| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bose–Einstein statistics |

| Family | Gauge boson |

| Interactions | Electromagnetic, gravity |

| Symbol | γ |

| Theorized | Albert Einstein (1905) The name "photon" is generally attributed to Gilbert N. Lewis (1926) |

| Mass | 0 (theoretical value) < 1×10−18 eV/c2(experimental limit) |

| Mean lifetime | Stable |

| Electric charge | 0

< 1×10−35 e(experimental limit) |

| Color charge | No |

| Spin | 1 ħ |

| Spin states | +1 ħ, −1 ħ |

| Parity | −1 |

| C parity | −1 |

| Condensed | I(J PC) = 0, 1 (1−−) |

A photon (from Ancient Greek φῶς, φωτός (phôs, phōtós) 'light') is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can only move at one speed, the speed of light measured in vacuum. The photon belongs to the class of boson particles.

As with other elementary particles, photons are best explained by quantum mechanics and exhibit wave–particle duality, their behavior featuring properties of both waves and particles. The modern photon concept originated during the first two decades of the 20th century with the work of Albert Einstein, who built upon the research of Max Planck. While Planck was trying to explain how matter and electromagnetic radiation could be in thermal equilibrium with one another, he proposed that the energy stored within a material object should be regarded as composed of an integer number of discrete, equal-sized parts. To explain the photoelectric effect, Einstein introduced the idea that light itself is made of discrete units of energy. In 1926, Gilbert N. Lewis popularized the term photon for these energy units. Subsequently, many other experiments validated Einstein's approach.

In the Standard Model of particle physics, photons and other elementary particles are described as a necessary consequence of physical laws having a certain symmetry at every point in spacetime. The intrinsic properties of particles, such as charge, mass, and spin, are determined by gauge symmetry. The photon concept has led to momentous advances in experimental and theoretical physics, including lasers, Bose–Einstein condensation, quantum field theory, and the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics. It has been applied to photochemistry, high-resolution microscopy, and measurements of molecular distances. Moreover, photons have been studied as elements of quantum computers, and for applications in optical imaging and optical communication such as quantum cryptography.

Physical properties

The photon has no electric charge, is generally considered to have zero rest mass, and is a stable particle. The experimental upper limit on the photon mass is very small, on the order of 10−53 g; its lifetime would be more than 1018 years. For comparison, the age of the universe is about 1.38×1010 years.

In a vacuum, a photon has two possible polarization states. The photon is the gauge boson for electromagnetism, and therefore all other quantum numbers of the photon (such as lepton number, baryon number, and flavour quantum numbers) are zero. Also, photons obey Bose–Einstein statistics, and not Fermi–Dirac statistics. That is, they do not obey the Pauli exclusion principle, and more than one photon can occupy the same bound quantum state.

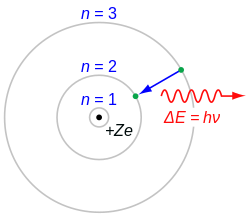

Photons are emitted when a charge is accelerated and emits synchrotron radiation. During a molecular, atomic, or nuclear transition to a lower energy level, the photons emitted have characteristic energies ranging from radio waves to gamma rays. Photons can also be emitted when a particle and its corresponding antiparticle are annihilated (for example, electron–positron annihilation).

Energy and momentum

In a quantum mechanical model, electromagnetic waves transfer energy in photons with energy proportional to frequency ()

where h is the Planck constant, a fundamental physical constant. The energy can be written with angular frequency () or wavelength (λ):

where ħ ≡ h/ 2π is called the reduced Planck constant and c is the speed of light.

The momentum of a photon

where k is the wave vector, where

- k ≡ |k| = 2π /λ is the wave number.

Since points in the direction of the photon's propagation, the magnitude of its momentum is

The photon energy can be written as E = pc where p is the magnitude of the momentum vector p. This consistent with the energy–momentum relation of special relativity,

when m = 0.

