| Sleep paralysis | |

|---|---|

| |

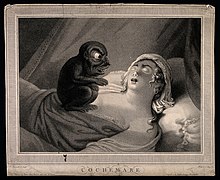

| The Nightmare by Swiss artist Henry Fuseli (1781) is thought to be a depiction of sleep paralysis perceived as a demonic visitation. | |

| Specialty | |

| Symptoms |

|

| Complications | Nyctophobia |

| Duration | No more than a couple of minutes |

| Risk factors | |

| Diagnostic method | Based on description |

| Differential diagnosis | |

| Treatment | |

| Frequency | 8–50% |

| Deaths | None; harmless |

Sleep paralysis is a state, during waking up or falling asleep, in which a person is conscious but in a complete state of full-body paralysis. During an episode, the person may hallucinate (hear, feel, or see things that are not there), which often results in fear. Episodes generally last no more than a few minutes. It can recur multiple times or occur as a single episode.

The condition may occur in those who are otherwise healthy or those with narcolepsy, or it may run in families as a result of specific genetic changes. The condition can be triggered by sleep deprivation, psychological stress, or abnormal sleep cycles. The underlying mechanism is believed to involve a dysfunction in REM sleep. Diagnosis is based on a person's description. Other conditions that can present similarly include narcolepsy, atonic seizure, and hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Treatment options for sleep paralysis have been poorly studied. It is recommended that people be reassured that the condition is common and generally not serious. Other efforts that may be tried include sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioral therapy, and antidepressants.

Between 8% and 50% of people experience sleep paralysis at some point during their life. About 5% of people have regular episodes. Males and females are affected equally. Sleep paralysis has been described throughout history. It is believed to have played a role in the creation of stories about alien abduction and other paranormal events.

Symptoms and signs

The main symptom of sleep paralysis is being unable to move or speak during awakening.

Imagined sounds such as humming, hissing, static, zapping and buzzing noises are reported during sleep paralysis. Other sounds such as voices, whispers and roars are also experienced. It has also been known that one may feel pressure on their chest and intense pain in their head during an episode. These symptoms are usually accompanied by intense emotions such as fear and panic. People also have sensations of being dragged out of bed or of flying, numbness, and feelings of electric tingles or vibrations running through their body.

Sleep paralysis may include hallucinations, such as an intruding presence or dark figure in the room. These are commonly known as sleep paralysis demons. It may also include suffocating or the individual feeling a sense of terror, accompanied by a feeling of pressure on one's chest and difficulty breathing.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of sleep paralysis has not been concretely identified, although there are several theories about its cause. The first of these stems from the understanding that sleep paralysis is a parasomnia resulting from dysfunctional overlap of the REM and waking stages of sleep. Polysomnographic studies found that individuals who experience sleep paralysis have shorter REM sleep latencies than normal along with shortened NREM and REM sleep cycles, and fragmentation of REM sleep. This study supports the observation that disturbance of regular sleeping patterns can precipitate an episode of sleep paralysis, because fragmentation of REM sleep commonly occurs when sleep patterns are disrupted and has now been seen in combination with sleep paralysis.

Another major theory is that the neural functions that regulate sleep are out of balance in such a way that causes different sleep states to overlap. In this case, cholinergic sleep "on" neural populations are hyperactivated and the serotonergic sleep "off" neural populations are under-activated. As a result, the cells capable of sending the signals that would allow for complete arousal from the sleep state, the serotonergic neural populations, have difficulty in overcoming the signals sent by the cells that keep the brain in the sleep state. During normal REM sleep, the threshold for a stimulus to cause arousal is greatly elevated. Under normal conditions, medial and vestibular nuclei, cortical, thalamic, and cerebellar centers coordinate things such as head and eye movement, and orientation in space.

In individuals reporting sleep paralysis, there is almost no blocking of exogenous stimuli, which means it is much easier for a stimulus to arouse the individual. The vestibular nuclei in particular has been identified as being closely related to dreaming during the REM stage of sleep. According to this hypothesis, vestibular-motor disorientation, unlike hallucinations, arise from completely endogenous sources of stimuli.

