Nanoparticles are classified as having at least one of its dimensions in the range of 1-100 nanometers (nm). The small size of nanoparticles allows them to have unique characteristics which may not be possible on the macro-scale. Self-assembly is the spontaneous organization of smaller subunits to form larger, well-organized patterns. For nanoparticles, this spontaneous assembly is a consequence of interactions between the particles aimed at achieving a thermodynamic equilibrium and reducing the system's free energy. The thermodynamics definition of self-assembly was introduced by Professor Nicholas A. Kotov. He describes self-assembly as a process where components of the system acquire non-random spatial distribution with respect to each other and the boundaries of the system. This definition allows one to account for mass and energy fluxes taking place in the self-assembly processes.

This process occurs at all size scales, in the form of either static or dynamic self-assembly. Static self-assembly utilizes interactions amongst the nano-particles to achieve a free-energy minimum. In solutions, it is an outcome of random motion of particles and the affinity of their binding sites for one another. A dynamic system is forced to not reach equilibrium by supplying the system with a continuous, external source of energy to balance attractive and repulsive forces. Magnetic fields, electric fields, ultrasound fields, light fields, etc. have all been used as external energy sources to program robot swarms at small scales. Static self-assembly is significantly slower compared to dynamic self-assembly as it depends on the random chemical interactions between particles.

Self assembly can be directed in two ways. The first is by manipulating the intrinsic properties which includes changing the directionality of interactions or changing particle shapes. The second is through external manipulation by applying and combining the effects of several kinds of fields to manipulate the building blocks into doing what is intended. To do so correctly, an extremely high level of direction and control is required and developing a simple, efficient method to organize molecules and molecular clusters into precise, predetermined structures is crucial.

History

In 1959, physicist Richard Feynman gave a talk titled "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom" to the American Physical Society. He imagined a world in which "we could arrange atoms one by one, just as we want them." This idea set the stage for the bottom-up synthesis approach in which constituent components interact to form higher-ordered structures in a controllable manner. The study of self-assembly of nanoparticles began with recognition that some properties of atoms and molecules enable them to arrange themselves into patterns. A variety of applications where the self-assembly of nanoparticles might be useful. For example, building sensors or computer chips.

Definition

Self-assembly is defined as a process in which individual units of material associate with themselves spontaneously into a defined and organized structure or larger units with minimal external direction. Self-assembly is recognized as a highly useful technique to achieve outstanding qualities in both organic and inorganic nanostructures.

According to George M. Whitesides, "Self-assembly is the autonomous organization of components into patterns or structures without human intervention." Another definition by Serge Palacin & Renaud Demadrill is "Self-assembly is a spontaneous and reversible process that brings together in a defined geometry randomly moving distinct bodies through selective bonding forces."

Importance

To commemorate the 125th anniversary of Science magazine, 25 urgent questions were asked for scientists to solve, and the only one that relates to chemistry is"How Far Can We Push Chemical Self-Assembly?" Because self-assembly is the only approach for building a wide variety of nanostructures, the need for increasing complexity is growing. To learn from nature and build the nanoworld with noncovalent bonds, more research is needed in this area. Self assembly of nanomaterials is currently considered broadly for nano-structuring and nano-fabrication because of its simplicity, versatility and spontaneity. Exploiting the properties of the nano assembly holds promise as a low-cost and high-yield technique for a wide range of scientific and technological applications and is a key research effort in nanotechnology, molecular robotics, and molecular computation. A summary of benefits of self-assembly in fabrication is listed below:

- Self-assembly is a scalable and parallel process which can involve large numbers of components in a short timeframe.

- Can result in structural dimensions across orders of magnitude, from nanoscale to macroscale.

- Is relatively inexpensive compared to the top-down assembly approach, which often consumes large amounts of finite resources.

- Natural processes that drive self-assembly tend to be highly reproducible. The existence of life is strongly dependent on the reproducibility of self-assembly.

