The History of Transcendental Meditation (TM) and the Transcendental Meditation movement originated with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, founder of the organization, and continues beyond his death (2008). In 1955, the Maharishi began publicly teaching a traditional meditation technique learned from his master Brahmananda Saraswati, which he called Transcendental Deep Meditation, and later renamed Transcendental Meditation.

The Maharishi initiated thousands of people, then developed a TM teacher training program as a way to accelerate the rate of bringing the technique to more people. He also inaugurated a series of world tours which promoted Transcendental Meditation. These factors, coupled with endorsements by celebrities who practiced TM, along with scientific research that validated the technique, helped to popularize TM in the 1960s and 1970s. By the late 2000s, TM had been taught to millions of individuals and the Maharishi was overseeing a large multinational movement. Despite organizational changes and the addition of advanced meditative techniques in the 1970s the Transcendental Meditation technique has remained relatively unchanged.

Among the first organizations to promote TM were the Spiritual Regeneration Movement and the International Meditation Society. In present times, the movement has grown to encompass schools and universities that teach the practice, and includes many associated programs offering health and well-being based on the Maharishi's interpretation of the Vedic traditions. In the U.S., major organizations included Students International Meditation Society, AFSCI, World Plan Executive Council, Maharishi Vedic Education Development Corporation, and Global Country of World Peace. The successor to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and head of the Global Country of World Peace, is Tony Nader.

The Maharishi initiated thousands of people, then developed a TM teacher training program as a way to accelerate the rate of bringing the technique to more people. He also inaugurated a series of world tours which promoted Transcendental Meditation. These factors, coupled with endorsements by celebrities who practiced TM, along with scientific research that validated the technique, helped to popularize TM in the 1960s and 1970s. By the late 2000s, TM had been taught to millions of individuals and the Maharishi was overseeing a large multinational movement. Despite organizational changes and the addition of advanced meditative techniques in the 1970s the Transcendental Meditation technique has remained relatively unchanged.

Among the first organizations to promote TM were the Spiritual Regeneration Movement and the International Meditation Society. In present times, the movement has grown to encompass schools and universities that teach the practice, and includes many associated programs offering health and well-being based on the Maharishi's interpretation of the Vedic traditions. In the U.S., major organizations included Students International Meditation Society, AFSCI, World Plan Executive Council, Maharishi Vedic Education Development Corporation, and Global Country of World Peace. The successor to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and head of the Global Country of World Peace, is Tony Nader.

1950s

In 1955, Brahmachari Mahesh left Uttarkashi and began publicly teaching what he stated was a traditional meditation technique learned from his master Brahmananda Saraswati, which he called Transcendental Deep Meditation. Later the technique was renamed Transcendental Meditation.

In 1958, Brahmachari Mahesh, now called Maharishi Mahesh Yogi,

began a number of worldwide tours promoting and disseminating

Transcendental Meditation. The first tour began in Rangoon, Burma (now Myanmar). The Maharishi remained in the Far East for about six months teaching his meditation.

In 1959, the Maharishi taught the Transcendental Meditation technique in Hawaii, San Francisco, Los Angeles, London and Germany. He founded the Spiritual Regeneration Movement in Los Angeles, in 1959 and established an office there, which was the only place where TM was taught in the USA between 1959 and 1965.

1960s

In 1960,

the Maharishi founded the International Meditation Society (IMS) and

trained his first TM teacher, Henry Nyburg of England.

During the tour Maharishi made Henry Nyburg his personal representative

in Europe and gave him the training and authority to teach

Transcendental Meditation, thus making him the first European teacher.

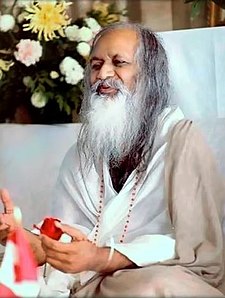

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

On 13 March 1961, a meeting called "1961 World Congress" was organised for the Maharishi in the Royal Albert Hall by Leon MacLaren of The School of Economic Science and Dr Frances Roles of the Study Society. Two smaller meetings were held at Caxton Hall prior to the main event.The Royal Albert Hall meeting was attended by 5,000 people. The School of Economic Science was instrumental in promoting TM in the UK from the 1960s.

