From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

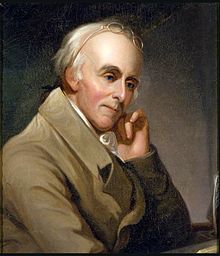

Benjamin Rush (January 4, 1746 [O.S. December 24, 1745] – April 19, 1813) was an American revolutionary, a Founding Father of the United States and signatory to the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educator, and the founder of Dickinson College. Rush was a Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress. He later described his efforts in support of the American Revolution, saying: "He aimed right." He served as surgeon general of the Continental Army and became a professor of chemistry, medical theory, and clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania.

Rush was a leader of the American Enlightenment and an enthusiastic supporter of the American Revolution. He was a leader in Pennsylvania's ratification of the U.S. Constitution

in 1788. He was prominent in many reforms, especially in the areas of

medicine and education. He opposed slavery, advocated free public

schools, and sought improved, but patriarchal,

education for women, and a more enlightened penal system. As a leading

physician, Rush had a major impact on the emerging medical profession.

As an Enlightenment intellectual, Rush was committed to organizing all medical knowledge around explanatory theories, rather than rely on empirical methods.

Rush argued that illness was the result of imbalances in the body's

physical system and was caused by malfunctions in the brain. His

approach prepared the way for later medical research, but Rush undertook

none of it. He promoted public health by advocating clean environment

and stressing the importance of personal and military hygiene. His study

of mental disorder made him one of the founders of American psychiatry. In 1965, the American Psychiatric Association recognized Rush as the "father of American psychiatry".

Early life and career

Coat of Arms of Benjamin Rush

Rush was born to John Rush and Susanna Hall on January 4, 1746 (December 24, 1745 O.S.). The family, of English descent, lived on a farm in the Township of Byberry in Philadelphia County,

about 14 miles outside of Philadelphia (the township was incorporated

into Philadelphia in 1854). Rush was the fourth of seven children. His

father died in July 1751 at age 39, leaving his mother, who ran a

country store, to care for the family. At age eight, Benjamin was sent

to live with an aunt and uncle to receive an education. He and his older brother Jacob attended a school run by Reverend Samuel Finley, which later became West Nottingham Academy.

In 1760, after further studies at the College of New Jersey, which in 1895 became Princeton University, Rush graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree at age 14. From 1761 to 1766, Rush apprenticed under Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia. Redman encouraged him to further his studies at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, where Rush studied from 1766 to 1768 and earned an M. D. degree. Rush became fluent in French, Italian, and Spanish as a result of his studies and European tour. While at Edinburgh, he became a friend of the Earl of Leven and his family, including William Leslie.

Returning to the Colonies in 1769, Rush opened a medical practice in Philadelphia and became professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia (which in 1791 changed its name to its present name, University of Pennsylvania). After his election to the revived American Philosophical Society

in 1768, Rush served as the society's curator from 1770 to 1773, as

secretary from 1773 to 1773, and vice president from 1797 to 1801. Rush ultimately published the first American textbook on chemistry and several volumes on medical student education and wrote influential patriotic essays.

Revolutionary period

Rush was active in the Sons of Liberty and was elected to attend the provincial conference to send delegates to the Continental Congress. Thomas Paine consulted Rush when writing the profoundly influential pro-independence pamphlet Common Sense. Starting in 1776, Rush represented Pennsylvania and signed the Declaration of Independence. He also represented Philadelphia at Pennsylvania's own Constitutional Convention.

In an 1811 letter to John Adams, Rush recounted in stark fashion

the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He described it as a

scene of "pensive and awful silence". Rush said the delegates were

called up, one after another, and then filed forward somberly to

subscribe to what each thought was their ensuing death warrant. He related that the "gloom of the morning" was briefly interrupted when the rotund Benjamin Harrison of Virginia said to a diminutive Elbridge Gerry

of Massachusetts, at the signing table, "I shall have a great advantage

over you, Mr. Gerry, when we are all hung for what we are now doing.

From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes and be

with the Angels, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in

the air an hour or two before you are dead."

According to Rush, Harrison's remark "procured a transient smile, but

it was soon succeeded by the Solemnity with which the whole business was

conducted."

