From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Yellowstone National Park is a

national park located in the

U.S. states of

Wyoming,

Montana, and

Idaho. It was established by the

U.S. Congress and signed into law by President

Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872.

[4][5] Yellowstone was the first National Park in the U.S. and is also widely held to be the first national park in the world.

[6] The park is known for its wildlife and its many

geothermal features, especially

Old Faithful Geyser, one of its most popular features.

[7] It has many types of

ecosystems, but the

subalpine forest is the most abundant. It is part of the

South Central Rockies forests ecoregion.

Native Americans have lived in the Yellowstone region for at least 11,000 years.

[8] Aside from visits by

mountain men

during the early-to-mid-19th century, organized exploration did not

begin until the late 1860s. Management and control of the park

originally fell under the jurisdiction of the

Secretary of the Interior, the first being

Columbus Delano. However, the

U.S. Army was subsequently commissioned to oversee management of Yellowstone for a 30-year period between 1886 and 1916.

[9] In 1917, administration of the park was transferred to the

National Park Service,

which had been created the previous year. Hundreds of structures have

been built and are protected for their architectural and historical

significance, and researchers have examined more than 1,000

archaeological sites.

Yellowstone National Park spans an area of 3,468.4 square miles (8,983 km

2),

[1] comprising lakes, canyons, rivers and

mountain ranges.

[7] Yellowstone Lake is one of the largest high-elevation lakes in North America and is centered over the

Yellowstone Caldera, the largest

supervolcano on the continent. The

caldera is considered an active volcano. It has erupted with tremendous force several times in the last two million years.

[10] Half of the world's geothermal features are in Yellowstone, fueled by this ongoing volcanism.

[11] Lava flows and rocks from volcanic eruptions cover most of the land area of Yellowstone. The park is the centerpiece of the

Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the largest remaining nearly-intact ecosystem in the Earth's northern temperate zone.

[12]

Hundreds of species of mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles have been documented, including several that are either

endangered or

threatened.

[7] The vast forests and grasslands also include unique species of plants. Yellowstone Park is the largest and most famous

megafauna location in the

Continental United States.

Grizzly bears,

wolves, and free-ranging herds of

bison and

elk live in the park. The

Yellowstone Park bison herd is the oldest and largest public bison herd in the United States.

Forest fires occur in the park each year; in the

large forest fires of 1988, nearly one third of the park was burnt. Yellowstone has numerous recreational opportunities, including hiking,

camping,

boating,

fishing and sightseeing. Paved roads provide close access to the major

geothermal areas as well as some of the lakes and waterfalls. During the

winter, visitors often access the park by way of guided tours that use

either

snow coaches or

snowmobiles.

History

Detailed pictorial map from 1904

Share of the Yellowstone Park Association, issued 10 May 1889

The park contains the headwaters of the

Yellowstone River, from which it takes its historical name. Near the end of the 18th century,

French trappers named the river

Roche Jaune, which is probably a translation of the

Hidatsa name

Mi tsi a-da-zi ("Rock Yellow River").

[13]

Later, American trappers rendered the French name in English as "Yellow

Stone". Although it is commonly believed that the river was named for

the yellow rocks seen in the

Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Native American name source is unclear.

[14]

The human history of the park begins at least 11,000 years ago when

Native Americans began to hunt and fish in the region. During the

construction of the post office in

Gardiner, Montana, in the 1950s, an

obsidian projectile point of

Clovis origin was found that dated from approximately 11,000 years ago.

[15] These

Paleo-Indians, of the Clovis culture, used the significant amounts of obsidian found in the park to make

cutting tools and

weapons.

Arrowheads made of Yellowstone obsidian have been found as far away as the

Mississippi Valley, indicating that a regular obsidian trade existed between local tribes and tribes farther east.

[16] By the time

white explorers first entered the region during the

Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805, they encountered the

Nez Perce,

Crow, and

Shoshone

tribes. While passing through present day Montana, the expedition

members heard of the Yellowstone region to the south, but they did not

investigate it.

[16]

In 1806,

John Colter, a member of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition,

left to join a group of fur trappers. After splitting up with the other

trappers in 1807, Colter passed through a portion of what later became

the park, during the winter of 1807–1808. He observed at least one

geothermal area in the northeastern section of the park, near

Tower Fall.

[17] After surviving wounds he suffered in a battle with members of the Crow and

Blackfoot tribes in 1809, Colter described a place of "

fire and brimstone" that most people dismissed as delirium; the supposedly imaginary place was nicknamed "

Colter's Hell". Over the next 40 years, numerous reports from mountain men and trappers told of boiling mud, steaming rivers, and

petrified trees, yet most of these reports were believed at the time to be myth.

[18]

After an 1856 exploration, mountain man

Jim Bridger (also believed to be the first or second European American to have seen the

Great Salt Lake)

reported observing boiling springs, spouting water, and a mountain of

glass and yellow rock. These reports were largely ignored because

Bridger was a known "spinner of yarns". In 1859, a U.S. Army Surveyor

named Captain

William F. Raynolds embarked on a

two-year survey of the northern Rockies. After wintering in Wyoming, in May 1860, Raynolds and his party – which included naturalist

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden and guide Jim Bridger – attempted to cross the

Continental Divide over

Two Ocean Plateau from the

Wind River

drainage in northwest Wyoming. Heavy spring snows prevented their

passage, but had they been able to traverse the divide, the party would

have been the first organized survey to enter the Yellowstone region.

[19] The

American Civil War hampered further organized explorations until the late 1860s.

[20]

Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829–1887) American geologist who convinced Congress to make Yellowstone a National Park in 1872.

The first detailed expedition to the Yellowstone area was the

Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition

of 1869, which consisted of three privately funded explorers. The

Folsom party followed the Yellowstone River to Yellowstone Lake.

[21]

The members of the Folsom party kept a journal and based on the

information it reported, a party of Montana residents organized the

Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition in 1870. It was headed by the surveyor-general of Montana

Henry Washburn, and included

Nathaniel P. Langford (who later became known as "National Park" Langford) and a U.S. Army detachment commanded by Lt.

Gustavus Doane.

The expedition spent about a month exploring the region, collecting

specimens and naming sites of interest. A Montana writer and lawyer

named Cornelius Hedges, who had been a member of the Washburn

expedition, proposed that the region should be set aside and protected

as a national park; he wrote detailed articles about his observations

for the

Helena Herald newspaper between 1870 and 1871. Hedges

essentially restated comments made in October 1865 by acting Montana

Territorial Governor

Thomas Francis Meagher, who had previously commented that the region should be protected.

[22] Others made similar suggestions. In an 1871 letter from

Jay Cooke to Ferdinand V. Hayden, Cooke wrote that his friend, Congressman

William D. Kelley had also suggested "

Congress pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever".

[23]

Park creation

Ferdinand V. Hayden's map of Yellowstone National Park, 1871

In 1871, eleven years after his failed first effort,

Ferdinand V. Hayden

was finally able to explore the region. With government sponsorship, he

returned to the region with a second, larger expedition, the

Hayden Geological Survey of 1871. He compiled a comprehensive report, including large-format photographs by

William Henry Jackson and paintings by

Thomas Moran. The report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from

public auction. On March 1, 1872, President

Ulysses S. Grant signed

The Act of Dedication[5] law that created Yellowstone National Park.

