| Video game addiction | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gaming disorder, internet gaming disorder, problematic online gaming |

| |

| Symptoms | Problem gambling, depression, social withdrawal, playing video games for extremely long periods of time |

| Complications | Mood disorders, depression, somatisation, sleep disturbances, obesity, anxiety disorders |

| Risk factors | Preexisting mental disorder (ADHD, OCD, compulsive behavior, conduct disorder, depression, behavioral inhibition), personality traits (neuroticism, impulsivity, aggressiveness) |

| Frequency | 1–3% of those who play video games |

Video game addiction (VGA), also known as gaming disorder or internet gaming disorder, is generally defined as a psychological addiction that is problematic, compulsive use of video games that results in significant impairment to an individual's ability to function in various life domains over a prolonged period of time. This and associated concepts have been the subject of considerable research, debate, and discussion among experts in several disciplines and has generated controversy within the medical, scientific, and gaming communities. Such disorders can be diagnosed when an individual engages in gaming activities at the cost of fulfilling daily responsibilities or pursuing other interests without regard for the negative consequences. As defined by the ICD-11, the main criterion for this disorder is a lack of self control over gaming.

The World Health Organization included gaming disorder in the 11th revision of its International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The American Psychiatric Association (APA), while stating there is insufficient evidence for the inclusion of Internet gaming disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 2013, considered it worthy of further study.

Controversy around the diagnosis includes whether the disorder is a separate clinical entity or a manifestation of underlying psychiatric disorders. Research has approached the question from a variety of viewpoints, with no universally standardized or agreed definitions, leading to difficulties in developing evidence-based recommendations.

Definition and diagnosis

In its report, the Council on Science and Public Health to the American Medical Association (AMA) used this two-hour-per-day limit to define "gaming overuse", citing the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline of no more than one to two hours per day of "screen time". However, the ESA document cited in the Council report does not contain the two-hour-per-day data.

American Psychiatric Association

While the American Psychiatric Association (APA) does not recognise video game addiction as a disorder, in light of existing evidence, the organisation included video game addiction as a "condition requiring further study" in the DSM-5 as Internet gaming disorder. Video game addiction is a broader concept than internet gaming addiction, but most video game addiction is associated with internet gaming. APA suggests, like Khan, the effects (or symptoms) of video game addiction may be similar to those of other proposed psychological addictions. Video game addiction may be an impulse control disorder, similar to compulsive gambling The APA explains why Internet Gaming Disorder has been proposed as a disorder:

This decision was based upon the large number of studies of this condition and the severity of its consequences. ... Because of the distinguishing features and increased risks of clinically significant problems associated with gaming in particular, the Workgroup recommended the inclusion of only internet gaming disorder in Section 3 of the DSM-5.

Some players become more concerned with their interactions in the game than in their broader lives. Players may play many hours per day, neglect personal hygiene, gain or lose significant weight, disrupt sleep patterns resulting in sleep deprivation, play at work, avoid phone calls from friends, or lie about how much time they spend playing video games.

The APA has developed nine criteria for characterising the proposed Internet Gaming Disorder:

- Pre-occupation. Do you spend a lot of time thinking about games even when you are not playing, or planning when you can play next?

- Withdrawal. Do you feel restless, irritable, moody, angry, anxious or sad when attempting to cut down or stop gaming, or when you are unable to play?

- Tolerance. Do you feel the need to play for increasing amounts of time, play more exciting games, or use more powerful equipment to get the same amount of excitement you used to get?

- Reduce/stop. Do you feel that you should play less, but are unable to cut back on the amount of time you spend playing games?

- Give up other activities. Do you lose interest in or reduce participation in other recreational activities due to gaming?

- Continue despite problems. Do you continue to play games even though you are aware of negative consequences, such as not getting enough sleep, being late to school/work, spending too much money, having arguments with others, or neglecting important duties?

- Deceive/cover up. Do you lie to family, friends or others about how much you game, or try to keep your family or friends from knowing how much you game?

