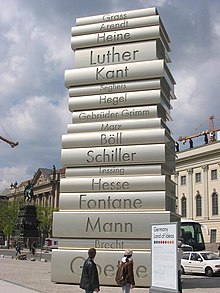

| Literature |

|---|

|

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature, much of which has been transcribed. Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.

Literature, as an art form, can also include works in various non-fiction genres, such as biography, diaries, memoir, letters, and essays. Within its broad definition, literature includes non-fictional books, articles or other printed information on a particular subject.

Etymologically, the term derives from Latin literatura/litteratura "learning, a writing, grammar," originally "writing formed with letters," from litera/littera "letter". In spite of this, the term has also been applied to spoken or sung texts. Literature is often referred to synecdochically as "writing", especially creative writing, and poetically as "the craft of writing" (or simply "the craft"). Syd Field described his discipline, screenwriting, as "a craft that occasionally rises to the level of art."

Developments in print technology have allowed an ever-growing distribution and proliferation of written works, which now include electronic literature.

Definitions

Definitions of literature have varied over time. In Western Europe, prior to the 18th century, literature denoted all books and writing. Literature can be seen as returning to older, more inclusive notions, so that cultural studies, for instance, include, in addition to canonical works, popular and minority genres. The word is also used in reference to non-written works: to "oral literature" and "the literature of preliterate culture".

A value judgment definition of literature considers it as consisting solely of high quality writing that forms part of the belles-lettres ("fine writing") tradition. An example of this is in the 1910–1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, which classified literature as "the best expression of the best thought reduced to writing".

History

Oral literature

The use of the term "literature" here is a little problematic because of its origins in the Latin littera, “letter,” essentially writing. Alternatives such as "oral forms" and "oral genres" have been suggested but the word literature is widely used.

Australian Aboriginal culture has thrived on oral traditions and oral histories passed down through tens of thousands of years. In a study published in February 2020, new evidence showed that both Budj Bim and Tower Hill volcanoes erupted between 34,000 and 40,000 years ago. Significantly, this is a "minimum age constraint for human presence in Victoria", and also could be interpreted as evidence for the oral histories of the Gunditjmara people, an Aboriginal Australian people of south-western Victoria, which tell of volcanic eruptions being some of the oldest oral traditions in existence. An axe found underneath volcanic ash in 1947 had already proven that humans inhabited the region before the eruption of Tower Hill.

Oral literature is an ancient human tradition found in "all corners of the world". Modern archaeology has been unveiling evidence of the human efforts to preserve and transmit arts and knowledge that depended completely or partially on an oral tradition, across various cultures:

The Judeo-Christian Bible reveals its oral traditional roots; medieval European manuscripts are penned by performing scribes; geometric vases from archaic Greece mirror Homer's oral style. (...) Indeed, if these final decades of the millennium have taught us anything, it must be that oral tradition never was the other we accused it of being; it never was the primitive, preliminary technology of communication we thought it to be. Rather, if the whole truth is told, oral tradition stands out as the single most dominant communicative technology of our species as both a historical fact and, in many areas still, a contemporary reality.

The earliest poetry is believed to have been recited or sung, employed as a way of remembering history, genealogy, and law.

In Asia, the transmission of folklore, mythologies as well as scriptures in ancient India, in different Indian religions, was by oral tradition, preserved with precision with the help of elaborate mnemonic techniques.

The early Buddhist texts are also generally believed to be of oral tradition, with the first by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek, Serbia and other cultures, then noting that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without being written down. According to Goody, the Vedic texts likely involved both a written and oral tradition, calling it a "parallel products of a literate society".

All ancient Greek literature was to some degree oral in nature, and the earliest literature was completely so. Homer's epic poetry, states Michael Gagarin, was largely composed, performed and transmitted orally. As folklores and legends were performed in front of distant audiences, the singers would substitute the names in the stories with local characters or rulers to give the stories a local flavor and thus connect with the audience, but making the historicity embedded in the oral tradition as unreliable. The lack of surviving texts about the Greek and Roman religious traditions have led scholars to presume that these were ritualistic and transmitted as oral traditions, but some scholars disagree that the complex rituals in the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations were an exclusive product of an oral tradition.

