Romanticism (also the

Romantic era or the

Romantic period) was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe toward the end of the 18th century and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1850. It was partly a reaction to the

Industrial Revolution,

[1] the aristocratic social and political norms of the

Age of Enlightenment, and the scientific

rationalization of nature.

[2] It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography,

[3] education

[4] and the

natural sciences.

[5] It had a significant and complex effect on politics, and while for much of the Romantic period it was associated with

liberalism and

radicalism, its long-term effect on the growth of

nationalism was perhaps more significant.

The movement emphasized intense emotion as an authentic source of

aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as

apprehension,

horror and terror, and

awe—especially that which is experienced in confronting the new aesthetic categories of the

sublimity and beauty of nature. It considered

folk art and ancient custom to be noble statuses, but also valued spontaneity, as in the musical

impromptu. In contrast to the

rational and

Classicist ideal models, Romanticism revived

medievalism [6]. and elements of art and narrative perceived to be authentically medieval in an attempt to escape population growth,

urban sprawl, and

industrialism.

Although the movement was rooted in the German

Sturm und Drang movement, which preferred intuition and emotion to the rationalism of the Enlightenment, the events and ideologies of the

French Revolution were also proximate factors. Romanticism assigned a high value to the achievements of 'heroic' individualists and artists, whose examples, it maintained, would raise the quality of society. It also promoted the individual imagination as a critical authority allowed of freedom from classical notions of form in art. There was a strong recourse to historical and natural inevitability, a

Zeitgeist, in the representation of its ideas. In the second half of the 19th century,

Realism was offered as a polar opposite to Romanticism.

[7] The decline of Romanticism during this time was associated with multiple processes, including social and political changes and the spread of nationalism.

[8]

Defining Romanticism

Basic characteristics

Defining the nature of Romanticism may be approached from the starting point of the primary importance of the free expression of the feelings of the artist. The importance the Romantics placed on emotion is summed up in the remark of the German painter

Caspar David Friedrich that "the artist's feeling is his law".

[9] To

William Wordsworth, poetry should begin as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings," which the poet then "recollect[s] in tranquility," evoking a new but corresponding emotion the poet can then mould into art.

[10] In order to express these feelings, it was considered that the content of the art needed to come from the imagination of the artist, with as little interference as possible from "artificial" rules dictating what a work should consist of.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge and others believed there were natural laws which the imagination, at least of a good creative artist, would unconsciously follow through

artistic inspiration if left alone to do so.

[11] As well as rules, the influence of models from other works was considered to impede the creator's own imagination, so that

originality was essential. The concept of the

genius, or artist who was able to produce his own original work through this process of "creation from nothingness", is key to Romanticism, and to be derivative was the worst sin.

[12][13][14] This idea is often called "romantic originality."

[15]

Not essential to Romanticism, but so widespread as to be normative, was a strong belief and interest in the importance of nature. However, this is particularly in the effect of nature upon the artist when he is surrounded by it, preferably alone. In contrast to the usually very social art of the

Enlightenment, Romantics were distrustful of the human world, and tended to believe that a close connection with nature was mentally and morally healthy. Romantic art addressed its audiences with what was intended to be felt as the personal voice of the artist. So, in literature, "much of romantic poetry invited the reader to identify the protagonists with the poets themselves".

[16]

According to

Isaiah Berlin, Romanticism embodied "a new and restless spirit, seeking violently to burst through old and cramping forms, a nervous preoccupation with perpetually changing inner states of consciousness, a longing for the unbounded and the indefinable, for perpetual movement and change, an effort to return to the forgotten sources of life, a passionate effort at self-assertion both individual and collective, a search after means of expressing an unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals."

[17]

Etymology

The group of words with the root "Roman" in the various European languages, such as

romance and

Romanesque, has a complicated history, but by the middle of the 18th century "romantic" in English and

romantique in French were both in common use as adjectives of praise for natural phenomena such as views and sunsets, in a sense close to modern English usage but without the sexual connotation. The application of the term to literature first became common in Germany, where the circle around the Schlegel brothers, critics

August and

Friedrich, began to speak of

romantische Poesie ("romantic poetry") in the 1790s, contrasting it with "classic" but in terms of spirit rather than merely dating. Friedrich Schlegel wrote in his

Dialogue on Poetry (1800), "I seek and find the romantic among the older moderns, in Shakespeare, in Cervantes, in Italian poetry, in that age of chivalry, love and fable, from which the phenomenon and the word itself are derived."

[18] In both French and German the closeness of the adjective to

roman, meaning the fairly new literary form of the

novel, had some effect on the sense of the word in those languages. The use of the word did not become general very quickly, and was probably spread more widely in France by its persistent use by

Madame de Staël in her

De L'Allemagne (1813), recounting her travels in Germany.

[19] In England Wordsworth wrote in a preface to his poems of 1815 of the "romantic harp" and "classic lyre",

[19] but in 1820 Byron could still write, perhaps slightly disingenuously, "I perceive that in Germany, as well as in Italy, there is a great struggle about what they call 'Classical' and 'Romantic', terms which were not subjects of classification in England, at least when I left it four or five years ago".

[20] It is only from the 1820s that Romanticism certainly knew itself by its name, and in 1824 the

Académie française took the wholly ineffective step of issuing a decree condemning it in literature.

[21]

The period

The period typically called Romantic varies greatly between different countries and different artistic media or areas of thought.

Margaret Drabble described it in literature as taking place "roughly between 1770 and 1848",

[22] and few dates much earlier than 1770 will be found. In English literature,

M. H. Abrams placed it between 1789, or 1798, this latter a very typical view, and about 1830, perhaps a little later than some other critics.

[23] In other fields and other countries the period denominated as Romantic can be considerably different; musical Romanticism, for example, is generally regarded as only having ceased as a major artistic force as late as 1910, but in an extreme extension the

Four Last Songs of

Richard Strauss are described stylistically as "Late Romantic" and were composed in 1946–48.

[24] However in most fields the Romantic Period is said to be over by about 1850, or earlier.

The early period of the Romantic Era was a time of war, with the French Revolution (1789–1799) followed by the

Napoleonic Wars until 1815. These wars, along with the political and social turmoil that went along with them, served as the background for Romanticism.

[25] The key generation of French Romantics born between 1795–1805 had, in the words of one of their number,

Alfred de Vigny, been "conceived between battles, attended school to the rolling of drums".