[24]

Hayden, while not the only person to have thought of creating a park

in the region, was its first and most enthusiastic advocate.

[25]

He believed in "setting aside the area as a pleasure ground for the

benefit and enjoyment of the people" and warned that there were those

who would come and "make merchandise of these beautiful specimens".

[25] Worrying the area could face the same fate as

Niagara Falls, he concluded the site should "be as free as the air or Water."

[25]

In his report to the Committee on Public Lands, he concluded that if

the bill failed to become law, "the vandals who are now waiting to enter

into this wonder-land, will in a single season despoil, beyond

recovery, these remarkable curiosities, which have required all the

cunning skill of nature thousands of years to prepare".

[26][27]

Hayden and his 1871 party recognized Yellowstone as a priceless

treasure that would become rarer with time. He wished for others to see

and experience it as well. Eventually the railroads and, some time after

that, the automobile would make that possible. The Park was not set

aside strictly for ecological purposes; however, the designation

"pleasure ground" was not an invitation to create an amusement park.

Hayden imagined something akin to the scenic resorts and baths in

England, Germany, and Switzerland.

[25]

THE ACT OF DEDICATION[27]

AN ACT to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the

headwaters of the Yellowstone River as a public park. Be it enacted by

the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America

in Congress assembled, That the tract of land in the Territories of

Montana and Wyoming ... is hereby reserved and withdrawn from

settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and

dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground for the

benefit and enjoyment of the people; and all persons who shall locate,

or settle upon, or occupy the same or any part thereof, except as

hereinafter provided, shall be considered trespassers and removed there

from ...

Approved March 1, 1872.

Signed by:

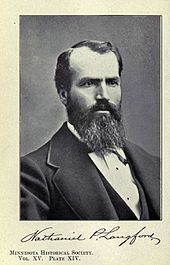

(1870) Portrait of Nathaniel P. Langford, the first superintendent of the park

[28]

There was considerable local opposition to the Yellowstone National

Park during its early years. Some of the locals feared that the regional

economy would be unable to thrive if there remained strict federal

prohibitions against resource development or settlement within park

boundaries and local entrepreneurs advocated reducing the size of the

park so that mining, hunting, and logging activities could be developed.

[29]

To this end, numerous bills were introduced into Congress by Montana

representatives who sought to remove the federal land-use restrictions.

[30]

After the park's official formation, Nathaniel Langford was appointed

as the park's first superintendent in 1872 by Secretary of Interior

Columbus Delano.

Langford served for five years but was denied a salary, funding, and

staff. Langford lacked the means to improve the land or properly protect

the park, and without formal policy or regulations, he had few legal

methods to enforce such protection. This left Yellowstone vulnerable to

poachers, vandals, and others seeking to raid its resources. He

addressed the practical problems park administrators faced in the 1872

Report to the Secretary of the Interior

[31]

and correctly predicted that Yellowstone would become a major

international attraction deserving the continuing stewardship of the

government. In 1874, both Langford and Delano advocated the creation of a

federal agency to protect the vast park, but Congress refused. In 1875,

Colonel

William Ludlow, who had previously explored areas of Montana under the command of

George Armstrong Custer,

was assigned to organize and lead an expedition to Montana and the

newly established Yellowstone Park. Observations about the lawlessness

and exploitation of park resources were included in Ludlow's

Report of a Reconnaissance to the Yellowstone National Park. The report included letters and attachments by other expedition members, including naturalist and mineralogist

George Bird Grinnell.

Great Falls of the Yellowstone", U.S. Geological and Geographic Survey

of the Territories (1874–1879) Photographer: William Henry Jackson

Grinnell documented the poaching of buffalo, deer, elk, and antelope

for hides. "It is estimated that during the winter of 1874–1875, not

less than 3,000 buffalo and mule deer suffer even more severely than the

elk, and the antelope nearly as much."

[32]

As a result, Langford was forced to step down in 1877.

[33][34] Having traveled through Yellowstone and witnessed land management problems first hand,

Philetus Norris

volunteered for the position following Langford's exit. Congress

finally saw fit to implement a salary for the position, as well as to

provide a minimal funding to operate the park. Norris used these funds

to expand access to the park, building numerous crude roads and

facilities.

[34]

In 1880,

Harry Yount

was appointed as a gamekeeper to control poaching and vandalism in the

park. Yount had previously spent decades exploring the mountain country

of present-day Wyoming, including the

Grand Tetons, after joining

F V. Hayden's Geological Survey in 1873.

[35] Yount is the first national park ranger,

[36] and Yount's Peak, at the head of the Yellowstone River, was named in his honor.

[37]

However, these measures still proved to be insufficient in protecting

the park, as neither Norris, nor the three superintendents who followed,

were given sufficient manpower or resources.

Fort Yellowstone, formerly a U.S. Army post, now serves as park headquarters.

The

Northern Pacific Railroad built a train station in

Livingston, Montana, connecting to the northern entrance in the early 1880s, which helped to increase visitation from 300 in 1872 to 5,000 in 1883.

[38] Visitors in these early years faced poor roads and limited services, and most access into the park was on horse or via

stagecoach. By 1908 visitation increased enough to attract a

Union Pacific Railroad connection to West Yellowstone, though rail visitation fell off considerably by

World War II

and ceased around the 1960s. Much of the railroad line was converted to

nature trails, among them the Yellowstone Branch Line Trail.

Thomas Moran painted Tower Creek, Yellowstone, while on the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871

During the 1870s and 1880s Native American tribes were effectively

excluded from the national park. Under a half-dozen tribes had made

seasonal use of the Yellowstone area, but the only year-round residents

were small bands of

Eastern Shoshone known as "

Sheepeaters".

They left the area under the assurances of a treaty negotiated in 1868,

under which the Sheepeaters ceded their lands but retained the right to

hunt in Yellowstone. The United States never ratified the treaty and

refused to recognize the claims of the Sheepeaters or any other tribe

that had used Yellowstone.

[39]

The

Nez Perce band associated with

Chief Joseph,

numbering about 750 people, passed through Yellowstone National Park in

thirteen days during late August 1877. They were being pursued by the

U.S. Army and entered the national park about two weeks after the

Battle of the Big Hole.

Some of the Nez Perce were friendly to the tourists and other people

they encountered in the park; some were not. Nine park visitors were

briefly taken captive. Despite Joseph and other chiefs ordering that no

one should be harmed, at least two people were killed and several

wounded.

[40][41] One of the areas where encounters occurred was in Lower Geyser Basin and east along a branch of the

Firehole River to Mary Mountain and beyond.

[40] That stream is still known as Nez Perce Creek.

[42] A group of

Bannocks entered the park in 1878, alarming park Superintendent

Philetus Norris. In the aftermath of the

Sheepeater Indian War of 1879, Norris built a fort to prevent Native Americans from entering the national park.

