Universal jurisdiction is a legal principle that allows states or international organizations to claim criminal jurisdiction over an accused person regardless of where the alleged crime was committed, and regardless of the accused's nationality, country of residence, or any other relation to the prosecuting entity. Crimes prosecuted under universal jurisdiction are considered crimes against all, too serious to tolerate jurisdictional arbitrage. The concept of universal jurisdiction is therefore closely linked to the idea that some international norms are erga omnes, or owed to the entire world community, as well as to the concept of jus cogens – that certain international law obligations are binding on all states.

According to Amnesty International, a proponent of universal jurisdiction, certain crimes pose so serious a threat to the international community as a whole that states have a logical and moral duty to prosecute an individual responsible; therefore, no place should be a safe haven for those who have committed genocide, crimes against humanity, extrajudicial executions, war crimes, torture, or forced disappearances.

Opponents such as Henry Kissinger, who himself was called to give testimony about the U.S. government's Operation Condor in a Spanish court, argue that universal jurisdiction is a breach of each state's sovereignty: all states being equal in sovereignty, as affirmed by the United Nations Charter, "[w]idespread agreement that human rights violations and crimes against humanity must be prosecuted has hindered active consideration of the proper role of international courts. Universal jurisdiction risks creating universal tyranny – that of judges." According to Kissinger, as a logistical matter, since any number of states could set up such universal jurisdiction tribunals, the process could quickly degenerate into politically driven show trials to attempt to place a quasi-judicial stamp on a state's enemies or opponents.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006, "Reaffirm[ed] the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity" and commits the Security Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

History

The Institutes of Justinian, echoing the Commentaries of Gaius, says that "All nations ... are governed partly by their own particular laws, and partly by those laws which are common to all, [those that] natural Reason appoints for all mankind." Expanding on the classical understanding of universal law accessible by reason, in the seventeenth century, the Dutch jurist Grotius laid the foundations for universal jurisdiction in modern international law, promulgating in his De Jure Praedae (Of the Law of Captures) and later Dē jūre bellī ac pācis (Of the Law of War and Peace) the Enlightenment view that there are universal principles of right and wrong.

According to Henry Kissinger, at about the same time, international law came to recognize the analogous concept of hostēs hūmānī generis ("enemies of the human race") applying to pirates or hijackers whose crimes took place outside of nation-state territories, while universal jurisdiction subjecting senior officials or heads of states as criminal subjects was new.

From these premises, representing the Enlightenment belief in trans-territorial, trans-cultural standards of right and wrong, derives universal jurisdiction.

Perhaps the most notable and influential precedent for universal jurisdiction were the mid-20th century Nuremberg Trials. U.S. Justice Robert H. Jackson then chief prosecutor, famously stated that an International Military Tribunal enforcing universal principles of right and wrong could prosecute acts without a particular geographic location, Nazi "crimes against the peace of the world"—even if the acts were perfectly legal at the time in Fascist Germany. Indeed, one charge was Nazi law itself became a crime, law distorted into a bludgeon of oppression. The Nuremberg trials supposed universal standards by which one nation's laws, and acts of its officials, can be judged; an international rule of law unbound by national borders.

On the other hand, even at the time, the Nuremberg trials were criticized as victor's justice, revenge papered over with legal simulacra. US Supreme Court Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone remarked that his colleague Justice Jackson acting as Nuremberg Chief prosecutor was "conducting his high-grade lynching party in Nuremberg. I don't mind what he does to the Nazis, but I hate to see the pretense that he is running a court and proceeding according to common law. This is a little too sanctimonious a fraud to meet my old-fashioned ideas."

Kenneth Roth, the executive director of Human Rights Watch, argues that universal jurisdiction allowed Israel to try Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961. Roth also argues that clauses in treaties such as the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the United Nations Convention Against Torture of 1984, which requires signatory states to pass municipal laws that are based on the concept of universal jurisdiction, indicate widespread international acceptance of the concept.

Theory of universal jurisdiction application

Amongst the vast spread of literature surrounding the theory, application, and history of Universal Jurisdiction, there are two approaches: the "global enforcer" and the "no safe haven". "Global enforcer" refers to the usage of Universal Jurisdiction as an active way of preventing and punishing international crimes committed anywhere while "no safe haven" takes on a more passive tone, referring to the usage of this principle to ensure that the specific country is not a territorial refuge for any suspects of international crimes.