Polarization and spin angular momentum

The photon also carries spin angular momentum, which is related to photon polarization. (Beams of light also exhibit properties described as orbital angular momentum of light).

The angular momentum of the photon has two possible values, either +ħ or −ħ. These two possible values correspond to the two possible pure states of circular polarization. Collections of photons in a light beam may have mixtures of these two values; a linearly polarized light beam will act as if it were composed of equal numbers of the two possible angular momenta.

The spin angular momentum of light does not depend on its frequency, and was experimentally verified by C. V. Raman and Suri Bhagavantam in 1931.

Antiparticle annihilation

The collision of a particle with its antiparticle can create photons. In free space at least two photons must be created since, in the center of momentum frame, the colliding antiparticles have no net momentum, whereas a single photon always has momentum (determined by the photon's frequency or wavelength, which cannot be zero). Hence, conservation of momentum (or equivalently, translational invariance) requires that at least two photons are created, with zero net momentum. The energy of the two photons, or, equivalently, their frequency, may be determined from conservation of four-momentum.

Seen another way, the photon can be considered as its own antiparticle (thus an "antiphoton" is simply a normal photon with opposite momentum, equal polarization, and 180° out of phase). The reverse process, pair production, is the dominant mechanism by which high-energy photons such as gamma rays lose energy while passing through matter. That process is the reverse of "annihilation to one photon" allowed in the electric field of an atomic nucleus.

The classical formulae for the energy and momentum of electromagnetic radiation can be re-expressed in terms of photon events. For example, the pressure of electromagnetic radiation on an object derives from the transfer of photon momentum per unit time and unit area to that object, since pressure is force per unit area and force is the change in momentum per unit time.

Experimental checks on photon mass

Current commonly accepted physical theories imply or assume the photon to be strictly massless. If photons were not purely massless, their speeds would vary with frequency, with lower-energy (redder) photons moving slightly slower than higher-energy photons. Relativity would be unaffected by this; the so-called speed of light, c, would then not be the actual speed at which light moves, but a constant of nature which is the upper bound on speed that any object could theoretically attain in spacetime. Thus, it would still be the speed of spacetime ripples (gravitational waves and gravitons), but it would not be the speed of photons.

If a photon did have non-zero mass, there would be other effects as well. Coulomb's law would be modified and the electromagnetic field would have an extra physical degree of freedom. These effects yield more sensitive experimental probes of the photon mass than the frequency dependence of the speed of light. If Coulomb's law is not exactly valid, then that would allow the presence of an electric field to exist within a hollow conductor when it is subjected to an external electric field. This provides a means for precision tests of Coulomb's law. A null result of such an experiment has set a limit of m ≲ 10−14 eV/c2.

Sharper upper limits on the mass of light have been obtained in experiments designed to detect effects caused by the galactic vector potential. Although the galactic vector potential is large because the galactic magnetic field exists on great length scales, only the magnetic field would be observable if the photon is massless. In the case that the photon has mass, the mass term 1/2m2AμAμ would affect the galactic plasma. The fact that no such effects are seen implies an upper bound on the photon mass of m < 3×10−27 eV/c2. The galactic vector potential can also be probed directly by measuring the torque exerted on a magnetized ring. Such methods were used to obtain the sharper upper limit of 1.07×10−27 eV/c2 (10−36 Da) given by the Particle Data Group.

These sharp limits from the non-observation of the effects caused by the galactic vector potential have been shown to be model-dependent. If the photon mass is generated via the Higgs mechanism then the upper limit of m ≲ 10−14 eV/c2 from the test of Coulomb's law is valid.

Historical development

In most theories up to the eighteenth century, light was pictured as being made of particles. Since particle models cannot easily account for the refraction, diffraction and birefringence of light, wave theories of light were proposed by René Descartes (1637), Robert Hooke (1665), and Christiaan Huygens (1678); however, particle models remained dominant, chiefly due to the influence of Isaac Newton. In the early 19th century, Thomas Young and August Fresnel clearly demonstrated the interference and diffraction of light, and by 1850 wave models were generally accepted. James Clerk Maxwell's 1865 prediction that light was an electromagnetic wave – which was confirmed experimentally in 1888 by Heinrich Hertz's detection of radio waves – seemed to be the final blow to particle models of light.

