| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress |

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension will continue to result, in an improved human condition; the latter may happen as a result of direct human action, as in social enterprise or through activism, or as a natural part of sociocultural evolution.

The concept of progress was introduced in the early-19th-century social theories, especially social evolution as described by Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. It was present in the Enlightenment's philosophies of history. As a goal, social progress has been advocated by varying realms of political ideologies with different theories on how it is to be achieved.

Measuring progress

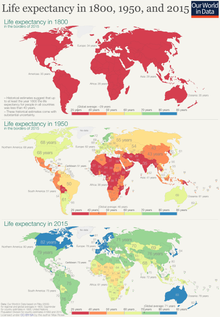

Specific indicators for measuring progress can range from economic data, technical innovations, change in the political or legal system, and questions bearing on individual life chances, such as life expectancy and risk of disease and disability.

GDP growth has become a key orientation for politics and is often taken as a key figure to evaluate a politician's performance. However, GDP has a number of flaws that make it a bad measure of progress, especially for developed countries. For example, environmental damage is not taken into account nor is the sustainability of economic activity. Wikiprogress has been set up to share information on evaluating societal progress. It aims to facilitate the exchange of ideas, initiatives and knowledge. HumanProgress.org is another online resource that seeks to compile data on different measures of societal progress.

Our World in Data is a scientific online publication, based at the University of Oxford, that studies how to make progress against large global problems such as poverty, disease, hunger, climate change, war, existential risks, and inequality. The mission of Our World in Data is to present "research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems".

The Social Progress Index is a tool developed by the International Organization Imperative Social Progress, which measures the extent to which countries cover social and environmental needs of its citizenry. There are fifty-two indicators in three areas or dimensions: Basic Human Needs, and Foundations of Wellbeing and Opportunities which show the relative performance of nations.

Indices that can be used to measure progress include:

- Broad measures of economic progress

- Disability-adjusted life year

- Green national product

- Gender-related Development Index

- Genuine Progress Indicator

- Gross National Happiness

- Gross National Well-being

- Happy Planet Index

- Human Development Index

- Legatum Prosperity Index

- Social Progress Index

- OECD Better Life Index

- Subjective life satisfaction

- Where-to-be-born Index

- Wikiprogress

- World Happiness Report

- World Values Survey

Scientific progress

Scientific progress is the idea that the scientific community learns more over time, which causes a body of scientific knowledge to accumulate. The chemists in the 19th century knew less about chemistry than the chemists in the 20th century, and they in turn knew less than the chemists in the 21st century. Looking forward, today's chemists reasonably expect that chemists in future centuries will know more than they do.

From the 18th century through late 20th century, the history of science, especially of the physical and biological sciences, was often presented as a progressive accumulation of knowledge, in which true theories replaced false beliefs. Some more recent historical interpretations, such as those of Thomas Kuhn, tend to portray the history of science in terms of competing paradigms or conceptual systems in a wider matrix of intellectual, cultural, economic and political trends. These interpretations, however, have met with opposition for they also portray the history of science as an incoherent system of incommensurable paradigms, not leading to any scientific progress, but only to the illusion of progress.

Whether other intellectual disciplines make progress in the same way as the sciences is a matter of debate. For example, one might expect that today's historians know more about global history than their ancient counterparts (consider the histories of Herodotus). Yet, knowledge can be lost through the passage of time, or the criteria for evaluating what is worth knowing can change. Similarly, there is considerable disagreement over whether fields such as philosophy make progress - or even whether they aim at accumulating knowledge in the same way as the sciences.

Social progress

Aspects of social progress, as described by Condorcet, have included the disappearance of slavery, the rise of literacy, the lessening of inequalities between the sexes, reforms of harsh prisons and the decline of poverty. The social progress of a society can be measured based on factors such as its ability to address fundamental human needs, help citizens improve their quality of life, and provide opportunities for citizens to succeed.

Social progress is often improved by increases in GDP, although other factors are also relevant. An imbalance between economic and social progress hinders further economic progress, and can lead to political instability. Where there is an imbalance between economic growth and social progress, political instability and unrest often arise. Lagging social progress also holds back economic growth in these and other countries that fail to address human needs, build social capital, and create opportunity for their citizens.