[39][41]

Ongoing poaching and destruction of natural resources continued unabated until the U.S. Army arrived at

Mammoth Hot Springs

in 1886 and built Camp Sheridan. Over the next 22 years the army

constructed permanent structures, and Camp Sheridan was renamed

Fort Yellowstone.

[43] On May 7, 1894, the

Boone and Crockett Club, acting through the personality of George G. Vest, Arnold Hague, William Hallett Phillips, W. A. Wadsworth, Archibald Rogers,

Theodore Roosevelt, and

George Bird Grinnell were successful in carrying through the Park Protection Act, which so saved the Park.

[44]

The Lacey Act of 1900 provided legal support for the officials

prosecuting poachers. With the funding and manpower necessary to keep a

diligent watch, the army developed their own policies and regulations

that permitted public access while protecting park wildlife and natural

resources. When the National Park Service was created in 1916, many of

the management principles developed by the army were adopted by the new

agency.

[43] The army turned control over to the National Park Service on October 31, 1918.

[45]

In 1898, the naturalist

John Muir

described the park as follows: "However orderly your excursions or

aimless, again and again amid the calmest, stillest scenery you will be

brought to a standstill hushed and awe-stricken before phenomena wholly

new to you. Boiling springs and huge deep pools of purest green and

azure water, thousands of them, are plashing and heaving in these high,

cool mountains as if a fierce furnace fire were burning beneath each one

of them; and a hundred geysers, white torrents of boiling water and

steam, like inverted waterfalls, are ever and anon rushing up out of the

hot, black underworld."

[46]

Later history

Park Superintendent Horace M. Albright and dinner guests, 1922. The

feeding of "tame" black bears was popular with tourists in the early

days of the park, but led to 527 injuries between 1931 and 1939.

[47]

By 1915, 1,000 automobiles per year were entering the park, resulting

in conflicts with horses and horse-drawn transportation. Horse travel

on roads was eventually prohibited.

[48]

The

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a

New Deal

relief agency for young men, played a major role between 1933 and 1942

in developing Yellowstone facilities. CCC projects included

reforestation, campground development of many of the park's trails and

campgrounds, trail construction, fire hazard reduction, and

fire-fighting work. The CCC built the majority of the early visitor

centers, campgrounds and the current system of park roads.

[49]

During

World War II, tourist travel fell sharply, staffing was cut, and many facilities fell into disrepair.

[50]

By the 1950s, visitation increased tremendously in Yellowstone and

other national parks. To accommodate the increased visitation, park

officials implemented

Mission 66,

an effort to modernize and expand park service facilities. Planned to

be completed by 1966, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the founding

of the National Park Service, Mission 66 construction diverged from the

traditional log cabin style with design features of a modern style.

[51]

During the late 1980s, most construction styles in Yellowstone reverted

to the more traditional designs. After the enormous forest fires of

1988 damaged much of Grant Village, structures there were rebuilt in the

traditional style. The visitor center at Canyon Village, which opened

in 2006, incorporates a more traditional design as well.

[52]

The

Roosevelt Arch is located in Gardiner, Montana at the North Entrance

The

1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake just west of Yellowstone at

Hebgen Lake

damaged roads and some structures in the park. In the northwest section

of the park, new geysers were found, and many existing hot springs

became turbid.

[53] It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the region in recorded history.

In 1963, after several years of public controversy regarding the

forced reduction of the elk population in Yellowstone, United States

Secretary of the Interior

Stewart Udall

appointed an advisory board to collect scientific data to inform future

wildlife management of the national parks. In a paper known as the

Leopold Report,

the committee observed that culling programs at other national parks

had been ineffective, and recommended management of Yellowstone's elk

population.

[54]

The

wildfires

during the summer of 1988 were the largest in the history of the park.

Approximately 793,880 acres (321,272 ha; 1,240 sq mi) or 36% of the

parkland was impacted by the fires, leading to a systematic

re-evaluation of fire management policies. The fire season of 1988 was

considered normal until a combination of drought and heat by mid-July

contributed to an extreme fire danger. On "Black Saturday", August 20,

1988, strong winds expanded the fires rapidly, and more than 150,000

acres (61,000 ha; 230 sq mi) burned.

[55]

The expansive cultural history of the park has been documented by the 1,000

archeological sites that have been discovered. The park has 1,106

historic structures and features, and of these

Obsidian Cliff and five buildings have been designated

National Historic Landmarks.

[7] Yellowstone was designated an

International Biosphere Reserve on October 26, 1976, and a UN

World Heritage Site on September 8, 1978. The park was placed on the

List of World Heritage in Danger from 1995 to 2003 due to the effects of tourism, infection of wildlife, and issues with

invasive species.

[56] In 2010, Yellowstone National Park was honored with its own

quarter under the America the Beautiful Quarters Program.

[57]

Justin Ferrell explores three moral sensibilities that motivated

activists in dealing with Yellowstone. First came the utilitarian vision

of maximum exploitation of natural resources, characteristic of

developers in the late 19th century. Second was the spiritual vision of

nature inspired by the Romanticism and the transcendentalists the

mid-19th century. The twentieth century saw the biocentric moral vision

that focuses on the health of the ecosystem as theorized by

Aldo Leopold, which led to the expansion of federally protected areas and to the surrounding ecosystems.

[58]

Heritage and Research Center

The Heritage and Research Center is located at

Gardiner, Montana, near the north entrance to the park.

[59]

The center is home to the Yellowstone National Park's museum

collection, archives, research library, historian, archeology lab, and

herbarium.

The Yellowstone National Park Archives maintain collections of

historical records of Yellowstone and the National Park Service. The

collection includes the administrative records of Yellowstone, as well

as resource management records, records from major projects, and donated

manuscripts and personal papers. The archives are affiliated with the

National Archives and Records Administration.

[60][61]

Geography

Approximately 96 percent of the land area of Yellowstone National Park is located within the state of Wyoming.

[7]

Another three percent is within Montana, with the remaining one percent

in Idaho. The park is 63 miles (101 km) north to south, and 54 miles

(87 km) west to east by air. Yellowstone is 2,219,789 acres (898,317 ha;

3,468.420 sq mi)

[1] in area, larger than the states of

Rhode Island or

Delaware.

Rivers and lakes cover five percent of the land area, with the largest

water body being Yellowstone Lake at 87,040 acres (35,220 ha;

136.00 sq mi). Yellowstone Lake is up to 400 feet (120 m) deep and has

110 miles (180 km) of shoreline. At an elevation of 7,733 feet (2,357 m)

above sea level, Yellowstone Lake is the largest high altitude lake in

North America. Forests comprise 80 percent of the land area of the park;

most of the rest is

grassland.

[7]

The

Continental Divide of North America runs diagonally through the southwestern part of the park. The divide is a

topographic

feature that separates Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean water

drainages. About one third of the park lies on the west side of the

divide. The origins of the Yellowstone and

Snake Rivers

are near each other but on opposite sides of the divide. As a result,

the waters of the Snake River flow to the Pacific Ocean, while those of

the Yellowstone find their way to the Atlantic Ocean via the

Gulf of Mexico.

