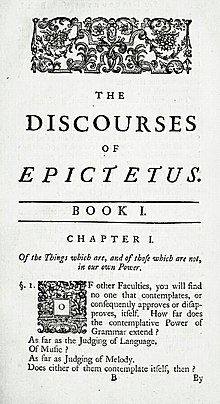

Elizabeth Carter translation, 1759 | |

| Author | Epictetus |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Discourses of Epictetus |

| Country | Greece |

| Language | Koine Greek |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date | 2nd century |

| Text | Discourses at Wikisource |

The Discourses of Epictetus (Greek: Ἐπικτήτου διατριβαί, Epiktētou diatribai) are a series of informal lectures by the Stoic philosopher Epictetus written down by his pupil Arrian around 108 AD. Four books out of an original eight are still extant. The philosophy of Epictetus is intensely practical. He directs his students to focus attention on their opinions, anxieties, passions, and desires, so that "they may never fail to get what they desire, nor fall into what they avoid." True education lies in learning to distinguish what is our own from what does not belong to us, and in learning to correctly assent or dissent to external impressions. The purpose of his teaching was to make people free and happy.

The Discourses have been influential since they were written. They are referred to and quoted by Marcus Aurelius. Since the 16th century, they have been translated into multiple languages and reprinted many times.

Title and dating

The books did not have a formal title in ancient times. Although Simplicius called them Diatribai (Διατριβαί, Discourses), other writers gave them titles such as Dialexis (Διαλέξεις, Talks), Apomnêmoneumata (Ἀπομνημονεύματα, Records), and Homiliai (Ὁμιλίαι, Conversations). The modern name comes from the titles given in the earliest medieval manuscript: "Arrian's Diatribai of Epictetus" (Greek: Ἀρριανοῦ τῶν Ἐπικτήτου Διατριβῶν). The Greek word Diatribai literally means "informal talks".

As to the date, it is generally agreed that the Discourses were composed sometime in the years around 108 AD. Epictetus himself refers to the coins of Trajan, which shows he was teaching during that reign. Arrian was suffect consul in around 130, and since forty-two was the standard age for that position, he would have been at the right age of around twenty in 108. Furthermore the "commissioner" of the "free cities" to whom Discourse iii. 7 is addressed is thought to be the same man Pliny the Younger addresses his Letter viii. 24—a letter which has been dated to around 108.

Writing

There were originally eight books, but only four now remain in their entirety, along with a few fragments of the others. In a preface attached to the Discourses, Arrian explains how he came to write them:

I neither wrote these Discourses of Epictetus in the way in which a man might write such things; nor did I make them public myself, inasmuch as I declare that I did not even write them. But whatever I heard him say, the same I attempted to write down in his own words as nearly as possible, for the purpose of preserving them as memorials to myself afterward of the thoughts and the freedom of speech of Epictetus.

— Arrian, Prefatory Letter.

The Discourses purport to be the actual words of Epictetus. They are written in Koine Greek unlike the Attic Greek Arrian uses in his own compositions. The differences in style are very marked, and they portray a vivid and separate personality. The precise method Arrian used to write the Discourses has long been a matter of vigorous debate. Extreme positions have been held ranging from the view that they are largely Arrian's own compositions to the view that Epictetus actually wrote them himself. The mainstream opinion is that the Discourses report the actual words of Epictetus, even if they cannot be a pure verbatim record. A. A. Long writes:

More likely, perhaps, he [Arrian] made his own detailed notes and used his memory to fill them out. No doubt he worked up the material into a more finished form. In some cases, he may have relied on others' reports, or checked his own record with Epictetus himself. However Arrian actually compiled the discourses, there are numerous reasons, internal to the text, for taking the gist of his record to be completely authentic to Epictetus' own style and language. These include a distinctive vocabulary, repetition of key points throughout, [and] a strikingly urgent and vivid voice quite distinct from Arrian's authorial persona in his other works.