Status of women

How progress improved the status of women in traditional society was a major theme of historians starting in the Enlightenment and continuing to today. British theorists William Robertson (1721–1793) and Edmund Burke (1729–1797), along with many of their contemporaries, remained committed to Christian- and republican-based conceptions of virtue, while working within a new Enlightenment paradigm. The political agenda related beauty, taste, and morality to the imperatives and needs of modern societies of a high level of sophistication and differentiation. Two themes in the work of Robertson and Burke—the nature of women in 'savage' and 'civilized' societies and 'beauty in distress'—reveals how long-held convictions about the character of women, especially with regard to their capacity and right to appear in the public domain, were modified and adjusted to the idea of progress and became central to modern European civilization.

Classics experts have examined the status of women in the ancient world, concluding that in the Roman Empire, with its superior social organization, internal peace, and rule of law, allowed women to enjoy a somewhat better standing than in ancient Greece, where women were distinctly inferior. The inferior status of women in traditional China has raised the issue of whether the idea of progress requires a thoroughgoing rejection of traditionalism—a belief held by many Chinese reformers in the early 20th century.

Historians Leo Marx and Bruce Mazlish asking, "should we in fact abandon the idea of progress as a view of the past," answer that there is no doubt "that the status of women has improved markedly" in cultures that have adopted the Enlightenment idea of progress.

Modernization

Modernization was promoted by classical liberals in the 19th and 20th centuries, who called for the rapid modernization of the economy and society to remove the traditional hindrances to free markets and free movements of people. During the Enlightenment in Europe social commentators and philosophers began to realize that people themselves could change society and change their way of life. Instead of being made completely by gods, there was increasing room for the idea that people themselves made their own society—and not only that, as Giambattista Vico argued, because people made their own society, they could also fully comprehend it. This gave rise to new sciences, or proto-sciences, which claimed to provide new scientific knowledge about what society was like, and how one may change it for the better.

In turn, this gave rise to progressive opinion, in contrast with conservational opinion. The social conservationists were skeptical about panaceas for social ills. According to conservatives, attempts to radically remake society normally make things worse. Edmund Burke was the leading exponent of this, although later-day liberals like Hayek have espoused similar views. They argue that society changes organically and naturally, and that grand plans for the remaking of society, like the French Revolution, National Socialism and Communism hurt society by removing the traditional constraints on the exercise of power.

The scientific advances of the 16th and 17th centuries provided a basis for Francis Bacon's book the New Atlantis. In the 17th century, Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle described progress with respect to arts and the sciences, saying that each age has the advantage of not having to rediscover what was accomplished in preceding ages. The epistemology of John Locke provided further support and was popularized by the Encyclopedists Diderot, Holbach, and Condorcet. Locke had a powerful influence on the American Founding Fathers. The first complete statement of progress is that of Turgot, in his "A Philosophical Review of the Successive Advances of the Human Mind" (1750). For Turgot, progress covers not only the arts and sciences but, on their base, the whole of culture—manner, mores, institutions, legal codes, economy, and society. Condorcet predicted the disappearance of slavery, the rise of literacy, the lessening of inequalities between the sexes, reforms of harsh prisons and the decline of poverty.

John Stuart Mill's (1806–1873) ethical and political thought demonstrated faith in the power of ideas and of intellectual education for improving human nature or behavior. For those who do not share this faith the idea of progress becomes questionable.

Alfred Marshall (1842–1924), a British economist of the early 20th century, was a proponent of classical liberalism. In his highly influential Principles of Economics (1890), he was deeply interested in human progress and in what is now called sustainable development. For Marshall, the importance of wealth lay in its ability to promote the physical, mental, and moral health of the general population. After World War II, the modernization and development programs undertaken in the Third World were typically based on the idea of progress.

In Russia the notion of progress was first imported from the West by Peter the Great (1672–1725). An absolute ruler, he used the concept to modernize Russia and to legitimize his monarchy (unlike its usage in Western Europe, where it was primarily associated with political opposition). By the early 19th century, the notion of progress was being taken up by Russian intellectuals and was no longer accepted as legitimate by the tsars. Four schools of thought on progress emerged in 19th-century Russia: conservative (reactionary), religious, liberal, and socialist—the latter winning out in the form of Bolshevist materialism.[24]

The intellectual leaders of the American Revolution, such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, were immersed in Enlightenment thought and believed the idea of progress meant that they could reorganize the political system to the benefit of the human condition; both for Americans and also, as Jefferson put it, for an "Empire of Liberty" that would benefit all mankind. In particular, Adams wrote “I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.”

Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810–1884) was one of the most influential political theorists in Argentina. Economic liberalism was the key to his idea of progress. He promoted faith in progress, while chiding fellow Latin Americans for blind copying of American and European models. He hoped for progress through promotion of immigration, education, and a moderate type of federalism and republicanism that might serve as a transition in Argentina to true democracy.

