| Brown v. Board of Education | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued December 9, 1952 Reargued December 8, 1953 Decided May 17, 1954 | |

| Full case name | Oliver Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al. |

| Citations | 347 U.S. 483

74 S. Ct. 686; 98 L. Ed. 873; 1954 U.S. LEXIS 2094; 53 Ohio Op. 326; 38 A.L.R.2d 1180

|

| Decision | Opinion |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for defendants, 98 F. Supp. 797 (D. Kan. 1951); probable jurisdiction noted, 344 U.S. 1 (1952). |

| Subsequent | Judgment on relief, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II); on remand, 139 F. Supp. 468 (D. Kan. 1955); motion to intervene granted, 84 F.R.D. 383 (D. Kan. 1979); judgment for defendants, 671 F. Supp. 1290 (D. Kan. 1987); reversed, 892 F.2d 851 (10th Cir. 1989); vacated, 503 U.S. 978 (1992) (Brown III); judgment reinstated, 978 F.2d 585 (10th Cir. 1992); judgment for defendants, 56 F. Supp. 2d 1212 (D. Kan. 1999) |

| Holding | |

| Segregation of students in public schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, because separate facilities are inherently unequal. District Court of Kansas reversed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. XIV | |

This case overturned a previous ruling or rulings

| |

| (partial) Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education (1899) Berea College v. Kentucky (1908) | |

Educational segregation in the US prior to Brown

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that American state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools

are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise

equal in quality. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Court's unanimous

(9–0) decision stated that "separate educational facilities are

inherently unequal," and therefore violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

However, the decision's 14 pages did not spell out any sort of method

for ending racial segregation in schools, and the Court's second

decision in Brown II (349 U.S. 294 (1955)) only ordered states to desegregate "with all deliberate speed".

The case originated in Topeka, Kansas, where the public school district had implemented a segregated school system for its elementary schools.

In 1951, the district refused to enroll the daughter of local resident

Oliver Brown at the school closest to their home, instead requiring her

to ride a bus to a segregated black elementary school further away. The

Browns and twelve other black Topeka families then filed a class action

lawsuit in U.S. federal court against the Topeka Board of Education,

alleging that the school district's segregation policy was

unconstitutional. A three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas rendered a verdict against the Browns based on the Supreme Court's precedent in the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson,

in which the Court had ruled that racial segregation was not in itself a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause if the

facilities in question were otherwise equal, a doctrine that had come to

be known as "separate but equal". The Browns, represented by NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case.

The Court's decision in Brown partially overruled Plessy v. Ferguson by declaring that the "separate but equal" notion was unconstitutional for American public schools and educational facilities. It paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the Civil Rights Movement, and a model for many future impact litigation cases. In the American South, especially the "Deep South", where racial segregation was deeply entrenched, the reaction to Brown among most white people was "noisy and stubborn". Many Southern governmental and political leaders embraced a plan known as "Massive Resistance", created by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd, in order to frustrate attempts to force them to de-segregate their school systems. Four years later, in the case of Cooper v. Aaron, the Court reaffirmed its ruling in Brown, and explicitly stated that state officials and legislators had no power to nullify its ruling.

Background

For much of the sixty years preceding the Brown case, race relations in the United States had been dominated by racial segregation. This policy had been endorsed in 1896 by the United States Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which held that as long as the separate facilities for the separate races were equal, segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment ("no State shall ... deny to any person ... the equal protection of the laws").

The plaintiffs in Brown asserted that this system of racial separation,

while masquerading as providing separate but equal treatment of both

white and black Americans, instead perpetuated inferior accommodations,

services, and treatment for black Americans. Racial segregation in

education varied widely from the 17 states that required racial

segregation to the 16 in which it was prohibited. Brown was influenced by UNESCO's 1950 Statement, signed by a wide variety of internationally renowned scholars, titled The Race Question. This declaration denounced previous attempts at scientifically justifying racism as well as morally condemning racism. Another work that the Supreme Court cited was Gunnar Myrdal's An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944). Myrdal had been a signatory of the UNESCO declaration.

