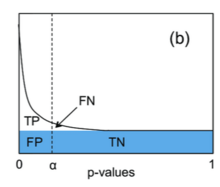

In statistics, the false discovery rate (FDR) is a method of conceptualizing the rate of type I errors in null hypothesis testing when conducting multiple comparisons. FDR-controlling procedures are designed to control the FDR, which is the expected proportion of "discoveries" (rejected null hypotheses) that are false (incorrect rejections of the null). Equivalently, the FDR is the expected ratio of the number of false positive classifications (false discoveries) to the total number of positive classifications (rejections of the null). The total number of rejections of the null include both the number of false positives (FP) and true positives (TP). Simply put, FDR = FP / (FP + TP). FDR-controlling procedures provide less stringent control of Type I errors compared to family-wise error rate (FWER) controlling procedures (such as the Bonferroni correction), which control the probability of at least one Type I error. Thus, FDR-controlling procedures have greater power, at the cost of increased numbers of Type I errors.

History

Technological motivations

The modern widespread use of the FDR is believed to stem from, and be motivated by, the development in technologies that allowed the collection and analysis of a large number of distinct variables in several individuals (e.g., the expression level of each of 10,000 different genes in 100 different persons). By the late 1980s and 1990s, the development of "high-throughput" sciences, such as genomics, allowed for rapid data acquisition. This, coupled with the growth in computing power, made it possible to seamlessly perform a very high number of statistical tests on a given data set. The technology of microarrays was a prototypical example, as it enabled thousands of genes to be tested simultaneously for differential expression between two biological conditions.

As high-throughput technologies became common, technological and/or financial constraints led researchers to collect datasets with relatively small sample sizes (e.g. few individuals being tested) and large numbers of variables being measured per sample (e.g. thousands of gene expression levels). In these datasets, too few of the measured variables showed statistical significance after classic correction for multiple tests with standard multiple comparison procedures. This created a need within many scientific communities to abandon FWER and unadjusted multiple hypothesis testing for other ways to highlight and rank in publications those variables showing marked effects across individuals or treatments that would otherwise be dismissed as non-significant after standard correction for multiple tests. In response to this, a variety of error rates have been proposed—and become commonly used in publications—that are less conservative than FWER in flagging possibly noteworthy observations. The FDR is useful when researchers are looking for "discoveries" that will give them followup work (E.g.: detecting promising genes for followup studies), and are interested in controlling the proportion of "false leads" they are willing to accept.

Literature

The FDR concept was formally described by Yoav Benjamini and Yosef Hochberg in 1995 (BH procedure) as a less conservative and arguably more appropriate approach for identifying the important few from the trivial many effects tested. The FDR has been particularly influential, as it was the first alternative to the FWER to gain broad acceptance in many scientific fields (especially in the life sciences, from genetics to biochemistry, oncology and plant sciences). In 2005, the Benjamini and Hochberg paper from 1995 was identified as one of the 25 most-cited statistical papers.

Prior to the 1995 introduction of the FDR concept, various precursor ideas had been considered in the statistics literature. In 1979, Holm proposed the Holm procedure, a stepwise algorithm for controlling the FWER that is at least as powerful as the well-known Bonferroni adjustment. This stepwise algorithm sorts the p-values and sequentially rejects the hypotheses starting from the smallest p-values.

Benjamini (2010) said that the false discovery rate, and the paper Benjamini and Hochberg (1995), had its origins in two papers concerned with multiple testing:

- The first paper is by Schweder and Spjotvoll (1982) who suggested plotting the ranked p-values and assessing the number of true null hypotheses () via an eye-fitted line starting from the largest p-values. The p-values that deviate from this straight line then should correspond to the false null hypotheses. This idea was later developed into an algorithm and incorporated the estimation of into procedures such as Bonferroni, Holm or Hochberg. This idea is closely related to the graphical interpretation of the BH procedure.

- The second paper is by Branko Soric (1989) which introduced the terminology of "discovery" in the multiple hypothesis testing context. Soric used the expected number of false discoveries divided by the number of discoveries as a warning that "a large part of statistical discoveries may be wrong". This led Benjamini and Hochberg to the idea that a similar error rate, rather than being merely a warning, can serve as a worthy goal to control.

The BH procedure was proven to control the FDR for independent tests in 1995 by Benjamini and Hochberg. In 1986, R. J. Simes offered the same procedure as the "Simes procedure", in order to control the FWER in the weak sense (under the intersection null hypothesis) when the statistics are independent.

Definitions

Based on definitions below we can define Q as the proportion of false discoveries among the discoveries (rejections of the null hypothesis):

- .

where is the number of false discoveries and is the number of true discoveries.

