Memory is often understood as an informational processing system with explicit and implicit functioning that is made up of a sensory processor, short-term (or working) memory, and long-term memory. This can be related to the neuron. The sensory processor allows information from the outside world to be sensed in the form of chemical and physical stimuli and attended to various levels of focus and intent. Working memory serves as an encoding and retrieval processor. Information in the form of stimuli is encoded in accordance with explicit or implicit functions by the working memory processor. The working memory also retrieves information from previously stored material. Finally, the function of long-term memory is to store through various categorical models or systems.

Declarative, or explicit, memory is the conscious storage and recollection of data. Under declarative memory resides semantic and episodic memory. Semantic memory refers to memory that is encoded with specific meaning. Meanwhile, episodic memory refers to information that is encoded along a spatial and temporal plane. Declarative memory is usually the primary process thought of when referencing memory. Non-declarative, or implicit, memory is the unconscious storage and recollection of information. An example of a non-declarative process would be the unconscious learning or retrieval of information by way of procedural memory, or a priming phenomenon. Priming is the process of subliminally arousing specific responses from memory and shows that not all memory is consciously activated, whereas procedural memory is the slow and gradual learning of skills that often occurs without conscious attention to learning.

Memory is not a perfect processor, and is affected by many factors. The ways by which information is encoded, stored, and retrieved can all be corrupted. Pain, for example, has been identified as a physical condition that impairs memory, and has been noted in animal models as well as chronic pain patients. The amount of attention given new stimuli can diminish the amount of information that becomes encoded for storage. Also, the storage process can become corrupted by physical damage to areas of the brain that are associated with memory storage, such as the hippocampus. Finally, the retrieval of information from long-term memory can be disrupted because of decay within long-term memory. Normal functioning, decay over time, and brain damage all affect the accuracy and capacity of the memory.

Sensory memory

Sensory memory holds information, derived from the senses, less than one second after an item is perceived. The ability to look at an item and remember what it looked like with just a split second of observation, or memorization, is an example of sensory memory. It is out of cognitive control and is an automatic response. With very short presentations, participants often report that they seem to "see" more than they can actually report. The first precise experiments exploring this form of sensory memory were conducted by George Sperling (1963) using the "partial report paradigm." Subjects were presented with a grid of 12 letters, arranged into three rows of four. After a brief presentation, subjects were then played either a high, medium or low tone, cuing them which of the rows to report. Based on these partial report experiments, Sperling was able to show that the capacity of sensory memory was approximately 12 items, but that it degraded very quickly (within a few hundred milliseconds). Because this form of memory degrades so quickly, participants would see the display but be unable to report all of the items (12 in the "whole report" procedure) before they decayed. This type of memory cannot be prolonged via rehearsal.

Three types of sensory memories exist. Iconic memory is a fast decaying store of visual information, a type of sensory memory that briefly stores an image that has been perceived for a small duration. Echoic memory is a fast decaying store of auditory information, also a sensory memory that briefly stores sounds that have been perceived for short durations. Haptic memory is a type of sensory memory that represents a database for touch stimuli.

Short-term memory

Short-term memory, not to be confused with working memory, allows recall for a period of several seconds to a minute without rehearsal. Its capacity, however, is very limited. In 1956, George A. Miller (1920–2012), when working at Bell Laboratories, conducted experiments showing that the store of short-term memory was 7±2 items. (Hence, the title of his famous paper, "The Magical Number 7±2.") Modern perspectives estimate the capacity of short-term memory to be lower, typically on the order of 4–5 items, or argue for a more flexible limit based on information instead of items. Memory capacity can be increased through a process called chunking. For example, in recalling a ten-digit telephone number, a person could chunk the digits into three groups: first, the area code (such as 123), then a three-digit chunk (456), and, last, a four-digit chunk (7890). This method of remembering telephone numbers is far more effective than attempting to remember a string of 10 digits; this is because we are able to chunk the information into meaningful groups of numbers. This is reflected in some countries' tendencies to display telephone numbers as several chunks of two to four numbers.

Short-term memory is believed to rely mostly on an acoustic code for storing information, and to a lesser extent on a visual code. Conrad (1964) found that test subjects had more difficulty recalling collections of letters that were acoustically similar, e.g., E, P, D. Confusion with recalling acoustically similar letters rather than visually similar letters implies that the letters were encoded acoustically. Conrad's (1964) study, however, deals with the encoding of written text. Thus, while the memory of written language may rely on acoustic components, generalizations to all forms of memory cannot be made.

Long-term memory

The storage in sensory memory and short-term memory generally has a strictly limited capacity and duration. This means that information is not retained indefinitely. By contrast, while the total capacity of long-term memory has yet to be established, it can store much larger quantities of information. Furthermore, it can store this information for a much longer duration, potentially for a whole life span. For example, given a random seven-digit number, one may remember it for only a few seconds before forgetting, suggesting it was stored in short-term memory. On the other hand, one can remember telephone numbers for many years through repetition; this information is said to be stored in long-term memory.

While short-term memory encodes information acoustically, long-term memory encodes it semantically: Baddeley (1966) discovered that, after 20 minutes, test subjects had the most difficulty recalling a collection of words that had similar meanings (e.g. big, large, great, huge) long-term. Another part of long-term memory is episodic memory, "which attempts to capture information such as 'what', 'when' and 'where'". With episodic memory, individuals are able to recall specific events such as birthday parties and weddings.

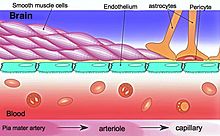

Short-term memory is supported by transient patterns of neuronal communication, dependent on regions of the frontal lobe (especially dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and the parietal lobe. Long-term memory, on the other hand, is maintained by more stable and permanent changes in neural connections widely spread throughout the brain. The hippocampus is essential (for learning new information) to the consolidation of information from short-term to long-term memory, although it does not seem to store information itself. It was thought that without the hippocampus new memories were unable to be stored into long-term memory and that there would be a very short attention span, as first gleaned from patient Henry Molaison after what was thought to be the full removal of both his hippocampi. More recent examination of his brain, post-mortem, shows that the hippocampus was more intact than first thought, throwing theories drawn from the initial data into question. The hippocampus may be involved in changing neural connections for a period of three months or more after the initial learning.