The United States and the Soviet Union were both at the height of the Cold War

during this time, and U.S. officials, including Supreme Court Justices,

were highly aware of the harm that segregation and racism played on

America's international image. When Justice William O. Douglas traveled to India

in 1950, the first question he was asked was, "Why does America

tolerate the lynching of Negroes?" Douglas later wrote that he had

learned from his travels that "the attitude of the United States toward

its colored minorities is a powerful factor in our relations with

India." Chief Justice Earl Warren, nominated to the Supreme Court by President Eisenhower,

echoed Douglas's concerns in a 1954 speech to the American Bar

Association, proclaiming that "Our American system like all others is on

trial both at home and abroad, ... the extent to which we maintain the

spirit of our constitution with its Bill of Rights, will in the long run

do more to make it both secure and the object of adulation than the

number of hydrogen bombs we stockpile."

Case

Filing and arguments

In 1951, a class action suit was filed against the Board of Education of the City of Topeka, Kansas in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas. The plaintiffs were thirteen Topeka parents on behalf of their 20 children.

The suit called for the school district to reverse its policy of

racial segregation. The Topeka Board of Education operated separate

elementary schools due to a 1879 Kansas law, which permitted (but did

not require) districts to maintain separate elementary school facilities

for black and white students in 12 communities with populations over

15,000. The plaintiffs had been recruited by the leadership of the

Topeka NAACP. Notable among the Topeka NAACP leaders were the chairman McKinley Burnett; Charles Scott, one of three serving as legal counsel for the chapter; and Lucinda Todd.

The named plaintiff, Oliver Brown, was a parent, a welder in the shops of the Santa Fe Railroad, an assistant pastor at his local church, and an African American. He was convinced to join the lawsuit by Scott, a childhood friend. Brown's daughter Linda Carol Brown, a third grader, had to walk six blocks to her school bus stop to ride to Monroe Elementary, her segregated black school one mile (1.6 km) away, while Sumner Elementary, a white school, was seven blocks from her house.

As directed by the NAACP leadership, the parents each attempted

to enroll their children in the closest neighborhood school in the fall

of 1951. They were each refused enrollment and directed to the

segregated schools.

The case "Oliver Brown et al. v. The Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas" was named after Oliver Brown as a legal strategy to have

a man at the head of the roster. The lawyers, and the National Chapter

of the NAACP, also felt that having Mr. Brown at the head of the roster

would be better received by the U.S. Supreme Court Justices. The 13

plaintiffs were: Oliver Brown, Darlene Brown, Lena Carper, Sadie

Emmanuel, Marguerite Emerson, Shirley Fleming, Zelma Henderson, Shirley Hodison, Maude Lawton, Alma Lewis, Iona Richardson, and Lucinda Todd. The last surviving plaintiff, Zelma Henderson, died in Topeka, on May 20, 2008, at age 88.

The District Court ruled in favor of the Board of Education, citing the U.S. Supreme Court precedent set in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537

(1896), which had upheld a state law requiring "separate but equal"

segregated facilities for blacks and whites in railway cars. The three-judge District Court panel found that segregation in public education has a detrimental effect on negro

children, but denied relief on the ground that the negro and white

schools in Topeka were substantially equal with respect to buildings,

transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of teachers.

Supreme Court review

The case of Brown v. Board of Education as heard before the Supreme Court combined five cases: Brown itself, Briggs v. Elliott (filed in South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (filed in Virginia), Gebhart v. Belton (filed in Delaware), and Bolling v. Sharpe (filed in Washington, D.C.).

All were NAACP-sponsored cases. The Davis case, the only case of the five originating from a student protest, began when 16-year-old Barbara Rose Johns organized and led a 450-student walkout of Moton High School. The Gebhart case was the only one where a trial court, affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court,

found that discrimination was unlawful; in all the other cases the

plaintiffs had lost as the original courts had found discrimination to

be lawful.

