From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Stroke | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | I61-I64ner |

| ICD-9 | 434.91 |

| OMIM | 601367 |

| DiseasesDB | 2247 |

| MedlinePlus | 000726 |

| eMedicine | neuro/9 emerg/558 emerg/557 pmr/187 |

| Patient UK | Stroke |

| MeSH | D020521 |

A stroke, sometimes referred to as a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), cerebrovascular insult (CVI), or colloquially brain attack is the loss of brain function due to a disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This disturbance is due to either ischemia (lack of blood flow) or hemorrhage.[1] As a result, the affected area of the brain cannot function normally, which might result in an inability to move one or more limbs on one side of the body, failure to understand or formulate speech, or a vision impairment of one side of the visual field.[2]

Ischemia is caused by either blockage of a blood vessel via thrombosis or arterial embolism, or by cerebral hypoperfusion.[3] Hemorrhagic stroke is caused by bleeding of blood vessels of the brain, either directly into the brain parenchyma or into the subarachnoid space surrounding brain tissue.[4][5] Risk factors for stroke include old age, high blood pressure, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), diabetes, high cholesterol, tobacco smoking and atrial fibrillation.[2] High blood pressure is the most important modifiable risk factor of stroke.[2]

A stroke is a medical emergency and can cause permanent neurological damage or death. An ischemic stroke is occasionally treated in a hospital with thrombolysis (also known as a "clot buster"), and some hemorrhagic strokes benefit from neurosurgery. Treatment to recover any lost function is termed stroke rehabilitation, ideally in a stroke unit and involving health professions such as speech and language therapy, physical therapy and occupational therapy. Prevention of recurrence may involve the administration of antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin, control of high blood pressure, and the use of statins. Some people may benefit from carotid endarterectomy and the use of anticoagulants.[2]

Stroke was the second most frequent cause of death worldwide in 2011, accounting for 6.2 million deaths (~11% of the total).[6] Approximately 17 million people had a stroke in 2010 and 33 million people have previously had a stroke and were still alive.[7] Between 1990 and 2010 the number of strokes decrease by approximately 10% in the developed world and increased by 10% in the developing world.[7] Overall two thirds of strokes occurred in those over 65 years old.[7]

Classification

A slice of brain from the autopsy of a person who suffered an acute middle cerebral artery (MCA) stroke

Strokes can be classified into two major categories: ischemic and hemorrhagic.[8] Ischemic strokes are caused by interruption of the blood supply, while hemorrhagic strokes result from the rupture of a blood vessel or an abnormal vascular structure. About 87% of strokes are ischemic, the rest being hemorrhagic. Some hemorrhages develop inside areas of ischemia, a condition known as "hemorrhagic transformation." It is unknown how many hemorrhagic strokes actually start as ischemic strokes.[2]

Definition

In the 1970s the World Health Organization defined stroke as a "neurological deficit of cerebrovascular cause that persists beyond 24 hours or is interrupted by death within 24 hours",[9] although the word "stroke" is centuries old. This definition was supposed to reflect the reversibility of tissue damage and was devised for the purpose, with the time frame of 24 hours being chosen arbitrarily. The 24-hour limit divides stroke from transient ischemic attack, which is a related syndrome of stroke symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hours.[2] With the availability of treatments which can reduce stroke severity when given early, many now prefer alternative terminology, such as brain attack and acute ischemic cerebrovascular syndrome (modeled after heart attack and acute coronary syndrome, respectively), to reflect the urgency of stroke symptoms and the need to act swiftly.[10]Ischemic

In an ischemic stroke, blood supply to part of the brain is decreased, leading to dysfunction of the brain tissue in that area. There are four reasons why this might happen:- Thrombosis (obstruction of a blood vessel by a blood clot forming locally)

- Embolism (obstruction due to an embolus from elsewhere in the body, see below),[2]

- Systemic hypoperfusion (general decrease in blood supply, e.g., in shock)[11]

- Venous thrombosis.[12]

There are various classification systems for acute ischemic stroke. The Oxford Community Stroke Project classification (OCSP, also known as the Bamford or Oxford classification) relies primarily on the initial symptoms; based on the extent of the symptoms, the stroke episode is classified as total anterior circulation infarct (TACI), partial anterior circulation infarct (PACI), lacunar infarct (LACI) or posterior circulation infarct (POCI). These four entities predict the extent of the stroke, the area of the brain that is affected, the underlying cause, and the prognosis.[14][15] The TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification is based on clinical symptoms as well as results of further investigations; on this basis, a stroke is classified as being due to (1) thrombosis or embolism due to atherosclerosis of a large artery, (2) embolism of cardiac origin, (3) occlusion of a small blood vessel, (4) other determined cause, (5) undetermined cause (two possible causes, no cause identified, or incomplete investigation).[16] Users of stimulant drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine are at a high risk for ischemic strokes.[17]

Hemorrhagic

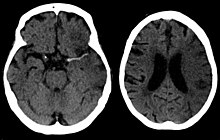

CT scan of an intraparenchymal bleed (bottom arrow) with surrounding edema (top arrow)

Intracranial hemorrhage is the accumulation of blood anywhere within the skull vault. A distinction is made between intra-axial hemorrhage (blood inside the brain) and extra-axial hemorrhage (blood inside the skull but outside the brain). Intra-axial hemorrhage is due to intraparenchymal hemorrhage or intraventricular hemorrhage (blood in the ventricular system). The main types of extra-axial hemorrhage are epidural hematoma (bleeding between the dura mater and the skull), subdural hematoma (in the subdural space) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (between the arachnoid mater and pia mater). Most of the hemorrhagic stroke syndromes have specific symptoms (e.g., headache, previous head injury).