The false discovery rate (FDR) is then simply:

where is the expected value of . The goal is to keep FDR below a given threshold q. To avoid division by zero, is defined to be 0 when . Formally, .

Classification of multiple hypothesis tests

The following table defines the possible outcomes when testing multiple null hypotheses. Suppose we have a number m of null hypotheses, denoted by: H1, H2, ..., Hm. Using a statistical test, we reject the null hypothesis if the test is declared significant. We do not reject the null hypothesis if the test is non-significant. Summing each type of outcome over all Hi yields the following random variables:

|

|

Null hypothesis is true (H0) | Alternative hypothesis is true (HA) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test is declared significant | V | S | R |

| Test is declared non-significant | U | T | |

| Total | m |

- m is the total number hypotheses tested

- is the number of true null hypotheses, an unknown parameter

- is the number of true alternative hypotheses

- V is the number of false positives (Type I error) (also called "false discoveries")

- S is the number of true positives (also called "true discoveries")

- T is the number of false negatives (Type II error)

- U is the number of true negatives

- is the number of rejected null hypotheses (also called "discoveries", either true or false)

In m hypothesis tests of which are true null hypotheses, R is an observable random variable, and S, T, U, and V are unobservable random variables.

Controlling procedures

The settings for many procedures is such that we have null hypotheses tested and their corresponding p-values. We list these p-values in ascending order and denote them by . A procedure that goes from a small test-statistic to a large one will be called a step-up procedure. In a similar way, in a "step-down" procedure we move from a large corresponding test statistic to a smaller one.

Benjamini–Hochberg procedure

The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (BH step-up procedure) controls the FDR at level . It works as follows:

- For a given , find the largest k such that

- Reject the null hypothesis (i.e., declare discoveries) for all for

Geometrically, this corresponds to plotting vs. k (on the y and x axes respectively), drawing the line through the origin with slope , and declaring discoveries for all points on the left, up to, and including the last point that is below the line.

The BH procedure is valid when the m tests are independent, and also in various scenarios of dependence, but is not universally valid. It also satisfies the inequality:

If an estimator of is inserted into the BH procedure, it is no longer guaranteed to achieve FDR control at the desired level. Adjustments may be needed in the estimator and several modifications have been proposed.

Note that the mean for these m tests is , the Mean(FDR ) or MFDR, adjusted for m independent or positively correlated tests (see AFDR below). The MFDR expression here is for a single recomputed value of and is not part of the Benjamini and Hochberg method.

Benjamini–Yekutieli procedure

The Benjamini–Yekutieli procedure controls the false discovery rate under arbitrary dependence assumptions. This refinement modifies the threshold and finds the largest k such that:

- If the tests are independent or positively correlated (as in Benjamini–Hochberg procedure):

- Under arbitrary dependence (including the case of negative correlation), c(m) is the harmonic number: .

- Note that can be approximated by using the Taylor series expansion and the Euler–Mascheroni constant ():

Using MFDR and formulas above, an adjusted MFDR (or AFDR) is the minimum of the mean for m dependent tests, i.e., . Another way to address dependence is by bootstrapping and rerandomization.

Storey-Tibshirani procedure

In the Storey-Tibshirani procedure, q-values are used for controlling the FDR.

Properties

Adaptive and scalable

Using a multiplicity procedure that controls the FDR criterion is adaptive and scalable. Meaning that controlling the FDR can be very permissive (if the data justify it), or conservative (acting close to control of FWER for sparse problem) - all depending on the number of hypotheses tested and the level of significance.

The FDR criterion adapts so that the same number of false discoveries (V) will have different implications, depending on the total number of discoveries (R). This contrasts with the family-wise error rate criterion. For example, if inspecting 100 hypotheses (say, 100 genetic mutations or SNPs for association with some phenotype in some population):

- If we make 4 discoveries (R), having 2 of them be false discoveries (V) is often very costly. Whereas,

- If we make 50 discoveries (R), having 2 of them be false discoveries (V) is often not very costly.

The FDR criterion is scalable in that the same proportion of false discoveries out of the total number of discoveries (Q), remains sensible for different number of total discoveries (R). For example:

- If we make 100 discoveries (R), having 5 of them be false discoveries () may not be very costly.

- Similarly, if we make 1000 discoveries (R), having 50 of them be false discoveries (as before, ) may still not be very costly.

Dependency among the test statistics

Controlling the FDR using the linear step-up BH procedure, at level q, has several properties related to the dependency structure between the test statistics of the m null hypotheses that are being corrected for. If the test statistics are:

- Independent:

- Independent and continuous:

- Positive dependent:

- In the general case: , where is the Euler–Mascheroni constant.

