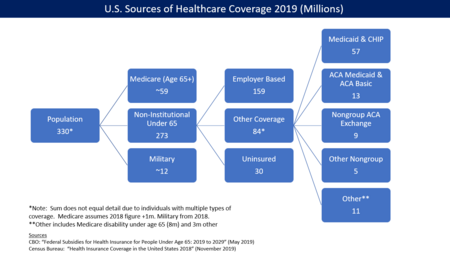

In the United States, health insurance coverage is provided by several public and private sources. During 2019, the U.S. population overall was approximately 330 million, with 59 million people 65 years of age and over covered by the federal Medicare program. The 273 million non-institutionalized persons under age 65 either obtained their coverage from employer-based (159 million) or non-employer based (84 million) sources, or were uninsured (30 million). During the year 2019, 89% of the non-institutionalized population had health insurance coverage. Separately, approximately 12 million military personnel (considered part of the "institutional" population) received coverage through the Veteran's Administration and Military Health System.

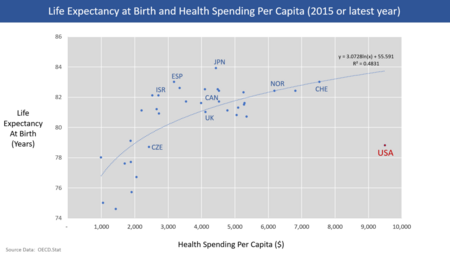

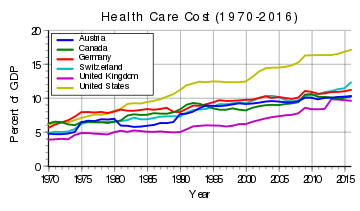

Despite being among the top world economic powers, the US remains the sole industrialized nation in the world without universal health care coverage.

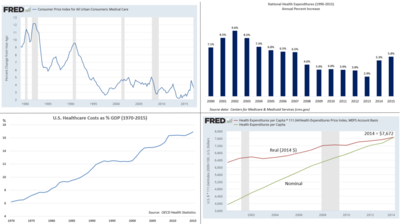

Prohibitively high cost is the primary reason Americans give for problems accessing health care. At approximately 30 million in 2019, higher than the entire population of Australia, the number of people without health insurance coverage in the United States is one of the primary concerns raised by advocates of health care reform. Lack of health insurance is associated with increased mortality, in the range 30-90 thousand deaths per year, depending on the study.

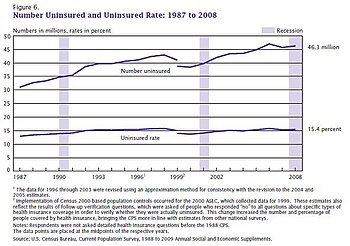

Multiple surveys indicate the number of uninsured fell between 2013 and 2016 due to expanded Medicaid eligibility and health insurance exchanges established due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as the "ACA" or "Obamacare". According to the United States Census Bureau, in 2012 there were 45.6 million people in the US (14.8% of the under-65 population) who were without health insurance. Following the implementation of major ACA provisions in 2013, this figure fell by 18.3 million or 40%, to 27.3 million by 2016 or 8.6% of the under-65 population.

However, the improvement in coverage began to reverse under President Trump. The Census Bureau reported that the number of uninsured persons rose from 27.3 million in 2016 to 29.6 million in 2019, up 2.3 million or 8%. The uninsured rate rose from 8.6% in 2016 to 9.2% in 2019. The 2017 increase was the first increase in the number and rate of uninsured since 2010. Further, the Commonwealth Fund estimated in May 2018 that the number of uninsured increased by 4 million from early 2016 to early 2018. The rate of those uninsured increased from 12.7% in 2016 to 15.5% under their methodology. The impact was greater among lower-income adults, who had a higher uninsured rate than higher-income adults. Regionally, the South and West had higher uninsured rates than the North and East. CBO forecast in May 2019 that 6 million more would be without health insurance in 2021 under Trump's policies (33 million), relative to continuation of Obama policies (27 million).