Aerial view, 3D computer generated image

The park sits on the

Yellowstone Plateau, at an average elevation of 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above sea level. The plateau is bounded on nearly all sides by

mountain ranges of the

Middle Rocky Mountains, which range from 9,000 to 11,000 feet (2,700 to 3,400 m) in elevation. The highest point in the park is atop

Eagle Peak (11,358 feet or 3,462 metres) and the lowest is along Reese Creek (5,282 feet or 1,610 metres).

[7] Nearby mountain ranges include the

Gallatin Range to the northwest, the

Beartooth Mountains in the north, the

Absaroka Range to the east, and the

Teton Range and the

Madison Range to the southwest and west. The most prominent summit on the Yellowstone Plateau is

Mount Washburn at 10,243 feet (3,122 m).

Yellowstone National Park has one of the world's largest

petrified forests,

trees which were long ago buried by ash and soil and transformed from

wood to mineral materials. This ash and other volcanic debris are

believed to have come from the park area itself. This is largely because

Yellowstone is actually a massive caldera of a supervolcano. There are

290

waterfalls of at least 15 feet (4.6 m) in the park, the highest being the

Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River at 308 feet (94 m).

[7]

Three deep canyons are located in the park, cut through the volcanic

tuff of the Yellowstone Plateau by rivers over the last 640,000 years.

The

Lewis River flows through

Lewis Canyon in the south, and the

Yellowstone River has carved two colorful canyons, the

Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and the Black Canyon of the Yellowstone in its journey north.

Geology

History

Columnar basalt near Tower Falls; large floods of basalt and other lava

types preceded mega-eruptions of superheated ash and pumice

Yellowstone is at the northeastern end of the

Snake River Plain, a great U-shaped arc through the mountains that extends from

Boise, Idaho some 400 miles (640 km) to the west. This feature traces the route of the

North American Plate over the last 17 million years as it was transported by

plate tectonics across a stationary

mantle hotspot. The landscape of present-day Yellowstone National Park is the most recent manifestation of this

hotspot below the

crust of the Earth.

[62]

The

Yellowstone Caldera is the largest volcanic system in North America. It has been termed a "

supervolcano" because the caldera was formed by exceptionally large explosive eruptions. The

magma chamber

that lies under Yellowstone is estimated to be a single connected

chamber, about 37 miles (60 km) long, 18 miles (29 km) wide, and 3 to 7

miles (5 to 12 km) deep.

[63] The current

caldera

was created by a cataclysmic eruption that occurred 640,000 years ago,

which released more than 240 cubic miles (1,000 km³) of ash, rock and

pyroclastic materials.

[64] This eruption was more than 1,000 times larger than the

1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

[65] It produced a caldera nearly five eighths of a mile (1 km) deep and 45 by 28 miles (72 by 45 km) in area and deposited the

Lava Creek Tuff, a

welded tuff geologic formation.

The most violent known eruption, which occurred 2.1 million years ago,

ejected 588 cubic miles (2,450 km³) of volcanic material and created the

rock formation known as the

Huckleberry Ridge Tuff and created the

Island Park Caldera.

[66] A smaller eruption ejected 67 cubic miles (280 km³) of material 1.3 million years ago, forming the

Henry's Fork Caldera and depositing the

Mesa Falls Tuff.

[65]

Each of the three climactic eruptions released vast amounts of ash

that blanketed much of central North America, falling many hundreds of

miles away. The amount of ash and gases released into the atmosphere

probably caused significant impacts to world weather patterns and led to

the

extinction of some species, primarily in North America.

[67]

A subsequent caldera-forming eruption occurred about 160,000 years

ago. It formed the relatively small caldera that contains the

West Thumb

of Yellowstone Lake. Since the last supereruption, a series of smaller

eruptive cycles between 640,000 and 70,000 years ago, has nearly filled

in the Yellowstone Caldera with 80 different eruptions of

rhyolitic lavas such as those that can be seen at

Obsidian Cliffs and

basaltic lavas which can be viewed at

Sheepeater Cliff.

Lava strata are most easily seen at the Grand Canyon of the

Yellowstone, where the Yellowstone River continues to carve into the

ancient lava flows. The canyon is a classic

V-shaped valley, indicative of river-type erosion rather than erosion caused by

glaciation.

[66]

Each eruption is part of an eruptive cycle that climaxes with the

partial collapse of the roof of the volcano's partially emptied magma

chamber. This creates a collapsed depression, called a caldera, and

releases vast amounts of volcanic material, usually through fissures

that ring the caldera. The time between the last three cataclysmic

eruptions in the Yellowstone area has ranged from 600,000 to

800,000 years, but the small number of such climactic eruptions cannot

be used to make an accurate prediction for future volcanic events.

[68]

Geysers and the hydrothermal system

Old Faithful Geyser erupts approximately every 91 minutes.

The most famous

geyser in the park, and perhaps the world, is

Old Faithful Geyser, located in

Upper Geyser Basin.

Castle Geyser,

Lion Geyser and

Beehive Geyser are in the same basin. The park contains the largest active geyser in the world—

Steamboat Geyser in the

Norris Geyser Basin.

A study that was completed in 2011 found that at least 1283 geysers

have erupted in Yellowstone. Of these, an average of 465 are active in a

given year.

[69][70]

Yellowstone contains at least 10,000 geothermal features altogether.

Half the geothermal features and two-thirds of the world's geysers are

concentrated in Yellowstone.

[71]

In May 2001, the

U.S. Geological Survey, Yellowstone National Park, and the

University of Utah

created the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO), a partnership for

long-term monitoring of the geological processes of the Yellowstone

Plateau volcanic field, for disseminating information concerning the

potential hazards of this geologically active region.

[72]

Steamboat Geyser is the world's largest active geyser.

In 2003, changes at the Norris Geyser Basin resulted in the temporary closure of some trails in the basin. New

fumaroles

were observed, and several geysers showed enhanced activity and

increasing water temperatures. Several geysers became so hot that they

were transformed into purely steaming features; the water had become

superheated and they could no longer erupt normally.

[73]

This coincided with the release of reports of a multiple year United

States Geological Survey research project which mapped the bottom of

Yellowstone Lake and identified a structural dome that had uplifted at

some time in the past. Research indicated that these uplifts posed no

immediate threat of a volcanic eruption, since they may have developed

long ago, and there had been no temperature increase found near the

uplifts.

[74]

On March 10, 2004, a biologist discovered 5 dead bison which apparently

had inhaled toxic geothermal gases trapped in the Norris Geyser Basin

by a seasonal atmospheric inversion. This was closely followed by an

upsurge of earthquake activity in April 2004.

[75]

In 2006, it was reported that the Mallard Lake Dome and the Sour Creek

Dome— areas that have long been known to show significant changes in

their ground movement— had risen at a rate of 1.5 to 2.4 inches (3.8 to

6.1 cm) per year from mid–2004 through 2006. As of late 2007, the uplift

has continued at a reduced rate.

[76][77]

These events inspired a great deal of media attention and speculation

about the geologic future of the region. Experts responded to the

conjecture by informing the public that there was no increased risk of a

volcanic eruption in the near future.