- Escape adverse moods. Do you game to escape from or forget about personal problems, or to relieve uncomfortable feelings such as guilt, anxiety, helplessness or depression?

- Risk/lose relationships/opportunities. Do you risk or lose significant relationships, or job, educational or career opportunities because of gaming?

One of the most commonly used instruments for the measurement of addiction, the PVP Questionnaire (Problem Video Game Playing Questionnaire, Tejeiro & Moran, 2002), was presented as a quantitative measure, not as a diagnostic tool. According to Griffiths, "all addictions (whether chemical or behavioral) are essentially about constant rewards and reinforcement". He proposes that addiction has six components: salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse. But the APA's nine criteria for diagnosing Internet Gaming Disorder were made by taking point of departure in eight different diagnostic/measuring tools proposed in other studies. Thus, the APA's criteria attempt to condense the scientific work on diagnosing Internet Gaming Disorder.

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) had proposed and later included "gaming disorder" in the 11th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11), released in June 2018, which was approved by the World Health Assembly in May 2019. The use and enforcement of ICD-11 is expected to start on 1 January 2022.

Screening tools

The first psychometric test to assess IGD was the Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGD-20). This test includes 20 questions designed to assess the extent of problems caused by disordered gaming and the degree of symptoms experienced by gamers. The test was first published in a journal article published in the PLoS ONE journal on 14 October 2014.

The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form (IGDS9-SF) is a short psychometric test to assess video game addiction according to the American Psychiatric Association framework for IGD. Recent review studies suggest that the IGDS9-SF presents with robust empirical and clinical evidence and is an effective tool to assess IGD. Moreover, the scale was adapted in several languages as Spanish, Chinese, Czech, German, and many more.

On 3 June 2019, a screening tool for Gaming Disorder, specifically as defined by the World Health Organization, called the "Gaming Disorder Test" was published in a journal article.

Risk factors

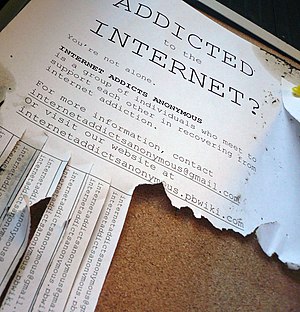

The Internet can foster various addictions including addiction to gameplaying.

Addictive playing of MMORPGs is associated with negative effects, whereas normal play is not.

Younger people and men are more likely to experience a gaming disorder than older people and women respectively. Research shows that the average age of a gamer is 30 years old, and 32% of players are under 18.Adolescents are at a higher risk of sustaining video game disorder over time than adults. An international meta-analysis over 34 jurisdictions quantified the effect size of gender as small, with most effect in Asia, lesser in Europe and Africa, and null in North America, and further finding that economic factors, internet availability, social norms and addiction-related health factors mediate the effect of gender, with nations with a greater GDP per capita having less differences in video game addiction between genders.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders act as both risk factors and consequences. Indeed, there is a strong association between video game addiction and anxiety, depression, ADHD, social phobia, and poor psycho-social support. ADHD and its symptoms, such as impulsivity and conduct problems, also increase risks of developing video game disorder. Although internet gaming disorder has a strong relationship with obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is not specific and internet gaming disorder is both phenomenologically and neurobiologically distinct, which indicates that internet gaming disorder is more characterized by impulsivity than compulsivity. Familial factors appear to play an important role, although not well understood.

Some personality traits, such as high neuroticism, high impulsivity, and high aggressiveness are consistently significant predictors of internet gaming disorder, and combination of personality traits seem to play a pivotal role in the acquisition, maintenance and development of the disorder.

Mechanisms

Although there is much research since the 1980s on problematic online gaming use, the mechanisms are not well understood, due to inconsistent definitions used in studies.

Video game structure

Some theories focus on the presumed built-in reward systems of video games, such as compulsion loops, to explain their potentially addictive nature. The anticipation of such rewards can create a neurological reaction that releases dopamine in the body, so that once the reward is obtained, the person will remember it as a pleasurable feeling. This has been found to be similar to the neurological reaction of other behavioral addictions such as substance abuse and gambling disorder.