The Kansas case was unique among the group in that there was no

contention of gross inferiority of the segregated schools' physical

plant, curriculum, or staff. The district court found substantial

equality as to all such factors. The lower court, in its opinion, noted

that, in Topeka, "the physical facilities, the curricula, courses of

study, qualification and quality of teachers, as well as other

educational facilities in the two sets of schools [were] comparable."

The lower court observed that "colored children in many instances are

required to travel much greater distances than they would be required to

travel could they attend a white school" but also noted that the school

district "transports colored children to and from school free of

charge" and that "no such service [was] provided to white children."

In the Delaware case the district court judge in Gebhart

ordered that the black students be admitted to the white high school due

to the substantial harm of segregation and the differences that made

the separate schools unequal.

The NAACP's chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall—who

was later appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967—argued the case

before the Supreme Court for the plaintiffs. Assistant attorney general

Paul Wilson—later distinguished emeritus professor of law at the University of Kansas—conducted the state's ambivalent defense in his first appellate argument.

In December 1952, the Justice Department filed a friend of the court brief in the case. The brief was unusual in its heavy emphasis on foreign-policy considerations of the Truman administration

in a case ostensibly about domestic issues. Of the seven pages covering

"the interest of the United States," five focused on the way school

segregation hurt the United States in the Cold War competition for the

friendship and allegiance of non-white peoples in countries then gaining

independence from colonial rule. Attorney General James P. McGranery noted that

The existence of discrimination against minority groups in the United States has an adverse effect upon our relations with other countries. Racial discrimination furnishes grist for the Communist propaganda mills.

The brief also quoted a letter by Secretary of State Dean Acheson lamenting that

The United States is under constant attack in the foreign press, over the foreign radio, and in such international bodies as the United Nations because of various practices of discrimination in this country.

British barrister and parliamentarian Anthony Lester has written that "Although the Court's opinion in Brown

made no reference to these considerations of foreign policy, there is

no doubt that they significantly influenced the decision."

Consensus building

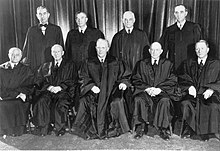

The

members of the U.S. Supreme Court that on May 17, 1954, ruled

unanimously that racial segregation in public schools is

unconstitutional.

In spring 1953, the Court heard the case but was unable to decide the

issue and asked to rehear the case in fall 1953, with special attention

to whether the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause

prohibited the operation of separate public schools for whites and

blacks.

The Court reargued the case at the behest of Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter, who used reargument as a stalling tactic, to allow the Court to gather a consensus around a Brown

opinion that would outlaw segregation. The justices in support of

desegregation spent much effort convincing those who initially intended

to dissent to join a unanimous opinion. Although the legal effect would

be same for a majority rather than unanimous decision, it was felt that

dissent could be used by segregation supporters as a legitimizing

counter-argument.

Conference notes and draft decisions illustrate the division of opinions before the decision was issued. Justices Douglas, Black, Burton, and Minton were predisposed to overturn Plessy. Fred M. Vinson noted that Congress had not issued desegregation legislation; Stanley F. Reed discussed incomplete cultural assimilation and states' rights and was inclined to the view that segregation worked to the benefit of the African-American community; Tom C. Clark wrote that "we had led the states on to think segregation is OK and we should let them work it out." Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson disapproved of segregation, but were also opposed to judicial activism and expressed concerns about the proposed decision's enforceability. Chief Justice Vinson had been a key stumbling block. After Vinson died in September 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren as Chief Justice. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American students in California school systems following Mendez v. Westminster. However, Eisenhower invited Earl Warren to a White House

dinner, where the president told him: "These [southern whites] are not

bad people. All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet

little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big

overgrown Negroes." Nevertheless, the Justice Department sided with the

African American plaintiffs.

While all but one justice personally rejected segregation, the judicial restraint

faction questioned whether the Constitution gave the Court the power to

order its end. The activist faction believed the Fourteenth Amendment

did give the necessary authority and were pushing to go ahead. Warren,

who held only a recess appointment, held his tongue until the Senate confirmed his appointment.

