From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alternatives to Darwinian evolution have been proposed by scholars investigating biology to explain signs of evolution and the relatedness of different groups of living things. The alternatives in question do not deny that evolutionary changes over time are the origin of the diversity of life, nor that the organisms alive today share a common ancestor from the distant past (or ancestors, in some proposals); rather, they propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change over time, arguing against mutations acted on by natural selection as the most important driver of evolutionary change.

This distinguishes them from certain other kinds of arguments that deny that large-scale evolution of any sort has taken place, as in some forms of creationism, which do not propose alternative mechanisms of evolutionary change but instead deny that evolutionary change has taken place at all. Not all forms of creationism deny that evolutionary change takes place; notably, proponents of theistic evolution, such as the biologist Asa Gray, assert that evolutionary change does occur and is responsible for the history of life on Earth, with the proviso that this process has been influenced by a god or gods in some meaningful sense.

Where the fact of evolutionary change was accepted but the mechanism proposed by Charles Darwin, natural selection, was denied, explanations of evolution such as Lamarckism, catastrophism, orthogenesis, vitalism, structuralism and mutationism (called saltationism before 1900) were entertained. Different factors motivated people to propose non-Darwinian mechanisms of evolution. Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it immoral, leaving little room for teleology or the concept of progress (orthogenesis) in the development of life. Some who came to accept evolution, but disliked natural selection, raised religious objections. Others felt that evolution was an inherently progressive process that natural selection alone was insufficient to explain. Still others felt that nature, including the development of life, followed orderly patterns that natural selection could not explain.

By the start of the 20th century, evolution was generally accepted by biologists but natural selection was in eclipse. Many alternative theories were proposed, but biologists were quick to discount theories such as orthogenesis, vitalism and Lamarckism which offered no mechanism for evolution. Mutationism did propose a mechanism, but it was not generally accepted. The modern synthesis a generation later claimed to sweep away all the alternatives to Darwinian evolution, though some have been revived as molecular mechanisms for them have been discovered.

Unchanging forms

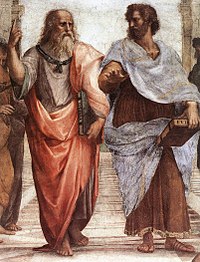

Aristotle did not embrace either divine creation or evolution, instead arguing in his biology that each species (eidos) was immutable, breeding true to its ideal eternal form (not the same as Plato's theory of forms). Aristotle's suggestion in De Generatione Animalium of a fixed hierarchy in nature - a scala naturae ("ladder of nature") provided an early explanation of the continuity of living things. Aristotle saw that animals were teleological (functionally end-directed), and had parts that were homologous with those of other animals, but he did not connect these ideas into a concept of evolutionary progress.

In the Middle Ages, Scholasticism developed Aristotle's view into the idea of a great chain of being. The image of a ladder inherently suggests the possibility of climbing, but both the ancient Greeks and mediaeval scholastics such as Ramon Lull maintained that each species remained fixed from the moment of its creation.

By 1818, however, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire argued in his Philosophie anatomique that the chain was "a progressive series", where animals like molluscs low on the chain could "rise, by addition of parts, from the simplicity of the first formations to the complication of the creatures at the head of the scale", given sufficient time. Accordingly, Geoffroy and later biologists looked for explanations of such evolutionary change.

Georges Cuvier's 1812 Recherches sur les Ossements Fossiles set out his doctrine of the correlation of parts, namely that since an organism was a whole system, all its parts mutually corresponded, contributing to the function of the whole. So, from a single bone the zoologist could often tell what class or even genus the animal belonged to. And if an animal had teeth adapted for cutting meat, the zoologist could be sure without even looking that its sense organs would be those of a predator and its intestines those of a carnivore. A species had an irreducible functional complexity, and "none of its parts can change without the others changing too". Evolutionists expected one part to change at a time, one change to follow another. In Cuvier's view, evolution was impossible, as any one change would unbalance the whole delicate system.

Louis Agassiz's 1856 "Essay on Classification" exemplified German philosophical idealism. This held that each species was complex within itself, had complex relationships to other organisms, and fitted precisely into its environment, as a pine tree in a forest, and could not survive outside those circles. The argument from such ideal forms opposed evolution without offering an actual alternative mechanism. Richard Owen held a similar view in Britain.

