From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_English

| Old English | |

|---|---|

| Englisċ Ænglisċ | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈeŋɡliʃ] |

| Region | England (except Cornwall and the extreme north-west), southern and eastern Scotland, and some localities in the eastern fringes of modern Wales |

| Ethnicity | Anglo-Saxons |

| Era | Mostly developed into Middle English and Early Scots by the 13th century |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Runic, later Latin (Old English alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ang |

| ISO 639-3 | ang |

| ISO 639-6 | ango |

| Glottolog | olde1238 |

Old English (Englisċ, pronounced [ˈeŋɡliʃ]), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th century, and the first Old English literary works date from the mid-7th century. After the Norman conquest of 1066, English was replaced, for a time, by Anglo-Norman (a relative of French) as the language of the upper classes. This is regarded as marking the end of the Old English era, since during this period the English language was heavily influenced by Anglo-Norman, developing into a phase known now as Middle English in England and Early Scots in Scotland.

Old English developed from a set of Anglo-Frisian or Ingvaeonic dialects originally spoken by Germanic tribes traditionally known as the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. As the Germanic settlers became dominant in England, their language replaced the languages of Roman Britain: Common Brittonic, a Celtic language; and Latin, brought to Britain by the Roman invasion. Old English had four main dialects, associated with particular Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish and West Saxon. It was West Saxon that formed the basis for the literary standard of the later Old English period, although the dominant forms of Middle and Modern English would develop mainly from Mercian, and Scots from Northumbrian. The speech of eastern and northern parts of England was subject to strong Old Norse influence due to Scandinavian rule and settlement beginning in the 9th century.

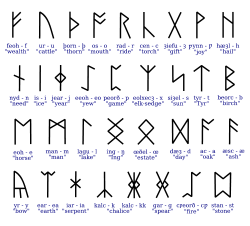

Old English is one of the West Germanic languages, and its closest relatives are Old Frisian and Old Saxon. Like other old Germanic languages, it is very different from Modern English and Modern Scots, and largely incomprehensible for Modern English or Modern Scots speakers without study. Within Old English grammar nouns, adjectives, pronouns and verbs have many inflectional endings and forms, and word order is much freer. The oldest Old English inscriptions were written using a runic system, but from about the 8th century this was replaced by a version of the Latin alphabet.

Etymology

Englisċ, from which the word English is derived, means 'pertaining to the Angles'. In Old English, this word was derived from Angles (one of the Germanic tribes who settled in parts of Great Britain in the 5th century). During the 9th century, all invading Germanic tribes were referred to as Englisċ. It has been hypothesised that the Angles acquired their name because their land on the coast of Jutland (now mainland Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein) resembled a fishhook. Proto-Germanic *anguz also had the meaning of 'narrow', referring to the shallow waters near the coast. That word ultimately goes back to Proto-Indo-European *h₂enǵʰ-, also meaning 'narrow'.

Another theory is that the derivation of 'narrow' is the more likely connection to angling (as in fishing), which itself stems from a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root meaning bend, angle. The semantic link is the fishing hook, which is curved or bent at an angle. In any case, the Angles may have been called such because they were a fishing people or were originally descended from such, and therefore England would mean 'land of the fishermen', and English would be 'the fishermen's language'.

History

Old English was not static, and its usage covered a period of 700 years, from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century to the late 11th century, some time after the Norman invasion. While indicating that the establishment of dates is an arbitrary process, Albert Baugh dates Old English from 450 to 1150, a period of full inflections, a synthetic language. Perhaps around 85% of Old English words are no longer in use, but those that survived are the basic elements of Modern English vocabulary.

Old English is a West Germanic language, and developed out of Ingvaeonic (also known as North Sea Germanic) dialects from the 5th century. It came to be spoken over most of the territory of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which became the Kingdom of England. This included most of present-day England, as well as part of what is now southeastern Scotland, which for several centuries belonged to the kingdom of Northumbria. Other parts of the island continued to use Celtic languages (Gaelic – and perhaps some Pictish – in most of Scotland, Medieval Cornish all over Cornwall and in adjacent parts of Devon, Cumbric perhaps to the 12th century in parts of Cumbria, and Welsh in Wales and possibly also on the English side of the Anglo-Welsh border); except in the areas of Scandinavian settlements, where Old Norse was spoken and Danish law applied.

Old English literacy developed after Christianisation in the late 7th century. The oldest surviving work of Old English literature is Cædmon's Hymn, which was composed between 658 and 680 but not written down until the early 8th century. There is a limited corpus of runic inscriptions from the 5th to 7th centuries, but the oldest coherent runic texts (notably the inscriptions on the Franks Casket) date to the early 8th century. The Old English Latin alphabet was introduced around the 8th century.

With the unification of several of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (outside the Danelaw) by Alfred the Great in the later 9th century, the language of government and literature became standardised around the West Saxon dialect (Early West Saxon). Alfred advocated education in English alongside Latin, and had many works translated into the English language; some of them, such as Pope Gregory I's treatise Pastoral Care, appear to have been translated by Alfred himself. In Old English, typical of the development of literature, poetry arose before prose, but Alfred chiefly inspired the growth of prose.

A later literary standard, dating from the late 10th century, arose under the influence of Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester, and was followed by such writers as the prolific Ælfric of Eynsham ("the Grammarian"). This form of the language is known as the "Winchester standard", or more commonly as Late West Saxon. It is considered to represent the "classical" form of Old English. It retained its position of prestige until the time of the Norman Conquest, after which English ceased for a time to be of importance as a literary language.

The history of Old English can be subdivided into:

- Prehistoric Old English (c. 450 to 650); for this period, Old English is mostly a reconstructed language as no literary witnesses survive (with the exception of limited epigraphic evidence). This language, or closely related group of dialects, spoken by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, and pre-dating documented Old English or Anglo-Saxon, has also been called Primitive Old English.