Mark Griffiths has proposed another reason online video games are potentially addictive is because they "can be played all day every day." The fact there is no end to the game can feel rewarding for some, and hence players are further engaged in the game.

Addiction circuits in the brain

Long-term internet video/mobile game playing affects brain regions responsible for reward, impulse control and sensory-motor coordination. Structural analyses shown modifications in the volume of the ventral striatum, possibly as result of changes in rewards, and video game addicts had faulty inhibitory control and reward mechanisms. Video game playing is associated with dopamine release similar in magnitude to that of drug abuse and gambling, and the presentation of gaming pictures activates brain regions similarly to drug pictures for drug addicts. Treatment studies which used fMRI to monitor the brain connectivity changes found a decrease in the activity of the regions associated with cravings. Although there are evidences that video game addiction may be supported by similar neural mechanisms underlying drug abuse, as video game and internet addictions reduce the sensitivity of the dopaminergic reward system, it is still premature to conclude that this addiction is equivalent to substance addictions, as the research is in its early stages. There is evidence of a dual processing model of digital technology addictions characterized by an imbalance between the reactive and the reflective reward systems. Other studies shown increased difficulties in decision making in specific contexts, such as risky situations but not in ambiguous situations, and an increased preference for short-term rewards. Although the number of neuroimaging studies on internet gaming disorder is rising, there are several methodological shortcomings, particularly in the inconsistency of psychometric assessments. Furthermore, the conclusions on reduced inhibition should be moderated, as only one study included a functional control, which then showed no difference in inhibition.

A meta-analytic review of the research concluded the evidence suggests video game addiction arises out of other mental health problems, rather than causing them. Thus it is unclear whether video game addiction should be considered a unique diagnosis.

Management

As concern over video game addiction grows, the use of psychopharmacology, psychotherapy, twelve-step programs, and use of continuing developing treatment enhancements have been proposed to treat this disorder. Empirical studies indeed indicate that internet gaming disorder is associated with detrimental health-related outcomes. However, the clinical trials of potential treatments remain of low quality, except for cognitive-behavioral therapies, which shows efficacy to reduce gaming disorder and depressive symptoms but not total time spent. Although there is a scientific consensus that cognitive-behavioral therapy is preferable to pharmacological treatment, it remains difficult to make definitive statements about its benefits and efficiency due to methodological inconsistencies and lack of follow-up. Since efficacious treatments have not been well established, prevention of video gaming disorder is crucial. Some evidence suggest that up to 50% of people affected by the internet gaming disorder may recover naturally.

Some countries, such as South Korea, China, the Netherlands, Canada, and the United States, have responded to the perceived threat of video game addiction by opening treatment centres.

China

China was the first country to treat "internet addiction" clinically in 2008. The Chinese government operates several clinics to treat those who overuse online games, chatting and web surfing. Treatment for the patients, most of whom have been forced to attend by parents or government officials, includes various forms of pain including shock therapy. In August 2009, Deng Sanshan was reportedly beaten to death in a correctional facility for video game and Web addiction. Most of the addiction "boot camps" in China are actually extralegal militaristically managed centers, but have remained popular despite growing controversy over their practices.

In 2019, China set up a curfew, banning minors from playing between certain hours. In 2021, China government published a new policy to force corporations to only serve underage teenagers on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday between 8 pm to 9 pm.

Netherlands

In June 2006, the Smith and Jones clinic in Amsterdam—which has now gone bankrupt—became the first treatment facility in Europe to offer a residential treatment program for compulsive gamers. Keith Bakker, founder and former head of the clinic, has stated that 90% of the young people who seek treatment for compulsive computer gaming are not addicted.

Canada

At a Computer Addiction Services center in Richmond, British Columbia, excessive gaming accounts for 80% of one youth counselor's caseload.