The Lamarckian social philosopher and evolutionist Herbert Spencer, ironically the author of the phrase "survival of the fittest" adopted by Darwin, used an argument like Cuvier's to oppose natural selection. In 1893, he stated that a change in any one structure of the body would require all the other parts to adapt to fit in with the new arrangement. From this, he argued that it was unlikely that all the changes could appear at the right moment if each one depended on random variation; whereas in a Lamarckian world, all the parts would naturally adapt at once, through a changed pattern of use and disuse.

Alternative explanations of change

Where the fact of evolutionary change was accepted by biologists but natural selection was denied, including but not limited to the late 19th century eclipse of Darwinism, alternative scientific explanations such as Lamarckism, orthogenesis, structuralism, catastrophism, vitalism and theistic evolution were entertained, not necessarily separately. (Purely religious points of view such as young or old earth creationism or intelligent design are not considered here.) Different factors motivated people to propose non-Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms. Natural selection, with its emphasis on death and competition, did not appeal to some naturalists because they felt it immoral, leaving little room for teleology or the concept of progress in the development of life. Some of these scientists and philosophers, like St. George Jackson Mivart and Charles Lyell, who came to accept evolution but disliked natural selection, raised religious objections. Others, such as the biologist and philosopher Herbert Spencer, the botanist George Henslow (son of Darwin's mentor John Stevens Henslow, also a botanist), and the author Samuel Butler, felt that evolution was an inherently progressive process that natural selection alone was insufficient to explain. Still others, including the American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Alpheus Hyatt, had an idealist perspective and felt that nature, including the development of life, followed orderly patterns that natural selection could not explain.

Some felt that natural selection would be too slow, given the estimates of the age of the earth and sun (10–100 million years) being made at the time by physicists such as Lord Kelvin, and some felt that natural selection could not work because at the time the models for inheritance involved blending of inherited characteristics, an objection raised by the engineer Fleeming Jenkin in a review of Origin written shortly after its publication. Another factor at the end of the 19th century was the rise of a new faction of biologists, typified by geneticists like Hugo de Vries and Thomas Hunt Morgan, who wanted to recast biology as an experimental laboratory science. They distrusted the work of naturalists like Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, dependent on field observations of variation, adaptation, and biogeography, as being overly anecdotal. Instead they focused on topics like physiology and genetics that could be investigated with controlled experiments in the laboratory, and discounted less accessible phenomena like natural selection and adaptation to the environment.

Vitalism

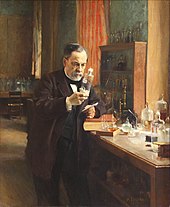

Vitalism holds that living organisms differ from other things in containing something non-physical, such as a fluid or vital spirit, that makes them live. The theory dates to ancient Egypt. Since Early Modern times, vitalism stood in contrast to the mechanistic explanation of biological systems started by Descartes. Nineteenth century chemists set out to disprove the claim that forming organic compounds required vitalist influence. In 1828, Friedrich Wöhler showed that urea could be made entirely from inorganic chemicals. Louis Pasteur believed that fermentation required whole organisms, which he supposed carried out chemical reactions found only in living things. The embryologist Hans Driesch, experimenting on sea urchin eggs, showed that separating the first two cells led to two complete but small blastulas, seemingly showing that cell division did not divide the egg into sub-mechanisms, but created more cells each with the vital capability to form a new organism. Vitalism faded out with the demonstration of more satisfactory mechanistic explanations of each of the functions of a living cell or organism. By 1931, biologists had "almost unanimously abandoned vitalism as an acknowledged belief."

Theistic evolution

The American botanist Asa Gray used the name "theistic evolution" for his point of view, presented in his 1876 book Essays and Reviews Pertaining to Darwinism. He argued that the deity supplies beneficial mutations to guide evolution. St George Jackson Mivart argued instead in his 1871 On the Genesis of Species that the deity, equipped with foreknowledge, sets the direction of evolution by specifying the (orthogenetic) laws that govern it, and leaves species to evolve according to the conditions they experience as time goes by. The Duke of Argyll set out similar views in his 1867 book The Reign of Law. According to the historian Edward Larson, the theory failed as an explanation in the minds of late 19th century biologists as it broke the rules of methodological naturalism which they had grown to expect. Accordingly, by around 1900, biologists no longer saw theistic evolution as a valid theory. In Larson's view, by then it "did not even merit a nod among scientists." In the 20th century, theistic evolution could take other forms, such as the orthogenesis of Teilhard de Chardin.