- Early Old English (c. 650 to 900), the period of the oldest manuscript traditions, with authors such as Cædmon, Bede, Cynewulf and Aldhelm.

- Late Old English (c. 900 to 1170), the final stage of the language leading up to the Norman conquest of England and the subsequent transition to Early Middle English.

The Old English period is followed by Middle English (12th to 15th century), Early Modern English (c. 1480 to 1650) and finally Modern English (after 1650), and in Scotland Early Scots (before 1450), Middle Scots (c. 1450 to 1700) and Modern Scots (after 1700).

Dialects

Just as Modern English is not monolithic, Old English varied according to place. Despite the diversity of language of the Germanic-speaking migrants who established Old English in England and southeastern Scotland, it is possible to reconstruct proto-Old English as a fairly unitary language. For the most part, the differences between the attested regional dialects of Old English developed within England and southeastern Scotland, rather than on the Mainland of Europe. Although from the tenth century Old English writing from all regions tended to conform to a written standard based on Late West Saxon, in speech Old English continued to exhibit much local and regional variation, which remained in Middle English and to some extent Modern English dialects.

The four main dialectal forms of Old English were Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish, and West Saxon. Mercian and Northumbrian are together referred to as Anglian. In terms of geography the Northumbrian region lay north of the Humber River; the Mercian lay north of the Thames and south of the Humber River; West Saxon lay south and southwest of the Thames; and the smallest, Kentish region lay southeast of the Thames, a small corner of England. The Kentish region, settled by the Jutes from Jutland, has the scantest literary remains. The term West Saxon actually is represented by two different dialects: Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon. Hogg has suggested that these two dialects would be more appropriately named Alfredian Saxon and Æthelwoldian Saxon, respectively, so that the naive reader would not assume that they are chronologically related.

Each of these four dialects was associated with an independent kingdom on the islands. Of these, Northumbria south of the Tyne, and most of Mercia, were overrun by the Vikings during the 9th century. The portion of Mercia that was successfully defended, and all of Kent, were then integrated into Wessex under Alfred the Great. From that time on, the West Saxon dialect (then in the form now known as Early West Saxon) became standardised as the language of government, and as the basis for the many works of literature and religious materials produced or translated from Latin in that period.

The later literary standard known as Late West Saxon (see History, above), although centred in the same region of the country, appears not to have been directly descended from Alfred's Early West Saxon. For example, the former diphthong /iy/ tended to become monophthongised to /i/ in EWS, but to /y/ in LWS.

Due to the centralisation of power and the destruction wrought by Viking invasions, there is relatively little written record of the non-West Saxon dialects after Alfred's unification. Some Mercian texts continued to be written, however, and the influence of Mercian is apparent in some of the translations produced under Alfred's programme, many of which were produced by Mercian scholars. Other dialects certainly continued to be spoken, as is evidenced by the continued variation between their successors in Middle and Modern English. In fact, what would become the standard forms of Middle English and of Modern English are descended from Mercian rather than West Saxon, while Scots developed from the Northumbrian dialect. It was once claimed that, owing to its position at the heart of the Kingdom of Wessex, the relics of Anglo-Saxon accent, idiom and vocabulary were best preserved in the dialect of Somerset.

For details of the sound differences between the dialects, see Phonological history of Old English § Dialects.

Influence of other languages

The language of the Anglo-Saxon settlers appears not to have been significantly affected by the native British Celtic languages which it largely displaced. The number of Celtic loanwords introduced into the language is very small, although dialect and toponymic terms are more often retained in western language contact zones (Cumbria, Devon, Welsh Marches and Borders and so on) than in the east. However, various suggestions have been made concerning possible influence that Celtic may have had on developments in English syntax in the post–Old English period, such as the regular progressive construction and analytic word order, as well as the eventual development of the periphrastic auxiliary verb do. These ideas have generally not received widespread support from linguists, particularly as many of the theorized Brittonicisms do not become widespread until the late Middle English and Early Modern English periods, in addition to the fact that similar forms exist in other modern Germanic languages.

Old English contained a certain number of loanwords from Latin, which was the scholarly and diplomatic lingua franca of Western Europe. It is sometimes possible to give approximate dates for the borrowing of individual Latin words based on which patterns of sound change they have undergone. Some Latin words had already been borrowed into the Germanic languages before the ancestral Angles and Saxons left continental Europe for Britain. More entered the language when the Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity and Latin-speaking priests became influential. It was also through Irish Christian missionaries that the Latin alphabet was introduced and adapted for the writing of Old English, replacing the earlier runic system. Nonetheless, the largest transfer of Latin-based (mainly Old French) words into English occurred after the Norman Conquest of 1066, and thus in the Middle English rather than the Old English period.

Another source of loanwords was Old Norse, which came into contact with Old English via the Scandinavian rulers and settlers in the Danelaw from the late 9th century, and during the rule of Cnut and other Danish kings in the early 11th century. Many place names in eastern and northern England are of Scandinavian origin. Norse borrowings are relatively rare in Old English literature, being mostly terms relating to government and administration. The literary standard, however, was based on the West Saxon dialect, away from the main area of Scandinavian influence; the impact of Norse may have been greater in the eastern and northern dialects. Certainly in Middle English texts, which are more often based on eastern dialects, a strong Norse influence becomes apparent. Modern English contains many, often everyday, words that were borrowed from Old Norse, and the grammatical simplification that occurred after the Old English period is also often attributed to Norse influence.

The influence of Old Norse certainly helped move English from a synthetic language along the continuum to a more analytic word order, and Old Norse most likely made a greater impact on the English language than any other language. The eagerness of Vikings in the Danelaw to communicate with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours produced a friction that led to the erosion of the complicated inflectional word endings. Simeon Potter notes:

No less far-reaching was the influence of Scandinavian upon the inflexional endings of English in hastening that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms which gradually spread from north to south. It was, after all, a salutary influence. The gain was greater than the loss. There was a gain in directness, in clarity, and in strength.