If the effects of sleep "on" neural populations cannot be counteracted, characteristics of REM sleep are retained upon awakening. Common consequences of sleep paralysis include headaches, muscle pains or weakness or paranoia. As the correlation with REM sleep suggests, the paralysis is not complete: use of EOG traces shows that eye movement is still possible during such episodes; however, the individual experiencing sleep paralysis is unable to speak.

Research has found a genetic component in sleep paralysis. The characteristic fragmentation of REM sleep, hypnopompic, and hypnagogic hallucinations have a heritable component in other parasomnias, which lends credence to the idea that sleep paralysis is also genetic. Twin studies have shown that if one twin of a monozygotic pair (identical twins) experiences sleep paralysis that other twin is very likely to experience it as well. The identification of a genetic component means that there is some sort of disruption of a function at the physiological level. Further studies must be conducted to determine whether there is a mistake in the signaling pathway for arousal as suggested by the first theory presented, or whether the regulation of melatonin or the neural populations themselves have been disrupted.

Hallucinations

Several types of hallucinations have been linked to sleep paralysis: the belief that there is an intruder in the room, the feeling of a presence, and the sensation of floating. One common hallucination is the presence of an Incubus. A neurological hypothesis is that in sleep paralysis the cerebellum, which usually coordinates body movement and provides information on body position, experiences a brief myoclonic spike in brain activity inducing a floating sensation.

The intruder and incubus hallucinations highly correlate with one another, and moderately correlated with the third hallucination, vestibular-motor disorientation, also known as out-of-body experiences, which differ from the other two in not involving the threat-activated vigilance system.

Threat hyper-vigilance

A hyper-vigilant state created in the midbrain may further contribute to hallucinations. More specifically, the emergency response is activated in the brain when individuals wake up paralyzed and feel vulnerable to attack. This helplessness can intensify the effects of the threat response well above the level typical of normal dreams, which could explain why such visions during sleep paralysis are so vivid. The threat-activated vigilance system is a protective mechanism that differentiates between dangerous situations and determines whether the fear response is appropriate.

The hyper-vigilance response can lead to the creation of endogenous stimuli that contribute to the perceived threat. A similar process may explain hallucinations, with slight variations, in which an evil presence is perceived by the subject to be attempting to suffocate them, either by pressing heavily on the chest or by strangulation. A neurological explanation holds that this results from a combination of the threat vigilance activation system and the muscle paralysis associated with sleep paralysis that removes voluntary control of breathing. Several features of REM breathing patterns exacerbate the feeling of suffocation. These include shallow rapid breathing, hypercapnia, and slight blockage of the airway, which is a symptom prevalent in sleep apnea patients.

According to this account, the subjects attempt to breathe deeply and find themselves unable to do so, creating a sensation of resistance, which the threat-activated vigilance system interprets as an unearthly being sitting on their chest, threatening suffocation. The sensation of entrapment causes a feedback loop when the fear of suffocation increases as a result of continued helplessness, causing the subjects to struggle to end the SP episode.

Diagnosis

Sleep paralysis is mainly diagnosed via clinical interview and ruling out other potential sleep disorders that could account for the feelings of paralysis. Several measures are available to reliably diagnose or screen (Munich Parasomnia Screening) for recurrent isolated sleep paralysis.

Diagnosis

Episodes of sleep paralysis can occur in the context of several medical conditions (e.g., narcolepsy, hypokalemia). When episodes occur independent of these conditions or substance use, it is termed "isolated sleep paralysis" (ISP). When ISP episodes are more frequent and cause clinically significant distress or interference, it is classified as "recurrent isolated sleep paralysis" (RISP). Episodes of sleep paralysis, regardless of classification, are generally short (1–6 minutes), but longer episodes have been documented.

