Propaganda is information that is not objective and is used primarily to influence an audience and further an agenda, often by presenting facts selectively to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is presented. Propaganda is often associated with material prepared by governments, but activist groups, companies and the media can also produce propaganda.

In the twentieth century, the term propaganda has often been associated with a manipulative approach, but propaganda historically was a neutral descriptive term.

A wide range of materials and media are used for conveying propaganda messages, which changed as new technologies were invented, including paintings, cartoons, posters, pamphlets, films, radio shows, TV shows, and websites. Propaganda is now moving into a digital age utillizing bots, algorithms, to create computational propaganda and spread online fake or biased news using social media.

In a 1929 literary debate with Edward Bernays, Everett Dean Martin argues that, “Propaganda is making puppets of us. We are moved by hidden strings which the propagandist manipulates.”

Etymology

From the 1790s, the term began being used also to refer to propaganda in secular activities. The term began taking a pejorative or negative connotation in the mid-19th century, when it was used in the political sphere.

History

Primitive forms of propaganda have been a human activity as far back as reliable recorded evidence exists. The Behistun Inscription (c. 515 BC) detailing the rise of Darius I to the Persian throne is viewed by most historians as an early example of propaganda. Another striking example of propaganda during Ancient History is the last Roman civil wars (44-30 BC) during which Octavian and Mark Antony blame each other for obscure and degrading origins, cruelty, cowardice, oratorical and literary incompetence, debaucheries, luxury, drunkenness and other slanders. This defamation took the form of uituperatio (Roman rhetorical genre of the invective) which was decisive for shaping the Roman public opinion at this time.Propaganda during the Reformation, helped by the spread of the printing press throughout Europe, and in particular within Germany, caused new ideas, thoughts, and doctrine to be made available to the public in ways that had never been seen before the 16th century. During the era of the American Revolution, the American colonies had a flourishing network of newspapers and printers who specialized in the topic on behalf of the Patriots (and to a lesser extent on behalf of the Loyalists).

A propaganda newspaper clipping that refers to the Bataan Death March in 1942

The first large-scale and organised propagation of government propaganda was occasioned by the outbreak of war in 1914. After the defeat of Germany in the First World War, military officials such as Erich Ludendorff suggested that British propaganda had been instrumental in their defeat. Adolf Hitler came to echo this view, believing that it had been a primary cause of the collapse of morale and the revolts in the German home front and Navy in 1918 (see also: Dolchstoßlegende). In Mein Kampf (1925) Hitler expounded his theory of propaganda, which provided a powerful base for his rise to power in 1933. Historian Robert Ensor explains that "Hitler...puts no limit on what can be done by propaganda; people will believe anything, provided they are told it often enough and emphatically enough, and that contradicters are either silenced or smothered in calumny." Most propaganda in Nazi Germany was produced by the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels. World War II saw continued use of propaganda as a weapon of war, building on the experience of WWI, by Goebbels and the British Political Warfare Executive, as well as the United States Office of War Information.

Anti-religious Soviet propaganda poster, the Russian text reads "Ban Religious Holidays!"

In the early 20th century, the invention of motion pictures gave propaganda-creators a powerful tool for advancing political and military interests when it came to reaching a broad segment of the population and creating consent or encouraging rejection of the real or imagined enemy. In the years following the October Revolution of 1917, the Soviet government sponsored the Russian film industry with the purpose of making propaganda films (e.g. the 1925 film The Battleship Potemkin glorifies Communist ideals.) In WWII, Nazi filmmakers produced highly emotional films to create popular support for occupying the Sudetenland and attacking Poland. The 1930s and 1940s, which saw the rise of totalitarian states and the Second World War, are arguably the "Golden Age of Propaganda". Leni Riefenstahl, a filmmaker working in Nazi Germany, created one of the best-known propaganda movies, Triumph of the Will. In the US, animation became popular, especially for winning over youthful audiences and aiding the U.S. war effort, e.g.,Der Fuehrer's Face (1942), which ridicules Hitler and advocates the value of freedom. US war films in the early 1940s were designed to create a patriotic mindset and convince viewers that sacrifices needed to be made to defeat the Axis Powers. Polish filmmakers in Great Britain created anti-nazi color film Calling mr. Smith (1943) about current nazi crimes in occupied Europe and about lies of nazi propaganda.