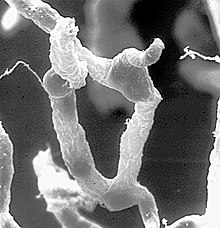

Research has suggested that long-term memory storage in humans may be maintained by DNA methylation, and the 'prion' gene.

Further research investigated the molecular basis for long-term memory. By 2015 it had become clear that long-term memory requires gene transcription activation and de novo protein synthesis. Long-term memory formation depends on both the activation of memory promoting genes and the inhibition of memory suppressor genes, and DNA methylation/DNA demethylation was found to be a major mechanism for achieving this dual regulation.

Rats with a new, strong long-term memory due to contextual fear conditioning have reduced expression of about 1,000 genes and increased expression of about 500 genes in the hippocampus 24 hours after training, thus exhibiting modified expression of 9.17% of the rat hippocampal genome. Reduced gene expressions were associated with methylations of those genes.

Considerable further research into long-term memory has illuminated the molecular mechanisms by which methylations are established or removed, as reviewed in 2022. These mechanisms include, for instance, signal-responsive TOP2B-induced double-strand breaks in immediate early genes. Also the messenger RNAs of many genes that had been subjected to methylation-controlled increases or decreases are transported by neural granules (messenger RNP) to the dendritic spines. At these locations the messenger RNAs can be translated into the proteins that control signaling at neuronal synapses.

Multi-store model

The multi-store model (also known as Atkinson–Shiffrin memory model) was first described in 1968 by Atkinson and Shiffrin.

The multi-store model has been criticised for being too simplistic. For instance, long-term memory is believed to be actually made up of multiple subcomponents, such as episodic and procedural memory. It also proposes that rehearsal is the only mechanism by which information eventually reaches long-term storage, but evidence shows us capable of remembering things without rehearsal.

The model also shows all the memory stores as being a single unit whereas research into this shows differently. For example, short-term memory can be broken up into different units such as visual information and acoustic information. In a study by Zlonoga and Gerber (1986), patient 'KF' demonstrated certain deviations from the Atkinson–Shiffrin model. Patient KF was brain damaged, displaying difficulties regarding short-term memory. Recognition of sounds such as spoken numbers, letters, words, and easily identifiable noises (such as doorbells and cats meowing) were all impacted. Visual short-term memory was unaffected, suggesting a dichotomy between visual and audial memory.

Working memory

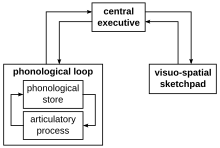

In 1974 Baddeley and Hitch proposed a "working memory model" that replaced the general concept of short-term memory with active maintenance of information in short-term storage. In this model, working memory consists of three basic stores: the central executive, the phonological loop, and the visuo-spatial sketchpad. In 2000 this model was expanded with the multimodal episodic buffer (Baddeley's model of working memory).

The central executive essentially acts as an attention sensory store. It channels information to the three component processes: the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketchpad, and the episodic buffer.

The phonological loop stores auditory information by silently rehearsing sounds or words in a continuous loop: the articulatory process (for example the repetition of a telephone number over and over again). A short list of data is easier to remember. The phonological loop is occasionally disrupted. Irrelevant speech or background noise can impede the phonological loop. Articulatory suppression can also confuse encoding and words that sound similar can be switched or misremembered through the phonological similarity effect. the phonological loop also has a limit to how much it can hold at once which means that it is easier to remember a lot of short words rather than a lot of long words, according to the word length effect.

The visuospatial sketchpad stores visual and spatial information. It is engaged when performing spatial tasks (such as judging distances) or visual ones (such as counting the windows on a house or imagining images). Those with aphantasia will not be able to engage the visuospatial sketchpad.

The episodic buffer is dedicated to linking information across domains to form integrated units of visual, spatial, and verbal information and chronological ordering (e.g., the memory of a story or a movie scene). The episodic buffer is also assumed to have links to long-term memory and semantic meaning.

The working memory model explains many practical observations, such as why it is easier to do two different tasks, one verbal and one visual, than two similar tasks, and the aforementioned word-length effect. Working memory is also the premise for what allows us to do everyday activities involving thought. It is the section of memory where we carry out thought processes and use them to learn and reason about topics.

Types

Researchers distinguish between recognition and recall memory. Recognition memory tasks require individuals to indicate whether they have encountered a stimulus (such as a picture or a word) before. Recall memory tasks require participants to retrieve previously learned information. For example, individuals might be asked to produce a series of actions they have seen before or to say a list of words they have heard before.

By information type

Topographical memory involves the ability to orient oneself in space, to recognize and follow an itinerary, or to recognize familiar places. Getting lost when traveling alone is an example of the failure of topographic memory.

Flashbulb memories are clear episodic memories of unique and highly emotional events. People remembering where they were or what they were doing when they first heard the news of President Kennedy's assassination, the Sydney Siege or of 9/11 are examples of flashbulb memories.

Long-term

Anderson (1976) divides long-term memory into declarative (explicit) and procedural (implicit) memories.

Declarative

Declarative memory requires conscious recall, in that some conscious process must call back the information. It is sometimes called explicit memory, since it consists of information that is explicitly stored and retrieved. Declarative memory can be further sub-divided into semantic memory, concerning principles and facts taken independent of context; and episodic memory, concerning information specific to a particular context, such as a time and place. Semantic memory allows the encoding of abstract knowledge about the world, such as "Paris is the capital of France". Episodic memory, on the other hand, is used for more personal memories, such as the sensations, emotions, and personal associations of a particular place or time. Episodic memories often reflect the "firsts" in life such as a first kiss, first day of school or first time winning a championship. These are key events in one's life that can be remembered clearly.

