Rosie the Riveter is an allegorical cultural icon in the United States who represents the women who worked in factories and shipyards during World War II, many of whom produced munitions and war supplies. These women sometimes took entirely new jobs replacing the male workers who joined the military. Rosie the Riveter is used as a symbol of American feminism and women's economic advantage.

Similar images of women war workers appeared in other countries such as Britain and Australia. The idea of Rosie the Riveter originated in a song written in 1942 by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. Images of women workers were widespread in the media in formats such as government posters, and commercial advertising was heavily used by the government to encourage women to volunteer for wartime service in factories. Rosie the Riveter became the subject and title of a Hollywood film in 1944.

History

Women in the wartime workforce

Because the world wars were total wars, which required governments to utilize their entire populations to defeat their enemies, millions of women were encouraged to work in the industry and take over jobs previously done by men. During World War I women across the United States were employed in jobs previously done by men. World War II was similar to World War I in that massive conscription of men led to a shortage of available workers and therefore a demand for labor which could be filled only by employing women.

Nearly 19 million women held jobs during World War II. Many of these women were already working in lower-paying jobs or were returning to the work-force after being laid off during the depression. Only three million new female workers entered the workforce during the time of the war.

Women responded to the call of need the country was displaying by stepping up to fill positions that were traditionally filled by men. They began to work heavy construction machinery, taking roles in lumber and steel mills as well as physical labor including unloading freight, building dirigibles (which are airships similar to air balloons), making munitions, and much more. Forty women were hired by Pan American Airways to replace men in the repair and maintenance department in the hangars at LaGuardia airfield for service, repair and overhaul on the fleet of aircraft including the Boeing 314 Flying Boat flying to and from Europe.

Many women discovered they enjoyed the autonomy these jobs provided them with. It expanded their own expectations for womanly duty and capabilities. Unfortunately, this was reckoned as unnatural and as men began to return home from the war, the government instituted another propaganda campaign urging women to "return to normalcy".

Although most women took on male-dominated trades during World War II, they were expected to return to their everyday housework once men returned from the war. Government campaigns targeting women were addressed solely at housewives, likely because already-employed women would move to the higher-paid "essential" jobs on their own, or perhaps because it was assumed that most would be housewives. One government advertisement asked women: "Can you use an electric mixer? If so, you can learn to operate a drill." Propaganda was also directed at their husbands, many of whom were unwilling to support such jobs.

Many of the women who took jobs during World War II were mothers. Those women with children at home pooled together in their efforts to raise their families. They assembled into groups and shared such chores as cooking, cleaning and washing clothes. Many who did have young children shared apartments and houses so they could save time, money, utilities and food. If they both worked, they worked different shifts so they could take turns babysitting. Taking on a job during World War II made people unsure if they should urge the women to keep acting as full-time mothers, or support them getting jobs to support the country in this time of need.

Being able to support the soldiers by making all sorts of different products made the women feel very accomplished and proud of their work. Over six million women got war jobs; African American, Hispanic, White, and Asian women worked side by side. In the book A Mouthful of Rivets, Vi Kirstine Vrooman writes about the time when she decided to take action and become a riveter. She got a job building B-17s on an assembly line, and shares just how exciting it was, saying, "The biggest thrill—I can't tell you—was when the B-17s rolled off the assembly line. You can't believe the feeling we had. We did it!" Once women accepted the challenge of the workforce they continued to make strong advances towards equal rights.

In 1944, when victory seemed assured for the Allied Forces, government-sponsored propaganda changed by urging women back to working in the home. Later, many women returned to traditional work such as clerical or administration positions, despite their reluctance to re-enter the lower-paying fields. However, some of these women continued working in the factories. The overall percentage of women working fell from 36% to 28% in 1947.

