The soul is the purported immaterial aspect or essence of a living being. It is typically believed to be immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that describe the relationship between the soul and the body are interactionism, parallelism, and epiphenomenalism. Anthropologists and psychologists have found that most humans are naturally inclined to believe in the existence of the soul and that they have interculturally distinguished between souls and bodies.

The soul has been the central area of interest in philosophy since ancient times. Socrates envisioned the soul to possess a rational faculty, its practice being man's most godlike activity. Plato believed the soul to be the person's real self, an immaterial and immortal dweller of our lives that continues and thinks even after death. Aristotle sketched out the soul as the "first actuality" of a naturally organized body—form and matter arrangement allowing natural beings to aspire to full actualization.

Medieval philosophers expanded upon these classical foundations. Avicenna distinguished between the soul and the spirit, arguing that the soul's immortality follows from its nature rather than serving as a purpose to fulfill. Following Aristotelian principles, Thomas Aquinas understood the soul as the first actuality of the living body but maintained that it could exist without a body since it has operations independent of corporeal organs. During the Age of Enlightenment, Immanuel Kant defined the soul as the "I" in the most technical sense, holding that we can prove that "all properties and actions of the soul cannot be recognized from materiality".

Different religions conceptualize souls in different ways. Buddhism generally teaches the non-existence of a permanent self (anattā), contrasting with Christianity's belief in an eternal soul that experiences death as a transition to God's presence in heaven. Hinduism views the Ātman ('self', 'essence') as identical to Brahman in some traditions, while Islam uses two terms—rūḥ and nafs—to distinguish between the divine spirit and a personal disposition. Jainism considers the soul (jīva) to be an eternal but changing form until liberation, while Judaism employs multiple terms such as nefesh and neshamah to refer to the soul. Sikhism regards the soul as part of God (Waheguru), Shamanism often embraces soul dualism with "body souls" and "free souls", while Taoism recognizes dual soul types (hun and po).

Etymology

The English noun soul stems from the Old English sāwl. The earliest attestations reported in the Oxford English Dictionary are from the 8th century. In the Vespasian Psalter 77.50, it means 'life' or 'animate existence'. In King Alfred's translation of De Consolatione Philosophiae, it is used to refer to the immaterial, spiritual, or thinking aspect of a person, as contrasted with the person's physical body. The Old English word is cognate with other historical Germanic terms for the same idea, including Old Frisian sēle, sēl (which could also mean 'salvation', or 'solemn oath'), Gothic saiwala, Old High German sēula, sēla, Old Saxon sēola, and Old Norse sála. Present-day cognates include Dutch ziel and German Seele.

Religion

Buddhism

The concepts of anatman (not-self) is fundamental to Buddhism. Early Buddhists were suspicious about the spiritual value of a soul. They wanted to clearly reject the notion of a mortal body and eternal soul dualism that Jainism posited and that lead to ascetics starving themselves to death to free the soul from the mortal prison. From a historical perspective, the doctrine of anatman evolved out of two main philosophico-religious beliefs: eternalism (sassata-vada) and annihilationism (anuyoga). The eternalists assert the eternity of the soul; ritual purity, celestial beings, heaven and hell, mortification of the body, etc. In contrast, the annihilationists deny the immortality of the soul and believe that the soul only exists as long as the body does. Since they believe that the soul dies with the body, they prescribe practising self-indulgence (kamasukhallikanuyoga) in order to enjoy pleasures experienced through the senses. The Buddha rejects both views and identifies their origins to be caused by two cravings: Desire for immortality drags people to eternalism, when life is pleasurable, while when unpleasant states lead to annihiliation because of the craving for self-discontinuity. Buddha identifies both views as soul-theories, as both identify a self through craving.

The idea of an unchanging soul conflicts with the principles of dependent origination and cessation of all of the five aggregates. Due to their impermanence, they are considered "empty" or "without essence". Through the lens of impermanence, Buddhists recognize that all phenomena—whether physical or mental—are in a continuous cycle of arising and dissolving, with nothing being permanent, including the perception of a self or soul. In Buddhism, the only absolute is Śūnyatā. The self is a retrospective evaluation of sensual experience. This sensory experience then leads to craving and the formation of the thought "this is mine", whereby creating the notion of a self. It is this continuity of craving to a self, which gives raise to a new birth. Buddhists regard the identification of an independent soul with perception as mistaken, since our perception of the world depends on the sense organs. In the Cetana-sutta, the flow of consciousness maintains the connection between one birth to another, and also determines the conditions of the conceptions into the mother's womb, where they forget about their previous lives. The Mahavedalla-sutta mentions three modes of self-continuity: sensual self-continuity (kama-bhava), fine-material mode (rupa-bhava), and immaterial self-continuity (arupa-bhava), the latter two take place among those who practise absorption meditations (jhana) and become brahmas.

However, even this transmission of consciousness cannot be identified with a soul, for the very possibility of losing consciousness would be inexplicable. Were there a soul, Buddhists would associate it with something entirely devoid of sensibility—yet such an entity would lack any basis for being identified as "me". Another argument against an autonomous soul is that it could will itself to never die or get sick, however, death and sickness happen against the will of individuals. The final argument is that, within Buddhist thought, nothing has been identified as unchanging or permanent. Since consciousness too is impermanent, an unchanging soul cannot exist. Thus, every individual is a complex interplay of physical and mental phenomena, all dependent on countless conditions; once these phenomena and conditions are removed, no enduring self can be found.