While Rush was representing Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress

(and serving on its medical committee), he also used his medical skills

in the field. Rush accompanied the Philadelphia militia during the

battles after which the British occupied Philadelphia and most of New

Jersey. He was depicted serving in the Battle of Princeton in the painting The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777 by the American artist John Trumbull.

The Army Medical Service was in disarray, between the military casualties, extremely high losses from typhoid, yellow fever and other camp illnesses, political conflicts between Dr. John Morgan and Dr. William Shippen, Jr., and inadequate supplies and guidance from the medical committee. Nonetheless, Rush accepted an appointment as surgeon-general of the

middle department of the Continental Army. Rush's order "Directions for

preserving the health of soldiers" became one of the foundations of

preventive military medicine and was repeatedly republished, including

as late as 1908.

However, Rush's reporting of Shippen's misappropriation of food and

wine supplies intended to comfort hospitalized soldiers, under-reporting

of patient deaths, and failure to visit the hospitals under his

command, ultimately led to Rush's resignation in 1778.

Controversy

Rush criticized General George Washington in two handwritten but unsigned letters while still serving under the surgeon general. One, to Virginia Governor Patrick Henry dated October 12, 1778, quotes General Thomas Conway

saying that if not for God's grace the ongoing war would have been lost

by Washington and his weak counselors. Henry forwarded the letter to

Washington, despite Rush's request that the criticism be conveyed

orally, and Washington recognized the handwriting. At the time, the

supposed Conway Cabal was reportedly trying to replace Washington with Horatio Gates as commander-in-chief. Rush's letter relayed General John Sullivan's

criticism that forces directly under Washington were undisciplined and

mob-like, and contrasted Gates' army as "a well-regulated family". Ten days later, Rush wrote to John Adams

relaying complaints inside Washington's army, including about "bad

bread, no order, universal disgust" and praising Conway, who had been

appointed to inspector general.

Shippen sought Rush's resignation and received it by the end of the month after Continental Congress delegate John Witherspoon,

chairman of a committee to investigate Morgan's and Rush's charges of

misappropriation and mismanagement against Shippen, told Rush his

complaints would not produce reform.

Rush later expressed regret for his gossip against Washington. In a

letter to John Adams in 1812, Rush wrote, "He [Washington] was the

highly favored instrument whose patriotism and name contributed greatly

to the establishment of the independence of the United States." Rush

also successfully pleaded with Washington's biographers Justice Bushrod Washington and Chief Justice John Marshall to delete his association with those stinging words.

In his 2005 book 1776, David McCullough quotes Rush, referring to George Washington:

The

Philadelphia physician and patriot Benjamin Rush, a staunch admirer,

observed that Washington "has so much martial dignity in his deportment

that you would distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among

10,000 people. There is not a king in Europe that would not look like a

valet de chambre by his side."

Post-Revolution

Rush believed that, while America was free from British rule, the

"American Revolution" had yet to finish. As expressed in his 1787

'Address to the People of the United States', "The American war is

over: but this is far from being the case with the American

revolution. On the contrary, nothing but the first act of the great

drama is closed." In this address, he encouraged Americans to "come forward" and continue advancements on behalf of America.

In 1783, he was appointed to the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital,

and he remained a member until his death. He was elected to the

Pennsylvania convention which adopted the Federal constitution and was

appointed treasurer of the United States Mint, serving from 1797 to 1813. He was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1788.

He became a professor of medical theory and clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania in 1791, though the quality of his medicine was quite primitive even for the time: he advocated bloodletting

for almost any illness, long after its practice had declined. While

teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, one of his students was

future president William Henry Harrison, who took a chemistry class from Rush. He became a social activist and an abolitionist and was the most well-known physician in America at the time of his death.

He was also founder of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In 1794, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic,

Rush treated patients with bleeding, calomel, and other early medicinal

techniques that often were ineffective and actually brought many

patients closer to their deathbeds. Rush's ideas on yellow fever

treatments differed from those of many experienced French doctors, who

came from the West Indies where they had yellow fever outbreaks every year.

Rush was a founding member of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons (known today as the Pennsylvania Prison Society), which greatly influenced the construction of Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia. He supported Thomas Jefferson for president in 1796 over the eventual winner, John Adams.

