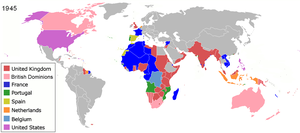

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs. Colonialism in the modern sense began with the "Age of Discovery", led by Portuguese, and then by the Spanish exploration of the Americas, the coasts of Africa, Southwest Asia which is also known as the Middle East, India, and East Asia. The Portuguese and Spanish empires were the first global empires because they were the first to stretch across different continents, covering vast territories around the globe. Between 1580 and 1640, the two empires were both ruled by the Spanish monarchs in personal union. During the late 16th and 17th centuries, England, France and the Dutch Republic also established their own overseas empires, in direct competition with one another.

The end of the 18th and mid 19th century saw the first era of decolonization, when most of the European colonies in the Americas, notably those of Spain, New France and the 13 colonies, gained their independence from their metropole. The Kingdom of Great Britain (uniting Scotland and England), France, Portugal, and the Dutch turned their attention to the Old World, particularly South Africa, India and South East Asia, where coastal enclaves had already been established. The second industrial revolution, in the 19th century, led to what has been termed the era of New Imperialism, when the pace of colonization rapidly accelerated, the height of which was the Scramble for Africa, in which Belgium, Germany and Italy were also participants.

There were deadly battles between colonizing states and revolutions from colonized areas shaping areas of control and establishing independent nations. During the 20th century, the colonies of the defeated central powers in World War I were distributed amongst the victors as mandates, but it was not until the end of World War II that the second phase of decolonization began in earnest.

Periodisation

Some commentators identify three waves of European colonialism.

The three main countries in the first wave of European colonialism were Portugal, Spain and the early Ottoman Empire. The Portuguese started the long age of European colonisation with the conquest of Ceuta, Morocco in 1415, and the conquest and discovery of other African territories and islands, this would also start the movement known as the Age of Discoveries. The Ottomans conquered South Eastern Europe, the Middle East and much of Northern and Eastern Africa between 1359 and 1653 - with the latter territories subjected to colonial occupation, rather than traditional territorial conquest. The Spanish and Portuguese launched the colonisation of the Americas, basing their territorial claims on the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494. This treaty demarcated the respective spheres of influence of Spain and Portugal.

The expansion achieved by Spain and Portugal caught the attention of Britain, France and the Netherlands. The entrance of these three powers into the Caribbean and North America perpetuated European colonialism in these regions.

The second wave of European colonialism commenced with Britain's involvement in Asia in support of the British East India Company; other countries such as France, Portugal and the Netherlands also had involvement in European expansion in Asia.

The third wave ("New Imperialism") consisted of the Scramble for Africa regulated by the terms of the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. The conference effectively divided Africa among the European powers. Vast regions of Africa came under the sway of Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Italy and Spain.

Gilmartin argues that these three waves of colonialism were linked to capitalism. The first wave of European expansion involved exploring the world to find new revenue and perpetuating European feudalism. The second wave focused on developing the mercantile capitalism system and the manufacturing industry in Europe. The last wave of European colonialism solidified all capitalistic endeavours by providing new markets and raw materials.

As a result of these waves of European colonial expansion, only following thirteen present-day independent countries escaped formal colonization by European powers: Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, Iran, Japan, Liberia, Mongolia, Nepal, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Thailand and Turkey as well as North Yemen, the former independent country which is now part of Yemen.

Imperial Russia

The Territorial changes of Russia happened by means of military conquest and by ideological and political unions over the centuries. This section covers (1533–1914).

Ivan III (reigned 1462–1505) and Vasili III (reigned 1505–1533) had already expanded Muscovy's (1283–1547) borders considerably by annexing the Novgorod Republic (1478), the Grand Duchy of Tver in 1485, the Pskov Republic in 1510, the Appanage of Volokolamsk in 1513, and the principalities of Ryazan in 1521 and Novgorod-Seversky in 1522.

