The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest written records of identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia from around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India. Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400 to 1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance.

The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived "natural philosophy", which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape, along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".

New knowledge in science is advanced by research from scientists who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems. Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic and research institutions, government agencies, and companies. The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritising the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments, health care, public infrastructure, and environmental protection.

Etymology

The word science has been used in Middle English since the 14th century in the sense of "the state of knowing". The word was borrowed from the Anglo-Norman language as the suffix -cience, which was borrowed from the Latin word scientia, meaning "knowledge, awareness, understanding". It is a noun derivative of the Latin sciens meaning "knowing", and undisputedly derived from the Latin sciō, the present participle scīre, meaning "to know".

There are many hypotheses for science's ultimate word origin. According to Michiel de Vaan, Dutch linguist and Indo-Europeanist, sciō may have its origin in the Proto-Italic language as *skije- or *skijo- meaning "to know", which may originate from Proto-Indo-European language as *skh1-ie, *skh1-io, meaning "to incise". The Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben proposed sciō is a back-formation of nescīre, meaning "to not know, be unfamiliar with", which may derive from Proto-Indo-European *sekH- in Latin secāre, or *skh2-, from *sḱʰeh2(i)- meaning "to cut".

In the past, science was a synonym for "knowledge" or "study", in keeping with its Latin origin. A person who conducted scientific research was called a "natural philosopher" or "man of science". In 1834, William Whewell introduced the term scientist in a review of Mary Somerville's book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, crediting it to "some ingenious gentleman" (possibly himself).

History

Early history

Science has no single origin. Rather, systematic methods emerged gradually over the course of tens of thousands of years, taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Women likely played a central role in prehistoric science, as did religious rituals. Some scholars use the term "protoscience" to label activities in the past that resemble modern science in some but not all features; however, this label has also been criticised as denigrating, or too suggestive of presentism, thinking about those activities only in relation to modern categories.

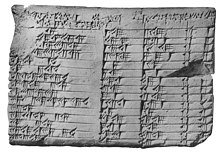

Direct evidence for scientific processes becomes clearer with the advent of writing systems in early civilisations like Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, creating the earliest written records in the history of science in around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Although the words and concepts of "science" and "nature" were not part of the conceptual landscape at the time, the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians made contributions that would later find a place in Greek and medieval science: mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. From the 3rd millennium BCE, the ancient Egyptians developed a decimal numbering system, solved practical problems using geometry, and developed a calendar. Their healing therapies involved drug treatments and the supernatural, such as prayers, incantations, and rituals.

The ancient Mesopotamians used knowledge about the properties of various natural chemicals for manufacturing pottery, faience, glass, soap, metals, lime plaster, and waterproofing. They studied animal physiology, anatomy, behaviour, and astrology for divinatory purposes. The Mesopotamians had an intense interest in medicine and the earliest medical prescriptions appeared in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur. They seem to have studied scientific subjects which had practical or religious applications and had little interest in satisfying curiosity.

Classical antiquity

In classical antiquity, there is no real ancient analogue of a modern scientist. Instead, well-educated, usually upper-class, and almost universally male individuals performed various investigations into nature whenever they could afford the time. Before the invention or discovery of the concept of phusis or nature by the pre-Socratic philosophers, the same words tend to be used to describe the natural "way" in which a plant grows, and the "way" in which, for example, one tribe worships a particular god. For this reason, it is claimed that these men were the first philosophers in the strict sense and the first to clearly distinguish "nature" and "convention".

The early Greek philosophers of the Milesian school, which was founded by Thales of Miletus and later continued by his successors Anaximander and Anaximenes, were the first to attempt to explain natural phenomena without relying on the supernatural. The Pythagoreans developed a complex number philosophy and contributed significantly to the development of mathematical science. The theory of atoms was developed by the Greek philosopher Leucippus and his student Democritus. Later, Epicurus would develop a full natural cosmology based on atomism, and would adopt a "canon" (ruler, standard) which established physical criteria or standards of scientific truth. The Greek doctor Hippocrates established the tradition of systematic medical science and is known as "The Father of Medicine".

A turning point in the history of early philosophical science was Socrates' example of applying philosophy to the study of human matters, including human nature, the nature of political communities, and human knowledge itself. The Socratic method as documented by Plato's dialogues is a dialectic method of hypothesis elimination: better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. The Socratic method searches for general commonly-held truths that shape beliefs and scrutinises them for consistency. Socrates criticised the older type of study of physics as too purely speculative and lacking in self-criticism.