Orthogenesis

Orthogenesis or Progressionism is the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, developing in a unilinear fashion in a particular direction, or simply making some kind of definite progress. Many different versions have been proposed, some such as that of Teilhard de Chardin openly spiritual, others such as Theodor Eimer's apparently simply biological. These theories often combined orthogenesis with other supposed mechanisms. For example, Eimer believed in Lamarckian evolution, but felt that internal laws of growth determined which characteristics would be acquired and would guide the long-term direction of evolution.

Orthogenesis was popular among paleontologists such as Henry Fairfield Osborn. They believed that the fossil record showed unidirectional change, but did not necessarily accept that the mechanism driving orthogenesis was teleological (goal-directed). Osborn argued in his 1918 book Origin and Evolution of Life that trends in Titanothere horns were both orthogenetic and non-adaptive, and could be detrimental to the organism. For instance, they supposed that the large antlers of the Irish elk had caused its extinction.

Support for orthogenesis fell during the modern synthesis in the 1940s when it became apparent that it could not explain the complex branching patterns of evolution revealed by statistical analysis of the fossil record. Work in the 21st century has supported the mechanism and existence of mutation-biased adaptation (a form of mutationism), meaning that constrained orthogenesis is now seen as possible. Moreover, the self-organizing processes involved in certain aspects of embryonic development often exhibit stereotypical morphological outcomes, suggesting that evolution will proceed in preferred directions once key molecular components are in place.

Lamarckism

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's 1809 evolutionary theory, transmutation of species, was based on a progressive (orthogenetic) drive toward greater complexity. Lamarck also shared the belief, common at the time, that characteristics acquired during an organism's life could be inherited by the next generation, producing adaptation to the environment. Such characteristics were caused by the use or disuse of the affected part of the body. This minor component of Lamarck's theory became known, much later, as Lamarckism. Darwin included Effects of the increased Use and Disuse of Parts, as controlled by Natural Selection in On the Origin of Species, giving examples such as large ground feeding birds getting stronger legs through exercise, and weaker wings from not flying until, like the ostrich, they could not fly at all. In the late 19th century, neo-Lamarckism was supported by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, the American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Alpheus Hyatt, and the American entomologist Alpheus Packard. Butler and Cope believed that this allowed organisms to effectively drive their own evolution. Packard argued that the loss of vision in the blind cave insects he studied was best explained through a Lamarckian process of atrophy through disuse combined with inheritance of acquired characteristics. Meanwhile, the English botanist George Henslow studied how environmental stress affected the development of plants, and he wrote that the variations induced by such environmental factors could largely explain evolution; he did not see the need to demonstrate that such variations could actually be inherited. Critics pointed out that there was no solid evidence for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Instead, the experimental work of the German biologist August Weismann resulted in the germ plasm theory of inheritance, which Weismann said made the inheritance of acquired characteristics impossible, since the Weismann barrier would prevent any changes that occurred to the body after birth from being inherited by the next generation.

In modern epigenetics, biologists observe that phenotypes depend on heritable changes to gene expression that do not involve changes to the DNA sequence. These changes can cross generations in plants, animals, and prokaryotes. This is not identical to traditional Lamarckism, as the changes do not last indefinitely and do not affect the germ line49 and hence the evolution of genes.

Catastrophism

Catastrophism is the hypothesis, argued by the French anatomist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier in his 1812 Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes, that the various extinctions and the patterns of faunal succession seen in the fossil record were caused by large-scale natural catastrophes such as volcanic eruptions and, for the most recent extinctions in Eurasia, the inundation of low-lying areas by the sea. This was explained purely by natural events: he did not mention Noah's flood, nor did he ever refer to divine creation as the mechanism for repopulation after an extinction event, though he did not support evolutionary theories such as those of his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire either. Cuvier believed that the stratigraphic record indicated that there had been several such catastrophes, recurring natural events, separated by long periods of stability during the history of life on earth. This led him to believe the Earth was several million years old.

