First edition cover | |

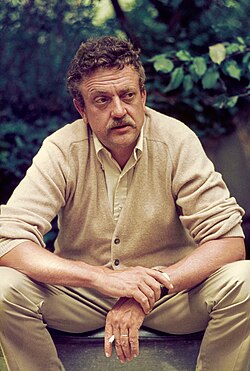

| Author | Kurt Vonnegut |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dark comedy Satire Science fiction War novel Metafiction Postmodernism |

| Publisher | Delacorte |

Publication date | March 31, 1969 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 190 (First Edition) |

| ISBN | 0-385-31208-3 (first edition, hardback) |

| OCLC | 29960763 |

| 813.54 | |

| LC Class | PS3572.O5 S6 1994 |

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut. It follows the life experiences of Billy Pilgrim, from his early years, to his time as an American soldier and chaplain's assistant during World War II, to the post-war years. Throughout the novel, Billy frequently travels back and forth through time. The protagonist deals with a temporal crisis as a result of his post-war psychological trauma. The text centers on Billy's capture by the German Army and his survival of the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience that Vonnegut endured as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of "unmatched moral clarity" and "one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time".

Plot

The novel's first chapter begins with "All this happened, more or less"; this introduction implies that an unreliable narrator tells the story. Vonnegut utilizes a non-linear, non-chronological description of events to reflect Billy Pilgrim's psychological state. Events become clear through flashbacks and descriptions of time travel experiences. In the first chapter, the narrator describes his writing of the book, his experiences as a University of Chicago anthropology student and a Chicago City News Bureau correspondent, his research on the Children's Crusade and the history of Dresden, and his visit to Cold War–era Europe with his wartime friend Bernard V. O'Hare. In the second chapter, Vonnegut introduces Billy Pilgrim, an American man from the fictional town of Ilium, New York. Billy believes that an extraterrestrial species from the planet Tralfamadore held him captive in an alien zoo and that he has experienced time travel.

As a chaplain's assistant in the United States Army during World War II, Billy is an ill-trained, disoriented and fatalistic American soldier who discovers that he does not like war and refuses to fight. He is transferred from a base in South Carolina to the front line in Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge. He narrowly escapes death as the result of a string of events. He also meets Roland Weary, a patriot, warmonger, and sadistic bully who derides Billy's cowardice. The two of them are captured in 1944 by the Germans, who confiscate all of Weary's belongings and force him to wear wooden clogs that cut painfully into his feet; the resulting wounds become gangrenous, which eventually kills him. While Weary is dying in a rail car full of prisoners, he convinces a fellow soldier, Paul Lazzaro, that Billy is to blame for his death. Lazzaro vows to avenge Weary's death by killing Billy, because revenge is "the sweetest thing in life."

At this exact time, Billy becomes "unstuck in time"; Billy travels through time to moments from his past and future. The novel describes the transportation of Billy and the other prisoners into Germany. The German soldiers held their prisoners in the German city of Dresden; the prisoners had to work in "contract labor" (forced labor); these events occurred in 1945. The Germans detained Billy and his fellow prisoners in an empty slaughterhouse called Schlachthof-fünf ("slaughterhouse five"). During the Allied bombing of Dresden, German guards hid their captives in the partially underground setting of the slaughterhouse; this protected those captives from complete annihilation. As a result, they are among the few survivors of the firestorm that raged in the city between February 13 and 15, 1945. After V-E Day in May 1945, Billy was transferred to the United States and received an honorable discharge in July 1945.

Billy is hospitalized with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder and placed under psychiatric care at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Lake Placid. During Billy's stay at the hospital, Eliot Rosewater introduces him to the work of an obscure science fiction writer named Kilgore Trout. After his release, Billy marries Valencia Merble, whose father owns the Ilium School of Optometry that Billy later attends. Billy becomes a successful and wealthy optometrist. In 1947, Billy and Valencia conceive their first child, Robert, on their honeymoon in Cape Ann, Massachusetts. Two years later, their second child, Barbara, was born. On Barbara's wedding night, Billy is abducted by a flying saucer and taken to a planet many light-years away from Earth called Tralfamadore. The Tralfamadorians have the power to see in four dimensions; they simultaneously observe all points in the space-time continuum. They universally adopt a fatalistic worldview: death means nothing to them, and their typical response to hearing about death is "so it goes."