Aristotle in the 4th century BCE created a systematic program of teleological philosophy. In the 3rd century BCE, Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos was the first to propose a heliocentric model of the universe, with the Sun at the centre and all the planets orbiting it. Aristarchus's model was widely rejected because it was believed to violate the laws of physics, while Ptolemy's Almagest, which contains a geocentric description of the Solar System, was accepted through the early Renaissance instead. The inventor and mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse made major contributions to the beginnings of calculus. Pliny the Elder was a Roman writer and polymath, who wrote the seminal encyclopaedia Natural History.

Positional notation for representing numbers likely emerged between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE along Indian trade routes. This numeral system made efficient arithmetic operations more accessible and would eventually become standard for mathematics worldwide.

Middle Ages

Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the 5th century saw an intellectual decline and knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Western Europe. During the period, Latin encyclopaedists such as Isidore of Seville preserved the majority of general ancient knowledge. In contrast, because the Byzantine Empire resisted attacks from invaders, they were able to preserve and improve prior learning. John Philoponus, a Byzantine scholar in the 500s, started to question Aristotle's teaching of physics, introducing the theory of impetus. His criticism served as an inspiration to medieval scholars and Galileo Galilei, who extensively cited his works ten centuries later.

During late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, natural phenomena were mainly examined via the Aristotelian approach. The approach includes Aristotle's four causes: material, formal, moving, and final cause. Many Greek classical texts were preserved by the Byzantine empire and Arabic translations were done by groups such as the Nestorians and the Monophysites. Under the Caliphate, these Arabic translations were later improved and developed by Arabic scientists. By the 6th and 7th centuries, the neighbouring Sassanid Empire established the medical Academy of Gondeshapur, which is considered by Greek, Syriac, and Persian physicians as the most important medical center of the ancient world.

The House of Wisdom was established in Abbasid-era Baghdad, Iraq, where the Islamic study of Aristotelianism flourished until the Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Ibn al-Haytham, better known as Alhazen, used controlled experiments in his optical study. Avicenna's compilation of the Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopaedia, is considered to be one of the most important publications in medicine and was used until the 18th century.

By the eleventh century most of Europe had become Christian, and in 1088, the University of Bologna emerged as the first university in Europe. As such, demand for Latin translation of ancient and scientific texts grew, a major contributor to the Renaissance of the 12th century. Renaissance scholasticism in western Europe flourished, with experiments done by observing, describing, and classifying subjects in nature. In the 13th century, medical teachers and students at Bologna began opening human bodies, leading to the first anatomy textbook based on human dissection by Mondino de Luzzi.

Renaissance

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the Renaissance, both by challenging long-held metaphysical ideas on perception, as well as by contributing to the improvement and development of technology such as the camera obscura and the telescope. At the start of the Renaissance, Roger Bacon, Vitello, and John Peckham each built up a scholastic ontology upon a causal chain beginning with sensation, perception, and finally apperception of the individual and universal forms of Aristotle. A model of vision later known as perspectivism was exploited and studied by the artists of the Renaissance. This theory uses only three of Aristotle's four causes: formal, material, and final.

In the sixteenth century Nicolaus Copernicus formulated a heliocentric model of the Solar System, stating that the planets revolve around the Sun, instead of the geocentric model where the planets and the Sun revolve around the Earth. This was based on a theorem that the orbital periods of the planets are longer as their orbs are farther from the centre of motion, which he found not to agree with Ptolemy's model.

Johannes Kepler and others challenged the notion that the only function of the eye is perception, and shifted the main focus in optics from the eye to the propagation of light. Kepler is best known, however, for improving Copernicus' heliocentric model through the discovery of Kepler's laws of planetary motion. Kepler did not reject Aristotelian metaphysics and described his work as a search for the Harmony of the Spheres. Galileo had made significant contributions to astronomy, physics and engineering. However, he became persecuted after Pope Urban VIII sentenced him for writing about the heliocentric model.

The printing press was widely used to publish scholarly arguments, including some that disagreed widely with contemporary ideas of nature. Francis Bacon and René Descartes published philosophical arguments in favour of a new type of non-Aristotelian science. Bacon emphasised the importance of experiment over contemplation, questioned the Aristotelian concepts of formal and final cause, promoted the idea that science should study the laws of nature and the improvement of all human life. Descartes emphasised individual thought and argued that mathematics rather than geometry should be used to study nature.