Research suggests that declarative memory is supported by several functions of the medial temporal lobe system which includes the hippocampus. Autobiographical memory – memory for particular events within one's own life – is generally viewed as either equivalent to, or a subset of, episodic memory. Visual memory is part of memory preserving some characteristics of our senses pertaining to visual experience. One is able to place in memory information that resembles objects, places, animals or people in sort of a mental image. Visual memory can result in priming and it is assumed some kind of perceptual representational system underlies this phenomenon.

Procedural

In contrast, procedural memory (or implicit memory) is not based on the conscious recall of information, but on implicit learning. It can best be summarized as remembering how to do something. Procedural memory is primarily used in learning motor skills and can be considered a subset of implicit memory. It is revealed when one does better in a given task due only to repetition – no new explicit memories have been formed, but one is unconsciously accessing aspects of those previous experiences. Procedural memory involved in motor learning depends on the cerebellum and basal ganglia.

A characteristic of procedural memory is that the things remembered are automatically translated into actions, and thus sometimes difficult to describe. Some examples of procedural memory include the ability to ride a bike or tie shoelaces.

By temporal direction

Another major way to distinguish different memory functions is whether the content to be remembered is in the past, retrospective memory, or in the future, prospective memory. John Meacham introduced this distinction in a paper presented at the 1975 American Psychological Association annual meeting and subsequently included by Ulric Neisser in his 1982 edited volume, Memory Observed: Remembering in Natural Contexts. Thus, retrospective memory as a category includes semantic, episodic and autobiographical memory. In contrast, prospective memory is memory for future intentions, or remembering to remember (Winograd, 1988). Prospective memory can be further broken down into event- and time-based prospective remembering. Time-based prospective memories are triggered by a time-cue, such as going to the doctor (action) at 4pm (cue). Event-based prospective memories are intentions triggered by cues, such as remembering to post a letter (action) after seeing a mailbox (cue). Cues do not need to be related to the action (as the mailbox/letter example), and lists, sticky-notes, knotted handkerchiefs, or string around the finger all exemplify cues that people use as strategies to enhance prospective memory.

Study techniques

To assess infants

Infants do not have the language ability to report on their memories and so verbal reports cannot be used to assess very young children's memory. Throughout the years, however, researchers have adapted and developed a number of measures for assessing both infants' recognition memory and their recall memory. Habituation and operant conditioning techniques have been used to assess infants' recognition memory and the deferred and elicited imitation techniques have been used to assess infants' recall memory.

Techniques used to assess infants' recognition memory include the following:

- Visual paired comparison procedure (relies on habituation): infants are first presented with pairs of visual stimuli, such as two black-and-white photos of human faces, for a fixed amount of time; then, after being familiarized with the two photos, they are presented with the "familiar" photo and a new photo. The time spent looking at each photo is recorded. Looking longer at the new photo indicates that they remember the "familiar" one. Studies using this procedure have found that 5- to 6-month-olds can retain information for as long as fourteen days.

- Operant conditioning technique: infants are placed in a crib and a ribbon that is connected to a mobile overhead is tied to one of their feet. Infants notice that when they kick their foot the mobile moves – the rate of kicking increases dramatically within minutes. Studies using this technique have revealed that infants' memory substantially improves over the first 18-months. Whereas 2- to 3-month-olds can retain an operant response (such as activating the mobile by kicking their foot) for a week, 6-month-olds can retain it for two weeks, and 18-month-olds can retain a similar operant response for as long as 13 weeks.

Techniques used to assess infants' recall memory include the following:

- Deferred imitation technique: an experimenter shows infants a unique sequence of actions (such as using a stick to push a button on a box) and then, after a delay, asks the infants to imitate the actions. Studies using deferred imitation have shown that 14-month-olds' memories for the sequence of actions can last for as long as four months.

- Elicited imitation technique: is very similar to the deferred imitation technique; the difference is that infants are allowed to imitate the actions before the delay. Studies using the elicited imitation technique have shown that 20-month-olds can recall the action sequences twelve months later.

To assess children and older adults

Researchers use a variety of tasks to assess older children and adults' memory. Some examples are:

- Paired associate learning – when one learns to associate one specific word with another. For example, when given a word such as "safe" one must learn to say another specific word, such as "green". This is stimulus and response.

- Free recall – during this task a subject would be asked to study a list of words and then later they will be asked to recall or write down as many words that they can remember, similar to free response questions. Earlier items are affected by retroactive interference (RI), which means the longer the list, the greater the interference, and the less likelihood that they are recalled. On the other hand, items that have been presented lastly suffer little RI, but suffer a great deal from proactive interference (PI), which means the longer the delay in recall, the more likely that the items will be lost.

- Cued recall – one is given a significant hints to help retrieve information that has been previously encoded into the person's memory; typically this can involve a word relating to the information being asked to remember. This is similar to fill in the blank assessments used in classrooms.

- Recognition – subjects are asked to remember a list of words or pictures, after which point they are asked to identify the previously presented words or pictures from among a list of alternatives that were not presented in the original list. This is similar to multiple choice assessments.

- Detection paradigm – individuals are shown a number of objects and color samples during a certain period of time. They are then tested on their visual ability to remember as much as they can by looking at testers and pointing out whether the testers are similar to the sample, or if any change is present.

- Savings method – compares the speed of originally learning to the speed of relearning it. The amount of time saved measures memory.

- Implicit-memory tasks – information is drawn from memory without conscious realization.

Failures

- Transience – memories degrade with the passing of time. This occurs in the storage stage of memory, after the information has been stored and before it is retrieved. This can happen in sensory, short-term, and long-term storage. It follows a general pattern where the information is rapidly forgotten during the first couple of days or years, followed by small losses in later days or years.

- Absent-mindedness – Memory failure due to the lack of attention. Attention plays a key role in storing information into long-term memory; without proper attention, the information might not be stored, making it impossible to be retrieved later.

