A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revolutionary" pertains to movements that would restore the state of affairs, or the principles, that prevailed during a prerevolutionary era.

Definition

A counter-revolution is opposition or resistance to a revolutionary movement. It can refer to attempts to defeat a revolutionary movement before it takes power, as well as attempts to restore the old regime after a successful revolution.

Europe

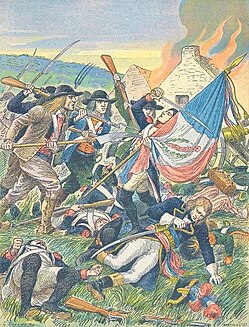

France

After the French Revolution, anti-clerical policies and the execution of King Louis XVI led to the War in the Vendée. This counter-revolution produced what is considered by some historians to be the first modern genocide. Monarchists and Catholics took up arms against the revolutionary French Republic in 1793 after the government asked that 300,000 men be conscripted into the Republican military in the levée en masse. The Vendeans also rose up against Napoleon's attempt to conscript them in 1815.

Germany

The German Empire, and its predecessors the Holy Roman Empire and German Confederation, operated under counterrevolutionary principles, with these monarchical federations crushing attempted uprisings in, for example, 1848. After the 1867–71 creation of a new German realm by Prussia, chancellor Otto von Bismarck used policies favored by Socialists (such as state-sponsored healthcare) to undercut the opponents of the monarchy and protect it against revolution.

Not long after the German Revolution of 1918–1919 and signing of the Treaty of Versailles, a failed coup d'état known as the Kapp Putsch was instigated by various elements opposed to the Weimar Republic. It was led principally by Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz.

During the Weimar era, the German Realm became an ideological battlefield between "red" and "white" factions, with the state eventually becoming bifurcated between the conservative Junker nobility which dominated the army and other high offices, including the presidency with Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, and the leftist revolutionaries who attempted several coups in the 1920s and later gained a base in parliament via the Communist Party of Germany, which, being internationalist in nature, opposed the extremist nationalism of the new Nazi Party. The Nazis, by making common cause with the counterrevolutionaries against the Communists, effected a takeover of the German state, at first under the adopted imagery of the monarchical era and only later (after the death of Hindenburg) under purely Nazi imagery.

The Nazis did not publicly characterise themselves as counterrevolutionaries; they condemned the traditional German forces of conservatism (e.g., Prussian monarchists, Junkers, and Roman Catholic clergy), for example in the Nazi Party march Die Fahne hoch which labeled them as reactionaries (Reaktion) and counted them together with the Red Front as enemies of the Nazis. Nevertheless, in practice the Nazis supported many of the same ideas as the counterrevolutionary factions and virulently opposed revolutionary Marxism (e.g., using the conservative Freikorps to crush Communist uprisings), ostensibly idealising German tradition, folklore, and heroes, such as Frederick the Great. The fact that the Nazis called their 1933 rise to power the national revolution showed that they understood the popular hunger for some type of radical change; nonetheless, they understood the equally powerful popular impulse toward stability and continuity, and rejected the parliamentarianism of the Weimar Constitution as merely a first step towards Bolshevism. Thus, for instance, they catered to reactionary tendencies among the German people by propagandistic demonstrations linking the Nazi state to the traditional Reich ("realm" or "empire") by referring to it informally as the "Drittes Reich" ("Third Realm"), implying a specious continuity between it and the historic German entities appealing to German reactionaries: the Holy Roman Empire (the "First Realm") and the German Empire (the "Second Realm"). (See also reactionary modernism.)

Great Britain

Italy

In Italy, after being conquered by Napoleon's army in the late 18th century, there was a counter-revolution in all the French client republics. The most well-known was the Sanfedismo, a reactionary movement led by the cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo, which overthrew the Parthenopean Republic and allowed the Bourbon dynasty to return to the throne of the Kingdom of Naples. A resurgence of the phenomenon happened during the Napoleon's second Italian campaign in the early 19th century. Another example of counter-revolution was the peasants' rebellion in Southern Italy after the national unification, fomented by the Bourbon government in exile and the Papal States. The revolt, labelled pejoratively by opponents as brigandage, resulted in a bloody civil war that lasted almost ten years.

