In thermodynamics, an apparent molar property of a solution component in a mixture or solution is a quantity defined with the purpose of isolating the contribution of each component to the non-ideality of the mixture. It shows the change in the corresponding solution property (for example, volume) per mole of that component added, when all of that component is added to the solution. It is described as apparent because it appears to represent the molar property of that component in solution, provided that the properties of the other solution components are assumed to remain constant during the addition. However this assumption is often not justified, since the values of apparent molar properties of a component may be quite different from its molar properties in the pure state.

For instance, the volume of a solution containing two components identified as solvent and solute is given by

where is the volume of the pure solvent before adding the solute and its molar volume (at the same temperature and pressure as the solution), is the number of moles of solvent, is the apparent molar volume of the solute, and is the number of moles of the solute in the solution. By dividing this relation to the molar amount of one component a relation between the apparent molar property of a component and the mixing ratio of components can be obtained.

This equation serves as the definition of . The first term is equal to the volume of the same quantity of solvent with no solute, and the second term is the change of volume on addition of the solute. may then be considered as the molar volume of the solute if it is assumed that the molar volume of the solvent is unchanged by the addition of solute. However this assumption must often be considered unrealistic as shown in the examples below, so that is described only as an apparent value.

An apparent molar quantity can be similarly defined for the component identified as solvent . Some authors have reported apparent molar volumes of both (liquid) components of the same solution. This procedure can be extended to ternary and multicomponent mixtures.

Apparent quantities can also be expressed using mass instead of number of moles. This expression produces apparent specific quantities, like the apparent specific volume.

where the specific quantities are denoted with small letters.

Apparent (molar) properties are not constants (even at a given temperature), but are functions of the composition. At infinite dilution, an apparent molar property and the corresponding partial molar property become equal.

Some apparent molar properties that are commonly used are apparent molar enthalpy, apparent molar heat capacity, and apparent molar volume.

Relation to molality

The apparent (molal) volume of a solute can be expressed as a function of the molality b of that solute (and of the densities of the solution and solvent). The volume of solution per mole of solute is

Subtracting the volume of pure solvent per mole of solute gives the apparent molal volume:

For more solutes the above equality is modified with the mean molar mass of the solutes as if they were a single solute with molality bT:

- ,

The sum of products molalities – apparent molar volumes of solutes in their binary solutions equals the product between the sum of molalities of solutes and apparent molar volume in ternary of multicomponent solution mentioned above.

- ,

Relation to mixing ratio

A relation between the apparent molar of a component of a mixture and molar mixing ratio can be obtained by dividing the definition relation

to the number of moles of one component. This gives the following relation:

Relation to partial (molar) quantities

Note the contrasting definitions between partial molar quantity and apparent molar quantity: in the case of partial molar volumes , defined by partial derivatives

- ,

one can write , and so always holds. In contrast, in the definition of apparent molar volume, the molar volume of the pure solvent, , is used instead, which can be written as

- ,

for comparison. In other words, we assume that the volume of the solvent does not change, and we use the partial molar volume where the number of moles of the solute is exactly zero ("the molar volume"). Thus, in the defining expression for apparent molar volume ,

- ,

the term is attributed to the pure solvent, while the "leftover" excess volume, , is considered to originate from the solute. At high dilution with , we have , and so the apparent molar volume and partial molar volume of the solute also converge: .

Quantitatively, the relation between partial molar properties and the apparent ones can be derived from the definition of the apparent quantities and of the molality. For volume,

Relation to the activity coefficient of an electrolyte and its solvation shell number

The ratio ra between the apparent molar volume of a dissolved electrolyte in a concentrated solution and the molar volume of the solvent (water) can be linked to the statistical component of the activity coefficient of the electrolyte and its solvation shell number h:

- ,

where ν is the number of ions due to dissociation of the electrolyte, and b is the molality as above.