The strength of the Viking influence on Old English appears from the fact that the indispensable elements of the language – pronouns, modals, comparatives, pronominal adverbs (like hence and together), conjunctions and prepositions – show the most marked Danish influence; the best evidence of Scandinavian influence appears in the extensive word borrowings because, as Jespersen indicates, no texts exist in either Scandinavia or Northern England from this time to give certain evidence of an influence on syntax. The effect of Old Norse on Old English was substantive, pervasive, and of a democratic character. Old Norse and Old English resembled each other closely like cousins, and with some words in common, speakers roughly understood each other; in time the inflections melted away and the analytic pattern emerged. It is most important to recognize that in many words the English and Scandinavian language differed chiefly in their inflectional elements. The body of the word was so nearly the same in the two languages that only the endings would put obstacles in the way of mutual understanding. In the mixed population which existed in the Danelaw, these endings must have led to much confusion, tending gradually to become obscured and finally lost. This blending of peoples and languages resulted in "simplifying English grammar".

Phonology

The inventory of Early West Saxon surface phones is as follows.

|

|

Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m |

|

(n̥) n |

|

|

(ŋ) |

|

| Stop | p b |

|

t d |

|

|

k (ɡ) |

|

| Affricate |

|

|

|

tʃ (dʒ) |

|

|

|

| Fricative | f (v) | θ (ð) | s (z) | ʃ | (ç) | x ɣ | (h) |

| Approximant |

|

|

(l̥) l |

|

j | (ʍ) w |

|

| Trill |

|

|

(r̥) r |

|

|

|

|

The sounds enclosed in parentheses in the chart above are not considered to be phonemes:

- [dʒ] is an allophone of /j/ occurring after /n/ and when geminated (doubled).

- [ŋ] is an allophone of /n/ occurring before [k] and [ɡ].

- [v, ð, z] are voiced allophones of /f, θ, s/ respectively, occurring between vowels or voiced consonants when the preceding sound was stressed.

- [h, ç] are allophones of /x/ occurring at the beginning of a word or after a front vowel, respectively.

- [ɡ] is an allophone of /ɣ/ occurring after /n/ or when doubled. At some point before the Middle English period, [ɡ] also became the pronunciation word-initially.

- the voiceless sonorants [w̥, l̥, n̥, r̥] occur after [h] in the sequences /xw, xl, xn, xr/.

The above system is largely similar to that of Modern English, except that [ç, x, ɣ, l̥, n̥, r̥] (and [w̥] for most speakers) have generally been lost, while the voiced affricate and fricatives (now also including /ʒ/) have become independent phonemes, as has /ŋ/.

|

|

Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i iː | y yː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | ||

| Open | æ æː | ɑ ɑː | (ɒ) | |

The open back rounded vowel [ɒ] was an allophone of short /ɑ/ which occurred in stressed syllables before nasal consonants (/m/ and /n/). It was variously spelled either ⟨a⟩ or ⟨o⟩.

The Anglian dialects also had the mid front rounded vowel /ø(ː)/, spelled ⟨œ⟩, which had emerged from i-umlaut of /o(ː)/. In West Saxon and Kentish, it had already merged with /e(ː)/ before the first written prose.

| First element |

Short (monomoraic) |

Long (bimoraic) |

|---|---|---|

| Close | iy̯ | iːy̯ |

| Mid | eo̯ | eːo̯ |

| Open | æɑ̯ | æːɑ̯ |

Other dialects had different systems of diphthongs. For example, the Northumbrian dialect retained /i(ː)o̯/, which had merged with /e(ː)o̯/ in West Saxon.

For more on dialectal differences, see Phonological history of Old English (dialects).

Sound changes

Some of the principal sound changes occurring in the pre-history and history of Old English were the following:

- Fronting of [ɑ(ː)] to [æ(ː)] except when nasalised or followed by a nasal consonant ("Anglo-Frisian brightening"), partly reversed in certain positions by later "a-restoration" or retraction.

- Monophthongisation of the diphthong [ai], and modification of remaining diphthongs to the height-harmonic type.

- Diphthongisation of long and short front vowels in certain positions ("breaking").

- Palatalisation of velars [k], [ɡ], [ɣ], [sk] to [tʃ], [dʒ], [j], [ʃ] in certain front-vowel environments.

- The process known as i-mutation (which for example led to modern mice as the plural of mouse).

- Loss of certain weak vowels in word-final and medial positions; reduction of remaining unstressed vowels.

- Diphthongisation of certain vowels before certain consonants when preceding a back vowel ("back mutation").

- Loss of /x/ between vowels or between a voiced consonant and a vowel, with lengthening of the preceding vowel.

- Collapse of two consecutive vowels into a single vowel.

- "Palatal umlaut", which has given forms such as six (compare German sechs).

For more details of these processes, see the main article, linked above. For sound changes before and after the Old English period, see Phonological history of English.

Grammar

Morphology

Nouns decline for five cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental; three genders: masculine, feminine, neuter; and two numbers: singular, and plural; and are strong or weak. The instrumental is vestigial and only used with the masculine and neuter singular and often replaced by the dative. Only pronouns and strong adjectives retain separate instrumental forms. There is also sparse early Northumbrian evidence of a sixth case: the locative. The evidence comes from Northumbrian Runic texts (e.g., ᚩᚾ ᚱᚩᛞᛁ on rodi "on the Cross").

Adjectives agree with nouns in case, gender, and number, and can be either strong or weak. Pronouns and sometimes participles agree in case, gender, and number. First-person and second-person personal pronouns occasionally distinguish dual-number forms. The definite article sē and its inflections serve as a definite article ("the"), a demonstrative adjective ("that"), and demonstrative pronoun. Other demonstratives are þēs ("this"), and ġeon ("that over there"). These words inflect for case, gender, and number. Adjectives have both strong and weak sets of endings, weak ones being used when a definite or possessive determiner is also present.