Age of Enlightenment

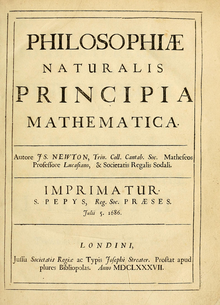

At the start of the Age of Enlightenment, Isaac Newton formed the foundation of classical mechanics by his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, greatly influencing future physicists. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz incorporated terms from Aristotelian physics, now used in a new non-teleological way. This implied a shift in the view of objects: objects were now considered as having no innate goals. Leibniz assumed that different types of things all work according to the same general laws of nature, with no special formal or final causes.

During this time the declared purpose and value of science became producing wealth and inventions that would improve human lives, in the materialistic sense of having more food, clothing, and other things. In Bacon's words, "the real and legitimate goal of sciences is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches", and he discouraged scientists from pursuing intangible philosophical or spiritual ideas, which he believed contributed little to human happiness beyond "the fume of subtle, sublime or pleasing [speculation]".

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were the backbones of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularisation of science among an increasingly literate population. Enlightenment philosophers turned to a few of their scientific predecessors – Galileo, Kepler, Boyle, and Newton principally – as the guides to every physical and social field of the day.

The 18th century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine and physics; the development of biological taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus; a new understanding of magnetism and electricity; and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline. Ideas on human nature, society, and economics evolved during the Enlightenment. Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed A Treatise of Human Nature, which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity. Modern sociology largely originated from this movement. In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, which is often considered the first work on modern economics.

19th century

During the nineteenth century many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape. These included the transformation of the life and physical sciences; the frequent use of precision instruments; the emergence of terms such as "biologist", "physicist", and "scientist"; an increased professionalisation of those studying nature; scientists gaining cultural authority over many dimensions of society; the industrialisation of numerous countries; the thriving of popular science writings; and the emergence of science journals. During the late 19th century, psychology emerged as a separate discipline from philosophy when Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory for psychological research in 1879.

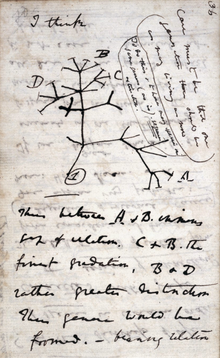

During the mid-19th century Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1858, which explained how different plants and animals originated and evolved. Their theory was set out in detail in Darwin's book On the Origin of Species, published in 1859. Separately, Gregor Mendel presented his paper, "Experiments on Plant Hybridization" in 1865, which outlined the principles of biological inheritance, serving as the basis for modern genetics.

Early in the 19th century John Dalton suggested the modern atomic theory, based on Democritus's original idea of indivisible particles called atoms. The laws of conservation of energy, conservation of momentum and conservation of mass suggested a highly stable universe where there could be little loss of resources. However, with the advent of the steam engine and the Industrial Revolution there was an increased understanding that not all forms of energy have the same energy qualities, the ease of conversion to useful work or to another form of energy. This realisation led to the development of the laws of thermodynamics, in which the free energy of the universe is seen as constantly declining: the entropy of a closed universe increases over time.

The electromagnetic theory was established in the 19th century by the works of Hans Christian Ørsted, André-Marie Ampère, Michael Faraday, James Clerk Maxwell, Oliver Heaviside, and Heinrich Hertz. The new theory raised questions that could not easily be answered using Newton's framework. The discovery of X-rays inspired the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel and Marie Curie in 1896, Marie Curie then became the first person to win two Nobel Prizes. In the next year came the discovery of the first subatomic particle, the electron.

20th century

In the first half of the century the development of antibiotics and artificial fertilisers improved human living standards globally. Harmful environmental issues such as ozone depletion, ocean acidification, eutrophication, and climate change came to the public's attention and caused the onset of environmental studies.

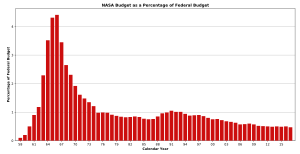

During this period scientific experimentation became increasingly larger in scale and funding. The extensive technological innovation stimulated by World War I, World War II, and the Cold War led to competitions between global powers, such as the Space Race and nuclear arms race. Substantial international collaborations were also made, despite armed conflicts.