Warren convened a meeting of the justices, and presented to them

the simple argument that the only reason to sustain segregation was an

honest belief in the inferiority of Negroes. Warren further submitted

that the Court must overrule Plessy to maintain its legitimacy as an institution of liberty, and it must do so unanimously to avoid massive Southern

resistance. He began to build a unanimous opinion. Although most

justices were immediately convinced, Warren spent some time after this

famous speech convincing everyone to sign onto the opinion. Justice

Jackson dropped his concurrence and Reed finally decided to drop his

dissent. The final decision was unanimous. Warren drafted the basic

opinion and kept circulating and revising it until he had an opinion

endorsed by all the members of the Court. Reed was the last holdout and reportedly cried during the reading of the opinion.

Decision

On May 17, 1954, the Court issued a unanimous 9–0 decision in favor

of the Brown family and the other plaintiffs. The decision consists of a

single opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, which all the justices joined.

The Court's opinion began by noting that it had attempted to find an answer to the question of whether the Fourteenth Amendment

was meant to abolish segregation in public education by hearing a

second round of oral arguments from the parties' lawyers specifically on

the historical sources relating to its drafting and ratification, but

to no avail.

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive.

— Brown, 347 U.S. at 489.

The Court also stated that using historical information on the

original scope of the Fourteenth Amendment's application to public

education was difficult because of intervening societal and governmental

changes.

It noted that in 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, public schools

were uncommon in the American South. White children whose families could

afford schooling usually attended private schools, and the education of

black children was "almost nonexistent", to the point that in some

Southern states any education of black people had actually been

forbidden by law.

The Court contrasted this with the situation in 1954: "Today, education

is perhaps the most important function of our local and state

governments."

It concluded that, in making its ruling, the Court would have to

"consider public education in light of its full development and its

present place in American life throughout the Nation."

The Court did not address the issues regarding the many instances

in which the segregated educational facilities for black children in

the cases were inferior in quality to those for white children, probably

because some of the school districts involved had made improvements to

their black schools to "equalize" them with the quality of the white

schools. This prevented the Court from finding a violation of the Equal Protection Clause

in "measurable inequalities" between all white and black schools, and

instead required it to look to the effects of segregation itself.

Thus, the Court framed the case around the more general question of

whether the principle of "separate but equal" was constitutional when

applied to public education:

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities?

— Brown, 397 U.S. at 493.

In answer, the Court ruled that it did.

It held that state-mandated segregation, even if implemented in schools

of otherwise equal quality, is inherently unequal: "To separate [black

children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because

of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in

the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely

to ever be undone."

The Court supported this conclusion with citations—in a footnote, not

the main text of the opinion—to a number of psychology studies that

purported to show that segregating black children made them feel

inferior and interfered with their learning. These studies included those of Kenneth and Mamie Clark, whose experiments in the 1940s had suggested that black children from segregated environments preferred white dolls over black dolls.

The Court then concluded its relatively short opinion by

declaring that segregated public education was inherently unequal,

violated the Equal Protection Clause, and therefore was unconstitutional:

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

— Brown, 397 U.S. at 495.

The Court did not close with an order to implement the remedy of

integrating the schools of the various jurisdictions, but instead

requested the parties to re-appear before the Court the following Term

in order to hold arguments on the issue. This became the case known as Brown II, described below.

Reaction and aftermath

Although many Americans cheered the Court's decision, most Southern

whites decried it, and progress on integrating American schools moved

slowly. Many viewed Brown v. Board of Education as "a day of catastrophe — a Black Monday — a day something like Pearl Harbor". The American political historian Robert G. McCloskey wrote of the South's anger with the decision and its slow effects:

The reaction of the white South to this judicial onslaught on its institutions was noisy and stubborn. Certain “border states,” which had formerly maintained segregated school systems, did integrate, and others permitted the token admission of a few Negro students to schools that had once been racially unmixed. However, the Deep South made no moves to obey the judicial command, and in some districts there can be no doubt that the Desegregation decision hardened resistance to integration proposals.

— McCloskey & Levinson (2010), p. 144.