Catastrophism has found a place in modern biology with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period, as proposed in a paper by Walter and Luis Alvarez in 1980. It argued that a 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period. The event, whatever it was, made about 70% of all species extinct, including the dinosaurs, leaving behind the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. In 1990, a 180 kilometres (110 mi) candidate crater marking the impact was identified at Chicxulub in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico.

Structuralism

Biological structuralism objects to an exclusively Darwinian explanation of natural selection, arguing that other mechanisms also guide evolution, and sometimes implying that these supersede selection altogether. Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation of body plans. Before Darwin, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire argued that animals shared homologous parts, and that if one was enlarged, the others would be reduced in compensation. After Darwin, D'Arcy Thompson hinted at vitalism and offered geometric explanations in his classic 1917 book On Growth and Form. Adolf Seilacher suggested mechanical inflation for "pneu" structures in Ediacaran biota fossils such as Dickinsonia. Günter P. Wagner argued for developmental bias, structural constraints on embryonic development. Stuart Kauffman favoured self-organisation, the idea that complex structure emerges holistically and spontaneously from the dynamic interaction of all parts of an organism. Michael Denton argued for laws of form by which Platonic universals or "Types" are self-organised. In 1979 Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin proposed biological "spandrels", features created as a byproduct of the adaptation of nearby structures. Gerd Müller and Stuart Newman argued that the appearance in the fossil record of most of the current phyla in the Cambrian explosion was "pre-Mendelian" evolution caused by plastic responses of morphogenetic systems that were partly organized by physical mechanisms. Brian Goodwin, described by Wagner as part of "a fringe movement in evolutionary biology", denied that biological complexity can be reduced to natural selection, and argued that pattern formation is driven by morphogenetic fields. Darwinian biologists have criticised structuralism, emphasising that there is plentiful evidence from deep homology that genes have been involved in shaping organisms throughout evolutionary history. They accept that some structures such as the cell membrane self-assemble, but question the ability of self-organisation to drive large-scale evolution.

Saltationism, mutationism

Saltationism held that new species arise as a result of large mutations. It was seen as a much faster alternative to the Darwinian concept of a gradual process of small random variations being acted on by natural selection. It was popular with early geneticists such as Hugo de Vries, who along with Carl Correns helped rediscover Gregor Mendel's laws of inheritance in 1900, William Bateson, a British zoologist who switched to genetics, and early in his career, Thomas Hunt Morgan. These ideas developed into mutationism, the mutation theory of evolution. This held that species went through periods of rapid mutation, possibly as a result of environmental stress, that could produce multiple mutations, and in some cases completely new species, in a single generation, based on de Vries's experiments with the evening primrose, Oenothera, from 1886. The primroses seemed to be constantly producing new varieties with striking variations in form and color, some of which appeared to be new species because plants of the new generation could only be crossed with one another, not with their parents. However, Hermann Joseph Muller showed in 1918 that the new varieties de Vries had observed were the result of polyploid hybrids rather than rapid genetic mutation.

Initially, de Vries and Morgan believed that mutations were so large as to create new forms such as subspecies or even species instantly. Morgan's 1910 fruit fly experiments, in which he isolated mutations for characteristics such as white eyes, changed his mind. He saw that mutations represented small Mendelian characteristics that would only spread through a population when they were beneficial, helped by natural selection. This represented the germ of the modern synthesis, and the beginning of the end for mutationism as an evolutionary force.

Contemporary biologists accept that mutation and selection both play roles in evolution; the mainstream view is that while mutation supplies material for selection in the form of variation, all non-random outcomes are caused by natural selection. Masatoshi Nei argues instead that the production of more efficient genotypes by mutation is fundamental for evolution, and that evolution is often mutation-limited. The endosymbiotic theory implies rare but major events of saltational evolution by symbiogenesis. Carl Woese and colleagues suggested that the absence of RNA signature continuum between domains of bacteria, archaea, and eukarya shows that these major lineages materialized via large saltations in cellular organization. Saltation at a variety of scales is agreed to be possible by mechanisms including polyploidy, which certainly can create new species of plant, gene duplication, lateral gene transfer, and transposable elements (jumping genes).