[78] However, these changes demonstrate the dynamic nature of the Yellowstone hydrothermal system.

Earthquakes

Yellowstone experiences thousands of small earthquakes every year,

virtually all of which are undetectable to people. There have been six

earthquakes with at least

magnitude 6 or greater in historical times, including a the 7.5‑magnitude

Hebgen Lake earthquake which occurred just outside the northwest boundary of the park in 1959. This quake triggered a huge

landslide, which caused a partial dam collapse on

Hebgen Lake; immediately downstream, the

sediment from the landslide dammed the river and created a new lake, known as

Earthquake Lake.

Twenty-eight people were killed, and property damage was extensive in

the immediate region. The earthquake caused some geysers in the

northwestern section of the park to erupt, large cracks in the ground

formed and emitted steam, and some hot springs that normally have clear

water turned muddy.

[53] A 6.1‑magnitude earthquake struck inside the park on June 30, 1975, but damage was minimal.

Upper Terraces of Mammoth Hot Springs

For three months in 1985, 3,000 minor earthquakes were detected in

the northwestern section of the park, during what has been referred to

as an

earthquake swarm, and has been attributed to minor subsidence of the Yellowstone caldera.

[65]

Beginning on April 30, 2007, 16 small earthquakes with magnitudes up to

2.7 occurred in the Yellowstone Caldera for several days. These swarms

of earthquakes are common, and there have been 70 such swarms between

1983 and 2008.

[79]

In December 2008, over 250 earthquakes were measured over a four-day

span under Yellowstone Lake, the largest measuring a magnitude of 3.9.

[80] In January 2010, more than 250 earthquakes were detected over a two-day period.

[81]

Seismic activity in Yellowstone National Park continues and is reported

hourly by the Earthquake Hazards Program of the U.S. Geological Survey.

[82]

On March 30, 2014, a magnitude 4.8 earthquake struck almost the very

middle of Yellowstone near the Norris Basin at 6:34 am; reports

indicated no damage. This was the largest earthquake to hit the park

since February 22, 1980.

[83]

Biology and ecology

Meadow in Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is the centerpiece of the 20 million acre/31,250 square-mile (8,093,712 ha/80,937 km

2) Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a region that includes

Grand Teton National Park, adjacent

National Forests and expansive

wilderness

areas in those forests. The ecosystem is the largest remaining

continuous stretch of mostly undeveloped pristine land in the

continental United States, considered the world's largest intact

ecosystem in the northern temperate zone.

[12] With the successful

wolf reintroduction

program, which began in the 1990s, virtually all the original faunal

species known to inhabit the region when white explorers first entered

the area can still be found there.

Flora

Over 1,700

species of trees and other

vascular plants are native to the park. Another 170 species are considered to be

exotic species and are non-native. Of the eight

conifer tree species documented,

Lodgepole Pine forests cover 80% of the total forested areas.

[7] Other conifers, such as

Subalpine Fir,

Engelmann Spruce,

Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir and

Whitebark Pine, are found in scattered groves throughout the park. As of 2007, the whitebark pine is threatened by a fungus known as

white pine blister rust;

however, this is mostly confined to forests well to the north and west.

In Yellowstone, about seven percent of the whitebark pine species have

been impacted with the fungus, compared to nearly complete infestations

in northwestern Montana.

[84] Quaking Aspen and

willows are the most common species of

deciduous

trees. The aspen forests have declined significantly since the early

20th century, but scientists at Oregon State University attribute recent

recovery of the aspen to the reintroduction of wolves which has changed

the grazing habits of local elk.

[85]

Yellowstone sand verbena are endemic to Yellowstone's lakeshores.

There are dozens of species of flowering plants that have been

identified, most of which bloom between the months of May and September.

[86] The

Yellowstone Sand Verbena

is a rare flowering plant found only in Yellowstone. It is closely

related to species usually found in much warmer climates, making the

sand verbena an enigma. The estimated 8,000 examples of this rare

flowering plant all make their home in the sandy soils on the shores of

Yellowstone Lake, well above the waterline.

[87]

In Yellowstone's hot waters, bacteria form mats of bizarre shapes

consisting of trillions of individuals. These bacteria are some of the

most primitive life forms on earth. Flies and other

arthropods

live on the mats, even in the middle of the bitterly cold winters.

Initially, scientists thought that microbes there gained sustenance only

from

sulfur. In 2005 researchers from the

University of Colorado at Boulder discovered that the sustenance for at least some of the diverse

hyperthermophilic species is

molecular hydrogen.

[88]

Thermus aquaticus is a

bacterium

found in the Yellowstone hot springs that produces an important enzyme

(Taq polymerase) that is easily replicated in the lab and is useful in

replicating

DNA as part of the

polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) process. The retrieval of these bacteria can be achieved with no

impact to the ecosystem. Other bacteria in the Yellowstone hot springs

may also prove useful to scientists who are searching for cures for

various diseases.

[89] In 2016, researchers from Uppsala University reported the discovery of a class of thermophiles,

Hadesarchaea,

in Yellowstone's Culex Basin. These organisms are capable of converting

carbon monoxide and water to carbon dioxide and oxygen.

[90][91]

Non-native plants sometimes threaten native species by using up

nutrient resources. Though exotic species are most commonly found in

areas with the greatest human visitation, such as near roads and at

major tourist areas, they have also spread into the backcountry.

Generally, most exotic species are controlled by pulling the plants out

of the soil or by spraying, both of which are time consuming and

expensive.

[92]

Fauna

Yellowstone is widely considered to be the finest

megafauna wildlife habitat in the

lower 48 states. There are almost 60 species of

mammals in the park, including the

gray wolf,

coyote, the

threatened Canadian lynx, and

grizzly bears.

[7] Other large mammals include the

bison (often referred to as buffalo),

black bear,

elk,

moose,

mule deer,

white-tailed deer,

mountain goat,

pronghorn,

bighorn sheep, and

cougar.

Bison graze near a hot spring.

The

Yellowstone Park bison herd is the largest public herd of

American bison

in the United States. The relatively large bison populations are a

concern for ranchers, who fear that the species can transmit

bovine diseases to their domesticated cousins. In fact, about half of Yellowstone's bison have been exposed to

brucellosis, a bacterial disease that came to North America with European cattle that may cause cattle to

miscarry.

The disease has little effect on park bison, and no reported case of

transmission from wild bison to domestic livestock has been filed.

However, the

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has stated that bison are the "likely source" of the spread of the disease in cattle in Wyoming and

North Dakota. Elk also carry the disease and are believed to have transmitted the infection to horses and cattle.

[93]

Bison once numbered between 30 and 60 million individuals throughout

North America, and Yellowstone remains one of their last strongholds.

Their populations had increased from less than 50 in the park in 1902 to

4,000 by 2003. The Yellowstone Park bison herd reached a peak in 2005

with 4,900 animals. Despite a summer estimated population of 4,700 in

2007, the number dropped to 3,000 in 2008 after a harsh winter and

controversial brucellosis management sending hundreds to slaughter.

[94]

The Yellowstone Park bison herd is believed to be one of only four free

roaming and genetically pure herds on public lands in North America.