Universal distinct from extraterritorial jurisdiction

Universal jurisdiction differs from a state's prosecuting crimes under its own laws, whether on its own territory (territorial jurisdiction) or abroad (extraterritorial jurisdiction). As an example, the United States asserts jurisdiction over stateless vessels carrying illicit drugs on international waters—but here the US reaches across national borders to enforce its own law, rather than invoking universal jurisdiction and trans-national standards of right and wrong.

States attempting to police acts committed by foreign nationals on foreign territory tends to be more controversial than a state prosecuting its own citizens wherever they may be found. Bases on which a state might exercise jurisdiction in this way include the following:

- A state can exercise jurisdiction over acts that affect the fundamental interests of the state, such as spying, even if the act was committed by foreign nationals on foreign territory. For example, the Indian Information Technology Act 2000 largely supports the extraterritoriality of the said Act. The law states that a contravention of the Act that affects any computer or computer network situated in India will be punishable by India irrespective of the culprit's location and nationality.

- A state may try its own nationals for crimes committed abroad. France and some other nations will refuse to extradite their own citizens as a matter of law, but will instead try them on their own territory for crimes committed abroad.

- More controversial is the exercise of jurisdiction where the victim of the crime is a national of the state exercising jurisdiction. In the past some states have claimed this jurisdiction (e.g., Mexico, Cutting Case (1887)), while others have been strongly opposed to it (e.g., the United States, except in cases in which an American citizen is a victim: US v Yunis (1988)). In more recent years, however, a broad global consensus has emerged in permitting its use in the case of torture, "forced disappearances" or terrorist offences (due in part to it being permitted by the various United Nations conventions on terrorism); but its application in other areas is still highly controversial. For example, former dictator of Chile Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998, on Spanish judge Baltazar Garzon's demand, on charges of human rights abuses, not on the grounds of universal jurisdiction but rather on the grounds that some of the victims of the abuses committed in Chile were Spanish citizens. Spain then sought his extradition from Britain, again, not on the grounds of universal jurisdiction, but by invoking the law of the European Union regarding extradition; and he was finally released on grounds of health. Argentinian Alfredo Astiz's sentence is part of this juridical frame.

International tribunals invoking universal jurisdiction

Established in The Hague in 2002, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is an international tribunal of general jurisdiction (defined by treaty) to prosecute state-members' citizens for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression, as specified by several international agreements, most prominently the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court signed in 1998. A serious international crime is outlined in Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal court as a serious criminal act committed as part of a "widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack", including murder, rape, slavery, persecution, extermination, and torture. Universal jurisdiction over the crimes enumerated in the Rome Statute was rejected by the signing parties, however universal jurisdiction is what allows the United Nations Security Council to refer specific situations to the ICC. This has only happened with Darfur (2005) and Libya (2011).

In addition the United Nations has set up geographically specific courts to investigate and prosecute crimes against humanity under a theory of universal jurisdiction, such as the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994), and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993).

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia investigates war crimes that took place in the Balkans in the 1990s. It convicted former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić on 10 charges relating to directing murders, purges and other abuses against civilians, including genocide in connection with the 1995 massacre of 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica; he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Particular states invoking universal jurisdiction

Universal jurisdiction may be asserted by a particular nation as well as by an international tribunal. The result is the same: individuals become answerable for crimes defined and prosecuted regardless of where they live, or where the conduct occurred; crimes said to be so grievous as to be universally condemned.

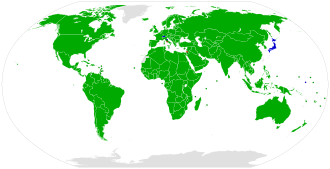

Amnesty International argues that since the end of the Second World War over fifteen states have conducted investigations, commenced prosecutions and completed trials based on universal jurisdiction for the crimes or arrested people with a view to extraditing the persons to a state seeking to prosecute them. These states include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Mexico, Netherlands, Senegal, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Amnesty writes:

All states parties to the Convention against Torture and the Inter-American Convention are obliged whenever a person suspected of torture is found in their territory to submit the case to their prosecuting authorities for the purposes of prosecution, or to extradite that person. In addition, it is now widely recognized that states, even those that are not states parties to these treaties, may exercise universal jurisdiction over torture under customary international law.