The causes of this rate of uninsurance remain a matter of political debate. In 2018, states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA had an uninsured rate that averaged 8%, about half the rate of those states that did not (15%). Nearly half those without insurance cite its cost as the primary factor. Rising insurance costs have contributed to a trend in which fewer employers are offering health insurance, and many employers are managing costs by requiring higher employee contributions. Many of the uninsured are the working poor or are unemployed.

Overview

Health insurance coverage is provided by several public and private sources in the United States. Analyzing these statistics is more challenging due to multiple survey methods and persons with multiple sources of insurance, such as those with coverage under both an employer plan and Medicaid.

For the 273 million non-institutional persons under age 65 in 2019:

- There were 159 million with employer-based coverage, 84 million with other coverage, and 30 million uninsured.

- Of the 159 million with employer-based coverage, many are in self-funded health plans - about 60% in 2017

- Of the 84 million with other coverage, 57 million were covered by Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), 12 million were covered by the ACA Medicaid expansion, 9 million were covered by the ACA/Obamacare exchanges, 5 million had other coverage such as private insurance purchased outside the ACA exchanges, and 1 million were covered by the ACA Basic Health Program.

- Of the 9 million on the ACA exchanges, 8 million received subsidies and 1 million did not.

- Of the 30 million uninsured, 24 million (80%) were lawfully present while 6 million (20%) were not lawfully present (i.e., undocumented immigrants).

- In 2018, 41% of the uninsured were white, 37% were Hispanic, and 14% were black.

- Approximately 12 million institutional (military) personnel were covered by the Veteran's Administration in 2018.

- The uninsured rate fell from a peak of 18.2% in 2010 to 10.5% by 2015, due primarily to ACA/Obamacare along with improvements in the economy.

- States that expanded Medicaid under Obamacare (37 as of 2019, including Washington D.C.) had lower uninsured rates than states that did not.

- Inability to afford insurance was the primary reason cited by persons without coverage (46%).

- Lack of health insurance is associated with increased mortality, in the range 30-90 thousand deaths per year, depending on the study. This figure is calculated based on 1 additional death per 300-800 persons without health insurance, on a base of 27 million uninsured persons.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports the number and percentage of uninsured during each year. The following table includes those under age 65 who were uninsured at the time of interview.

| Year | Number Uninsured (Mil) | Uninsured Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 48.2 | 18.2% |

| 2013 (Pre-ACA) | 44.3 | 16.6% |

| 2016 | 28.2 | 10.4% |

| 2017 | 28.9 | 10.7% |

| 2018 | 30.1 | 11.1% |

| 2019 | 32.8 | 12.1% |

| 2020 | 31.2 | 11.5% |

| 2021 | 29.6 | 11.0% |

| 2022H | 27.0 | 9.9% |

The 2010 figure represents the most recent peak, which was driven upward by the Great Recession. Most of the major provisions of the ACA took effect in 2014, so 2013 reflects the pre-ACA level. After reaching a record low in 2016 at the end of the Obama Administration, the number and percent of uninsured has risen during the first two years of the Trump Administration. The New York Times reported in January 2019 that the Trump Administration has taken a variety of steps to weaken the ACA, adversely affecting coverage. The increases in the number of uninsured in the first 3 years of the Trump administration (2017-2019) reversed in 2020-2021, as Coronavirus relief measures expanded eligibility and reduced costs.

Estimates of the number of uninsured

Several public and private sources report the number and percentage of the uninsured. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported the actual number of uninsured at 28.3 million in 2015, 27.5 million in 2016, 27.8 million in 2017, and 28.9 million in 2018. The CBO May 2019 ten-year forecast reflected the policies of the Trump administration and estimated the number of uninsured would rise from 30 million in 2019, to 34 million by 2026, and to 35 million by 2029. In a previous March 2016 ten-year forecast reflecting the policies of the Obama administration, CBO forecast 27 million uninsured in 2019 and 28 million in 2026. The primary reason for the 6.5 million (24%) increase in uninsured from 2016 to 2029 is the repeal of the ACA individual mandate to have health insurance, enacted as part of the Trump tax cuts, with people not obtaining comprehensive insurance in the absence of a mandate or due to higher insurance costs.