Physiology

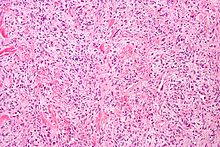

Brain areas involved in the neuroanatomy of memory such as the hippocampus, the amygdala, the striatum, or the mammillary bodies are thought to be involved in specific types of memory. For example, the hippocampus is believed to be involved in spatial learning and declarative learning, while the amygdala is thought to be involved in emotional memory.

Damage to certain areas in patients and animal models and subsequent memory deficits is a primary source of information. However, rather than implicating a specific area, it could be that damage to adjacent areas, or to a pathway traveling through the area is actually responsible for the observed deficit. Further, it is not sufficient to describe memory, and its counterpart, learning, as solely dependent on specific brain regions. Learning and memory are usually attributed to changes in neuronal synapses, thought to be mediated by long-term potentiation and long-term depression.

In general, the more emotionally charged an event or experience is, the better it is remembered; this phenomenon is known as the memory enhancement effect. Patients with amygdala damage, however, do not show a memory enhancement effect.

Hebb distinguished between short-term and long-term memory. He postulated that any memory that stayed in short-term storage for a long enough time would be consolidated into a long-term memory. Later research showed this to be false. Research has shown that direct injections of cortisol or epinephrine help the storage of recent experiences. This is also true for stimulation of the amygdala. This proves that excitement enhances memory by the stimulation of hormones that affect the amygdala. Excessive or prolonged stress (with prolonged cortisol) may hurt memory storage. Patients with amygdalar damage are no more likely to remember emotionally charged words than nonemotionally charged ones. The hippocampus is important for explicit memory. The hippocampus is also important for memory consolidation. The hippocampus receives input from different parts of the cortex and sends its output out to different parts of the brain also. The input comes from secondary and tertiary sensory areas that have processed the information a lot already. Hippocampal damage may also cause memory loss and problems with memory storage. This memory loss includes retrograde amnesia which is the loss of memory for events that occurred shortly before the time of brain damage.

Cognitive neuroscience

Cognitive neuroscientists consider memory as the retention, reactivation, and reconstruction of the experience-independent internal representation. The term of internal representation implies that such a definition of memory contains two components: the expression of memory at the behavioral or conscious level, and the underpinning physical neural changes (Dudai 2007). The latter component is also called engram or memory traces (Semon 1904). Some neuroscientists and psychologists mistakenly equate the concept of engram and memory, broadly conceiving all persisting after-effects of experiences as memory; others argue against this notion that memory does not exist until it is revealed in behavior or thought (Moscovitch 2007).

One question that is crucial in cognitive neuroscience is how information and mental experiences are coded and represented in the brain. Scientists have gained much knowledge about the neuronal codes from the studies of plasticity, but most of such research has been focused on simple learning in simple neuronal circuits; it is considerably less clear about the neuronal changes involved in more complex examples of memory, particularly declarative memory that requires the storage of facts and events (Byrne 2007). Convergence-divergence zones might be the neural networks where memories are stored and retrieved. Considering that there are several kinds of memory, depending on types of represented knowledge, underlying mechanisms, processes functions and modes of acquisition, it is likely that different brain areas support different memory systems and that they are in mutual relationships in neuronal networks: "components of memory representation are distributed widely across different parts of the brain as mediated by multiple neocortical circuits".

- Encoding. Encoding of working memory involves the spiking of individual neurons induced by sensory input, which persists even after the sensory input disappears (Jensen and Lisman 2005; Fransen et al. 2002). Encoding of episodic memory involves persistent changes in molecular structures that alter synaptic transmission between neurons. Examples of such structural changes include long-term potentiation (LTP) or spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). The persistent spiking in working memory can enhance the synaptic and cellular changes in the encoding of episodic memory (Jensen and Lisman 2005).

- Working memory. Recent functional imaging studies detected working memory signals in both medial temporal lobe (MTL), a brain area strongly associated with long-term memory, and prefrontal cortex (Ranganath et al. 2005), suggesting a strong relationship between working memory and long-term memory. However, the substantially more working memory signals seen in the prefrontal lobe suggest that this area plays a more important role in working memory than MTL (Suzuki 2007).

- Consolidation and reconsolidation. Short-term memory (STM) is temporary and subject to disruption, while long-term memory (LTM), once consolidated, is persistent and stable. Consolidation of STM into LTM at the molecular level presumably involves two processes: synaptic consolidation and system consolidation. The former involves a protein synthesis process in the medial temporal lobe (MTL), whereas the latter transforms the MTL-dependent memory into an MTL-independent memory over months to years (Ledoux 2007). In recent years, such traditional consolidation dogma has been re-evaluated as a result of the studies on reconsolidation. These studies showed that prevention after retrieval affects subsequent retrieval of the memory (Sara 2000). New studies have shown that post-retrieval treatment with protein synthesis inhibitors and many other compounds can lead to an amnestic state (Nadel et al. 2000b; Alberini 2005; Dudai 2006). These findings on reconsolidation fit with the behavioral evidence that retrieved memory is not a carbon copy of the initial experiences, and memories are updated during retrieval.

Genetics

Study of the genetics of human memory is in its infancy though many genes have been investigated for their association to memory in humans and non-human animals. A notable initial success was the association of APOE with memory dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. The search for genes associated with normally varying memory continues. One of the first candidates for normal variation in memory is the protein KIBRA, which appears to be associated with the rate at which material is forgotten over a delay period. There has been some evidence that memories are stored in the nucleus of neurons.

Genetic underpinnings

Several genes, proteins and enzymes have been extensively researched for their association with memory. Long-term memory, unlike short-term memory, is dependent upon the synthesis of new proteins. This occurs within the cellular body, and concerns the particular transmitters, receptors, and new synapse pathways that reinforce the communicative strength between neurons. The production of new proteins devoted to synapse reinforcement is triggered after the release of certain signaling substances (such as calcium within hippocampal neurons) in the cell. In the case of hippocampal cells, this release is dependent upon the expulsion of magnesium (a binding molecule) that is expelled after significant and repetitive synaptic signaling. The temporary expulsion of magnesium frees NMDA receptors to release calcium in the cell, a signal that leads to gene transcription and the construction of reinforcing proteins. For more information, see long-term potentiation (LTP).