The Tralfamadorians transport Billy to Tralfamadore and place him inside a transparent geodesic dome exhibit in a zoo; the inside resembles a house on planet Earth. The Tralfamadorians later abduct a pornographic film star named Montana Wildhack, who had disappeared on Earth and supposedly drowned in San Pedro Bay. The Tralfamadorians intend to have her mate with Billy. Montana and Billy fall in love and have a child together. Billy is instantaneously sent back to Earth in a time warp to re-live past or future moments of his life.

In 1968, Billy and a co-pilot are the only survivors of a plane crash in Vermont. While driving to visit Billy in the hospital, Valencia crashes her car and dies of carbon monoxide poisoning. Billy shares a hospital room with Bertram Rumfoord, a Harvard University history professor researching an official war history of the USAAF in World War II. They discuss the bombing of Dresden, which the professor initially refuses to believe Billy witnessed. Despite the significant loss of civilian life and the destruction of Dresden, they both regard the bombing as a justifiable act.

Billy's daughter takes him home to Ilium. He escapes and flees to New York City. In Times Square he visits a pornographic book store, where he discovers books written by Kilgore Trout and reads them. He discovers a science fiction novel titled The Big Board at the bookstore. The novel is about a couple abducted by extraterrestrials. The aliens trick the abductees into thinking they are managing investments on Earth, which excites the humans and, in turn, sparks interest in the observers. He also finds some magazine covers that mention Montana Wildhack's disappearance. While Billy surveys the bookstore, one of Montana's pornographic films plays in the background. Later in the evening, when he discusses his time travels to Tralfamadore on a radio talk show, he is ejected from the studio. He returns to his hotel room, falls asleep, and time-travels back to 1945 in Dresden. Billy and his fellow prisoners are tasked with locating and burying the dead. After a Maori New Zealand soldier working with Billy dies of dry heaves the Germans begin cremating the bodies en masse with flamethrowers. German soldiers execute Billy's friend Edgar Derby for stealing a teapot. Eventually all of the German soldiers leave to fight on the Eastern Front, leaving Billy and the other prisoners alone with tweeting birds as the war ends.

Through non-chronological storytelling, other parts of Billy's life are told throughout the book. After Billy is evicted from the radio studio, Barbara treats Billy as a child and often monitors him. Robert becomes starkly anti-communist, enlists as a Green Beret and fights in the Vietnam War. Billy is eventually killed in 1976, at which point the United States has been partitioned into twenty countries and attacked by China with thermonuclear weapons. He gives a speech in a baseball stadium in Chicago in which he predicts his own death and proclaims that "if you think death is a terrible thing, then you have not understood a word I've said." Billy soon after is shot with a laser gun by an assassin commissioned by the elderly Lazzaro.

Characters

- Narrator: Recurring as a minor character, the narrator seems anonymous while also clearly identifying himself as Kurt Vonnegut, when he says, "That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book." As noted above, as an American soldier during World War II, Vonnegut was captured by Germans at the Battle of the Bulge and transported to Dresden. He and fellow prisoners-of-war survived the bombing while being held in a deep cellar of Schlachthof Fünf ("Slaughterhouse-Five"). The narrator begins the story by describing his connection to the firebombing of Dresden and his reasons for writing Slaughterhouse-Five.

- Billy Pilgrim: A fatalistic optometrist ensconced in a dull, safe marriage in Ilium, New York. During World War II, he was held as a prisoner-of-war in Dresden and survived the firebombing, experiences which had a lasting effect on his post-war life. His time travel occurs at desperate times in his life; he relives past and future events and becomes fatalistic (though not a defeatist) because he claims to have seen when, how and why he will die.

- Roland Weary: A weak man dreaming of grandeur and obsessed with gore and vengeance, who saves Billy several times (despite Billy's protests) in hopes of attaining military glory. He coped with his unpopularity in his home city of Pittsburgh by befriending and then beating people less well-liked than him, and is obsessed with his father's collection of torture equipment. Weary is also a bully who beats Billy and gets them both captured, leading to the loss of his winter uniforms and boots. Weary dies of gangrene on the train en route to the POW camp, and blames Billy in his dying words.