Gallup estimated in July 2014 that the uninsured rate for adults (persons 18 years of age and over) was 13.4% as of Q2 2014, down from 18.0% in Q3 2013 when the health insurance exchanges created under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA or "Obamacare") first opened. The uninsured rate fell across nearly all demographic groups.

The Commonwealth Fund reported that the uninsured rate among adults 19-64 declined from 20% in Q3 2013 to 15% in Q2 2014, meaning approximately 9.5 million more adults had health insurance.

The United States Census Bureau annually reports statistics on the uninsured. The 2018 Census Bureau Health Insurance highlights summary report states that:

- "In 2018, 8.5 percent of people, or 27.5 million, did not have health insurance at any point during the year. The uninsured rate and number of uninsured increased from 2017 (7.9 percent or 25.6 million).

- The percentage of people with health insurance coverage for all or part of 2018 was 91.5 percent, lower than the rate in 2017 (92.1 percent). Between 2017 and 2018, the percentage of people with public coverage decreased 0.4 percentage points, and the percentage of people with private coverage did not statistically change.

- In 2018, private health insurance coverage continued to be more prevalent than public coverage, covering 67.3 percent of the population and 34.4 percent of the population, respectively. Of the subtypes of health insurance coverage, employer-based insurance remained the most common, covering 55.1 percent of the population for all or part of the calendar year.

- Between 2017 and 2018, the percentage of people covered by Medicaid decreased by 0.7 percentage points to 17.9 percent. The rate of Medicare coverage increased by 0.4 percentage points. The percentage of people with employment-based coverage, direct-purchase coverage, TRICARE, and VA or CHAMPVA health care did not statistically change between 2017 and 2018.

- The percentage of uninsured children under the age of 19 increased by 0.6 percentage points between 2017 and 2018, to 5.5 percent.

- Between 2017 and 2018, the percentage of people without health insurance coverage at the time of interview decreased in three states and increased in eight states."

Underinsured

Those who are insured may be underinsured such that they cannot afford adequate medical care. A 2003 estimated that 16 million U.S. adults were underinsured in 2003, disproportionately affecting those with lower incomes – 73% of the underinsured in the study population had annual incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.

In 2019 Gallup found that 25% of U.S. adults said they or a family member had delayed treatment for a serious medical condition during the year because of cost, up from 12% in 2003 and 19% in 2015. For any condition, 33% reported delaying treatment, up from 24% in 2003 and 31% in 2015.

Coverage gaps also occur among the insured population. Johns Hopkins University professor Vicente Navarro stated in 2003, "the problem does not end here, with the uninsured. An even larger problem is the underinsured" and "The most credible estimate of the number of people in the United States who have died because of lack of medical care was provided by a study carried out by Harvard Medical School Professors Himmelstein and Woolhandler. They concluded that almost 100,000 people died in the U.S. yearly because of lack of needed care." Another study focusing on the effect of being uninsured found that individuals with private insurance were less likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer than either the uninsured or Medicaid beneficiaries. A study examining the effects of health insurance cost-sharing more generally found that chronically ill patients with higher co-payments sought less care for both minor and serious symptoms while no effect on self-reported health status was observed. The authors concluded that the effect of cost sharing should be carefully monitored.

Coverage gaps and affordability also surfaced in a 2007 international comparison by the Commonwealth Fund. Among adults surveyed in the U.S., 37% reported that they had foregone needed medical care in the previous year because of cost; either skipping medications, avoiding seeing a doctor when sick, or avoiding other recommended care. The rate was higher – 42% –, among those with chronic conditions. The study reported that these rates were well above those found in the other six countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the UK. The study also found that 19% of U.S. adults surveyed reported serious problems paying medical bills, more than double the rate in the next highest country.