Unanswerable question

The Buddha left ten questions unanswered, one of which concerned the existence of a soul ("Is the soul one thing and the body another?" and "Who is it that is reborn?"). This led some people believe that the Buddha only rejected a soul defined through one (or more) of the five aggregates (Skandha). Another interpretation holds that he remained silent, because the Buddha considered the question irrelevant to the pursuit of enlightenment. Whether he knew the answer remains a matter of debate. Yet another view argues that the Buddha remained silent, because the question itself is invalid.

Those who argue that the Buddha affirmed a self, independent from body and mind, as proposed by the eternalists or annihilists, argue that the soul is something transcending the five aggregates. Some Buddhists of the Mahayana tradition believe that the soul is not absolute, but immortal; the soul cannot die, although influenced by karma, since the soul is unborn and unconditioned. In support for that view, Christopher Gowan points at Buddhist texts possibly implying some sort of self, such as references to personal pronouns, and the need for a self who suffers in order to aim for release in nirvana. Due to the implicit references in the Buddhist doctrines, Gowan also rejects the view that they are merely conventions of speech, rather the best way to understand Buddha's teachings coherently would be to distinguishing between a substantial self and an ever changing self beyond the five aggregates. The Buddha would have rejected the former, but implicitly affirmed the latter.

In contrast, others hold that the Buddha remained silent on this matter, because they are invalid questions. When asked such a question ("Who is reborn?") the existence of a self is presupposed. However, if souls do not exist, no one can be reborn in the first place, and thus, there is no accurate answer to the question. This view also disapproves of later responses within traditional Buddhist schools, such as Theravada, who answered the question on identity in paradoxical terms, yet whereby implicitly affirming some sort of Self or soul.

Two Truths

In the early Buddhist text Milinda's Questions, the nature of the enduring self is examined through a dialogue between the Greek king Milinda and the monk Nāgasena. When asked about his identity, Nāgasena explains that in truth, there is no Nāgasena, because his name is merely a label. To illustrate his point, he refers to Milinda's chariot and asks whether its essence lies in the axle, the wheels, or the framework. Milinda concedes that the chariot's essence is not found in any single part, but maintains that the term 'chariot' is still meaningful, as it refers to the combination of all its parts. Nāgasena agrees—and adds that this is precisely his point: there is no Nāgasena beyond the five aggregates that constitute him. Like the chariot, the person is a conventional designation applied to a collection of interdependent components.

The example of Milinda's chariot relates to the Buddhist Two truths doctrine. Accordingly, the conventional truth refers to phenomenal truths of the perceptive world, including persons, but ultimately, they are devoid of essence and independent existence. Upon realization of the self as a mere convention, fear of death and attachment to self-permanence would cease, as there is no self to attach to in the first place. This interpretation of Milinda's Questions was also compared to David Hume's bundle theory.

Christianity

The Bible teaches that upon death, souls are immediately welcomed into heaven, having received forgiveness of sins through accepting Christ as Savior. Believers experience death as a transition where they depart their physical bodies to dwell in God's presence. While the soul is united with God at death, the physical body remains in the grave, awaiting resurrection. At the time of the resurrection, the body will be raised, perfected, and reunited with the soul. This fully restored, glorified unity of body and spirit will then exist eternally in the renewed creation described in Revelation 21–22.

Paul the Apostle used psychē (ψυχή) and pneuma (πνεῦμα) specifically to distinguish between the Jewish notions of nephesh (נפש), meaning soul, and ruah (רוח), meaning spirit (also in the Septuagint, e.g. Genesis 1:2 רוּחַ אֱלֹהִים = πνεῦμα θεοῦ = spiritus Dei = 'the Spirit of God'). This has led some Christians to espouse a trichotomic view of humans, which characterizes humans as consisting of a body (soma), soul (psyche), and spirit (pneuma). However, others believe that "spirit" and "soul" are used interchangeably in many biblical passages and so hold to dichotomy: the view that each human comprises a body and a soul. The author of Hebrews said, "For the word of God is living and active and sharper than any two-edged sword, and piercing as far as the division of soul and spirit."

The "origin of the soul" has proved a vexing question in Christianity. The major theories put forward include soul creationism, traducianism, and pre-existence. According to soul creationism, God creates each individual soul directly, either at the moment of conception or at some later time. According to traducianism, the soul comes from the parents by natural generation. According to the pre-existence theory, the soul exists before the moment of conception. There have been differing thoughts regarding whether human embryos have souls from conception, or whether there is a point between conception and birth where the fetus acquires a soul, consciousness, and personhood.

Corruptionism is the view that following physical death, the human being ceases to exist (until resurrection) but their soul persists in the afterlife. Survivalism holds that both the human being and their soul persist in the afterlife, as distinct entities, with the soul constituting the human. Most Thomists hold to the corruptionist view, arguing that a human person is a composite of matter and soul. Survivalists argue that while a person is not identical to their soul, it is sufficient to constitute a person. In recent years, a middle view has been put forward: that the separated soul is an incomplete person. It argues that the soul meets most of the criteria of a person but that the survivalist view fails to capture the unnaturalness of a person surviving death.

Hinduism

Ātman is a Sanskrit word that means inner self or soul. In Hindu philosophy, especially in the Vedanta school of Hinduism, Ātman is the first principle, the true self of an individual beyond identification with phenomena, the essence of an individual. In order to attain liberation (moksha), a human being must acquire self-knowledge (ātma jñāna), which is to realize that one's true self (Ātman) is identical with the transcendent self Brahman according to Advaita Vedanta. The six orthodox schools of Hinduism believe that there is Ātman ('self', 'essence') in every being.