Examples of particular states invoking universal jurisdiction are Israel's prosecution of Eichmann in 1961 (see § Israel below) and Spain's prosecution of South American dictators and torturers (see § Spain below). More recently, the Center for Constitutional Rights tried first in Switzerland and then in Canada to prosecute former U.S. President George W. Bush on behalf of persons tortured in US detention camps, invoking the universal jurisdiction doctrine. Bush cancelled his trip to Switzerland after news of the planned prosecution came to light. Bush has traveled to Canada but the Canadian government shut down the prosecution in advance of his arrest. The center has filed a grievance with the United Nations for Canada's failure to invoke universal jurisdiction to enforce the Convention Against Torture, a petition on which action is pending.

Immunity for state officials

On 14 February 2002, the International Court of Justice in the ICJ Arrest Warrant Case concluded that state officials may have immunity under international law while serving in office. The court stated that immunity was not granted to state officials for their own benefit, but instead to ensure the effective performance of their functions on behalf of their respective states. The court also stated that when abroad, state officials may enjoy immunity from arrest in another state on criminal charges, including charges of war crimes or crimes against humanity. But the ICJ qualified its conclusions, saying that state officers "may be subject to criminal proceedings before certain international criminal courts, where they have jurisdiction. Examples include the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda ..., and the future International Criminal Court."

In 2003, Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, was served with an arrest warrant by the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) that was set up under the auspices of a treaty that binds only the United Nations and the Government of Sierra Leone. Taylor contested the Special Court's jurisdiction, claiming immunity, but the Special Court for Sierra Leone concluded in 2004 that "the sovereign equality of states does not prevent a head of state from being prosecuted before an international criminal tribunal or court". The Special Court convicted Taylor in 2012 and sentenced him to fifty years' imprisonment, making him the first head of state since the Nuremberg trials after World War II to be tried and convicted by an international court. In sum, the question whether a former head of state might have immunity depends on which international court or tribunal endeavors to try him, how the court is constituted, and how it interprets its own mandate.

Universal jurisdiction enforcement around the world

Australia

The High Court of Australia confirmed the authority of the Australian Parliament, under the Australian Constitution, to exercise universal jurisdiction over war crimes in the Polyukhovich v Commonwealth case of 1991.

Belgium

In 1993, Belgium's Parliament passed a "law of universal jurisdiction" (sometimes referred to as "Belgium's genocide law"), allowing it to judge people accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide. In 2001, four Rwandan citizens were convicted and given sentences from 12 to 20 years' imprisonment for their involvement in 1994 Rwandan genocide. There was a rapid succession of cases:

- Prime Minister Ariel Sharon was accused of involvement in the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon, conducted by a Christian militia;

- Israelis filed a case against Yasser Arafat on grounds of responsibility for terrorist activity;

- In 2003, Iraqi victims of a 1991 Baghdad bombing pressed charges against George H. W. Bush, Colin Powell, and Dick Cheney.

Confronted with this sharp increase in cases, Belgium established the condition that the accused person must be Belgian or present in Belgium. An arrest warrant issued in 2000 under this law, against the then Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Abdoulaye Yerodia Ndombasi, was challenged before the International Court of Justice in the case entitled ICJ Arrest Warrant Case. The ICJ's decision issued on 14 February 2002 found that it did not have jurisdiction to consider the question of universal jurisdiction, instead deciding the question on the basis of immunity of high-ranking state officials. However, the matter was addressed in separate and dissenting opinions, such as that of President Guillaume who concluded that universal jurisdiction exists only in relation to piracy; and the dissenting opinion of Judge Oda who recognised piracy, hijacking, terrorism and genocide as crimes subject to universal jurisdiction.

On 1 August 2003, Belgium repealed the law on universal jurisdiction, and introduced a new law on extraterritorial jurisdiction similar to or more restrictive than that of most other European countries. However, some cases that had already started continued. These included those concerning the Rwandan genocide, and complaints filed against the Chadian ex-President Hissène Habré (dubbed the "African Pinochet"). In September 2005, Habré was indicted for crimes against humanity, torture, war crimes and other human rights violations by a Belgian court. Arrested in Senegal following requests from Senegalese courts, he was tried and convicted for war crimes by the Special Tribunal in Senegal in 2016 and sentenced to life in prison.