- Paul Lazzaro: Another POW. A sickly, ill-tempered car thief from Cicero, Illinois who takes Weary's dying words as a revenge commission to kill Billy. He keeps a mental list of his enemies, claiming he can have anyone "killed for a thousand dollars plus traveling expenses." Lazzaro eventually fulfills his promise to Weary and has Billy assassinated by a laser gun in 1976.

- Kilgore Trout: A failed science fiction writer whose hometown is also Ilium, New York, and who makes money by managing newspaper delivery boys. He has received only one fan letter (from Eliot Rosewater; see below). After Billy meets him in a back alley in Ilium, he invites Trout to his wedding anniversary celebration. There, Kilgore follows Billy, thinking the latter has seen through a "time window." Kilgore Trout is also a main character in Vonnegut's 1973 novel Breakfast of Champions.

- Edgar Derby: A middle-aged high school teacher who felt that he needed to participate in the war rather than just send off his students to fight. One of his sons is serving with the marines in the Pacific Theatre. Though relatively unimportant, Derby seems to be the only American before the bombing of Dresden to understand what war can do to people. During Campbell's presentation he stands up and castigates him, defending American democracy and the alliance with the Soviet Union. German forces summarily execute him for looting after they catch him taking a teapot from catacombs after the bombing. The undamaged teapot is identical to one he has at home, and it is his astonishment at the find amongst the rubble, that gives him away to the guards. Vonnegut has said that this death is the climax of the book as a whole.

- Howard W. Campbell Jr.: An American-born Nazi. Before the war, he lived in Germany where he was a noted German-language playwright recruited by the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda. In an essay, he connects the misery of American poverty to the disheveled appearance and behavior of the American POWs. Edgar Derby confronts him when Campbell tries to recruit American POWs into the American Free Corps to fight the Communist Soviet Union on behalf of the Nazis. He appears wearing swastika-adorned cowboy hat and boots and with a red, white and blue Nazi armband. Campbell is the protagonist of Vonnegut's 1962 novel Mother Night.

- Valencia Merble: Billy's wife and the mother of their children, Robert and Barbara. Billy is emotionally distant from her. She dies from carbon monoxide poisoning after an automobile accident en route to the hospital to see Billy after his airplane crash.

- Robert Pilgrim: Son of Billy and Valencia. A troubled, middle-class boy and disappointing son who becomes an alcoholic at age 16, drops out of high school, and is arrested for vandalizing a Catholic cemetery. He later so absorbs the anti-Communist worldview that he metamorphoses from suburban adolescent rebel to Green Beret sergeant. He wins a Purple Heart, Bronze Star and Silver Star in the Vietnam War.

- Barbara Pilgrim: Daughter of Billy and Valencia. She is a "bitchy flibbertigibbet" from having had to assume the family's leadership at the age of twenty. She has "legs like an Edwardian grand piano," marries an optometrist, and treats her widowed father as a childish invalid.

- Tralfamadorians: The race of extraterrestrial beings who appear (to humans) like upright toilet plungers with a hand atop, in which is set a single green eye. They abduct Billy and teach him about time's relation to the world (as a fourth dimension), fate, and the nature of death. The Tralfamadorians are featured in several Vonnegut novels. In Slaughterhouse Five, they reveal that the universe will be accidentally destroyed by one of their test pilots, and there is nothing they can do about it.

- Montana Wildhack: A beautiful young model who is abducted and placed alongside Billy in the zoo on Tralfamadore. She and Billy develop an intimate relationship and they have a child. She apparently remains on Tralfamadore with the child after Billy is sent back to Earth. Billy sees her in a film showing in a pornographic book store when he stops to look at the Kilgore Trout novels sitting in the window. Her unexplained disappearance is featured on the covers of magazines sold in the store.

- "Wild Bob": A superannuated army officer Billy meets in the war. He tells his fellow POWs to call him "Wild Bob", as he thinks they are the 451st Infantry Regiment and under his command. He explains "If you're ever in Cody, Wyoming, ask for Wild Bob", which is a phrase that Billy repeats to himself throughout the novel. He dies of pneumonia.

- Eliot Rosewater: Billy befriends him in the veterans' hospital; he introduces Billy to the sci-fi novels of Kilgore Trout. Rosewater wrote the only fan letter Trout ever received. Rosewater had also suffered a terrible event during the war. Billy and Rosewater find the Trout novels helpful in dealing with the trauma of war. Rosewater is featured in other Vonnegut novels, such as God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965).