One of the newly synthesized proteins in LTP is also critical for maintaining long-term memory. This protein is an autonomously active form of the enzyme protein kinase C (PKC), known as PKMζ. PKMζ maintains the activity-dependent enhancement of synaptic strength and inhibiting PKMζ erases established long-term memories, without affecting short-term memory or, once the inhibitor is eliminated, the ability to encode and store new long-term memories is restored. Also, BDNF is important for the persistence of long-term memories.

The long-term stabilization of synaptic changes is also determined by a parallel increase of pre- and postsynaptic structures such as axonal bouton, dendritic spine and postsynaptic density. On the molecular level, an increase of the postsynaptic scaffolding proteins PSD-95 and HOMER1c has been shown to correlate with the stabilization of synaptic enlargement. The cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is a transcription factor which is believed to be important in consolidating short-term to long-term memories, and which is believed to be downregulated in Alzheimer's disease.

DNA methylation and demethylation

Rats exposed to an intense learning event may retain a life-long memory of the event, even after a single training session. The long-term memory of such an event appears to be initially stored in the hippocampus, but this storage is transient. Much of the long-term storage of the memory seems to take place in the anterior cingulate cortex. When such an exposure was experimentally applied, more than 5,000 differently methylated DNA regions appeared in the hippocampus neuronal genome of the rats at one and at 24 hours after training.e alterations in methylation pattern occurred at many genes that were downregulated, often due to the formation of new 5-methylcytosine sites in CpG rich regions of the genome. Furthermore, many other genes were upregulated, likely often due to hypomethylation. Hypomethylation often results from the removal of methyl groups from previously existing 5-methylcytosines in DNA. Demethylation is carried out by several proteins acting in concert, including the TET enzymes as well as enzymes of the DNA base excision repair pathway (see Epigenetics in learning and memory). The pattern of induced and repressed genes in brain neurons subsequent to an intense learning event likely provides the molecular basis for a long-term memory of the event.

Epigenetics

Studies of the molecular basis for memory formation indicate that epigenetic mechanisms operating in neurons in the brain play a central role in determining this capability. Key epigenetic mechanisms involved in memory include the methylation and demethylation of neuronal DNA, as well as modifications of histone proteins including methylations, acetylations and deacetylations.

Stimulation of brain activity in memory formation is often accompanied by the generation of damage in neuronal DNA that is followed by repair associated with persistent epigenetic alterations. In particular the DNA repair processes of non-homologous end joining and base excision repair are employed in memory formation.

DNA topoisomerase 2-beta in learning and memory

During a new learning experience, a set of genes is rapidly expressed in the brain. This induced gene expression is considered to be essential for processing the information being learned. Such genes are referred to as immediate early genes (IEGs). DNA topoisomerase 2-beta (TOP2B) activity is essential for the expression of IEGs in a type of learning experience in mice termed associative fear memory. Such a learning experience appears to rapidly trigger TOP2B to induce double-strand breaks in the promoter DNA of IEG genes that function in neuroplasticity. Repair of these induced breaks is associated with DNA demethylation of IEG gene promoters allowing immediate expression of these IEG genes.

The double-strand breaks that are induced during a learning experience are not immediately repaired. About 600 regulatory sequences in promoters and about 800 regulatory sequences in enhancers appear to depend on double strand breaks initiated by topoisomerase 2-beta (TOP2B) for activation. The induction of particular double-strand breaks are specific with respect to their inducing signal. When neurons are activated in vitro, just 22 of TOP2B-induced double-strand breaks occur in their genomes.

Such TOP2B-induced double-strand breaks are accompanied by at least four enzymes of the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway (DNA-PKcs, KU70, KU80, and DNA LIGASE IV) (see Figure). These enzymes repair the double-strand breaks within about 15 minutes to two hours. The double-strand breaks in the promoter are thus associated with TOP2B and at least these four repair enzymes. These proteins are present simultaneously on a single promoter nucleosome (there are about 147 nucleotides in the DNA sequence wrapped around a single nucleosome) located near the transcription start site of their target gene.

The double-strand break introduced by TOP2B apparently frees the part of the promoter at an RNA polymerase-bound transcription start site to physically move to its associated enhancer (see regulatory sequence). This allows the enhancer, with its bound transcription factors and mediator proteins, to directly interact with the RNA polymerase paused at the transcription start site to start transcription.

Contextual fear conditioning in the mouse causes the mouse to have a long-term memory and fear of the location in which it occurred. Contextual fear conditioning causes hundreds of DSBs in mouse brain medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and hippocampus neurons (see Figure: Brain regions involved in memory formation). These DSBs predominately activate genes involved in synaptic processes, that are important for learning and memory.

Chemistry of Memory : Molecular basis of thought storage and memory formation

A considerable amount of research is underway on the molecular basis of thought storage, memory consolidation and formation of logical thought processes.In 2001 it has been proposed that the folding of glycoproteins by intermolecular or intramolecular hydrogen bonding may be the key process involved in memory storage. The hydrogen bonding protein patterns hypothesis (HBPPH) proposes the formation of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups of sugar moieties present in the glycoproteins with hydroxyl (or NH) groups of other sugar moieties or biomolecules that can lead to the creation of certain partly folded protein patterns. This provides a reasonable mechanism by which the brain may be able to gather and store information by the construction of intermolecular and intramolecular networks of folded glycoproteins. Support for partly folded proteins being involved in memory processes has come from recent researches in the field.

In infancy

Up until the mid-1980s it was assumed that infants could not encode, retain, and retrieve information. A growing body of research now indicates that infants as young as 6-months can recall information after a 24-hour delay. Furthermore, research has revealed that as infants grow older they can store information for longer periods of time; 6-month-olds can recall information after a 24-hour period, 9-month-olds after up to five weeks, and 20-month-olds after as long as twelve months. In addition, studies have shown that with age, infants can store information faster. Whereas 14-month-olds can recall a three-step sequence after being exposed to it once, 6-month-olds need approximately six exposures in order to be able to remember it.