In collaboration with The Study Society and the School of Economic Science, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi established The School of Meditation in London in 1961,

under the direction of Bill Whiting its purpose was, and remains, to

study and teach the principles and practical application of meditation. Many of the subsequent leaders of The School of Meditation were students of the Maharishi.

The School of Meditation is now an independent, self-governing

organisation. By 2011, SoM had initiated 15,332 people into the practice

of meditation, it has branches in several parts of the UK as well as in

Greece and Holland.

The Maharishi lectured at Caxton Hall in London and the talk was attended by Leon MacLaren. In the 1950s, he first TM teacher in the U.S. was a who was joined by a male instructor in 1966.

The first international Teacher Training Course (TTC) was held near Rishikesh, India, in 1961, to train teachers of Transcendental Meditation. Over 60 meditators from India, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Britain, Malaya, Norway, the United States, Australia, Greece, Italy and the West Indies attended the course. Teachers continued to be trained as time progressed and by 1978, there were 7,000 TM teachers in the U.S alone. The Maharishi appeared on BBC television and gave a lecture to 5,000 people at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 1974.

According to a history written by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 21 members of the Indian Parliament issued a public statement endorsing TM in 1963. According to the Maharishi, news articles on the technique appeared in Canadian newspapers such as the Daily Colonist, Calgary Herald and The Albertan.

The Students International Meditation Society (SIMS) began in Germany in 1964, was incorporated in the USA in 1965 and continues to function in some countries. Another organization, the American Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence (AFSC) taught TM to business people at Connecticut General Life Insurance Co., General Foods, Blue Cross/Blue Shield and AT&T. In 1967, the TM movement "really took off" when the Maharishi became the "spiritual advisor to The Beatles".

In 1968, the Maharishi announced that he would stop his "public

activities" and instead begin the training of TM teachers at his new

global headquarters in Seelisberg, Switzerland.

1970s

In 1970, the Maharishi held a TM teacher training course at a Victorian hotel located in Poland Springs, Maine with 1,200 participants. Later that year, he held a similar four-week course at Humboldt State College in Arcata, California. About 1,500 people attended and the course was described as a "sort of a crash program to train transcendental teachers". Following tax troubles in India, the Maharishi moved his headquarters to Italy and then to Austria.

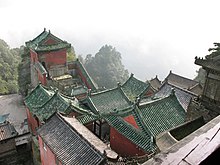

Maharishi University in Seelisberg

In 1970, the first scientific study on the Transcendental Meditation technique was published in the journal Science. In the early 1970s, courses on the Science of Creative Intelligence, Maharishi's unified theory of life,

were offered at universities such as Stanford University, Yale, the

University of Colorado, the University of Wisconsin, and Oregon State

University.

In 1972 in Mallorca,

Spain, the Maharishi announced his World Plan to establish one

Transcendental Meditation teaching center for each million of the

world's population.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the TM movement began to shed its

identity as part of the hippie counterculture, making incursions into

the US American cultural mainstream. From the mid-1970s, the Maharishi

began to target business professionals, adapting his message to promise

"increased creativity and flexibility, increased productivity, improved

job satisfaction, improved relations with supervisors and co-workers".

His TM movement came to be increasingly structured along the lines of a

multinational corporation. The Maharishi International University was founded in 1974 in Goleta California.

In 1975, Maharishi European University was found in Lake Lucerne Switzerland. That year TM practitioner Merv Griffin

invited the Maharishi to appear on his talk show, thereby aiding

Transcendental Meditation in becoming a "full blown craze" during that

era (according to Time Magazine) and in eventually becoming a global

phenomenon with centers in some 130 countries. In 1975 Transcendental Meditation received favorable testimony in the Congressional Record and was advocated by Major-General Franklin M. Davis Jr. of the US Army. Maharishi appeared on the Merv Griffin Show again in 1977.

