Numeracy is the ability to understand, reason with, and to apply simple numerical concepts. The charity National Numeracy states: "Numeracy means understanding how mathematics is used in the real world and being able to apply it to make the best possible decisions...It’s as much about thinking and reasoning as about 'doing sums'". Basic numeracy skills consist of comprehending fundamental arithmetical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. For example, if one can understand simple mathematical equations such as 2 + 2 = 4, then one would be considered to possess at least basic numeric knowledge. Substantial aspects of numeracy also include number sense, operation sense, computation, measurement, geometry, probability and statistics. A numerically literate person can manage and respond to the mathematical demands of life.

By contrast, innumeracy (the lack of numeracy) can have a negative impact. Numeracy has an influence on healthy behaviors, financial literacy, and career decisions. Therefore, innumeracy may negatively affect economic choices, financial outcomes, health outcomes, and life satisfaction. It also may distort risk perception in health decisions. Greater numeracy has been associated with reduced susceptibility to framing effects, less influence of nonnumerical information such as mood states, and greater sensitivity to different levels of numerical risk. Ellen Peters and her colleagues argue that achieving the benefits of numeric literacy, however, may depend on one's numeric self-efficacy or confidence in one's skills.

Representation of numbers

Humans have evolved to mentally represent numbers in two major ways from observation (not formal math). These representations are often thought to be innate (see Numerical cognition), to be shared across human cultures, to be common to multiple species, and not to be the result of individual learning or cultural transmission. They are:

- Approximate representation of numerical magnitude, and

- Precise representation of the quantity of individual items.

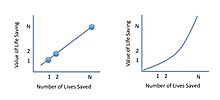

Approximate representations of numerical magnitude imply that one can relatively estimate and comprehend an amount if the number is large (see Approximate number system). For example, one experiment showed children and adults arrays of many dots. After briefly observing them, both groups could accurately estimate the approximate number of dots. However, distinguishing differences between large numbers of dots proved to be more challenging.

Precise representations of distinct items demonstrate that people are more accurate in estimating amounts and distinguishing differences when the numbers are relatively small (see Subitizing). For example, in one experiment, an experimenter presented an infant with two piles of crackers, one with two crackers the other with three. The experimenter then covered each pile with a cup. When allowed to choose a cup, the infant always chose the cup with more crackers because the infant could distinguish the difference.

Both systems—approximate representation of magnitude and precise representation quantity of individual items—have limited power. For example, neither allows representations of fractions or negative numbers. More complex representations require education. However, achievement in school mathematics correlates with an individual's unlearned approximate number sense.

Definitions and assessment

Fundamental (or rudimentary) numeracy skills include understanding of the real number line, time, measurement, and estimation. Fundamental skills include basic skills (the ability to identify and understand numbers) and computational skills (the ability to perform simple arithmetical operations and compare numerical magnitudes).

More sophisticated numeracy skills include understanding of ratio concepts (notably fractions, proportions, percentages, and probabilities), and knowing when and how to perform multistep operations. Two categories of skills are included at the higher levels: the analytical skills (the ability to understand numerical information, such as required to interpret graphs and charts) and the statistical skills (the ability to apply higher probabilistic and statistical computation, such as conditional probabilities).

A variety of tests have been developed for assessing numeracy and health numeracy. Different tests have been developed to evaluate health numeracy. Two of these tests that have been found to be “reliable and valid” are the GHNT-21 and GHNT-6.

Childhood influences

The first couple of years of childhood are considered to be a vital part of life for the development of numeracy and literacy. There are many components that play key roles in the development of numeracy at a young age, such as Socioeconomic Status (SES), parenting, Home Learning Environment (HLE), and age.

Socioeconomic status

Children who are brought up in families with high SES tend to be more engaged in developmentally enhancing activities. These children are more likely to develop the necessary abilities to learn and to become more motivated to learn. More specifically, a mother's education level is considered to have an effect on the child's ability to achieve in numeracy. That is, mothers with a high level of education will tend to have children who succeed more in numeracy.

A number of studies have, moreover, proved that the education level of the mother is strongly correlated with the average age of getting married. More precisely, females who entered the marriage later, tend to have greater autonomy, chances for skills premium and level of education (i.e. numeracy). Hence, they were more likely to share this experience with children.

Parenting

Parents are advised to collaborate with their child in simple learning exercises, such as reading a book, painting, drawing, and playing with numbers. On a more expressive note, the act of using complex language, being more responsive towards the child, and establishing warm interactions are recommended to parents with the confirmation of positive numeracy outcomes. When discussing beneficial parenting behaviors, a feedback loop is formed because pleased parents are more willing to interact with their child, which in essence promotes better development in the child.