[26]

Context and place in history

The more precise characterization and specific definition of Romanticism has been the subject of debate in the fields of

intellectual history and

literary history throughout the 20th century, without any great measure of consensus emerging. That it was part of the

Counter-Enlightenment, a reaction against the

Age of Enlightenment, is generally accepted. Its relationship to the

French Revolution which began in 1789 in the very early stages of the period, is clearly important, but highly variable depending on geography and individual reactions. Most Romantics can be said to be broadly progressive in their views, but a considerable number always had, or developed, a wide range of conservative views,

[27] and nationalism was in many countries strongly associated with Romanticism, as discussed in detail below.

In philosophy and the history of ideas, Romanticism was seen by Isaiah Berlin as disrupting for over a century the classic Western traditions of rationality and the idea of moral absolutes and agreed values, leading "to something like the melting away of the very notion of objective truth",

[28] and hence not only to nationalism, but also

fascism and

totalitarianism, with a gradual recovery coming only after World War II.

[29] For the Romantics, Berlin says,

in the realm of ethics, politics, aesthetics it was the authenticity and sincerity of the pursuit of inner goals that mattered; this applied equally to individuals and groups — states, nations, movements. This is most evident in the aesthetics of romanticism, where the notion of eternal models, a Platonic vision of ideal beauty, which the artist seeks to convey, however imperfectly, on canvas or in sound, is replaced by a passionate belief in spiritual freedom, individual creativity. The painter, the poet, the composer do not hold up a mirror to nature, however ideal, but invent; they do not imitate (the doctrine of mimesis), but create not merely the means but the goals that they pursue; these goals represent the self-expression of the artist's own unique, inner vision, to set aside which in response to the demands of some "external" voice — church, state, public opinion, family friends, arbiters of taste — is an act of betrayal of what alone justifies their existence for those who are in any sense creative.[30]

Arthur Lovejoy attempted to demonstrate the difficulty of defining Romanticism in his seminal article "On The Discrimination of Romanticisms" in his

Essays in the History of Ideas (1948); some scholars see Romanticism as essentially continuous with the present, some like

Robert Hughes see in it the inaugural moment of

modernity,

[31] and some like

Chateaubriand, '

Novalis' and Samuel Taylor Coleridge see it as the beginning of a tradition of resistance to

Enlightenment rationalism—a 'Counter-Enlightenment'—

[32][33] to be associated most closely with

German Romanticism. An earlier definition comes from

Charles Baudelaire: "Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in the way of feeling."

[34]

The end of the Romantic era is marked in some areas by a new style of

Realism, which affected literature, especially the novel and drama, painting, and even music, through

Verismo opera. This movement was led by France, with

Balzac and

Flaubert in literature and

Courbet in painting;

Stendhal and

Goya were important precursors of Realism in their respective media. However, Romantic styles, now often representing the established and safe style against which Realists rebelled, continued to flourish in many fields for the rest of the century and beyond. In music such works from after about 1850 are referred to by some writers as "Late Romantic" and by others as "Neoromantic" or "Postromantic", but other fields do not usually use these terms; in English literature and painting the convenient term "Victorian" avoids having to characterise the period further.

In northern Europe, the Early Romantic visionary optimism and belief that the world was in the process of great change and improvement had largely vanished, and some art became more conventionally political and polemical as its creators engaged polemically with the world as it was. Elsewhere, including in very different ways the United States and Russia, feelings that great change was underway or just about to come were still possible. Displays of intense emotion in art remained prominent, as did the exotic and historical settings pioneered by the Romantics, but experimentation with form and technique was generally reduced, often replaced with meticulous technique, as in the poems of

Tennyson or many paintings. If not realist, late 19th-century art was often extremely detailed, and pride was taken in adding authentic details in a way that earlier Romantics did not trouble with. Many Romantic ideas about the nature and purpose of art, above all the pre-eminent importance of originality, continued to be important for later generations, and often underlie modern views, despite opposition from theorists.

Romantic literature

In literature, Romanticism found recurrent themes in the evocation or criticism of the past, the cult of "

sensibility" with its emphasis on women and children, the isolation of the artist or narrator, and respect for nature. Furthermore, several romantic authors, such as

Edgar Allan Poe and

Nathaniel Hawthorne, based their writings on the

supernatural/

occult and human

psychology. Romanticism tended to regard satire as something unworthy of serious attention, a prejudice still influential today.

[35]

The precursors of Romanticism in English poetry go back to the middle of the 18th century, including figures such as

Joseph Warton (headmaster at

Winchester College) and his brother

Thomas Warton, professor of Poetry at

Oxford University.

[36] Joseph maintained that invention and imagination were the chief qualities of a poet.

Thomas Chatterton is generally considered to be the first Romantic poet in English.

[37] The Scottish poet

James Macpherson influenced the early development of Romanticism with the international success of his

Ossian cycle of poems published in 1762, inspiring both Goethe and the young

Walter Scott. Both Chatterton and Macpherson's work involved elements of fraud, as what they claimed to be earlier literature that they had discovered or compiled was in fact entirely their own work. The

Gothic novel, beginning with

Horace Walpole's

The Castle of Otranto (1764), was an important precursor of one strain of Romanticism, with a delight in horror and threat, and exotic picturesque settings, matched in Walpole's case by his role in the early

revival of Gothic architecture.

Tristram Shandy, a novel by

Laurence Sterne (1759–67) introduced a whimsical version of the anti-rational

sentimental novel to the English literary public.

Germany

An early German influence came from

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose 1774 novel

The Sorrows of Young Werther had young men throughout Europe emulating its protagonist, a young artist with a very sensitive and passionate temperament. At that time Germany was a multitude of small separate states, and Goethe's works would have a seminal influence in developing a unifying sense of

nationalism. Another philosophic influence came from the German idealism of

Johann Gottlieb Fichte and

Friedrich Schelling, making

Jena (where Fichte lived, as well as Schelling,

Hegel,

Schiller and the brothers

Schlegel) a center for early

German Romanticism ("Jenaer Romantik"). Important writers were

Ludwig Tieck,

Novalis (

Heinrich von Ofterdingen, 1799),

Heinrich von Kleist and

Friedrich Hölderlin.

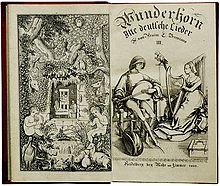

Heidelberg later became a center of German Romanticism, where writers and poets such as

Clemens Brentano,

Achim von Arnim, and

Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff met regularly in literary circles.