In 1975, the Maharishi began teaching advanced mental techniques, called the TM-Sidhi Program, which included a technique for the development of what he termed Yogic Flying. The program was said to create the Maharishi Effect, based on studies which reported that in US cities where 1 percent of the population meditated, the crime rate dropped.

As early as 1968, the Maharishi stated that 30 minutes of TM morning

and evening by 1 percent of the population would "dispel the clouds of

war for thousands of years."

In 1976 the headquarters of the US movement moved to the former Santa Ynez Inn, a block from the ocean in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles and published a seven-hundred-page compilation of Transcendental Meditation research, generated by 51 institutions from 13 countries.

A Gallup Poll conducted in August 1976 said that four percent (4 percent) of those Americans questioned had engaged in TM. This was despite the fact that, according to movement records, only .5 percent of Americans had been initiated.

The average number of people learning TM fell from a peak of

approximately 40,000 a month in 1975 to approximately 3,000 in November

1977. William Sims Bainbridge

wrote that, as of 1977, "Most of the million who had been initiated

either ceased meditating or did so informally and irregularly without

continuing connections to the TM Movement."

The Maharishi Foundation in the UK purchased the historic Mentmore Towers

in 1978 for £240,000 for use as a headquarters and college. The stately

home, on 81 acres, was built in 1855 and had 60 bedrooms. A spokesman

said that repairs could be done cheaply by students in exchange for

meditation classes. It was the headquarters of the Natural Law Party and campus of Maharishi University of Natural Law. By 1997, the movement was seeking a larger facility and placed the home on the market for £10 million. It sold two years later for £3 million. During this period the Maharishi's personal residence and international headquarters were located in Seelisberg, Switzerland, in a former hotel on the shore of Lake Lucerne.

In 1979, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the 1977 decision of the US District Court

of New Jersey stating that a course in Transcendental Meditation and

the Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI) was religious activity within

the meaning of the Establishment Clause and that the teaching of SCI/TM in the New Jersey public high schools was prohibited by the First Amendment.

At that time, according to Humes, the movement directed itself

inward, offering additional products and practices to its committed

practitioners beyond Transcendental Meditation in order to help them

achieve Cosmic Consciousness.

According to Bainbridge, the most dedicated movement members were TM

teachers whose financial and social status depended on a flow of new

students. After the number of new initiations collapsed those teachers

lost the promise of success and the movement increasingly emphasized

unusual supernatural compensators.

During this period, the movement began making increasing claims about

the powers of TM and the TM-Sidhi program, including the reduction of

crime by the practice of "Yogic flying". According to Nancy Cooke de Herrera, an early teacher of TM and a TM-Sidhi practitioner, Charlie Lutes, former President of the Spiritual Regeneration Movement,

saw the introduction of the TM-Sidhi program as a financial ploy to

increase income in the wake of declining public interest in TM.

In England, the Maharishi Foundation bought Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire, Roydon Hall in Maidstone, Swythamley Park in the Peak District and a Georgian rectory in Suffolk, and his income was reported at six million GBP per year in 2008.

1980s

In 1984, about 1,200 members of the movement moved into Manila at the invitation of Ferdinand Marcos, the President of the Philippines. They named him the president and founding father of the Unified Field Based Civilization.

Marcos praised Maharishi's plan to use the Philippines as the base for

"this new kingdom of enlightenment" and, in a public ceremony, rang the

"Maharishi bell". Imelda Marcos was given the "crown of consciousness of the royal order of the age of enlightenment".

The members rented an entire floor of Manila's finest hotel, along with

hundreds of rooms in other hotels. They bought a large but financially

troubled university, the University of the East, for $1 million, leading to a boycott by students and attacks on the Maharishi as an imperialist.

A government cabinet member reported that the movement members had

deposited millions of dollars in Philippine bank accounts and were

negotiating to buy several more colleges and universities in the area,

plus hotels and other buildings. Posters promoting the benefits of

Transcendental Meditation were posted across the city and the members

spread out across the city to promote the technique, leading to a

response from Catholic Cardinal Jaime Sin. The movement took responsibility for the lack of violence at a large anti-government rally protesting the assassination of Benigno Aquino, but not for violent attacks by the military on rioters, two typhoons, or an eruption of Mount Mayon, which also occurred during their stay.