In the late 20th century active recruitment of women and elimination of sex discrimination greatly increased the number of women scientists, but large gender disparities remained in some fields. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964 led to a rejection of the steady-state model of the universe in favour of the Big Bang theory of Georges Lemaître.

The century saw fundamental changes within science disciplines. Evolution became a unified theory in the early 20th-century when the modern synthesis reconciled Darwinian evolution with classical genetics. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity and the development of quantum mechanics complement classical mechanics to describe physics in extreme length, time and gravity. Widespread use of integrated circuits in the last quarter of the 20th century combined with communications satellites led to a revolution in information technology and the rise of the global internet and mobile computing, including smartphones. The need for mass systematisation of long, intertwined causal chains and large amounts of data led to the rise of the fields of systems theory and computer-assisted scientific modelling.

21st century

The Human Genome Project was completed in 2003 by identifying and mapping all of the genes of the human genome. The first induced pluripotent human stem cells were made in 2006, allowing adult cells to be transformed into stem cells and turn into any cell type found in the body. With the affirmation of the Higgs boson discovery in 2013, the last particle predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics was found. In 2015, gravitational waves, predicted by general relativity a century before, were first observed. In 2019, the international collaboration Event Horizon Telescope presented the first direct image of a black hole's accretion disc.

Branches

Modern science is commonly divided into three major branches: natural science, social science, and formal science. Each of these branches comprises various specialised yet overlapping scientific disciplines that often possess their own nomenclature and expertise. Both natural and social sciences are empirical sciences, as their knowledge is based on empirical observations and is capable of being tested for its validity by other researchers working under the same conditions.

Natural science

Natural science is the study of the physical world. It can be divided into two main branches: life science and physical science. These two branches may be further divided into more specialised disciplines. For example, physical science can be subdivided into physics, chemistry, astronomy, and earth science. Modern natural science is the successor to the natural philosophy that began in Ancient Greece. Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, and Newton debated the benefits of using approaches that were more mathematical and more experimental in a methodical way. Still, philosophical perspectives, conjectures, and presuppositions, often overlooked, remain necessary in natural science. Systematic data collection, including discovery science, succeeded natural history, which emerged in the 16th century by describing and classifying plants, animals, minerals, and other biotic beings. Today, "natural history" suggests observational descriptions aimed at popular audiences.

Social science

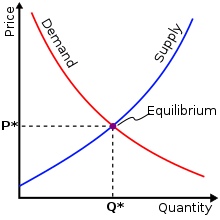

Social science is the study of human behaviour and the functioning of societies. It has many disciplines that include, but are not limited to anthropology, economics, history, human geography, political science, psychology, and sociology. In the social sciences, there are many competing theoretical perspectives, many of which are extended through competing research programs such as the functionalists, conflict theorists, and interactionists in sociology. Due to the limitations of conducting controlled experiments involving large groups of individuals or complex situations, social scientists may adopt other research methods such as the historical method, case studies, and cross-cultural studies. Moreover, if quantitative information is available, social scientists may rely on statistical approaches to better understand social relationships and processes.

Formal science

Formal science is an area of study that generates knowledge using formal systems. A formal system is an abstract structure used for inferring theorems from axioms according to a set of rules. It includes mathematics, systems theory, and theoretical computer science. The formal sciences share similarities with the other two branches by relying on objective, careful, and systematic study of an area of knowledge. They are, however, different from the empirical sciences as they rely exclusively on deductive reasoning, without the need for empirical evidence, to verify their abstract concepts. The formal sciences are therefore a priori disciplines and because of this, there is disagreement on whether they constitute a science. Nevertheless, the formal sciences play an important role in the empirical sciences. Calculus, for example, was initially invented to understand motion in physics. Natural and social sciences that rely heavily on mathematical applications include mathematical physics, chemistry, biology, finance, and economics.

Applied science

Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge to attain practical goals and includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine. Engineering is the use of scientific principles to invent, design and build machines, structures and technologies. Science may contribute to the development of new technologies. Medicine is the practice of caring for patients by maintaining and restoring health through the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of injury or disease. The applied sciences are often contrasted with the basic sciences, which are focused on advancing scientific theories and laws that explain and predict events in the natural world.

Computational science applies computing power to simulate real-world situations, enabling a better understanding of scientific problems than formal mathematics alone can achieve. The use of machine learning and artificial intelligence is becoming a central feature of computational contributions to science, for example in agent-based computational economics, random forests, topic modeling and various forms of prediction. However, machines alone rarely advance knowledge as they require human guidance and capacity to reason; and they can introduce bias against certain social groups or sometimes underperform against humans.

