The interplanetary dust cloud, or zodiacal cloud (as the source of the zodiacal light), consists of cosmic dust (small particles floating in outer space) that pervades the space between planets within planetary systems, such as the Solar System. This system of particles has been studied for many years in order to understand its nature, origin, and relationship to larger bodies. There are several methods to obtain space dust measurement.

In the Solar System, interplanetary dust particles have a role in scattering sunlight and in emitting thermal radiation, which is the most prominent feature of the night sky's radiation, with wavelengths ranging 5–50 μm. The particle sizes of grains characterizing the infrared emission near Earth's orbit typically range 10–100 μm. Microscopic impact craters on lunar rocks returned by the Apollo Program revealed the size distribution of cosmic dust particles bombarding the lunar surface. The ’’Grün’’ distribution of interplanetary dust at 1 AU, describes the flux of cosmic dust from nm to mm sizes at 1 AU.

The total mass of the interplanetary dust cloud is approximately 3.5×1016 kg, or the mass of an asteroid of radius 15 km (with density of about 2.5 g/cm3). Straddling the zodiac along the ecliptic, this dust cloud is visible as the zodiacal light in a moonless and naturally dark sky and is best seen sunward during astronomical twilight.

The Pioneer spacecraft observations in the 1970s linked the zodiacal light with the interplanetary dust cloud in the Solar System. Also, the VBSDC instrument on the New Horizons probe was designed to detect impacts of the dust from the zodiacal cloud in the Solar System.

Origin

The sources of interplanetary dust particles (IDPs) include at least: asteroid collisions, cometary activity and collisions in the inner Solar System, Kuiper belt collisions, and interstellar medium grains (Backman, D., 1997). The origins of the zodiacal cloud have long been subject to one of the most heated controversies in the field of astronomy.

It was believed that IDPs had originated from comets or asteroids whose particles had dispersed throughout the extent of the cloud. However, further observations have suggested that Mars dust storms may be responsible for the zodiacal cloud's formation.

Life cycle of a particle

The main physical processes "affecting" (destruction or expulsion mechanisms) interplanetary dust particles are: expulsion by radiation pressure, inward Poynting-Robertson (PR) radiation drag, solar wind pressure (with significant electromagnetic effects), sublimation, mutual collisions, and the dynamical effects of planets (Backman, D., 1997).

The lifetimes of these dust particles are very short compared to the lifetime of the Solar System. If one finds grains around a star that is older than about 10,000,000 years, then the grains must have been from recently released fragments of larger objects, i.e. they cannot be leftover grains from the protoplanetary disk (Backman, private communication). Therefore, the grains would be "later-generation" dust. The zodiacal dust in the Solar System is 99.9% later-generation dust and 0.1% intruding interstellar medium dust. All primordial grains from the Solar System's formation were removed long ago.

Particles which are affected primarily by radiation pressure are known as "beta meteoroids". They are generally less than 1.4 × 10−12 g and are pushed outward from the Sun into interstellar space.

Cloud structures

The interplanetary dust cloud has a complex structure (Reach, W., 1997). Apart from a background density, this includes:

- At least 8 dust trails—their source is thought to be short-period comets.

- A number of dust bands, the sources of which are thought to be asteroid families in the main asteroid belt. The three strongest bands arise from the Themis family, the Koronis family, and the Eos family. Other source families include the Maria, Eunomia, and possibly the Vesta and/or Hygiea families (Reach et al. 1996).

- At least 2 resonant dust rings are known (for example, the Earth-resonant dust ring, although every planet in the Solar System is thought to have a resonant ring with a "wake") (Jackson and Zook, 1988, 1992) (Dermott, S.F. et al., 1994, 1997)

Rings of dust

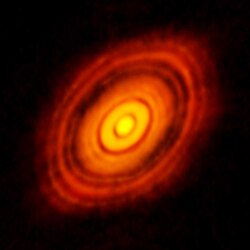

Interplanetary dust has been found to form rings of dust in the orbital space of Mercury and Venus. Venus's orbital dust ring is suspected to originate either from yet undetected Venus trailing asteroids, interplanetary dust migrating in waves from orbital space to orbital space, or from the remains of the Solar System's circumstellar disc, out of which its proto-planetary disc and then itself, the Solar planetary system, formed.

Dust collection on Earth

In 1951, Fred Whipple predicted that micrometeorites smaller than 100 micrometers in diameter might be decelerated on impact with the Earth's upper atmosphere without melting. The modern era of laboratory study of these particles began with the stratospheric collection flights of Donald E. Brownlee and collaborators in the 1970s using balloons and then U-2 aircraft.

Although some of the particles found were similar to the material in present-day meteorite collections, the nanoporous nature and unequilibrated cosmic-average composition of other particles suggested that they began as fine-grained aggregates of nonvolatile building blocks and cometary ice. The interplanetary nature of these particles was later verified by noble gas and solar flare track observations.

In that context a program for atmospheric collection and curation of these particles was developed at Johnson Space Center in Texas. This stratospheric micrometeorite collection, along with presolar grains from meteorites, are unique sources of extraterrestrial material (not to mention being small astronomical objects in their own right) available for study in laboratories today.

Experiments

Spacecraft that have carried dust detectors include Helios, Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Ulysses (heliocentric orbit out to the distance of Jupiter), Galileo (Jupiter Orbiter), Cassini (Saturn orbiter), and New Horizons (see Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter).

Obscuring effect

The Solar interplanetary dust cloud obscures the extragalactic background light, making observations of it from the Inner Solar System very limited.