In Hinduism and Jainism, a jīva (Sanskrit: जीव, jīva; Hindi: जीव, jīv) is a living being, or any entity imbued with a life force. The concept of jīva in Jainism is similar to Ātman in Hinduism; however, some Hindu traditions differentiate between the two concepts, with jīva considered as an individual self, but with Ātman as that which is the universal unchanging self that is present in all living beings and everything else as the metaphysical Brahman. The latter is sometimes referred to as jīva-ātman (a soul in a living body).

Islam

Islam uses two words for the soul: rūḥ (translated as 'spirit', 'consciousness', 'pneuma', or 'soul') and nafs (translated as 'self', 'ego', 'psyche', or 'soul'). The two terms are frequently used interchangeably, although rūḥ is more often used to denote the divine spirit or "the breath of life", while nafs designates one's disposition or characteristics. The Taj al-'Arus min Jawahir al-Qamus lists several meanings of nafs, including two from the Lisān al-ʿArab, including spirit, self, desire, evil eye, disdain, body. Lane's Lexicon notes that humans consist of nafs and rūḥ. The former applies to the mind and the latter to life. Attribution of nafs to God (Allah) is avoided. Al-Bag̲h̲dādī also rejected that God has rūḥ in order to have life, as Christian beliefs, and proposes that all spirits (arwāḥ) are created.

In the Quran, nafs (plurals: anfus and nufūs) refers in most cases to the person or a self. It is used for both humans and djinn (but not to angels). When referring to the soul it is of three types: the commanding self (ammāra bi ’l sūʾ), remniscient of the Hebrew nefes̲h̲ (physical appetite) and the Pauline idea of "flesh" (φυχή) and is always evil, its greed must be feared, and it must be restraint. The accusing self (lawwāma) is the soul of the deserters. Lastly, there is the tranquil soul (muṭmaʾinna). This typology of the soul is the foundation for later Muslim treatises on ethics and psychology.

Islamic philosophy (falsafa)

Most Muslim philosophers (Arabic: falsafa), aligned with their Greek predecessors, broadly accepted that the soul is composed of non-rational and rational elements. The non-rational dimension was subdivided into the vegetative and animal souls, while the rational aspect was split into the practical and theoretical intellects. While all agreed that the non-rational soul is tied to the body, opinions diverged on the rational part: some deemed it immaterial and naturally independent of the body, whereas others asserted the entirely material nature of all soul components. Ibn Hazm uses nafs and rūḥ interchangeably. He also rejected metempsychosis that all souls were already created then the angels were commanded to bow before Adam, waiting in Barzakh until the blown into the embryo.

Consensus held that during its union with the body, the non-rational soul governs bodily functions, the practical intellect manages earthly and corporeal matters, and the theoretical intellect pursues knowledge of universal, eternal truths. These thinkers maintained that the soul’s highest purpose or happiness lies in transcending bodily desires to contemplate timeless universal principles. All agreed the non-rational soul is mortal—created and inevitably perishable. However, views on the rational soul’s fate varied: al-Farabi suggested its eternal survival was uncertain; Ibn Sina claimed it was uncreated and immortal; and Ibn Rushd argued that the entire soul, including all its parts, is transient and ultimately ceases to exist.

For Ibn Arabi, the soul is human potential, and the purpose of life is the actualization of that potential. Human experience is whereby always between the body (jism) and spirit (rūḥ), and thus the indivual experience is limited to imagination (nafsânî). Wavering between its body and spirit, the soul can choose (free-will) between either ascending to realization or descending to the materialistic mind, which Ibn Arabi compares to Muhammad's Night Journey (miʿrāj). This allows the soul to determine its own tragectory in a karmic chain of causalities, towards paradisical or infernal levels, depending on the person's understanding, traits, and actions.

Theology (kalam)

Al-Ghazali (fl. 11th century) reconciles the Sunni views on the soul with Avicennan philosophy (falsafa). Al-Ghazali defines human as a spiritual substance (d̲j̲awhar rūḥānī), neither confined, nor joined, nor separated from the body. It possesses knowledge and perception. He identifies the immaterial self with the al-nafs al-muṭmaʾinna and al-rūḥ al-amīn of the Quran and nafs for bodily desires which must be disciplined. He, however, refuses to elaborate on the deepest nature of the soul, as he claims it is forbidden by sharīʿah, on grounds that it is beyond comprehension.

According to al-Ghazali, nafs consists of three elements: animals, devils, and angels. The term for the self or soul is heart (ḳalb). The nafs, in al-Ghazali's concept of the soul, is best be understood as psyche, a 'vehicle' (markab) of the soul, but yet distinct. The animalistic parts of nafs is concerned with bodily functions, such as eating and sleeping, the devilish part with deceit and lies, and the angelic part with comtemplating the signs of God and preventing lust and anger. Accordingly, the inclinations towards following either nafs or the intellect is associated with supernatural agents: the angels inspire to follow the intellect (ilhām) and the devils tempt to give in into evil (waswās).