The other three herds are the

Henry Mountains bison herd of

Utah, at

Wind Cave National Park in

South Dakota and in

Elk Island National Park in

Alberta.

[95]

Elk mother nursing her calf.

To combat the perceived threat of

brucellosis

transmission to cattle, national park personnel regularly harass bison

herds back into the park when they venture outside of the area's

borders. During the winter of 1996–97, the bison herd was so large that

1,079 bison that had exited the park were shot or sent to slaughter.

[93] Animal rights

activists argue that this is a cruel practice and that the possibility

for disease transmission is not as great as some ranchers maintain.

Ecologists point out that the bison are merely traveling to seasonal

grazing areas that lie within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that

have been converted to cattle grazing, some of which are within National

Forests and are leased to private ranchers. APHIS has stated that with

vaccinations and other means, brucellosis can be eliminated from the

bison and elk herds throughout Yellowstone.

[93]

A reintroduced wolf in Yellowstone National Park

Starting in 1914, in an effort to protect elk populations, the U.S.

Congress appropriated funds to be used for the purposes of "destroying

wolves,

prairie dogs,

and other animals injurious to agriculture and animal husbandry" on

public lands. Park Service hunters carried out these orders, and by 1926

they had killed 136 wolves, and wolves were virtually eliminated from

Yellowstone.

[96] Further exterminations continued until the National Park Service ended the practice in 1935. With the passing of the

Endangered Species Act in 1973, the wolf was one of the first mammal species listed.

[96] After the wolves were extirpated from Yellowstone, the

coyote

then became the park's top canine predator. However, the coyote is not

able to bring down large animals, and the result of this lack of a top

predator on these populations was a marked increase in lame and sick

megafauna.

Bison in Yellowstone National Park

By the 1990s, the Federal government had reversed its views on wolves. In a controversial decision by the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

(which oversees threatened and endangered species), northwestern wolves

imported from Canada were reintroduced into the park. Reintroduction

efforts have been successful with populations remaining relatively

stable. A survey conducted in 2005 reported that there were 13 wolf

packs, totaling 118 individuals in Yellowstone and 326 in the entire

ecosystem. These park figures were lower than those reported in 2004 but

may be attributable to wolf migration to other nearby areas as

suggested by the substantial increase in the Montana population during

that interval.

[97] Almost all the wolves documented were descended from the 66 wolves reintroduced in 1995–96.

[97]

The recovery of populations throughout the states of Wyoming, Montana

and Idaho has been so successful that on February 27, 2008, the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service removed the Northern Rocky Mountain wolf

population from the endangered species list.

[98]

Black bear and cubs in the Tower-Roosevelt area

An estimated 600 grizzly bears live in the Greater Yellowstone

Ecosystem, with more than half of the population living within

Yellowstone. The grizzly is currently listed as a threatened species,

however the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has announced that they

intend to take it off the endangered species list for the Yellowstone

region but will likely keep it listed in areas where it has not yet

recovered fully. Opponents of delisting the grizzly are concerned that

states might once again allow hunting and that better conservation

measures need to be implemented to ensure a sustainable population.

[99] Black bears

are common in the park and were a park symbol due to visitor

interaction with the bears starting in 1910. Feeding and close contact

with bears has not been permitted since the 1960s to reduce their desire

for human foods.

[100] Yellowstone is one of the few places in the United States where black bears can be seen coexisting with grizzly bears.

[100]

Black bear observations occur most often in the park's northern ranges

and in the Bechler area which is in the park's southwestern corner.

[101]

Population figures for elk are in excess of 30,000—the largest

population of any large mammal species in Yellowstone. The northern herd

has decreased enormously since the mid‑1990s; this has been attributed

to wolf predation and causal effects such as elk using more forested

regions to evade predation, consequently making it harder for

researchers to accurately count them.

[102]

The northern herd migrates west into southwestern Montana in the

winter. The southern herd migrates southward, and the majority of these

elk winter on the

National Elk Refuge,

immediately southeast of Grand Teton National Park. The southern herd

migration is the largest mammalian migration remaining in the U.S.

outside of Alaska.

Pronghorn are commonly found on the grasslands in the park.

In 2003 the tracks of one female lynx and her cub were spotted and

followed for over 2 miles (3.2 km). Fecal material and other evidence

obtained were tested and confirmed to be those of a lynx. No visual

confirmation was made, however. Lynx have not been seen in Yellowstone

since 1998, though

DNA taken from hair samples obtained in 2001 confirmed that lynx were at least transient to the park.

[103] Other less commonly seen mammals include the mountain lion and

wolverine. The mountain lion has an estimated population of only 25 individuals parkwide.

[104] The wolverine is another rare park mammal, and accurate population figures for this species are not known.

[105]

These uncommon and rare mammals provide insight into the health of

protected lands such as Yellowstone and help managers make

determinations as to how best to preserve habitats.

Eighteen species of fish live in Yellowstone, including the core range of the

Yellowstone cutthroat trout—a fish highly sought by

anglers.

[7][106]

The Yellowstone cutthroat trout has faced several threats since the

1980s, including the suspected illegal introduction into Yellowstone

Lake of

lake trout, an

invasive species which consume the smaller cutthroat trout.

[107] Although lake trout were established in

Shoshone and

Lewis

lakes in the Snake River drainage from U.S. Government stocking

operations in 1890, it was never officially introduced into the

Yellowstone River drainage.

[108] The cutthroat trout has also faced an ongoing drought, as well as the accidental introduction of a parasite—

whirling disease—which

causes a terminal nervous system disease in younger fish. Since 2001,

all native sport fish species caught in Yellowstone waterways are

subject to a catch and release law.

[106] Yellowstone is also home to six species of

reptiles, such as the

painted turtle and

Prairie rattlesnake, and four species of

amphibians, including the

Boreal Chorus Frog.

[109]

311 species of birds have been reported, almost half of which nest in Yellowstone.

[7] As of 1999, twenty-six pairs of nesting bald eagles have been documented. Extremely rare sightings of

whooping cranes

have been recorded, however only three examples of this species are

known to live in the Rocky Mountains, out of 385 known worldwide.

[110] Other birds, considered to be species of special concern because of their rarity in Yellowstone, include the

common loon,

harlequin duck,

osprey,

peregrine falcon and the

trumpeter swan.

[111]

Forest fires

Fire in Yellowstone National Park

As

wildfire is a natural part of most ecosystems, plants that are

indigenous to Yellowstone have adapted in a variety of ways.

Douglas-fir have a thick bark which protects the inner section of the tree from most fires.

Lodgepole Pines

—the most common tree species in the park— generally have cones that

are only opened by the heat of fire. Their seeds are held in place by a

tough resin, and fire assists in melting the resin, allowing the seeds

to disperse. Fire clears out dead and downed wood, providing fewer

obstacles for lodgepole pines to flourish.

Subalpine Fir,

Engelmann Spruce,

Whitebark Pine, and other species tend to grow in colder and moister areas, where fire is less likely to occur.

Aspen

trees sprout new growth from their roots, and even if a severe fire

kills the tree above ground, the roots often survive unharmed because

they are insulated from the heat by soil.