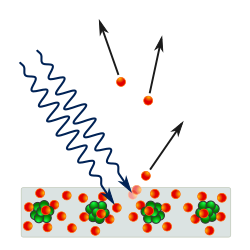

The Maxwell wave theory, however, does not account for all properties of light. The Maxwell theory predicts that the energy of a light wave depends only on its intensity, not on its frequency; nevertheless, several independent types of experiments show that the energy imparted by light to atoms depends only on the light's frequency, not on its intensity. For example, some chemical reactions are provoked only by light of frequency higher than a certain threshold; light of frequency lower than the threshold, no matter how intense, does not initiate the reaction. Similarly, electrons can be ejected from a metal plate by shining light of sufficiently high frequency on it (the photoelectric effect); the energy of the ejected electron is related only to the light's frequency, not to its intensity.

At the same time, investigations of black-body radiation carried out over four decades (1860–1900) by various researchers culminated in Max Planck's hypothesis that the energy of any system that absorbs or emits electromagnetic radiation of frequency ν is an integer multiple of an energy quantum E = hν . As shown by Albert Einstein, some form of energy quantization must be assumed to account for the thermal equilibrium observed between matter and electromagnetic radiation; for this explanation of the photoelectric effect, Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics.

Since the Maxwell theory of light allows for all possible energies of electromagnetic radiation, most physicists assumed initially that the energy quantization resulted from some unknown constraint on the matter that absorbs or emits the radiation. In 1905, Einstein was the first to propose that energy quantization was a property of electromagnetic radiation itself. Although he accepted the validity of Maxwell's theory, Einstein pointed out that many anomalous experiments could be explained if the energy of a Maxwellian light wave were localized into point-like quanta that move independently of one another, even if the wave itself is spread continuously over space. In 1909 and 1916, Einstein showed that, if Planck's law regarding black-body radiation is accepted, the energy quanta must also carry momentum p = h / λ , making them full-fledged particles.

As recounted in Robert Millikan's 1923 Nobel lecture, Einstein's 1905 predicted energy relationship was verified experimentally by 1916 but the local concept of the quanta remained unsettled. Most physicists were reluctant to believe that electromagnetic radiation itself might be particulate and thus an example of wave-particle duality. Then in 1922 Arthur Compton experiment showed that photons carried momentum proportional to their wave number (1922) in an experiment now called Compton scattering that appeared to clearly support a localized quantum model. At least for Millikan, this settled the matter. Compton received the Nobel Prize in 1927 for his scattering work.

Even after Compton's experiment, Niels Bohr, Hendrik Kramers and John Slater made one last attempt to preserve the Maxwellian continuous electromagnetic field model of light, the so-called BKS theory. An important feature of the BKS theory is how it treated the conservation of energy and the conservation of momentum. In the BKS theory, energy and momentum are only conserved on the average across many interactions between matter and radiation. However, refined Compton experiments showed that the conservation laws hold for individual interactions. Accordingly, Bohr and his co-workers gave their model "as honorable a funeral as possible". Nevertheless, the failures of the BKS model inspired Werner Heisenberg in his development of matrix mechanics.

By the late 1920, the pivotal question was how to unify Maxwell's wave theory of light with its experimentally observed particle nature. The answer to this question occupied Albert Einstein for the rest of his life, and was solved in quantum electrodynamics and its successor, the Standard Model. (See § Quantum field theory and § As a gauge boson, below.)

A few physicists persisted in developing semiclassical models in which electromagnetic radiation is not quantized, but matter appears to obey the laws of quantum mechanics. Although the evidence from chemical and physical experiments for the existence of photons was overwhelming by the 1970s, this evidence could not be considered as absolutely definitive; since it relied on the interaction of light with matter, and a sufficiently complete theory of matter could in principle account for the evidence.