Al-Baydawi's psychology shows influence from the writings of al-Ghazali, whom he also mentions explicitly. His classification of souls is elaborated in his Ṭawāliʿ al-anwār, authored c. 1300. Like, al-Ghazali, he is in support of the existence of the soul as independent from the body and offers both rational as well as Quranic evidence. He further adds that nafs is created when the body is completed, but is not embodied itself, and is connected with rūḥ.

When discussing the souls, al-Baydawi establishes a cosmological hierarchy of heavenly Intellects. Accordingly, God, in his unity (tawḥīd), first creates the Intellect (ʿaḳl), which is neither body, nor form, but the cause of all other potentialities. From this Intellect, a third Intellect is produced up to the tenth Intellect, which in turn influences the elements and bring fourth the spirits (arwāḥ). Below these Intellects are the "souls of the spheres" (al-nufūs al-falakiyya) identified with the heavenly angels. Below them are the incorporeal earthly angels, both good and evil angels (al-kurūbiyyūn and al-s̲h̲ayāṭīn), angels in control of the elements and the "souls of reasoning" (anfus nāṭiḳa), as well as djinn.

Ismailism

Ismaili cosmology is largely described through Neo-Platonic and Gnostic ideas. Two influential Ismaili teachers are Abu Ya'qub al-Sijistani during the 10th century and Nasir Khusraw during the 11th. One of Sijistani's key doctrines is the immateriality of the soul, which belongs to the spiritual domain but is captured in the body of the material world. In his soteriological teachings, the soul needs to discard sensual pleasures for the sake of intellectual gratification through spiritual ascension. One of Sijistani's arguments is, that sensual pleasure is finite, and thus cannot be part of the eternal soul. Although not made explicit by Sijistani himself, other Ismaili authors propose that a soul attached to material pleasure will be reborn in another sensual body on earth, first as a dark-skinned person, a Berber, or a Turk, then as an animals, an insects, or a plant, all believed to be progressively less likely to pursue spiritual or intellectual virtues.

In this context, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi identifies the earthly world with sijjīn. The zabaniyah are identified with the nineteen evil forces that distract human being from heavenly truths and diverge them to material and sensual concerns, including distorted imagination (khayāl). The paradisical houris are conceptualized as items of knowledge from the spiritual world, the soul is united with in a form of metaphorical marriage, per Surah 44:54. This type of knowledge is inaccessible to those souls remaining in the earthly domain or hell.

Nasir Khusraw equates the rational soul of humans with a spirit potentially angel and demon. The soul is a potential angel or potential demon, depending on their obedience to God's law. The obedient soul is growing to a potential angel and becomes an actual angel upon death, while the soul seeking out sensual delights is a potential demon and turns into an actual demon in the next world.

Jainism

In Jainism, every living being, from plant or bacterium to human, has a soul and the concept forms the very basis of Jainism. According to Jainism, there is no beginning or end to the existence of soul. It is eternal in nature and changes its form until it attains liberation. In Jainism, jīva is the immortal essence or soul of a living organism, such as human, animal, fish, or plant, which survives physical death. The term ajīva in Jainism means 'not soul', and represents matter (including body), time, space, non-motion and motion. In Jainism, a jīva is either samsari (mundane, caught in cycle of rebirths) or mukta ('liberated').

According to this belief until the time the soul is liberated from the saṃsāra (cycle of repeated birth and death), it gets attached to one of these bodies based on the karma ('actions') of the individual soul. Irrespective of which state the soul is in, it has got the same attributes and qualities. The difference between the liberated and non-liberated souls is that the qualities and attributes are manifested completely in case of siddha ('liberated soul') as they have overcome all karmic bondage, whereas in case of non-liberated souls they are partially exhibited. Souls who rise victorious over wicked emotions while still remaining within physical bodies are referred to as arihants.

Concerning the Jain view of the soul, Virchand Gandhi said that, "the soul lives its own life, not for the purpose of the body, but the body lives for the purpose of the soul. If we believe that the soul is to be controlled by the body then soul misses its power."[84]

Judaism

The Hebrew terms נפש nefesh ('living being'), רוח ruach ('wind'), נשמה neshamah ('breath'), חיה chayah ('life') and יחידה yechidah ('singularity') are used to describe the soul or spirit.

Jewish beliefs concerning the concept and nature of the soul are complicated by a lack of singularly authoritative traditions and differing beliefs in an afterlife. The conception of an immortal soul separate from and capable of surviving a human being after death was not present in early Jewish belief, but became prevalent by the onset of the Common Era. This conception of the soul differed from that of the Greek, and later Christian, belief in that the soul was viewed an ontological substance which was intrinsically inseparable from the human body. At the same time, a burgeoning belief in an afterlife required some form of continued existence following the end of mortal life in order to partake in the world to come. This need for apparent dichotomy is reflected in the Talmud, where the biblical psychophysical unity of the soul remains, but the possibility of the soul's simultaneous existence on both a physical and a spiritual level is embraced. This essential paradox is only reinforced by subsequent Rabbinical works. Ultimately, the specific nature of the soul was of secondary concern to rabbinical authorities, and indeed remains as such in most modern traditions.

As spiritual and mystic traditions developed, the Jewish concept of the soul underwent a number of changes. Kabbalah and other mystic traditions go into greater detail into the nature of the soul. Kabbalah separates the soul into five elements, corresponding to the five worlds:

- Nefesh, related to natural instinct.

- Ruach, related to emotion.

- Neshamah, related to intellect.

- Chayah, which gazes at the transcendence of God.

- Yechidah, essence of the soul, which is bound to God.