Verbs conjugate for three persons: first, second, and third; two numbers: singular, plural; two tenses: present, and past; three moods: indicative, subjunctive, and imperative; and are strong (exhibiting ablaut) or weak (exhibiting a dental suffix). Verbs have two infinitive forms: bare and bound; and two participles: present and past. The subjunctive has past and present forms. Finite verbs agree with subjects in person and number. The future tense, passive voice, and other aspects are formed with compounds. Adpositions are mostly before but are often after their object. If the object of an adposition is marked in the dative case, an adposition may conceivably be located anywhere in the sentence.

Remnants of the Old English case system in Modern English are in the forms of a few pronouns (such as I/me/mine, she/her, who/whom/whose) and in the possessive ending -'s, which derives from the masculine and neuter genitive ending -es. The modern English plural ending -(e)s derives from the Old English -as, but the latter applied only to "strong" masculine nouns in the nominative and accusative cases; different plural endings were used in other instances. Old English nouns had grammatical gender, while modern English has only natural gender. Pronoun usage could reflect either natural or grammatical gender when those conflicted, as in the case of ƿīf, a neuter noun referring to a female person.

In Old English's verbal compound constructions are the beginnings of the compound tenses of Modern English. Old English verbs include strong verbs, which form the past tense by altering the root vowel, and weak verbs, which use a suffix such as -de. As in Modern English, and peculiar to the Germanic languages, the verbs formed two great classes: weak (regular), and strong (irregular). Like today, Old English had fewer strong verbs, and many of these have over time decayed into weak forms. Then, as now, dental suffixes indicated the past tense of the weak verbs, as in work and worked.

Syntax

Old English syntax is similar to that of modern English. Some differences are consequences of the greater level of nominal and verbal inflection, allowing freer word order.

- Default word order is verb-second in main clauses, and verb-final in subordinate clauses

- No do-support in questions and negatives. Questions were usually formed by inverting subject and finite verb, and negatives by placing ne before the finite verb, regardless of which verb.

- Multiple negatives can stack up in a sentence intensifying each other (negative concord).

- Sentences with subordinate clauses of the type "when X, Y" (e.g. "When I got home, I ate dinner") don't use a wh-type conjunction, but rather a th-type correlative conjunction such as þā, otherwise meaning "then" (e.g. þā X, þā Y in place of "when X, Y"). The wh-words are used only as interrogatives and as indefinite pronouns.

- Similarly, wh- forms were not used as relative pronouns. Instead, the indeclinable word þe is used, often preceded by (or replaced by) the appropriate form of the article/demonstrative se.

Orthography

Old English was first written in runes, using the futhorc—a rune set derived from the Germanic 24-character elder futhark, extended by five more runes used to represent Anglo-Saxon vowel sounds and sometimes by several more additional characters. From around the 8th century, the runic system came to be supplanted by a (minuscule) half-uncial script of the Latin alphabet introduced by Irish Christian missionaries. This was replaced by Insular script, a cursive and pointed version of the half-uncial script. This was used until the end of the 12th century when continental Carolingian minuscule (also known as Caroline) replaced the insular.

The Latin alphabet of the time still lacked the letters ⟨j⟩ and ⟨w⟩, and there was no ⟨v⟩ as distinct from ⟨u⟩; moreover native Old English spellings did not use ⟨k⟩, ⟨q⟩ or ⟨z⟩. The remaining 20 Latin letters were supplemented by four more: ⟨æ⟩ (æsc, modern ash) and ⟨ð⟩ (ðæt, now called eth or edh), which were modified Latin letters, and thorn ⟨þ⟩ and wynn ⟨ƿ⟩, which are borrowings from the futhorc. A few letter pairs were used as digraphs, representing a single sound. Also used was the Tironian note ⟨⁊⟩ (a character similar to the digit 7) for the conjunction and. A common scribal abbreviation was a thorn with a stroke ⟨ꝥ⟩, which was used for the pronoun þæt. Macrons over vowels were originally used not to mark long vowels (as in modern editions), but to indicate stress, or as abbreviations for a following m or n.

Modern editions of Old English manuscripts generally introduce some additional conventions. The modern forms of Latin letters are used, including ⟨g⟩ in place of the insular G, ⟨s⟩ for long S, and others which may differ considerably from the insular script, notably ⟨e⟩, ⟨f⟩ and ⟨r⟩. Macrons are used to indicate long vowels, where usually no distinction was made between long and short vowels in the originals. (In some older editions an acute accent mark was used for consistency with Old Norse conventions.) Additionally, modern editions often distinguish between velar and palatal ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ by placing dots above the palatals: ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩. The letter wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ is usually replaced with ⟨w⟩, but æsc, eth and thorn are normally retained (except when eth is replaced by thorn).

In contrast with Modern English orthography, that of Old English was reasonably regular, with a mostly predictable correspondence between letters and phonemes. There were not usually any silent letters—in the word cniht, for example, both the ⟨c⟩ and ⟨h⟩ were pronounced (/knixt ~ kniçt/) unlike the ⟨k⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ in the modern knight (/naɪt/). The following table lists the Old English letters and digraphs together with the phonemes they represent, using the same notation as in the Phonology section above.

