Liquefied petroleum gas, also referred to as liquid petroleum gas (LPG or LP gas), is a fuel gas which contains a flammable mixture of hydrocarbon gases, specifically propane, n-butane and isobutane. It can sometimes contain some propylene, butylene, and isobutene.

LPG is used as a fuel gas in heating appliances, cooking equipment, and vehicles. It is increasingly used as an aerosol propellant and a refrigerant, replacing chlorofluorocarbons in an effort to reduce damage to the ozone layer. When specifically used as a vehicle fuel, it is often referred to as autogas or even just as gas.

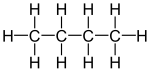

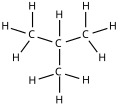

Varieties of LPG that are bought and sold include mixes that are mostly propane (C

3H

8), mostly butane (C

4H

10),

and, most commonly, mixes including both propane and butane. In the

northern hemisphere winter, the mixes contain more propane, while in

summer, they contain more butane. In the United States,

mainly two grades of LPG are sold: commercial propane and HD-5. These

specifications are published by the Gas Processors Association (GPA) and the American Society of Testing and Materials. Propane/butane blends are also listed in these specifications.

Propylene, butylenes and various other hydrocarbons are usually also present in small concentrations such as C2H6, CH4, and C3H8. HD-5 limits the amount of propylene that can be placed in LPG to 5% and is utilized as an autogas specification. A powerful odorant, ethanethiol, is added so that leaks can be detected easily. The internationally recognized European Standard is EN 589. In the United States, tetrahydrothiophene (thiophane) or amyl mercaptan are also approved odorants, although neither is currently being utilized.

LPG is prepared by refining petroleum or "wet" natural gas, and is almost entirely derived from fossil fuel sources, being manufactured during the refining of petroleum (crude oil), or extracted from petroleum or natural gas streams as they emerge from the ground. It was first produced in 1910 by Walter O. Snelling, and the first commercial products appeared in 1912. It currently provides about 3% of all energy consumed, and burns relatively cleanly with no soot and very little sulfur emission. As it is a gas, it does not pose ground or water pollution hazards, but it can cause air pollution. LPG has a typical specific calorific value of 46.1 MJ/kg compared with 42.5 MJ/kg for fuel oil and 43.5 MJ/kg for premium grade petrol (gasoline). However, its energy density per volume unit of 26 MJ/L is lower than either that of petrol or fuel oil, as its relative density is lower (about 0.5–0.58 kg/L, compared to 0.71–0.77 kg/L for gasoline). As the density and vapor pressure of LPG (or its components) change significantly with temperature, this fact must be considered every time when the application is connected with safety or custody transfer operations, e.g. typical cuttoff level option for LPG reservoir is 85%.

Besides its use as an energy carrier, LPG is also a promising feedstock in the chemical industry for the synthesis of olefins such as ethylene, propylene,

As its boiling point is below room temperature, LPG will evaporate quickly at normal temperatures and pressures and is usually supplied in pressurized steel vessels. They are typically filled to 80–85% of their capacity to allow for thermal expansion of the contained liquid. The ratio of the densities of the liquid and vapor varies depending on composition, pressure, and temperature, but is typically around 250:1. The pressure at which LPG becomes liquid, called its vapour pressure, likewise varies depending on composition and temperature; for example, it is approximately 220 kilopascals (32 psi) for pure butane at 20 °C (68 °F), and approximately 2,200 kilopascals (320 psi) for pure propane at 55 °C (131 °F). LPG in its gaseous phase is still heavier than air, unlike natural gas, and thus will flow along floors and tend to settle in low spots, such as basements. There are two main dangers to this. The first is a possible explosion if the mixture of LPG and air is within the explosive limits and there is an ignition source. The second is suffocation due to LPG displacing air, causing a decrease in oxygen concentration.

A full LPG gas cylinder contains 86% liquid; the ullage volume will contain vapour at a pressure that varies with temperature.

Uses

LPG has a wide variety of uses in many different markets as an efficient fuel container in the agricultural, recreation, hospitality, industrial, construction, sailing and fishing sectors. It can serve as fuel for cooking, central heating and water heating and is a particularly cost-effective and efficient way to heat off-grid homes.

Cooking

LPG is used for cooking in many countries for economic reasons, for convenience or because it is the preferred fuel source.

In India, nearly 8.9 million tons of LPG were consumed in the six months between April and September 2016 in the domestic sector, mainly for cooking. The number of domestic connections are 215 million (i.e., one connection for every six people) with a circulation of more than 350 million LPG cylinders. Most of the LPG requirement is imported. Piped city gas supply in India is not yet developed on a major scale. LPG is subsidised by the Indian government for domestic users. An increase in LPG prices has been a politically sensitive matter in India as it potentially affects the middle class voting pattern.

LPG was once a standard cooking fuel in Hong Kong; however, the continued expansion of town gas to newer buildings has reduced LPG usage to less than 24% of residential units. However, other than electric, induction, or infrared stoves, LPG-fueled stoves are the only type available in most suburban villages and many public housing estates.