After a period of political instability, 1598 to 1613 the Romanovs came to power (1613) and the expansion-colonization process of the Tsardom continued. While western Europe colonized the New World, Russia expanded overland - to the east, north and south. This continued for centuries; by the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire reached from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, and for some time included colonies in the Alaska (1732-1867) and a short-lived unofficial colony in Africa (1889) in present-day Djibouti. The acquisition of new territories, especially in the Caucasus, had an invigorating effect on the rest of Russia. According to two Russian historians:

- the culture of Russia and that of the Caucasian peoples interacted in a reciprocally beneficial manner. The turbulent tenor of life in the Caucasus, the mountain peoples' love of freedom, and their willingness to die for independence were felt far beyond the local interaction of the Caucasian peoples and coresident Russians: they injected a potent new spirit into the thinking and creative work of Russia's progressives, strengthened the liberationist aspirations of Russian writers and exiled Decembrists, and influenced distinguished Russian democrats, poets, and prose writers, including Alexander Griboyedov, Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, and Leo Tolstoy. These writers, who generally supported the Caucasian fight for liberation, went beyond the chauvinism of the colonial autocracy and rendered the Caucasian peoples' cultures accessible to the Russian intelligentsia. At the same time, Russian culture exerted an influence on Caucasian cultures, bolstering positive aspects while weakening the impact of the Caucasian peoples' reactionary feudalism and reducing the internecine fighting between tribes and clans.

Expansion into Asia

The first stage to 1650 was an expansion eastward from the Urals to the Pacific. Geographical expeditions mapped much of Siberia. The second stage from 1785 to 1830 looked south to the areas between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The key areas were Armenia and Georgia, with some better penetration of the Ottoman Empire, and Persia. By 1829, Russia controlled all of the Caucasus as shown in the Treaty of Adrianople of 1829. The third era, 1850 to 1860, was a brief interlude jumping to the East Coast, annexing the region from the Amur River to Manchuria. The fourth era, 1865 to 1885 incorporated Turkestan, and the northern approaches to India, sparking British fears of a threat to India in The Great Game.

Portuguese and Spanish exploration and colonization

European colonization of both Eastern and Western Hemispheres has its roots in Portuguese exploration. There were financial and religious motives behind this exploration. By finding the source of the lucrative spice trade, the Portuguese could reap its profits for themselves. They would also be able to probe the existence of the fabled Christian kingdom of Prester John, with an eye to encircling the Islamic Ottoman Empire, itself gaining territories and colonies in Eastern Europe. The first foothold outside of Europe was gained with the conquest of Ceuta in 1415. During the 15th century, Portuguese sailors discovered the Atlantic islands of Madeira, Azores, and Cape Verde, which were duly populated, and pressed progressively further along the west African coast until Bartolomeu Dias demonstrated it was possible to sail around Africa by rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, paving the way for Vasco da Gama to reach India in 1498.

Portuguese successes led to Spanish financing of a mission by Christopher Columbus in 1492 to explore an alternative route to Asia, by sailing west. When Columbus eventually made landfall in the Caribbean Antilles he believed he had reached the coast of India, and that the people he encountered there were Indians with red skin. This is why Native Americans have been called Indians or red-Indians. In truth, Columbus had arrived on a continent that was new to the Europeans, the Americas. After Columbus' first trips, competing Spanish and Portuguese claims to new territories and sea routes were solved with the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which divided the world outside of Europe in two areas of trade and exploration, between the Iberian kingdoms of Castile and Portugal along a north–south meridian, 370 leagues west of Cape Verde. According to this international agreement, the larger part of the Americas and the Pacific Ocean were open to Spanish exploration and colonization, while Africa, the Indian Ocean and most of Asia were assigned to Portugal.

The boundaries specified by the Treaty of Tordesillas were put to the test in 1521 when Ferdinand Magellan and his Spanish sailors (among other Europeans), sailing for the Spanish Crown became the first European to cross the Pacific Ocean, reaching Guam and the Philippines, parts of which the Portuguese had already explored, sailing from the Indian Ocean. The two by now global empires, which had set out from opposing directions, had finally met on the other side of the world. The conflicts that arose between both powers were finally solved with the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, which defined the areas of Spanish and Portuguese influence in Asia, establishing the anti meridian, or line of demarcation on the other side of the world.