The West and the Soviet Union both used propaganda extensively during the Cold War. Both sides used film, television, and radio programming to influence their own citizens, each other, and Third World nations. George Orwell's novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four are virtual textbooks on the use of propaganda. During the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro stressed the importance of propaganda. Propaganda was used extensively by Communist forces in the Vietnam War as means of controlling people's opinions.

During the Yugoslav wars, propaganda was used as a military strategy by governments of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Croatia. Propaganda was used to create fear and hatred, and particularly incite the Serb population against the other ethnicities (Bosniaks, Croats, Albanians and other non-Serbs). Serb media made a great effort in justifying, revising or denying mass war crimes committed by Serb forces during these wars.

Public perceptions

In the early 20th century the term propaganda was used by the founders of the nascent public relations industry to refer to their people. This image died out around the time of World War II, as the industry started to avoid the word, given the pejorative connotation it had acquired. Literally translated from the Latin gerundive as "things that must be disseminated", in some cultures the term is neutral or even positive, while in others the term has acquired a strong negative connotation. The connotations of the term "propaganda" can also vary over time. For example, in Portuguese and some Spanish language speaking countries, particularly in the Southern Cone, the word "propaganda" usually refers to the most common manipulative media — "advertising".

Poster of the 19th-century Scandinavist movement

In English, propaganda was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of any given cause. During the 20th century, however, the term acquired a thoroughly negative meaning in western countries, representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly "compelling" claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies. According to Harold Lasswell, the term began to fall out of favor due to growing public suspicion of propaganda in the wake of its use during World War I by the Creel Committee in the United States and the Ministry of Information in Britain: Writing in 1928, Lasswell observed, "In democratic countries the official propaganda bureau was looked upon with genuine alarm, for fear that it might be suborned to party and personal ends. The outcry in the United States against Mr. Creel's famous Bureau of Public Information (or 'Inflammation') helped to din into the public mind the fact that propaganda existed. … The public's discovery of propaganda has led to a great of lamentation over it. Propaganda has become an epithet of contempt and hate, and the propagandists have sought protective coloration in such names as 'public relations council,' 'specialist in public education,' 'public relations adviser.' "

The term is essentially contested and some have argued for a neutral definition arguing that ethics depend on intent and context, others define it as necessarily unethical and negative. Dr Emma Briant defines it as "the deliberate manipulation of representations (including text, pictures, video, speech etc.) with the intention of producing any effect in the audience (e.g. action or inaction; reinforcement or transformation of feelings, ideas, attitudes or behaviours) that is desired by the propagandist.

Types

Identifying propaganda has always been a problem. The main difficulties have involved differentiating propaganda from other types of persuasion, and avoiding a biased approach. Richard Alan Nelson provides a definition of the term: "Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ideological, political or commercial purposes through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels." The definition focuses on the communicative process involved — or more precisely, on the purpose of the process, and allow "propaganda" to be considered objectively and then interpreted as positive or negative behavior depending on the perspective of the viewer or listener.

Propaganda poster in North Korean primary school

According to historian Zbyněk Zeman, propaganda is defined as either white, grey or black. White propaganda openly discloses its source and intent. Grey propaganda has an ambiguous or non-disclosed source or intent. Black propaganda purports to be published by the enemy or some organization besides its actual origins (compare with black operation, a type of clandestine operation in which the identity of the sponsoring government is hidden). In scale, these different types of propaganda can also be defined by the potential of true and correct information to compete with the propaganda. For example, opposition to white propaganda is often readily found and may slightly discredit the propaganda source. Opposition to grey propaganda, when revealed (often by an inside source), may create some level of public outcry. Opposition to black propaganda is often unavailable and may be dangerous to reveal, because public cognizance of black propaganda tactics and sources would undermine or backfire the very campaign the black propagandist supported.