Corps of Discovery

In 1803, Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia to prepare for the Lewis and Clark Expedition

under the tutelage of Rush, who taught Lewis about frontier illnesses

and the performance of bloodletting. Rush provided the corps with a

medical kit that included:

- Turkish opium for nervousness

- emetics to induce vomiting

- medicinal wine

- fifty dozen of Dr. Rush's Bilious Pills, laxatives containing more than 50% mercury,

which have since colloquially been referred to as "thunderclappers."

Their meat-rich diet and lack of clean water during the expedition gave

the men cause to use them frequently. Although their efficacy is

questionable, their high mercury content provided an excellent tracer by

which archaeologists have been able to track the corps' actual route to

the Pacific.

Reforms

Anti-slavery

In 1766, when Rush set out for his studies in Edinburgh, he was outraged by the sight of 100 slave ships in Liverpool

harbor. As a prominent Presbyterian doctor and professor of chemistry

in Philadelphia, he provided a bold and respected voice against the

slave trade. He warmly praised the ministry of "Black Harry" Hosier, the freedman circuit rider who accompanied Bishop Francis Asbury during the establishment of the Methodist Church in America,

but the highlight of his involvement was the pamphlet he wrote in 1773

entitled "An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in

America, upon Slave-Keeping." In this first of his many attacks on the

social evils of his day, he assailed the slave trade as well as the

entire institution of slavery. Rush argued scientifically that Negroes

were not by nature intellectually or morally inferior. Any apparent

evidence to the contrary was only the perverted expression of slavery,

which "is so foreign to the human mind, that the moral faculties, as

well as those of the understanding are debased, and rendered torpid by

it."

Anti-capital punishment

Rush deemed public punishments such as putting a person on display in stocks,

common at the time, to be counterproductive. Instead, he proposed

private confinement, labor, solitude, and religious instruction for

criminals, and he opposed the death penalty. His outspoken opposition to capital punishment pushed the Pennsylvania legislature to abolish the death penalty for all crimes other than first-degree murder. He authored a 1792 treatise on punishing murder by death in which he made three principal arguments:

- I. Every man possesses an absolute power over his own liberty and property, but not over his own life...

- II. The punishment of murder by death, is contrary to reason, and to the order and happiness of society...

- III. The punishment of murder by death, is contrary to divine revelation.

Rush led the state of Pennsylvania to establish the first state penitentiary, the Walnut Street Prison, in 1790. Rush campaigned for long-term imprisonment, the denial of liberty, as both the most humane but severe punishment.

This 1792 treatise was preceded by comments on the efficacy of the

death penalty that he self-references and which, evidently, appeared in

the second volume of the American Museum.

Status of women

After

the Revolution, Rush proposed a new model of education for elite women

that included English language, vocal music, dancing, sciences,

bookkeeping, history, and moral philosophy. He was instrumental to the

founding of the Young Ladies' Academy of Philadelphia, the first chartered women's institution of higher education in Philadelphia.

Rush saw little need for training women in metaphysics, logic,

mathematics, or advanced science; rather he wanted the emphasis on

guiding women toward moral essays, poetry, history, and religious

writings. This type of education for elite women grew dramatically

during the post-revolutionary period, as women claimed a role in

creating the Republic. And so, the ideal of Republican motherhood

emerged, lauding women's responsibility of instructing the young in the

obligations of patriotism, the blessings of liberty and the true

meaning of Republicanism. He opposed coeducational classrooms and insisted on the need to instruct all youth in the Christian religion.

Medical contributions

Physical medicine

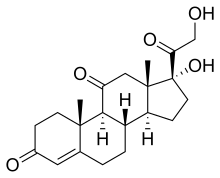

Rush was a leading proponent of heroic medicine. He firmly believed in such practices as bloodletting patients (a practice now known to be generally harmful, but at the time common practice), as well as purges using calomel

and other toxic substances. In his report on the Philadelphia yellow

fever epidemic of 1793, Rush wrote: "I have found bleeding to be useful,

not only in cases where the pulse was full and quick but where it was

slow and tense. I have bled twice in many and in one acute case four

times, with the happiest effect. I consider intrepidity in the use of

the lancet, at present, to be necessary, as it is in the use of mercury and jalap,

in this insidious and ferocious disease." During that epidemic, Rush

gained acclaim for remaining in town and treating sometimes 100 patients

per day (some through freed black volunteers coordinated by Richard Allen),

but many died. Even Rush acknowledged the failure of two treatments,

sweats in vinegar-wrapped blankets accompanied by mercury rubs, and cold

baths.