| Character | IPA transcription | Description and notes |

|---|---|---|

| a | /ɑ/, /ɑː/ | Spelling variations like ⟨land⟩ ~ ⟨lond⟩ ("land") suggest the short vowel had a rounded allophone [ɒ] before /m/ and /n/ when it occurred in stressed syllables. |

| ā | /ɑː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /ɑ/. |

| æ | /æ/, /æː/ | Formerly the digraph ⟨ae⟩ was used; ⟨æ⟩ became more common during the 8th century, and was standard after 800. In 9th-century Kentish manuscripts, a form of ⟨æ⟩ that was missing the upper hook of the ⟨a⟩ part was used; it is not clear whether this represented /æ/ or /e/. See also ę. |

| ǣ | /æː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /æ/. |

| b | /b/ |

|

| [v] (an allophone of /f/) | Used in this way in early texts (before 800). For example, the word "sheaves" is spelled scēabas in an early text, but later (and more commonly) as scēafas. | |

| c | /k/ |

|

| /tʃ/ | The /tʃ/ pronunciation is sometimes written with a diacritic by modern editors: most commonly ⟨ċ⟩, sometimes ⟨č⟩ or ⟨ç⟩. Before a consonant letter the pronunciation is always /k/; word-finally after ⟨i⟩ it is always /tʃ/. Otherwise, a knowledge of the history of the word is needed to predict the pronunciation with certainty, although it is most commonly /tʃ/ before front vowels (other than [y]) and /k/ elsewhere. (For details, see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization.) See also the digraphs cg, sc. | |

| cg | (between vowels) [ddʒ], rarely [ɡɡ] | Proto-Germanic *g was palatalized when it underwent West Germanic gemination, resulting in the voiced palatal geminate [ddʒ] (which can be phonemically analyzed as /jj/). Consequently, the voiced velar geminate [ɡɡ] (which can be phonemically analyzed as /ɣɣ/) was rare in Old English, and its etymological origin in the words in which it occurs (such as frocga 'frog') is unclear. Alternative spellings of either geminate included ⟨gg⟩, ⟨gc⟩, ⟨cgg⟩, ⟨ccg⟩ and ⟨gcg⟩.[44][45] The two geminates were not distinguished in Old English orthography; in modern editions, the palatal geminate is sometimes written ⟨ċġ⟩ to distinguish it from velar ⟨cg⟩. |

| (after /n/) [dʒ] or [g] | After /n/, /j/ was realized as [dʒ] and /ɣ/ was realized as [ɡ]. The spellings ⟨ncg⟩, ⟨ngc⟩ and even ⟨ncgg⟩ were occasionally used instead of the usual ⟨ng⟩. The addition of ⟨c⟩ to ⟨g⟩ in spellings such as ⟨cynincg⟩ and ⟨cyningc⟩ for ⟨cyning⟩ may have been a means of showing that the word was pronounced with a stop rather than a fricative; spellings with just ⟨nc⟩ such as ⟨cyninc⟩ are also found. To disambiguate, the cluster ending in the palatal affricate is sometimes written ⟨nċġ⟩ (or ⟨nġċ⟩) by modern editors. | |

| d | /d/ | In the earliest texts it also represented /θ/ (see þ). |

| ð | /θ/, including its allophone [ð] | Called ðæt in Old English; now called eth or edh. Derived from the insular form of ⟨d⟩ with the addition of a cross-bar. Both ⟨þ⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ could represent either allophone of /θ/, voiceless [θ] or voiced [ð], but some texts show a tendency to use ⟨þ⟩ at the start of words and ⟨ð⟩ in the middle or at the end of a word. Also see þ. |

| e | /e/, /eː/ |

|

| ę | /æ/, /æː/ | A modern editorial substitution for the modified Kentish form of ⟨æ⟩ (see æ). Compare e caudata, ę. |

| ē | /eː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /e/. |

| ea | /æɑ̯/, /æːɑ̯/ | Sometimes stands for /ɑ/ after ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩ (see palatal diphthongization). |

| ēa | /æːɑ̯/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /æɑ̯/. Sometimes stands for /ɑː/ after ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩. |

| eo | /eo̯/, /eːo̯/ | Sometimes stands for /o/ after ⟨ċ⟩ or ⟨ġ⟩ (see palatal diphthongization). |

| ēo | /eːo̯/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /eo̯/. |

| f | /f/, including its allophone [v] (but see b) |

|

| g | /ɣ/, including its allophone [ɡ]; or /j/, including its allophone [dʒ], which occurs after ⟨n⟩ | In Old English manuscripts, this letter usually took its insular form ⟨ᵹ⟩ (see also: yogh). The [j] and [dʒ] pronunciations are sometimes written ⟨ġ⟩ in modern editions. Word-initially before another consonant letter, the pronunciation is always the velar fricative [ɣ]. Word-finally after ⟨i⟩, it is always palatal [j]. Otherwise, a knowledge of the history of the word in question is needed to predict the pronunciation with certainty, although it is most commonly /j/ before and after front vowels (other than [y]) and /ɣ/ elsewhere. (For details, see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization.) |

| h | /x/, including its allophones [h, ç] | The combinations ⟨hl⟩, ⟨hr⟩, ⟨hn⟩, ⟨hw⟩ may have been realized as devoiced versions of the second consonants instead of as sequences starting with [h]. |

| i | /i/, /iː/, rarely [j] | Although the spelling ⟨g⟩ is used for the palatal consonant /j/ from the earliest Old English texts, the letter ⟨i⟩ is also found as a minority spelling of /j/. West Saxon scribes came to prefer to use ⟨ri⟩ rather than ⟨rg⟩ to spell the /rj/ sequence found in verbs like herian and swerian, whereas Mercian and Northumbrian texts generally used ⟨rg⟩ in the spelling of these words. |

| ī | /iː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /i/. |

| ie | /iy̯/, /iːy̯/ |

|

| īe | /iːy̯/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /iy̯/. |

| io | /io̯/, /iːo̯/ | By the time of the first written prose, /i(ː)o̯/ had merged with /e(ː)o̯/ in every dialect but Northumbrian, where it was preserved until Middle English. In Early West Saxon /e(ː)o̯/ was often written ⟨io⟩ instead of ⟨eo⟩, but by Late West Saxon only the ⟨eo⟩ spelling remained common. |