In Mexico, José María Luis Mora (1794–1850) was a leader of classical liberalism in the first generation after independence, leading the battle against the conservative trinity of the army, the church, and the hacendados. He envisioned progress as both a process of human development by the search for philosophical truth and as the introduction of an era of material prosperity by technological advancement. His plan for Mexican reform demanded a republican government bolstered by widespread popular education free of clerical control, confiscation and sale of ecclesiastical lands as a means of redistributing income and clearing government debts, and effective control of a reduced military force by the government. Mora also demanded the establishment of legal equality between native Mexicans and foreign residents. His program, untried in his lifetime, became the key element in the Mexican Constitution of 1857.

In Italy, the idea that progress in science and technology would lead to solutions for human ills was connected to the nationalism that united the country in 1860. The Piedmontese Prime Minister Camillo Cavour envisaged the railways as a major factor in the modernization and unification of the Italian peninsula. The new Kingdom of Italy, formed in 1861, worked to speed up the processes of modernization and industrialization that had begun in the north, but were slow to arrive in the Papal States and central Italy, and were nowhere in sight in the "Mezzogiorno" (that is, Southern Italy, Sicily, and Sardinia). The government sought to combat the backwardness of the poorer regions in the south and work towards augmenting the size and quality of the newly created Italian army so that it could compete on an equal footing with the powerful nations of Europe. In the same period, the government was legislating in favour of public education to fight the great problem of illiteracy, upgrade the teaching classes, improve existing schools, and procure the funds needed for social hygiene and care of the body as factors in the physical and moral regeneration of the race.

In China, in the 20th century the Kuomintang or Nationalist party, which ruled from the 1920s to the 1940s, advocated progress. The Communists under Mao Zedong adopted western models and their ruinous projects caused mass famines. After Mao's death, however, the new regime led by Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997) and his successors aggressively promoted modernization of the economy using capitalist models and imported western technology. This was termed the "Opening of China" in the west, and more broadly encompasses Chinese economic reform.

Among environmentalists, there is a continuum between two opposing poles. The one pole is optimistic, progressive, and business-oriented, and endorses the classic idea of progress. For example, bright green environmentalism endorses the idea that new designs, social innovations and green technologies can solve critical environmental challenges. The other is pessimistic in respect of technological solutions, warning of impending global crisis (through climate change or peak oil, for example) and tends to reject the very idea of modernity and the myth of progress that is so central to modernization thinking. Similarly, Kirkpatrick Sale, wrote about progress as a myth benefiting the few, and a pending environmental doomsday for everyone. An example is the philosophy of Deep Ecology.

Philosophy

Sociologist Robert Nisbet said that "No single idea has been more important than ... the Idea of Progress in Western civilization for three thousand years", and defines five "crucial premises" of the idea of progress:

- value of the past

- nobility of Western civilization

- worth of economic/technological growth

- faith in reason and scientific/scholarly knowledge obtained through reason

- intrinsic importance and worth of life on earth

Sociologist P. A. Sorokin said, "The ancient Chinese, Babylonian, Hindu, Greek, Roman, and most of the medieval thinkers supporting theories of rhythmical, cyclical or trendless movements of social processes were much nearer to reality than the present proponents of the linear view". Unlike Confucianism and to a certain extent Taoism, that both search for an ideal past, the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition believes in the fulfillment of history, which was translated into the idea of progress in the modern age. Therefore, Chinese proponents of modernization have looked to western models. According to Thompson, the late Qing dynasty reformer, Kang Youwei, believed he had found a model for reform and "modernisation" in the Ancient Chinese Classics.

Philosopher Karl Popper said that progress was not fully adequate as a scientific explanation of social phenomena. More recently, Kirkpatrick Sale, a self-proclaimed neo-luddite author, wrote exclusively about progress as a myth, in an essay entitled "Five Facets of a Myth".

Iggers (1965) says that proponents of progress underestimated the extent of man's destructiveness and irrationality, while critics misunderstand the role of rationality and morality in human behavior.

In 1946, psychoanalyst Charles Baudouin claimed modernity has retained the "corollary" of the progress myth, the idea that the present is superior to the past, while at the same time insisting that it is free of the myth:

The last two centuries were familiar with the myth of progress. Our own century has adopted the myth of modernity. The one myth has replaced the other. ...

Men ceased to believe in progress; but only to pin their faith to more tangible realities, whose sole original significance had been that they were the instruments of progress. ..