Examples

Electrolytes

The apparent molar volume of salt is usually less than the molar volume of the solid salt. For instance, solid NaCl has a volume of 27 cm3 per mole, but the apparent molar volume at low concentrations is only 16.6 cc/mole. In fact, some aqueous electrolytes have negative apparent molar volumes: NaOH −6.7, LiOH −6.0, and Na2CO3 −6.7 cm3/mole. This means that their solutions in a given amount of water have a smaller volume than the same amount of pure water. (The effect is small, however.) The physical reason is that nearby water molecules are strongly attracted to the ions so that they occupy less space.

Alcohol

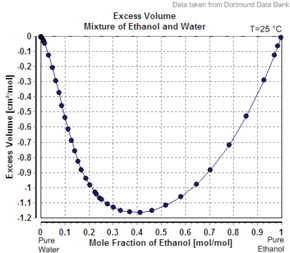

Another example of the apparent molar volume of the second component is less than its molar volume as a pure substance is the case of ethanol in water. For example, at 20 mass percents ethanol, the solution has a volume of 1.0326 liters per kg at 20 °C, while pure water is 1.0018 L/kg (1.0018 cc/g). The apparent volume of the added ethanol is 1.0326 L – 0.8 kg x 1.0018 L/kg = 0.2317 L. The number of moles of ethanol is 0.2 kg / (0.04607 kg/mol) = 4.341 mol, so that the apparent molar volume is 0.2317 L / 4.341 mol = 0.0532 L / mol = 53.2 cc/mole (1.16 cc/g). However pure ethanol has a molar volume at this temperature of 58.4 cc/mole (1.27 cc/g).

If the solution were ideal, its volume would be the sum of the unmixed components. The volume of 0.2 kg pure ethanol is 0.2 kg x 1.27 L/kg = 0.254 L, and the volume of 0.8 kg pure water is 0.8 kg x 1.0018 L/kg = 0.80144 L, so the ideal solution volume would be 0.254 L + 0.80144 L = 1.055 L. The nonideality of the solution is reflected by a slight decrease (roughly 2.2%, 1.0326 rather than 1.055 L/kg) in the volume of the combined system upon mixing. As the percent ethanol goes up toward 100%, the apparent molar volume rises to the molar volume of pure ethanol.

Electrolyte – non-electrolyte systems

Apparent quantities can underline interactions in electrolyte – non-electrolyte systems which show interactions like salting in and salting out, but also give insights in ion-ion interactions, especially by their dependence on temperature.

Multicomponent mixtures or solutions

For multicomponent solutions, apparent molar properties can be defined in several ways. For the volume of a ternary (3-component) solution with one solvent and two solutes as an example, there would still be only one equation , which is insufficient to determine the two apparent volumes. (This is in contrast to partial molar properties, which are well-defined intensive properties of the materials and therefore unambiguously defined in multicomponent systems. For example, partial molar volume is defined for each component i as .)

One description of ternary aqueous solutions considers only the weighted mean apparent molar volume of the solutes, defined as

- ,

where is the solution volume and the volume of pure water. This method can be extended for mixtures with more than 3 components.

- ,

The sum of products molalities – apparent molar volumes of solutes in their binary solutions equals the product between the sum of molalities of solutes and apparent molar volume in ternary of multicomponent solution mentioned above.

- ,

Another method is to treat the ternary system as pseudobinary and define the apparent molar volume of each solute with reference to a binary system containing both other components: water and the other solute. The apparent molar volumes of each of the two solutes are then

- and

The apparent molar volume of the solvent is:

However, this is an unsatisfactory description of volumetric properties.

The apparent molar volume of two components or solutes considered as one pseudocomponent or is not to be confused with volumes of partial binary mixtures with one common component Vij, Vjk which mixed in a certain mixing ratio form a certain ternary mixture V or Vijk.

Of course the complement volume of a component in respect to other components of the mixture can be defined as a difference between the volume of the mixture and the volume of a binary submixture of a given composition like:

There are situations when there is no rigorous way to define which is solvent and which is solute like in the case of liquid mixtures (say water and ethanol) that can dissolve or not a solid like sugar or salt. In these cases apparent molar properties can and must be ascribed to all components of the mixture.