William Cobbett

vociferously objected to Rush's extreme use of bloodletting, and even

in Rush's day and location, many physicians had abandoned on scientific

grounds this favorite remedy of Rush's former teachers Thomas Sydenham and Hermann Boerhaave. Cobbett accused Rush of killing more patients than he had saved. Rush ultimately sued Cobbett for libel, winning a judgment of $5,000 and $3,000 in court costs, which was only partially paid before Cobbett returned to England. Nonetheless, Rush's practice waned as he continued to advocate

bloodletting and purges, much to the chagrin of his friend Thomas

Jefferson. Some even blamed Rush's bleeding for hastening the death of Benjamin Franklin,

as well as George Washington (although the only one of Washington's

medics who opposed the bleeding was Rush's former student), and Rush

insisted upon being bled himself shortly before his death (as he had

during the yellow fever epidemic two decades earlier).

Rush also wrote the first case report on dengue fever (published in 1789 on a case from 1780).

Perhaps his greatest contributions to physical medicine were his

establishment of a public dispensary for low-income patients

(Philadelphia Dispensary), and public works associated with draining and

rerouting Dock Creek (eliminating mosquito breeding grounds, which greatly decreased typhus, typhoid and cholera outbreaks).

Another of Rush's medical views that now draws criticism is his

analysis of race. In reviewing the case of Henry Moss, a slave who lost

his dark skin color (probably through vitiligo),

Rush characterized being black as a hereditary and curable skin

disease. Rush wrote that the "disease, instead of inviting us [whites]

to tyrannise over them [blacks], it should entitle them to a double

portion of our humanity." He added that this "should teach white people

the necessity of keeping up that prejudice against [miscegenation], as

it would tend to infect posterity with … their disorder" and called for

an "endeavour to discover a remedy for it."

Rush was interested in Native American health. He wanted to find

out why Native Americans were susceptible to certain illnesses and

whether they had higher mortality rates as compared to other people.

Other questions that he raised were whether they dreamed more and if

their hair turned gray as they got older. His fascination with these

people came from his interest in the theory that social scientists can

better study the history of their own civilization by studying cultures

in earlier stages of development, "primitive men". In his autobiography,

he writes "From a review of the three different species of settlers, it

appears that there are certain regular stages which mark the progress

from the savage to civilized life. The first settler is nearly related

to an Indian in his manners. In the second, the Indian manners are more

diluted. It is in the third species only that we behold civilization

completed. It is to the third species of settlers only that it is proper

to apply the term of farmers. While we record the voices of the first

and second settlers, it is but just to mention their virtues likewise.

Their mutual wants to produce mutual dependence; hence they are kind and

friendly to each other. Their solitary situation makes visitors

agreeable to them; hence they are hospitable to a stranger."

Mental health

"The Moral Thermometer" from Rush's

An Inquiry into the Effects of Spirituous Liquors on the Human Body and the Mind, published in 1790; its original edition is now housed in the

Library Company of PhiladelphiaRush published one of the first descriptions and treatments for psychiatric disorders in American medicine, Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind (1812).

He undertook to classify different forms of mental illness and to

theorize as to their causes and possible cures. Rush believed

(incorrectly) that many mental illnesses were caused by disruptions of

blood circulation or by sensory overload and treated them with devices

meant to improve circulation to the brain such as a centrifugal

spinning board, and inactivity/sensory deprivation via a restraining

chair with a sensory-deprivation head enclosure ("tranquilizer chair").

After seeing mental patients in appalling conditions in Pennsylvania

Hospital, Rush led a successful campaign in 1792 for the state to build a

separate mental ward where the patients could be kept in more humane

conditions.