Challenges

There exist several outstanding challenges in self-assembly, due to a variety of competing factors. Currently self-assembly is difficult to control on large scales, and to be widely applied we will need to ensure high degrees of reproducibility at these scales. The fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic mechanisms of self-assembly are poorly understood - the basic principles of atomistic and macroscale processes can be significantly different than those for nanostructures. Concepts related to thermal motion and capillary action influence equilibrium timescales and kinetic rates that are not well defined in self-assembling systems.

Top-down vs bottom-up synthesis

The top-down approach is breaking down of a system into small components, while bottom-up is assembling sub-systems into larger system. A bottom-up approach for nano-assembly is a primary research target for nano-fabrication because top down synthesis is expensive (requiring external work) and is not selective on very small length scales, but is currently the primary mode of industrial fabrication. Generally, the maximum resolution of the top-down products is much coarser than those of bottom-up; therefore, an accessible strategy to bridge "bottom-up" and "top-down", is realizable by the principles of self-assembly. By controlling local intermolecular forces to find the lowest-energy configuration, self-assembly can be guided by templates to generate similar structures to those currently fabricated by top-down approaches. This so-called bridging will enable fabrication of materials with the fine resolution of bottom-up methods and the larger range and arbitrary structure of top-down processes. Furthermore, in some cases components are too small for top-down synthesis, so self-assembly principles are required to realize these novel structures.

Classification

Nanostructures can be organized into groups based on their size, function, and structure; this organization is useful to define the potential of the field.

By size

Among the more sophisticated and structurally complex nanostructures currently available are organic macromolecules, wherein their assembly relies on the placement of atoms into molecular or extended structures with atomic-level precision. It is now known that organic compounds can be conductors, semiconductors, and insulators, thus one of the main opportunities in nanomaterials science is to use organic synthesis and molecular design to make electronically useful structures. Structural motifs in these systems include colloids, small crystals, and aggregates on the order of 1-100 nm.

By function

Nanostructured materials can also be classed according to their functions, for example nanoelectronics and information technology (IT). Lateral dimensions used in information storage are shrinking from the micro- to the nanoscale as fabrication technologies improve. Optical materials are important in the development of miniaturized information storage because light has many advantages for storage and transmission over electronic methods. Quantum dots - most commonly CdSe nanoparticles having diameters of tens of nm, and with protective surface coatings - are notable for their ability to fluoresce over a broad range of the visible spectrum, with the controlling parameter being size.

By structure

Certain structural classes are especially relevant to nanoscience. As the dimensions of structures become smaller, their surface area-to-volume ratio increases. Much like molecules, nanostructures at small enough scales are essentially "all surface". The mechanical properties of materials are strongly influenced by these surface structures. Fracture strength and character, ductility, and various mechanical moduli all depend on the substructure of the materials over a range of scales. The opportunity to redevelop a science of materials that are nanostructured by design is largely open.

Thermodynamics

Self-assembly is an equilibrium process, i.e. the individual and assembled components exist in equilibrium. In addition, the flexibility and the lower free energy conformation is usually a result of a weaker intermolecular force between self-assembled moieties and is essentially enthalpic in nature.

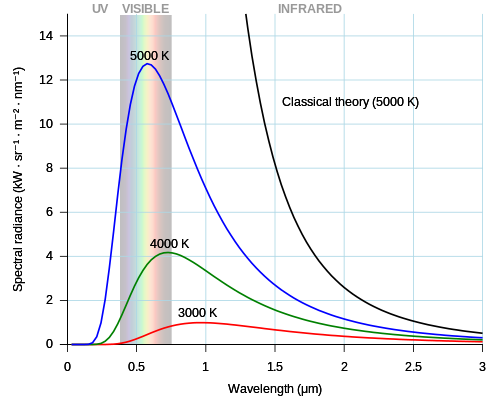

The thermodynamics of the self-assembly process can be represented by a simple Gibbs free energy equation:

where if is negative, self-assembly is a spontaneous process. is the enthalpy change of the process and is largely determined by the potential energy/intermolecular forces between the assembling entities. is the change in entropy associated with the formation of the ordered arrangement. In general, the organization is accompanied by a decrease in entropy and in order for the assembly to be spontaneous the enthalpy term must be negative and in excess of the entropy term. This equation shows that as the value of approaches the value of and above a critical temperature, the self-assembly process will become progressively less likely to occur and spontaneous self-assembly will not happen.