United Kingdom

In 2018, the National Health Service announced its plans to open a treatment center, run by the Central and North West London NHS foundation trust, that will initially focus on gaming disorder, but is planned to expand to cover other internet-based addictions. The specialist treatment center opened in 2019 for treating adolescents and young people aged 13–25 who are addicted to video games.

Outcomes

Physical health

The most frequent physical health-related outcome are alterations in physical functioning such as somatization and sleep disturbances. Preliminary evidence suggest that internet gaming disorder and the induced sedentarity may contribute to a lack of physical exercise, even though the relationship is not causal.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of internet gaming disorder range from 0.7% to 25.5% worldwide, or 1.0% to 26.8% worldwide, and 3.5% to 17% in China, and is higher among males than females and among younger than older people, with geographical region being an insignificant contributor. The prevalence was found to be 5.06% among a high-school student population from Sri Lanka, suggesting an increasing trend in low- and middle-income countries as well. A longer time spent on video games predicts a tendency towards pathological gaming in the future. The studies, however, used various methodologies and definitions, which renders consensus difficult to achieve and may explain the wide range of prevalence.

Research

Debates on the classification

A meta-analytic review of pathological gaming studies concluded that about 3% of gamers may experience some symptoms of pathological gaming. The report noted problems in the field with defining and measuring pathological gaming and concluded that pathological gaming behaviors were more likely the product of underlying mental health problems rather than the inverse.

Barnett and Coulson expressed concern that much of the debate on the issue of addiction may be a knee jerk response stimulated by poor understanding of games and game players. Such issues may lead both society and scholars to exaggerate the prevalence and nature of problematic gaming, and over-focus on games specifically, while ignoring underlying mental health issues. However, Problem gamblers have a higher chance for getting mental illness as well.

Other scholars have cautioned that comparing the symptoms of problematic gaming with problematic gambling is flawed, and that such comparisons may introduce research artifacts and artificially inflate prevalence estimates. For instance, Richard Wood has observed that behaviors which are problematic in regards to gambling may not be as problematic when put into the context of other behaviors that are rewarding such as gaming. Similarly, Barnett and Coulson have cautioned that discussions of problematic gaming have moved forward prematurely without proper understanding of the symptoms, proper assessment and consequences.

Rather than video gaming disorder being a subtype of gambling disorder, a majority of researchers support the idea of video game addiction being a part of a more comprehensive framework of impulse control disorders with "pathological technology use" with similar characteristics, including the pathological use of video games, internet, computers and other interactive medias. Although internet and video game addictions are generally considered different from gambling disorder and substance abuse, there is a growing body of evidence indicating they share common features, including behavioral and neural features. Indeed, it is suggested that while behavioral addiction may differ with drug addictions in magnitude, they share several characteristics, with Hellman et al. proposing that the concept of addiction should be de-medicalized.

On the contrary, a literature review found that as the video game addiction develops, online gaming addicts spend increasing amounts of time not only playing but also preparing for and organizing their playing sessions, suggesting this addiction may be behavioral rather than a disorder of impulse control. There is recent evidence suggesting that internet gaming disorder can cause two distinct types of dysfunctions: cognitive and metacognitive.

Griffiths has suggested that psycho-social dependence may revolve around the intermittent reinforcements in the game and the need to belong. Hagedorn & Young have suggested that social dependence may arise due to video games occurring online where players interact with others and the relationships "often become more important for gamers than real-life relationships".

Controversy and alternative viewpoints

Common challenges involve the reliability of the methodology and validity of the results in some studies. Many rely on self-surveys from university students and also lack time frames making it difficult to study the impact, if any, of addiction on a long term scale. Other concerns also address the definition of addiction and how to measure it, questioning whether or not time is a proper unit to determine how addicted someone is to gaming. Daria Joanna Kuss and Mark D. Griffiths have argued the current scientific knowledge on internet gaming addiction is copious in scope and complexity. They state that instead, a simple framework should be provided to allow all current and future studies to be categorized, as internet gaming addiction lies on a continuum beginning with etiology and risk factors all the way through the development of "full-blown" addiction and ending with ramifications and potential treatment. In addition, they caution the deployment of the label "addiction" since it heavily denotes the use of substances or engagement in certain behaviors. Finally, the researcher promotes other researchers to assess the validity and reliability of existing measures instead of developing additional measurement instruments.