Propaganda poster in North Korea

The propagandist seeks to change the way people understand an issue or situation for the purpose of changing their actions and expectations in ways that are desirable to the interest group. Propaganda, in this sense, serves as a corollary to censorship in which the same purpose is achieved, not by filling people's minds with approved information, but by preventing people from being confronted with opposing points of view. What sets propaganda apart from other forms of advocacy is the willingness of the propagandist to change people's understanding through deception and confusion rather than persuasion and understanding. The leaders of an organization know the information to be one sided or untrue, but this may not be true for the rank and file members who help to disseminate the propaganda.

Religious

Propaganda was often used to influence opinions and beliefs on religious issues, particularly during the split between the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant churches.More in line with the religious roots of the term, propaganda is also used widely in the debates about new religious movements (NRMs), both by people who defend them and by people who oppose them. The latter pejoratively call these NRMs cults. Anti-cult activists and Christian countercult activists accuse the leaders of what they consider cults of using propaganda extensively to recruit followers and keep them. Some social scientists, such as the late Jeffrey Hadden, and CESNUR affiliated scholars accuse ex-members of "cults" and the anti-cult movement of making these unusual religious movements look bad without sufficient reasons.

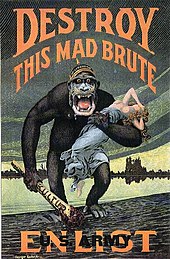

Wartime

A US Office for War Information poster uses stereotyped imagery to encourage Americans to work hard to contribute to the war effort

In post–World War II usage of the word "propaganda" more typically refers to political or nationalist uses of these techniques or to the promotion of a set of ideas.

Propaganda is a powerful weapon in war; it is used to dehumanize and create hatred toward a supposed enemy, either internal or external, by creating a false image in the mind of soldiers and citizens. This can be done by using derogatory or racist terms (e.g., the racist terms "Jap" and "gook" used during World War II and the Vietnam War, respectively), avoiding some words or language or by making allegations of enemy atrocities. Most propaganda efforts in wartime require the home population to feel the enemy has inflicted an injustice, which may be fictitious or may be based on facts (e.g., the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania by the German Navy in World War I). The home population must also believe that the cause of their nation in the war is just. In NATO doctrine, propaganda is defined as "Any information, ideas, doctrines, or special appeals disseminated to influence the opinion, emotions, attitudes, or behaviour of any specified group in order to benefit the sponsor either directly or indirectly." Within this perspective, information provided does not need to be necessarily false, but must be instead relevant to specific goals of the "actor" or "system" that performs it.

Propaganda is also one of the methods used in psychological warfare, which may also involve false flag operations in which the identity of the operatives is depicted as those of an enemy nation (e.g., The Bay of Pigs invasion used CIA planes painted in Cuban Air Force markings). The term propaganda may also refer to false information meant to reinforce the mindsets of people who already believe as the propagandist wishes (e.g., During the First World War, the main purpose of British propaganda was to encourage men join the army, and women to work in the country’s industry. The propaganda posters were used, because radios and TVs were not very common at that time.). The assumption is that, if people believe something false, they will constantly be assailed by doubts. Since these doubts are unpleasant, people will be eager to have them extinguished, and are therefore receptive to the reassurances of those in power. For this reason propaganda is often addressed to people who are already sympathetic to the agenda or views being presented. This process of reinforcement uses an individual's predisposition to self-select "agreeable" information sources as a mechanism for maintaining control over populations.

Propaganda may be administered in insidious ways. For instance, disparaging disinformation about the history of certain groups or foreign countries may be encouraged or tolerated in the educational system. Since few people actually double-check what they learn at school, such disinformation will be repeated by journalists as well as parents, thus reinforcing the idea that the disinformation item is really a "well-known fact", even though no one repeating the myth is able to point to an authoritative source. The disinformation is then recycled in the media and in the educational system, without the need for direct governmental intervention on the media. Such permeating propaganda may be used for political goals: by giving citizens a false impression of the quality or policies of their country, they may be incited to reject certain proposals or certain remarks or ignore the experience of others.