Kabbalah proposed a concept of reincarnation, the gilgul (nefesh habehamit, the 'animal soul'). Some Jewish traditions assert that the soul is housed in the luz bone, although traditions disagree as to whether it is the atlas at the top of the spine, or the sacrum at bottom of the spine.

Shamanism

Soul dualism, also called "multiple souls" or "dualistic pluralism", is a common belief in Shamanism, and is essential in the universal and central concept of "soul flight" (also called "soul journey", "out-of-body experience", "ecstasy", or "astral projection"). It involves the belief that humans have two or more souls, generally termed the "body soul" (or "life soul"), and the "free soul". The former is linked to bodily functions and awareness when awake, while the latter can freely wander during sleep or trance states. In some cases, there are a plethora of soul types with different functions. Soul dualism and multiple souls appear prominently in the traditional animistic beliefs of the Austronesian peoples, the Chinese people (hun and po), the Tibetan people, most African peoples, most Native North Americans, ancient South Asian peoples, Northern Eurasian peoples, and among Ancient Egyptians (the ka and ba).

Belief in soul dualism is found throughout most Austronesian shamanistic traditions. The reconstructed Proto-Austronesian word for the 'body soul' is *nawa ('breath', 'life', or 'vital spirit'). The body-soul is located somewhere in the abdominal cavity, often in the liver or the heart (Proto-Austronesian *qaCay). The "free soul" is located in the head. Its names are usually derived from Proto-Austronesian *qaNiCu ('ghost', 'spirit [of the dead]'), which also apply to other non-human nature spirits. The "free soul" is also referred to in names that literally mean 'twin' or 'double', from Proto-Austronesian *duSa ('two'). A virtuous person is said to be one whose souls are in harmony with each other, while an evil person is one whose souls are in conflict.

The "free soul" is said to leave the body and journey to the spirit world during sleep, trance-like states, delirium, insanity, and at death. The duality is also seen in the healing traditions of Austronesian shamans, where illnesses are regarded as a "soul loss"—and thus to heal the sick, one must "return" the "free soul" (which may have been stolen by an evil spirit or got lost in the spirit world) into the body. If the "free soul" cannot be returned, the afflicted person dies or goes permanently insane. The shaman heals within the spiritual dimension by returning 'lost' parts of the human soul from wherever they have gone. The shaman also cleanses excess negative energies, which confuse or pollute the soul.

In some ethnic groups, there can be more than two souls. Among the Tagbanwa people of the Philippines a person is said to have six souls—the "free soul" (which is regarded as the "true" soul) and five secondary souls with various functions. Several Inuit groups believe that a person has more than one type of soul. One is associated with respiration, the other can accompany the body as a shadow. In some cases, it is connected to shamanistic beliefs among the various Inuit groups. Caribou Inuit groups also believed in several types of souls.

Sikhism

In Sikhism, the soul, referred to as the Ātman, is understood as a pure consciousness without any content. The soul is considered to be eternal and inherently connected to the divine (Paramatman), although its journey is shaped by karma—the cumulative effect of one's actions, thoughts, and deeds. According to Sikh teachings, the soul undergoes cycles of rebirth (transmigration) until it achieves liberation (mukti) from this cycle, a process governed by the principles of divine order (hukam) and grace (nadar).

The cycle of rebirth is influenced by the individual's attachment to worldly desires and ego (haumai), which obscures the soul's innate connection to the divine. Sikh scripture warns that preoccupation with material wealth, familial ties, or sensory pleasures at the moment of death can lead to rebirth in lower life forms, such as animals or spirits. Conversely, meditation on God's name (Nam Simran) and remembrance of the divine (Waheguru) during life—and especially at death—enable the soul to merge with the eternal truth (Sach Khand), ending the cycle of reincarnation.

Central to Sikh doctrine is the belief that while karma determines the soul's trajectory, divine grace can transcend karmic limitations. The Guru Granth Sahib claims that liberation ultimately depends on God's will. Ethical living, including honest labor (Kirat Karo), sharing resources (Vand Chhako), and community service (seva).

Taoism

In Taoism, the idea of the "soul" is not a single, unchanging entity like in many Western traditions. Instead, it is seen as a dynamic balance of energies. Two key parts are the hun and po. The hun is the "ethereal soul", linked to light, spiritual awareness, and the mind. It is considered yang ('active, upward energy') and is said to depart the body after death. The po is the "corporeal soul", tied to the body, instincts, and physical senses. It is yin ('passive, earthly energy') and stays with the body after death, dissolving back into the earth over time.

There is significant scholarly debate about the Taoist understanding of death. The process of death itself is described as shijie or "release from the corpse", but what happens after is described variously as transformation, immortality or ascension of the soul to heaven. For example, the Yellow Emperor was said to have ascended directly to heaven in plain sight, while the thaumaturge Ye Fashan was said to have transformed into a sword and then into a column of smoke which rose to heaven.

Taoist texts such as the Zhuangzi suggest the soul is not separate from the natural world but part of the flow of the Tao (the universal principle). One passage states, "Heaven and earth were born at the same time I was, and the ten thousand things are one with me." Similarly, the Daodejing teaches that harmony with the Tao dissolves rigid boundaries between self and cosmos: "Returning to one's roots is known as stillness. This is what is meant by returning to one's destiny."