The song

| "Rosie the Riveter" | |

|---|---|

Cover of the published music to the 1942 song | |

| Song by Kay Kyser | |

| Published | 1942 |

| Songwriter(s) | Redd Evans, John Jacob Loeb |

The term "Rosie the Riveter" was first used in 1942 in a song of the same name written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. The song was recorded by numerous artists, including the popular big band leader Kay Kyser, and it became a national hit. It was also recorded by the R&B group, The Four Vagabonds. The song portrays "Rosie" as a tireless assembly line worker, who earned a "Production E" doing her part to help the American war effort.

The identity of the "real" Rosie the riveter is debated. Candidates include:

- Rosina "Rosie" Bonavita who worked for Convair in San Diego, California.

- Rosalind P. Walter, who "came from old money and worked on the night shift building the F4U Corsair fighter." Later in life Walter was a philanthropist, a board member of the WNET public television station in New York and an early and long-time supporter of the Charlie Rose interview show.

- Adeline Rose O'Malley, a riveter at Boeing's Wichita plant.

- Rose Will Monroe, a riveter at the Willow Run Aircraft Factory in Ypsilanti, Michigan, building B-24 bombers for the U.S. Army Air Forces. Born in Pulaski County, Kentucky, in 1920, she moved to Michigan during World War II. The song "Rosie the Riveter" was already popular when Monroe was selected to portray her in a promotional film about the war effort at home. "Rosie" went on to become perhaps the most widely recognized icon of that era. The films and posters she appeared in were used to encourage women to go to work in support of the war effort. At the age of 50, Monroe realized her dream of flying when she obtained a pilot's license. In 1978, she crashed in her small propeller plane when the engine failed during takeoff. The accident resulted in the loss of one kidney and the sight in her left eye, and ended her flying career. She died from kidney failure on May 31, 1997, in Clarksville, Indiana, at the age of 77.

In Canada in 1941, Veronica Foster became "Ronnie, the Bren Gun Girl", Canada's poster girl representing women in the war effort.

A drama film, Rosie the Riveter, was released in 1944, borrowing from the Rosie theme.

Impact

During the Second World War

According to the Encyclopedia of American Economic History, "Rosie the Riveter" inspired a social movement that increased the number of working American women from 12 million to 20 million by 1944, a 57% increase from 1940. By 1944 1.7 million unmarried men between the ages of 20 and 34 worked in the defense industry, while 4.1 million unmarried women between those ages did so.

Although the image of "Rosie the Riveter" reflected the industrial work of welders and riveters during World War II, the majority of working women filled non-factory positions in every sector of the economy. What unified the experiences of these women was that they proved to themselves (and the country) that they could do a "man's job" and could do it well.

In 1942, just between the months of January and July, the estimates of the proportion of jobs that would be "acceptable" for women was raised by employers from 29 to 85%. African American women were some of those most affected by the need for women workers. It has been said that it was the process of whites working alongside blacks during the time that encouraged a breaking down of social barriers and a healthy recognition of diversity.

Postwar

Women quickly responded to Rosie the Riveter, who convinced them that they had a patriotic duty to enter the workforce. Some claim that she forever opened the work force for women, but others dispute that point, noting that many women were discharged after the war and their jobs were given to returning servicemen. These critics claim that when peace returned, few women returned to their wartime positions and instead resumed domestic vocations or transferred into sex-typed occupations such as clerical and service work.

For some, World War II represented a major turning point for women as they eagerly supported the war effort, but other historians emphasize that the changes were temporary and that immediately after the war was over, women were expected to return to traditional roles of wives and mothers. A third group has emphasized how the long-range significance of the changes brought about by the war provided the foundation for the contemporary woman's movement. Leila J. Rupp, in her study of World War II, wrote "For the first time, the working woman dominated the public image. Women were riveting housewives in slacks, not mother, domestic beings, or civilizers."

After the war, as the nation shifted to a time of peace, women were quickly laid off from their factory jobs. The "Rosies" and the generations that followed them knew that working in the factories was in fact a possibility for women, even though they did not reenter the job market in such large proportions again until the 1970s. By that time factory employment was in decline all over the country.

Elinor Otto, known as "Last Rosie the Riveter", built airplanes for 50 years, retiring at age 95.