In the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the propaganda designed to encourage civilians was controlled by Stalin, who insisted on a heavy-handed style that educated audiences easily saw was inauthentic. On the other hand, the unofficial rumours about German atrocities were well founded and convincing. Stalin was a Georgian who spoke Russian with a heavy accent. That would not do for a national hero so starting in the 1930s all new visual portraits of Stalin were retouched to erase his Georgian facial characteristics and make him a more generalized Soviet hero. Only his eyes and famous mustache remained unaltered. Zhores Medvedev and Roy Medvedev say his "majestic new image was devised appropriately to depict the leader of all times and of all peoples."

Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits any propaganda for war as well as any advocacy of national or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence by law.

Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. The people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

Advertising

Propaganda shares techniques with advertising and public relations, each of which can be thought of as propaganda that promotes a commercial product or shapes the perception of an organization, person, or brand.

World War I propaganda poster for enlistment in the U.S. Army

Journalistic theory generally holds that news items should be objective, giving the reader an accurate background and analysis of the subject at hand. On the other hand, advertisements evolved from the traditional commercial advertisements to include also a new type in the form of paid articles or broadcasts disguised as news. These generally present an issue in a very subjective and often misleading light, primarily meant to persuade rather than inform. Normally they use only subtle propaganda techniques and not the more obvious ones used in traditional commercial advertisements. If the reader believes that a paid advertisement is in fact a news item, the message the advertiser is trying to communicate will be more easily "believed" or "internalized". Such advertisements are considered obvious examples of "covert" propaganda because they take on the appearance of objective information rather than the appearance of propaganda, which is misleading. Federal law specifically mandates that any advertisement appearing in the format of a news item must state that the item is in fact a paid advertisement.

Politics

Propaganda has become more common in political contexts, in particular to refer to certain efforts sponsored by governments, political groups, but also often covert interests. In the early 20th century, propaganda was exemplified in the form of party slogans. Propaganda also has much in common with public information campaigns by governments, which are intended to encourage or discourage certain forms of behavior (such as wearing seat belts, not smoking, not littering and so forth). Again, the emphasis is more political in propaganda. Propaganda can take the form of leaflets, posters, TV and radio broadcasts and can also extend to any other medium. In the case of the United States, there is also an important legal (imposed by law) distinction between advertising (a type of overt propaganda) and what the Government Accountability Office (GAO), an arm of the United States Congress, refers to as "covert propaganda".Roderick Hindery argues that propaganda exists on the political left, and right, and in mainstream centrist parties. Hindery further argues that debates about most social issues can be productively revisited in the context of asking "what is or is not propaganda?" Not to be overlooked is the link between propaganda, indoctrination, and terrorism/counterterrorism. He argues that threats to destroy are often as socially disruptive as physical devastation itself.

Anti-communist

propaganda in a 1947 comic book published by the Catechetical Guild

Educational Society warning of "the dangers of a Communist takeover"

Since 9/11 and the appearance of greater media fluidity, propaganda institutions, practices and legal frameworks have been evolving in the US and Britain. Dr Emma Louise Briant shows how this included expansion and integration of the apparatus cross-government and details attempts to coordinate the forms of propaganda for foreign and domestic audiences, with new efforts in strategic communication. These were subject to contestation within the US Government, resisted by Pentagon Public Affairs and critiqued by some scholars. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (section 1078 (a)) amended the US Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (popularly referred to as the Smith-Mundt Act) and the Foreign Relations Authorization Act of 1987, allowing for materials produced by the State Department and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) to be released within U.S. borders for the Archivist of the United States. The Smith-Mundt Act, as amended, provided that “the Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors shall make available to the Archivist of the United States, for domestic distribution, motion pictures, films, videotapes, and other material 12 years after the initial dissemination of the material abroad (...) Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors from engaging in any medium or form of communication, either directly or indirectly, because a United States domestic audience is or may be thereby exposed to program material, or based on a presumption of such exposure.” Public concerns were raised upon passage due to the relaxation of prohibitions of domestic propaganda in the United States.

Techniques

Anti-capitalist propaganda

Common media for transmitting propaganda messages include news reports, government reports, historical revision, junk science, books, leaflets, movies, radio, television, and posters. Some propaganda campaigns follow a strategic transmission pattern to indoctrinate the target group. This may begin with a simple transmission, such as a leaflet or advertisement dropped from a plane or an advertisement. Generally these messages will contain directions on how to obtain more information, via a web site, hot line, radio program, etc. (as it is seen also for selling purposes among other goals). The strategy intends to initiate the individual from information recipient to information seeker through reinforcement, and then from information seeker to opinion leader through indoctrination.