The self-assembly is governed by the normal processes of nucleation and growth. Small assemblies are formed because of their increased lifetime as the attractive interactions between the components lower the Gibbs free energy. As the assembly grows, the Gibbs free energy continues to decrease until the assembly becomes stable enough to last for a long period of time. The necessity of the self-assembly to be an equilibrium process is defined by the organization of the structure which requires non-ideal arrangements to be formed before the lowest energy configuration is found.

Kinetics

The ultimate driving force in self-assembly is energy minimization and the corresponding evolution towards equilibrium, but kinetic effects can also play a very strong role. These kinetic effects, such as trapping in metastable states, slow coarsening kinetics, and pathway-dependent assembly, are often viewed as complications to be overcome in, for example, the formation of block copolymers.

Amphiphile self-assembly is an essential bottom-up approach of fabricating advanced functional materials. Self-assembled materials with desired structures are often obtained through thermodynamic control. Here, we demonstrate that the selection of kinetic pathways can lead to drastically different self-assembled structures, underlining the significance of kinetic control in self-assembly.

Defects

There are two kinds of defects: Equilibrium defects, and Non-Equilibrium defects. Self-assembled structures contain defects. Dislocations caused during the assembling of nanomaterials can majorly affect the final structure and in general defects are never completely avoidable. Current research on defects is focused on controlling defect density. In most cases, the thermodynamic driving force for self-assembly is provided by weak intermolecular interactions and is usually of the same order of magnitude as the entropy term. In order for a self-assembling system to reach the minimum free energy configuration, there has to be enough thermal energy to allow the mass transport of the self-assembling molecules. For defect formation, the free energy of single defect formation is given by:

The enthalpy term, does not necessarily reflect the intermolecular forces between the molecules, it is the energy cost associated with disrupting the pattern and may be thought of as a region where optimum arrangement does not occur and the reduction of enthalpy associated with ideal self-assembly did not occur. An example of this can be seen in a system of hexagonally packed cylinders where defect regions of lamellar structure exist.

If is negative, there will be a finite number of defects in the system and the concentration will be given by:

N is the number of defects in a matrix of N0 self-assembled particles or features and is the activation energy of defect formation. The activation energy, , should not be confused with . The activation energy represents the energy difference between the initial ideally arranges state and a transition state towards the defective structure. At low defect concentrations, defect formation is entropy driven until a critical concentration of defects allows the activation energy term to compensate for entropy. There is usually an equilibrium defect density indicated at the minimum free energy. The activation energy for defect formation increases this equilibrium defect density.

Particle Interaction

Intermolecular forces govern the particle interaction in self-assembled systems. The forces tend to be intermolecular in type rather than ionic or covalent because ionic or covalent bonds will "lock" the assembly into non-equilibrium structures. The types intermolecular forces seen in self-assembly processes are van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, and weak polar forces, just to name a few. In self-assembly, regular structural arrangements are frequently observed, therefore there must be a balance of attractive and repulsive between molecules otherwise an equilibrium distance will not exist between the particles. The repulsive forces can be electron cloud-electron cloud overlap or electrostatic repulsion.

Design nanoparticle self-assembly structure

Self-assembly of nanoparticles is driven by either maximization of packing density or minimization of the contact area between particles according to hard or soft nanoparticles. Examples of hard nanoparticles are: silica, fullerenes; soft nanoparticles are often organic nanoparticles, block copolymer micelles, DNA nanoparticles. The ordered self-assembly structure of nanoparticles is called superlattice.

Hard nanoparticles

For hard particles, Pauling's rules are useful in understanding the structure of ionic compounds in the early days, and the later entropy maximization principle shows favor of dense packing in the system. Therefore, finding the densest packing for a given shape is a starting point for predicting the structure of hard nanoparticle superlattices. For spherical particles, the densest packings are face-centered cubic and hexagonal close-packed from the Kepler–Hales theorem.