Genetic drift

The neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura in 1968, holds that at the molecular level most evolutionary changes and most of the variation within and between species is not caused by natural selection but by genetic drift of mutant alleles that are neutral. A neutral mutation is one that does not affect an organism's ability to survive and reproduce. The neutral theory allows for the possibility that most mutations are deleterious, but holds that because these are rapidly purged by natural selection, they do not make significant contributions to variation within and between species at the molecular level. Mutations that are not deleterious are assumed to be mostly neutral rather than beneficial.

The theory was controversial as it sounded like a challenge to Darwinian evolution; controversy was intensified by a 1969 paper by Jack Lester King and Thomas H. Jukes, provocatively but misleadingly titled "Non-Darwinian Evolution". It provided a wide variety of evidence including protein sequence comparisons, studies of the Treffers mutator gene in E. coli, analysis of the genetic code, and comparative immunology, to argue that most protein evolution is due to neutral mutations and genetic drift.

According to Kimura, the theory applies only for evolution at the molecular level, while phenotypic evolution is controlled by natural selection, so the neutral theory does not constitute a true alternative.

Combined theories

The various alternatives to Darwinian evolution by natural selection were not necessarily mutually exclusive. The evolutionary philosophy of the American palaeontologist Edward Drinker Cope is a case in point. Cope, a religious man, began his career denying the possibility of evolution. In the 1860s, he accepted that evolution could occur, but, influenced by Agassiz, rejected natural selection. Cope accepted instead the theory of recapitulation of evolutionary history during the growth of the embryo - that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, which Agassiz believed showed a divine plan leading straight up to man, in a pattern revealed both in embryology and palaeontology. Cope did not go so far, seeing that evolution created a branching tree of forms, as Darwin had suggested. Each evolutionary step was however non-random: the direction was determined in advance and had a regular pattern (orthogenesis), and steps were not adaptive but part of a divine plan (theistic evolution). This left unanswered the question of why each step should occur, and Cope switched his theory to accommodate functional adaptation for each change. Still rejecting natural selection as the cause of adaptation, Cope turned to Lamarckism to provide the force guiding evolution. Finally, Cope supposed that Lamarckian use and disuse operated by causing a vitalist growth-force substance, "bathmism", to be concentrated in the areas of the body being most intensively used; in turn, it made these areas develop at the expense of the rest. Cope's complex set of beliefs thus assembled five evolutionary philosophies: recapitulationism, orthogenesis, theistic evolution, Lamarckism, and vitalism. Other palaeontologists and field naturalists continued to hold beliefs combining orthogenesis and Lamarckism until the modern synthesis in the 1930s.

Rebirth of natural selection, with continuing alternatives

By the start of the 20th century, during the eclipse of Darwinism, biologists were doubtful of natural selection, but equally were quick to discount theories such as orthogenesis, vitalism and Lamarckism which offered no mechanism for evolution. Mutationism did propose a mechanism, but it was not generally accepted. The modern synthesis a generation later, roughly between 1918 and 1932, broadly swept away all the alternatives to Darwinism, though some including forms of orthogenesis, epigenetic mechanisms that resemble Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics, catastrophism, structuralism, and mutationism have been revived, such as through the discovery of molecular mechanisms.

Biology has become Darwinian, but belief in some form of progress (orthogenesis) remains both in the public mind and among biologists. Ruse argues that evolutionary biologists will probably continue to believe in progress for three reasons. Firstly, the anthropic principle demands people able to ask about the process that led to their own existence, as if they were the pinnacle of such progress. Secondly, scientists in general and evolutionists in particular believe that their work is leading them progressively closer to a true grasp of reality, as knowledge increases, and hence (runs the argument) there is progress in nature also. Ruse notes in this regard that Richard Dawkins explicitly compares cultural progress with memes to biological progress with genes. Thirdly, evolutionists are self-selected; they are people, such as the entomologist and sociobiologist E. O. Wilson, who are interested in progress to supply a meaning for life.