Although 6-month-olds can recall information over the short-term, they have difficulty recalling the temporal order of information. It is only by 9 months of age that infants can recall the actions of a two-step sequence in the correct temporal order – that is, recalling step 1 and then step 2. In other words, when asked to imitate a two-step action sequence (such as putting a toy car in the base and pushing in the plunger to make the toy roll to the other end), 9-month-olds tend to imitate the actions of the sequence in the correct order (step 1 and then step 2). Younger infants (6-month-olds) can only recall one step of a two-step sequence. Researchers have suggested that these age differences are probably due to the fact that the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and the frontal components of the neural network are not fully developed at the age of 6-months.

In fact, the term 'infantile amnesia' refers to the phenomenon of accelerated forgetting during infancy. Importantly, infantile amnesia is not unique to humans, and preclinical research (using rodent models) provides insight into the precise neurobiology of this phenomenon. A review of the literature from behavioral neuroscientist Jee Hyun Kim suggests that accelerated forgetting during early life is at least partly due to rapid growth of the brain during this period.

Aging

One of the key concerns of older adults is the experience of memory loss, especially as it is one of the hallmark symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. However, memory loss is qualitatively different in normal aging from the kind of memory loss associated with a diagnosis of Alzheimer's (Budson & Price, 2005). Research has revealed that individuals' performance on memory tasks that rely on frontal regions declines with age. Older adults tend to exhibit deficits on tasks that involve knowing the temporal order in which they learned information; source memory tasks that require them to remember the specific circumstances or context in which they learned information; and prospective memory tasks that involve remembering to perform an act at a future time. Older adults can manage their problems with prospective memory by using appointment books, for example.

Gene transcription profiles were determined for the human frontal cortex of individuals from age 26 to 106 years. Numerous genes were identified with reduced expression after age 40, and especially after age 70. Genes that play central roles in memory and learning were among those showing the most significant reduction with age. There was also a marked increase in DNA damage, likely oxidative damage, in the promoters of those genes with reduced expression. It was suggested that DNA damage may reduce the expression of selectively vulnerable genes involved in memory and learning.

Disorders

Much of the current knowledge of memory has come from studying memory disorders, particularly loss of memory, known as amnesia. Amnesia can result from extensive damage to: (a) the regions of the medial temporal lobe, such as the hippocampus, dentate gyrus, subiculum, amygdala, the parahippocampal, entorhinal, and perirhinal cortices or the (b) midline diencephalic region, specifically the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus and the mammillary bodies of the hypothalamus. There are many sorts of amnesia, and by studying their different forms, it has become possible to observe apparent defects in individual sub-systems of the brain's memory systems, and thus hypothesize their function in the normally working brain. Other neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease can also affect memory and cognition. Hyperthymesia, or hyperthymesic syndrome, is a disorder that affects an individual's autobiographical memory, essentially meaning that they cannot forget small details that otherwise would not be stored. Korsakoff's syndrome, also known as Korsakoff's psychosis, amnesic-confabulatory syndrome, is an organic brain disease that adversely affects memory by widespread loss or shrinkage of neurons within the prefrontal cortex.

While not a disorder, a common temporary failure of word retrieval from memory is the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. Those with anomic aphasia (also called nominal aphasia or Anomia), however, do experience the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon on an ongoing basis due to damage to the frontal and parietal lobes of the brain.

Memory dysfunction can also occur after viral infections. Many patients recovering from COVID-19 experience memory lapses. Other viruses can also elicit memory dysfunction, including SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, Ebola virus and even influenza virus.

Influencing factors

Interference can hamper memorization and retrieval. There is retroactive interference, when learning new information makes it harder to recall old information and proactive interference, where prior learning disrupts recall of new information. Although interference can lead to forgetting, it is important to keep in mind that there are situations when old information can facilitate learning of new information. Knowing Latin, for instance, can help an individual learn a related language such as French – this phenomenon is known as positive transfer.

Stress

Stress has a significant effect on memory formation and learning. In response to stressful situations, the brain releases hormones and neurotransmitters (ex. glucocorticoids and catecholamines) which affect memory encoding processes in the hippocampus. Behavioural research on animals shows that chronic stress produces adrenal hormones which impact the hippocampal structure in the brains of rats. An experimental study by German cognitive psychologists L. Schwabe and O. Wolf demonstrates how learning under stress also decreases memory recall in humans. In this study, 48 healthy female and male university students participated in either a stress test or a control group. Those randomly assigned to the stress test group had a hand immersed in ice cold water (the reputable SECPT or 'Socially Evaluated Cold Pressor Test') for up to three minutes, while being monitored and videotaped. Both the stress and control groups were then presented with 32 words to memorize. Twenty-four hours later, both groups were tested to see how many words they could remember (free recall) as well as how many they could recognize from a larger list of words (recognition performance). The results showed a clear impairment of memory performance in the stress test group, who recalled 30% fewer words than the control group. The researchers suggest that stress experienced during learning distracts people by diverting their attention during the memory encoding process.

However, memory performance can be enhanced when material is linked to the learning context, even when learning occurs under stress. A separate study by cognitive psychologists Schwabe and Wolf shows that when retention testing is done in a context similar to or congruent with the original learning task (i.e., in the same room), memory impairment and the detrimental effects of stress on learning can be attenuated. Seventy-two healthy female and male university students, randomly assigned to the SECPT stress test or to a control group, were asked to remember the locations of 15 pairs of picture cards – a computerized version of the card game "Concentration" or "Memory". The room in which the experiment took place was infused with the scent of vanilla, as odour is a strong cue for memory. Retention testing took place the following day, either in the same room with the vanilla scent again present, or in a different room without the fragrance. The memory performance of subjects who experienced stress during the object-location task decreased significantly when they were tested in an unfamiliar room without the vanilla scent (an incongruent context); however, the memory performance of stressed subjects showed no impairment when they were tested in the original room with the vanilla scent (a congruent context). All participants in the experiment, both stressed and unstressed, performed faster when the learning and retrieval contexts were similar.