Other challenges include the lack of context of the participant's life and the negative portrayal of gaming addicts. Some state that gamers sometimes use video games to either escape from an uncomfortable environment or alleviate their already existing mental issues—both possibly important aspects in determining the psychological impact of gaming. Negative portrayal also deals with the lack of consistency in measuring addictive gaming. This leads to discussions that sometimes exaggerate the issue and create a misconception in some that they, themselves, may be addicted when they are not.

The evidence of video game addiction to create withdrawal symptoms is very limited and thus debated, due to different definitions and low quality trials.

The concept of video game disorder is itself being debated, with the overlap of its symptoms with other mental disorders, the unclear consensus on a definition and thresholds, and the lack of evidence raising doubts on whether or not this qualifies as a mental disorder of its own. Despite the lack of a unified definition, there is an emerging consensus among studies that Internet gaming disorder is mainly defined by three features: 1) withdrawal, 2) loss of control, and 3) conflict. Although the DSM-5 definition of video game disorder has a good fit to current methodological definitions used in trials and studies, there are still debates on the clinical pertinence.

Michael Brody, M.D., head of the TV and Media Committee of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, stated in a 2007 press release that "... there is not enough research on whether or not video games are addictive." However, Brody also cautioned that for some children and adolescents, "... it displaces physical activity and time spent on studies, with friends, and even with family."

A major issue concerns the lack of consistent measures and definitions and of acquisition of follow-up data. Furthermore, the study design quality has not greatly improved between the 2000s and 2017. For instance, most studies measured internet gaming behaviors in terms of frequency of use (total time spent), without considering the type of game (e.g., MMORPG), the social context (e.g., physically or virtually with friends), nor the motivations (e.g., competitive, achievement-oriented "grinding"). Although the amount of time spent was postulated by Johanssonn and Götestam in 2004 to lead to pathological behaviors, it is unclear whether the time spent is a cause or a consequence of pathological use. These criticisms, however, mostly pertain to Western research since there is more data of higher quality available in Asian regions, where the Internet gaming disorder is more prevalent.

A survey conducted in 2019 of 214 scholars shown that 60.8% agreed that pathological video game use could be a mental health problems, whereas 30.4% were skeptical. However, only 49.7% agreed with the DSM-5 definition of Internet gaming disorder, and 56.5% to the definition of the World Health Organization. Most scholars were worried that WHO's and DSM-5's inclusion of Internet gaming disorder was "overpathologizing normal youth" and "precipitated moral panic over video games". This indicates a lack of consensus on the issue as of 2019.

A study published in 2010 reviewed the findings of video game addiction by use of a motorcycle riding computer game with 17 users. 9 of the users were “abstinent ecstasy users” and the other 8 served as the control group. The 2 groups had their dopamine releases monitored throughout the test. After playing, the control group showed reduced dopamine D2 receptor occupancy of 10.5% in the caudate compared to former baseline levels. The abstinent group reported no changes in their dopamine receptors.

History

Video game addiction has been studied since the 1980s, and has seen a significant increase in the number of empirical studies since then.

The press has reported concerns over online gaming since at least 1994, when Wired mentioned a college student who was playing a MUD game for 12 hours a day instead of attending class.

Press reports have noted that some Finnish Defence Forces' conscripts were not mature enough to meet the demands of military life and were required to interrupt or postpone military service for a year. One reported source of the lack of needed social skills is overuse of computer games or the internet. Forbes termed this overuse "Web fixations" and stated they were responsible for 13 such interruptions or deferrals over the five years from 2000 to 2005.