A number of techniques based in social psychological research are used to generate propaganda. Many of these same techniques can be found under logical fallacies, since propagandists use arguments that, while sometimes convincing, are not necessarily valid.

Some time has been spent analyzing the means by which the propaganda messages are transmitted. That work is important but it is clear that information dissemination strategies become propaganda strategies only when coupled with propagandistic messages. Identifying these messages is a necessary prerequisite to study the methods by which those messages are spread.

Models

Social psychology

Public reading of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, Worms, Germany, 1935

The field of social psychology includes the study of persuasion. Social psychologists can be sociologists or psychologists. The field includes many theories and approaches to understanding persuasion. For example, communication theory points out that people can be persuaded by the communicator's credibility, expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. The elaboration likelihood model as well as heuristic models of persuasion suggest that a number of factors (e.g., the degree of interest of the recipient of the communication), influence the degree to which people allow superficial factors to persuade them. Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Herbert A. Simon won the Nobel prize for his theory that people are cognitive misers. That is, in a society of mass information, people are forced to make decisions quickly and often superficially, as opposed to logically.

According to William W. Biddle's 1931 article "A psychological definition of propaganda", "[t]he four principles followed in propaganda are: (1) rely on emotions, never argue; (2) cast propaganda into the pattern of "we" versus an "enemy"; (3) reach groups as well as individuals; (4) hide the propagandist as much as possible."

Herman and Chomsky

Early 20th-century depiction of a "European Anarchist" attempting to destroy the Statue of Liberty

The propaganda model is a theory advanced by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky which argues systemic biases in the mass media and seeks to explain them in terms of structural economic causes:

The 20th century has been characterized by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power, and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.First presented in their 1988 book Manufacturing Consent: the Political Economy of the Mass Media, the propaganda model views the private media as businesses selling a product — readers and audiences (rather than news) — to other businesses (advertisers) and relying primarily on government and corporate information and propaganda. The theory postulates five general classes of "filters" that determine the type of news that is presented in news media: Ownership of the medium, the medium's Funding, Sourcing of the news, Flak, and anti-communist ideology.

The first three (ownership, funding, and sourcing) are generally regarded by the authors as being the most important. Although the model was based mainly on the characterization of United States media, Chomsky and Herman believe the theory is equally applicable to any country that shares the basic economic structure and organizing principles the model postulates as the cause of media bias.

Children

A 1938 propaganda of the New State depicting Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas

flanked by children. The text on the bottom right of this poster

translates as: "Children! Learning, at home and in school, the cult of

the Fatherland, you will bring all chances of success to life. Only love

builds and, strongly loving Brazil, you will lead it to the greatest of

destinies among Nations, fulfilling the desires of exaltation nestled

in every Brazilian heart."

Poster promoting the Nicaraguan Sandinistas.

The text reads: "Sandinista children: Toño, Delia and Rodolfo are in

the Association of Sandinista Children. Sandinista children use a neckerchief. They participate in the revolution and are very studious."

Of all the potential targets for propaganda, children are the most vulnerable because they are the least prepared with the critical reasoning and contextual comprehension they need to determine whether a message is propaganda or not. The attention children give their environment during development, due to the process of developing their understanding of the world, causes them to absorb propaganda indiscriminately. Also, children are highly imitative: studies by Albert Bandura, Dorothea Ross and Sheila A. Ross in the 1960s indicated that, to a degree, socialization, formal education and standardized television programming can be seen as using propaganda for the purpose of indoctrination. The use of propaganda in schools was highly prevalent during the 1930s and 1940s in Germany, as well as in Stalinist Russia. John Taylor Gatto asserts that modern schooling in the USA is designed to "dumb us down" in order to turn children into material suitable to work in factories. This ties into the Herman & Chomsky thesis of rise of Corporate Power, and its use in creating educational systems which serve its purposes against those of democracy.