LPG is the most common cooking fuel in Brazilian urban areas, being used in virtually all households, with the exception of the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, which have a natural gas pipeline infrastructure. Since 2001, poor families receive a government grant ("Vale Gás") used exclusively for the acquisition of LPG. Since 2003, this grant is part of the government's main social welfare program ("Bolsa Família"). Also, since 2005, the national oil company Petrobras differentiates between LPG destined for cooking and LPG destined for other uses, establishing a lower price for the former. This is a result of a directive from the Brazilian federal government, but its discontinuation is currently being debated.

LPG is commonly used in North America for domestic cooking and outdoor grilling.

Rural heating

Predominantly in Europe and rural parts of many countries, LPG can provide an alternative to electric heating, heating oil, or kerosene. LPG is most often used in areas that do not have direct access to piped natural gas. In the UK about 200,000 households use LPG for heating.

LPG can be used as a power source for combined heat and power technologies (CHP). CHP is the process of generating both electrical power and useful heat from a single fuel source. This technology has allowed LPG to be used not just as fuel for heating and cooking, but also for decentralized generation of electricity.

LPG can be stored in a variety of manners. LPG, as with other fossil fuels, can be combined with renewable power sources to provide greater reliability while still achieving some reduction in CO2 emissions. However, as opposed to wind and solar renewable energy sources, LPG can be used as a standalone energy source without the prohibitive expense of electrical energy storage. In many climates renewable sources such as solar and wind power would still require the construction, installation and maintenance of reliable baseload power sources such as LPG fueled generation to provide electrical power during the entire year. 100% wind/solar is possible, the caveat being that the expense of the additional generation capacity necessary to charge batteries plus the cost of battery electrical storage makes this option economically feasible in only a minority of situations.

Motor fuel

When LPG is used to fuel internal combustion engines, it is often referred to as autogas or auto propane. In some countries, it has been used since the 1940s as a petrol alternative for spark ignition engines. In some countries, there are additives in the liquid that extend engine life and the ratio of butane to propane is kept quite precise in fuel LPG. Two recent studies have examined LPG-fuel-oil fuel mixes and found that smoke emissions and fuel consumption are reduced but hydrocarbon emissions are increased. The studies were split on CO emissions, with one finding significant increases, and the other finding slight increases at low engine load but a considerable decrease at high engine load. Its advantage is that it is non-toxic, non-corrosive and free of tetraethyllead or any additives, and has a high octane rating (102–108 RON depending on local specifications). It burns more cleanly than petrol or fuel-oil and is especially free of the particulates present in the latter.

LPG has a lower energy density per liter than either petrol or fuel-oil, so the equivalent fuel consumption is higher. Many governments impose less tax on LPG than on petrol or fuel-oil, which helps offset the greater consumption of LPG than of petrol or fuel-oil. However, in many European countries, this tax break is often compensated by a much higher annual tax on cars using LPG than on cars using petrol or fuel-oil. Propane is the third most widely used motor fuel in the world. 2013 estimates are that over 24.9 million vehicles are fueled by propane gas worldwide. Over 25 million tonnes (over 9 billion US gallons) are used annually as a vehicle fuel.

Not all automobile engines are suitable for use with LPG as a fuel. LPG provides less upper cylinder lubrication than petrol or diesel, so LPG-fueled engines are more prone to valve wear if they are not suitably modified. Many modern common rail diesel engines respond well to LPG use as a supplementary fuel. This is where LPG is used as fuel as well as diesel. Systems are now available that integrate with OEM engine management systems.

Conversion kits can switch a vehicle dedicated to gasoline to using a dual system, in which both gasoline and LPG are used in the same vehicle.

In 2020, BW LPG successfully retrofitted a Very Large Gas Carrier (VLGC) with LPG propulsion technology, pioneering LPG's application in large-scale maritime operations. LPG’s lowers emissions of carbon dioxide, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter align with stricter standards set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), making LPG a viable transition option as the maritime industry transitions towards net zero carbon emissions.

Conversion to gasoline

LPG can be converted into alkylate which is a premium gasoline blending stock because it has exceptional anti-knock properties and gives clean burning.

Refrigeration

LPG is instrumental in providing off-the-grid refrigeration, usually by means of a gas absorption refrigerator.

Blended from pure, dry propane (refrigerant designator R-290) and isobutane (R-600a) the blend "R-290a" has negligible ozone depletion potential, very low global warming potential and can serve as a functional replacement for R-12, R-22, R-134a and other chlorofluorocarbon or hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants in conventional stationary refrigeration and air conditioning systems.

Such substitution is widely prohibited or discouraged in motor vehicle air conditioning systems, on the grounds that using flammable hydrocarbons in systems originally designed to carry non-flammable refrigerant presents a significant risk of fire or explosion.

Vendors and advocates of hydrocarbon refrigerants argue against such bans on the grounds that there have been very few such incidents relative to the number of vehicle air conditioning systems filled with hydrocarbons. One particular test, conducted by a professor at the University of New South Wales, unintentionally tested the worst-case scenario of a sudden and complete refrigerant expulsion into the passenger compartment followed by subsequent ignition. He and several others in the car sustained minor burns to their face, ears, and hands, and several observers received lacerations from the burst glass of the front passenger window. No one was seriously injured.