Rush believed, as did so many physicians of the time, that

bleeding and active purging with mercury(I) chloride (calomel) were the

preferable medical treatments for insanity, a fact evidenced by his

statement that, "It is sometimes difficult to prevail upon patients in

this state of madness, or even to compel them, to take mercury in any of

the ways in which it is usually administered. In these cases I have

succeeded, by sprinkling a few grains of calomel daily upon a piece of

bread, and afterwards spreading over it, a thin covering of butter."

Rush followed the standard procedures of bleeding and treatment with

mercury, he did believe that "coercion" and "restraint", the physical

punishment, chains and dungeons, which were the practice of the time,

were the answer as proven by his invention of the restraint chair and

other devices. For this reason, some aspects of his approach could be

seen as similar to Moral Therapy, which would soon rise to prominence in at least the wealthier institutions of Europe and the United States.

Rush is sometimes considered a pioneer of occupational therapy particularly as it pertains to the institutionalized. In Diseases of the Mind (1812), Rush wrote:

It has been remarked that the

maniacs of the male sex in all hospitals, who assist in cutting wood,

making fires, and digging in a garden, and the females who are employed

in washing, ironing, and scrubbing floors, often recover, while persons,

whose rank exempts them from performing such services, languish away

their lives within the walls of the hospital.

Furthermore, Rush was one of the first people to describe Savant Syndrome. In 1789, he described the abilities of Thomas Fuller, an enslaved African who was a lightning calculator. His observation would later be described in other individuals by notable scientists like John Langdon Down.

Rush pioneered the therapeutic approach to addiction.

Prior to his work, drunkenness was viewed as being sinful and a matter

of choice. Rush believed that the alcoholic loses control over himself

and identified the properties of alcohol, rather than the alcoholic's

choice, as the causal agent. He developed the conception of alcoholism as a form of medical disease and proposed that alcoholics should be weaned from their addiction via less potent substances.

Rush advocated for more humane mental institutions and

perpetuated the idea that people with mental illness are people who have

an illness, rather than inhuman animals. He is quoted to have said,

"Terror acts powerfully upon the body, through the medium of the mind,

and should be employed in the cure of madness." He also championed the idea of "partial madness," or that people could have varying degrees of mental illness.

The American Psychiatric Association's seal bears an image of Rush's purported profile at its center. The outer ring of the seal contains the words "American Psychiatric Association 1844". The Association's history of the seal states:

The choice of Rush (1746–1813) for

the seal reflects his place in history. .... Rush's practice of

psychiatry was based on bleeding, purging, and the use of the

tranquilizer chair and gyrator. By 1844 these practices were considered

erroneous and abandoned. Rush, however, was the first American to study

mental disorder in a systematic manner, and he is considered the father

of American Psychiatry.

Educational legacy

During his career, he educated over 3,000 medical students, and several of these established Rush Medical College in Chicago in his honor after his death. His students included Valentine Seaman, who mapped yellow fever mortality patterns in New York and introduced the smallpox vaccine to the United States in 1799. One of his last apprentices was Samuel A. Cartwright, later a Confederate States of America surgeon charged with improving sanitary conditions in the camps around Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Louisiana. Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, formerly Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center, was named in his honor.

Religious views and vision

Rush advocated Christianity in public life and in education and sometimes compared himself to the prophet Jeremiah. Rush regularly attended Christ Church in Philadelphia and counted William White

among his closest friends (and neighbors). Ever the controversialist,

Rush became involved in internal disputes over the revised Book of Common Prayer and the splitting of the Episcopal Church from the Church of England. He dabbled with Presbyterianism, Methodism (which split from Anglicanism in those years), and Unitarianism. In a letter to John Adams, Rush describes his religious views as "a compound of the orthodoxy and heterodoxy of most of our Christian churches." Christian Universalists consider him one of their founders, although Rush stopped attending that church after the death of his friend, former Baptist pastor Elhanan Winchester, in 1797.

Rush fought for temperance and both public and Sunday schools. He helped found the Bible Society at Philadelphia (now known as the Pennsylvania Bible Society) and promoted the American Sunday School Union.