Different particle shapes / polyhedra create diverse complex packing structures in order to minimize the entropy of the system. By computer simulations, four structure categories are classified for faceted polyhedra nanoparticles according to their long-range order and short-range order, which are liquid crystals, plastic crystals, crystals, and disordered structures.

Soft nanoparticles

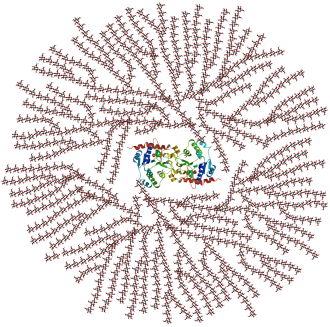

Most soft nanoparticles have core–shell structures. The semiflexible surface ligands soften the interaction of the cores and create a more spherical shape than the underlying core from uniform coverage. The surface ligands can be chosen from surfactants, polymers, DNA, ions, etc. Tuning the structure of superlattices can be achieved by varying the amount of surface ligands. Their "soft" behavior results in different self-assembly rules from hard particles, where Pauling's rules expired.

To tailor the superlattice structure of soft nanoparticles, six design rules of spherical nanoparticle superlattice are established based on the study of metal–DNA nanoparticles:

- The thermodynamic product of equal radius nanoparticle has the maximum nearest neighbors that DNA connections can form.

- The kinetic product of two similarly stable lattices can be produced by slowing the individual DNA linker dehybridize and rehybridize rate.

- The assembly and packing behavior is determined by the overall hydrodynamic radius of a nanoparticle rather than the size of the core or the shell.

- The hydrodynamic radius ratio or the size ratio of two nanoparticles in a binary system indicates the thermodynamically favored crystal structure.

- A system with the same size ratio and DNA linker ratio will give the same thermodynamic product.

- The most stable crystal structure is the maximization of the all possible DNA sequence-specific hybridization interactions.

Processing

The processes by which nanoparticles self-assemble are widespread and important. Understanding why and how self-assembly occurs is key in reproducing and optimizing results. Typically, nanoparticles will self-assemble for one or both of two reasons: molecular interactions and external direction.

Self-assembly by molecular interactions

Nanoparticles have the ability to assemble chemically through covalent or noncovalent interactions with their capping ligand. The terminal functional group(s) on the particle are known as capping ligands. As these ligands tend to be complex and sophisticated, self-assembly can provide a simpler pathway for nanoparticle organization by synthesizing efficient functional groups. For instance, DNA oligomers have been a key ligand for nanoparticle building blocks to be self-assembling via sequence-based specific organization. However, to deliver precise and scalable (programmable) assembly for a desired structure, a careful positioning of ligand molecules onto the nanoparticle counterpart should be required at the building block (precursor) level, such as direction, geometry, morphology, affinity, etc. The successful design of ligand-building block units can play an essential role in manufacturing a wide-range of new nano systems, such as nanosensor systems, nanomachines/nanobots, nanocomputers, and many more uncharted systems.

Intermolecular forces

Nanoparticles can self-assemble as a result of their intermolecular forces. As systems look to minimize their free energy, self-assembly is one option for the system to achieve its lowest free energy thermodynamically. Nanoparticles can be programmed to self-assemble by changing the functionality of their side groups, taking advantage of weak and specific intermolecular forces to spontaneously order the particles. These direct interparticle interactions can be typical intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding or Van der Waals forces, but can also be internal characteristics, such as hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity. For example, lipophilic nanoparticles have the tendency to self-assemble and form crystals as solvents are evaporated. While these aggregations are based on intermolecular forces, external factors such as temperature and pH also play a role in spontaneous self-assembly.