During the 16th century the Portuguese continued to press both eastwards and westwards into the Oceans. Towards Asia they made the first direct contact between Europeans and the peoples inhabiting present day countries such as Mozambique, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, East Timor (1512), China, and finally Japan. In the opposite direction, the Portuguese colonized the huge territory that eventually became Brasil, and the Spanish conquistadores established the vast Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru, and later of Río de la Plata (Argentina) and New Granada (Colombia). In Asia, the Portuguese encountered ancient and well populated societies, and established a seaborne empire consisting of armed coastal trading posts along their trade routes (such as Goa, Malacca and Macau), so they had relatively little cultural impact on the societies they engaged. In the Western Hemisphere, the European colonization involved the emigration of large numbers of settlers, soldiers and administrators intent on owning land and exploiting the apparently primitive (as perceived by Old World standards) indigenous peoples of the Americas. The result was that the colonization of the New World was catastrophic: native peoples were no match for European technology, ruthlessness, or their diseases which decimated the indigenous population.

Spanish treatment of the indigenous populations caused a fierce debate, the Valladolid Controversy, over whether Indians possessed souls and if so, whether they were entitled to the basic rights of mankind. Bartolomé de Las Casas, author of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, championed the cause of the native peoples, and was opposed by Sepúlveda, who claimed Amerindians were "natural slaves".

The Roman Catholic Church played a large role in Spanish and Portuguese overseas activities. The Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans, notably Francis Xavier in Asia and Junípero Serra in North America, were particularly active in this endeavour. Many buildings erected by the Jesuits still stand, such as the Cathedral of Saint Paul in Macau and the Santisima Trinidad de Paraná in Paraguay, the latter an example of the Jesuit Reductions. The Dominican and Franciscan buildings of California's missions and New Mexico's missions stand restored, such as Mission Santa Barbara in Santa Barbara, California and San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

As characteristically happens in any colonialism, European or not, previous or subsequent, both Spain and Portugal profited handsomely from their newfound overseas colonies: the Spanish from gold and silver from mines such as Potosí and Zacatecas in New Spain, the Portuguese from the huge markups they enjoyed as trade intermediaries, particarlarly during the Nanban Japan trade period. The influx of precious metals to the Spanish monarchy's coffers allowed it to finance costly religious wars in Europe which ultimately proved its economic undoing: the supply of metals was not infinite and the large inflow caused inflation and debt, and subsequently affected the rest of Europe.

Northern European challenges to the Iberian hegemony

It was not long before the exclusivity of Iberian claims to the Americas was challenged by other up and coming European powers, primarily the Netherlands, France and England: the view taken by the rulers of these nations is epitomized by the quotation attributed to Francis I of France demanding to be shown the clause in Adam's will excluding his authority from the New World. This challenge initially took the form of piratical attacks (such as those by Francis Drake) on Spanish treasure fleets or coastal settlements. Later the Northern European countries began establishing settlements of their own, primarily in areas that were outside of Spanish interests, such as what is now the eastern seaboard of the United States and Canada, or islands in the Caribbean, such as Aruba, Martinique and Barbados, that had been abandoned by the Spanish in favour of the mainland and larger islands.

Whereas Spanish colonialism was based on the religious conversion and exploitation of local populations via encomiendas (many Spaniards emigrated to the Americas to elevate their social status, and were not interested in manual labour), Northern European colonialism was bolstered by those emigrating for religious reasons (for example, the Mayflower voyage). The motive for emigration was not to become an aristocrat or to spread one's faith but to start a new society afresh, structured according to the colonists wishes. The most populous emigration of the 17th century was that of the English, who after a series of wars with the Dutch and French came to dominate the Thirteen Colonies on the eastern coast of the present day United States and other colonies such as Newfoundland and Rupert's Land in what is now Canada.