Austria

In the Austrian Empire, a revolt took place against Napoleon called the Tyrolean Rebellion in 1809. Led by a Tyrolean innkeeper by the name of Andreas Hofer, 20,000 Tyrolean rebels fought successfully against Napoleon's troops. However, Hofer was ultimately betrayed by the Treaty of Schönbrunn, which led to the disbandment of his troops and was captured and executed in 1810.

Spain

The Spanish Civil War was a counter-revolution. Supporters of Carlism, monarchy, and nationalism (see Falange) joined forces against the (Second) Spanish Republic in 1936. The counter-revolutionaries saw the Spanish Constitution of 1931 as a revolutionary document that defied Spanish culture, tradition and religion. On the Republican side, the acts of the Communist Party of Spain against the rural collectives are also sometimes considered counter-revolutionary. The Carlist cause began with the First Carlist War in 1833 and continues to the present.

Russia

The White Army and its supporters who tried to defeat the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution, as well as the German politicians, police, soldiers and Freikorps who crushed the German Revolution of 1918–1919, were also counter-revolutionaries. The Bolshevik government tried to build an anti-revolutionary image for the Green armies composed of peasant rebels. The largest peasant rebellion against Bolshevik rule occurred in 1920–21 in Tambov.

Hispanic America

General Victoriano Huerta, and later the Felicistas, attempted to thwart the Mexican Revolution in the 1910s. In the late 1920s, Mexican Catholics took up arms against the Mexican Federal Government in what became known as the Cristero War. The President of Mexico, Plutarco Elias Calles, was elected in 1924. Calles began carrying out anti-Catholic policies which caused peaceful resistance from Catholics in 1926. The counter-revolution began as a movement of peaceful resistance against the anti-clerical laws. In the summer of 1926, fighting broke out. The fighters known as Cristeros fought the government due to its suppression of the Church, jailing and execution of priests, formation of a nationalist schismatic church, state atheism, Socialism, Freemasonry and other harsh anti-Catholic policies.

The 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion into Cuba was conducted by counter-revolutionaries who hoped to overthrow the revolutionary government of Fidel Castro. In the 1980s, the Contra-Revolución rebels fighting to overthrow the revolutionary Sandinista government in Nicaragua. In fact, the Contras received their name precisely because they were counter-revolutionaries.

The Black Eagles, the AUC, and other paramilitary movements of Colombia can also be seen as counter-revolutionary. These right-wing groups are opposition to the FARC, and other left-wing guerrilla movements.

Some counter-revolutionaries are former revolutionaries who supported the initial overthrow of the previous regime, but came to differ with those who ultimately came to power after the revolution. For example, some of the Contras originally fought with the Sandinistas to overthrow Anastasio Somoza, and some of those who oppose Castro also opposed Batista.

Asia

Japan

During the mid-19th century Bakumatsu, especially during the Japanese civil war of 1868–1869, the pro-bakufu forces and especially the samurai (and after the period ex-samurai) were left without money since their skills are obsolete, so they banded up with the eastern shogunate led by the Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu who wished to drive foreign and especially Western European and American influence against the revolutionaries of Emperor Meiji who sought to modernize Japan with the states of Western Europe as Japan's example. The war ended with a small number of casualties, most of whom were the samurai. Years later though, western samurai and imperial modernists then engaged in the deadlier Satsuma Rebellion.

China

In 1917, during the Warlord Era general Zhang Xun attempted to reverse the 1911 Revolution that brought an end to the Qing dynasty by seizing Beijing in the Manchu Restoration.

The anti-communist (and thus counter-revolutionary) Kuomintang party in China used the term "counter-revolutionary" to disparage the communists and other opponents of its regime. Chiang Kai-shek, the Kuomintang party leader, was the chief user of this term.