In the 1970s and 1980s photon-correlation experiments definitively demonstrated quantum photon effects. These experiments produce results that cannot be explained by any classical theory of light, since they involve anticorrelations that result from the quantum measurement process. In 1974, the first such experiment was carried out by Clauser, who reported a violation of a classical Cauchy–Schwarz inequality. In 1977, Kimble et al. demonstrated an analogous anti-bunching effect of photons interacting with a beam splitter; this approach was simplified and sources of error eliminated in the photon-anticorrelation experiment of Grangier, Roger, & Aspect (1986); This work is reviewed and simplified further in Thorn, Neel, et al. (2004).

Nomenclature

The word quanta (singular quantum, Latin for how much) was used before 1900 to mean particles or amounts of different quantities, including electricity. In 1900, the German physicist Max Planck was studying black-body radiation, and he suggested that the experimental observations, specifically at shorter wavelengths, would be explained if the energy was "made up of a completely determinate number of finite equal parts", which he called "energy elements". In 1905, Albert Einstein published a paper in which he proposed that many light-related phenomena—including black-body radiation and the photoelectric effect—would be better explained by modelling electromagnetic waves as consisting of spatially localized, discrete energy quanta. He called these a light quantum (German: ein Lichtquant).

The name photon derives from the Greek word for light, φῶς (transliterated phôs). The name was used 1916 by the American physicist and psychologist Leonard T. Troland for a unit of illumination of the retina and in several other contexts before being adopted for physics. The use of the term photon for the light quantum was popularized by Gilbert N. Lewis, who used the term in a letter to Nature on 18 December 1926. Arthur Compton, who had performed a key experiment demonstrating light quanta, cited Lewis in the 1927 Solvay conference proceedings for suggesting the name photon. Einstein never did use the term.

In physics, a photon is usually denoted by the symbol γ (the Greek letter gamma). This symbol for the photon probably derives from gamma rays, which were discovered in 1900 by Paul Villard, named by Ernest Rutherford in 1903, and shown to be a form of electromagnetic radiation in 1914 by Rutherford and Edward Andrade. In chemistry and optical engineering, photons are usually symbolized by hν, which is the photon energy, where h is the Planck constant and the Greek letter ν (nu) is the photon's frequency.

Wave–particle duality and uncertainty principles

Photons obey the laws of quantum mechanics, and so their behavior has both wave-like and particle-like aspects. When a photon is detected by a measuring instrument, it is registered as a single, particulate unit. However, the probability of detecting a photon is calculated by equations that describe waves. This combination of aspects is known as wave–particle duality. For example, the probability distribution for the location at which a photon might be detected displays clearly wave-like phenomena such as diffraction and interference. A single photon passing through a double slit has its energy received at a point on the screen with a probability distribution given by its interference pattern determined by Maxwell's wave equations. However, experiments confirm that the photon is not a short pulse of electromagnetic radiation; a photon's Maxwell waves will diffract, but photon energy does not spread out as it propagates, nor does this energy divide when it encounters a beam splitter. Rather, the received photon acts like a point-like particle since it is absorbed or emitted as a whole by arbitrarily small systems, including systems much smaller than its wavelength, such as an atomic nucleus (≈10−15 m across) or even the point-like electron.

While many introductory texts treat photons using the mathematical techniques of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, this is in some ways an awkward oversimplification, as photons are by nature intrinsically relativistic. Because photons have zero rest mass, no wave function defined for a photon can have all the properties familiar from wave functions in non-relativistic quantum mechanics.[a] In order to avoid these difficulties, physicists employ the second-quantized theory of photons described below, quantum electrodynamics, in which photons are quantized excitations of electromagnetic modes.