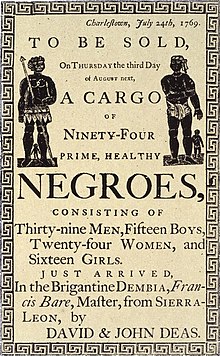

However, the English, French and Dutch were no more averse to making a profit than the Spanish and Portuguese, and whilst their areas of settlement in the Americas proved to be devoid of the precious metals found by the Spanish, trade in other commodities and products that could be sold at massive profit in Europe provided another reason for crossing the Atlantic, in particular furs from Canada, tobacco and cotton grown in Virginia and sugar in the islands of the Caribbean and Brazil. Due to the massive depletion of indigenous labour, plantation owners had to look elsewhere for manpower for these labour-intensive crops. They turned to the centuries-old slave trade of west Africa and began transporting Africans across the Atlantic on a massive scale – historians estimate that the Atlantic slave trade brought between 10 and 12 million black African slaves to the New World. The islands of the Caribbean soon came to be populated by slaves of African descent, ruled over by a white minority of plantation owners interested in making a fortune and then returning to their home country to spend it.

Role of companies in early colonialism

From its very outset, Western colonialism was operated as a joint public-private venture. Columbus' voyages to the Americas were partially funded by Italian investors, but whereas the Spanish state maintained a tight rein on trade with its colonies (by law, the colonies could only trade with one designated port in the mother country and treasure was brought back in special convoys), the English, French and Dutch granted what were effectively trade monopolies to joint-stock companies such as the East India Companies and the Hudson's Bay Company.

Imperial Russia had no state sponsored expeditions or colonization in the Americas, but did charter the first Russian joint-stock commercial enterprise, the Russian America Company, which did sponsor those activities in its territories.

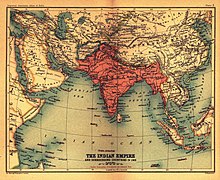

European colonies in India

In May 1498, the Portuguese set foot in Kozhikode in Kerala, making them the first Europeans to sail to India. Rivalry among reigning European powers saw the entry of the Dutch, English, French, Danish and others. The kingdoms of India were gradually taken over by the Europeans and indirectly controlled by puppet rulers. In 1600, Queen Elizabeth I accorded a charter, forming the East India Company to trade with India and eastern Asia. The English landed in India in Surat in 1612. By the 19th century, they had assumed direct and indirect control over most of India.

Independence in the Americas (1770–1820)

During the five decades following 1770, Britain, France, Spain and Portugal lost many of their possessions in the Americas.

Britain and the Thirteen Colonies

After the conclusion of the Seven Years' War in 1763, Britain had emerged as the world's dominant power, but found itself mired in debt and struggling to finance the Navy and Army necessary to maintain a global empire. The British Parliament's attempt to raise taxes from North American colonists raised fears among the Americans that their rights as "Englishmen", and particularly their rights of self-government, were in danger.

From 1765, a series of disputes with Parliament over taxation led to the American Revolution, first to informal committees of correspondence among the colonies, then to coordinated protest and resistance, with an important event in 1770, the Boston Massacre. A standing army was formed by the United Colonies, and independence was declared by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776. A new nation was born, the United States of America, and all royal officials were expelled. On their own the Patriots captured a British Invasion army and France recognized the new nation, formed military alliance, declared war on Britain, and left the superpower without any major ally. The American War of Independence continued until 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was signed. Britain recognised the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded by the British possessions to the North, Florida to the South, and the Mississippi River to the west.

France and the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804)

The Haitian Revolution, a slave revolt led by Toussaint L'Ouverture in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, established Haïti as a free, black republic, the first of its kind. Haiti became the second independent nation that was a former European colony in the Western Hemisphere after the United States. Africans and people of African ancestry freed themselves from slavery and colonization by taking advantage of the conflict among whites over how to implement the reforms of the French Revolution in this slave society. Although independence was declared in 1804, it was not until 1825 that it was formally recognized by King Charles X of France.