Coverage trends under President Trump

Gains in healthcare coverage under President Obama began to reverse under President Trump. The CDC reported that the number of uninsured rose from 28.2 million in 2016 (the last year of the Obama Administration) to 32.8 million in 2019, an increase of 4.6 million or 16%.

The Commonwealth Fund estimated in May 2018 that the number of uninsured increased by 4 million from early 2016 to early 2018. The rate of those uninsured increased from 12.7% in 2016 to 15.5%. This was due to two factors: 1) Not addressing specific weaknesses in the ACA; and 2) Actions by the Trump administration that exacerbated those weaknesses. The impact was greater among lower-income adults, who had a higher uninsured rate than higher-income adults. Regionally, the South and West had higher uninsured rates than the North and East. Further, those 18 states that have not expanded Medicaid had a higher uninsured rate than those that did.

Approximately 5.4 million Americans lost their health insurance from February to May 2020 after losing their jobs during the COVID-19 recession. The Independent reported that Families USA report "found that the spike in uninsured Americans – adding to an estimated 84 million people who are already uninsured or underinsured – is 39 per cent higher than any previous annual increase, including the most recent surge at the height of the recession between 2008 and 2009 when nearly 4 million non-elderly Americans lost insurance."

Uninsured demographic

The Kaiser Family Foundation reported in October 2016 that there were 27.2 million uninsured under age 65, roughly 10% of the 272 million persons in that group. Kaiser reported that:

- 2.6 million were in the "coverage gap" due to the 19 states that chose not to expand the Medicaid program under the ACA/Obamacare, meaning their income was above the Medicaid eligibility limit but below the threshold for subsidies on the ACA exchanges (~44% to 100% of the federal poverty level or FPL);

- 5.4 million were undocumented immigrants;

- 4.5 million had an employer's insurance offer (making them ineligible for ACA/Obamacare coverage) but declined it;

- 3.0 million were ineligible for financial assistance under ACA/Obamacare due to sufficiently high income;

- 6.4 million were eligible for Medicaid or other public healthcare program but did not pursue it; and

- 5.3 million were eligible for ACA/Obamacare tax credits but did not enroll in the program.

- An estimated 46% cited costs as a barrier to getting insurance coverage.

- Nearly 12 million (43%) of persons were eligible for financial assistance (Medicaid or ACA subsidies) but did not enroll to obtain it.

As of 2017, Texas had the highest number of uninsured at 17%, followed by Oklahoma, Alaska, and Georgia.

Uninsured children and young adults

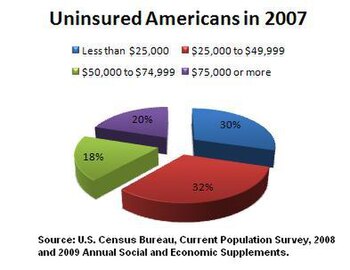

In 2009 the Census Bureau states that 10.0 percent or 7.5 million children under the age of 18 were medically uninsured. Children living in poverty are 15.1 percent more likely than other children to be uninsured. The lower the income of a household the more likely it is they are uninsured. In 2009, a household with an annual income of 25,000 or less was only 26.6 percent likely not to have medical insurance and those with an annual income of 75,000 or more were only 9.1 percent unlikely to be insured. According to the Census Bureau, in 2007, there were 8.1 million uninsured children in the US. Nearly 8 million young adults (those aged 18–24), were uninsured, representing 28.1% of their population. Young adults make up the largest age segment of the uninsured, are the most likely to be uninsured, and are one of the fastest growing segments of the uninsured population. They often lose coverage under their parents' health insurance policies or public programs when they reach age 19. Others lose coverage when they graduate from college. Many young adults do not have the kind of stable employment that would provide ongoing access to health insurance. According to the Congressional Budget Office the plan the way it is now would have to cover unmarried dependents under their parents' insurance up to age 26. These changes also affect large employers, including self-insured firms, so that the firm bears the financial responsibility of providing coverage. The only exception to this is policies that were maintained continuously before the enactment of this legislation. Those policies would be grandfathered in.