In Virginia, Senator Harry F. Byrd organized the Massive Resistance movement that included the closing of schools rather than desegregating them.

Deep South

Texas Attorney General John Ben Shepperd organized a campaign to generate legal obstacles to implementation of desegregation.

In 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out his state's National Guard to block black students' entry to Little Rock Central High School. President Dwight Eisenhower responded by deploying elements of the 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, to Arkansas and by federalizing Arkansas's National Guard.

Also in 1957, Florida's response was mixed. Its legislature passed an Interposition Resolution denouncing the decision and declaring it null and void. But Florida Governor LeRoy Collins,

though joining in the protest against the court decision, refused to

sign it, arguing that the attempt to overturn the ruling must be done by

legal methods.

In Mississippi fear of violence prevented any plaintiff from bringing a school desegregation suit for the next nine years.[48] When Medgar Evers sued to desegregate Jackson, Mississippi schools in 1963 White Citizens Council member Byron De La Beckwith murdered him. Two subsequent trials resulted in hung juries. Beckwith was not convicted of the murder until 1994.

In 1963, Alabama Gov. George Wallace personally blocked the door to Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama to prevent the enrollment of two black students. This became the infamous Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

where Wallace personally backed his "segregation now, segregation

tomorrow, segregation forever" policy that he had stated in his 1963

inaugural address. He moved aside only when confronted by General Henry Graham of the Alabama National Guard, who was ordered by President John F. Kennedy to intervene.

Native American communities were also heavily impacted by

segregation laws with native children also being prohibited from

attending white institutions.

Native American children considered light-complexioned were allowed to

ride school buses to previously all white schools, while dark-skinned

Native children from the same band were still barred from riding the

same buses.

Tribal leaders, learned about Dr. King's desegregation campaign in

Birmingham, Alabama, contacted him for assistance. King promptly

responded to the tribal leaders and through his intervention the problem

was quickly resolved.

Upland South

In North Carolina, there was often a strategy of nominally accepting Brown, but tacitly resisting it. On May 18, 1954 the Greensboro, North Carolina school board declared that it would abide by the Brown

ruling. This was the result of the initiative of D. E. Hudgins Jr., a

former Rhodes Scholar and prominent attorney, who chaired the school

board. This made Greensboro the first, and for years the only, city in

the South, to announce its intent to comply. However, others in the city

resisted integration, putting up legal obstacles

to the actual implementation of school desegregation for years

afterward, and in 1969, the federal government found the city was not in

compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Transition to a fully

integrated school system did not begin until 1971, after numerous local

lawsuits and both nonviolent and violent demonstrations. Historians have

noted the irony that Greensboro, which had heralded itself as such a

progressive city, was one of the last holdouts for school desegregation.

In Moberly, Missouri,

the schools were desegregated, as ordered. However, after 1955, the

African-American teachers from the local "negro school" were not

retained; this was ascribed to poor performance. They appealed their

dismissal in Naomi Brooks et al., Appellants, v. School District of City of Moberly, Missouri, Etc., et al.; but it was upheld, and SCOTUS declined to hear a further appeal.

North

Many Northern cities also had de facto segregation policies, which resulted in a vast gulf in educational resources between black and white communities. In Harlem,

New York, for example, not a single new school had been built since the

turn of the century, nor did a single nursery school exist, even as the

Second Great Migration

caused overcrowding of existing schools. Existing schools tended to be

dilapidated and staffed with inexperienced teachers. Northern officials

were in denial of the segregation, but Brown helped stimulate activism among African-American parents like Mae Mallory who, with support of the NAACP, initiated a successful lawsuit against the city and State of New York on Brown's

principles. Mallory and thousands of other parents bolstered the

pressure of the lawsuit with a school boycott in 1959. During the

boycott, some of the first freedom schools

of the period were established. The city responded to the campaign by

permitting more open transfers to high-quality, historically-white

schools. (New York's African-American community, and Northern

desegregation activists generally, now found themselves contending with

the problem of white flight, however.)

Topeka

Judgment and order of the Supreme Court for the case.