In an April 2008 article, The Daily Telegraph reported that surveys of 391 players of Asheron's Call showed that three percent of respondents experienced agitation when they were unable to play, or missed sleep or meals to play. The article reports that University of Bolton lead researcher John Charlton said, "Our research supports the idea that people who are heavily involved in game playing may be nearer to autistic spectrum disorders than people who have no interest in gaming."

On 6 March 2009, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's (CBC) national news magazine program the fifth estate aired an hour-long report on video game addiction and the Brandon Crisp story, titled "Top Gun", subtitled "When a video gaming obsession turns to addiction and tragedy."

In August 2010, Wired reported that a man in Hawaii, Craig Smallwood, sued the gaming company NCSoft for negligence and for not specifying that their game, Lineage II, was so addictive. He alleged he would not have begun playing if he was aware he would become addicted. Smallwood says he has played Lineage for 20,000 hours between 2004 and 2009.

In 2013, a man from China observed his son's addiction to video games, and decided to take action. He hired online assassins to kill his son's virtual avatar every time he logged in. He hoped that being relentlessly killed would help his son lose interest in this destructive habit.

Inclusion in the ICD-11

In the draft versions leading to the final ICD-11 document, gaming disorder was included alongside gambling disorder under "Disorders Due to Addictive Behaviors". The addition defines as "a pattern of persistent or recurrent gaming behaviour ('digital gaming' or 'video-gaming')", defined by three criteria: the lack of control over playing video games, priority given to video games over other interests, and the inability to stop playing video games even after being affected by negative consequences. For gaming disorder to be diagnosed, the behavior pattern must be of sufficient severity to result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and would normally have been evident for at least 12 months. Research shows gaming disorders can be associated with anxiety, depression, loneliness, obesity, sleeping disorders, attention problems, and stress.

Vladimir Poznyak, the coordinator for the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, defended the addition of gaming disorder, believing the backlash against the addition to be a moral panic as they chose a very narrow definition that encompasses only the most extreme cases of gaming disorder. He said evaluating a disorder for inclusion is nominally done without any external feedback "to avoid interference from commercial and other entities which may have vested interest in the outcome of the process". Dr. Poznyak asserted that several medical professionals consulting on the ICD-11 did believe gaming disorder to be real, and by including it in the ICD-11, there can now be earnest efforts to define its causes and symptoms betters and methods to deal with it, and now include the video game industry within the conversation to help reduce the effects of video games on public health.

The addition of "gaming disorder" to the ICD-11 was criticized by gamers and the video game industry, while some researchers remained skeptical. Some of these researchers said the evidence remains weak and "there is a genuine risk of abuse of diagnoses." A group of 26 scholars wrote an open letter to the WHO, suggesting that the proposed diagnostic categories lacked scientific merit and were likely to do more harm than good. In counter-argument, a group of fifty academic researchers in behavioral science agreed that the evidence to support gaming disorder was weak, but it would be best that WHO identify gaming disorder in ICD-11 so that it could be considered a clinical and public health need.

A report, prepared by mental health experts at Oxford University, Johns Hopkins University, Stockholm University and the University of Sydney, sponsored by The Association for UK Interactive Entertainment argues that while there may be potential addiction associated with video gaming, it is premature to consider it a disorder without further study, given the stigmatisation that surrounds video, and ask the WHO to use caution when finalising the ICD draft. This report was promoted by 22 video game industry trade organizations including the Entertainment Software Association of the United States and Interactive Software Federation of Europe

As the final approval of the ICD-11 neared, several video game trade associations issued a statement requesting WHO to reconsider the addition of "gaming disorder", stating that, "The evidence for its inclusion remains highly contested and inconclusive". The Entertainment Software Association had meetings with the WHO during December 2018 to try to convince them to hold off including gaming disorder within ICD-11, with more planned meetings to follow.

Society and culture

Parental concerns

According to ABC News, parents have many concerns about their children playing video games, including concerns about age appropriateness, the amount of time spent playing games, physical health, and aggressive behaviour.