The University of the East was purchased back by its stakeholders, and

the movement characterized the entire transaction as a $250,000 loan.

In the 1980s the TM movement's US national offices and the

Maharishi International University College of Natural Law were located

in Washington D.C. five blocks from the White House.

From 1981 to 1987 this was also the location for the organization's

"administrative headquarters" for North America as well as a national

organization of 6,000 American medical doctors who practiced TM, a

private school, a clinic, and a TM meditation center. In 1991, The Washington Post

reported that the Maharishi, referring to Washington DC, had advised TM

practitioners: "save yourself from the criminal atmosphere". As a

result, 20 to 40 TM practitioners put their homes up for sale in an

effort to move away from the city. According to the Sunday Times,

the movement continued to expand during this period despite accusations

of fraud by former practitioners and claims that extraordinary powers

could be gained through TM and its advance programs.

TM teachers began teaching meditation in Romania in 1982, Poland in 1985 and in Yugoslavia in 1987.

1990s

In 1990, a delegation of Transcendental Meditation teachers from Maharishi International University traveled to the former Soviet Union

to provide instruction in Transcendental Meditation. The trip,

initially scheduled to last ten days, was extended to six months and

resulted in the training of 35,000 people in the technique.

In 1990, the Maharishi moved his headquarters to MERU, Holland, a wooded area outside of Vlodrop, Netherlands, near the German border. The 65-acre (260,000 m2) grounds of a former monastery became the capital of his Global Country of World Peace (GCWP).

The late dictator of Romania, Nicolae Ceaușescu, tried to purge all practitioners of transcendental meditation from the

government.

In 1993, the Maharishi Vedic Education Development Corporation

(MVED), a non-profit corporation, was formed to oversee the teaching of

Transcendental Meditation and related courses in the United States.

The terms "Transcendental Meditation" and "TM" are service marks owned

by Maharishi Foundation Ltd., a UK non-profit organization and licensed to the MVED.

In 1993 Maharishi Vedic University awarded an honorary doctorate degree

to then newly reelected President Joaquim Chissano. In his acceptance

speech, Chissano said he credited TM as being the source of all positive

changes in his country. he said the results of inviting the Maharishi to Maputo in 1992 were balance and peace. Maharishi called Chissano "a guiding light for all heads of state".

In 1995, the Maharishi changed the name of Maharishi International University in Fairfield, Iowa to Maharishi University of Management.

Maharishi Centre for Educational Excellence, Bhopal, India.

The Maharishi Vidya Mandir Schools (MVMS), an educational system established in 16 Indian states and affiliated with the New Delhi Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), was founded the same year.

Maharishi Vidya Mandir Schools has 148 branches in 118 cities with

90,000 to 100,000 students and 5,500 teaching and support staff.

By 1998, the global TM organization had an estimated four million

disciples, 1,000 teaching centers and property assets valued at $3.5

billion.

2000s

Meditation chambers at the former Academy of Meditation in Rishikesh, now owned by the Indian Government.

In 2004, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi directed Transcendental Meditation practitioners at the Maharishi village at Skelmersdale, Lancashire in England to beam peace-loving thoughts to the British electorate with the aim of overturning the Labour government.

The Maharishi said: "The good effects of transcendental meditation —

increased creativity and long life — should not be given to a dangerous

country that is constantly busy destroying the world." After Tony Blair's Labour Party won reelection in May 2005, the Maharishi withdrew all instruction in Transcendental Meditation in the UK. The ban was lifted about the same time that Tony Blair left office as Prime Minister.

In 2006, The Columbian newspaper reported that according to the TM movement 6 million people had learned the technique worldwide. In 2007 and 2008, the government of Kyrgyzstan announced a crackdown on illegal religious groups operating in the country, including the "Maharishi cult".

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi died on 5 February 2008 and the leadership of the global Transcendental Meditation movement passed to Maharaja Adhiraj Rajaraam, who is also head of the Global Country of World Peace.