- Bertram Copeland Rumfoord: A Harvard history professor, retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general, and millionaire. He shares a hospital room with Billy and is interested in the Dresden bombing. He is in the hospital after breaking his leg on his honeymoon with his fifth wife Lily, a barely literate high school drop-out and go-go girl. He is described as similar in appearance and mannerisms to Theodore Roosevelt. Bertram is likely a relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, a character in Vonnegut's 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan.

- The Scouts: Two American infantry scouts trapped behind German lines who find Roland Weary and Billy. Roland refers to himself and the scouts as the "Three Musketeers". The scouts abandon Roland and Billy because the latter are slowing them down. They are revealed to have been shot and killed by Germans in ambush.

- Bernard V. O'Hare: The narrator's old war friend who was also held in Dresden and accompanies him there after the war. He is the husband of Mary O'Hare, and is a district attorney from Pennsylvania.

- Mary O'Hare: The wife of Bernard V. O'Hare, to whom Vonnegut promised to name the book The Children's Crusade. She is briefly discussed in the beginning of the book. When the narrator and Bernard try to recollect their war experiences Mary complains that they were just "babies" during the war and that the narrator will portray them as valorous men. The narrator befriends Mary by promising that he will portray them as she said and that in his book "there won't be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne."

- Werner Gluck: The sixteen-year-old German charged with guarding Billy and Edgar Derby when they are first placed at Slaughterhouse Five in Dresden. He does not know his way around and accidentally leads Billy and Edgar into a communal shower where some German refugee girls from Breslau are bathing. He is described as appearing similar to Billy.

Style

In keeping with Vonnegut's signature style, the novel's syntax and sentence structure are simple, and irony, sentimentality, black humor, and didacticism are prevalent throughout the work. Like much of his oeuvre, Slaughterhouse-Five is broken into small pieces, and in this case, into brief experiences, each focused on a specific point in time. Vonnegut has noted that his books "are essentially mosaics made up of a whole bunch of tiny little chips...and each chip is a joke." Vonnegut also includes hand-drawn illustrations in Slaughterhouse-Five, and also in his next novel, Breakfast of Champions (1973). Characteristically, Vonnegut makes heavy use of repetition, frequently using the phrase, "So it goes". He uses it as a refrain when events of death, dying, and mortality occur or are mentioned; as a narrative transition to another subject; as a memento mori; as comic relief; and to explain the unexplained. The phrase appears 106 times.

The book has been categorized as a postmodern, meta-fictional novel. The first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five is written in the style of an author's preface about how he came to write the novel. The narrator introduces the novel's genesis by telling of his connection to the Dresden bombing, and why he is recording it. He provides a description of himself and of the book, saying that it is a desperate attempt at creating a scholarly work. He ends the first chapter by discussing the beginning and end of the novel. He then segues to the story of Billy Pilgrim: "Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time", thus the transition from the writer's perspective to that of the third-person, omniscient narrator. (The use of "Listen" as an opening interjection has been said to mimic the opening "Hwaet!" of the medieval epic poem Beowulf.) The fictional "story" appears to begin in Chapter Two, although there is no reason to presume that the first chapter is not also fiction. This technique is common in postmodern meta-fiction.

The narrator explains that Billy Pilgrim experiences his life discontinuously, so that he randomly lives (and re-lives) his birth, youth, old age and death, rather than experiencing them in the normal linear order. There are two main narrative threads: a description of Billy's World War II experience, which, though interrupted by episodes from other periods and places in his life, is mostly linear; and a description of his discontinuous pre-war and post-war lives. A main idea is that Billy's existential perspective had been compromised by his having witnessed Dresden's destruction (although he had come "unstuck in time" before arriving in Dresden). Slaughterhouse-Five is told in short, declarative sentences, which create the impression that one is reading a factual report.

The first sentence says, "All this happened, more or less." (In 2010, the line was ranked No. 38 on the American Book Review's list of "100 Best First Lines from Novels".) The opening sentences of the novel have been said to contain the aesthetic "method statement" of the entire novel.

Themes

War and death

In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut attempts to come to terms with war through the narrator's eyes, Billy Pilgrim. An example within the novel, showing Vonnegut's aim to accept his past war experiences, occurs in chapter one, when he states that "All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn't his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I've changed all the names." As the novel continues, it is relevant that the reality is death.