Another difficulty is finding the proper analogue for the uncertainty principle, an idea frequently attributed to Heisenberg, who introduced the concept in analyzing a thought experiment involving an electron and a high-energy photon. However, Heisenberg did not give precise mathematical definitions of what the "uncertainty" in these measurements meant. The precise mathematical statement of the position–momentum uncertainty principle is due to Kennard, Pauli, and Weyl. The uncertainty principle applies to situations where an experimenter has a choice of measuring either one of two "canonically conjugate" quantities, like the position and the momentum of a particle. According to the uncertainty principle, no matter how the particle is prepared, it is not possible to make a precise prediction for both of the two alternative measurements: if the outcome of the position measurement is made more certain, the outcome of the momentum measurement becomes less so, and vice versa. A coherent state minimizes the overall uncertainty as far as quantum mechanics allows. Quantum optics makes use of coherent states for modes of the electromagnetic field. There is a tradeoff, reminiscent of the position–momentum uncertainty relation, between measurements of an electromagnetic wave's amplitude and its phase. This is sometimes informally expressed in terms of the uncertainty in the number of photons present in the electromagnetic wave, , and the uncertainty in the phase of the wave, . However, this cannot be an uncertainty relation of the Kennard–Pauli–Weyl type, since unlike position and momentum, the phase cannot be represented by a Hermitian operator.

Bose–Einstein model of a photon gas

In 1924, Satyendra Nath Bose derived Planck's law of black-body radiation without using any electromagnetism, but rather by using a modification of coarse-grained counting of phase space. Einstein showed that this modification is equivalent to assuming that photons are rigorously identical and that it implied a "mysterious non-local interaction", now understood as the requirement for a symmetric quantum mechanical state. This work led to the concept of coherent states and the development of the laser. In the same papers, Einstein extended Bose's formalism to material particles (bosons) and predicted that they would condense into their lowest quantum state at low enough temperatures; this Bose–Einstein condensation was observed experimentally in 1995. It was later used by Lene Hau to slow, and then completely stop, light in 1999 and 2001.

The modern view on this is that photons are, by virtue of their integer spin, bosons (as opposed to fermions with half-integer spin). By the spin-statistics theorem, all bosons obey Bose–Einstein statistics (whereas all fermions obey Fermi–Dirac statistics).

Stimulated and spontaneous emission

In 1916, Albert Einstein showed that Planck's radiation law could be derived from a semi-classical, statistical treatment of photons and atoms, which implies a link between the rates at which atoms emit and absorb photons. The condition follows from the assumption that functions of the emission and absorption of radiation by the atoms are independent of each other, and that thermal equilibrium is made by way of the radiation's interaction with the atoms. Consider a cavity in thermal equilibrium with all parts of itself and filled with electromagnetic radiation and that the atoms can emit and absorb that radiation. Thermal equilibrium requires that the energy density of photons with frequency (which is proportional to their number density) is, on average, constant in time; hence, the rate at which photons of any particular frequency are emitted must equal the rate at which they are absorbed.

Einstein began by postulating simple proportionality relations for the different reaction rates involved. In his model, the rate for a system to absorb a photon of frequency and transition from a lower energy to a higher energy is proportional to the number of atoms with energy and to the energy density of ambient photons of that frequency,

where is the rate constant for absorption. For the reverse process, there are two possibilities: spontaneous emission of a photon, or the emission of a photon initiated by the interaction of the atom with a passing photon and the return of the atom to the lower-energy state. Following Einstein's approach, the corresponding rate for the emission of photons of frequency and transition from a higher energy to a lower energy is

where is the rate constant for emitting a photon spontaneously, and is the rate constant for emissions in response to ambient photons (induced or stimulated emission). In thermodynamic equilibrium, the number of atoms in state and those in state must, on average, be constant; hence, the rates and must be equal. Also, by arguments analogous to the derivation of Boltzmann statistics, the ratio of and is where and are the degeneracy of the state and that of , respectively, and their energies, the Boltzmann constant and the system's temperature. From this, it is readily derived that

and

The and are collectively known as the Einstein coefficients.[85]