Philosophy

Greek philosophers, such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, understood that the soul (ψυχή, psykhḗ) must have a logical faculty, the exercise of which was the most divine of human actions. At his defense trial, Socrates even summarized his teachings as nothing other than an exhortation for his fellow Athenians to excel in matters of the psyche since all bodily goods are dependent on such excellence (Apology 30a–b). Aristotle reasoned that a man's body and soul were his matter and form respectively: the body is a collection of elements and the soul is the essence. Soul or psyche (Ancient Greek: ψυχή psykhḗ, of ψύχειν psýkhein, 'to breathe', cf. Latin anima) comprises the mental abilities of a living being: reason, character, free will, feeling, consciousness, qualia, memory, perception, thinking, and so on. Depending on the philosophical system, a soul can either be mortal or immortal.

The ancient Greeks used the term "ensouled" to represent the concept of being alive, indicating that the earliest surviving Western philosophical view believed that the soul was that which gave the body life. The soul was considered the incorporeal or spiritual "breath" that animates (from the Latin anima, cf. "animal") the living organism. Francis M. Cornford quotes Pindar by saying that the soul sleeps while the limbs are active, but when one is sleeping, the soul is active and reveals "an award of joy or sorrow drawing near" in dreams. Erwin Rohde writes that an early pre-Pythagorean belief presented the soul as lifeless when it departed the body, and that it retired into Hades with no hope of returning to a body. Plato was the first thinker in antiquity to combine the various functions of the soul into one coherent conception: the soul is that which moves things (i.e., that which gives life, on the view that life is self-motion) by means of its thoughts, requiring that it be both a mover and a thinker.

Socrates and Plato

Drawing on the words of his teacher Socrates, Plato considered the psyche to be the essence of a person, being that which decides how humans behave. He considered this essence to be an incorporeal, eternal occupant of our being. Plato said that even after death, the soul exists and is able to think. He believed that as bodies die, the soul is continually reborn (metempsychosis) in subsequent bodies; however, Aristotle believed that only one part of the soul was immortal, namely the intellect (logos). The Platonic soul consists of three parts, which are located in different regions of the body:

- The logos, or logistikon (mind, nous, or reason), which is located in the head and is related to reason.

- The thymos, or thumetikon (emotion, spiritedness, or masculine), which is located near the chest region and is related to anger.

- The eros, or epithumetikon (appetitive, desire, or feminine), which is located in the stomach and is related to one's desires.

Plato compares the three parts of the soul or psyche to a societal caste system. According to Plato's theory, the three-part soul is essentially the same thing as a state's class system because, to function well, each part must contribute so that the whole functions well. Logos keeps the other functions of the soul regulated.

The soul is at the heart of Plato's philosophy. Francis Cornford described the twin pillars of Platonism as being the theory of forms on the one hand, the doctrine of the immortality of the soul on the other. Plato was the first person in the history of philosophy to believe that the soul was both the source of life and the mind. In Plato's dialogues, the soul plays many disparate roles. Among other things, Plato believes that the soul is what gives life to the body (which was articulated most of all in the Laws and Phaedrus) in terms of self-motion: to be alive is to be capable of moving yourself, and the soul is a self-mover. He also thinks that the soul is the bearer of moral properties (i.e., when one is virtuous, it is their soul that is virtuous as opposed to, say, their body). The soul is also the mind: it is that which thinks in them. This casual oscillation between different roles of the soul in observed many dialogues, including the Republic:

Is there any function of the soul that you could not accomplish with anything else, such as taking care of something (epimeleisthai), ruling, and deliberating, and other such things? Could we correctly assign these things to anything besides the soul, and say that they are characteristic (idia) of it?

No, to nothing else.

What about living? Will we deny that this is a function of the soul?

That absolutely is.

The Phaedo most famously caused problems to scholars who were trying to make sense of this aspect of Plato's theory of the soul, such as Dorothea Frede and Sarah Broadie. 2020s scholarship overturned this accusation by arguing that part of the novelty of Plato's theory of the soul is that it was the first to unite the different features and powers of the soul that became commonplace in later ancient and medieval philosophy. For Plato, the soul moves things by means of its thoughts, as one scholar puts it, and accordingly the soul is both a mover (i.e., the principle of life, where life is conceived of as self-motion) and a thinker.

Aristotle

Aristotle defined the soul, or Psūchê (ψυχή), as the "first actuality" of a naturally organized body, and argued against its separate existence from the physical body. In Aristotle's view, the primary activity, or full actualization, of a living thing constitutes its soul. For example, the full actualization of an eye, as an independent organism, is to see (its purpose or final cause). Another example is that the full actualization of a human being would be living a fully functional human life in accordance with reason (which he considered to be a faculty unique to humanity). For Aristotle, the soul is the organization of the form and matter of a natural being which allows it to strive for its full actualization. This organization between form and matter is necessary for any activity, or functionality, to be possible in a natural being. Using an artifact (non-natural being) as an example, a house is a building for human habituation but for a house to be actualized requires the material, such as wood, nails, or bricks necessary for its actuality (i.e., being a fully functional house); however, this does not imply that a house has a soul. In regards to artifacts, the source of motion that is required for their full actualization is outside of themselves (for example, a builder builds a house). In natural beings, this source of motion is contained within the being itself.