Homages

According to Penny Colman's Rosie the Riveter, there was also, very briefly, a "Wendy the Welder" based on Janet Doyle, a worker at the Kaiser Richmond Liberty Shipyards in California.

In the 1960s, Hollywood actress Jane Withers gained fame as "Josephine the Plumber", a character in a long-running and popular series of television commercials for "Comet" cleansing powder that lasted into the 1970s. This character was based on the original "Rosie" character.

One of Carnival Cruise Line's ships, the Carnival Valor, has a restaurant located on the lido deck named Rosie's Restaurant. The restaurant is mostly a tribute to Rosie, but also contains artwork depicting other war-related manufacturing and labor.

In 2010, singer Pink paid tribute to Rosie by dressing as her for a portion of the music video for the song "Raise Your Glass".

The 2013 picture book Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty, features Rosie as "Great Great Aunt Rose" who "Worked building aeroplanes a long time ago". She inspires Rosie Revere, the young subject of the book, to continue striving to be a great engineer despite early failures. Rose is shown wielding a walking stick made from riveted aircraft aluminum.

Singer Beyoncé paid tribute to Rosie in July 2014, dressing as the icon and posing in front of a "We Can Do It!" sign often mistaken as part of the Rosie campaign. It garnered over 1.15 million likes, but sparked minor controversy when newspaper The Guardian criticized it.

Other recent cultural references include a "Big Daddy" enemy type called "Rosie" in the video game BioShock, armed with a rivet gun. There is a DC Comics character called Rosie the Riveter, who wields a rivet gun as a weapon (first appearing in Green Lantern vol. 2 No. 176, May 1984). In the video game Fallout 3 there are billboards featuring "Rosies" assembling atom bombs while drinking Nuka-Cola. Of the female hairstyles available for player characters in the sequel, one is titled "Wendy the Welder" as a pastiche.

Boeing Orbital Flight Test 2, an uncrewed test flight of the Boeing Starliner spacecraft to the International Space Station, carried an Anthropomorphic Test Device named "Rosie the Rocketeer." The device contained fifteen sensors to collect data on the effects of the flight on future passengers.

Recognition

The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter by Connie Field is a 65-minute documentary from 1980 that tells the story of women's entrance into "men's work" during WWII. Rosies of the North is a 1999 National Film Board of Canada documentary film about Canadian "Rosies," who built fighter and bomber aircraft at the Canadian Car and Foundry, where Elsie MacGill was also the Chief Aeronautical Engineer.

John Crowley's 2009 historical novel Four Freedoms covers the wartime industries, and studies the real working conditions of many female industrial workers. "Rosie the Riveter" is frequently referenced.

On October 14, 2000, the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park was opened in Richmond, California, site of four Kaiser Shipyards, where thousands of "Rosies" from around the country worked (although ships at the Kaiser yards were not riveted, but rather welded). Over 200 former Rosies attended the ceremony.

In 2014, Phyllis Gould, one of the original Rosie the Riveters, visited President Barack Obama in support of a National Rosie the Riveter Day; the United States Senate approved the observance on March 21 in 2017. She also pushed for a Gold Medal for Rosies that will be given starting in 2022.

Also in 2014 a nationwide program, run by the organization Thanks! Plain and Simple, was founded to encourage cities to pick a project that "Rosies" can do with younger generations, in order to educate young people about women's roles in World War II, and to involve the "Rosies", many of whom have become isolated as they have gotten older, in community projects.

The name and logo of the Metropolitan Riveters, one of the founding members of the National Women's Hockey League, are inspired by the character of Rosie the Riveter.

The Rose City Riveters is the fan club for the Portland Thorns Football Club, a National Women's Soccer League team in Portland, Oregon, nicknamed the Rose City. They have taken their inspiration (and their name) from the 30,000 women who worked in the Portland shipyards in Portland during World War II.