Slaughterhouse-Five focuses on human imagination while interrogating the novel's overall theme, which is the catastrophic impact that war leaves behind. Death is something that happens fairly often in Slaughterhouse-Five. When a death occurs in the novel, Vonnegut marks the occasion with the saying "so it goes." Bergenholtz and Clark write about what Vonnegut actually means when he uses that saying: "Presumably, readers who have not embraced Tralfamadorian determinism will be both amused and disturbed by this indiscriminate use of 'So it goes.' Such humor is, of course, black humor."

Religion and philosophy

Christian philosophy

Christian philosophy is present in Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, though not generally in a well-regarded manner. When God and Christianity is brought up in the work, it is often mentioned in a bitter or disregarding tone, particularly with regard to how the soldiers react to the mention of it. Though Billy Pilgrim had adopted some part of Christianity, he did not ascribe to all of it. JC Justus summarizes it the best when he mentions that, "'Tralfamadorian determinism and passivity' that Pilgrim later adopts as well as Christian fatalism wherein God himself has ordained the atrocities of war...". Following Justus's argument, Pilgrim was a character that had been through war and traveled through time. Having experienced all of these horrors in his lifetime, Pilgrim ended up adopting the Christian ideal that God had everything planned and he had given his approval for the war to happen.

Tralfamadorian philosophy

As Billy Pilgrim becomes "unstuck in time", he is faced with a new type of philosophy. Upon making acquaintance with the Tralfamadorians, he learns a different viewpoint concerning fate and free will. While Christianity may state that fate and free will are matters of God's divine choice and human interaction, Tralfamadorianism would disagree. According to Tralfamadorian philosophy, things are and always will be, and there is nothing that can change them. When Billy asks why they had chosen him, the Tralfamadorians reply, "Why you? Why us for that matter? Why anything? Because this moment simply is." The mindset of the Tralfamadorian is not one in which free will exists. Things happen because they were always destined to be happening. The narrator of the story explains that the Tralfamadorians see time all at once. This concept of time is best explained by the Tralfamadorians themselves, as they speak to Billy Pilgrim on the matter stating, "I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is." After this particular conversation on seeing time, Billy makes the statement that this philosophy does not seem to evoke any sense of free will. To this, the Tralfamadorian reply that free will is a concept that, out of the "visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe" and "studied reports on one hundred more," "only on Earth is there any talk of free will."

Using the Tralfamadorian passivity of fate, Pilgrim learns to overlook death and the shock involved with death. He claims the Tralfamadorian philosophy on death to be his most important lesson:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. ... When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is "So it goes."

Postmodernism

The significance of postmodernism is a reoccurring theme in Vonnegut's works. Postmodernism arose as a rejection of modernist narratives and structures. According to one critic, Tralfamadorianism is a restatement of Christian teleology: There is no purpose to life, effects do not have causes; the only reason for anything is that God has ordained it. This juxtaposition is displayed throughout the book, rather directly asking the reader to confront the logical absurdities inherent in both Christian faith and Tralfamadorianism. The rigid and dogmatic approach of Christianity is dismissed, while determinism is critiqued.

Mental illness

Some have argued that Vonnegut is speaking out for veterans, many of whose post-war states are untreatable. Pilgrim's symptoms have been identified as what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder, which didn't exist as a term when the novel was written. In the words of one writer, "perhaps due to the fact that PTSD was not officially recognized as a mental disorder yet, the establishment fails Billy by neither providing an accurate diagnosis nor proposing any coping mechanisms." Billy found life meaningless due to his experiences in the war, which desensitized and forever changed him.

Symbols

Dresden

Vonnegut was in the city of Dresden when it was bombed; he came home traumatized and unable to properly communicate the horror of what happened there. Slaughterhouse-Five is the product of the twenty years of work it took for him to articulate the experience in a way that satisfied him. William Allen says, "Precisely because the story was so hard to tell, and because Vonnegut was willing to take two decades necessary to tell it – to speak the unspeakable – Slaughterhouse-Five is a great novel, a masterpiece sure to remain a permanent part of American literature."