Aristotle addressed the faculties of the soul. The various faculties of the soul, such as nutrition, movement (peculiar to animals), reason (peculiar to humans), sensation (special, common, and incidental), and so forth, when exercised, constitute the "second actuality", or fulfillment, of the capacity to be alive. For example, someone who falls asleep, as opposed to someone who falls dead, can wake up and live their life, while the latter can no longer do so. Aristotle identified three hierarchical levels of natural beings: plants, animals, and people, having three different degrees of soul: Bios ('life'), Zoë ('animate life'), and Psuchë ('self-conscious life'). For these groups, he identified three corresponding levels of soul, or biological activity: the nutritive activity of growth, sustenance and reproduction which all life shares (Bios); the self-willed motive activity and sensory faculties, which only animals and people have in common (Zoë); and finally "reason", of which humans alone are capable (Pseuchë). Aristotle's discussion of the soul is in his work, De Anima (On the Soul).

Although mostly seen as opposing Plato in regard to the immortality of the soul, a controversy can be found in relation to the fifth chapter of the third book: in this text both interpretations can be argued for, soul as a whole can be deemed mortal, and a part called "active intellect" or "active mind" is immortal and eternal. Advocates exist for both sides of the controversy; it is argued that there will be permanent disagreement about its final conclusions, as no other Aristotelian text contains this specific point, and this part of De Anima is obscure. Furthermore, Aristotle states that the soul helps humans find the truth, and understanding the true purpose or role of the soul is extremely difficult.

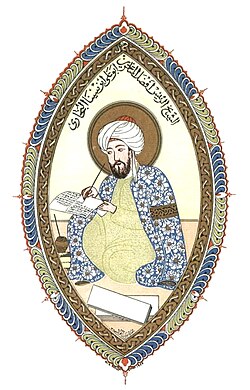

Avicenna and Ibn al-Nafis

Following Aristotle, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Ibn al-Nafis, an Arab physician, further elaborated upon the Aristotelian understanding of the soul and developed their own theories on the soul. They both made a distinction between the soul and the spirit, and the Avicennian doctrine on the nature of the soul was influential among later Muslims. Some of Avicenna's views on the soul include the idea that the immortality of the soul is a consequence of its nature, and not a purpose for it to fulfill. In his theory of "The Ten Intellects", he viewed the human soul as the tenth and final intellect.

While he was imprisoned, Avicenna wrote his famous "Floating man" thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness and the substantial nature of the soul. He told his readers to imagine themselves suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argues that in this scenario one would still have self-consciousness. He thus concludes that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms but as a primary given, a substance. This argument was later refined and simplified by René Descartes in epistemic terms, when he stated, "I can abstract from the supposition of all external things, but not from the supposition of my own consciousness."

Avicenna generally supported Aristotle's idea of the soul originating from the heart, whereas Ibn al-Nafis rejected this idea and instead argued that the soul "is related to the entirety and not to one or a few organs". He further criticized Aristotle's idea whereby every unique soul requires the existence of a unique source, in this case the heart. Al-Nafis concluded that "the soul is related primarily neither to the spirit nor to any organ, but rather to the entire matter whose temperament is prepared to receive that soul", and he defined the soul as nothing other than "what a human indicates by saying "I"".

Thomas Aquinas

Following Aristotle and Avicenna, Thomas Aquinas understood the soul to be the first actuality of the living body. Consequent to this, he distinguished three orders of life: plants, which feed and grow; animals, which add sensation to the operations of plants; and humans, which add intellect to the operations of animals. Concerning the human soul, his epistemological theory required that, since the knower becomes what he knows, the soul is definitely not corporeal—if it is corporeal when it knows what some corporeal thing is, that thing would come to be within it. Therefore, the soul has an operation which does not rely on a body organ, and therefore the soul can exist without a body. Furthermore, since the rational soul of human beings is a subsistent form and not something made of matter and form, it cannot be destroyed in any natural process.

The full argument for the immortality of the soul and Aquinas' elaboration of Aristotelian theory is found in the Summa Theologica. Aquinas affirmed in the doctrine of the divine effusion of the soul, the particular judgement of the soul after the separation from a dead body, and the final resurrection of the flesh. He recalled two canons of the 4th century, for which "the rational soul is not engendered by coition", and "is one and the same soul in man, that both gives life to the body by being united to it, and orders itself by its own reasoning". Moreover, he believed in a unique and tripartite soul, within which are distinctively present a nutritive, a sensitive, and intellectual soul. The latter is created by God and is taken solely by human beings, includes the other two types of soul and makes the sensitive soul incorruptible.

According to Thomas Aquinas, the soul is tota in toto corpore. This means that the soul is entirely contained in every single part of the human body, and, therefore, ubiquitous and cannot be placed in a single organ, such as the heart or brain, nor is it separable from the body (except after the body's death). In the fourth book of De Trinitate, Augustine of Hippo states that the soul is all in the whole body and all in any part of it.

Immanuel Kant

In his discussions of rational psychology, Immanuel Kant identified the soul as the "I" in the strictest sense, and argued that the existence of inner experience can neither be proved nor disproved. He said, "We cannot prove a priori the immateriality of the soul, but rather only so much: that all properties and actions of the soul cannot be recognized from materiality." It is from the "I", or soul, that Kant proposes transcendental rationalization but cautions that such rationalization can only determine the limits of knowledge if it is to remain practical.

Kant critiques the metaphysics of the soul—an investigation he calls "rational psychology"—in the Paralogisms of Pure Reason. Rational psychology, as he defines it, seeks to establish metaphysical claims about the soul’s nature by analyzing the proposition "I think". Many of Kant’s rationalist predecessors and contemporaries believed that reflecting on the "I" in "I think" could demonstrate that the self is necessarily a substance (implying the soul’s existence), indivisible (to argue for the soul’s immortality), self-identical (pertaining to personal identity), and separate from the external world (leading to skepticism about external reality). Kant, however, asserts that such conclusions stem from an error of reasoning.