Writing systems are not known to have existed among Native North Americans before contact with Europeans. Oral storytelling traditions flourished in a context without the use of writing to record and preserve history, scientific knowledge, and social practices. While some stories were told for amusement and leisure, most functioned as practical lessons from tribal experience applied to immediate moral, social, psychological, and environmental issues. Stories fuse fictional, supernatural, or otherwise exaggerated characters and circumstances with real emotions and morals as a means of teaching. Plots often reflect real life situations and may be aimed at particular people known by the story's audience. In this way, social pressure could be exerted without directly causing embarrassment or social exclusion. For example, rather than yelling, Inuit parents might deter their children from wandering too close to the water's edge by telling a story about a sea monster with a pouch for children within its reach.

See also African literature#Oral literature

Oratory

Oratory or the art of public speaking "was for long considered a literary art". From Ancient Greece to the late 19th century, rhetoric played a central role in Western education in training orators, lawyers, counselors, historians, statesmen, and poets.

Writing

Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form. Though in both ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica, writing may have already emerged because of the need to record historical and environmental events. Subsequent innovations included more uniform, predictable, legal systems, sacred texts, and the origins of modern practices of scientific inquiry and knowledge-consolidation, all largely reliant on portable and easily reproducible forms of writing.

Early written literature

Ancient Egyptian literature, along with Sumerian literature, are considered the world's oldest literatures. The primary genres of the literature of ancient Egypt—didactic texts, hymns and prayers, and tales—were written almost entirely in verse; By the Old Kingdom (26th century BC to 22nd century BC), literary works included funerary texts, epistles and letters, hymns and poems, and commemorative autobiographical texts recounting the careers of prominent administrative officials. It was not until the early Middle Kingdom (21st century BC to 17th century BC) that a narrative Egyptian literature was created.

Many works of early periods, even in narrative form, had a covert moral or didactic purpose, such as the Sanskrit Panchatantra.200 BC – 300 AD, based on older oral tradition. Drama and satire also developed as urban culture provided a larger public audience, and later readership, for literary production. Lyric poetry (as opposed to epic poetry) was often the speciality of courts and aristocratic circles, particularly in East Asia where songs were collected by the Chinese aristocracy as poems, the most notable being the Shijing or Book of Songs (1046–c.600 BC).

In ancient China, early literature was primarily focused on philosophy, historiography, military science, agriculture, and poetry. China, the origin of modern paper making and woodblock printing, produced the world's first print cultures. Much of Chinese literature originates with the Hundred Schools of Thought period that occurred during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (769‒269 BC). The most important of these include the Classics of Confucianism, of Daoism, of Mohism, of Legalism, as well as works of military science (e.g. Sun Tzu's The Art of War, c.5th century BC) and Chinese history (e.g. Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, c.94 BC). Ancient Chinese literature had a heavy emphasis on historiography, with often very detailed court records. An exemplary piece of narrative history of ancient China was the Zuo Zhuan, which was compiled no later than 389 BC, and attributed to the blind 5th-century BC historian Zuo Qiuming.

In ancient India, literature originated from stories that were originally orally transmitted. Early genres included drama, fables, sutras and epic poetry. Sanskrit literature begins with the Vedas, dating back to 1500–1000 BC, and continues with the Sanskrit Epics of Iron Age India. The Vedas are among the oldest sacred texts. The Samhitas (vedic collections) date to roughly 1500–1000 BC, and the "circum-Vedic" texts, as well as the redaction of the Samhitas, date to c. 1000‒500 BC, resulting in a Vedic period, spanning the mid-2nd to mid 1st millennium BC, or the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The period between approximately the 6th to 1st centuries BC saw the composition and redaction of the two most influential Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, with subsequent redaction progressing down to the 4th century AD. Other major literary works are Ramcharitmanas & Krishnacharitmanas.

The earliest known Greek writings are Mycenaean (c.1600–1100 BC), written in the Linear B syllabary on clay tablets. These documents contain prosaic records largely concerned with trade (lists, inventories, receipts, etc.); no real literature has been discovered. Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, the original decipherers of Linear B, state that literature almost certainly existed in Mycenaean Greece, but it was either not written down or, if it was, it was on parchment or wooden tablets, which did not survive the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces in the twelfth century BC. Homer's epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are central works of ancient Greek literature. It is generally accepted that the poems were composed at some point around the late eighth or early seventh century BC. Modern scholars consider these accounts legendary. Most researchers believe that the poems were originally transmitted orally. From antiquity until the present day, the influence of Homeric epic on Western civilization has been great, inspiring many of its most famous works of literature, music, art and film. The Homeric epics were the greatest influence on ancient Greek culture and education; to Plato, Homer was simply the one who "has taught Greece" – ten Hellada pepaideuken. Hesiod's Works and Days (c.700 BC) and Theogony are some of the earliest, and most influential, of ancient Greek literature. Classical Greek genres included philosophy, poetry, historiography, comedies and dramas. Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) and Aristotle (384–322 BC) authored philosophical texts that are the foundation of Western philosophy, Sappho (c. 630 – c. 570 BC) and Pindar were influential lyric poets, and Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC) and Thucydides were early Greek historians. Although drama was popular in ancient Greece, of the hundreds of tragedies written and performed during the classical age, only a limited number of plays by three authors still exist: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The plays of Aristophanes (c. 446 – c. 386 BC) provide the only real examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy, the earliest form of Greek Comedy, and are in fact used to define the genre.