Spain and the Wars of Independence in Latin America

The gradual decline of Spain as an imperial power throughout the 17th century was hastened by the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), as a result of which it lost its European imperial possessions. The death knell for the Spanish Empire in the Americas was Napoleon's invasion of the Iberian peninsula in 1808. With the installation of his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne, the main tie between the metropole and its colonies in the Americas, the Spanish monarchy, had been cut, leading the colonists to question their continued subordination to a declining and distant country. With an eye on the events of the American Revolution forty years earlier, revolutionary leaders began bloody wars of independence against Spain, whose armies were ultimately unable to maintain control. By 1831, Spain had been ejected from the mainland of the Americas, leaving a collection of independent republics that stretched from Chile and Argentina in the south to Mexico in the north. Spain's colonial possessions were reduced to Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and a number of small islands in the Pacific, all of which she was to lose to the United States in the 1898 Spanish–American War or sell to Germany shortly thereafter.

Portugal and Brazil

Brazil was the only country in Latin America to gain its independence without bloodshed. The invasion of Portugal by Napoleon in 1808 had forced King João VI to escape to Brazil and establish his court in Rio de Janeiro. For thirteen years, Portugal was ruled from Brazil (the only instance of such a reversal of roles between colony and metropole) until his return to Portugal in 1821. His son, Dom Pedro, was left in charge of Brazil and in 1822 he declared independence from Portugal and himself the Emperor of Brazil. Unlike Spain's former colonies which had abandoned the monarchy in favour of republicanism, Brazil therefore retained its links with its monarchy, the House of Braganza.

India (1858 onwards)

Vasco da Gama's maritime success to discover for Europeans a new sea route to India in 1498 paved the way for direct Indo-European commerce. The Portuguese soon set up trading-posts in Goa, Daman, Diu and Bombay. The next to arrive were the Dutch, the English—who set up a trading-post in the west-coast port of Surat in 1619—and the French. The internal conflicts among Indian Kingdoms gave opportunities to the European traders to gradually establish political influence and appropriate lands. Although these continental European powers were to control various regions of southern and eastern India during the ensuing century, they would eventually lose all their territories in India to the British, with the exception of the French outposts of Pondicherry and Chandernagore, the Dutch port in Travancore, and the Portuguese colonies of Goa, Daman, and Diu.

The British in India

The English East India Company had been given permission by the Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1617 to trade in India. Gradually the company's increasing influence led the de jure Mughal emperor Farrukh Siyar to grant them dastaks or permits for duty-free trade in Bengal in 1717. The Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah, the de facto ruler of the Bengal province, opposed British attempts to use these permits. This led to the Battle of Plassey in 1757, in which the armies of the East India Company, led by Robert Clive, defeated the Nawab's forces. This was the first political foothold with territorial implications that the British had acquired in India. Clive was appointed by the company as its first Governor of Bengal in 1757. This was combined with British victories over the French at Madras, Wandiwash and Pondicherry that, along with wider British successes during the Seven Years' War, reduced French influence in India. After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the company acquired the civil rights of administration in Bengal from the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II; it marked the beginning of its formal rule, which was to engulf eventually most of India and extinguish the Moghul rule and dynasty itself in less than a century. The East India Company monopolized the trade of Bengal. They introduced a land taxation system called the Permanent Settlement which introduced a feudal-like structure (See Zamindar) in Bengal. By the 1850s, the East India Company controlled most of the Indian sub-continent, which included present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. Their policy was sometimes summed up as Divide and Rule, taking advantage of the enmity festering between various princely states and social and religious groups.

The first major movement against the British Company's high handed rule resulted in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, also known as the "Indian Mutiny" or "Sepoy Mutiny" or the "First War of Independence". After a year of turmoil, and reinforcement of the East India Company's troops with British soldiers, the Company overcame the rebellion. The nominal leader of the uprising, the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, was exiled to Burma, his children were beheaded and the Moghul line abolished. In the aftermath all power was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown, which began to administer most of India as a colony; the company's lands were controlled directly and the rest through the rulers of what it called the Princely states. There were 565 princely states when the Indian subcontinent gained independence from Britain in August 1947.