Interdisciplinary science

Interdisciplinary science involves the combination of two or more disciplines into one, such as bioinformatics, a combination of biology and computer science or cognitive sciences. The concept has existed since the ancient Greek period and it became popular again in the 20th century.

Scientific research

Scientific research can be labelled as either basic or applied research. Basic research is the search for knowledge and applied research is the search for solutions to practical problems using this knowledge. Most understanding comes from basic research, though sometimes applied research targets specific practical problems. This leads to technological advances that were not previously imaginable.

Scientific method

Scientific research involves using the scientific method, which seeks to objectively explain the events of nature in a reproducible way. Scientists usually take for granted a set of basic assumptions that are needed to justify the scientific method: there is an objective reality shared by all rational observers; this objective reality is governed by natural laws; these laws were discovered by means of systematic observation and experimentation. Mathematics is essential in the formation of hypotheses, theories, and laws, because it is used extensively in quantitative modelling, observing, and collecting measurements. Statistics is used to summarise and analyse data, which allows scientists to assess the reliability of experimental results.

In the scientific method an explanatory thought experiment or hypothesis is put forward as an explanation using parsimony principles and is expected to seek consilience – fitting with other accepted facts related to an observation or scientific question. This tentative explanation is used to make falsifiable predictions, which are typically posted before being tested by experimentation. Disproof of a prediction is evidence of progress. Experimentation is especially important in science to help establish causal relationships to avoid the correlation fallacy, though in some sciences such as astronomy or geology, a predicted observation might be more appropriate.

When a hypothesis proves unsatisfactory it is modified or discarded. If the hypothesis survives testing, it may become adopted into the framework of a scientific theory, a validly reasoned, self-consistent model or framework for describing the behaviour of certain natural events. A theory typically describes the behaviour of much broader sets of observations than a hypothesis; commonly, a large number of hypotheses can be logically bound together by a single theory. Thus, a theory is a hypothesis explaining various other hypotheses. In that vein, theories are formulated according to most of the same scientific principles as hypotheses. Scientists may generate a model, an attempt to describe or depict an observation in terms of a logical, physical or mathematical representation, and to generate new hypotheses that can be tested by experimentation.

While performing experiments to test hypotheses, scientists may have a preference for one outcome over another. Eliminating the bias can be achieved through transparency, careful experimental design, and a thorough peer review process of the experimental results and conclusions. After the results of an experiment are announced or published, it is normal practice for independent researchers to double-check how the research was performed, and to follow up by performing similar experiments to determine how dependable the results might be. Taken in its entirety, the scientific method allows for highly creative problem solving while minimising the effects of subjective and confirmation bias. Intersubjective verifiability, the ability to reach a consensus and reproduce results, is fundamental to the creation of all scientific knowledge.

Scientific literature

Scientific research is published in a range of literature. Scientific journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions, serving as an archival record of science. The first scientific journals, Journal des sçavans followed by Philosophical Transactions, began publication in 1665. Since that time the total number of active periodicals has steadily increased. In 1981, one estimate for the number of scientific and technical journals in publication was 11,500.

Most scientific journals cover a single scientific field and publish the research within that field; the research is normally expressed in the form of a scientific paper. Science has become so pervasive in modern societies that it is considered necessary to communicate the achievements, news, and ambitions of scientists to a wider population.

Challenges

The replication crisis is an ongoing methodological crisis that affects parts of the social and life sciences. In subsequent investigations, the results of many scientific studies have been proven to be unrepeatable. The crisis has long-standing roots; the phrase was coined in the early 2010s as part of a growing awareness of the problem. The replication crisis represents an important body of research in metascience, which aims to improve the quality of all scientific research while reducing waste.

An area of study or speculation that masquerades as science in an attempt to claim legitimacy that it would not otherwise be able to achieve is sometimes referred to as pseudoscience, fringe science, or junk science. Physicist Richard Feynman coined the term "cargo cult science" for cases in which researchers believe, and at a glance, look like they are doing science but lack the honesty to allow their results to be rigorously evaluated. Various types of commercial advertising, ranging from hype to fraud, may fall into these categories. Science has been described as "the most important tool" for separating valid claims from invalid ones.