Non-citizens

Non-citizens are more likely to be uninsured than citizens, with a 43.8% uninsured rate. This is attributable to a higher likelihood of working in a low-wage job that does not offer health benefits, and restrictions on eligibility for public programs. The longer a non-citizen immigrant has been in the country, the less likely they are to be uninsured. In 2006, roughly 27% of immigrants entering the country before 1970 were uninsured, compared to 45% of immigrants entering the country in the 1980s and 49% of those entering between 2000 and 2006.

Most uninsured non-citizens are recent immigrants; almost half entered the country between 2000 and 2006, and 36% entered during the 1990s. Foreign-born non-citizens accounted for over 40% of the increase in the uninsured between 1990 and 1998, and over 90% of the increase between 1998 and 2003. One reason for the acceleration after 1998 may be restrictions imposed by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996. Almost seven out of ten (68%) of uninsured non-citizens live in California, Texas, Florida, or New York.

Downturn effects

A report by the Kaiser Family Foundation in April 2008 found that US economic downturns place a significant strain on state Medicaid and SCHIP programs. The authors estimated that a 1% increase in the unemployment rate increase Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment by 1 million, and increase the number uninsured by 1.1 million. State spending on Medicaid and SCHIP would increase by $1.4 billion (total spending on these programs would increase by $3.4 billion). This increased spending would occur while state government revenues were declining. During the last downturn, the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA) included federal assistance to states, which helped states avoid tightening their Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility rules. The authors conclude that Congress should consider similar relief for the current economic downturn.

History

Prior to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, medical underwriting was common, but after the law came into effect in 2014 it became effectively prohibited.

Medical underwriting made difficult for many consumers to purchase coverage on the individual market. Medical underwriting meant that insurance companies screen applicants for pre-existing conditions and reject those with serious conditions such as arthritis, cancer, and heart disease, but also such common ailments as acne, being 20 pounds over or under weight, and old sports injuries. In 2008, an estimated 5 million of those without health insurance were considered "uninsurable" because of pre-existing conditions.

Proponents of medical underwriting argue that it ensures that individual health insurance premiums are kept as low as possible. Critics of medical underwriting believe that it unfairly prevents people with relatively minor and treatable pre-existing conditions from obtaining health insurance.

One large industry survey found that 13% of applicants for individual health insurance who went through medical underwriting were denied coverage in 2004. Declination rates increased significantly with age, rising from 5% for those under 18 to just under one-third for those aged 60 to 64. Among those who were offered coverage, the study found that 76% received offers at standard premium rates, and 22% were offered higher rates. The frequency of increased premiums also increased with age, so for applicants over 40, roughly half were affected by medical underwriting, either in the form of denial or increased premiums. In contrast, almost 90% of applicants in their 20s were offered coverage, and three-quarters of those were offered standard rates. Seventy percent of applicants age 60–64 were offered coverage, but almost half the time (40%) it was at an increased premium. The study did not address how many applicants who were offered coverage at increased rates chose to decline the policy. A study conducted by the Commonwealth Fund in 2001 found that, among those aged 19 to 64 who sought individual health insurance during the previous three years, the majority found it unaffordable, and less than a third ended up purchasing insurance. This study did not distinguish between consumers who were quoted increased rates due to medical underwriting and those who qualified for standard or preferred premiums. Some states have outlawed medical underwriting as a prerequisite for individually purchased health coverage. These states tend to have the highest premiums for individual health insurance.

Causes

Americans who are uninsured may be so because their job does not offer insurance; they are unemployed and cannot pay for insurance; or they may be financially able to buy insurance but consider the cost prohibitive. During 2009 the continued low employment rate has negatively affected those who had previously been enrolled in employment-based insurance policies. Census Bureau states a 55 percent drop. Other uninsured Americans have chosen to join a health care sharing ministry as an alternative to insurance.