Kant believes this error arises when the conceptual thought of the "I" in "I think" is conflated with genuine cognition of the "I" as an object. Cognition, for Kant, requires both intuition (sensory experience) and concepts, whereas the "I" here involves only abstract conceptual thought. For example, consider whether the self can be known as a substance. While the "I" is always the subject of thoughts (never a predicate of something else), recognizing something as a substance also requires intuiting it as a persistent object. Since a person lacks any intuition of the "I" itself, they cannot cognize it as a substance. Thus, in Kant's view, although a person will inevitably conceive of the "I" as a soul-like substance, true knowledge of the soul’s existence or nature remains out of their reach.

Contemporary philosophy

The notion of soul often relies on a theory called mind-body dualism, which posits that mental phenomena are non-physical. If body and soul (or mind) are of two distinct realms, the question remains how these two are related. Contemporary philosophy of mind distinguishes three major dualist theories about the relationship between mental properties and the body: interactionism, parallelism, and epiphenomenalism.

Interactionism holds that physical events and mental events interact with each other. This view is often considered to be the most intuitive: one perceives the mind reacting upon physical stimulation and then thoughts and feelings act upon the physical body, such as by moving it. Thus, humans are naturally inclined in favor of interactionism. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy states, "[t]he critical feature of interactionism is its commitment to 'two-way' causation – mental-to-physical causation and physical-to-mental causation."

Parallelism sidesteps debates about mind-body interaction by proposing that both operate in parallel. Under this framework, mental and physical events do not causally influence one another; they merely coincide. When causation occurs, it is strictly confined within each domain: mental events only trigger or result from other mental events, and physical events exclusively cause or are caused by other physical events.

Epiphenomenalism posits that physical events generate mental events, but mental events themselves lack causal power—they cannot influence physical events or even other mental phenomena. This stance partially accommodates interactionism by permitting causation in a single direction (physical to mental), thereby rejecting parallelism, which denies any causal link between the two realms. In this framework, the mind is likened to a bodily shadow: while the body actively produces effects, the mind is merely a passive byproduct, incapable of driving outcomes or interactions.

Non-dualist theories include physicalism, the view that everything is physical, and idealism, the conviction that a priori intelligence grounds all phenomena (science). George Howison put the question about (the necessity of logically prior) souls in context thus:

The question whether we have not some knowledge independent of any and all experience – whether there must not, unavoidably, be some knowledge a priori, some knowledge which we come at simply by virtue of our nature – is really the paramount question, around which the whole conflict in philosophy concentrates, and on the decision of which the settlement of every other question hangs.

Psychology

"Seelenglaube" or "soul-belief" is a prominent feature in Otto Rank's work. Rank explains the importance of immortality in the psychology of primitive, classical and modern interest in life and death. Rank's work directly opposed the scientific psychology that concedes the possibility of the soul's existence and postulates it as an object of research without really admitting that it exists. He says, "Just as religion represents a psychological commentary on the social evolution of man, various psychologies represent our current attitudes toward spritual belief. In the animistic era, psychologizing was a creating of the soul; in the religious era, it was a representing of the soul to one's self; in our era of natural science it is a knowing of the individual soul." Rank's work had a significant influence on Ernest Becker's understanding of a universal interest in immortality. In The Denial of Death, Becker describes "soul" in terms of Søren Kierkegaard use of "self":

Kierkegaard's use of "self" may be a bit confusing. He uses it to include the symbolic self and the physical body. It is a synonym really for "total personality" that goes beyond the person to include what we would now call the "soul" or the "ground of being" out of which the created person sprang.

According to Cognitive scientist Jesse Bering and psychologist Nicholas Humphrey, humans are initially inclined to believe in a soul and are born as soul-body dualists. As such, religious institutions did not need to invent or inherent the idea of the soul from previous traditions, rather the concept has always been present throughout human history. Echoing that sentiment, American philosopher Steward Goetz has claimed that according to anthropologists and psychologists, ordinary human beings are soul-body substance dualists, who, at all times and in all places, have believed in the existence of a distinction between the soul and the body.

Parapsychology

Some parapsychologists attempted to establish, by scientific experiment, whether a soul separate from the brain exists, as is more commonly defined in religion rather than as a synonym of psyche or mind.

One such attempt became known as the "21 grams experiment". In 1901, Duncan MacDougall, a physician from Haverhill, Massachusetts, who wished to scientifically determine if a soul had weight, identified six patients in nursing homes whose deaths were imminent. Four were suffering from tuberculosis, one from diabetes, and one from unspecified causes. MacDougall specifically chose people who were suffering from conditions that caused physical exhaustion, as he needed the patients to remain still when they died to measure them accurately. When the patients looked like they were close to death, their entire bed was placed on an industrial sized scale that was sensitive within two tenths of an ounce (5.6 grams). One of the patients lost "three-fourths of an ounce" (21.3 grams), coinciding with the time of death, which led MacDougall to the conclusion that the soul had weight.

The physicist Robert L. Park wrote that MacDougall's experiments "are not regarded today as having any scientific merit", and the psychologist Bruce Hood wrote that "because the weight loss was not reliable or replicable, his findings were unscientific".