The reason that the nominally conservative Kuomintang used this terminology was that the party had several leftist revolutionary influences in its ideology left over from the party's beginnings. The Kuomintang, and Chiang Kai-shek used the words "feudal" and "counter-revolutionary" as synonyms for evil, and backwardness, and proudly proclaimed themselves to be revolutionary. Chiang called the warlords feudalists, and called for feudalism and counter-revolutionaries to be stamped out by the Kuomintang. Chiang showed extreme rage when he was called a warlord, because of its negative, feudal connotations.

Chiang also crushed and dominated the merchants of Shanghai in 1927, seizing loans from them, with the threats of death or exile. Rich merchants, industrialists, and entrepreneurs were arrested by Chiang, who accused them of being "counter-revolutionary", and Chiang held them until they gave money to the Kuomintang. Chiang's arrests targeted rich millionaires, accusing them of communism and counter-revolutionary activities. Chiang also enforced an anti-Japanese boycott, sending his agents to sack the shops of those who sold Japanese made items and fining them. He also disregarded the internationally protected International Settlement, putting cages on its borders in which he threatened to place the merchants. The Kuomintang's alliance with the Green Gang allowed it to ignore the borders of the foreign concessions.

A similar term also existed in the People's Republic of China, which includes charges such collaborating with foreign forces and inciting revolts against the government and ruling CCP. According to Article 28 of the Chinese constitution, The state maintains public order and suppresses treasonable and other counter-revolutionary activities; It penalizes actions that endanger public security and disrupt the socialist economy and other criminal activities, and punishes and reforms criminals.

The term was widely used during the Cultural Revolution, in which thousands of intellectuals and government officials were denounced as "counter-revolutionaries" by the Red Guards. Following the end of the Cultural Revolution, the term was also used against Lin Biao and the Gang of Four.

Africa

Egypt

After the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak’s government as a result of the 2011 Egyptian revolution, counter revolutionary techniques included: power outages by remnants of his regime, police allegedly refused to serve citizens and oil was thrown into the desert to halt gas station services.

On 1 February 2012, the biggest tragedy in Egyptian football resulted in the deaths of 72 Al Ahly fans. It happened after exactly a year when Mubarak announced in a speech that there would be chaos if he stepped down, the very same day when armed thugs attacked protestors of the 2011 revolution. Many photographic and footage evidence also show that police and security forces in the stadium were unwilling to respond to the riot. Many argue that the riot was planned as a revenge against Ultras Ahlawy taking part in the 2011 revolution against Hosni Mubarak and their constant anti-governmental chants in matches.

Finally on 3 July 2013, Defense Minister Abdel-Fattah Al Sisi overthrew the democratically elected president Mohamed Morsi, who was the first president to be elected by the Egyptian people since the proclamation of the republic in 1953. The counter-revolution ended when Al Sisi was sworn as Egypt’s 6th president in June 2014.

Philosophical perspectives

In the Laws, Plato relates a dialogue between Cleinias of Crete and an unnamed Athenian interlocutor. Part of their discourse touches on counter-revolution. Cleinias posits that a state can be considered morally superior when the virtuous citizens triumph over the unruly masses and the less virtuous classes. He asserts, "the state in which the better citizens win a victory over the mob and over the inferior classes may be truly said to be better than itself, and may be justly praised."

However, the Athenian presents a hypothetical scenario wherein someone must pass judgment on a group of brothers, some of whom are behaving justly while others are acting unjustly. When questioned about the optimal resolution, Cleinias suggests that the most effective judge would not necessarily be one who imposes the just to govern over the unjust, whether by force or consent. Instead, he advocates for a judge who facilitates reconciliation by establishing a mutually agreed-upon set of laws designed to maintain harmony among them. This implies Cleinias' belief that a counter-revolutionary victory by the 'better citizens' over 'the mob' need not involve violence but can be attained through the enactment of just legislation.