as of 2017[203]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Death_rate_from_suicides_%28IHME_%281990_to_2016%29%29%2C_OWID.svg/312px-Death_rate_from_suicides_%28IHME_%281990_to_2016%29%29%2C_OWID.svg.png)

![Share of deaths from suicide, 2017[204]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/Share_of_deaths_from_suicide%2C_OWID.svg/312px-Share_of_deaths_from_suicide%2C_OWID.svg.png)