When many public schools stopped using the Bible as a textbook, Rush

proposed that the U.S. government require such use, as well as furnish

an American Bible to every family at public expense. In 1806, Rush

proposed inscribing "The Son of Man Came into the World, Not To Destroy

Men's Lives, But To Save Them."

above the doors of courthouses and other public buildings. Earlier, on

July 16, 1776, Rush had complained to Patrick Henry about a provision in

Virginia's constitution of 1776 which forbade clergymen from serving in the legislature.

Rush felt that the United States was the work of God: "I do not

believe that the Constitution was the offspring of inspiration, but I am

as perfectly satisfied that the Union of the United States in its form

and adoption is as much the work of a Divine Providence as any of the

miracles recorded in the Old and New Testament".

In 1798, after the Constitution's adoption, Rush declared: "The only

foundation for a useful education in a republic is to be laid in

Religion. Without this there can be no virtue, and without virtue there

can be no liberty, and liberty is the object and life of all republican

governments."

One quote popularly assigned to Rush, however, which portrays him as a

medical libertarian: "Unless we put medical freedoms into the

Constitution, the time will come when medicine will organize into an

undercover dictatorship [. . .] To restrict the art of healing to one

class of men and deny equal privileges to others will constitute the

Bastille of medical science. All such laws are un-American and despotic

and have no place in a republic [. . .] The Constitution of this

republic should make special privilege for medical freedom as well as

religious freedom," is likely a misattribution. No primary source for it

has been found, and the words "un-American" and "undercover" are

anachronisms, as their usage as such did not appear until after Rush's

death.

Before 1779, Rush's religious views were influenced by what he described as "Fletcher's controversy with the Calvinists

in favor of the Universality of the atonement." After hearing Elhanan

Winchester preach, Rush indicated that this theology "embraced and

reconciled my ancient calvinistical, and my newly adopted (Arminian) principles. From that time on I have never doubted upon the subject of the salvation of all men." To simplify, both believed in punishment after death for the wicked. His wife, Julia Rush, thought her husband like Martin Luther for his ardent passions, fearless attacks on old prejudices, and quick tongue against perceived enemies.

Rush helped Richard Allen found the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In his autobiography, Allen wrote:

...By this time we had waited on

Dr. Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston, and told them of our distressing

situation. We considered it a blessing that the Lord had put it into our

hearts to wait upon... those gentle-men. They pitied our situation, and

subscribed largely towards the church, and were very friendly towards

us and advised us how to go on.

We appointed Mr. Ralston our treasurer. Dr. Rush did much for us in

public by his influence. I hope the name of Dr. Benjamin Rush and Mr.

Robert Ralston will never be forgotten among us. They were the two first

gentlemen who espoused the cause of the oppressed and aided us in

building the house of the Lord for the poor Africans to worship in. Here

was the beginning and rise of the first African church in America."

Personal life

On January 11, 1776, Rush married Julia Stockton (1759–1848), daughter of Richard Stockton, another signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his wife Annis Boudinot Stockton. They had 13 children, 9 of whom survived their first year: John, Ann Emily, Richard,

Susannah (died as an infant), Elizabeth Graeme (died as an infant),

Mary B, James, William (died as an infant), Benjamin (died as an

infant), Richard, Julia, Samuel, and William. Richard later became a member of the cabinets of James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor (at one point during each of their presidencies).

In 1812, Rush helped reconcile the friendship of Jefferson and Adams by encouraging the two former presidents to resume writing to each other.

Once divided over politics and political rivalries, Jefferson and Adams

grew close. On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the

U.S. Declaration of Independence, Jefferson and Adams both died within hours of each other.

Death

After dying of typhus fever, he was buried (in Section N67) along with his wife Julia in the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, not far from where Benjamin Franklin is buried.

At the site, a small plaque honoring Benjamin Rush has been placed.

However, the box marker is next to the plaque on the right, with

inscriptions on the top. The inscription reads,

In memory of

Benjamin Rush MD

he died on the 19th of April

in the year of our Lord 1813

Aged 68 years

Well done good and faithful servant

enter thou into the joy of the Lord

Mrs Julia Rush

consort of

Benjamin Rush MD

Born March 2, 1759

Died July 7, 1848

For as in Adam, all die, even so in Christ

Shall all be made alive

Legacy

Benjamin Rush Elementary School in Redmond, Washington was named by its students for him. The Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush magnet high school in Philadelphia was established in 2008. Rush County, Indiana, is named for him as is its county seat, Rushville. Rush University Medical Center in Chicago is named after Rush. Benjamin Rush State Park in Philadelphia is named after Rush. The eponymous conservative Benjamin Rush Institute is an associate member of the State Policy Network.