Propellant

Global production

Global LPG production reached over 292 million metric tons per year (Mt/a) in 2015, while global LPG consumption to over 284 Mt/a. 62% of LPG is extracted from natural gas while the rest is produced by petroleum refineries from crude oil. 44% of global consumption is in the domestic sector. The U.S. is the leading producer and exporter of LPG.

Security of supply

Because of the natural gas and the oil-refining industry, Europe is almost self-sufficient in LPG. Europe's security of supply is further safeguarded by:

- a wide range of sources, both inside and outside Europe;

- a flexible supply chain via water, rail and road with numerous routes and entry points into Europe.

According to 2010–12 estimates, proven world reserves of natural gas, from which most LPG is derived, stand at 300 trillion cubic meters (10,600 trillion cubic feet). Production continues to grow at an average annual rate of 2.2%.

Comparison with natural gas

LPG is composed mainly of propane and butane, while natural gas is composed of the lighter methane and ethane. LPG, vaporised and at atmospheric pressure, has a higher calorific value (46 MJ/m3 equivalent to 12.8 kWh/m3) than natural gas (methane) (38 MJ/m3 equivalent to 10.6 kWh/m3), which means that LPG cannot simply be substituted for natural gas. In order to allow the use of the same burner controls and to provide for similar combustion characteristics, LPG can be mixed with air to produce a synthetic natural gas (SNG) that can be easily substituted. LPG/air mixing ratios average 60/40, though this is widely variable based on the gases making up the LPG. The method for determining the mixing ratios is by calculating the Wobbe index of the mix. Gases having the same Wobbe index are held to be interchangeable.

LPG-based SNG is used in emergency backup systems for many public, industrial and military installations, and many utilities use LPG peak shaving plants in times of high demand to make up shortages in natural gas supplied to their distributions systems. LPG-SNG installations are also used during initial gas system introductions when the distribution infrastructure is in place before gas supplies can be connected. Developing markets in India and China (among others) use LPG-SNG systems to build up customer bases prior to expanding existing natural gas systems.

LPG-based SNG or natural gas with localized storage and piping distribution network to the households for catering to each cluster of 5000 domestic consumers can be planned under the initial phase of the city gas network system. This would eliminate the last mile LPG cylinders road transport which is a cause of traffic and safety hurdles in Indian cities. These localized natural gas networks are successfully operating in Japan with feasibility to get connected to wider networks in both villages and cities.

Environmental effects

Commercially available LPG is currently derived mainly from fossil fuels. Burning LPG releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. The reaction also produces some carbon monoxide. LPG does, however, release less CO

2 per unit of energy than does coal or oil, but more than natural gas. It emits 81% of the CO

2 per kWh produced by oil, 70% of that of coal, and less than 50% of that emitted by coal-generated electricity distributed via the grid. Being a mix of propane and butane, LPG emits less carbon per joule than butane but more carbon per joule than propane.

LPG burns more cleanly than higher molecular weight hydrocarbons because it releases less particulate matter.

As it is much less polluting than most traditional solid-fuel stoves, replacing cookstoves used in developing countries with LPG is one of the key strategies adopted to reduce household air pollution in the developing world.

Fire/explosion risk and mitigation

In a refinery or gas plant, LPG must be stored in pressure vessels. These containers are either cylindrical and horizontal (sometimes referred to as bullet tanks) or spherical (of the Horton sphere type). Typically, these vessels are designed and manufactured according to some code. In the United States, this code is governed by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).

LPG containers have pressure relief valves, such that when subjected to exterior heating sources, they will vent LPGs to the atmosphere or a flare stack.

If a tank is subjected to a fire of sufficient duration and intensity, it can undergo a boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE). This is typically a concern for large refineries and petrochemical plants that maintain very large containers. In general, tanks are designed so that the product will vent faster than pressure can build to dangerous levels.

One remedy that is utilized in industrial settings is to equip such containers with a measure to provide a fire-resistance rating. Large, spherical LPG containers may have up to a 15 cm steel wall thickness. They are equipped with an approved pressure relief valve. A large fire in the vicinity of the vessel will increase its temperature and pressure. The relief valve on the top is designed to vent off excess pressure in order to prevent the rupture of the container itself. Given a fire of sufficient duration and intensity, the pressure being generated by the boiling and expanding gas can exceed the ability of the valve to vent the excess. Alternatively, if, due to continued venting, the liquid level drops below the area being heated, the tank structure can be overheated and subsequently weakened in that area. If either occurs, the container may rupture violently, launching pieces of the vessel at high velocity, while the released products can ignite as well, potentially causing catastrophic damage to anything nearby, including other containers.

People can be exposed to LPG in the workplace by breathing it in, skin contact, and eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (Permissible exposure limit) for LPG exposure in the workplace as 1000 ppm (1800 mg/m3) over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 1000 ppm (1800 mg/m3) over an 8-hour workday. At levels of 2000 ppm, 10% of the lower explosive limit, LPG is considered immediately dangerous to life and health (due solely to safety considerations pertaining to risk of explosion).