Major Review Collections

Collections of review articles on various aspects of interplanetary dust and related fields appeared in the following books:

In 1978 Tony McDonnell edited the book Cosmic Dust which contained chapters on comets along with zodiacal light as indicator of interplanetary dust, meteors, interstellar dust, microparticle studies by sampling techniques, and microparticle studies by space instrumentation. Attention is also given to lunar and planetary impact erosion, aspects of particle dynamics, and acceleration techniques and high-velocity impact processes employed for the laboratory simulation of effects produced by micrometeoroids.

2001 Eberhard Grün, Bo Gustafson, Stan Dermott, and Hugo Fechtig published the book Interplanetary Dust. Topics covered are: historical perspectives; cometary dust; near-Earth environment; meteoroids and meteors; properties of interplanetary dust, information from collected samples; in situ measurements of cosmic dust; numerical modeling of the Zodiacal Cloud structure; synthesis of observations; instrumentation; physical processes; optical properties of interplanetary dust; orbital evolution of interplanetary dust; circumplanetary dust, observations and simple physics; interstellar dust and circumstellar dust disks.

2019 Rafael Rodrigo, Jürgen Blum, Hsiang-Wen Hsu, Detlef V. Koschny, Anny-Chantal Levasseur-Regourd, Jesús Martín-Pintado, Veerle J. Sterken, and Andrew Westphal collected reviews in the book Cosmic Dust from the Laboratory to the Stars. Included are discussions of dust in various environments: from planetary atmospheres and airless bodies over interplanetary dust, meteoroids, comet dust and emissions from active moons to interstellar dust and protoplanetary disks. Diverse research techniques and results, including in-situ measurement, remote observation, laboratory experiments and modelling, and analysis of returned samples are discussed.

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {b}}^{\dagger },{\hat {b}}^{\dagger }\right]_{-}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/61181ceded319373055a84dc6a94dc4380a1f656)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {b}},{\hat {b}}\right]_{-}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/63816bf8766923817dc47201e85bbe12285859f6)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {b}},{\hat {b}}^{\dagger }\right]_{-}=1}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/abe1bdcae41e256df878e30bf41844ccae4cca7d)

![{\displaystyle \left[A,B\right]_{-}\equiv AB-BA}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2e1f351b2b50343742d5e576c8c00a03c6ff23cf)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {b}}_{i}^{\dagger },{\hat {b}}_{j}^{\dagger }\right]_{-}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/48d6e2a47dd564adc74c5da6c592f1c4f6f1a101)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {b}}_{i},{\hat {b}}_{j}\right]_{-}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4cad36d9d2b78500fd609df4a74f20c26b35214e)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {b}}_{i},{\hat {b}}_{j}^{\dagger }\right]_{-}=\delta _{ij}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/47d7016b65f60e627505089726148f1c8bf5e597)

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {N}}[f]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0f8aef7c6ef65951ee22fafaac49809eb68b7575)

\\&={\frac {1}{\Gamma (-n)}}\int _{-\infty }^{0}\mathrm {d} x\,e^{x}\,f(x)\,(-x)^{-(n+1)}\\&={\frac {1}{\Gamma (-n)}}{\mathcal {M}}_{-x}[e^{x}f(x)](-n),\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0a0badca6663868b918a3e7ef247be1dda7873b7)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {f}}^{\dagger },{\hat {f}}^{\dagger }\right]_{+}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5d3ac153ef4ac8ff6806b35d5aff966d0f3ed9ad)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {f}},{\hat {f}}\right]_{+}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8cc4e2943986870261f822b8db6088b0fb8f794d)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {f}},{\hat {f}}^{\dagger }\right]_{+}=1}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d4c217f8baf594cc8f6339716924f8efad7ed5db)

![{\displaystyle \left[A,B\right]_{+}\equiv AB+BA}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d8a27bf9e6afd04ecc39ffdbc55913c39169dc41)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {f}}_{i}^{\dagger },{\hat {f}}_{j}^{\dagger }\right]_{+}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e028a2ae7b22555b9cbcd653a6550a7c03708238)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {f}}_{i},{\hat {f}}_{j}\right]_{+}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb699f8f0c45aff921bb302cf002da2487f840e9)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {f}}_{i},{\hat {f}}_{j}^{\dagger }\right]_{+}=\delta _{ij}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/47e336718a18e3acdf8a79afb3538e6e9ab20fd6)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}T\left[\phi (x_{1})\cdots \phi (x_{n})\right]=&:\phi (x_{1})\cdots \phi (x_{n}):+\sum _{\textrm {perm}}\langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{1})\phi (x_{2})\right]|0\rangle :\phi (x_{3})\cdots \phi (x_{n}):\\&+\sum _{\textrm {perm}}\langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{1})\phi (x_{2})\right]|0\rangle \langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{3})\phi (x_{4})\right]|0\rangle :\phi (x_{5})\cdots \phi (x_{n}):\\\vdots \\&+\sum _{\textrm {perm}}\langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{1})\phi (x_{2})\right]|0\rangle \cdots \langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{n-1})\phi (x_{n})\right]|0\rangle \end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/005285fd167f479c8af13e035342003c6d7fd356)

![{\displaystyle \sum _{\text{perm}}\langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{1})\phi (x_{2})\right]|0\rangle \cdots \langle 0|T\left[\phi (x_{n-2})\phi (x_{n-1})\right]|0\rangle \phi (x_{n}).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/58e20da462c8b8c4048918b0cd2fabd360eb9edd)