This research on the effects of stress on memory may have practical implications for education, for eyewitness testimony and for psychotherapy: students may perform better when tested in their regular classroom rather than an exam room, eyewitnesses may recall details better at the scene of an event than in a courtroom, and persons with post-traumatic stress may improve when helped to situate their memories of a traumatic event in an appropriate context.

Stressful life experiences may be a cause of memory loss as a person ages. Glucocorticoids that are released during stress cause damage to neurons that are located in the hippocampal region of the brain. Therefore, the more stressful situations that someone encounters, the more susceptible they are to memory loss later on. The CA1 neurons found in the hippocampus are destroyed due to glucocorticoids decreasing the release of glucose and the reuptake of glutamate. This high level of extracellular glutamate allows calcium to enter NMDA receptors which in return kills neurons. Stressful life experiences can also cause repression of memories where a person moves an unbearable memory to the unconscious mind. This directly relates to traumatic events in one's past such as kidnappings, being prisoners of war or sexual abuse as a child.

The more long term the exposure to stress is, the more impact it may have. However, short term exposure to stress also causes impairment in memory by interfering with the function of the hippocampus. Research shows that subjects placed in a stressful situation for a short amount of time still have blood glucocorticoid levels that have increased drastically when measured after the exposure is completed. When subjects are asked to complete a learning task after short term exposure they often have difficulties. Prenatal stress also hinders the ability to learn and memorize by disrupting the development of the hippocampus and can lead to unestablished long term potentiation in the offspring of severely stressed parents. Although the stress is applied prenatally, the offspring show increased levels of glucocorticoids when they are subjected to stress later on in life. One explanation for why children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to display poorer memory performance than their higher-income peers is the effects of stress accumulated over the course of the lifetime. The effects of low income on the developing hippocampus is also thought be mediated by chronic stress responses which may explain why children from lower and higher-income backgrounds differ in terms of memory performance.

Sleep

Making memories occurs through a three-step process, which can be enhanced by sleep. The three steps are as follows:

- Acquisition which is the process of storage and retrieval of new information in memory

- Consolidation

- Recall

Sleep affects memory consolidation. During sleep, the neural connections in the brain are strengthened. This enhances the brain's abilities to stabilize and retain memories. There have been several studies which show that sleep improves the retention of memory, as memories are enhanced through active consolidation. System consolidation takes place during slow-wave sleep (SWS). This process implicates that memories are reactivated during sleep, but that the process does not enhance every memory. It also implicates that qualitative changes are made to the memories when they are transferred to long-term store during sleep. During sleep, the hippocampus replays the events of the day for the neocortex. The neocortex then reviews and processes memories, which moves them into long-term memory. When one does not get enough sleep it makes it more difficult to learn as these neural connections are not as strong, resulting in a lower retention rate of memories. Sleep deprivation makes it harder to focus, resulting in inefficient learning. Furthermore, some studies have shown that sleep deprivation can lead to false memories as the memories are not properly transferred to long-term memory. One of the primary functions of sleep is thought to be the improvement of the consolidation of information, as several studies have demonstrated that memory depends on getting sufficient sleep between training and test. Additionally, data obtained from neuroimaging studies have shown activation patterns in the sleeping brain that mirror those recorded during the learning of tasks from the previous day, suggesting that new memories may be solidified through such rehearsal.[128]

Construction for general manipulation

Although people often think that memory operates like recording equipment, this is not the case. The molecular mechanisms underlying the induction and maintenance of memory are very dynamic and comprise distinct phases covering a time window from seconds to even a lifetime. In fact, research has revealed that our memories are constructed: "current hypotheses suggest that constructive processes allow individuals to simulate and imagine future episodes, happenings, and scenarios. Since the future is not an exact repetition of the past, simulation of future episodes requires a complex system that can draw on the past in a manner that flexibly extracts and recombines elements of previous experiences – a constructive rather than a reproductive system." People can construct their memories when they encode them and/or when they recall them. To illustrate, consider a classic study conducted by Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer (1974) in which people were instructed to watch a film of a traffic accident and then asked about what they saw. The researchers found that the people who were asked, "How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?" gave higher estimates than those who were asked, "How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?" Furthermore, when asked a week later whether they had seen broken glass in the film, those who had been asked the question with smashed were twice more likely to report that they had seen broken glass than those who had been asked the question with hit (there was no broken glass depicted in the film). Thus, the wording of the questions distorted viewers' memories of the event. Importantly, the wording of the question led people to construct different memories of the event – those who were asked the question with smashed recalled a more serious car accident than they had actually seen. The findings of this experiment were replicated around the world, and researchers consistently demonstrated that when people were provided with misleading information they tended to misremember, a phenomenon known as the misinformation effect.

Research has revealed that asking individuals to repeatedly imagine actions that they have never performed or events that they have never experienced could result in false memories. For instance, Goff and Roediger (1998) asked participants to imagine that they performed an act (e.g., break a toothpick) and then later asked them whether they had done such a thing. Findings revealed that those participants who repeatedly imagined performing such an act were more likely to think that they had actually performed that act during the first session of the experiment. Similarly, Garry and her colleagues (1996) asked college students to report how certain they were that they experienced a number of events as children (e.g., broke a window with their hand) and then two weeks later asked them to imagine four of those events. The researchers found that one-fourth of the students asked to imagine the four events reported that they had actually experienced such events as children. That is, when asked to imagine the events they were more confident that they experienced the events.

Research reported in 2013 revealed that it is possible to artificially stimulate prior memories and artificially implant false memories in mice. Using optogenetics, a team of RIKEN-MIT scientists caused the mice to incorrectly associate a benign environment with a prior unpleasant experience from different surroundings. Some scientists believe that the study may have implications in studying false memory formation in humans, and in treating PTSD and schizophrenia.