The Hebrew religious text, the Torah, is widely seen as a product of the Persian period (539–333 BC, probably 450–350 BC). This consensus echoes a traditional Jewish view which gives Ezra, the leader of the Jewish community on its return from Babylon, a pivotal role in its promulgation. This represents a major source of Christianity's Bible, which has had a major influence on Western literature.

The beginning of Roman literature dates to 240 BC, when a Roman audience saw a Latin version of a Greek play. Literature in Latin would flourish for the next six centuries, and includes essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings.

The Qur'an (610 AD to 632 AD), the main holy book of Islam, had a significant influence on the Arab language, and marked the beginning of Islamic literature. Muslims believe it was transcribed in the Arabic dialect of the Quraysh, the tribe of Muhammad. As Islam spread, the Quran had the effect of unifying and standardizing Arabic.

Theological works in Latin were the dominant form of literature in Europe typically found in libraries during the Middle Ages. Western Vernacular literature includes the Poetic Edda and the sagas, or heroic epics, of Iceland, the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, and the German Song of Hildebrandt. A later form of medieval fiction was the romance, an adventurous and sometimes magical narrative with strong popular appeal.

Controversial, religious, political and instructional literature proliferated during the European Renaissance as a result of the Johannes Gutenberg's invention of the printing press around 1440, while the Medieval romance developed into the novel,

Publishing

Publishing became possible with the invention of writing but became more practical with the invention of printing. Prior to printing, distributed works were copied manually, by scribes.

The Chinese inventor Bi Sheng made movable type of earthenware c.1045. In c.1450, Johannes Gutenberg independently invented movable type in Europe. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce and more widely available.

Early printed books, single sheets, and images created before 1501 in Europe are known as incunables or incunabula. "A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330."

Eventually, printing enabled other forms of publishing besides books. The history of newspaper publishing began in Germany in 1609, with the publishing of magazines following in 1663.

University discipline

In England

In England in the late 1820s, growing political and social awareness, "particularly among the utilitarians and Benthamites, promoted the possibility of including courses in English literary study in the newly formed London University". This further developed into the idea of the study of literature being "the ideal carrier for the propagation of the humanist cultural myth of a well educated, culturally harmonious nation".

America

Women and literature

The widespread education of women was not common until the nineteenth century, and because of this literature until recently was mostly male dominated.

George Sand was an idea. She has a unique place in our age.

Others are great men ... she was a great woman.

Victor Hugo, Les funérailles de George Sand

There were few English-language women poets whose names are remembered until the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century some names that stand out are Emily Brontë, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Emily Dickinson (see American poetry). But while generally women are absent from the European cannon of Romantic literature, there is one notable exception, the French novelist and memoirist Amantine Dupin (1804 – 1876) best known by her pen name George Sand. One of the more popular writers in Europe in her lifetime, being more renowned than both Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac in England in the 1830s and 1840s, Sand is recognised as one of the most notable writers of the European Romantic era. Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) is the first major English woman novelist, while Aphra Behn is an early female dramatist.

Nobel Prizes in Literature have been awarded between 1901 and 2020 to 117 individuals: 101 men and 16 women. Selma Lagerlöf (1858 – 1940) was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, which she was awarded in 1909. Additionally, she was the first woman to be granted a membership in The Swedish Academy in 1914.

Feminist scholars have since the twentieth century sought expand the literary canon to include more women writers.

Children's literature

A separate genre of children's literature only began to emerge in the eighteenth century, with the development of the concept of childhood. The earliest of these books were educational books, books on conduct, and simple ABCs—often decorated with animals, plants, and anthropomorphic letters.

Aesthetics

Literary theory

A fundamental question of literary theory is "what is literature?" – although many contemporary theorists and literary scholars believe either that "literature" cannot be defined or that it can refer to any use of language.

Literary fiction

Literary fiction is a term used to describe fiction that explores any facet of the human condition, and may involve social commentary. It is often regarded as having more artistic merit than genre fiction, especially the most commercially oriented types, but this has been contested in recent years, with the serious study of genre fiction within universities.