Hamaker interaction

As nanoparticle interactions take place on a nanoscale, the particle interactions must be scaled similarly. Hamaker interactions take into account the polarization characteristics of a large number of nearby particles and the effects they have on each other. Hamaker interactions sum all of the forces between all particles and the solvent(s) involved in the system. While Hamaker theory generally describes a macroscopic system, the vast number of nanoparticles in a self-assembling system allows the term to be applicable. Hamaker constants for nanoparticles are calculated using Lifshitz theory, and can often be found in literature.

| Material | A131 |

|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | 22 |

| -Fe2O3 | 26 |

| α-Fe2O3 | 29 |

| Ag | 33 |

| Au | 45 |

| All values reported in zJ | |

Externally directed self-assembly

The natural ability of nanoparticles to self-assemble can be replicated in systems that do not intrinsically self-assemble. Directed self-assembly (DSA) attempts to mimic the chemical properties of self-assembling systems, while simultaneously controlling the thermodynamic system to maximize self-assembly.

Electric and magnetic fields

External fields are the most common directors of self-assembly. Electric and magnetic fields allow induced interactions to align the particles. The fields take advantage of the polarizability of the nanoparticle and its functional groups. When these field-induced interactions overcome random Brownian motion, particles join to form chains and then assemble. At more modest field strengths, ordered crystal structures are established due to the induced dipole interactions. Electric and magnetic field direction requires a constant balance between thermal energy and interaction energies.

Flow fields

Common ways of incorporating nanoparticle self-assembly with a flow include Langmuir-Blodgett, dip coating, flow coating and spin coating.

Macroscopic viscous flow

Macroscopic viscous flow fields can direct self-assembly of a random solution of particles into ordered crystals. However, the assembled particles tend to disassemble when the flow is stopped or removed. Shear flows are useful for jammed suspensions or random close packing. As these systems begin in nonequilibrium, flow fields are useful in that they help the system relax towards ordered equilibrium. Flow fields are also useful when dealing with complex matrices that themselves have rheological behavior. Flow can induce anisotropic viseoelastic stresses, which helps to overcome the matrix and cause self-assembly.

Combination of fields

The most effective self-assembly director is a combination of external force fields. If the fields and conditions are optimized, self-assembly can be permanent and complete. When a field combination is used with nanoparticles that are tailored to be intrinsically responsive, the most complete assembly is observed. Combinations of fields allow the benefits of self-assembly, such as scalability and simplicity, to be maintained while being able to control orientation and structure formation. Field combinations possess the greatest potential for future directed self-assembly work.

Nanomaterial Interfaces

Applications of nanotechnology often depend on the lateral assembly and spatial arrangement of nanoparticles at interfaces. Chemical reactions can be induced at solid/liquid interfaces by manipulating the location and orientation of functional groups of nanoparticles. This can be achieved through external stimuli or direct manipulation. Changing the parameters of the external stimuli, such as light and electric fields, has a direct effect on assembled nanostructures. Likewise, direct manipulation takes advantage of photolithography techniques, along with scanning probe microscopy (SPM), and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), just to name a few.

Solid interfaces

Nano-particles can self-assemble on solid surfaces after external forces (like magnetic and electric) are applied. Templates made of microstructures, like carbon nanotubes or block polymers, can also be used to assist in self-assembly. They cause directed self-assembly (DSA), in which active sites are embedded to selectively induce nanoparticle deposition. Such templates are objects onto which different particles can be arranged into a structure with a morphology similar to that of the template. Carbon nanotubes (microstructures), single molecules, or block copolymers are common templates. Nanoparticles are often shown to self-assemble within distances of nanometers and micrometers, but block copolymer templates can be used to form well-defined self-assemblies over macroscopic distances. By incorporating active sites to the surfaces of nanotubes and polymers, the functionalization of these templates can be transformed to favor self-assembly of specified nanoparticles.

Liquid interfaces

Understanding the behavior of nanoparticles at liquid interfaces is essential for integrating them into electronics, optics, sensing, and catalysis devices. Molecular arrangements at liquid/liquid interfaces are uniform. Often, they also provide a defect-correcting platform and thus, liquid/liquid interfaces are ideal for self-assembly. Upon self-assembly, the structural and spatial arrangements can be determined via X-ray diffraction and optical reflectance. The number of nanoparticles involved in self-assembly can be controlled by manipulating the concentration of the electrolyte, which can be in the aqueous or the organic phase. Higher electrolyte concentrations correspond to decreased spacing between the nanoparticles. Pickering and Ramsden worked with oil/water (O/W) interfaces to portray this idea. Pickering and Ramsden explained the idea of pickering emulsions when experimenting with paraffin-water emulsions with solid particles like iron oxide and silicon dioxide. They observed that the micron-sized colloids generated a resistant film at the interface between the two immiscible phases, inhibiting the coalescence of the emulsion drops. These Pickering emulsions are formed from the self-assembly of colloidal particles in two-part liquid systems, such as oil-water systems. The desorption energy, which is directly related to the stability of emulsions depends on the particle size, particles interacting with each other, and particles interacting with oil and water molecules.