| īo | /iːo̯/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /io̯/. |

| k | /k/ | Rarely used; this sound is normally represented by ⟨c⟩. |

| l | /l/ | Probably velarised [ɫ] (as in Modern English) when in coda position. |

| m | /m/ |

|

| n | /n/, including its allophone [ŋ] |

|

| o | /o/, /oː/ | See also a. |

| ō | /oː/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /o/. |

| oe | /ø/, /øː/ (in dialects having that sound) |

|

| ōe | /øː/ | Used in modern editions, to distinguish from short /ø/. |

| p | /p/ |

|

| qu | /kw/ | A rare spelling of /kw/, which was usually written as ⟨cƿ⟩ (⟨cw⟩ in modern editions). |

| r | /r/ | The exact nature of Old English /r/ is not known; it may have been an alveolar approximant [ɹ] as in most modern English, an alveolar flap [ɾ], or an alveolar trill [r]. |

| s | /s/, including its allophone [z] |

|

| sc | /ʃ/ or occasionally /sk/ | /ʃ/ is always geminate /ʃ:/ between vowels: thus fisċere ("fisherman") was pronounced /ˈfiʃ.ʃe.re/. When non-initial, ⟨sc⟩ is pronounced /sk/ if the next sound had been a back vowel (/ɑ/, /o/, /u/) at the time of palatalization, giving rise to contrasts such as fisċ /fiʃ/ ("fish") next to its plural fiscas /ˈfis.kɑs/. See palatalization. |

| t | /t/ |

|

| th | Represented /θ/ in the earliest texts (see þ) |

|

| þ | /θ/, including its allophone [ð] | Called thorn and derived from the rune of the same name. In the earliest texts ⟨d⟩ or ⟨th⟩ was used for this phoneme, but these were later replaced in this function by eth ⟨ð⟩ and thorn ⟨þ⟩. Eth was first attested (in definitely dated materials) in the 7th century, and thorn in the 8th. Eth was more common than thorn before Alfred's time. From then onward, thorn was used increasingly often at the start of words, while eth was normal in the middle and at the end of words, although usage varied in both cases. Some modern editions use only thorn. See also Pronunciation of English ⟨th⟩. |

| u | /u/, /uː/; also sometimes /w/ (see ƿ) |

|

| uu | Sometimes used for /w/ (see ƿ) |

|

| ū | /uː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /u/. |

| w | /w/ | Used in modern editions as a substitute for the character ⟨ƿ⟩. |

| ƿ | /w/ | Called wynn and derived from the rune of the same name. In earlier texts by continental scribes, and also later in the north, /w/ was represented by ⟨u⟩ or ⟨uu⟩. In modern editions, wynn is replaced by ⟨w⟩, to prevent confusion with ⟨p⟩. |

| x | /ks/ |

|

| y | /y/, /yː/ |

|

| ȳ | /yː/ | Used in modern editions to distinguish from short /y/. |

| z | /ts/ | A rare spelling for /ts/; e.g. betst ("best") is occasionally spelt bezt. |

Doubled consonants are geminated; the geminate fricatives ⟨ff⟩, ⟨ss⟩ and ⟨ðð⟩/⟨þþ⟩/⟨ðþ⟩/⟨þð⟩ are always voiceless [ff], [ss], [θθ].

Literature

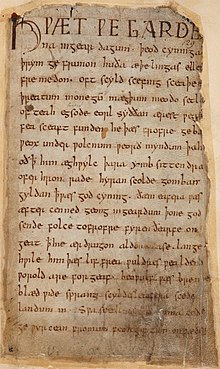

Hƿæt ƿē Gārde/na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...

"Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the folk-kings..."

The corpus of Old English literature is small but still significant, with some 400 surviving manuscripts. The pagan and Christian streams mingle in Old English, one of the richest and most significant bodies of literature preserved among the early Germanic peoples. In his supplementary article to the 1935 posthumous edition of Bright's Anglo-Saxon Reader, Dr. James Hulbert writes:

In such historical conditions, an incalculable amount of the writings of the Anglo-Saxon period perished. What they contained, how important they were for an understanding of literature before the Conquest, we have no means of knowing: the scant catalogues of monastic libraries do not help us, and there are no references in extant works to other compositions....How incomplete our materials are can be illustrated by the well-known fact that, with few and relatively unimportant exceptions, all extant Anglo-Saxon poetry is preserved in four manuscripts.

Some of the most important surviving works of Old English literature are Beowulf, an epic poem; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a record of early English history; the Franks Casket, an inscribed early whalebone artefact; and Cædmon's Hymn, a Christian religious poem. There are also a number of extant prose works, such as sermons and saints' lives, biblical translations, and translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers, legal documents, such as laws and wills, and practical works on grammar, medicine, and geography. Still, poetry is considered the heart of Old English literature. Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous, with a few exceptions, such as Bede and Cædmon. Cædmon, the earliest English poet known by name, served as a lay brother in the monastery at Whitby.

Beowulf

The first example is taken from the opening lines of the folk-epic Beowulf, a poem of some 3,000 lines. This passage describes how Hrothgar's legendary ancestor Scyld was found as a baby, washed ashore, and adopted by a noble family. The translation is literal and represents the original poetic word order. As such, it is not typical of Old English prose. The modern cognates of original words have been used whenever practical to give a close approximation of the feel of the original poem.

The words in brackets are implied in the Old English by noun case and the bold words in brackets are explanations of words that have slightly different meanings in a modern context. Notice how what is used by the poet where a word like lo or behold would be expected. This usage is similar to what-ho!, both an expression of surprise and a call to attention.