There can also be an element of political or ideological bias on all sides of scientific debates. Sometimes, research may be characterised as "bad science", research that may be well-intended but is incorrect, obsolete, incomplete, or over-simplified expositions of scientific ideas. The term "scientific misconduct" refers to situations such as where researchers have intentionally misrepresented their published data or have purposely given credit for a discovery to the wrong person.

Philosophy of science

There are different schools of thought in the philosophy of science. The most popular position is empiricism, which holds that knowledge is created by a process involving observation; scientific theories generalise observations. Empiricism generally encompasses inductivism, a position that explains how general theories can be made from the finite amount of empirical evidence available. Many versions of empiricism exist, with the predominant ones being Bayesianism and the hypothetico-deductive method.

Another approach, instrumentalism, emphasises the utility of theories as instruments for explaining and predicting phenomena. It views scientific theories as black boxes, with only their input (initial conditions) and output (predictions) being relevant. Consequences, theoretical entities, and logical structure are claimed to be things that should be ignored. Close to instrumentalism is constructive empiricism, according to which the main criterion for the success of a scientific theory is whether what it says about observable entities is true.

Thomas Kuhn argued that the process of observation and evaluation takes place within a paradigm, a logically consistent "portrait" of the world that is consistent with observations made from its framing. He characterised normal science as the process of observation and "puzzle solving", which takes place within a paradigm, whereas revolutionary science occurs when one paradigm overtakes another in a paradigm shift. Each paradigm has its own distinct questions, aims, and interpretations. The choice between paradigms involves setting two or more "portraits" against the world and deciding which likeness is most promising. A paradigm shift occurs when a significant number of observational anomalies arise in the old paradigm and a new paradigm makes sense of them. That is, the choice of a new paradigm is based on observations, even though those observations are made against the background of the old paradigm. For Kuhn, acceptance or rejection of a paradigm is a social process as much as a logical process. Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism.

Finally, another approach often cited in debates of scientific scepticism against controversial movements like "creation science" is methodological naturalism. Naturalists maintain that a difference should be made between natural and supernatural, and science should be restricted to natural explanations. Methodological naturalism maintains that science requires strict adherence to empirical study and independent verification.

Scientific community

The scientific community is a network of interacting scientists who conduct scientific research. The community consists of smaller groups working in scientific fields. By having peer review, through discussion and debate within journals and conferences, scientists maintain the quality of research methodology and objectivity when interpreting results.

Scientists

Scientists are individuals who conduct scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest. In modern times, many professional scientists are trained in an academic setting and, upon completion, attain an academic degree, with the highest degree being a doctorate such as a Doctor of Philosophy or PhD. Many scientists pursue careers in various sectors of the economy such as academia, industry, government, and nonprofit organisations.

Scientists exhibit a strong curiosity about reality and a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the benefit of health, nations, the environment, or industries. Other motivations include recognition by their peers and prestige. In modern times, many scientists have advanced degrees in an area of science and pursue careers in various sectors of the economy, such as academia, industry, government, and nonprofit environments.

Science has historically been a male-dominated field, with notable exceptions. Women in science faced considerable discrimination in science, much as they did in other areas of male-dominated societies. For example, women were frequently passed over for job opportunities and denied credit for their work.[224] The achievements of women in science have been attributed to the defiance of their traditional role as labourers within the domestic sphere.

Learned societies

Learned societies for the communication and promotion of scientific thought and experimentation have existed since the Renaissance. Many scientists belong to a learned society that promotes their respective scientific discipline, profession, or group of related disciplines. Membership may either be open to all, require possession of scientific credentials, or conferred by election. Most scientific societies are nonprofit organisations, and many are professional associations. Their activities typically include holding regular conferences for the presentation and discussion of new research results and publishing or sponsoring academic journals in their discipline. Some societies act as professional bodies, regulating the activities of their members in the public interest, or the collective interest of the membership.

The professionalisation of science, begun in the 19th century, was partly enabled by the creation of national distinguished academies of sciences such as the Italian Accademia dei Lincei in 1603, the British Royal Society in 1660, the French Academy of Sciences in 1666, the American National Academy of Sciences in 1863, the German Kaiser Wilhelm Society in 1911, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1949. International scientific organisations, such as the International Science Council, are devoted to international cooperation for science advancement.