Low-income workers are less likely than higher income individuals to be offered coverage by their employer (or by their spouse's employer) and less able to afford buying it on their own. Beginning with wage and price controls during World War II, and cemented by an income tax exemption ruling in 1954, most working Americans have received their health insurance from their employers. However, recent trends have shown an ongoing decline in employer-sponsored health insurance benefits. In 2000, 68% of small companies with 3 to 199 workers offered health benefits. Since that time, that number has continued to drop to 2007, when 59% offered health benefits. For large firms with 200 or more workers, in 2000, 99% of employers offered health benefits; in 2007, that number stayed the same. On average, considering firms of all numbers of employees, in 2000, 69% offered health insurance, and that number has fallen nearly every year since, to 2007, when 60% of employers offered health insurance.

One study published in 2008 found that people of average health are least likely to become uninsured if they have large group health coverage, more likely to become uninsured if they have small group coverage, and most likely to become uninsured if they have individual health insurance. But, "for people in poor or fair health, the chances of losing coverage are much greater for people who had small-group insurance than for those who had individual insurance." The authors attribute these results to the combination in the individual market of high costs and guaranteed renewability of coverage. Individual coverage costs more if it is purchased after a person becomes unhealthy but "provides better protection (compared to group insurance) against high premiums for already individually insured people who become high risk." Healthy individuals are more likely to drop individual coverage than less-expensive, subsidized employment-based coverage, but group coverage leaves them "more vulnerable to dropping or losing any and all coverage than does individual insurance" if they become seriously ill.

Roughly a quarter of the uninsured are eligible for public coverage but are not enrolled. Possible reasons include a lack of awareness of the programs or of how to enroll, reluctance due to a perceived stigma associated with public coverage, poor retention of enrollees, and burdensome administrative procedures. In addition, some state programs have enrollment caps.

A study by the Kaiser Family Foundation published in June 2009 found that 45% of low-income adults under age 65 lack health insurance. Almost a third of non-elderly adults are low income, with family incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level. Low-income adults are generally younger, less well educated, and less likely to live in a household with a full-time worker than are higher income adults; these factors contribute to the likelihood of being uninsured. In addition, the chances of being healthy decline with lower income; 19% of adults with incomes below the federal poverty level describe their health as fair or poor.

Consequences

Insurance coverage helps save lives, by encouraging early detection and prevention of dangerous medical conditions. According to a 2014 study, the ACA likely prevented an estimated 50,000 preventable patient deaths from 2010 to 2013. City University public health professors David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler wrote in January 2017 that a rollback of the ACA's Medicaid expansion alone would cause an estimated 43,956 deaths annually.

The Federal Reserve publishes data on premature death rates by county, defined as those dying below age 74. According to the Kaiser Foundation, expanding Medicaid in the remaining 19 states would cover up to 4.5 million persons, thus reducing mortality. Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Missouri and South Carolina, indicated on the Federal Reserve map (see graph at right) as having many counties with high premature mortality rates, did not expand Medicaid.

A study published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2009 found that lack of health insurance is associated with about 45,000 excess preventable deaths per year. One of the authors characterized the results as "now one dies every 12 minutes." Since then, as the number of uninsured has risen from about 46 million in 2009 to 48.6 million in 2012, the number of preventable deaths due to lack of insurance has grown to about 48,000 per year.

A survey released in 2008 found that being uninsured impacts American consumers' health in the following ways:

- More of the uninsured chose not to see a doctor when were sick or hurt (53%) vs 46% of the insured.

- Fewer of the uninsured (28%) report currently undergoing treatment or participating in a program to help them manage a chronic condition; 37% of the insured are receiving such treatment.

- 21% of the uninsured, vs. 16% of the insured, believe their overall health is below average for people in their age group.

Cost shifting

The costs of treating the uninsured must often be absorbed by providers as charity care, passed on to the insured via cost-shifting and higher health insurance premiums, or paid by taxpayers through higher taxes.