During period of the British Raj, famines in India, often attributed to El Nino droughts and failed government policies, were some of the worst ever recorded, including the Great Famine of 1876–78, in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died and the Indian famine of 1899–1900, in which 1.25 to 10 million people died. The Third Plague Pandemic started in China in the middle of the 19th century, spreading plague to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone. Despite persistent diseases and famines, however, the population of the Indian subcontinent, which stood at about 125 million in 1750, had reached 389 million by 1941.

Other European Empires in India

Like the other European colonists, the French began their colonisation via commercial activities, starting with the establishment of a factory in Surat in 1668. The French started to settle down in India in 1673, beginning with the purchase of land at Chandernagore from the Mughal Governor of Bengal, followed by the acquisition of Pondicherry from the Sultan of Bijapur the next year. Both became the centres of the maritime commercial activities that the French conducted in India. The French also had trading posts in Mahe, Karikal and Yanaom. Similar to the situation in Tahiti and Martinique, the French colonial administrative area was insular, but, in India, the French authority was isolated on the peripheries of a British-dominated territory.

By the early eighteenth century, the French had become the chief European rivals of the British. During the eighteenth century, it was highly possible for the Indian subcontinent to have succumbed to French control, but the defeat inflicted on them in the Seven Years War (1756–1763) permanently curtailed French ambitions. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 restored the original five to the French while making it clear that France could not expand its control beyond these areas.

The beginning of the Portuguese occupation of India can be traced back to the arrival of Vasco da Gama near Calicut on 20 May 1498. Soon after this, other explorers, traders and missionaries followed. By 1515, the Portuguese were the strongest naval power in the Indian Ocean and the Malabar Coast was dominated by them.

New Imperialism (1870–1914)

The policy and ideology of European colonial expansion between the 1870s (circa opening of Suez Canal and Second Industrial Revolution) and the outbreak of World War I in 1914 are often characterised as the "New Imperialism." The period is distinguished by an unprecedented pursuit of what has been termed "empire for empire's sake," aggressive competition for overseas territorial acquisitions and the emergence in colonising countries of doctrines of racial superiority which denied the fitness of subjugated peoples for self-government.

During this period, Europe's powers added nearly 8,880,000 square miles (23,000,000 km2) to their overseas colonial possessions. As it was mostly unoccupied by the Western powers as late as the 1880s, Africa became the primary target of the "new" imperialist expansion (known as the Scramble for Africa), although conquest took place also in other areas — notably south-east Asia and the East Asian seaboard, where Japan joined the European powers' scramble for territory.

The Berlin Conference (1884–1885) mediated the imperial competition among Britain, France and Germany, defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of colonial claims and codifying the imposition of direct rule, accomplished usually through armed force.

In Germany, rising pan-Germanism was coupled to imperialism in the Alldeutsche Verband ("Pangermanic League"), which argued that Britain's world power position gave the British unfair advantages on international markets, thus limiting Germany's economic growth and threatening its security.

Asking whether colonies paid, economic historian Grover Clark argues an emphatic "No!" He reports that in every case the support cost, especially the military system necessary to support and defend the colonies outran the total trade they produced. Apart from the British Empire, they were not favored destinations for the immigration of surplus populations.

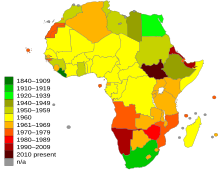

The scramble for Africa

Africa was the target of the third wave of European colonialism, after that of the Americas and Asia. Many European statesmen and industrialists wanted to accelerate the Scramble for Africa, securing colonies before they strictly needed them. As a champion of Realpolitik, Bismarck disliked colonies and thought they were a waste of time, but his hand was forced by pressure from both the elites and the general population which considered the colonization a necessity for German prestige. German colonies in Togoland, Samoa, South-West Africa and New Guinea had corporate commercial roots, while the equivalent German-dominated areas in East Africa and China owed more to political motives. The British also took an interest in Africa, using the East Africa Company to take over what are now Kenya and Uganda. The British crown formally took over in 1895 and renamed the area the East Africa Protectorate.