Awards

Science awards are usually given to individuals or organisations that have made significant contributions to a discipline. They are often given by prestigious institutions; thus, it is considered a great honour for a scientist receiving them. Since the early Renaissance, scientists have often been awarded medals, money, and titles. The Nobel Prize, a widely regarded prestigious award, is awarded annually to those who have achieved scientific advances in the fields of medicine, physics, and chemistry.

Society

Funding and policies

Scientific research is often funded through a competitive process in which potential research projects are evaluated and only the most promising receive funding. Such processes, which are run by government, corporations, or foundations, allocate scarce funds. Total research funding in most developed countries is between 1.5% and 3% of GDP. In the OECD, around two-thirds of research and development in scientific and technical fields is carried out by industry, and 20% and 10%, respectively, by universities and government. The government funding proportion in certain fields is higher, and it dominates research in social science and the humanities. In less developed nations, the government provides the bulk of the funds for their basic scientific research.

Many governments have dedicated agencies to support scientific research, such as the National Science Foundation in the United States, the National Scientific and Technical Research Council in Argentina, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Australia, National Centre for Scientific Research in France, the Max Planck Society in Germany, and National Research Council in Spain. In commercial research and development, all but the most research-orientated corporations focus more heavily on near-term commercialisation possibilities than research driven by curiosity.

Science policy is concerned with policies that affect the conduct of the scientific enterprise, including research funding, often in pursuance of other national policy goals such as technological innovation to promote commercial product development, weapons development, health care, and environmental monitoring. Science policy sometimes refers to the act of applying scientific knowledge and consensus to the development of public policies. In accordance with public policy being concerned about the well-being of its citizens, science policy's goal is to consider how science and technology can best serve the public. Public policy can directly affect the funding of capital equipment and intellectual infrastructure for industrial research by providing tax incentives to those organisations that fund research.

Education and awareness

Science education for the general public is embedded in the school curriculum, and is supplemented by online pedagogical content (for example, YouTube and Khan Academy), museums, and science magazines and blogs. Scientific literacy is chiefly concerned with an understanding of the scientific method, units and methods of measurement, empiricism, a basic understanding of statistics (correlations, qualitative versus quantitative observations, aggregate statistics), and a basic understanding of core scientific fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, ecology, geology, and computation. As a student advances into higher stages of formal education, the curriculum becomes more in depth. Traditional subjects usually included in the curriculum are natural and formal sciences, although recent movements include social and applied science as well.

The mass media face pressures that can prevent them from accurately depicting competing scientific claims in terms of their credibility within the scientific community as a whole. Determining how much weight to give different sides in a scientific debate may require considerable expertise regarding the matter. Few journalists have real scientific knowledge, and even beat reporters who are knowledgeable about certain scientific issues may be ignorant about other scientific issues that they are suddenly asked to cover.

Science magazines such as New Scientist, Science & Vie, and Scientific American cater to the needs of a much wider readership and provide a non-technical summary of popular areas of research, including notable discoveries and advances in certain fields of research. The science fiction genre, primarily speculative fiction, can transmit the ideas and methods of science to the general public. Recent efforts to intensify or develop links between science and non-scientific disciplines, such as literature or poetry, include the Creative Writing Science resource developed through the Royal Literary Fund.

Anti-science attitudes

While the scientific method is broadly accepted in the scientific community, some fractions of society reject certain scientific positions or are sceptical about science. Examples are the common notion that COVID-19 is not a major health threat to the US (held by 39% of Americans in August 2021) or the belief that climate change is not a major threat to the US (also held by 40% of Americans, in late 2019 and early 2020). Psychologists have pointed to four factors driving rejection of scientific results:

- Scientific authorities are sometimes seen as inexpert, untrustworthy, or biased.

- Some marginalised social groups hold anti-science attitudes, in part because these groups have often been exploited in unethical experiments.

- Messages from scientists may contradict deeply held existing beliefs or morals.

- The delivery of a scientific message may not be appropriately targeted to a recipient's learning style.

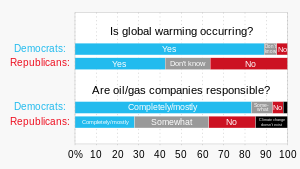

Anti-science attitudes often seem to be caused by fear of rejection in social groups. For instance, climate change is perceived as a threat by only 22% of Americans on the right side of the political spectrum, but by 85% on the left. That is, if someone on the left would not consider climate change as a threat, this person may face contempt and be rejected in that social group. In fact, people may rather deny a scientifically accepted fact than lose or jeopardise their social status.

Politics