The Topeka junior high schools had been integrated since 1941. Topeka

High School was integrated from its inception in 1871 and its sports

teams from 1949 on. The Kansas law permitting segregated schools allowed them only "below the high school level".

Soon after the district court decision, election outcomes and the

political climate in Topeka changed. The Board of Education of Topeka

began to end segregation in the Topeka elementary schools in August

1953, integrating two attendance districts. All the Topeka elementary

schools were changed to neighborhood attendance centers in January 1956,

although existing students were allowed to continue attending their

prior assigned schools at their option.

Plaintiff Zelma Henderson, in a 2004 interview, recalled that no

demonstrations or tumult accompanied desegregation in Topeka's schools:

"They accepted it," she said. "It wasn't too long until they integrated the teachers and principals."

The Topeka Public Schools administration building is named in honor of McKinley Burnett, NAACP chapter president who organized the case.

Monroe Elementary was designated a U.S. National Historic Site unit of the National Park Service on October 26, 1992.

The intellectual roots of Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark United States Supreme Court decision upholding the constitutionality of racial segregation in 1896 under the doctrine of "separate but equal" were, in part, tied to the scientific racism of the era. However, the popular support for the decision was more likely a result of the racist beliefs held by many whites at the time. In deciding Brown v. Board of Education,

the Supreme Court rejected the ideas of scientific racists about the

need for segregation, especially in schools. The Court buttressed its

holding by citing social science research about the harms to black children caused by segregated schools.

Both scholarly and popular ideas of hereditarianism played an important role in the attack and backlash that followed the Brown decision. The Mankind Quarterly was founded in 1960, in part in response to the Brown decision.

Legal criticism and praise

U.S. circuit judges Robert A. Katzmann, Damon J. Keith, and Sonia Sotomayor at a 2004 exhibit on the Fourteenth Amendment, Thurgood Marshall, and Brown v. Board of Education

William Rehnquist wrote a memo titled "A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases" when he was a law clerk for Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1952, during early deliberations that led to the Brown v. Board of Education

decision. In his memo, Rehnquist argued: "I realize that it is an

unpopular and unhumanitarian position, for which I have been excoriated

by 'liberal' colleagues but I think Plessy v. Ferguson

was right and should be reaffirmed." Rehnquist continued, "To the

argument . . . that a majority may not deprive a minority of its

constitutional right, the answer must be made that while this is sound

in theory, in the long run it is the majority who will determine what

the constitutional rights of the minorities are." Rehnquist also argued for Plessy with other law clerks.

However, during his 1971 confirmation hearings, Rehnquist said,

"I believe that the memorandum was prepared by me as a statement of

Justice Jackson's tentative views for his own use." Justice Jackson had

initially planned to join a dissent in Brown.

Later, at his 1986 hearings for the slot of Chief Justice, Rehnquist

put further distance between himself and the 1952 memo: "The bald

statement that Plessy was right and should be reaffirmed, was not an

accurate reflection of my own views at the time."

In any event, while serving on the Supreme Court, Rehnquist made no effort to reverse or undermine the Brown decision, and frequently relied upon it as precedent.

Chief Justice Warren's reasoning was broadly criticized by contemporary legal academics with Judge Learned Hand decrying that the Supreme Court had "assumed the role of a third legislative chamber" and Herbert Wechsler finding Brown impossible to justify based on neutral principles.

Some aspects of the Brown decision are still debated. Notably, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, himself an African American, wrote in Missouri v. Jenkins (1995) that at the very least, Brown I has been misunderstood by the courts.