Einstein could not fully justify his rate equations, but claimed that it should be possible to calculate the coefficients , and once physicists had obtained "mechanics and electrodynamics modified to accommodate the quantum hypothesis". Not long thereafter, in 1926, Paul Dirac derived the rate constants by using a semiclassical approach, and, in 1927, succeeded in deriving all the rate constants from first principles within the framework of quantum theory. Dirac's work was the foundation of quantum electrodynamics, i.e., the quantization of the electromagnetic field itself. Dirac's approach is also called second quantization or quantum field theory; earlier quantum mechanical treatments only treat material particles as quantum mechanical, not the electromagnetic field.

Einstein was troubled by the fact that his theory seemed incomplete, since it did not determine the direction of a spontaneously emitted photon. A probabilistic nature of light-particle motion was first considered by Newton in his treatment of birefringence and, more generally, of the splitting of light beams at interfaces into a transmitted beam and a reflected beam. Newton hypothesized that hidden variables in the light particle determined which of the two paths a single photon would take. Similarly, Einstein hoped for a more complete theory that would leave nothing to chance, beginning his separation from quantum mechanics. Ironically, Max Born's probabilistic interpretation of the wave function was inspired by Einstein's later work searching for a more complete theory.

Quantum field theory

Quantization of the electromagnetic field

In 1910, Peter Debye derived Planck's law of black-body radiation from a relatively simple assumption. He decomposed the electromagnetic field in a cavity into its Fourier modes, and assumed that the energy in any mode was an integer multiple of , where is the frequency of the electromagnetic mode. Planck's law of black-body radiation follows immediately as a geometric sum. However, Debye's approach failed to give the correct formula for the energy fluctuations of black-body radiation, which were derived by Einstein in 1909.

In 1925, Born, Heisenberg and Jordan reinterpreted Debye's concept in a key way. As may be shown classically, the Fourier modes of the electromagnetic field—a complete set of electromagnetic plane waves indexed by their wave vector k and polarization state—are equivalent to a set of uncoupled simple harmonic oscillators. Treated quantum mechanically, the energy levels of such oscillators are known to be , where is the oscillator frequency. The key new step was to identify an electromagnetic mode with energy as a state with photons, each of energy . This approach gives the correct energy fluctuation formula.

Dirac took this one step further. He treated the interaction between a charge and an electromagnetic field as a small perturbation that induces transitions in the photon states, changing the numbers of photons in the modes, while conserving energy and momentum overall. Dirac was able to derive Einstein's and coefficients from first principles, and showed that the Bose–Einstein statistics of photons is a natural consequence of quantizing the electromagnetic field correctly (Bose's reasoning went in the opposite direction; he derived Planck's law of black-body radiation by assuming B–E statistics). In Dirac's time, it was not yet known that all bosons, including photons, must obey Bose–Einstein statistics.

Dirac's second-order perturbation theory can involve virtual photons, transient intermediate states of the electromagnetic field; the static electric and magnetic interactions are mediated by such virtual photons. In such quantum field theories, the probability amplitude of observable events is calculated by summing over all possible intermediate steps, even ones that are unphysical; hence, virtual photons are not constrained to satisfy , and may have extra polarization states; depending on the gauge used, virtual photons may have three or four polarization states, instead of the two states of real photons. Although these transient virtual photons can never be observed, they contribute measurably to the probabilities of observable events.

Second-order and higher-order perturbation calculations can give infinite contributions to the sum. Such unphysical results are corrected for using the technique of renormalization.

Other virtual particles may contribute to the summation as well; for example, two photons may interact indirectly through virtual electron–positron pairs. Such photon–photon scattering (see two-photon physics), as well as electron–photon scattering, is meant to be one of the modes of operations of the planned particle accelerator, the International Linear Collider.