Important motifs in German Romanticism are travelling, nature, and

Germanic myths. The later German Romanticism of, for example,

E. T. A. Hoffmann's

Der Sandmann (

The Sandman), 1817, and

Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff's

Das Marmorbild (

The Marble Statue), 1819, was darker in its motifs and has

gothic elements. The significance to Romanticism of childhood innocence, the importance of imagination, and racial theories all combined to give an unprecedented importance to

folk literature, non-classical

mythology and

children's literature, above all in Germany. Brentano and von Arnim were significant literary figures who together published

Des Knaben Wunderhorn ("The Boy's Magic Horn" or

cornucopia), a collection of versified folk tales, in 1806–08. The first collection of

Grimms' Fairy Tales by the

Brothers Grimm was published in 1812.

[38] Unlike the much later work of

Hans Christian Andersen, who was publishing his invented tales in Danish from 1835, these German works were at least mainly based on collected

folk tales, and the Grimms remained true to the style of the telling in their early editions, though later rewriting some parts. One of the brothers,

Jacob, published in 1835

Deutsche Mythologie, a long academic work on Germanic mythology.

[39] Another strain is exemplified by Schiller's highly emotional language and the depiction of physical violence in his play

The Robbers of 1781.

English literature

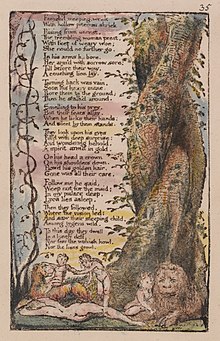

In

English literature, the key figures of the Romantic movement are considered to be the group of poets including

William Wordsworth,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

John Keats,

Lord Byron,

Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the much older

William Blake, followed later by the isolated figure of

John Clare, together with such novelists as

Walter Scott and

Mary Shelley, and the essayists

William Hazlitt and

Charles Lamb. The publication in 1798 of

Lyrical Ballads, with many of the finest poems by Wordsworth and Coleridge, is often held to mark the start of the movement. The majority of the poems were by Wordsworth, and many dealt with the lives of the poor in his native

Lake District, or the poet's feelings about nature, which were to be more fully developed in his long poem

The Prelude, never published in his lifetime. The longest poem in the volume was Coleridge's

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner which showed the Gothic side of English Romanticism, and the exotic settings that many works featured. In the period when they were writing the

Lake Poets were widely regarded as a marginal group of radicals, though they were supported by the critic and writer

William Hazlitt and others.

In contrast

Lord Byron and

Walter Scott achieved enormous fame and influence throughout Europe with works exploiting the violence and drama of their exotic and historical settings; Goethe called Byron "undoubtedly the greatest genius of our century".

[40] Scott achieved immediate success with his long narrative poem

The Lay of the Last Minstrel in 1805, followed by the full

epic poem Marmion in 1808. Both were set in the distant Scottish past, already evoked in

Ossian;

Romanticism and Scotland were to have a long and fruitfiul partnership. Byron had equal success with the first part of

Childe Harold's Pilgrimage in 1812, followed by four "Turkish tales", all in the form of long poems, starting with

The Giaour in 1813, drawing from his

Grand Tour which had reached Ottoman Europe, and

orientalizing the themes of the Gothic novel in verse. These featured different variations of the "

Byronic hero", and his own life contributed a further version. Scott meanwhile was effectively inventing the

historical novel, beginning in 1814 with

Waverley, set in the 1745

Jacobite Rising, which was an enormous and highly profitable success, followed by over 20 further

Waverley Novels over the next 17 years, with settings going back to the

Crusades that he had researched to a degree that was new in literature.

[41]

In contrast to Germany, Romanticism in English literature had little connection with nationalism, and the Romantics were often regarded with suspicion for the sympathy many felt for the ideals of the

French Revolution, whose collapse and replacement with the dictatorship of Napoleon was, as elsewhere in Europe, a shock to the movement. Though his novels celebrated Scottish identity and history, Scott was politically a firm Unionist. Several spent much time abroad, and a famous stay on

Lake Geneva with Byron and Shelley in 1816 produced the hugely influential novel

Frankenstein by Shelley's wife-to-be

Mary Shelley and the

novella The Vampyre by Byron's doctor

John William Polidori. The lyrics of

Robert Burns in Scotland and

Thomas Moore, from Ireland but based in London or elsewhere reflected in different ways their countries and the Romantic interest in folk literature, but neither had a fully Romantic approach to life or their work.

Though they have modern critical champions such as

Georg Lukács, Scott's novels are today more likely to be experienced in the form of the many operas that continued to be based on them over the following decades, such as

Donizetti's

Lucia di Lammermoor and

Vincenzo Bellini's

I puritani (both 1835). Byron is now most highly regarded for his short lyrics and his generally unromantic prose writings, especially his letters, and his unfinished

satire Don Juan.

[42] Unlike many Romantics, Byron's widely-publicised personal life appeared to match his work, and his death at 36 in 1824 from disease when helping the

Greek War of Independence appeared from a distance to be a suitably Romantic end, entrenching his legend.

[43] Keats in 1821 and Shelley in 1822 both died in Italy, Blake (at almost 70) in 1827, and Coleridge largely ceased to write in the 1820s. Wordsworth was by 1820 respectable and highly regarded, holding a government

sinecure, but wrote relatively little. In the discussion of English literature, the Romantic period is often regarded as finishing around the 1820s, or sometimes even earlier, although many authors of the succeeding decades were no less committed to Romantic values.

The most significant novelist in English during the peak Romantic period, other than Walter Scott, was

Jane Austen, whose essentially conservative world-view had little in common with her Romantic contemporaries, retaining a strong belief in decorum and social rules, though critics have detected tremors under the surface of some works, especially

Mansfield Park (1814) and

Persuasion (1817).

[44] But around the mid-century the undoubtedly Romantic novels of the

Yorkshire-based

Brontë family appeared, in particular

Charlotte's Jane Eyre and

Emily's Wuthering Heights, which were both published in 1847.

Byron, Keats and Shelley all wrote for the stage, but with little success in England, with Shelley's

The Cenci perhaps the best work produced, though that was not played in a public theatre in England until a century after his death. Byron's plays, along with dramatisations of his poems and Scott's novels, were much more popular on the Continent, and especially in France, and through these versions several were turned into operas, many still performed today. If contemporary poets had little success on the stage, the period was a legendary one for performances of

Shakespeare, and went some way to restoring his original texts and removing the Augustan "improvements" to them. The greatest actor of the period,

Edmund Kean, restored the tragic ending to

King Lear;

[45] Coleridge said that, “Seeing him act was like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.”