Home-learning environment

Along with parenting and SES, a strong home-learning environment increases the likelihood of the child being prepared for comprehending complex mathematical schooling. For example, if a child is influenced by many learning activities in the household, such as puzzles, coloring books, mazes, or books with picture riddles, then they will be more prepared to face school activities.

Age

Age is accounted for when discussing the development of numeracy in children. Children under the age of 5 have the best opportunity to absorb basic numeracy skills. After the age of seven, achievement of basic numeracy skills become less influential. For example, a study was conducted to compare the reading and mathematical abilities between children of ages five and seven, each in three different mental capacity groups (underachieving, average, and overachieving). The differences in the amount of knowledge retained were greater between the three different groups aged five than between the groups aged seven. This reveals that those of younger ages have an opportunity to retain more information, like numeracy. According to Gelman and Gallistel in The Child’s Understanding of Number, ‘children as young as 2 years can accurately judge numerosity provided that the numerosity is not larger than two or three’. Children as young as three have been found to understand elementary mathematical concepts. Kilpatrick and his colleagues state ‘most preschoolers show that they can understand and perform simple addition and subtraction by at least 3 years of age’. Lastly, it has been observed that pre-school children benefit from their basic understanding of ‘counting, reading and writing of numbers, understanding of simple addition and subtraction, numerical reasoning, classifying of objects and shapes, estimating, measuring, [and the] reproduction of number patterns’.

Literacy

There seems to be a relationship between literacy and numeracy, which can be seen in young children. Depending on the level of literacy or numeracy at a young age, one can predict the growth of literacy and/ or numeracy skills in future development. There is some evidence that humans may have an inborn sense of number. In one study for example, five-month-old infants were shown two dolls, which were then hidden with a screen. The babies saw the experimenter pull one doll from behind the screen. Without the child's knowledge, a second experimenter could remove, or add dolls, unseen behind the screen. When the screen was removed, the infants showed more surprise at an unexpected number (for example, if there were still two dolls). Some researchers have concluded that the babies were able to count, although others doubt this and claim the infants noticed surface area rather than number.

Employment

Numeracy has a huge impact on employment. In a work environment, numeracy can be a controlling factor affecting career achievements and failures. Many professions require individuals to have well-developed numerical skills: for example, mathematician, physicist, accountant, actuary, Risk Analyst, financial analyst, engineer, and architect. This is why a major target of the Sustainable Development Goal 4 is to substantially increase the number of youths who have relevant skills for decent work and employment because, even outside these specialized areas, the lack of numeracy skills can reduce employment opportunities and promotions, resulting in unskilled manual careers, low-paying jobs, and even unemployment. For example, carpenters and interior designers need to be able to measure, use fractions, and handle budgets. Another example of numeracy influencing employment was demonstrated at the Poynter Institute. The Poynter Institute has recently included numeracy as one of the skills required by competent journalists. Max Frankel, former executive editor of The New York Times, argues that "deploying numbers skillfully is as important to communication as deploying verbs". Unfortunately, it is evident that journalists often show poor numeracy skills. In a study by the Society of Professional Journalists, 58% of job applicants interviewed by broadcast news directors lacked an adequate understanding of statistical materials.

To assess job applicants, psychometric numerical reasoning tests have been created by occupational psychologists, who are involved in the study of numeracy. These tests are used to assess ability to comprehend and apply numbers. They are sometimes administered with a time limit, so that the test-taker must think quickly and concisely. Research has shown that these tests are very useful in evaluating potential applicants because they do not allow the applicants to prepare for the test, unlike interview questions. This suggests that an applicant's results are reliable and accurate.

These tests first became prevalent during the 1980s, following the pioneering work of psychologists, such as P. Kline, who published a book in 1986 entitled A handbook of test construction: Introduction to psychometric design, which explained that psychometric testing could provide reliable and objective results, which could be used to assess a candidate's numerical abilities.

Innumeracy and dyscalculia

The term innumeracy is a neologism, coined by analogy with illiteracy. Innumeracy refers to a lack of ability to reason with numbers. The term was coined by cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter; however, it was popularized in 1989 by mathematician John Allen Paulos in his book Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and its Consequences.

Developmental dyscalculia refers to a persistent and specific impairment of basic numerical-arithmetical skills learning in the context of normal intelligence.