The following, by the award-winning British author William Boyd on the short story, might be applied to all prose fiction:

[short stories] seem to answer something very deep in our nature as if, for the duration of its telling, something special has been created, some essence of our experience extrapolated, some temporary sense has been made of our common, turbulent journey towards the grave and oblivion.

The very best in literature is annually recognized by the Nobel Prize in Literature, which is awarded to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, produced "in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction" (original Swedish: den som inom litteraturen har producerat det mest framstående verket i en idealisk riktning).

The value of imaginative literature

Some researchers suggest that literary fiction can play a role in an individual's psychological development. Psychologists have also been using literature as a therapeutic tool. Psychologist Hogan argues for the value of the time and emotion that a person devotes to understanding a character's situation in literature; that it can unite a large community by provoking universal emotions, as well as allowing readers access to different cultures, and new emotional experiences. One study, for example, suggested that the presence of familiar cultural values in literary texts played an important impact on the performance of minority students.

Psychologist Maslow's ideas help literary critics understand how characters in literature reflect their personal culture and the history. The theory suggests that literature helps an individual's struggle for self-fulfillment.

The influence of religious texts

Religion has had a major influence on literature, through works like the Vedas, the Torah, the Bible, and the Qur'an.

The King James Version of the Bible has been called "the most influential version of the most influential book in the world, in what is now its most influential language", "the most important book in English religion and culture", and "the most celebrated book in the English-speaking world" - principally because of its literary style and widespread distribution. Prominent atheist figures such as the late Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins have praised the King James Version as being "a giant step in the maturing of English literature" and "a great work of literature", respectively, with Dawkins then adding, "A native speaker of English who has never read a word of the King James Bible is verging on the barbarian".

Societies in which preaching has great importance, and those in which religious structures and authorities have a near-monopoly of reading and writing and/or a censorship role, may impart a religious gloss to much of the literature those societies produce or retain - as for example in the European Middle Ages. The traditions of close study of religious texts has furthered the development of techniques and theories in literary studies.

Types

Poetry

Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its greater use of the aesthetic qualities of language, including musical devices such as assonance, alliteration, rhyme, and rhythm, and by being set in lines and verses rather than paragraphs, and more recently its use of other typographical elements. This distinction is complicated by various hybrid forms such as sound poetry, concrete poetry and prose poem, and more generally by the fact that prose possesses rhythm. Abram Lipsky refers to it as an "open secret" that "prose is not distinguished from poetry by lack of rhythm".

Prior to the 19th century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines: "any kind of subject consisting of Rhythm or Verses". Possibly as a result of Aristotle's influence (his Poetics), "poetry" before the 19th century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art. As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition; hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

Prose

As noted above, prose generally makes far less use of the aesthetic qualities of language than poetry. However, developments in modern literature, including free verse and prose poetry have tended to blur the differences, and American poet T.S. Eliot suggested that while: "the distinction between verse and prose is clear, the distinction between poetry and prose is obscure". There are verse novels, a type of narrative poetry in which a novel-length narrative is told through the medium of poetry rather than prose. Eugene Onegin (1831) by Alexander Pushkin is the most famous example.

On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that "[In the case of ancient Greece] recent scholarship has emphasized the fact that formal prose was a comparatively late development, an "invention" properly associated with the classical period".

Latin was a major influence on the development of prose in many European countries. Especially important was the great Roman orator Cicero. It was the lingua franca among literate Europeans until quite recent times, and the great works of Descartes (1596 – 1650), Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626), and Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677) were published in Latin. Among the last important books written primarily in Latin prose were the works of Swedenborg (d. 1772), Linnaeus (d. 1778), Euler (d. 1783), Gauss (d. 1855), and Isaac Newton (d. 1727).

Novel

A novel is a long fictional prose narrative. In English, the term emerged from the Romance languages in the late 15th century, with the meaning of "news"; it came to indicate something new, without a distinction between fact or fiction. The romance is a closely related long prose narrative. Walter Scott defined it as "a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvelous and uncommon incidents", whereas in the novel "the events are accommodated to the ordinary train of human events and the modern state of society". Other European languages do not distinguish between romance and novel: "a novel is le roman, der Roman, il romanzo", indicates the proximity of the forms.

Although there are many historical prototypes, so-called "novels before the novel", the modern novel form emerges late in cultural history—roughly during the eighteenth century. Initially subject to much criticism, the novel has acquired a dominant position amongst literary forms, both popularly and critically.