It can be difficult to differentiate between cataplexy brought on by narcolepsy and true sleep paralysis, because the two phenomena are physically indistinguishable. The best way to differentiate between the two is to note when the attacks occur most often. Narcolepsy attacks are more common when the individual is falling asleep; ISP and RISP attacks are more common upon awakening.

Differential diagnosis

Similar conditions include:

- Exploding head syndrome (EHS) potentially frightening parasomnia, the hallucinations are usually briefer always loud or jarring and there is no paralysis during EHS.

- Nightmare disorder (ND); also REM-based parasomnia

- Sleep terrors (STs) potentially frightening parasomnia but are not REM based and there is a lack of awareness to surroundings, characteristic screams during STs.

- Noctural panic attacks (NPAs) involves fear and acute distress but lacks paralysis and dream imagery

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often includes scary imagery and anxiety but not limited to sleep-wake transitions

Prevention

Several circumstances have been identified that are associated with an increased risk of sleep paralysis. These include insomnia, sleep deprivation, an erratic sleep schedule, stress, and physical fatigue. It is also believed that there may be a genetic component in the development of RISP, because there is a high concurrent incidence of sleep paralysis in monozygotic twins. Sleeping in the supine position has been found an especially prominent instigator of sleep paralysis.

Sleeping in the supine position is believed to make the sleeper more vulnerable to episodes of sleep paralysis because in this sleeping position it is possible for the soft palate to collapse and obstruct the airway. This is a possibility regardless of whether the individual has been diagnosed with sleep apnea or not. There may also be a greater rate of microarousals while sleeping in the supine position because there is a greater amount of pressure being exerted on the lungs by gravity.

While many factors can increase the risk for ISP or RISP, they can be avoided with minor lifestyle changes.

Treatment

Medical treatment starts with education about sleep stages and the inability to move muscles during REM sleep. People should be evaluated for narcolepsy if symptoms persist. The safest treatment for sleep paralysis is for people to adopt healthier sleeping habits. However, in more serious cases tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be used. Despite the fact that these treatments are prescribed there is currently no drug that has been found to completely interrupt episodes of sleep paralysis a majority of the time.

Medications

Though no large trials have taken place which focus on the treatment of sleep paralysis, several drugs have promise in case studies. Two trials of GHB for people with narcolepsy demonstrated reductions in sleep paralysis episodes.

Pimavanserin has been proposed as a possible candidate for future studies in treating sleep paralysis.

Cognitive-behavior therapy

Some of the earliest work in treating sleep paralysis was done using a cognitive-behavior therapy called CA-CBT. The work focuses on psycho-education and modifying catastrophic cognitions about the sleep paralysis attack. This approach has previously been used to treat sleep paralysis in Egypt, although clinical trials are lacking.

The first published psychosocial treatment for recurrent isolated sleep paralysis was cognitive-behavior therapy for isolated sleep paralysis (CBT-ISP). It begins with self-monitoring of symptoms, cognitive restructuring of maladaptive thoughts relevant to ISP (e.g., "the paralysis will be permanent"), and psychoeducation about the nature of sleep paralysis. Prevention techniques include ISP-specific sleep hygiene and the preparatory use of various relaxation techniques (e.g. diaphragmatic breathing, mindfulness, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation). Episode disruption techniques are first practiced in session and then applied during actual attacks. No controlled trial of CBT-ISP has yet been conducted to prove its effectiveness.

Epidemiology

Sleep paralysis is experienced equally in males and females. Lifetime prevalence rates derived from 35 aggregated studies indicate that approximately 8% of the general population, 28% of students, and 32% of psychiatric patients experience at least one episode of sleep paralysis at some point in their lives. Rates of recurrent sleep paralysis are not as well known, but 15–45% of those with a lifetime history of sleep paralysis may meet diagnostic criteria for Recurrent Isolated Sleep Paralysis. In surveys from Canada, China, England, Japan and Nigeria, 20% to 60% of individuals reported having experienced sleep paralysis at least once in their lifetime. In general, non-whites appear to experience sleep paralysis at higher rates than whites, but the magnitude of the difference is rather small. Approximately 36% of the general population that experiences isolated sleep paralysis develop it between 25 and 44 years of age.