In July 2008, Brahmachari Girish Varma, a nephew of the

Maharishi, announced the formation of the Maharishi World Peace Movement

in Jabalpur

to accomplish the Maharishi's plan for India and to achieve world

peace. Varma serves as chairman. The movement's principles include

practicing the Maharishi's Vedic Health Rituals, daily practice of yoga,

and the construction of Vastu-style homes. Varma also announced the creation of a media news source and portal.

The New York Times

reported in 2011 that according to the "national Transcendental

Meditation program" enrollment had tripled over the last prior three

years. The organization attributes the increased enrollment to reduced

course fees and recent research studies. The Hindu reported in 2011 that "nearly 10 million practitioners in 50 countries" had learned the technique.

Characterizations

Public presentation

Sociologist Roy Wallis

wrote about the three stages of the development of TM through 1977, as

identified by Eric Woodrum. The "Spiritual-Mystical Period", from 1959

to 1965, identified Transcendental Meditation as the primary component

of a holistic approach to spiritual evolution. The "Voguish,

Self-Sufficiency Period", from 1966 to 1969, saw a rapid expansion

through identification with "aspects of the counter-culture" as the

organization simultaneously adapted to its changing image. The

"Secularized, Popular Religious Phase", from 1970 through 1977, when the

movement identified the "practical physiological, material and social

benefits" of TM to mainstream people with virtually no references to

non-worldly topics. Wallis writes that according to a former follower,

TM had dropped its "distinctly religious rhetoric" over time "except for

an inner core of followers" until the late 1970s when TM developed the

TM-Sidhi program to develop "occult powers".

According to sociology of religion scholar, Lorne L. Dawason, the

change from religious terms in the 1950s to an emphasis on scientific

verification in the 1970s was to improve public relations and bring the TM technique into American public schools. In Gurus in America,

Cynthia Humes characterizes the TM movement as meandering from

"plastic export Hinduism" to a non-devotional meditation method marketed

as a "scientific technique" and then back to a "multinational,

capitalist, Vedantic Export Religion", zig-zagging back and forth,

depending on the receptivity of the target audience.

Origins

Author

Peter Russell states that the Maharishi believed the knowledge of the

Vedas had been lost and found many times and its recurrence is outlined

in the Bhagavad-Gita and the teachings of Buddha and Shankara.

Bromley writes that "TM incorporates the teachings of Krishna, the

Buddha, and Shankara" and that the Maharishi says he has "rediscovered a

lost form of meditation that traces back to the Yoga Sutras of

Patanjali.

Alternative medicine author Vimal Patel writes that the Maharishi derived TM from Patanjali's Yoga. Chryssides writes that the Maharishi and his teacher, Brahmananda Saraswati, were from the Shankara tradition of Advaita Vedanta and that the TM-Sidhi program is "based on Patanjali's Yoga Sutras".

According to religious scholar and evangelist Kenneth Boa's book, Cults, World Religions and the Occult, the view that the Transcendental Meditation technique is rooted in the "Vedantic Hinduism" is "repeatedly confirmed" by the Maharishi's writings including Science of Being and the Art of Living and his Commentary on the Bhagavad Gita.

Boa writes that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi "makes it clear" that

Transcendental Meditation was delivered to man about 5,000 years ago by

the Hindu god Krishna, then repeatedly lost and restored by Buddha, Adi Shankara and Brahmananda Saraswati. Religious studies author Carl Olson writes that the Maharishi himself "discovered" Transcendental Meditation.

According to religious scholar Cynthia Humes, Maharishi said TM "was

his own guru's meditation practice" and that he was preserving teachings

"enlivened by his master Brahmananda Saraswati" (Guru Dev). Another scholar says that the TM technique was derived from an old Hindu technique.

Author Patricia Drake writes that "when Guru Dev was about to die he

charged Maharishi with teaching laymen, including the Western World, a

simple means to meditate".

Author John White says "Guru Dev taught Maharishi both the technique

and the philosophy that have resulted in the current phenomenon called

transcendental meditation". [sic]