[46]

France

Romanticism was relatively late in developing

in French literature, even more so than in the visual arts. The 18th century precursor to Romanticism, the cult of sensibility, had become associated with the

Ancien regime, and the French Revolution had been more of an inspiration to foreign writers than those experiencing it at first hand. The first major figure was

François-René de Chateaubriand, a minor aristocrat who had remained a royalist throughout the Revolution, and returned to France from exile in England and America under Napoleon, with whose regime he had an uneasy relationship. His writings, all in prose, included some fiction, such as his influential

novella of exile

René (1802), which anticipated Byron in its alienated hero, but mostly contemporary history and politics, his travels, a defence of religion and the medieval spirit (

Génie du christianisme 1802), and finally in the 1830s and 1840s his enormous

autobiography Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe ("Memoirs from beyond the grave").

[47]

The "battle of

Hernani" was fought nightly at the theatre in 1830

After the

Bourbon Restoration, French Romanticism developed in the lively world of

Parisian theatre, with productions of

Shakespeare, Schiller (in France a key Romantic author), and adaptations of Scott and Byron alongside French authors, several of whom began to write in the late 1820s. Cliques of pro- and anti-Romantics developed, and productions were often accompanied by raucous vocalizing by the two sides, including the shouted assertion by one theatregoer in 1822 that "Shakespeare, c'est l'aide-de-camp de Wellington" ("Shakespeare is

Wellington's aide-de-camp").

[48] Alexandre Dumas began as a dramatist, with a series of successes beginning with

Henri III et sa cour (1829) before turning to novels that were mostly historical adventures somewhat in the manner of Scott, most famously

The Three Musketeers and

The Count of Monte Cristo, both of 1844.

Victor Hugo published as a poet in the 1820s before achieving success on the stage with

Hernani, a historical drama in a quasi-Shakespearian style which had famously riotous performances, themselves as much a spectacle as the play, on its first run in 1830.

[49] Like Dumas, he is best known for his novels, and was already writing

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831), one of the best known works of his long career. The preface to his unperformed play "Cromwell" gives an important manifesto of French Romanticism, stating that "there are no rules, or models". The career of

Prosper Mérimée followed a similar pattern; he is now best known as the originator of the story of

Carmen, with his novella of 1845.

Alfred de Vigny remains best known as a dramatist, with his play on the life of the English poet

Chatterton (1835) perhaps his best work.

French Romantic poets of the 1830s to 1850s include

Alfred de Musset,

Gérard de Nerval,

Alphonse de Lamartine and the flamboyant

Théophile Gautier, whose prolific output in various forms continued until his death in 1872.

George Sand took over from

Germaine de Staël as the leading female writer, and was a central figure of the Parisian literary scene, famous both for her novels and criticism and her affairs with

Chopin and several others.

[50]

Stendhal is today probably the most highly regarded French novelist of the period, but he stands in a complex relation with Romanticism, and is notable for his penetrating psychological insight into his characters and his realism, qualities rarely prominent in Romantic fiction. As a survivor of the French

retreat from Moscow in 1812, fantasies of heroism and adventure had little appeal for him, and like Goya he is often seen as a forerunner of Realism. His most important works are

Le Rouge et le Noir (

The Red and the Black, 1830) and

La Chartreuse de Parme (

The Charterhouse of Parma, 1839).

Russia

Early

Russian Romanticism is associated with the writers

Konstantin Batyushkov (

A Vision on the Shores of the Lethe, 1809),

Vasily Zhukovsky (

The Bard, 1811;

Svetlana, 1813) and

Nikolay Karamzin (

Poor Liza, 1792;

Julia, 1796;

Martha the Mayoress, 1802;

The Sensitive and the Cold, 1803). However the principal exponent of Romanticism in Russia is

Alexander Pushkin (

The Prisoner of the Caucasus, 1820–1821;

The Robber Brothers, 1822;

Ruslan and Ludmila, 1820;

Eugene Onegin, 1825–1832). Pushkin's work influenced many writers in the 19th century and led to his eventual recognition as Russia's greatest poet.

[51] Other Russian poets include

Mikhail Lermontov (

A Hero of Our Time, 1839),

Fyodor Tyutchev (

Silentium!, 1830),

Yevgeny Baratynsky (

Eda, 1826),

Anton Delvig, and

Wilhelm Küchelbecker.

Influenced heavily by Lord Byron, Lermontov sought to explore the Romantic emphasis on metaphysical discontent with society and self, while Tyutchev's poems often described scenes of nature or passions of love. Tyutchev commonly operated with such categories as night and day, north and south, dream and reality, cosmos and chaos, and the still world of winter and spring teeming with life. Baratynsky's style was fairly classical in nature, dwelling on the models of the previous century.

Catholic Europe

In predominantly

Roman Catholic countries Romanticism was less pronounced than in Germany and Britain, and developed later, after the rise of

Napoleon;

[citation needed] literary romanticism was strongly interconnected with the national revival of smaller or subjugated nations, and wider cultural romanticism was a prologue to the

revolutions of 1848-1849.

Poland

Romanticism in Poland is often taken to begin with the publication of

Adam Mickiewicz's first poems in 1822, and end with the crushing of the

January Uprising of 1863 against the Russians. It was strongly marked by interest in Polish history.

[52] Polish Romanticism revived the old "Sarmatism" traditions of the

szlachta or Polish nobility. Old traditions and customs were revived and portrayed in a positive light in the Polish messianic movement and in works of great Polish poets such as Adam Mickiewicz (

Pan Tadeusz),

Juliusz Słowacki and

Zygmunt Krasiński, as well as prose writers such as

Henryk Sienkiewicz. This close connection between Polish Romanticism and Polish history became one of the defining qualities of the literature of Polish Romanticism period, differentiating it from that of other countries. They had not suffered the loss of national statehood as was the case with Poland.

[53]

Italy

Romanticism in Italian literature was a minor movement, yet still important; it began officially in 1816 when

Mme de Staël wrote an article in the journal

Biblioteca italiana called "Sulla maniera e l'utilità delle traduzioni", inviting Italian people to reject

Neoclassicism and to study new authors from other countries. Before that date,

Ugo Foscolo had already published poems anticipating Romantic themes. The most important Romantic writers were

Ludovico di Breme, Pietro Borsieri and

Giovanni Berchet. Better known authors such as

Alessandro Manzoni and

Giacomo Leopardi were influenced by

Enlightenment as well as by Romanticism and Classicism.