Food

Billy Pilgrim ended up owning "half of three Tastee-Freeze stands. Tastee-Freeze was a sort of frozen custard. It gave all the pleasure that ice cream could give, without the stiffness and bitter coldness of ice cream" (61). Throughout Slaughterhouse-Five, when Billy is eating or near food, he thinks of food in positive terms. This is partly because food is both a status symbol and comforting to people in Billy's situation. "Food may provide nourishment, but its more important function is to soothe ... Finally, food also functions as a status symbol, a sign of wealth. For instance, en route to the German prisoner-of-war camp, Billy gets a glimpse of the guards' boxcar and is impressed by its contents ... In sharp contrast, the Americans' boxcar proclaims their dependent prisoner-of-war status."

The Bird

Throughout the novel, the bird sings "Poo-tee-weet?" After the Dresden firebombing, the bird breaks out in song. The bird also sings outside of Billy's hospital window. The song has been interpreted as symbolizing a loss of words, or the inadequacy of words to describe traumatic situations.

Allusions and references

Allusions to other works

As in other novels by Vonnegut, certain characters cross over from other stories, making cameo appearances and connecting the discrete novels to a greater opus. Fictional novelist Kilgore Trout, often an important character in other Vonnegut novels, is a social commentator and a friend to Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse-Five. In one case, he is the only non-optometrist at a party; therefore, he is the odd man out. He ridicules everything the Ideal American Family holds true, such as Heaven, Hell, and Sin. In Trout's opinion, people do not know if the things they do turn out to be good or bad, and if they turn out to be bad, they go to Hell, where "the burning never stops hurting." Other crossover characters are Eliot Rosewater, from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; Howard W. Campbell Jr., from Mother Night; and Bertram Copeland Rumfoord, relative of Winston Niles Rumfoord, from The Sirens of Titan. While Vonnegut re-uses characters, the characters are frequently rebooted and do not necessarily maintain the same biographical details from appearance to appearance. Trout in particular is palpably a different person (although with distinct, consistent character traits) in each of his appearances in Vonnegut's work.

In the Twayne's United States Authors series volume on Kurt Vonnegut, about the protagonist's name, Stanley Schatt says:

By naming the unheroic hero Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut contrasts John Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress" with Billy's story. As Wilfrid Sheed has pointed out, Billy's solution to the problems of the modern world is to "invent a heaven, out of 20th century materials, where Good Technology triumphs over Bad Technology. His scripture is Science Fiction, Man's last, good fantasy".

The city in which the novel is set, Ilium, New York, is another allusion. This city appears in many of his books.

Cultural and historical allusions

Slaughterhouse-Five makes numerous cultural, historical, geographical, and philosophical allusions. It tells of the bombing of Dresden in World War II, and refers to the Battle of the Bulge, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights protests in American cities during the 1960s. Billy's wife, Valencia, has a "Reagan for President!" bumper sticker on her Cadillac, referring to Ronald Reagan's failed 1968 Republican presidential nomination campaign. Another bumper sticker is mentioned, reading "Impeach Earl Warren," referencing a real-life campaign by the far-right John Birch Society.

The Serenity Prayer appears twice. Critic Tony Tanner suggested that it is employed to illustrate the contrast between Billy Pilgrim's and the Tralfamadorians' views of fatalism. Richard Hinchcliffe contends that Billy Pilgrim could be seen at first as typifying the Protestant work ethic, but he ultimately converts to evangelicalism.

Vonnegut's own experiences

In 1995, Vonnegut said that Billy Pilgrim was modeled on Edward "Joe" Crone, a thin soldier who died in Dresden. Vonnegut had told this to friends earlier, but waited until after he learned that both of Crone's parents were deceased to publicly disclose this information.

Edgar Derby, killed for looting a teapot, was modeled on Vonnegut's fellow prisoner Mike Palaia, who was executed for plundering a jar of food (variously described as beans, fruit, or cherries).

Reception

The reviews of Slaughterhouse-Five have been largely positive since the March 31, 1969 review in the New York Times stated: "you'll either love it, or push it back in the science-fiction corner." It was Vonnegut's first novel to become a bestseller, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for sixteen weeks and peaking at No. 4. In 1970, Slaughterhouse-Five was nominated for best-novel Nebula and Hugo Awards. It lost both to The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. It has since been widely regarded as a classic anti-war novel, and has appeared in Time magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.