Canada

To implement the Rome Statute, Canada passed the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act. Michael Byers, a University of British Columbia law professor, has argued that these laws go further than the Rome Statute, providing Canadian courts with jurisdiction over acts pre-dating the ICC and occurring in territories outside of ICC member-states; "as a result, anyone who is present in Canada and alleged to have committed genocide, torture ... anywhere, at any time, can be prosecuted [in Canada]".

Finland

François Bazaramba was sentenced to life imprisonment in Finland in 2010 for participation in the Rwandan genocide of 1994.

In 2021 a trial for Gibril Massaquoi, charged with murder, aggravated war crimes and aggravated crimes against humanity in Liberia, started in Finland, with part of the hearings of witnesses to take place in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

France

The article 689 of the code de procédure pénale states the infractions that can be judged in France when they were committed outside French territory either by French citizens or foreigners. The following infractions may be prosecuted:

- Torture

- Terrorism

- Nuclear smuggling

- Naval piracy

- Airplane hijacking

In February 2019, Abdulhamid Chaban, a former soldier of the Syrian Army was arrested and indicted for complicity in crimes against humanity during the Syrian civil war, whereas Majdi Nema, a former spokesperson for Jaysh al-Islam, was arrested and indicted for war crimes and torture, respectively. In May 2023, the French Court of Cassation ruled that French universal jurisdiction allows for a trial of said individuals, and that it was not obligatory that "the offences of crime against humanity or war crime be identically described by the laws of the foreign country", in this case Syria.

On 15 November 2023, France issued international arrest warrants for Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad and three other Syrian officials for war crimes perpetrated during the 2013 Ghouta chemical attack and the 2018 Douma chemical attack.

Germany

Under the German legal system, international crimes are offenses that require public prosecution (Offizialdelikte) and are not dependent on the victims' individual criminal complaints to initiate the prosecution.

Nikola Jorgić on 26 September 1997 was convicted of genocide in Germany and sentenced to four terms of life imprisonment for his involvement in the Bosnian genocide. His appeal following his conviction was rejected by the German Federal Court of Justice, Germany's highest court of appeal for criminal matters, on 30 April 1999. The court stated that genocide is a crime which all nations must prosecute.

Since then Germany has implemented the principle of universal jurisdiction for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes into its criminal law through the Völkerstrafgesetzbuch or VStGB ("international criminal code", literally "book of the criminal law of peoples"), which implemented the treaty creating the International Criminal Court into domestic law. The law was passed in 2002 and up to 2014. It has been used once, in the trial of Rwandan rebel leader Ignace Murwanashyaka. In 2015 he was found guilty and sentenced to 13 years in prison. Furthermore, section 7(2) of German Criminal Code Strafgesetzbuch (stGB) establishes the principle of aut dedere aut judicare, stating that German criminal law applies to offenses committed abroad by foreign nationals who currently reside in Germany if there is no criminal law jurisdiction in the foreign country or when no extradition request was made.

Ireland

Israel

The moral philosopher Peter Singer, along with Kenneth Roth, has cited Israel's prosecution of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 as an assertion of universal jurisdiction. He claims that while Israel did invoke a statute specific to Nazi crimes against Jews, its Supreme Court claimed universal jurisdiction over crimes against humanity.

Eichmann's defense lawyer argued that Israel did not have jurisdiction on account of Israel not having come into existence until 1948. The Genocide Convention also did not come into effect until 1951, and the Genocide Convention does not automatically provide for universal jurisdiction. It is also argued that Israeli agents obtained Eichmann illegally, violating international law when they seized and kidnapped Eichmann, and brought him to Israel to stand trial. The Argentinian government settled the dispute diplomatically with Israel.

Israel argued universal jurisdiction based on the "universal character of the crimes in question" and that the crimes committed by Eichmann were not only in violation of Israel law, but were considered "grave offenses against the law of nations itself". It also asserted that the crime of genocide is covered under international customary law. As a supplemental form of jurisdiction, a further argument is made on the basis of protective jurisdiction. Protective jurisdiction is a principle that "provides that states may exercise jurisdiction over aliens who have committed an act abroad which is deemed prejudicial to the security of the particular state concerned".