[54]

Spain

Romanticism in Spanish literature developed a well-known literature with a huge variety of poets and playwrights. The most important Spanish poet during this movement was

José de Espronceda. After him there were other poets like

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer,

Mariano José de Larra and the dramatist

José Zorrilla, author of

Don Juan Tenorio. Before them may be mentioned the pre-romantics

José Cadalso and

Manuel José Quintana.

[55] The plays of

Antonio García Gutiérrez were adapted to produce Giuseppe Verdi's operas

Il trovatore and

Simon Boccanegra. Spanish Romanticism also influenced regional literatures. For example, in

Catalonia and in

Galicia there was a national boom of writers in the local languages, like the Catalan

Jacint Verdaguer and the Galician

Rosalía de Castro, the main figures of the

national revivalist movements

Renaixença and

Rexurdimento, respectively.

[56]

Portugal

Modern Portuguese poetry develops its character from the work of its Romantic epitome,

Almeida Garrett, a very prolific writer who helped shape the genre with the masterpiece

Folhas Caídas (1853). This late arrival of a truly personal Romantic style would linger on to the beginning of the 20th century, notably through the works of poets such as

Alexandre Herculano,

Cesário Verde and

António Nobre. However, an early Portuguese expression of Romanticism is found already in

Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage, especially in his sonnets dated at the end of the 18th century.

South America

A print exemplifying the contrast between neoclassical vs. romantic styles of landscape and architecture (or the "Grecian" and the "Gothic" as they are termed here), 1816.

South American Romanticism was influenced heavily by

Esteban Echeverría, who wrote in the 1830 and 1840s. His writings were influenced by his hatred for the Argentine dictator

Juan Manuel de Rosas, and filled with themes of blood and terror, using the metaphor of a slaughterhouse to portray the violence of Rosas' dictatorship.

Brazilian Romanticism is characterized and divided in three different periods. The first one is basically focused on the creation of a sense of national identity, using the ideal of the heroic Indian. Some examples include

José de Alencar, who wrote "Iracema" and "O Guarani", and

Gonçalves Dias, renowned by the poem "Canção do Exílio" (Song of the Exile). The second period, sometimes called

Ultra-Romanticism, is marked by a profound influence of European themes and traditions, involving the melancholy, sadness and despair related to unobtainable love. Goethe and Lord Byron are commonly quoted in these works. The third cycle is marked by social poetry, especially the abolitionist movement; the greatest writer of this period is

Castro Alves.

[57]

North America

In the United States, at least by 1818 with William Cullen Bryant's "

To a Waterfowl", Romantic poetry was being published. American Romantic

Gothic literature made an early appearance with

Washington Irving's

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) and

Rip Van Winkle (1819), followed from 1823 onwards by the

Leatherstocking Tales of

James Fenimore Cooper, with their emphasis on heroic simplicity and their fervent landscape descriptions of an already-exotic mythicized frontier peopled by "

noble savages", similar to the philosophical theory of

Rousseau, exemplified by

Uncas, from

The Last of the Mohicans. There are picturesque "local color" elements in Washington Irving's essays and especially his travel books.

Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre and his balladic poetry were more influential in France than at home, but the romantic American novel developed fully with the atmosphere and

melodrama of

Nathaniel Hawthorne's

The Scarlet Letter (1850). Later

Transcendentalist writers such as

Henry David Thoreau and

Ralph Waldo Emerson still show elements of its influence and imagination, as does the romantic realism of

Walt Whitman. The poetry of

Emily Dickinson—nearly unread in her own time—and

Herman Melville's novel

Moby-Dick can be taken as epitomes of American Romantic literature. By the 1880s, however, psychological and

social realism were competing with Romanticism in the novel.

Influence of European Romanticism on American writers

The European Romantic movement reached America in the early 19th century. American Romanticism was just as multifaceted and individualistic as it was in Europe. Like the Europeans, the American Romantics demonstrated a high level of moral enthusiasm, commitment to individualism and the unfolding of the self, an emphasis on intuitive perception, and the assumption that the natural world was inherently good, while human society was filled with corruption.

[58]

Romanticism became popular in American politics, philosophy and art. The movement appealed to the revolutionary spirit of America as well as to those longing to break free of the strict religious traditions of early settlement. The Romantics rejected rationalism and religious intellect. It appealed to those in opposition of Calvinism, which includes the belief that the destiny of each individual is preordained. The Romantic movement gave rise to New England

Transcendentalism which portrayed a less restrictive relationship between God and Universe. The new philosophy presented the individual with a more personal relationship with God. Transcendentalism and Romanticism appealed to Americans in a similar fashion, for both privileged feeling over reason, individual freedom of expression over the restraints of tradition and custom. It often involved a rapturous response to nature. It encouraged the rejection of harsh, rigid Calvinism, and promised a new blossoming of American culture.

[58][59]

American Romanticism embraced the individual and rebelled against the confinement of neoclassicism and religious tradition. The Romantic movement in America created a new literary genre that continues to influence American writers. Novels, short stories, and poems replaced the sermons and manifestos of yore. Romantic literature was personal, intense, and portrayed more emotion than ever seen in neoclassical literature. America's preoccupation with freedom became a great source of motivation for Romantic writers as many were delighted in free expression and emotion without so much fear of ridicule and controversy. They also put more effort into the psychological development of their characters, and the main characters typically displayed extremes of sensitivity and excitement.

[60]

The works of the Romantic Era also differed from preceding works in that they spoke to a wider audience, partly reflecting the greater distribution of books as costs came down during the period.

[25] The Romantic period saw an increase in female authors and also female readers.

Romantic visual arts

Thomas Jones,

The Bard, 1774, a prophetic combination of Romanticism and nationalism by the Welsh artist.

In the visual arts, Romanticism first showed itself in

landscape painting, where from as early as the 1760s British artists began to turn to wilder landscapes and storms, and

Gothic architecture, even if they had to make do with

Wales as a setting.

Caspar David Friedrich and

J. M. W. Turner were born less than a year apart in 1774 and 1775 respectively and were to take German and English landscape painting to their extremes of Romanticism, but both were formed when forms of Romanticism was already strongly present in art.