Patterns and differences

The root causes of innumeracy vary. Innumeracy has been seen in those suffering from poor education and childhood deprivation of numeracy. Innumeracy is apparent in children during the transition between numerical skills obtained before schooling and the new skills taught in the education departments because of their memory capacity to comprehend the material. Patterns of innumeracy have also been observed depending on age, gender, and race. Older adults have been associated with lower numeracy skills than younger adults. Men have been identified to have higher numeracy skills than women. Some studies seem to indicate young people of African heritage tend to have lower numeracy skills. The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) in which children at fourth-grade (average 10 to 11 years) and eighth-grade (average 14 to 15 years) from 49 countries were tested on mathematical comprehension. The assessment included tests for number, algebra (also called patterns and relationships at fourth grade), measurement, geometry, and data. The latest study, in 2003, found that children from Singapore at both grade levels had the highest performance. Countries like Hong Kong SAR, Japan, and Taiwan also shared high levels of numeracy. The lowest scores were found in countries like South Africa, Ghana, and Saudi Arabia. Another finding showed a noticeable difference between boys and girls, with some exceptions. For example, girls performed significantly better in Singapore, and boys performed significantly better in the United States.

Theory

There is a theory that innumeracy is more common than illiteracy when dividing cognitive abilities into two separate categories. David C. Geary, a notable cognitive developmental and evolutionary psychologist from the University of Missouri, created the terms "biological primary abilities" and "biological secondary abilities". Biological primary abilities evolve over time and are necessary for survival. Such abilities include speaking a common language or knowledge of simple mathematics. Biological secondary abilities are attained through personal experiences and cultural customs, such as reading or high level mathematics learned through schooling. Literacy and numeracy are similar in the sense that they are both important skills used in life. However, they differ in the sorts of mental demands each makes. Literacy consists of acquiring vocabulary and grammatical sophistication, which seem to be more closely related to memorization, whereas numeracy involves manipulating concepts, such as in calculus or geometry, and builds from basic numeracy skills. This could be a potential explanation of the challenge of being numerate.

Innumeracy and risk perception in health decision-making

Health numeracy has been defined as "the degree to which individuals have the capacity to access, process, interpret, communicate, and act on numerical, quantitative, graphical, biostatistical, and probabilistic health information needed to make effective health decisions". The concept of health numeracy is a component of the concept of health literacy. Health numeracy and health literacy can be thought of as the combination of skills needed for understanding risk and making good choices in health-related behavior.

Health numeracy requires basic numeracy but also more advanced analytical and statistical skills. For instance, health numeracy also requires the ability to understand probabilities or relative frequencies in various numerical and graphical formats, and to engage in Bayesian inference, while avoiding errors sometimes associated with Bayesian reasoning (see Base rate fallacy, Conservatism (Bayesian)). Health numeracy also requires understanding terms with definitions that are specific to the medical context. For instance, although 'survival' and 'mortality' are complementary in common usage, these terms are not complementary in medicine (see five-year survival rate). Innumeracy is also a very common problem when dealing with risk perception in health-related behavior; it is associated with patients, physicians, journalists and policymakers. Those who lack or have limited health numeracy skills run the risk of making poor health-related decisions because of an inaccurate perception of information. For example, if a patient has been diagnosed with breast cancer, being innumerate may hinder her ability to comprehend her physician's recommendations, or even the severity of the health concern or even the likelihood of treatment benefits. One study found that people tended to overestimate their chances of survival or even to choose lower-quality hospitals. Innumeracy also makes it difficult or impossible for some patients to read medical graphs correctly. Some authors have distinguished graph literacy from numeracy. Indeed, many doctors exhibit innumeracy when attempting to explain a graph or statistics to a patient. A misunderstanding between a doctor and patient, due to either the doctor, patient, or both being unable to comprehend numbers effectively, could result in serious harm to health.

Different presentation formats of numerical information, for instance natural frequency icon arrays, have been evaluated to assist both low-numeracy and high-numeracy individuals. Other data formats provide more assistance to low-numeracy people.

Evolution of numeracy

In the field of economic history, numeracy is often used to assess human capital at times when there was no data on schooling or other educational measures. Using a method called age-heaping, researchers like Professor Jörg Baten study the development and inequalities of numeracy over time and throughout regions. For example, Baten and Hippe find a numeracy gap between regions in western and central Europe and the rest of Europe for the period 1790–1880. At the same time, their data analysis reveals that these differences as well as within country inequality decreased over time. Taking a similar approach, Baten and Fourie find overall high levels of numeracy for people in the Cape Colony (late 17th to early 19th century).

In contrast to these studies comparing numeracy over countries or regions, it is also possible to analyze numeracy within countries. For example, Baten, Crayen and Voth look at the effects of war on numeracy in England, and Baten and Priwitzer find a "military bias" in what is today western Hungary: people opting for a military career had - on average - better numeracy indicators (1 BCE to 3CE).