Brown I did not say that "racially isolated" schools were inherently inferior; the harm that it identified was tied purely to de jure segregation, not de facto segregation. Indeed, Brown I itself did not need to rely upon any psychological or social-science research in order to announce the simple, yet fundamental truth that the Government cannot discriminate among its citizens on the basis of race. …

Segregation was not unconstitutional because it might have caused psychological feelings of inferiority. Public school systems that separated blacks and provided them with superior educational resources making blacks "feel" superior to whites sent to lesser schools—would violate the Fourteenth Amendment, whether or not the white students felt stigmatized, just as do school systems in which the positions of the races are reversed. Psychological injury or benefit is irrelevant …

Given that desegregation has not produced the predicted leaps forward in black educational achievement, there is no reason to think that black students cannot learn as well when surrounded by members of their own race as when they are in an integrated environment. (…) Because of their "distinctive histories and traditions," black schools can function as the center and symbol of black communities, and provide examples of independent black leadership, success, and achievement.

Some Constitutional originalists, notably Raoul Berger in his influential 1977 book "Government by Judiciary," make the case that Brown cannot be defended by reference to the original understanding of the 14th Amendment. They support this reading of the 14th amendment by noting that the Civil Rights Act of 1875

did not ban segregated schools and that the same Congress that passed

the 14th Amendment also voted to segregate schools in the District of

Columbia. Other originalists, including Michael W. McConnell, a federal judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, in his article "Originalism and the Desegregation Decisions," argue that the Radical Reconstructionists who spearheaded the 14th Amendment were in favor of desegregated southern schools.

Evidence supporting this interpretation of the 14th amendment has come

from archived Congressional records showing that proposals for federal

legislation which would enforce school integration were debated in

Congress a few years following the amendment's ratification.

In response to Michael McConnell's research, Raoul Berger argued that

the Congressmen and Senators who were advocating in favor of school

desegregation in the 1870s were trying to rewrite the 14th Amendment (in

order to make the 14th Amendment fit their political agenda) and that

the actual understanding of the 14th Amendment from 1866 to 1868 (which

is when the 14th Amendment was actually passed and ratified) does, in

fact, permit U.S. states to have segregated schools.

The case also has attracted some criticism from more liberal

authors, including some who say that Chief Justice Warren's reliance on

psychological criteria to find a harm against segregated blacks was

unnecessary. For example, Drew S. Days has written:

"we have developed criteria for evaluating the constitutionality of

racial classifications that do not depend upon findings of psychic harm

or social science evidence. They are based rather on the principle that

'distinctions between citizens solely because of their ancestry are by

their very nature odious to a free people whose institutions are founded

upon the doctrine of equality,' Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943). . . ."

In his book The Tempting of America (page 82), Robert Bork endorsed the Brown decision as follows:

By 1954, when Brown came up for decision, it had been apparent for some time that segregation rarely if ever produced equality. Quite aside from any question of psychology, the physical facilities provided for blacks were not as good as those provided for whites. That had been demonstrated in a long series of cases … The Court's realistic choice, therefore, was either to abandon the quest for equality by allowing segregation or to forbid segregation in order to achieve equality. There was no third choice. Either choice would violate one aspect of the original understanding, but there was no possibility of avoiding that. Since equality and segregation were mutually inconsistent, though the ratifiers did not understand that, both could not be honored. When that is seen, it is obvious the Court must choose equality and prohibit state-imposed segregation. The purpose that brought the fourteenth amendment into being was equality before the law, and equality, not separation, was written into the law.

In June 1987, Philip Elman,

a civil rights attorney who served as an associate in the Solicitor

General's office during Harry Truman's term, claimed he and Associate

Justice Felix Frankfurter were mostly responsible for the Supreme

Court's decision, and stated that the NAACP's arguments did not present

strong evidence.

Elman has been criticized for offering a self-aggrandizing history of

the case, omitting important facts, and denigrating the work of civil

rights attorneys who had laid the groundwork for the decision over many

decades. However, Frankfurter was also known for being one of court's most outspoken advocates of the judicial restraint philosophy of basing court rulings on existing law rather than personal or political considerations.

Public officials in the United States today are nearly unanimous in

lauding the ruling. In May 2004, the fiftieth anniversary of the ruling,

President George W. Bush spoke at the opening of the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, calling Brown "a decision that changed America for the better, and forever." Most Senators and Representatives issued press releases hailing the ruling.