Setting

The Discourses are set in Epictetus' own classroom in Nicopolis and they show him conversing with visitors, and reproving, exhorting, and encouraging his pupils. These pupils appear to have been young men like Arrian, of high social position and contemplating entering the public service. The Discourses are neither formal lectures nor are they part of the curriculum proper. The regular classes involved reading and interpreting characteristic portions of Stoic philosophical works, which, as well as ethics, must have included instruction in the logic and physics which were part of the Stoic system. The Discourses instead record conversations which followed the formal instruction. They dwell on points which Epictetus regarded as of special importance, and which gave him an opportunity for friendly discourse with his pupils and to discuss their personal affairs. They are not, therefore, a formal presentation of Stoic philosophy. Instead the Discourses are intensely practical. They are concerned with the conscious moral problem of right living, and how life is to be carried out well.

Themes

Three parts of philosophy

Epictetus divides philosophy into three fields of training, with especial application to ethics. The three fields, according to Epictetus, are, (1) desire (ὄρεξις); (2) choice (ὁρμή); (3) assent (συγκατάθεσις):

There are three fields of study in which people who are going to be good and excellent must first have been trained. The first has to do with desires and aversions, that they may never fail to get what they desire, nor fall into what they avoid; the second with cases of choice and of refusal, and, in general, with duty, that they may act in an orderly fashion, upon good reasons, and not carelessly; the third with the avoidance of error and rashness in judgment, and, in general, about cases of assent.

— Discourses, iii. 2. 1

The first and most essential practice is directed towards our passions and desires, which are themselves only types of impression, and as such they press and compel us. A continued practice is thus required to oppose them. To this first practice must be added a second, which is directed towards that which is appropriate (duty), and a third, the object of which is certainty and truth; but the latter must not pretend to supplant the former. Avoidance of the bad, desire for the good, the direction towards the appropriate, and the ability to assent or dissent, this is the mark of the philosopher.

Scholars disagree on whether these three fields relate to the traditional Stoic division of philosophy into Logic, Physics, and Ethics. The third field unambiguously refers to logic since it concerns valid reasoning and certainty in judgment. The second field relates to ethics, and the first field, on desires and aversions, appears to be preliminary to ethics. However Pierre Hadot has argued that this first field relates to physics since for the Stoics the study of human nature was part of the wider subject of the nature of things.

What is 'up to us'

True education lies in learning to distinguish what is our own from what does not belong to us. But there is only one thing which is fully our own: that which is our will or choice (prohairesis). The use which we make of the external impressions is our one chief concern, and upon the right kind of use depends exclusively our happiness.

Although we are not responsible for the ideas that present themselves to our consciousness, we are absolutely responsible for the way in which we use them. In the realm of judgment the truth or falsity of the external impression is to be decided. Here our concern is to assent to the true impression, reject the false, and suspend judgment regarding the uncertain. This is the act of choice. Only that which is subject to our choice is good or evil; all the rest is neither good nor evil; it concerns us not, it is beyond our reach; it is something external, merely a subject for our choice: in itself it is indifferent, but its application is not indifferent, and its application is either consistent with or contrary to nature. This choice, and consequently our opinion upon it, is in our power; in our choice we are free; nothing that is external of us, not even Zeus, can overcome our choice: it alone can control itself. Nothing external, neither death nor exile nor pain nor any such thing, can ever force us to act against our will.

Universal nature

We are bound up by the law of nature with the whole fabric of the world. In the world the true position of a human is that of a member of a great system. Each human being is in the first instance a citizen of one's own nation or commonwealth; but we are also a member of the great city of gods and people. Nature places us in certain relations to other persons, and these determine our obligations to parents, siblings, children, relatives, friends, fellow-citizens, and humankind in general. The shortcomings of our fellow people are to be met with patience and charity, and we should not allow ourselves to grow indignant over them, for they too are a necessary element in the universal system.

Providence

The universe is wholly governed by an all-wise, divine Providence. All things, even apparent evils, are the will of God, and good from the point of view of the whole. In virtue of our rationality we are neither less nor worse than the gods, for the magnitude of reason is estimated not by length nor by height but by its judgments. The aim of the philosopher therefore is to reach the position of a mind which embraces the whole world. The person who recognizes that every event is necessary and reasonable for the best interest of the whole, feels no discontent with anything outside the control of moral purpose.