Censorship controversy

Slaughterhouse-Five has been the subject of many attempts at censorship due to its irreverent tone, purportedly obscene content and depictions of sex, American soldiers' use of profanity, and perceived heresy. It was one of the first literary acknowledgments that homosexual men, referred to in the novel as "fairies", were among the victims of the Holocaust.

In the United States it has at times been banned from literature classes, removed from school libraries, and struck from literary curricula. In 1972, following the ruling of Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, it was banned from Rochester Community Schools in Oakland County, Michigan. The circuit judge described the book as "depraved, immoral, psychotic, vulgar and anti-Christian." It was later reinstated.

In 1973, Vonnegut learned of a school district in North Dakota that was antagonistic towards Slaughterhouse-Five. An English teacher at a high school in the district wanted to read the novel with their class. Charles McCarthy, the head of the school board, declared the novel inappropriate because of obscene language. All copies of Vonnegut's novel in the school were burned in a furnace.

In a letter to McCarthy in 1973, Vonnegut defended his credibility, his character, and his work. In the letter, entitled "I Am Very Real", Vonnegut wrote that his books "beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are". He contended that his work should not be censored based on the general message in the novel.

The U.S. Supreme Court considered the First Amendment implications of the removal of the book, among others, from public school libraries in the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982) and concluded that "local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to 'prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.'" Slaughterhouse-Five is the sixty-seventh entry to the American Library Association's list of the "Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999" and number forty-six on the ALA's "Most Frequently Challenged Books of 2000–2009". In August 2011, the novel was banned at the Republic High School in Missouri. The Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library countered by offering 150 free copies of the novel to Republic High School students on a first-come, first-served basis.

In an effort to comply with a new 2024 Tennessee state law which added to the 2022 Age Appropriate Materials Act, Slaughterhouse-Five was banned - along with nearly 400 other titles - at the discretion of middle and high school librarians serving Wilson County Schools, a public school district in the greater metropolitan Nashville area. It has also been recently banned from school libraries in the state of Florida.

In 2024 the book was banned in Texas by the Katy Independent School District on the basis that the novel is "adopting, supporting, or promoting gender fluidity" despite also pronouncing a bullying policy that protects infringements on the rights of the student.

Criticism

On the book's philosophy

Slaughterhouse-Five has been described as a quietist work, because Billy Pilgrim believes that the notion of free will is a quaint Earthling illusion. According to Robert Merrill and Peter A. Scholl, "Vonnegut's critics seem to think that he is saying the same thing [as the Tralfamadorians]." For Anthony Burgess, "Slaughterhouse is a kind of evasion—in a sense, like J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan—in which we're being told to carry the horror of the Dresden bombing, and everything it implies, up to a level of fantasy..." For Charles Harris, "The main idea emerging from Slaughterhouse-Five seems to be that the proper response to life is one of resigned acceptance." For Alfred Kazin, "Vonnegut deprecates any attempt to see tragedy, that day, in Dresden...He likes to say, with arch fatalism, citing one horror after another, 'So it goes.'" For Tanner, "Vonnegut has...total sympathy with such quietistic impulses." The same notion is found throughout The Vonnegut Statement, a book of original essays written and collected by Vonnegut's most loyal academic fans. When confronted with the question of how the desire to improve the world fits with the notion of time presented in Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut responded "you understand, of course, that everything I say is horseshit."

Historical inaccuracy

For certain elements of historical research, Vonnegut used (and quoted) The Destruction of Dresden, a book published in 1963 by British author David Irving. Irving was later denounced and discredited for being a Holocaust denier and a Nazi sympathizer. In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut quotes and bases claims on Irving's book, most notably that 135,000 people were killed in the bombing of Dresden. New, evidence-based research (published a year after Vonnegut's death) has found that Irving's claims are inaccurate, and the number of deaths in the Dresden bombing was fewer than 25,000. George Packer, in an essay published in The New Yorker, claimed that "For many readers of Irving and Vonnegut, the bombing of Dresden scrambled the order of perpetrators and victims in the Second World War and came close to establishing a moral equivalence", referring to the exaggeration that "reached the West through 'The Destruction of Dresden', a 1963 best-seller by David Irving".

Both before and for years after Vonnegut's book was initially published, the figure of 135,000 was used even by American officials, including U.S Air Force general Ira C. Eaker, who was quoted in Slaughterhouse-Five. Later editions of Slaughterhouse-Five have not featured any kind of explanatory note about, or correction to, this figure.