This exaltation of the present ... is a corollary of that very faith in progress which people claim to have discarded. The present is superior to the past, by definition, only in a mythology of progress. Thus one retains the corollary while rejecting the principle. There is only one way of retaining a position of whose instability one is conscious. One must simply refrain from thinking.

A cyclical theory of history was adopted by Oswald Spengler (1880–1936), a German historian who wrote The Decline of the West in 1920. World War I, World War II, and the rise of totalitarianism demonstrated that progress was not automatic and that technological improvement did not necessarily guarantee democracy and moral advancement. British historian Arnold J. Toynbee (1889–1975) felt that Christianity would help modern civilization overcome its challenges.

The Jeffersonians said that history is not exhausted but that man may begin again in a new world. Besides rejecting the lessons of the past, they Americanized the idea of progress by democratizing and vulgarizing it to include the welfare of the common man as a form of republicanism. As Romantics deeply concerned with the past, collecting source materials and founding historical societies, the Founding Fathers were animated by clear principles. They saw man in control of his destiny, saw virtue as a distinguishing characteristic of a republic, and were concerned with happiness, progress, and prosperity. Thomas Paine, combining the spirit of rationalism and romanticism, pictured a time when America's innocence would sound like a romance, and concluded that the fall of America could mark the end of 'the noblest work of human wisdom.'

Historian J. B. Bury wrote in 1920:

To the minds of most people the desirable outcome of human development would be a condition of society in which all the inhabitants of the planet would enjoy a perfectly happy existence....It cannot be proved that the unknown destination towards which man is advancing is desirable. The movement may be Progress, or it may be in an undesirable direction and therefore not Progress..... The Progress of humanity belongs to the same order of ideas as Providence or personal immortality. It is true or it is false, and like them it cannot be proved either true or false. Belief in it is an act of faith.

In the postmodernist thought steadily gaining ground from the 1980s, the grandiose claims of the modernizers are steadily eroded, and the very concept of social progress is again questioned and scrutinized. In the new vision, radical modernizers like Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong appear as totalitarian despots, whose vision of social progress is held to be totally deformed. Postmodernists question the validity of 19th-century and 20th-century notions of progress—both on the capitalist and the Marxist side of the spectrum. They argue that both capitalism and Marxism over-emphasize technological achievements and material prosperity while ignoring the value of inner happiness and peace of mind. Postmodernism posits that both dystopia and utopia are one and the same, overarching grand narratives with impossible conclusions.

Some 20th-century authors refer to the "Myth of Progress" to refer to the idea that the human condition will inevitably improve. In 1932, English physician Montague David Eder wrote: "The myth of progress states that civilization has moved, is moving, and will move in a desirable direction. Progress is inevitable... Philosophers, men of science and politicians have accepted the idea of the inevitability of progress." Eder argues that the advancement of civilization is leading to greater unhappiness and loss of control in the environment. The strongest critics of the idea of progress complain that it remains a dominant idea in the 21st century, and shows no sign of diminished influence. As one fierce critic, British historian John Gray (b. 1948), concludes:

Faith in the liberating power of knowledge is encrypted into modern life. Drawing on some of Europe's most ancient traditions, and daily reinforced by the quickening advance of science, it cannot be given up by an act of will. The interaction of quickening scientific advance with unchanging human needs is a fate that we may perhaps temper, but cannot overcome... Those who hold to the possibility of progress need not fear. The illusion that through science humans can remake the world is an integral part of the modern condition. Renewing the eschatological hopes of the past, progress is an illusion with a future.

Recently the idea of progress has been generalized to psychology, being related with the concept of a goal, that is, progress is understood as "what counts as a means of advancing towards the end result of a given defined goal."

Antiquity

Historian J. B. Bury said that thought in ancient Greece was dominated by the theory of world-cycles or the doctrine of eternal return, and was steeped in a belief parallel to the Judaic "fall of man," but rather from a preceding "Golden Age" of innocence and simplicity. Time was generally regarded as the enemy of humanity which depreciates the value of the world. He credits the Epicureans with having had a potential for leading to the foundation of a theory of progress through their materialistic acceptance of the atomism of Democritus as the explanation for a world without an intervening deity.

For them, the earliest condition of men resembled that of the beasts, and from this primitive and miserable condition they laboriously reached the existing state of civilisation, not by external guidance or as a consequence of some initial design, but simply by the exercise of human intelligence throughout a long period.

Robert Nisbet and Gertrude Himmelfarb have attributed a notion of progress to other Greeks. Xenophanes said "The gods did not reveal to men all things in the beginning, but men through their own search find in the course of time that which is better."