[112]

The National Park Service estimates that in natural conditions,

grasslands in Yellowstone burned an average of every 20 to 25 years,

while forests in the park would experience fire about every 300 years.

[112]

About thirty-five natural forest fires are ignited each year by

lightning, while another six to ten are started by people— in most cases by accident. Yellowstone National Park has three

fire lookout towers,

each staffed by trained fire fighters. The easiest one to reach is atop

Mount Washburn, which has interpretive exhibits and an observation deck

open to the public.

[113] The park also monitors fire from the air and relies on visitor reports of smoke and/or flames.

[114]

Fire towers are staffed almost continuously from late June to

mid-September— the primary fire season. Fires burn with the greatest

intensity in the late afternoon and evening. Few fires burn more than

100 acres (40 ha), and the vast majority of fires reach only a little

over an acre (0.5 ha) before they burn themselves out.

[115]

Fire management focuses on monitoring dead and down wood quantities,

soil and tree moisture, and the weather, to determine those areas most

vulnerable to fire should one ignite. Current policy is to suppress all

human caused fires and to evaluate natural fires, examining the benefit

or detriment they may pose on the ecosystem. If a fire is considered to

be an immediate threat to people and structures, or will burn out of

control, then fire suppression is performed.

[116]

Wildfire in Yellowstone National Park produces a pyrocumulus cloud.

In an effort to minimize the chances of out of control fires and

threats to people and structures, park employees do more than just

monitor the potential for fire.

Controlled burns

are prescribed fires which are deliberately started to remove dead

timber under conditions which allow fire fighters an opportunity to

carefully control where and how much wood is consumed. Natural fires are

sometimes considered prescribed fires if they are left to burn. In

Yellowstone, unlike some other parks, there have been very few fires

deliberately started by employees as prescribed burns. However, over the

last 30 years, over 300 natural fires have been allowed to burn

naturally. In addition, fire fighters remove dead and down wood and

other hazards from areas where they will be a potential fire threat to

lives and property, reducing the chances of fire danger in these areas.

[117]

Fire monitors also regulate fire through educational services to the

public and have been known to temporarily ban campfires from campgrounds

during periods of high fire danger. The common notion in early United

States land management policies was that all forest fires were bad. Fire

was seen as a purely destructive force and there was little

understanding that it was an integral part of the ecosystem.

Consequently, until the 1970s, when a better understanding of wildfire

was developed, all fires were suppressed. This led to an increase in

dead and dying forests, which would later provide the fuel load for

fires that would be much harder, and in some cases, impossible to

control. Fire Management Plans were implemented, detailing that natural

fires should be allowed to burn if they posed no immediate threat to

lives and property.

A crown fire approaches the Old Faithful complex on September 7, 1988.

1988 started with a wet spring season although by summer, drought

began moving in throughout the northern Rockies, creating the driest

year on record to that point. Grasses and plants which grew well in the

early summer from the abundant spring moisture produced plenty of grass,

which soon turned to dry tinder. The National Park Service began

firefighting efforts to keep the fires under control, but the extreme

drought made suppression difficult. Between July 15 and 21, 1988, fires

quickly spread from 8,500 acres (3,400 ha; 13.3 sq mi) throughout the

entire Yellowstone region, which included areas outside the park, to

99,000 acres (40,000 ha; 155 sq mi) on the park land alone. By the end

of the month, the fires were out of control. Large fires burned

together, and on August 20, 1988, the single worst day of the fires,

more than 150,000 acres (61,000 ha; 230 sq mi) were consumed. Seven

large fires were responsible for 95% of the 793,000 acres (321,000 ha;

1,239 sq mi) that were burned over the next couple of months. A total of

25,000 firefighters and U.S. military forces participated in the

suppression efforts, at a cost of 120 million dollars. By the time

winter brought snow that helped extinguish the last flames, the fires

had destroyed 67 structures and caused several million dollars in

damage.

[55] Though no civilian lives were lost, two personnel associated with the firefighting efforts were killed.

Contrary to media reports and speculation at the time, the fires

killed very few park animals— surveys indicated that only about 345 elk

(of an estimated 40,000–50,000), 36 deer, 12 moose, 6 black bears, and 9

bison had perished. Changes in fire management policies were

implemented by land management agencies throughout the United States,

based on knowledge gained from the 1988 fires and the evaluation of

scientists and experts from various fields. By 1992, Yellowstone had

adopted a new fire management plan which observed stricter guidelines

for the management of natural fires.

[55]

Climate

Winter scene in Yellowstone

Yellowstone climate is greatly influenced by altitude, with lower

elevations generally found to be warmer year-round. The record high

temperature was 99 °F (37 °C) in 2002, while the coldest temperature

recorded is −66 °F (−54 °C) in 1933.

[7]

During the summer months of June through early September, daytime highs

are normally in the 70 to 80 °F (21 to 27 °C) range, while night time

lows can go to below freezing (0 °C) especially at higher altitudes.

Summer afternoons are frequently accompanied by

thunderstorms.

Spring and fall temperatures range between 30 and 60 °F (−1 and 16 °C)

with nights in the teens to single digits (−5 to −20 °C). Winter in

Yellowstone is accompanied by high temperatures usually between zero and

20 °F (−20 to −5 °C) and nighttime temperatures below 0 °F (−18 °C)

for most of the winter.

[118]

Precipitation in Yellowstone is highly variable and ranges from 15

inches (380 mm) annually near Mammoth Hot Springs, to 80 inches

(2,000 mm) in the southwestern sections of the park. The precipitation

of Yellowstone is greatly influenced by the moisture channel formed by

the

Snake River Plain

to the west that was, in turn, formed by Yellowstone itself. Snow is

possible in any month of the year, but most common between November and

April, with averages of 150 inches (3,800 mm) annually around

Yellowstone Lake, to twice that amount at higher elevations.

[118]

Tornadoes in Yellowstone are rare; however, on July 21, 1987, the most powerful tornado recorded in Wyoming touched down in the

Teton Wilderness of

Bridger-Teton National Forest and hit Yellowstone National Park. Called the

Teton–Yellowstone tornado, it was classified as an

F4,

with wind speeds estimated at between 207 and 260 miles per hour (333

and 418 km/h). The tornado left a path of destruction 1 to 2 miles (1.6

to 3.2 km) wide, and 24 miles (39 km) long, and leveled 15,000 acres

(6,100 ha; 23 sq mi) of mature pine forest.

[119]

The climate at Yellowstone Lake is classified as

subarctic (Dfc), according to

Köppen-Geiger climate classification, while at the park headquarters the classification is

humid continental (Dfb).

Recreation

Union Pacific Railroad Brochure Promoting Travel to Park (1921)

Yellowstone ranks among the most popular national parks in the United

States. Since the mid-1960s, at least 2 million tourists have visited

the park almost every year.

[124]

Average annual visitation increased to 3.5 million during the ten-year

period from 2007 to 2016, with a record of 4,257,177 recreational

visitors in 2016.

[2] July is the busiest month for Yellowstone National Park.