Images

Westinghouse poster

In 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller was hired by the Westinghouse Company's War Production Coordinating Committee to create a series of posters for the war effort. One of these posters became the famous "We Can Do It!" image, an image that in later years would also be called "Rosie the Riveter" although it had never been given that title during the war. Miller is thought to have based his "We Can Do It!" poster on a United Press International wire service photograph taken of a young female war worker, widely but erroneously reported as being a photo of Michigan war worker Geraldine Hoff (later Doyle).

More recent evidence indicates that the formerly misidentified photo is actually of war worker Naomi Parker (later Fraley) taken at Alameda Naval Air Station in California. The "We Can Do It!" poster was displayed only to Westinghouse employees in the Midwest during a two-week period in February 1943, then it disappeared for nearly four decades. During the war, the name "Rosie" was not associated with the image, and the purpose of the poster was not to recruit women workers but to be motivational propaganda aimed at workers of both sexes already employed at Westinghouse. It was only later, in the early 1980s, that the Miller poster was rediscovered and became famous, associated with feminism, and often mistakenly called "Rosie the Riveter".

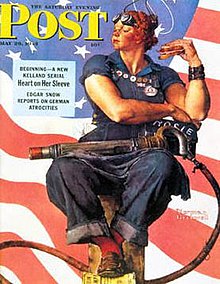

Saturday Evening Post

Norman Rockwell's image of "Rosie the Riveter" received mass distribution on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on Memorial Day, May 29, 1943. Rockwell's illustration features a brawny woman taking her lunch break with a rivet gun on her lap and beneath her penny loafer a copy of Adolf Hitler's manifesto, Mein Kampf. Her lunch box reads "Rosie"; viewers quickly recognized that to be "Rosie the Riveter" from the familiar song.

Rockwell, America's best-known popular illustrator of the day, based the pose of his 'Rosie' on that of Michelangelo's 1509 painting Prophet Isaiah from the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Rosie is holding a ham sandwich in her left hand, and her blue overalls are adorned with badges and buttons: a Red Cross blood donor button, a white "V for Victory" button, a Blue Star Mothers pin, an Army-Navy E Service production award pin, two bronze civilian service awards, and her personal identity badge.

Rockwell's model was a Vermont resident, 19-year-old Mary Louise Doyle, who was a telephone operator near where Rockwell lived, not a riveter. Rockwell painted his "Rosie" as a larger woman than his model, and he later phoned to apologize. According to two of Doyle's obituaries, however, "twenty-four years after Doyle posed, Rockwell sent Doyle a letter calling her the most beautiful woman he'd ever seen and apologizing for the hefty body in the painting. 'I did have to make you into a sort of a giant,' he wrote."

In a post interview, Mary explained that she was actually holding a sandwich while posing for the poster and that the rivet-gun she was holding was fake, she never saw Hitler's copy of Mein Kampf, and she did have a white handkerchief in her pocket like the picture depicts. The Post's cover image proved hugely popular, and the magazine loaned it to the United States Department of the Treasury for the duration of the war, for use in war bond drives.

After the war, the Rockwell "Rosie" was seen less and less because of a general policy of vigorous copyright protection by the Rockwell estate. In 2002, the original painting sold at Sotheby's for nearly $5 million. In June 2009 the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, acquired Norman Rockwell's iconic Rosie the Riveter painting for its permanent collection from a private collector.

In late 1942, Doyle posed twice for Rockwell's photographer, Gene Pelham, as Rockwell preferred to work from still images rather than live models. The first photo was not suitable, because she wore a blouse rather than a blue work shirt. In total, she was paid $10 for her modeling work (equivalent to $157 in 2021). In 1949 she married Robert J. Keefe to become Mary Doyle Keefe. The Keefes were invited and present in 2002 when the Rockwell painting was sold at Sotheby's.

In an interview in 2014, Keefe said that she had no idea what impact the painting would have. "I didn't expect anything like this, but as the years went on, I realized that the painting was famous," she said. Keefe died on April 21, 2015, in Connecticut at the age of 92.