Renaissance

During the Medieval period, science was to a large extent based on Scholastic (a method of thinking and learning from the Middle Ages) interpretations of Aristotle's work. The Renaissance of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries changed the mindset in Europe towards an empirical view, based on a pantheistic interpretation of Plato. This induced a revolution in curiosity about nature in general and scientific advance, which opened the gates for technical and economic advance. Furthermore, the individual potential was seen as a never-ending quest for being God-like, paving the way for a view of Man based on unlimited perfection and progress.

Age of Enlightenment (1650–1800)

In the Enlightenment, French historian and philosopher Voltaire (1694–1778) was a major proponent of progress. At first Voltaire's thought was informed by the idea of progress coupled with rationalism. His subsequent notion of the historical idea of progress saw science and reason as the driving forces behind societal advancement.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) argued that progress is neither automatic nor continuous and does not measure knowledge or wealth, but is a painful and largely inadvertent passage from barbarism through civilization toward enlightened culture and the abolition of war. Kant called for education, with the education of humankind seen as a slow process whereby world history propels mankind toward peace through war, international commerce, and enlightened self-interest.

Scottish theorist Adam Ferguson (1723–1816) defined human progress as the working out of a divine plan, though he rejected predestination. The difficulties and dangers of life provided the necessary stimuli for human development, while the uniquely human ability to evaluate led to ambition and the conscious striving for excellence. But he never adequately analyzed the competitive and aggressive consequences stemming from his emphasis on ambition even though he envisioned man's lot as a perpetual striving with no earthly culmination. Man found his happiness only in effort.

Some scholars consider the idea of progress that was affirmed with the Enlightenment, as a secularization of ideas from early Christianity, and a reworking of ideas from ancient Greece.

Romanticism and 19th century

In the 19th century, Romantic critics charged that progress did not automatically better the human condition, and in some ways could make it worse. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) reacted against the concept of progress as set forth by William Godwin and Condorcet because he believed that inequality of conditions is "the best (state) calculated to develop the energies and faculties of man". He said, "Had population and food increased in the same ratio, it is probable that man might never have emerged from the savage state". He argued that man's capacity for improvement has been demonstrated by the growth of his intellect, a form of progress which offsets the distresses engendered by the law of population.

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) criticized the idea of progress as the 'weakling's doctrines of optimism,' and advocated undermining concepts such as faith in progress, to allow the strong individual to stand above the plebeian masses. An important part of his thinking consists of the attempt to use the classical model of 'eternal recurrence of the same' to dislodge the idea of progress.

Iggers (1965) argues there was general agreement in the late 19th century that the steady accumulation of knowledge and the progressive replacement of conjectural, that is, theological or metaphysical, notions by scientific ones was what created progress. Most scholars concluded this growth of scientific knowledge and methods led to the growth of industry and the transformation of warlike societies into industrial and pacific ones. They agreed as well that there had been a systematic decline of coercion in government, and an increasing role of liberty and of rule by consent. There was more emphasis on impersonal social and historical forces; progress was increasingly seen as the result of an inner logic of society.

Marxist theory (late 19th century)

Marx developed a theory of historical materialism. He describes the mid-19th-century condition in The Communist Manifesto as follows:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty, and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all which is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.

Furthermore, Marx described the process of social progress, which in his opinion is based on the interaction between the productive forces and the relations of production:

No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.

Capitalism is thought by Marx as a process of continual change, in which the growth of markets dissolve all fixities in human life, and Marx argues that capitalism is progressive and non-reactionary. Marxism further states that capitalism, in its quest for higher profits and new markets, will inevitably sow the seeds of its own destruction. Marxists believe that, in the future, capitalism will be replaced by socialism and eventually communism.

Many advocates of capitalism such as Schumpeter agreed with Marx's analysis of capitalism as a process of continual change through creative destruction, but, unlike Marx, believed and hoped that capitalism could essentially go on forever.

Thus, by the beginning of the 20th century, two opposing schools of thought—Marxism and liberalism—believed in the possibility and the desirability of continual change and improvement. Marxists strongly opposed capitalism and the liberals strongly supported it, but the one concept they could both agree on was progress, which affirms the power of human beings to make, improve and reshape their society, with the aid of scientific knowledge, technology and practical experimentation. Modernity denotes cultures that embrace that concept of progress. (This is not the same as modernism, which was the artistic and philosophical response to modernity, some of which embraced technology while rejecting individualism, but more of which rejected modernity entirely.)