In modern physics notation, the quantum state of the electromagnetic field is written as a Fock state, a tensor product of the states for each electromagnetic mode

where represents the state in which photons are in the mode . In this notation, the creation of a new photon in mode (e.g., emitted from an atomic transition) is written as . This notation merely expresses the concept of Born, Heisenberg and Jordan described above, and does not add any physics.

As a gauge boson

The electromagnetic field can be understood as a gauge field, i.e., as a field that results from requiring that a gauge symmetry holds independently at every position in spacetime. For the electromagnetic field, this gauge symmetry is the Abelian U(1) symmetry of complex numbers of absolute value 1, which reflects the ability to vary the phase of a complex field without affecting observables or real valued functions made from it, such as the energy or the Lagrangian.

The quanta of an Abelian gauge field must be massless, uncharged bosons, as long as the symmetry is not broken; hence, the photon is predicted to be massless, and to have zero electric charge and integer spin. The particular form of the electromagnetic interaction specifies that the photon must have spin ±1; thus, its helicity must be . These two spin components correspond to the classical concepts of right-handed and left-handed circularly polarized light. However, the transient virtual photons of quantum electrodynamics may also adopt unphysical polarization states.

In the prevailing Standard Model of physics, the photon is one of four gauge bosons in the electroweak interaction; the other three are denoted W+, W− and Z0 and are responsible for the weak interaction. Unlike the photon, these gauge bosons have mass, owing to a mechanism that breaks their SU(2) gauge symmetry. The unification of the photon with W and Z gauge bosons in the electroweak interaction was accomplished by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, for which they were awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics. Physicists continue to hypothesize grand unified theories that connect these four gauge bosons with the eight gluon gauge bosons of quantum chromodynamics; however, key predictions of these theories, such as proton decay, have not been observed experimentally.

Hadronic properties

Measurements of the interaction between energetic photons and hadrons show that the interaction is much more intense than expected by the interaction of merely photons with the hadron's electric charge. Furthermore, the interaction of energetic photons with protons is similar to the interaction of photons with neutrons in spite of the fact that the electrical charge structures of protons and neutrons are substantially different. A theory called vector meson dominance (VMD) was developed to explain this effect. According to VMD, the photon is a superposition of the pure electromagnetic photon, which interacts only with electric charges, and vector mesons, which mediate the residual nuclear force. However, if experimentally probed at very short distances, the intrinsic structure of the photon appears to have as components a charge-neutral flux of quarks and gluons, quasi-free according to asymptotic freedom in QCD. That flux is described by the photon structure function. A review by Nisius (2000) presented a comprehensive comparison of data with theoretical predictions.

Contributions to the mass of a system

The energy of a system that emits a photon is decreased by the energy of the photon as measured in the rest frame of the emitting system, which may result in a reduction in mass in the amount . Similarly, the mass of a system that absorbs a photon is increased by a corresponding amount. As an application, the energy balance of nuclear reactions involving photons is commonly written in terms of the masses of the nuclei involved, and terms of the form for the gamma photons (and for other relevant energies, such as the recoil energy of nuclei).

This concept is applied in key predictions of quantum electrodynamics (QED, see above). In that theory, the mass of electrons (or, more generally, leptons) is modified by including the mass contributions of virtual photons, in a technique known as renormalization. Such "radiative corrections" contribute to a number of predictions of QED, such as the magnetic dipole moment of leptons, the Lamb shift, and the hyperfine structure of bound lepton pairs, such as muonium and positronium.

Since photons contribute to the stress–energy tensor, they exert a gravitational attraction on other objects, according to the theory of general relativity. Conversely, photons are themselves affected by gravity; their normally straight trajectories may be bent by warped spacetime, as in gravitational lensing, and their frequencies may be lowered by moving to a higher gravitational potential, as in the Pound–Rebka experiment. However, these effects are not specific to photons; exactly the same effects would be predicted for classical electromagnetic waves.