In an article in Townhall, Thomas Sowell argued that when Chief Justice Earl Warren declared in the landmark 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education that racially separate schools were "inherently unequal," Dunbar High School was a living refutation of that assumption. And it was within walking distance of the Supreme Court."

Brown II

In 1955, the Supreme Court considered arguments by the schools

requesting relief concerning the task of desegregation. In their

decision, which became known as "Brown II"

the court delegated the task of carrying out school desegregation to

district courts with orders that desegregation occur "with all

deliberate speed," a phrase traceable to Francis Thompson's poem, "The Hound of Heaven".

Supporters of the earlier decision were displeased with this

decision. The language "all deliberate speed" was seen by critics as too

ambiguous to ensure reasonable haste for compliance with the court's

instruction. Many Southern states and school districts interpreted

"Brown II" as legal justification for resisting, delaying, and avoiding

significant integration for years—and in some cases for a decade or

more—using such tactics as closing down school systems, using state

money to finance segregated "private" schools, and "token" integration

where a few carefully selected black children were admitted to former

white-only schools but the vast majority remained in underfunded,

unequal black schools.

For example, based on "Brown II," the U.S. District Court ruled that Prince Edward County, Virginia

did not have to desegregate immediately. When faced with a court order

to finally begin desegregation in 1959 the county board of supervisors

stopped appropriating money for public schools, which remained closed

for five years, from 1959 to 1964.

White students in the county were given assistance to attend

white-only "private academies" that were taught by teachers formerly

employed by the public school system, while black students had no

education at all unless they moved out of the county. But the public

schools reopened after the Supreme Court overturned "Brown II" in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

declaring that "...the time for mere 'deliberate speed' has run out,"

and that the county must provide a public school system for all children

regardless of race.

Brown III

In 1978, Topeka attorneys Richard Jones, Joseph Johnson and Charles Scott, Jr. (son of the original Brown team member), with assistance from the American Civil Liberties Union, persuaded Linda Brown Smith—who now had her own children in Topeka schools—to be a plaintiff in reopening Brown.

They were concerned that the Topeka Public Schools' policy of "open

enrollment" had led to and would lead to further segregation. They also

believed that with a choice of open enrollment, white parents would

shift their children to "preferred" schools that would create both

predominantly African American and predominantly European American

schools within the district. The district court reopened the Brown

case after a 25-year hiatus, but denied the plaintiffs' request finding

the schools "unitary". In 1989, a three-judge panel of the Tenth Circuit on 2–1 vote found that the vestiges of segregation remained with respect to student and staff assignment. In 1993, the Supreme Court denied the appellant School District's request for certiorari and returned the case to District Court Judge Richard Rodgers for implementation of the Tenth Circuit's mandate.

After a 1994 plan was approved and a bond issue passed,

additional elementary magnet schools were opened and district attendance

plans redrawn, which resulted in the Topeka schools meeting court

standards of racial balance by 1998. Unified status was eventually

granted to Topeka Unified School District No. 501 on July 27, 1999. One of the new magnet schools is named after the Scott family attorneys for their role in the Brown case and civil rights.

Other comments

A PBS film called "Simple Justice" retells the story of the Brown vs.

Board of Education case, beginning with the work of the NAACP's Legal

Defense Fund's efforts to combat 'separate but equal' in graduate school

education and culminating in the historical 1954 decision.

Linda Brown Thompson later recalled the experience of being refused enrollment:

...we lived in an integrated neighborhood and I had all of these playmates of different nationalities. And so when I found out that day that I might be able to go to their school, I was just thrilled, you know. And I remember walking over to Sumner school with my dad that day and going up the steps of the school and the school looked so big to a smaller child. And I remember going inside and my dad spoke with someone and then he went into the inner office with the principal and they left me out ... to sit outside with the secretary. And while he was in the inner office, I could hear voices and hear his voice raised, you know, as the conversation went on. And then he immediately came out of the office, took me by the hand and we walked home from the school. I just couldn't understand what was happening because I was so sure that I was going to go to school with Mona and Guinevere, Wanda, and all of my playmates.

Linda Brown died on March 25, 2018 at the age of 76.