On the other hand, the uninsured often subsidize the insured because the uninsured use fewer services and are often billed at a higher rate. A study found that in 2009, uninsured patients presenting in U.S. emergency departments were less likely to be admitted for inpatient care than those with Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance. 60 Minutes reported, "Hospitals charge uninsured patients two, three, four or more times what an insurance company would pay for the same treatment." On average, per capita health care spending on behalf of the uninsured is a bit more than half that for the insured.

Hospitals and other providers are reimbursed for the cost of providing uncompensated care via a federal matching fund program. Each state enacts legislation governing the reimbursement of funds to providers. In Missouri, for example, providers assessments totaling $800 million are matched – $2 for each assessed $1 – to create a pool of approximately $2 billion. By federal law these funds are transferred to the Missouri Hospital Association for disbursement to hospitals for the costs incurred providing uncompensated care including Disproportionate Share Payments (to hospitals with high quantities of uninsured patients), Medicaid shortfalls, Medicaid managed care payments to insurance companies and other costs incurred by hospitals. In New Hampshire, by statute, reimbursable uncompensated care costs shall include: charity care costs, any portion of Medicaid patient care costs that are unreimbursed by Medicaid payments, and any portion of bad debt costs that the commissioner determines would meet the criteria under 42 U.S.C. section 1396r-4(g) governing hospital-specific limits on disproportionate share hospital payments under Title XIX of the Social Security Act.

A study published in August 2008 in Health Affairs found that covering all of the uninsured in the US would increase national spending on health care by $122.6 billion, which would represent a 5% increase in health care spending and 0.8% of GDP. "From society’s perspective, covering the uninsured is still a good investment. Failure to act in the near term will only make it more expensive to cover the uninsured in the future, while adding to the amount of lost productivity from not insuring all Americans," said Professor Jack Hadley, the study's lead author. The impact on government spending could be higher, depending on the details of the plan used to increase coverage and the extent to which new public coverage crowded out existing private coverage.

Over 60% of personal bankruptcies is caused by medical bills. Most of these persons had medical insurance.

Effects on health of the uninsured

From 2000 to 2004, the Institute of Medicine's Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance issued a series of six reports that reviewed and reported on the evidence on the effects of the lack of health insurance coverage.

The reports concluded that the committee recommended that the nation should implement a strategy to achieve universal health insurance coverage. As of 2011, a comprehensive national plan to address what universal health plan supporters terms "America's uninsured crisis", has yet to be enacted. A few states have achieved progress towards the goal of universal health insurance coverage, such as Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont, but other states including California, have failed attempts of reforms.

The six reports created by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found that the principal consequences of uninsurance were the following: Children and Adults without health insurance did not receive needed medical care; they typically live in poorer health and die earlier than children or adults who have insurance. The financial stability of a whole family can be put at risk if only one person is uninsured and needs treatment for unexpected health care costs. The overall health status of a community can be adversely affected by a higher percentage of uninsured people within the community. The coverage gap between the insured and the uninsured has not decreased even after the recent federal initiatives to extend health insurance coverage.

The last report was published in 2004 and was named Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations. This report recommended the following: The President and Congress need to develop a strategy to achieve universal insurance coverage and establish a firm schedule to reach this goal by the year 2010. The committee also recommended that the federal and state governments provide sufficient resources for Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) to cover all persons currently eligible until the universal coverage takes effect. They also warned that the federal and state governments should prevent the erosion of outreach efforts, eligibility, enrollment, and coverage of these specific programs.

Some people think that not having health insurance will have adverse consequences for the health of the uninsured. On the other hand, some people believe that children and adults without health insurance have access to needed health care services at hospital emergency rooms, community health centers, or other safety net facilities offering charity care. Some observers note that there is a solid body of evidence showing that a substantial proportion of U.S. health care expenditures is directed toward care that is not effective and may sometimes even be harmful. At least for the insured population, spending more and using more health care services does not always yield better health outcomes or increase life expectancy.