In matter

Light that travels through transparent matter does so at a lower speed than c, the speed of light in vacuum. The factor by which the speed is decreased is called the refractive index of the material. In a classical wave picture, the slowing can be explained by the light inducing electric polarization in the matter, the polarized matter radiating new light, and that new light interfering with the original light wave to form a delayed wave. In a particle picture, the slowing can instead be described as a blending of the photon with quantum excitations of the matter to produce quasi-particles known as polaritons. Polaritons have a nonzero effective mass, which means that they cannot travel at c. Light of different frequencies may travel through matter at different speeds; this is called dispersion (not to be confused with scattering). In some cases, it can result in extremely slow speeds of light in matter. The effects of photon interactions with other quasi-particles may be observed directly in Raman scattering and Brillouin scattering.

Photons can be scattered by matter. For example, photons scatter so many times in the solar radiative zone after leaving the core of the Sun that radiant energy takes about a million years to reach the convection zone. However, photons emitted from the sun's photosphere take only 8.3 minutes to reach Earth.

Photons can also be absorbed by nuclei, atoms or molecules, provoking transitions between their energy levels. A classic example is the molecular transition of retinal (C20H28O), which is responsible for vision, as discovered in 1958 by Nobel laureate biochemist George Wald and co-workers. The absorption provokes a cis–trans isomerization that, in combination with other such transitions, is transduced into nerve impulses. The absorption of photons can even break chemical bonds, as in the photodissociation of chlorine; this is the subject of photochemistry.

Technological applications

Photons have many applications in technology. These examples are chosen to illustrate applications of photons per se, rather than general optical devices such as lenses, etc. that could operate under a classical theory of light. The laser is an important application and is discussed above under stimulated emission.

Individual photons can be detected by several methods. The classic photomultiplier tube exploits the photoelectric effect: a photon of sufficient energy strikes a metal plate and knocks free an electron, initiating an ever-amplifying avalanche of electrons. Semiconductor charge-coupled device chips use a similar effect: an incident photon generates a charge on a microscopic capacitor that can be detected. Other detectors such as Geiger counters use the ability of photons to ionize gas molecules contained in the device, causing a detectable change of conductivity of the gas.

Planck's energy formula is often used by engineers and chemists in design, both to compute the change in energy resulting from a photon absorption and to determine the frequency of the light emitted from a given photon emission. For example, the emission spectrum of a gas-discharge lamp can be altered by filling it with (mixtures of) gases with different electronic energy level configurations.

Under some conditions, an energy transition can be excited by "two" photons that individually would be insufficient. This allows for higher resolution microscopy, because the sample absorbs energy only in the spectrum where two beams of different colors overlap significantly, which can be made much smaller than the excitation volume of a single beam (see two-photon excitation microscopy). Moreover, these photons cause less damage to the sample, since they are of lower energy.

In some cases, two energy transitions can be coupled so that, as one system absorbs a photon, another nearby system "steals" its energy and re-emits a photon of a different frequency. This is the basis of fluorescence resonance energy transfer, a technique that is used in molecular biology to study the interaction of suitable proteins.

Several different kinds of hardware random number generators involve the detection of single photons. In one example, for each bit in the random sequence that is to be produced, a photon is sent to a beam-splitter. In such a situation, there are two possible outcomes of equal probability. The actual outcome is used to determine whether the next bit in the sequence is 0 or 1.

Quantum optics and computation

Much research has been devoted to applications of photons in the field of quantum optics. Photons seem well-suited to be elements of an extremely fast quantum computer, and the quantum entanglement of photons is a focus of research. Nonlinear optical processes are another active research area, with topics such as two-photon absorption, self-phase modulation, modulational instability and optical parametric oscillators. However, such processes generally do not require the assumption of photons per se; they may often be modeled by treating atoms as nonlinear oscillators. The nonlinear process of spontaneous parametric down conversion is often used to produce single-photon states. Finally, photons are essential in some aspects of optical communication, especially for quantum cryptography.

Two-photon physics studies interactions between photons, which are rare. In 2018, Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers announced the discovery of bound photon triplets, which may involve polaritons.