Novella

The publisher Melville House classifies the novella as "too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story". Publishers and literary award societies typically consider a novella to be between 17,000 and 40,000 words.

Short story

A dilemma in defining the "short story" as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative and its contested origin, that include the Bible, and Edgar Allan Poe.

Graphic novel

Graphic novels and comic books present stories told in a combination of artwork, dialogue, and text.

Electronic literature

Electronic literature is a literary genre consisting of works created exclusively on and for digital devices.

Nonfiction

Common literary examples of nonfiction include, the essay; travel literature and nature writing; biography, autobiography and memoir; journalism; letters; journals; history, philosophy, economics; scientific, and technical writings.

Nonfiction can fall within the broad category of literature as "any collection of written work", but some works fall within the narrower definition "by virtue of the excellence of their writing, their originality and their general aesthetic and artistic merits".

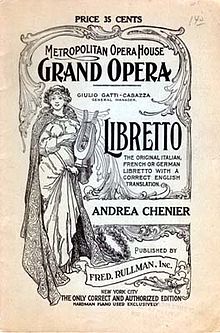

Drama

Drama is literature intended for performance. The form is combined with music and dance in opera and musical theatre (see libretto). A play is a written dramatic work by a playwright that is intended for performance in a theatre; it comprises chiefly dialogue between characters. A closet drama, by contrast, is written to be read rather than to be performed; the meaning of which can be realized fully on the page. Nearly all drama took verse form until comparatively recently.

The earliest form of which there exists substantial knowledge is Greek drama. This developed as a performance associated with religious and civic festivals, typically enacting or developing upon well-known historical, or mythological themes,

In the twentieth century scripts written for non-stage media have been added to this form, including radio, television and film.

Law

Law and literature

The law and literature movement focuses on the interdisciplinary connection between law and literature.

Copyright

Copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to make copies of a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, educational, or musical form. Copyright is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself.

United Kingdom

Literary works have been protected by copyright law from unauthorized reproduction since at least 1710. Literary works are defined by copyright law to mean "any work, other than a dramatic or musical work, which is written, spoken or sung, and accordingly includes (a) a table or compilation (other than a database), (b) a computer program, (c) preparatory design material for a computer program, and (d) a database."

Literary works are all works of literature; that is all works expressed in print or writing (other than dramatic or musical works).

United States

The copyright law of the United States has a long and complicated history, dating back to colonial times. It was established as federal law with the Copyright Act of 1790. This act was updated many times, including a major revision in 1976.

European Union

The copyright law of the European Union is the copyright law applicable within the European Union. Copyright law is largely harmonized in the Union, although country to country differences exist. The body of law was implemented in the EU through a number of directives, which the member states need to enact into their national law. The main copyright directives are the Copyright Term Directive, the Information Society Directive and the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. Copyright in the Union is furthermore dependent on international conventions to which the European Union is a member (such as the TRIPS Agreement and conventions to which all Member States are parties (such as the Berne Convention)).

Copyright in communist countries

Copyright in Japan

Japan was a party to the original Berne convention in 1899, so its copyright law is in sync with most international regulations. The convention protected copyrighted works for 50 years after the author's death (or 50 years after publication for unknown authors and corporations). However, in 2004 Japan extended the copyright term to 70 years for cinematographic works. At the end of 2018, as a result of the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, the 70 year term was applied to all works. This new term is not applied retroactively; works that had entered the public domain between 1999 and 2018 by expiration would remain in the public domain.

Censorship

Censorship of literature is employed by states, religious organizations, educational institutions, etc., to control what can be portrayed, spoken, performed, or written. Generally such bodies attempt to ban works for political reasons, or because they deal with other controversial matters such as race, or sex.

A notorious example of censorship is James Joyce's novel Ulysses, which has been described by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov as a "divine work of art" and the greatest masterpiece of 20th century prose. It was banned in the United States from 1921 until 1933 on the grounds of obscenity. Nowadays it is a central literary text in English literature courses, throughout the world.

Awards

There are numerous awards recognizing achievement and contribution in literature. Given the diversity of the field, awards are typically limited in scope, usually on: form, genre, language, nationality and output (e.g. for first-time writers or debut novels).

The Nobel Prize in Literature was one of the six Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, and is awarded to an author on the basis of their body of work, rather than to, or for, a particular work itself. Other literary prizes for which all nationalities are eligible include: the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Man Booker International Prize, Pulitzer Prize, Hugo Award, Guardian First Book Award and the Franz Kafka Prize.