Children in America are typically perceived as in good health relative to adults, due to the fact that most serious health problems occur later in one's life. Certain conditions including asthma, diabetes, and obesity have become much more prevalent among children in the past few decades. There is also a growing population of vulnerable children with special health care needs that require ongoing medical attention, which would not be accessible without health insurance. More than 10 million children in the United States meet the federal definition of children with special health care needs "who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, development, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally". These children require health related services of an amount beyond that required by the average children in America. Typically when children acquire health insurance, they are much less likely to experience previously unmet health care needs, this includes the average child in America and children with special health care needs. The Committee on Health Insurance Status and Its Consequences concluded that the effects of health insurance on children's health outcomes: Children with health insurance receive more timely diagnosis of serious health conditions, experience fewer hospitalizations, and miss fewer days of school.

The same committee analyzed the effects of health insurance on adult's health outcomes: adults who do not have health insurance coverage who acquire Medicare coverage at age 65, experience substantially improved health and functional status, particularly those who have cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Adults who have cardiovascular disease or other cardiac risk factors that are uninsured are less likely to be aware of their condition, which leads to worse health outcomes for those individuals. Without health insurance, adults are more likely to be diagnosed with certain cancers that would have been detectable earlier by screening by a clinician if they had regularly visited a doctor. As a consequence, these adults are more likely to die from their diagnosed cancer or suffer poorer health outcomes.

Many towns and cities in the United States have high concentrations of people under the age of 65 who lack health insurance. There are implications of high rates of uninsurance for communities and for insured people in those communities. Institute of Medicine committee warned of the potential problems of high rates of uninsurance for local health care, including reduced access to clinic-based primary care, specialty services, and hospital-based emergency services.

Excess deaths due to 2017-2019 coverage losses

In October 2020, Health Affairs writers summarized the results of several studies that placed the higher death rates for the uninsured between 1 per 278 to 1 per 830 persons without insurance: "Based on the ACS coverage data, we estimate that between 3,399 and 10,147 excess deaths among non-elderly US adults may have occurred over the 2017-2019 time period due to coverage losses during these years. Using the NHIS figures for coverage losses yields a higher estimate (between 8,434 and 25,180 non-elderly adult deaths attributable to coverage losses), while the CPS figures yield an estimate of 3,528-10,532 excess deaths among non-elderly adults. These figures do not completely capture the population effects of coverage loss, as they exclude the excess deaths that would likely result from coverage losses among children. In 2020 and beyond, we can project even more loss of life if, as expected, millions more lose health coverage due to the economic downturn associated with the pandemic."

Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

EMTALA, enacted by the federal government in 1986, requires that hospital emergency departments treat emergency conditions of all patients regardless of their ability to pay and is considered a critical element in the "safety net" for the uninsured. However, the federal law established no direct payment mechanism for such care. Indirect payments and reimbursements through federal and state government programs have never fully compensated public and private hospitals for the full cost of care mandated by EMTALA. In fact, more than half of all emergency care in the U.S. now goes uncompensated. According to some analyses, EMTALA is an unfunded mandate that has contributed to financial pressures on hospitals in the last 20 years, causing them to consolidate and close facilities, and contributing to emergency room overcrowding. According to the Institute of Medicine, between 1993 and 2003, emergency room visits in the U.S. grew by 26%, while in the same period, the number of emergency departments declined by 425. Hospitals bill uninsured patients directly under the fee-for-service model, often charging much more than insurers would pay, and patients may become bankrupt when hospitals file lawsuits to collect.

Mentally ill patients present a unique challenge for emergency departments and hospitals. In accordance with EMTALA, mentally ill patients who enter emergency rooms are evaluated for emergency medical conditions. Once mentally ill patients are medically stable, regional mental health agencies are contacted to evaluate them. Patients are evaluated as to whether they are a danger to themselves or others. Those meeting this criterion are admitted to a mental health facility to be further evaluated by a psychiatrist. Typically, mentally ill patients can be held for up to 72 hours, after which a court order is required.