English poetry is based on stress and alliteration. In alliteration, the first consonant in a word alliterates with the same consonant at the beginning of another word, as with Gār-Dena and ġeār-dagum. Vowels alliterate with any other vowel, as with æþelingas and ellen. In the text below, the letters that alliterate are bolded.

|

|

Original | Representation with constructed cognates |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hƿæt! ƿē Gār-Dena in ġeār-dagum, | What! We of Gare-Danes (lit. Spear-Danes) in yore-days, |

| þēod-cyninga, þrym ġefrūnon, | of thede (nation/people)-kings, did thrum (glory) frain (learn about by asking), | |

| hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon. | how those athelings (noblemen) did ellen (fortitude/courage/zeal) freme (promote). | |

| Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum, | Oft did Scyld Scefing of scather threats (troops), | |

| 5 | monegum mǣġþum, meodosetla oftēah, | of many maegths (clans; cf. Irish cognate Mac-), of mead-settees atee (deprive), |

| egsode eorlas. Syððan ǣrest ƿearð | [and] ugg (induce loathing in, terrify; related to "ugly") earls. Sith (since, as of when) erst (first) [he] worthed (became) | |

| fēasceaft funden, hē þæs frōfre ġebād, | [in] fewship (destitute) found, he of this frover (comfort) abode, | |

| ƿēox under ƿolcnum, ƿeorðmyndum þāh, | [and] waxed under welkin (firmament/clouds), [and amid] worthmint (honour/worship) theed (throve/prospered) | |

| oðþæt him ǣġhƿylc þāra ymbsittendra | oth that (until that) him each of those umsitters (those "sitting" or dwelling roundabout) | |

| 10 | ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde, | over whale-road (kenning for "sea") hear should, |

| gomban gyldan. Þæt ƿæs gōd cyning! | [and] yeme (heed/obedience; related to "gormless") yield. That was [a] good king! |

Here is a natural enough Modern English translation, although the phrasing of the Old English passage has often been stylistically preserved, even though it is not usual in Modern English:

What! We spear-Danes in ancient days inquired about the glory of the nation-kings, how the princes performed bravery.

Often Shield the son/descendant of Sheaf ripped away the mead-benches from many tribes' enemy bands – he terrified men!

After destitution was first experienced (by him), he met with consolation for that; he grew under the clouds of the sky and flourished in adulation, until all of the neighbouring people had to obey him over the whale-road (i.e. the sea), and pay tribute to the man. That was a good king!

The Lord's Prayer

This text of the Lord's Prayer is presented in the standardised Early West Saxon dialect.

| Line | Original | IPA | Word-for-word translation into Modern English | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Fæder ūre þū þe eart on heofonum, | [ˈfæ.der ˈuː.re θuː θe æɑ̯rt on ˈheo̯.vo.num] | Father Ours, thou which art in heavens, | Our Father, who art in heaven, |

| [2] | Sīe þīn nama ġehālgod. | [siːy̯ θiːn ˈnɒ.mɑ jeˈhɑːɫ.ɣod] | Be thine name hallowed. | Hallowed be thy name. |

| [3] | Tōbecume þīn rīċe, | [ˌtoː.beˈku.me θiːn ˈriː.t͡ʃe] | To be come [is] thine kingdom, | Thy kingdom come, |

| [4] | Ġeweorðe þīn willa, on eorðan swā swā on heofonum. | [jeˈweo̯rˠ.ðe θiːn ˈwil.lɑ on ˈeo̯rˠ.ðan swɑː swɑː on ˈheo̯.vo.num] | Let there be thine will, on earth as in heavens. | Thy will be done on earth as in heaven. |

| [5] | Ūrne dæġhwamlīcan hlāf sele ūs tōdæġ, | [ˈuːrˠ.ne ˈdæj.ʍɑmˌliː.kɑn hl̥ɑːf ˈse.le uːs toːˈdæj] | Our daily loaf sell us today, | Give us this day our daily bread, |

| [6] | And forġief ūs ūre gyltas, swā swā wē forġiefaþ ūrum gyltendum. | [ɒnd forˠˈjiy̯f uːs ˈuː.re ˈɣyl.tɑs swɑː swɑː weː forˠˈjiy̯.vɑθ uː.rum ˈɣyl.ten.dum] | And forgive us our guilts, as we forgiveth our guilters. | And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors. |

| [7] | And ne ġelǣd þū ūs on costnunge, ac ālīes ūs of yfele. | [ɒnd ne jeˈlæːd θuː uːs on ˈkost.nuŋ.ɡe ɑk ɑːˈliːy̯s uːs of ˈy.ve.le] | And not lead thou us in temptations, but allay us of evil. | And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. |

| [8] | Sōðlīċe. | [ˈsoːðˌliː.t͡ʃe] | Amen. | Amen. |

Charter of Cnut

This is a proclamation from King Cnut the Great to his earl Thorkell the Tall and the English people written in AD 1020. Unlike the previous two examples, this text is prose rather than poetry. For ease of reading, the passage has been divided into sentences while the pilcrows represent the original division.

| Original | Representation with constructed cognates |

|---|---|

| ¶ Cnut cyning gret his arcebiscopas and his leod-biscopas and Þurcyl eorl and ealle his eorlas and ealne his þeodscype, tƿelfhynde and tƿyhynde, gehadode and læƿede, on Englalande freondlice. | ¶ Cnut, king, greets his archbishops and his lede'(people's)'-bishops and Thorkell, earl, and all his earls and all his peopleship, greater (having a 1200 shilling weregild) and lesser (200 shilling weregild), hooded(ordained to priesthood) and lewd(lay), in England friendly. |

| And ic cyðe eoƿ, þæt ic ƿylle beon hold hlaford and unsƿicende to godes gerihtum and to rihtre ƿoroldlage. | And I kithe(make known/couth to) you, that I will be [a] hold(civilised) lord and unswiking(uncheating) to God's rights(laws) and to [the] rights(laws) worldly. |