John Constable, born in 1776, stayed closer to the English landscape tradition, but in his largest "six-footers" insisted on the heroic status of a patch of the working countryside where he had grown up, a challenge to the traditional

hierarchy of genres which relegated landscape painting to a low status. Turner also painted very large landscapes, and above all seascapes, some with contemporary settings and

staffage, but others with small figures turning the work into a

history painting in the manner of

Claude Lorrain, like

Salvator Rosa a late Baroque artist whose landscapes had elements that Romantic painters turned to again and again. Friedrich made repeated use of single figures, or features like crosses, set alone amidst a huge landscape, "making them images of the transitoriness of human life and the premonition of death".

[61]

Other groups of artists expressed feelings that verged on the mystical, many largely abandoning classical drawing and proportions. These included

William Blake and

Samuel Palmer and the other members of

the Ancients in England, and in Germany

Philipp Otto Runge. Like Friedrich, none of these artists had significant influence after their deaths for the rest of the 19th century, and were 20th century rediscoveries from obscurity, though Blake was always known as a poet, and

Norway's leading painter

Johan Christian Dahl was heavily influenced by Friedrich. The Rome-based

Nazarene movement of German artists, active from 1810, took a very different path, concentrating on medievalizing history paintings with religious and nationalist themes.

[62]

The arrival of Romanticism in French art was delayed by the strong hold of

Neoclassicism on the academies, but from the

Napoleonic period it became increasingly popular, initially in the form of history paintings propagandising for the new regime, of which

Girodet's

Ossian receiving the Ghosts of the French Heroes, for Napoleon's

Château de Malmaison, was one of the earliest. Girodet's old teacher

David was puzzled and disappointed by his pupil's direction, saying: "Either Girodet is mad or I no longer know anything of the art of painting".

[63] A new generation of the French school,

[64] developed personal Romantic styles, though still concentrating on history painting with a political message.

Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) had his first success with

The Charging Chasseur, a heroic military figure derived from

Rubens, at the

Paris Salon of 1812 in the years of the Empire, but his next major completed work,

The Raft of the Medusa of 1821, remains the greatest achievement of the Romantic history painting, which in its day had a powerful anti-government message.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) made his first Salon hits with

The Barque of Dante (1822),

The Massacre at Chios (1824) and

Death of Sardanapalus (1827). The second was a scene from the Greek War of Independence, completed the year Byron died there, and the last was a scene from one of Byron's plays. With Shakespeare, Byron was to provide the subject matter for many other works of Delacroix, who also spent long periods in North Africa, painting colourful scenes of mounted Arab warriors. His

Liberty Leading the People (1830) remains, with the

Medusa, one of the best known works of French Romantic painting. Both reflected current events, and increasingly "

history painting", literally "story painting", a phrase dating back to the Italian Renaissance meaning the painting of subjects with groups of figures, long considered the highest and most difficult form of art, did indeed become the painting of historical scenes, rather than those from religion or mythology.

[65]

Francisco Goya was called "the last great painter in whose art thought and observation were balanced and combined to form a faultless unity".

[66] But the extent to which he was a Romantic is a complex question; in Spain there was still a struggle to introduce the values of the

Enlightenment, in which Goya saw himself as a participant. The demonic and anti-rational monsters thrown up by his imagination are only superficially similar to those of the Gothic fantasies of northern Europe, and in many ways he remained wedded to the classicism and realism of his training, as well as looking forward to the Realism of the later 19th century.

[67] But he, more than any other artist of the period, exemplified the Romantic values of the expression of the artist's feelings and his personal imaginative world.

[68] He also shared with many of the Romantic painters a more free handling of paint, emphasized in the new prominence of the brushstroke and

impasto, which tended to be repressed in neoclassicism under a self-effacing finish.

Sculpture remained largely impervious to Romanticism, probably partly for technical reasons, as the most prestigious material of the day, marble, does not lend itself to expansive gestures. The leading sculptors in Europe,

Antonio Canova and

Bertel Thorvaldsen, were both based in Rome and firm Neoclassicists, not at all tempted to allow influence from medieval sculpture, which would have been one possible approach to Romantic sculpture. When it did develop, true Romantic sculpture, with the exception of a few artists such as

Rudolf Maison[69] rather oddly was missing in Germany, and mainly found in France, with

François Rude, best known from his group of the 1830s from the

Arc de Triomphe in Paris,

David d'Angers and

Auguste Préault, whose plaster relief entitled

Slaughter, which represented the horrors of wars with exacerbated passion, caused so much scandal at the 1834

Salon that Préault was banned from this official annual exhibition for nearly twenty years.

[70] In Italy, the most important Romantic sculptor was

Lorenzo Bartolini.

[71]

In France, historical painting on idealized medieval and Renaissance themes is known as the

style Troubadour, a term which rather lacks equivalents for other countries, though the same trends occurred there. Delacroix,

Ingres and

Richard Parkes Bonington all worked in this style, as did lesser specialists such as

Pierre-Henri Révoil (1776–1842) and

Fleury-François Richard (1777–1852). Their pictures are often small, and feature intimate private and anecdotal moments, as well as those of high drama. The lives of great artists such as

Raphael were commemorated on equal terms with those of rulers, and fictional characters were also depicted. Fleury-Richard's

Valentine of Milan weeping for the death of her husband, shown in the

Paris Salon of 1802, marked the arrival of the style, which lasted until the mid-century, before being subsumed into the increasingly academic history painting of artists like

Paul Delaroche.

[72]

Another trend was for very large apocalyptic history paintings, often combining extreme natural events, or divine wrath, with human disaster, attempting to outdo

The Raft of the Medusa, and now often drawing comparisons with effects from Hollywood. The leading English artist in the style was

John Martin, whose tiny figures were dwarfed by enormous earthquakes and storms, and worked his way through the biblical disasters, and those to come in the

final days. Other works, including Delacroix's

Death of Sardanapalus included larger figures, and these often drew heavily on earlier artists, especially

Poussin and

Rubens, with extra emotionalism and special effects.

Elsewhere in Europe, leading artists adopted Romantic styles: in Russia there were the portraitists

Orest Kiprensky and

Vasily Tropinin, with

Ivan Aivazovsky specializing in

marine painting, and in Norway

Hans Gude painted secenes of

fjords. In Italy

Francesco Hayez (1791–1882) was the leading artist of Romanticism in mid-19th-century

Milan. His long, prolific and extremely successful career saw him begin as a Neoclassical painter, pass right through the Romantic period, and emerge at the other end as a sentimental painter of young women. His Romantic period included many historical pieces of "Troubadour" tendencies, but on a very large scale, that are heavily influenced by

Gian Battista Tiepolo and other late Baroque Italian masters.