Governmental concerns

The first video game to attract political controversy was the 1978 arcade game Space Invaders. In 1981, a political bill called the Control of Space Invaders (and other Electronic Games) Bill was drafted by British Labour Party MP George Foulkes in an attempt to ban the game for its "addictive properties" and for causing "deviancy". The bill was debated and only narrowly defeated in parliament by 114 votes to 94 votes.

In August 2005, the government of the People's Republic of China, where more than 20 million people play online games, introduced an online gaming restriction limiting playing time to three hours, after which the player would be expelled from whichever game they were playing. In 2006, it relaxed the rule so only citizens under the age of 18 would face the limitation. Reports indicate underage gamers found ways to circumvent the measure. In July 2007, the rule was relaxed yet again. Internet games operating in China must require users identify themselves by resident identity numbers. After three hours, players under 18 are prompted to stop and "do suitable physical exercise". If they continue, their in-game points are "slashed in half". After five hours, all their points are automatically erased.

In 2008 in the United States (US), one of the five Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Commissioners, Deborah Taylor Tate, stated that online gaming addiction was "one of the top reasons for college drop-outs". However, she did not mention a source for the statement nor identify its position in relation to other top reasons.

In 2011, the South Korean government implemented a law, known as the Shutdown law or the Cinderella Law, which prohibits children under the age of 16 from playing online video games between the hours of 12:00 a.m. to 6:00 a.m. Later on, the law was amended and now children under the age of 16 can play after midnight if they have permission from their parents. In 2021, the South Korean government moved to abolish this law.

A systematic review identified in 2017 three types of currently attempted governmental policies: 1) limiting the availability of video games (shutdown, fatigue system, parental controls), 2) reduce the risks and harm (warning messages), 3) provide addiction help services to gamers. Most of these policies were either not as efficient as intended or not yet evaluated for efficiency, which lead some researchers to prompt for a global public health approach to prevent the onset and progression of this disorder. Some researchers suggest that the video game industry should itself place preventive measures against video game addiction.

Deaths

There have been at least a few deaths caused directly by exhaustion from playing games for excessive periods of time.

China

In 2005, thirteen-year-old Zhang Xiaoyi committed suicide by jumping from the top of a 24-story tower block in his home province Tianjin. After previously having spent two straight days playing online role-playing games in an Internet cafe, Zhang had told his parents that he had "been poisoned by games and could no longer control himself". His parents sued Aomeisoft, the China-region publisher of the game World of Warcraft. The head of a software association said to gaming website Play.tm that same year: "In the hypothetical world created by such games, [players] become confident and gain satisfaction, which they cannot get in the real world."

In 2007, a 26-year-old man identified only as "Zhang" died of a heart attack following a seven-day gaming binge, while a 30-year-old man died in a Guangzhou Internet cafe after playing online games for three straight days.

South Korea

In 2005, 28-year old industrial repairman Seungseob Lee (Hangul: 이승섭) visited an Internet cafe in the city of Daegu and played StarCraft almost continuously for fifty hours. He went into cardiac arrest and died at a local hospital. A friend reported: "... he was a game addict. We all knew about it. He couldn't stop himself." About six weeks before his death, he was fired from his job, and his girlfriend, also an avid gamer, broke up with him.

In 2009, Kim Sa-rang, a 3-month-old Korean girl, starved to death after both her parents spent hours each day in an Internet cafe, rearing a virtual child in an online game, Prius Online. The death is covered in the 2014 documentary Love Child.

United States

In November 2001, 21-year-old Wisconsinite Shawn Woolley committed suicide; it has been inferred that his death was related to the popular computer game EverQuest. Shawn's mother said the suicide was due to a rejection or betrayal in the game from a character Shawn called "iluvyou".

Ohio teenager Daniel Petric shot his parents, killing his mother, after they took away his copy of Halo 3 in October 2007. In a sentencing hearing after the teen was found guilty of aggravated murder, the judge said, "I firmly believe that Daniel Petric had no idea at the time he hatched this plot that if he killed his parents they would be dead forever", in reference to his disconnection from reality caused by playing violent video games. On 16 June 2009, Petric was sentenced to 23 years to life in prison.