| ¶ Ic nam me to gemynde þa geƿritu and þa ƿord, þe se arcebiscop Lyfing me fram þam papan brohte of Rome, þæt ic scolde æghƿær godes lof upp aræran and unriht alecgan and full frið ƿyrcean be ðære mihte, þe me god syllan ƿolde. | ¶ I nam(took) me to mind the writs and the word that the Archbishop Lyfing me from the Pope brought of Rome, that I should ayewhere(everywhere) God's love(praise) uprear(promote), and unright(outlaw) lies, and full frith(peace) work(bring about) by the might that me God would(wished) [to] sell'(give). |

| ¶ Nu ne ƿandode ic na minum sceattum, þa hƿile þe eoƿ unfrið on handa stod: nu ic mid-godes fultume þæt totƿæmde mid-minum scattum. | ¶ Now, ne went(withdrew/changed) I not my shot(financial contribution, cf. Norse cognate in scot-free) the while that you stood(endured) unfrith(turmoil) on-hand: now I, mid(with) God's support, that [unfrith] totwemed(separated/dispelled) mid(with) my shot(financial contribution). |

| Þa cydde man me, þæt us mara hearm to fundode, þonne us ƿel licode: and þa for ic me sylf mid-þam mannum þe me mid-foron into Denmearcon, þe eoƿ mæst hearm of com: and þæt hæbbe mid-godes fultume forene forfangen, þæt eoƿ næfre heonon forð þanon nan unfrið to ne cymð, þa hƿile þe ge me rihtlice healdað and min lif byð. | Tho(then) [a] man kithed(made known/couth to) me that us more harm had found(come upon) than us well liked(equalled): and tho(then) fore(travelled) I, meself, mid(with) those men that mid(with) me fore(travelled), into Denmark that [to] you most harm came of(from): and that[harm] have [I], mid(with) God's support, afore(previously) forefangen(forestalled) that to you never henceforth thence none unfrith(breach of peace) ne come the while that ye me rightly hold(behold as king) and my life beeth. |

The following is a natural Modern English translation, with the overall structure of the Old English passage preserved. Even though "earl" is used to translate its Old English cognate "eorl", "eorl" in Old English does not correspond exactly to "earl" of the later medieval period:

King Cnut kindly greets his archbishops and his provincial bishops and Earl Thorkell, and all his earls, and all his people, both those with a weregild of 1,200 shillings and those with a weregild of 200 shillings, both ordained and layman, in England.

And I declare to you, that I will be a kind lord, and faithful to God's laws and to proper secular law.

I recalled the writings and words which the archbishop Lyfing brought to me from the Pope of Rome, that I must promote the worship of God everywhere, and suppress unrighteousness, and promote perfect peace with the power which God would give me.

I never hesitated from my peace payments (e.g. to the Vikings) while you had strife at hand. But with God's help and my payments, that went away.

At that time, I was told that we had been harmed more than we liked; and I departed with the men who accompanied me into Denmark, from where the most harm has come to you; and I have already prevented it with God's help, so that from now on, strife will never come to you from there, while you regard me rightly and my life persists.

Dictionaries

Early history

The earliest history of Old English lexicography lies in the Anglo-Saxon period itself, when English-speaking scholars created English glosses on Latin texts. At first these were often marginal or interlinear glosses, but soon came to be gathered into word-lists such as the Épinal-Erfurt, Leiden and Corpus Glossaries. Over time, these word-lists were consolidated and alphabeticised to create extensive Latin-Old English glossaries with some of the character of dictionaries, such as the Cleopatra Glossaries, the Harley Glossary and the Brussels Glossary. In some cases, the material in these glossaries continued to be circulated and updated in Middle English glossaries, such as the Durham Plant-Name Glossary and the Laud Herbal Glossary.

Old English lexicography was revived in the early modern period, drawing heavily on Anglo-Saxons' own glossaries. The major publication at this time was William Somner's Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum. The next substantial Old English dictionary was Joseph Bosworth's Anglo-Saxon Dictionary of 1838.

Modern

In modern scholarship, the following dictionaries remain current:

- Cameron, Angus, et al. (ed.) (1983–). Dictionary of Old English. Toronto: Published for the Dictionary of Old English Project, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto by the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies. Initially issued on microfiche and subsequently as a CD-ROM, the dictionary is now primarily published online at https://www.doe.utoronto.ca. This generally supersedes previous dictionaries where available. As of September 2018, the dictionary covered A-I.

- Bosworth, Joseph and T. Northcote Toller. (1898). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. The main research dictionary for Old English, unless superseded by the Dictionary of Old English. Various digitisations are available open-access, including at http://bosworth.ff.cuni.cz/. Due to errors and omissions in the 1898 publication, this needs to be read in conjunction with:

- T. Northcote Toller. (1921). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Alistair Campbell (1972). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Enlarged addenda and corrigenda. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Clark Hall, J. R. (1969). A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. 4th rev. edn by Herbet D. Meritt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Occasionally more accurate than Bosworth-Toller, and widely used as a reading dictionary. Various digitisations are available, including here.

- Roberts, Jane and Christian Kay, with Lynne Grundy, A Thesaurus of Old English in Two Volumes, Costerus New Series, 131–32, 2nd rev. impression, 2 vols (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2000), also available online. A thesaurus based on the definitions in Bosworth-Toller and the structure of Roget's Thesaurus.

Though focused on later periods, the Oxford English Dictionary, Middle English Dictionary, Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue, and Historical Thesaurus of English all also include material relevant to Old English.

Modern legacy

Like other historical languages, Old English has been used by scholars and enthusiasts of later periods to create texts either imitating Old English literature or deliberately transferring it to a different cultural context. Examples include Alistair Campbell and J. R. R. Tolkien. Ransom Riggs uses several Old English words, such as syndrigast (singular, peculiar), ymbryne (period, cycle), etc., dubbed as "Old Peculiar" ones.

A number of websites devoted to Modern Paganism and historical reenactment offer reference material and forums promoting the active use of Old English. There is also an Old English version of Wikipedia. However, one investigation found that many Neo-Old English texts published online bear little resemblance to the historical language and have many basic grammatical mistakes.