The Cynic sage

The historical models to which Epictetus refers to are Socrates and Diogenes. But he describes an ideal character of a missionary sage, the perfect Stoic—or, as he calls him, the Cynic. This philosopher has neither country nor home nor land nor slave; his bed is the ground; he is without wife or child; his only home is the earth and sky and a cloak. He must suffer beatings, and must love those who beat him. The ideal human thus described will not be angry with the wrong-doer; he will only pity his erring.

Manuscript editions

The earliest manuscript of the Discourses is a twelfth-century manuscript kept at the Bodleian Library, Oxford as MS Auct. T. 4. 13. In the Bodleian manuscript, a blot or stain has fallen onto one of the pages, and has made a series of words illegible; in all the other known manuscripts these words (or sometimes the entire passage) are omitted, thus all the other manuscripts are derived from this one archetype.

It is thought that the Bodleian manuscript may be a copy of one owned by Arethas of Caesarea in the early 10th century. Arethas was an important collector of manuscripts and he is also responsible for transmitting a copy of Marcus Aurelius' Meditations. The Bodleian manuscript contains marginal notes which have been identified as by Arethas.

The manuscript is however "full of errors of all kinds".[27] Many corrections were made by medieval scholars themselves, and many emendations have been made by modern scholars to produce a clean text.

Publication history

The Discourses were first printed (in Greek) by Vettore Trincavelli, at Venice in 1535, although the manuscript used was very faulty. This was followed by editions by Jakob Schegk (1554) and Hieronymus Wolf (1560). John Upton's edition published 1739–41 was an improvement on these since he had some knowledge of several manuscripts. This in turn was improved upon by the five volume edition by Johann Schweighäuser, 1799–1800. A critical edition was produced by Heinrich Schenkl in 1894 (second edition 1916) which was based upon the Bodleian manuscript.

English translations

The first English translation did not appear until 1758 with the appearance of Elizabeth Carter's translation. This proved to be very successful, with a second edition appearing a year later (1759), a third edition in 1768, and a fourth edition published posthumously in 1807. It influenced later translations: e.g. those of Higginson and George Long (see his Introduction for comments, some critical of Carter).

A complete list of English translations is as follows:

- Elizabeth Carter, (1758), All the works of Epictetus, which are now extant; consisting of his Discourses, preserved by Arrian, in four books, the Enchiridion, and fragments. (Richardson)

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson, (1865), The Works of Epictetus. Consisting of His Discourses, in Four Books, The Enchiridion, and Fragments. (Little, Brown, and Co.)

- George Long, (1877), The Discourses of Epictetus, with the Encheridion and Fragments. (George Bell)

- Percy Ewing Matheson, (1916), Epictetus: The Discourses and Manual together with Fragments of his Writings. (Oxford University Press)

- William Abbott Oldfather, (1925–8), Discourses. (Loeb Classical Library) ISBN 0-674-99145-1 and ISBN 0-674-99240-7

- Robin Hard (translation reviser), Christopher Gill (editor), (1995), The Discourses of Epictetus. (Everyman) ISBN 0-460-87312-1

- Robert Dobbin, (2008), Discourses and Selected Writings (Penguin Classics) ISBN 0-14-044946-9

- Robin Hard, (2014), Discourses, Fragments, Handbook. (Oxford University Press) ISBN 0-199-59518-6

- Robin Waterfield, (2022), The Complete Works: Handbook, Discourses, and Fragments. (The University of Chicago Press) ISBN 9780226769332

All of these are complete translations with the exception of Robert Dobbin's book, which contains only 64 of the 95 Discourses. Robin Hard has produced two translations: the first (for Everyman in 1995) was just a revision of Elizabeth Carter's version; however, his 2014 edition (for Oxford University Press) is the first complete original translation since the 1920s.