Proportion of true hypotheses

If all of the null hypotheses are true (), then controlling the FDR at level q guarantees control over the FWER (this is also called "weak control of the FWER"): , simply because the event of rejecting at least one true null hypothesis is exactly the event , and the event is exactly the event (when , by definition). But if there are some true discoveries to be made () then FWER ≥ FDR. In that case there will be room for improving detection power. It also means that any procedure that controls the FWER will also control the FDR.

Average power

The average power of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure can be computed analytically

Related concepts

The discovery of the FDR was preceded and followed by many other types of error rates. These include:

- PCER (per-comparison error rate) is defined as: . Testing individually each hypothesis at level α guarantees that (this is testing without any correction for multiplicity)

- FWER (the family-wise error rate) is defined as: . There are numerous procedures that control the FWER.

- (The tail probability of the False Discovery Proportion), suggested by Lehmann and Romano, van der Laan at al, is defined as: .

- (also called the generalized FDR by Sarkar in 2007) is defined as: .

- is the proportion of false discoveries among the discoveries", suggested by Soric in 1989, and is defined as: . This is a mixture of expectations and realizations, and has the problem of control for .

- (or Fdr) was used by Benjamini and Hochberg, and later called "Fdr" by Efron (2008) and earlier. It is defined as: . This error rate cannot be strictly controlled because it is 1 when .

- was used by Benjamini and Hochberg, and later called "pFDR" by Storey (2002). It is defined as: . This error rate cannot be strictly controlled because it is 1 when . JD Storey promoted the use of the pFDR (a close relative of the FDR), and the q-value, which can be viewed as the proportion of false discoveries that we expect in an ordered table of results, up to the current line. Storey also promoted the idea (also mentioned by BH) that the actual number of null hypotheses, , can be estimated from the shape of the probability distribution curve. For example, in a set of data where all null hypotheses are true, 50% of results will yield probabilities between 0.5 and 1.0 (and the other 50% will yield probabilities between 0.0 and 0.5). We can therefore estimate by finding the number of results with and doubling it, and this permits refinement of our calculation of the pFDR at any particular cut-off in the data-set.

- False exceedance rate (the tail probability of FDP), defined as:

- (Weighted FDR). Associated with each hypothesis i is a weight , the weights capture importance/price. The W-FDR is defined as: .

- FDCR (False Discovery Cost Rate). Stemming from statistical process control: associated with each hypothesis i is a cost and with the intersection hypothesis a cost . The motivation is that stopping a production process may incur a fixed cost. It is defined as:

- PFER (per-family error rate) is defined as: .

- FNR (False non-discovery rates) by Sarkar; Genovese and Wasserman is defined as:

- is defined as:

- The local fdr is defined as:

False coverage rate

The false coverage rate (FCR) is, in a sense, the FDR analog to the confidence interval. FCR indicates the average rate of false coverage, namely, not covering the true parameters, among the selected intervals. The FCR gives a simultaneous coverage at a level for all of the parameters considered in the problem. Intervals with simultaneous coverage probability 1−q can control the FCR to be bounded by q. There are many FCR procedures such as: Bonferroni-Selected–Bonferroni-Adjusted, Adjusted BH-Selected CIs (Benjamini and Yekutieli (2005)), Bayes FCR (Yekutieli (2008)), and other Bayes methods.

![{\displaystyle \left(E[V]/R\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0317c44300877d98b741d2e55adc2906dc0e43f5)

![{\displaystyle \mathrm {FDR} =Q_{e}=\mathrm {E} \!\left[Q\right]=1-{\text{precision}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/db56153c837a4bd6e467ca2ccd1569b693f07ad4)

![{\displaystyle \mathrm {E} \!\left[Q\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f84c0e62ed708690281318ea5a277a5e84ced29)

![{\displaystyle \mathrm {FDR} =\mathrm {E} \!\left[V/R|R>0\right]\cdot \mathrm {P} \!\left(R>0\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9004d0644e5afccb936bd1a4c86f3f03c26b3043)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {MFDR} }{c(m)}}=\alpha (m+1)/(2m[\ln(m)+\gamma ]+1)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a9c2e5cd844b5970b572279b3d8a6918e2c2ea59)

![\mathrm{PCER} = E \left[ \frac{V}{m} \right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c29dfa27a286355267f83672be2fc48110320d7b)

![Q' = \frac{E[V]}{R}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f30d998838c4bd9f144d3cdfd88b0e7410c730b)

![\mathrm{FDR}_{-1} = Fdr = \frac{E[V]}{E[R]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/53d466556dcaf918823cf48aa1b3f2917de7df70)

![\mathrm{FDR}_{+1} = pFDR = E \left[ \left. {\frac{V}{R}} \right| R>0 \right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5c49e753d7dc0d06bdc0dcd08de990d9fbbea750)