[125]

At peak summer levels, 3,700 employees work for Yellowstone National

Park concessionaires. Concessionaires manage nine hotels and lodges,

with a total of 2,238 hotel rooms and cabins available. They also

oversee gas stations, stores and most of the campgrounds. Another 800

employees work either permanently or seasonally for the National Park

Service.

[7]

Park service roads lead to major features; however, road

reconstruction has produced temporary road closures. Yellowstone is in

the midst of a long term road reconstruction effort, which is hampered

by a short repair season. In the winter, all roads aside from the one

which enters from

Gardiner, Montana, and extends to

Cooke City, Montana, are closed to wheeled vehicles.

[126] Park roads are closed to wheeled vehicles from early November to mid April, but some park roads remain closed until mid-May.

[127] The park has 310 miles (500 km) of paved roads which can be accessed from five different entrances.

[7]

There is no public transportation available inside the park, but

several tour companies can be contacted for guided motorized transport.

In the winter, concessionaires operate guided

snowmobile and

snow coach tours, though their numbers and access are based on quotas established by the National Park Service.

[128]

Facilities in the Old Faithful, Canyon and Mammoth Hot Springs areas of

the park are very busy during the summer months. Traffic jams created

by road construction or by people observing wildlife can result in long

delays.

The National Park Service maintains 9 visitor centers and museums and

is responsible for maintenance of historical structures and many of the

other 2,000 buildings. These structures include National Historical

Landmarks such as the

Old Faithful Inn built from 1903 to 1904 and the entire

Fort Yellowstone – Mammoth Hot Springs Historic District.

An historical and educational tour is available at Fort Yellowstone

which details the history of the National Park Service and the

development of the park. Campfire programs, guided walks and other

interpretive presentations are available at numerous locations in the

summer, and on a limited basis during other seasons.

Camping is available at a dozen campgrounds with more than 2,000 campsites.

[7] Camping is also available in surrounding National Forests, as well as in Grand Teton National Park to the south.

Backcountry campsites are accessible only by foot or by

horseback and require a permit. There are 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of hiking trails available.

[129] The park is not considered to be a good destination for

mountaineering

because of the instability of volcanic rock which predominates.

Visitors with pets are required to keep them on a leash at all times and

are limited to areas near roadways and in "frontcountry" zones such as

drive in campgrounds.

[130]

Around thermal features, wooden and paved trails have been constructed

to ensure visitor safety, and most of these areas are handicapped

accessible. The National Park Service maintains a year-round clinic at

Mammoth Hot Springs and provides emergency services throughout the year.

[131]

Hunting is not permitted, though it is allowed in the surrounding

national forests during open season. Fishing is a popular activity, and a

Yellowstone Park fishing license is required to fish in park waters.

[132] Many park waters are

fly fishing only and all native fish species are

catch and release only.

[133] Boating is prohibited on rivers and creeks except for a 5 miles (8.0 km) stretch of the Lewis River between Lewis and

Shoshone Lake, and it is open to non-motorized use only. Yellowstone Lake has a marina, and the lake is the most popular boating destination.

[134]

Vintage photo of human-habituated bears seeking food from visitors.

In the early history of the park, visitors were allowed, and

sometimes even encouraged, to feed the bears. Visitors welcomed the

chance to get their pictures taken with the bears, who had learned to

beg for food. This led to numerous injuries to humans each year. In

1970, park officials changed their policy and started a vigorous program

to educate the public on the dangers of close contact with bears, and

to try to eliminate opportunities for bears to find food in campgrounds

and trash collection areas. Although it has become more difficult to

observe bears in recent years, the number of human injuries and deaths

has taken a significant drop and visitors are in less danger.

[135] The eighth recorded bear-related death in the park's history occurred in August 2015.

[136]

Other protected lands in the region include

Caribou-Targhee,

Gallatin,

Custer,

Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests. The National Park Service's

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway is to the south and leads to Grand Teton National Park. The famed

Beartooth Highway provides access from the northeast and has spectacular high altitude scenery. Nearby communities include

West Yellowstone, Montana;

Cody, Wyoming;

Red Lodge, Montana;

Ashton, Idaho; and

Gardiner, Montana. The closest air transport is available by way of

Bozeman, Montana;

Billings, Montana;

Jackson;

Cody, Wyoming, or

Idaho Falls, Idaho.

[137] Salt Lake City, 320 miles (510 km) to the south, is the closest large metropolitan area.

Legal jurisdiction

Street map of Yellowstone National Park at the northwest corner of Wyoming

The entire park is within the jurisdiction of the

United States District Court for the District of Wyoming,

making it the only federal court district that includes portions of

more than one state (Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming). Law professor Brian

C. Kalt has argued that it may be impossible to impanel a jury in

compliance with the

Vicinage Clause of the

Sixth Amendment

for a crime committed solely in the unpopulated Idaho portion of the

park (and that it would be difficult to do so for a crime committed

solely in the lightly populated Montana portion).

[138]

One defendant, who was accused of a wildlife-related crime in the

Montana portion of the park, attempted to raise this argument but

eventually pleaded guilty.

[139][140]

is the thermal energy in joules

is the heat transfer coefficient (assumed independent of T here) (W/(m2 K))

is the heat transfer surface area (m2)

is the temperature of the object's surface and interior (since these are the same in this approximation)

is the temperature of the environment; i.e. the temperature suitably far from the surface

is the time-dependent thermal gradient between environment and object

(total thermal energy content) which is proportional to

(total thermal energy content) which is proportional to  (simple total heat capacity) and

(simple total heat capacity) and  (the temperature of the body), then

(the temperature of the body), then  . It is expected that the system will experience exponential decay in the temperature difference of body and surroundings as a function of time. This is proven in the following sections:

. It is expected that the system will experience exponential decay in the temperature difference of body and surroundings as a function of time. This is proven in the following sections: comes the relation

comes the relation  .

Differentiating this equation with regard to time gives the identity

(valid so long as temperatures in the object are uniform at any given

time):

.

Differentiating this equation with regard to time gives the identity

(valid so long as temperatures in the object are uniform at any given

time):  . This expression may be used to replace

. This expression may be used to replace  in the first equation which begins this section, above. Then, if

in the first equation which begins this section, above. Then, if  is the temperature of such a body at time

is the temperature of such a body at time  , and

, and  is the temperature of the environment around the body:

is the temperature of the environment around the body: is a positive constant characteristic of the system, which must be in units of

is a positive constant characteristic of the system, which must be in units of  , and is therefore sometimes expressed in terms of a characteristic time constant

, and is therefore sometimes expressed in terms of a characteristic time constant  given by:

given by:  . Thus, in thermal systems,

. Thus, in thermal systems,  . (The total heat capacity

. (The total heat capacity  of a system may be further represented by its mass-specific heat capacity

of a system may be further represented by its mass-specific heat capacity  multiplied by its mass

multiplied by its mass  , so that the time constant

, so that the time constant  is also given by

is also given by  ).

).is defined as :

where

is the initial temperature difference at time 0,

, as a single function of time to be found, or "solved for."

, as a single function of time to be found, or "solved for."