Controversy regarding quotations

George Seldes includes in his widely recognized 1960 book The Great Quotations a quote by Rush:

"The

Constitution of this Republic should make special provision for medical

freedom. To restrict the art of healing to one class will constitute

the Bastille of medical science."

The book includes a detailed depiction of sources and methodologies used by Seldes to gather the quotes. However Thomas Szasz

in recent years has claimed to believe this is a false attribution,

while avoiding to mention Seldes' book: "...Not a single author supplies

a verifiable source for it. Hence, I believe this false attribution,

depicting Rush as a medical libertarian, needs to be exposed as bogus."

Writings

- Rush, Benjamin (1819) [1791]. An

inquiry into the effects of ardent spirits upon the human body and

mind : with an account of the means of preventing, and of the remedies

for curing them. Josiah Richardson.

- Rush, Benjamin (1794). An account of the bilious remitting yellow fever, as it appeared in the city of Philadelphia, in the year 1793. Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson.

- Rush, Benjamin (1798). Essays: Literary, Moral, and Philosophical. Philadelphia: Thomas & Samuel F. Bradford. 1989 reprint: Syracuse University Press, ISBN 0-912756-22-5

- Rush, Benjamin (1799). "Observations

Intended to Favour a Supposition That the Black Color (As It Is Called)

of the Negroes Is Derived from the Leprosy". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 4: 289–297. doi:10.2307/1005108. JSTOR 1005108.

- Rush, Benjamin, M.D. (1806). A plan of a Peace-Office for the United States. Essays, Literary, Moral and Philosophical. (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Thomas and William Bradford. pp. 183–88. Retrieved June 3, 2010 – via Internet Archive.

- Rush, Benjamin (1808) [1778]. Directions for preserving the health of soldiers : addressed to the officers of the Army of the United States. Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson.

- Rush, Benjamin (1812) Medical Inquiries And Observations Upon The Diseases Of The Mind, 2006 reprint: Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-4286-2669-7. Free digital copies of original published in 1812 at http://deila.dickinson.edu/theirownwords/title/0034. or https://web.archive.org/web/20121024024628/http://collections.nlm.nih.gov/muradora/objectView.action?pid=nlm%3Anlmuid-2569036R-bk

- Rush, Benjamin (2003). "Medical

Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind:

Philadelphia: Published by Kimber & Richardson, no. 237, Market

Street; Merritt, printer, no. 9, Watkins Alley, 1812". Their Own Words. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Dickinson College. OCLC 53177922. Archived from the original on January 7, 2004. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- Rush, Benjamin (1815). "A Defence of Blood-letting, as a Remedy for Certain Diseases". Medical Inquiries and Observations. 4. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- Rush, Benjamin (1830). Medical Inquiries and Observations upon Diseases of the Mind (4 ed.). Philadelphia: John Grigg. pp. 98, 197.

- Rush, Benjamin (1835). Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon the Diseases of the Mind (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia: Grigg and Elliott, No. 9 North Fourth Street. OCLC 2812179. Retrieved October 20, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Rush, Benjamin (1947). The selected writings of Benjamin Rush. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-8065-2955-4.

- Butterfield, Lyman H., ed. (1951). Letters of Benjamin Rush. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. Princeton University Press. OCLC 877738348.

- The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush, 1805–1813 (2001), Liberty Fund, ISBN 0-86597-287-7

- Rush, Benjamin (1970) [1948]. George Washington Corner (ed.). The autobiography of Benjamin Rush; his Travels through life together with his Commonplace book for 1789–1813. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Fox, Claire G.; Miller, Gordon L.; Miller, Jacquelyn C. (1996). Benjamin Rush, M.D: A Bibliographic Guide. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29823-3.

Archival collections

The

Presbyterian Historical Society in

Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, has a collection of

Benjamin Rush's original manuscripts.