Malaysia

In November 2011, the Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Commission (KLWCC), created in 2007 by former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad as a private institution (without the support of any government), exercised what it viewed as universal jurisdiction to try and convict in absentia former US President George W. Bush and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair for the invasion of Iraq. In May 2012, the tribunal again under what it saw as universal jurisdiction took testimony from victims of torture at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, and convicted in absentia former President Bush, former Vice President Dick Cheney, former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, former Deputy Assistant Attorneys General John Yoo and Jay Bybee, former Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, and former counselors David Addington and William Haynes II for conspiracy to commit war crimes. The tribunal referred its findings to the chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

The Malaysian human rights group SUARAM expressed concern about the KLWCC's procedures, and former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, Param Cumaraswamy, described the KLWCC as having no legal basis, and was sceptical about fair trials taking place in absentia.

Netherlands

In January 2024, Mustafa A., a member of Liwa al-Quds, was convicted in the Netherlands for war crimes and crimes against humanity carried out during the Syrian civil war while fighting on the side of Syrian government forces. He was sentenced to twelve years of imprisonment.

Senegal

A case against the former dictator of Chad, Hissène Habré, started in 2015 in Senegal.

Spain

Spanish law recognizes the principle of universal jurisdiction. Article 23.4 of the Judicial Power Organization Act (LOPJ), enacted on 1 July 1985, establishes that Spanish courts have jurisdiction over crimes committed by Spaniards or foreign citizens outside Spain when such crimes can be described according to Spanish criminal law as genocide, terrorism, or some other, as well as any other crime that, according to international treaties or conventions, must be prosecuted in Spain. On 25 July 2009, the Spanish Congress passed a law that limits the competence of the Audiencia Nacional under Article 23.4 to cases in which Spaniards are victims, there is a relevant link to Spain, or the alleged perpetrators are in Spain. The law still has to pass the Senate, the high chamber, but passage is expected because it is supported by both major parties.

In 1999, Nobel Peace Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú brought a case against the Guatemalan military leadership in a Spanish Court. Six officials, among them Efraín Ríos Montt and Óscar Humberto Mejía, were formally charged on 7 July 2006 to appear in the Spanish National Court after Spain's Constitutional Court ruled in September 2005, the Spanish Constitutional Court declaration that the "principle of universal jurisdiction prevails over the existence of national interests", following the Menchu suit brought against the officials for atrocities committed in the Guatemalan Civil War.

In June 2003, Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón jailed Ricardo Miguel Cavallo, a former Argentine naval officer, who was extradited from Mexico to Spain pending his trial on charges of genocide and terrorism relating to the years of Argentina's military dictatorship.

On 11 January 2006, the Spanish High Court agreed to investigate a case in which seven former Chinese officials, including the former Communist Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin and former Premier Li Peng were alleged to have participated in a genocide in Tibet. This investigation follows a Spanish Constitutional Court (26 September 2005) ruling that Spanish courts could try genocide cases even if they did not involve Spanish nationals. China denounced the investigation as an interference in its internal affairs and dismissed the allegations as "sheer fabrication". The case was shelved in 2010, because of a law passed in 2009 that restricted High Court investigations to those "involving Spanish victims, suspects who are in Spain, or some other obvious link with Spain".

Complaints were lodged against former Israeli Defense Forces chief of General Staff Lt.-Gen. (res.) Dan Halutz and six other senior Israeli political and military officials by pro-Palestinian organizations, who sought to prosecute them in Spain under the principle of universal jurisdiction. On 29 January 2009, Fernando Andreu, a judge of the Audiencia Nacional, opened preliminary investigations into claims that a targeted killing attack in Gaza in 2002 warranted the prosecution of Halutz, the former Israeli defence minister Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, the former defence chief-of-staff Moshe Ya'alon, and four others, for crimes against humanity. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu strongly criticized the decision, and Israeli officials refused to provide information requested by the Spanish court. The attack killed the founder and leader of the military wing of the Islamic militant organisation Hamas, Salah Shehade, who Israel said was responsible for hundreds of civilian deaths. The attack also killed 14 others (including his wife and 9 children). It had targeted the building where Shahade hid in Gaza City. It also wounded some 150 Palestinians, according to the complaint (or 50, according to other reports). The Israeli chief of operations and prime minister apologized officially, saying they were unaware, due to faulty intelligence, that civilians were in the house. The investigation in the case was halted on 30 June 2009 by a decision of a panel of 18 judges of the Audiencia Nacional. The Spanish Court of Appeals rejected the lower court's decision, and on appeal in April 2010 the Supreme Court of Spain upheld the Court of Appeals decision against conducting an official inquiry into the IDF's targeted killing of Shehadeh.