A decrease in total free energy was observed to be a result of the assembly of nanoparticles at an oil/water interface. When moving to the interface, particles reduce the unfavorable contact between the immiscible fluids and decrease the interfacial energy. The decrease in total free energy for microscopic particles is much larger than that of thermal energy, resulting in an effective confinement of large colloids to the interface. Nanoparticles are restricted to the interface by an energy reduction comparable to thermal energy. Thus, nanoparticles are easily displaced from the interface. A constant particle exchange then occurs at the interface at rates dependent on particle size. For the equilibrium state of assembly, the total gain in free energy is smaller for smaller particles. Thus, large nanoparticle assemblies are more stable. The size dependence allows nanoparticles to self-assemble at the interface to attain its equilibrium structure. Micrometer- size colloids, on the other hand, may be confined in a non-equilibrium state.

Applications

Electronics

Self-assembly of nanoscale structures from functional nanoparticles has provided a powerful path to developing small and powerful electronic components. Nanoscale objects have always been difficult to manipulate because they cannot be characterized by molecular techniques and they are too small to observe optically. But with advances in science and technology, there are now many instruments for observing nanostructures. Imaging methods span electron, optical and scanning probe microscopy, including combined electron-scanning probe and near-field opticalscanning probe instruments. Nanostructure characterization tools include advanced optical spectro-microscopy (linear, non-linear, tipenhanced and pump-probe) and Auger and x-ray photoemission for surface analysis. 2D self-assembly monodisperse particle colloids has a strong potential in dense magnetic storage media. Each colloid particle has the ability to store information as known as binary number 0 and 1 after applying it to a strong magnetic field. In the meantime, it requires a nanoscale sensor or detector in order to selectively choose the colloid particle. The microphase separation of block copolymers shows a great deal of promise as a means of generating regular nanopatterns at surfaces. They may, therefore, find application as a means to novel nanomaterials and nanoelectronics device structures.

Biological applications

Drug delivery

Block copolymers are a well-studied and versatile class of self-assembling materials characterized by chemically distinct polymer blocks that are covalently bonded. This molecular architecture of the covalent bond enhancement is what causes block copolymers to spontaneously form nanoscale patterns. In block copolymers, covalent bonds frustrate the natural tendency of each individual polymer to remain separate (in general, different polymers, do not like to mix), so the material assembles into a nano-pattern instead. These copolymers offer the ability to self-assemble into uniform, nanosized micelles and accumulate in tumors via the enhanced permeability and retention effect. Polymer composition can be chosen to control the micelle size and compatibility with the drug of choice. The challenges of this application are the difficulty of reproducing or controlling the size of self-assembly nano micelle, preparing predictable size-distribution, and the stability of the micelle with high drug load content.

Magnetic drug delivery

Magnetic nanochains are a class of new magnetoresponsive and superparamagnetic nanostructures with highly anisotropic shapes (chain-like) which can be manipulated using magnetic field and magnetic field gradient. The magnetic nanochains possess attractive properties which are significant added value for many potential uses including magneto-mechanical actuation-associated nanomedicines in low and super-low frequency alternating magnetic field and magnetic drug delivery.

Cell imaging

Nanoparticles have good biological labeling and sensing because of brightness and photostability; thus, certain self-assembled nanoparticles can be used as imaging contrast in various systems. Combined with polymer cross-linkers, the fluorescence intensity can also be enhanced. Surface modification with functional groups, can also lead to selective biological labeling. Self-assembled nanoparticles are also more biocompatible compared to standard drug delivery systems.