Memory reconsolidation is when previously consolidated memories are recalled or retrieved from long-term memory to your active consciousness. During this process, memories can be further strengthened and added to but there is also risk of manipulation involved. We like to think of our memories as something stable and constant when they are stored in long-term memory but this is not the case. There are a large number of studies that found that consolidation of memories is not a singular event but are put through the process again, known as reconsolidation. This is when a memory is recalled or retrieved and placed back into your working memory. The memory is now open to manipulation from outside sources and the misinformation effect which could be due to misattributing the source of the inconsistent information, with or without an intact original memory trace (Lindsay and Johnson, 1989). One thing that can be sure is that memory is malleable.

This new research into the concept of reconsolidation has opened the door to methods to help those with unpleasant memories or those that struggle with memories. An example of this is if you had a truly frightening experience and recall that memory in a less arousing environment, the memory will be weaken the next time it is retrieved. "Some studies suggest that over-trained or strongly reinforced memories do not undergo reconsolidation if reactivated the first few days after training, but do become sensitive to reconsolidation interference with time." This, however does not mean that all memory is susceptible to reconsolidation. There is evidence to suggest that memory that has undergone strong training and whether or not is it intentional is less likely to undergo reconsolidation. There was further testing done with rats and mazes that showed that reactivated memories were more susceptible to manipulation, in both good and bad ways, than newly formed memories. It is still not known whether or not these are new memories formed and it is an inability to retrieve the proper one for the situation or if it is a reconsolidated memory. Because the study of reconsolidation is still a newer concept, there is still debate on whether it should be considered scientifically sound.

Improving

A UCLA research study published in the June 2008 issue of the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry found that people can improve cognitive function and brain efficiency through simple lifestyle changes such as incorporating memory exercises, healthy eating, physical fitness and stress reduction into their daily lives. This study examined 17 subjects, (average age 53) with normal memory performance. Eight subjects were asked to follow a "brain healthy" diet, relaxation, physical, and mental exercise (brain teasers and verbal memory training techniques). After 14 days, they showed greater word fluency (not memory) compared to their baseline performance. No long-term follow-up was conducted; it is therefore unclear if this intervention has lasting effects on memory.

There are a loosely associated group of mnemonic principles and techniques that can be used to vastly improve memory known as the art of memory.

The International Longevity Center released in 2001 a report which includes in pages 14–16 recommendations for keeping the mind in good functionality until advanced age. Some of the recommendations are:

- to stay intellectually active through learning, training or reading

- to keep physically active so to promote blood circulation to the brain

- to socialize

- to reduce stress

- to keep sleep time regular

- to avoid depression or emotional instability

- to observe good nutrition.

Memorization is a method of learning that allows an individual to recall information verbatim. Rote learning is the method most often used. Methods of memorizing things have been the subject of much discussion over the years with some writers, such as Cosmos Rossellius using visual alphabets. The spacing effect shows that an individual is more likely to remember a list of items when rehearsal is spaced over an extended period of time. In contrast to this is cramming: an intensive memorization in a short period of time. The spacing effect is exploited to improve memory in spaced repetition flashcard training. Also relevant is the Zeigarnik effect, which states that people remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. The so-called Method of loci uses spatial memory to memorize non-spatial information.

In plants

Plants lack a specialized organ devoted to memory retention, so plant memory has been a controversial topic in recent years. New advances in the field have identified the presence of neurotransmitters in plants, adding to the hypothesis that plants are capable of remembering. Action potentials, a physiological response characteristic of neurons, have been shown to have an influence on plants as well, including in wound responses and photosynthesis. In addition to these homologous features of memory systems in both plants and animals, plants have also been observed to encode, store and retrieve basic short-term memories.

One of the most well-studied plants to show rudimentary memory is the Venus flytrap. Native to the subtropical wetlands of the eastern United States, Venus flytraps have evolved the ability to obtain meat for sustenance, likely due to the lack of nitrogen in the soil. This is done by two trap-forming leaf tips that snap shut once triggered by a potential prey. On each lobe, three trigger hairs await stimulation. In order to maximize the benefit-to-cost ratio, the plant enables a rudimentary form of memory in which two trigger hairs must be stimulated within thirty seconds in order to result in trap closure. This system ensures that the trap only closes when potential prey is within grasp.

The time lapse between trigger hair stimulations suggests that the plant can remember an initial stimulus long enough for a second stimulus to initiate trap closure. This memory is not encoded in a brain, as plants lack this specialized organ. Rather, information is stored in the form of cytoplasmic calcium levels. The first trigger causes a subthreshold cytoplasmic calcium influx. This initial trigger is not enough to activate trap closure, so a subsequent stimulus allows for a secondary influx of calcium. The latter calcium rise superimposes on the initial one, creating an action potential that passes threshold, resulting in trap closure. Researchers, to prove that an electrical threshold must be met to stimulate trap closure, excited a single trigger hair with a constant mechanical stimulus using Ag/AgCl electrodes. The trap closed after only a few seconds. This experiment demonstrated that the electrical threshold, not necessarily the number of trigger hair stimulations, was the contributing factor in Venus flytrap memory.

It has been shown that trap closure can be blocked using uncouplers and inhibitors of voltage-gated channels. After trap closure, these electrical signals stimulate glandular production of jasmonic acid and hydrolases, allowing for digestion of prey.

Many other plants exhibit the capacity to remember, including Mimosa pudica. An experimental apparatus was designed to drop potted mimosa plants repeatedly from the same distance and at the same speed. It was observed that the plants' defensive response of curling up their leaves decreased over the sixty times the experiment was repeated. To confirm that this was a mechanism of memory rather than exhaustion, some of the plants were shaken post experiment and displayed normal defensive responses of leaf curling. This experiment demonstrated long-term memory in the plants, as it was repeated a month later, and the plants were observed to remain unfazed by the dropping.