Sweden

Universal jurisdiction was used in Sweden for the trial of Hamid Nouri for involvement in the 1988 executions of Iranian political prisoners. In 2022, Nouri was sentenced to a life in prison.

In April 2024, a Swedish court started a trial of Syrian Brigadier general Mohammed Hamo for indiscriminate attacks against civilians in Homs during the Syrian civil war.

Switzerland

On 18 June 2021, former ULIMO commander Alieu Kosiah was sentenced to 20 years in prison for committing war crimes in Liberia during the country's first civil war. This was the first time that a Liberian national was tried for war crimes in relation to the Liberian Civil Wars, and the first time that the Swiss Federal Criminal Court held a war crimes trial.

On 18 April 2023, the Swiss Attorney General declared that Ousman Sonko, a former Interior Minister of the Gambia, had been charged with crimes against humanity. He was accused of "having supported, participated in and failed to prevent 'systematic and generalised attacks' as part of a repressive campaign by security forces against Jammeh's opponents".

Turkey

In January 2022, when filing a criminal case in the Istanbul Prosecutor's Office against Chinese officials for torture, rape, crimes against humanity and genocide against Uyghurs, lawyer Gulden Sonmez stated that Turkish legislation recognises universal jurisdiction for these offences.

United Kingdom

An offence is generally only triable in the jurisdiction where the offence took place, unless a specific statute enables the UK to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction. This is the case, inter alia, for:

- Torture (s. 134 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988)

- Sexual offences against children (s. 72 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, formerly Sexual Offences Act 1956)

- Fraud and dishonesty (Criminal Justice Act 1993 Part 1)

- Terrorism (ss. 59, 62–63 of the Terrorism Act 2000)

- Bribery (was s. 109 of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, now s. 12 of the Bribery Act 2010)

- Human trafficking and sexual exploitation (s. 2 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015, ss. 52–54 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, and several earlier acts)

In December 2009, Westminster Magistrates' Court issued an arrest warrant for Tzipi Livni in connection with accusations of war crimes in the Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead (2008–2009). The warrant was issued on 12 December and revoked on 14 December 2009 after it was revealed that Livni had not entered British territory. The warrant was later denounced as "cynical" by the Israeli foreign ministry, while Livni's office said she was "proud of all her decisions in Operation Cast Lead". Livni herself called the arrest warrant "an abuse of the British legal system". Similarly a January visit to Britain by a team of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) was cancelled over concerns that arrest warrants would be sought by pro-Palestinian advocates in connection with allegations of war crimes under laws of universal jurisdiction.

In January 2013, Nepalese Colonel Kumar Lama was charged in the UK with torture under universal jurisdiction. He was acquitted in September 2016, with the jury finding him not guilty on one count, and failing to reach a verdict on the other.

United States

The United States has no formal statute to authorize it. In some cases, however, the federal government has exercised self-help in the apprehension or killing persons who are suspected of conspiring to commit crimes within the United States from outside of the country or committing crimes against American officials outside of the United States. This has occurred even when the suspect is not a United States person, has never been to the United States, and even when the person has never conspired or assisted in the commission of a crime within the United States, there is a functioning government which could try the person for the crime committed there, and notwithstanding the existence of a proper treaty of extradition between that country and the United States, ignoring the provisions of the treaty and capturing or killing the person directly.

In 1985, the Mexican national Humberto Alvarez-Machain allegedly assisted in the torture and murder of a United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent in Mexico. Mexico declined to extradite a Mexican national for the alleged crime committed in Mexico, despite having a treaty of extradition. The United States then hired a private citizen and some Mexican nationals as mercenaries to kidnap Alvarez-Machain and take him to the United States for trial. The trial court ruled that his arrest was unlawful because it violated the extradition treaty. On appeal, in United States v. Alvarez-Machain, 504 U.S. 655 (1992), the Supreme Court held that, notwithstanding the existence of an extradition treaty with Mexico, it was still legal for the federal government of the United States to exercise self-help by forcibly abducting him on a street in Mexico and bringing him to the United States to stand trial. In Alvarez-Machain's subsequent criminal trial, he was acquitted; he later lost a lawsuit against the American government over his wrongful apprehension and imprisonment.

By event

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

Universal jurisdiction investigations of war crimes in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine were started under universal jurisdiction legislation of several individual states. States that started investigations included Germany, Lithuania, Spain and Sweden.