Leopold II of Belgium personally owned the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908, When round after round of international scandal regarding the abusive treatment of native workers forced the Belgium government to take full ownership and responsibility. The Dutch Empire continued to hold the Dutch East Indies, which was one of the few profitable overseas colonies.

In the same manner, Italy tried to conquer its "place in the sun," acquiring Somaliland in 1899–90, Eritrea and 1899, and, taking advantage of the "Sick man of Europe," the Ottoman Empire, also conquered Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern Libya) with the 1911 Treaty of Lausanne. The conquest of Ethiopia, which had remained the last African independent territory, had to wait till the Second Italo-Abyssinian War in 1935–36 (the First Italo-Ethiopian War in 1895–96 had ended in defeat for Italy).

The Portuguese and Spanish colonial empire were smaller, mostly legacies of past colonization. Most of their colonies had acquired independence during the Latin American revolutions at the beginning of the 19th century.

Imperialism in Asia

In Asia, The Great Game, which lasted from 1813 to 1907, opposed the British Empire against Imperial Russia for supremacy in central Asia. China was opened to Western influence starting with the First and Second Opium Wars (1839–1842; 1856–1860). After the visits of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1852–1854, Japan opened itself to the Western world during the Meiji period (1868–1912).

Imperialism also took place in Burma, Indonesia (Netherlands East Indies), Malaya and the Philippines. Burma had been under British rule for nearly a hundred years, however, it was always considered an “imperial backwater”. This accounts for the fact that Burma does not have an obvious colonial legacy and is not a part of the Commonwealth. In the beginning, in the mid-1820s, Burma was administered from Penang in Britain's Straits Settlements. However, it was soon brought within British India, of which it remained a part until 1937. Burma was governed as a province of India, not considered very important, and barely any accommodation was made to Burmese political culture or sensitivities. As reforms began to move India towards independence, Burma was simply dragged along.

Inter-War Period (1918–1939)

The colonial map was redrawn following the defeat of the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire after the World War I (1914–18). Colonies from the defeated empires were transferred to the newly founded League of Nations, which itself redistributed it to the victorious powers as "mandates". The secret 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement partitioned the Middle East between Britain and France. French mandates included Syria and Lebanon, whilst the British were granted Iraq and Palestine. The bulk of the Arabian peninsula became the independent Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1922. The discovery of the world's largest easily accessible crude oil deposits led to an influx of Western oil companies that dominated the region's economies until the 1970s, and making the emirs of the oil states immensely rich, enabling them to consolidate their hold on power and giving them a stake in preserving Western hegemony over the region. During the 1920 and 1930s Iraq, Syria and Egypt moved towards independence, although the British and French did not formally depart the region until they were forced to do so after World War II.

Japanese imperialism

For Japan, the second half of the nineteenth century was a period of internal turmoil succeeded by a period of rapid development. After being closed for centuries to Western influence, Japan was forced by the United States to open itself to the West during the Meiji Era (1868–1912), characterized by swift modernization and borrowings from European culture (in law, science, etc.) This, in turn, helped make Japan the modern power that it is now, which was symbolized as soon as the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War: this war marked the first victory of an Asian power against a European imperial power, and led to widespread fears among European populations. During the first part of the 20th century, while China was still subject to various European imperialisms, Japan became an imperialist power, conquering what it called a "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".

With the final revision of treaties in 1894, Japan may be considered to have joined the family of nations on a basis of equality with the western states. From this same time imperialism became a dominant motive in Japanese policy.

Japan ruled over and governed Korea and Taiwan from 1895 when the Treaty of Shimonoseki was concluded to 1945 when Japan was defeated. In 1910, Korea was formally annexed to the Japanese Empire. According to the Korean, The Japanese colonization of Korea was particularly brutal, even by 20th-century standards. This brutal colonization included the use of Korean "comfort women" who were forced to serve as sex slaves in Japanese Army brothels.