Literary Romanticism had its counterpart in the American visual arts, most especially in the exaltation of an untamed American

landscape found in the paintings of the

Hudson River School. Painters like

Thomas Cole,

Albert Bierstadt and

Frederic Edwin Church and others often expressed Romantic themes in their paintings. They sometimes depicted ancient ruins of the old world, such as in Fredric Edwin Church’s piece

Sunrise in Syria. These works reflected the Gothic feelings of death and decay. They also show the Romantic ideal that Nature is powerful and will eventually overcome the transient creations of men. More often, they worked to distinguish themselves from their European counterparts by depicting uniquely American scenes and landscapes. This idea of an American identity in the art world is reflected in

W. C. Bryant’s poem,

To Cole, the Painter, Departing for Europe, where Bryant encourages Cole to remember the powerful scenes that can only be found in America.

Some American paintings promote the literary idea of the “noble savage” (Such as Albert Bierstadt’s

The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Peak) by portraying idealized Native Americans living in harmony with the natural world. Thomas Cole's paintings tend towards

allegory, explicit in

The Voyage of Life series painted in the early 1840s, showing the stages of life set amidst an awesome and immense nature.

-

-

-

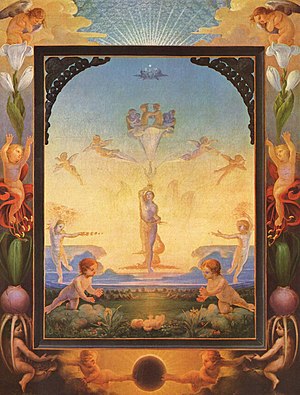

Louis Janmot, from his series "The Poem of the Soul", before 1854

-

Thomas Cole, 1842,

The Voyage of Life

Old Age

Romanticism and music

Musical Romanticism is predominantly a German phenomenon—so much so that one respected French reference work defines it entirely in terms of "The role of music in the aesthetics of German romanticism".

[73] Another French encyclopedia holds that the German temperament generally "can be described as the deep and diverse action of romanticism on German musicians", and that there is only one true representative of Romanticism in French music,

Hector Berlioz, while in Italy, the sole great name of musical Romanticism is

Giuseppe Verdi, "a sort of [Victor] Hugo of opera, gifted with a real genius for dramatic effect". Nevertheless, the huge popularity of German Romantic music led, "whether by imitation or by reaction", to an often nationalistically inspired vogue amongst Polish, Hungarian, Russian, Czech, and Scandinavian musicians, successful "perhaps more because of its extra-musical traits than for the actual value of musical works by its masters".

[74]

Although the term "Romanticism" when applied to music has come to imply the period roughly from 1800 until 1850, or else until around 1900, the contemporary application of "romantic" to music did not coincide with this modern interpretation. Indeed, one of the earliest sustained applications of the term to music occurs in 1789, in the

Mémoires of

André Grétry.

[75] This is of particular interest because it is a French source on a subject mainly dominated by Germans, but also because it explicitly acknowledges its debt to

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (himself a composer, amongst other things) and, by so doing, establishes a link to one of the major influences on the Romantic movement generally.

[76] In 1810

E.T.A. Hoffmann named

Mozart,

Haydn and

Beethoven as "the three masters of instrumental compositions" who "breathe one and the same romantic spirit". He justified his view on the basis of these composers' depth of evocative expression and their marked individuality. In Haydn's music, according to Hoffmann, "a child-like, serene disposition prevails", while Mozart (in the late

E-flat major Symphony, for example) "leads us into the depths of the spiritual world", with elements of fear, love, and sorrow, "a presentiment of the infinite … in the eternal dance of the spheres". Beethoven's music, on the other hand, conveys a sense of "the monstrous and immeasurable", with the pain of an endless longing which "will burst our breasts in a fully coherent concord of all the passions".

[77] This elevation in the valuation of pure emotion resulted in the promotion of music from the subordinate position it had held in relation to the verbal and plastic arts during the Enlightenment. Because music was considered to be free of the constraints of reason, imagery, or any other precise concept, it came to be regarded, first in the writings of

Wackenroder and

Tieck and later by writers such as

Schelling and

Wagner, as preeminent among the arts, the one best able to express the secrets of the universe, to evoke the spirit world, infinity, and the absolute.

[78]

This chronologic agreement of musical and literary Romanticism continued as far as the middle of the 19th century, when

Richard Wagner denigrated the music of

Meyerbeer and

Berlioz as "

neoromantic": "The Opera, to which we shall now return, has swallowed down the Neoromanticism of Berlioz, too, as a plump, fine-flavoured oyster, whose digestion has conferred on it anew a brisk and well-to-do appearance".

[79]

It was only toward the end of the 19th century that the newly emergent discipline of

Musikwissenschaft (

musicology)—itself a product of the historicizing proclivity of the age—attempted a more scientific

periodization of music history, and a distinction between

Viennese Classical and Romantic periods was proposed. The key figure in this trend was

Guido Adler, who viewed Beethoven and

Franz Schubert as transitional but essentially Classical composers, with Romanticism achieving full maturity only in the post-Beethoven generation of

Frédéric Chopin,

Robert Schumann, Berlioz, and

Franz Liszt. From Adler's viewpoint, found in books like

Der Stil in der Musik (1911), composers of the

New German School and various late-19th-century

nationalist composers were not Romantics but "moderns" or "realists" (by analogy with the fields of painting and literature), and this schema remained prevalent through the first decades of the 20th century.

[76]

By the second quarter of the 20th century, an awareness that radical changes in musical syntax had occurred during the early 1900s caused another shift in historical viewpoint, and the change of century came to be seen as marking a decisive break with the musical past. This in turn led historians such as

Alfred Einstein[80] to extend the musical "

Romantic Era" throughout the 19th century and into the first decade of the 20th. It has continued to be referred to as such in some of the standard music references such as

The Oxford Companion to Music[81] and

Grout's History of Western Music[82] but was not unchallenged. For example, the prominent German musicologist

Friedrich Blume, the chief editor of the first edition of

Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (1949–86), accepted the earlier position that Classicism and Romanticism together constitute a single period beginning in the middle of the 18th century, but at the same time held that it continued into the 20th century, including such pre–World War II developments as

expressionism and

neoclassicism.