Isolated sleep paralysis is commonly seen in patients that have been diagnosed with narcolepsy. Approximately 30–50% of people that have been diagnosed with narcolepsy have experienced sleep paralysis as an auxiliary symptom. A majority of the individuals who have experienced sleep paralysis have sporadic episodes that occur once a month to once a year. Only 3% of individuals experiencing sleep paralysis that is not associated with a neuromuscular disorder have nightly episodes.

Society and culture

Etymology

The original definition of sleep paralysis was codified by Samuel Johnson in his A Dictionary of the English Language as nightmare, a term that evolved into the modern definition. The term was first used and dubbed by British neurologist, S.A.K. Wilson in his 1928 dissertation, The Narcolepsies. Such sleep paralysis was widely considered the work of demons, and more specifically incubi, which were thought to sit on the chests of sleepers. In Old English the name for these beings was mare or mære (from a proto-Germanic *marōn, cf. Old Norse mara), hence comes the mare in the word nightmare. The word might be cognate to Greek Marōn (in the Odyssey) and Sanskrit Māra.

Cultural significance and priming

Although the core features of sleep paralysis (e.g., atonia, a clear sensorium, and frequent hallucinations) appear to be universal, the ways in which they are experienced vary according to time, place, and culture. Over 100 terms have been identified for these experiences. Some scientists have proposed sleep paralysis as an explanation for reports of paranormal and spiritual phenomena such as ghosts, alien visits, demons or demonic possession, alien abduction experiences, the night hag and shadow people haunting.

According to some scientists, culture may be a major factor in shaping sleep paralysis. When sleep paralysis is interpreted through a particular cultural filter, it may take on greater salience. For example, if sleep paralysis is feared in a certain culture, this fear could lead to conditioned fear, and thus worsen the experience, in turn leading to higher rates. Consistent with this idea, high rates and long durations of immobility during sleep paralysis have been found in Egypt, where there are elaborate beliefs about sleep paralysis, involving malevolent spirit-like creatures, the jinn.

Research has found that sleep paralysis is associated with great fear and fear of impending death in 50% of sufferers in Egypt. A study comparing rates and characteristics of sleep paralysis in Egypt and Denmark found that the phenomenon is three times more common in Egypt than Denmark. In Denmark, unlike Egypt, there are no elaborate supernatural beliefs about sleep paralysis, and the experience is often interpreted as an odd physiological event, with overall shorter sleep paralysis episodes and fewer people (17%) fearing that they could die from it.

Folklore

The night hag is a generic name for a folkloric creature found in cultures around the world, and which is used to explain the phenomenon of sleep paralysis. A common description is that a person feels a presence of a supernatural malevolent being which immobilizes the person as if standing on the chest. This phenomenon goes by many names.

Albania

In Albanian folk beliefs, Mokthi is believed to be a male spirit with a golden fez hat who appears to women who are usually tired or suffering and stops them from moving. It is believed that if they can take his golden hat, he will grant them a wish, but then he will visit them frequently although he is harmless. There are talismans that can provide protection from Mokthi and one way is to put one's husband's hat near the pillow while sleeping. Mokthi or Makthi in Albanian means "Nightmare".

Bengal

In Bengali folklore, sleep paralysis is believed to be caused by a supernatural entity called Boba (Bengali: বোবা, lit. 'dumb'). Boba attacks a person by strangling him when the person sleeps in a supine position. In Bengal, the phenomenon is called Bobay Dhora (Bengali: বোবায় ধরা, lit. 'Struck by Boba').

Cambodia

Sleep paralysis among Cambodians is known as "the ghost pushes you down," and entails the belief in dangerous visitations from deceased relatives.

Egypt

In Egypt, sleep paralysis is conceptualized as a terrifying jinn attack.