In 1931 Japanese army units based in Manchuria seized control of the region and created the puppet state of Manchukuo. Full-scale war with China followed in 1937, drawing Japan toward an overambitious bid for Asian hegemony (Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere), which ultimately led to defeat and the loss of all its overseas territories after World War II (see Japanese expansionism and Japanese nationalism). As in Korea, the Japanese treatment of the Chinese people was particularly brutal as exemplified by the Nanjing Massacre.

Second Decolonization (1945–99)

Anticolonialist movements had begun to gain momentum after the close of World War I, which had seen colonial troops fight alongside those of the metropole, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's speech on the Fourteen Points. However, it was not until the end of World War II that they were fully mobilised. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 Atlantic Charter declared that the signatories would "respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live". Though Churchill subsequently claimed this applied only to those countries under Nazi occupation, rather than the British Empire, the words were not so easily retracted: for example, the legislative assembly of Britain's most important colony, India, passed a resolution stating that the Charter should apply to it too.

In 1945, the United Nations (UN) was founded when 50 nations signed the UN Charter, which included a statement of its basis in the respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples. In 1952, demographer Alfred Sauvy coined the term "Third World" in reference to the French Third Estate. The expression distinguished nations that aligned themselves with neither the West nor the Soviet Bloc during the Cold War. In the following decades, decolonization would strengthen this group which began to be represented at the United Nations. The Third World's first international move was the 1955 Bandung Conference, led by Jawaharlal Nehru for India, Gamal Abdel Nasser for Egypt and Josip Broz Tito for Yugoslavia. The Conference, which gathered 29 countries representing over half the world's population, led to the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961.

Although the U.S. had first opposed itself to colonial empires, the Cold War concerns about Soviet influence in the Third World caused it to downplay its advocacy of popular sovereignty and decolonization. France thus received financial support in the First Indochina War (1946–54) and the U.S. did not interfere in the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62). Decolonization itself was a seemingly unstoppable process. In 1960, after a number countries gained independence, the UN had reached 99 members states: the decolonization of Africa was almost complete. In 1980, the UN had 154 member states, and in 1990, after Namibia's independence, 159 states. Hong Kong and Macau transferred sovereignty to China in 1997 and 1999 finally marked the end of European colonial era.

Role of Soviet Union and China

The Soviet Union was a main supporter of decolonization movements and communist parties across the world that denounced imperialism and colonization. While the Non-Aligned Movement, created in 1961 following the Bandung 1955 Conference, was supposedly neutral, the "Third World" being opposed to both the "First" and the "Second" Worlds, geopolitical concerns, as well as the refusal of the U.S. to support decolonization movements against its NATO European allies, led the national liberation movements to look increasingly toward the East. However, China's appearance on the world scene, under the leadership of Mao Zedong, created a rupture between the Soviet and Chinese factions in Communist parties around the world, all of which opposed imperialism. Cuba, with Soviet financing, send combat troops to help left-wing independence movements in Angola and Mozambique.

Globally, the non-aligned movement, led by Jawaharlal Nehru (India), Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia) and Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt) tried to create a block of nations powerful enough to be dependent on neither the United States nor the Soviet Union, but finally tilted towards the Soviet Union, while smaller independence movements, both by strategic necessity and ideological choice, were supported either by Moscow or by Beijing. Few independence movements were totally independent from foreign aid. In 1960s and 1970s, Leonid Brezhnev and Mao Zedong gave influential support to those newly African governments which many became one-party socialist states.

Postcolonialism

Postcolonialism is a term used to recognise the continued and troubling presence and influence of colonialism within the period we designate as after-the-colonial. It refers to the ongoing effects that colonial encounters, dispossession and power have in shaping the familiar structures (social, political, spatial, uneven global interdependencies) of the present world. Postcolonialism, in itself, questions the end of colonialism.