[83] This is reflected in some notable recent reference works such as the

New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians[76] and the new edition of

Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart.

[84]

In the contemporary music culture, the romantic musician followed a public career depending on sensitive middle-class audiences rather than on a courtly patron, as had been the case with earlier musicians and composers. Public persona characterized a new generation of virtuosi who made their way as soloists, epitomized in the concert tours of

Paganini and

Liszt, and the conductor began to emerge as an important figure, on whose skill the interpretation of the increasingly complex music depended.

[85]

Romanticism outside the arts

Sciences

The Romantic movement affected most aspects of intellectual life, and

Romanticism and science had a powerful connection, especially in the period 1800–40. Many scientists were influenced by versions of the

Naturphilosophie of

Johann Gottlieb Fichte,

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling and

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and others, and without abandoning

empiricism, sought in their work to uncover what they tended to believe was a unified and organic Nature. The English scientist Sir

Humphry Davy, a prominent Romantic thinker, said that understanding nature required “an attitude of admiration, love and worship, […] a personal response.”

[86] He believed that knowledge was only attainable by those who truly appreciated and respected nature. Self-understanding was an important aspect of Romanticism. It had less to do with proving that man was capable of understanding nature (through his budding intellect) and therefore controlling it, and more to do with the emotional appeal of connecting himself with nature and understanding it through a harmonious co-existence.

[87]

Historiography

History writing was very strongly, and many would say harmfully, influenced by Romanticism.

[88] In England

Thomas Carlyle was a highly influential essayist who turned historian; he both invented and exemplified the phrase "hero-worship",

[89] lavishing largely uncritical praise on strong leaders such as

Oliver Cromwell,

Frederick the Great and Napoleon. Romantic nationalism had a largely negative effect on the writing of history in the 19th century, as each nation tended to

produce its own version of history, and the critical attitude, even cynicism, of earlier historians was often replaced by a tendency to create romantic stories with clearly distinguished heroes and villains.

[90] Nationalist ideology of the period placed great emphasis on racial coherence, and the antiquity of peoples, and tended to vastly over-emphasize the continuity between past periods and the present, leading to

national mysticism. Much historical effort in the 20th century was devoted to combating the romantic historical myths created in the 19th century.

Theology

To insulate theology from

reductionism in science, 19th century post-Enlightenment German theologians moved in a new direction, led by

Friedrich Schleiermacher and

Albrecht Ritschl. They took the Romantic approach of rooting religion in the inner world of the human spirit, so that it is a person's feeling or sensibility about spiritual matters that comprises religion.

[91]

Romantic nationalism

One of Romanticism's key ideas and most enduring legacies is the assertion of nationalism, which became a central theme of Romantic art and political philosophy. From the earliest parts of the movement, with their focus on development of national languages and

folklore, and the importance of local customs and traditions, to the movements which would redraw the map of Europe and lead to calls for self-determination of nationalities, nationalism was one of the key vehicles of Romanticism, its role, expression and meaning. One of the most important functions of medieval references in the 19th century was nationalist. Popular and epic poetry were its workhorses. This is visible in Germany and Ireland, where underlying Germanic or Celtic substrates dating from before the Romanisation-Latinisation were sought out. And, in Catalonia, which reclaimed Catalanism from before the Hispanicization of the Catholic Monarchs in the 15th century, when the Crown of Aragon was unified with the Castilian nobility.

[citation needed]

Early Romantic nationalism was strongly inspired by

Rousseau, and by the ideas of

Johann Gottfried von Herder, who in 1784 argued that the geography formed the natural economy of a people, and shaped their customs and society.

[citation needed]

The nature of nationalism changed dramatically, however, after the

French Revolution with the rise of

Napoleon, and the reactions in other nations. Napoleonic nationalism and republicanism were, at first, inspirational to movements in other nations: self-determination and a consciousness of national unity were held to be two of the reasons why France was able to defeat other countries in battle. But as the

French Republic became

Napoleon's Empire, Napoleon became not the inspiration for nationalism, but the object of its struggle. In

Prussia, the development of spiritual renewal as a means to engage in

the struggle against Napoleon was argued by, among others,

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a disciple of

Kant. The word

Volkstum, or nationality, was coined in German as part of this resistance to the now conquering emperor. Fichte expressed the unity of language and nation in his address "To the German Nation" in 1806:

Those who speak the same language are joined to each other by a multitude of invisible bonds by nature herself, long before any human art begins; they understand each other and have the power of continuing to make themselves understood more and more clearly; they belong together and are by nature one and an inseparable whole. ...Only when each people, left to itself, develops and forms itself in accordance with its own peculiar quality, and only when in every people each individual develops himself in accordance with that common quality, as well as in accordance with his own peculiar quality—then, and then only, does the manifestation of divinity appear in its true mirror as it ought to be.[92]

This view of nationalism inspired the collection of

folklore by such people as the

Brothers Grimm, the revival of old epics as national, and the construction of new epics as if they were old, as in the

Kalevala, compiled from Finnish tales and folklore, or

Ossian, where the claimed ancient roots were invented. The view that fairy tales, unless contaminated from outside literary sources, were preserved in the same form over thousands of years, was not exclusive to Romantic Nationalists, but fit in well with their views that such tales expressed the primordial nature of a people. For instance, the Brothers Grimm rejected many tales they collected because of their similarity to tales by

Charles Perrault, which they thought proved they were not truly German tales;

[93] Sleeping Beauty survived in their collection because the tale of

Brynhildr convinced them that the figure of the sleeping princess was authentically German.

Romanticism played an essential role in the national awakening of many Central European peoples lacking their own national states, not least in

Poland, which had recently lost its independence when Russia's army crushed the

Polish Uprising under

Nicholas I. Revival and reinterpretation of ancient myths, customs and traditions by Romantic poets and painters helped to distinguish their indigenous cultures from those of the dominant nations and crystallise the mythography of

Romantic nationalism. Patriotism, nationalism, revolution and armed struggle for independence also became popular themes in the arts of this period. Arguably, the most distinguished Romantic poet of this part of Europe was

Adam Mickiewicz, who developed an idea that

Poland was the Messiah of Nations, predestined to suffer just as

Jesus had suffered to save all the people.

[citation needed]

Gallery

- Emerging Romanticism in the 18th century

- French Romantic painting

- other

-

Joseph Anton Koch,

Waterfalls at Subiaco 1812–1813, a "classical" landscape to art historians

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Romantic authors

Scholars of Romanticism