Italy

In the different regions of Italy there are many examples of supernatural beings associated with sleep paralysis. In the regions of Marche and Abruzzo, it is referred to as a Pandafeche or pantafica attack; the Pandafeche usually refers to an evil witch, sometimes a ghostlike spirit or a terrifying catlike creature, that mounts on the chest of the victim and tries to harm him. The only way to avoid her is to keep a bag of sand or beans close to the bed, so that the witch will stop to count how many beans or sand-grains are inside it. A similar tradition is present in the Sardinian folklore, where the Ammuntadore is known as a creature that mounts on the people's chest during their sleep to give them nightmares, and that can change its shape according to the person's fears. In Northern Italy, specifically in the Tyrol area, the Trud is a witch that sits on the people's chest at night, making them unable to breathe; to chase her away, people should make the sign of the Cross, something that would need a great struggle in a situation of paralysis. A similar folklore is present in the Sannio area, around the city of Benevento, where the witch is called Janara. In Southern Italy, sleep paralysis is usually explained with the presence of a sprite standing on the people's chest: if the person manages to catch the sprite (or steal his hat), in exchange for his freedom (or to have his hat back) he can reveal the hiding place of a rich treasure; this sprite has different names in different regions of Italy: Monaciello in Campania, Monachicchio in Basilicata, Laurieddhu or Scazzamurill in Apulia, Mazzmuredd in Molise.

Newfoundland

In Newfoundland, sleep paralysis is referred to as the Old Hag, and victims of a hagging are said to be hag-ridden upon awakening. Victims report being completely conscious, but unable to speak or move, and report a person or an animal which sits upon their chest. Despite the name, the attacker can be either male or female. Some suggested cures or preventions for the Old Hag include sleeping with a Bible under the pillow, calling the sleeper's name backwards or in an extreme example, sleeping with a shingle or board embedded with nails strapped to the chest. This object was called a Hag Board. The Old Hag is well-enough known in the province to be a pop culture figure, appearing in films and plays as well as in crafted objects.

Nigeria

Nigeria has myriad interpretations of the cause of sleep paralysis, due to numerous cultures and belief systems that exist there.

United States

Sleep paralysis is sometimes interpreted as space alien abduction in the United States.

Literature

Various forms of magic and spiritual possession were also advanced as causes in literature. In nineteenth century Europe, the vagaries of diet were thought to be responsible. For example, in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Ebenezer Scrooge attributes the ghost he sees to "... an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato..." In a similar vein, the Household Cyclopedia (1881) offers the following advice about nightmares:

Great attention is to be paid to regularity and choice of diet. Intemperance of every kind is hurtful, but nothing is more productive of this disease than drinking bad wine. Of eatables those which are most prejudicial are all fat and greasy meats and pastry... Moderate exercise contributes in a superior degree to promote the digestion of food and prevent flatulence; those, however, who are necessarily confined to a sedentary occupation, should particularly avoid applying themselves to study or bodily labor immediately after eating... Going to bed before the usual hour is a frequent cause of night-mare, as it either occasions the patient to sleep too long or to lie long awake in the night. Passing a whole night or part of a night without rest likewise gives birth to the disease, as it occasions the patient, on the succeeding night, to sleep too soundly. Indulging in sleep too late in the morning, is an almost certain method to bring on the paroxysm, and the more frequently it returns, the greater strength it acquires; the propensity to sleep at this time is almost irresistible.

J. M. Barrie, the author of the Peter Pan stories, may have had sleep paralysis. He said of himself "In my early boyhood it was a sheet that tried to choke me in the night." He also described several incidents in the Peter Pan stories that indicate that he was familiar with an awareness of a loss of muscle tone whilst in a dream-like state. For example, Maimie is asleep but calls out "What was that....It is coming nearer! It is feeling your bed with its horns-it is boring for [into] you", and when the Darling children were dreaming of flying, Barrie says "Nothing horrid was visible in the air, yet their progress had become slow and laboured, exactly as if they were pushing their way through hostile forces. Sometimes they hung in the air until Peter had beaten on it with his fists." Barrie describes many parasomnias and neurological symptoms in his books and uses them to explore the nature of consciousness from an experiential point of view.