Signs and symptoms

Stroke symptoms typically start suddenly, over seconds to minutes, and in most cases do not progress further. The symptoms depend on the area of the brain affected. The more extensive the area of brain affected, the more functions that are likely to be lost. Some forms of stroke can cause additional symptoms. For example, in intracranial hemorrhage, the affected area may compress other structures.Most forms of stroke are not associated with headache, apart from subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral venous thrombosis and occasionally intracerebral hemorrhage.

Early recognition

Various systems have been proposed to increase recognition of stroke. Different findings are able to predict the presence or absence of stroke to different degrees. Sudden-onset face weakness, arm drift (i.e., if a person, when asked to raise both arms, involuntarily lets one arm drift downward) and abnormal speech are the findings most likely to lead to the correct identification of a case of stroke increasing the likelihood by 5.5 when at least one of these is present). Similarly, when all three of these are absent, the likelihood of stroke is significantly decreased (– likelihood ratio of 0.39).[18]While these findings are not perfect for diagnosing stroke, the fact that they can be evaluated relatively rapidly and easily make them very valuable in the acute setting.

Proposed systems include FAST (face, arm, speech, and time),[19] as advocated by the Department of Health (United Kingdom) and the Stroke Association, the American Stroke Association, the National Stroke Association (US), the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)[20] and the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS).[21] Use of these scales is recommended by professional guidelines.[22]

For people referred to the emergency room, early recognition of stroke is deemed important as this can expedite diagnostic tests and treatments. A scoring system called ROSIER (recognition of stroke in the emergency room) is recommended for this purpose; it is based on features from the medical history and physical examination.[22][23]

Subtypes

If the area of the brain affected contains one of the three prominent central nervous system pathways—the spinothalamic tract, corticospinal tract, and dorsal column (medial lemniscus), symptoms may include:- hemiplegia and muscle weakness of the face

- numbness

- reduction in sensory or vibratory sensation

- initial flaccidity (hypotonicity), replaced by spasticity (hypertonicity), hyperreflexia, and obligatory synergies.[24]

In addition to the above CNS pathways, the brainstem gives rise to most of the twelve cranial nerves. A stroke affecting the brain stem and brain therefore can produce symptoms relating to deficits in these cranial nerves:

- altered smell, taste, hearing, or vision (total or partial)

- drooping of eyelid (ptosis) and weakness of ocular muscles

- decreased reflexes: gag, swallow, pupil reactivity to light

- decreased sensation and muscle weakness of the face

- balance problems and nystagmus

- altered breathing and heart rate

- weakness in sternocleidomastoid muscle with inability to turn head to one side

- weakness in tongue (inability to protrude and/or move from side to side)

- aphasia (difficulty with verbal expression, auditory comprehension, reading and/or writing; Broca's or Wernicke's area typically involved)

- dysarthria (motor speech disorder resulting from neurological injury)

- apraxia (altered voluntary movements)

- visual field defect

- memory deficits (involvement of temporal lobe)

- hemineglect (involvement of parietal lobe)

- disorganized thinking, confusion, hypersexual gestures (with involvement of frontal lobe)

- lack of insight of his or her, usually stroke-related, disability

Associated symptoms

Loss of consciousness, headache, and vomiting usually occurs more often in hemorrhagic stroke than in thrombosis because of the increased intracranial pressure from the leaking blood compressing the brain.If symptoms are maximal at onset, the cause is more likely to be a subarachnoid hemorrhage or an embolic stroke.

Causes

Thrombotic stroke

In thrombotic stroke a thrombus[25] (blood clot) usually forms around atherosclerotic plaques. Since blockage of the artery is gradual, onset of symptomatic thrombotic strokes is slower. A thrombus itself (even if non-occluding) can lead to an embolic stroke (see below) if the thrombus breaks off, at which point it is called an "embolus." Two types of thrombosis can cause stroke:

- Large vessel disease involves the common and internal carotids, vertebral, and the Circle of Willis.[26] Diseases that may form thrombi in the large vessels include (in descending incidence): atherosclerosis, vasoconstriction (tightening of the artery), aortic, carotid or vertebral artery dissection, various inflammatory diseases of the blood vessel wall (Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis, vasculitis), noninflammatory vasculopathy, Moyamoya disease and fibromuscular dysplasia.

- Small vessel disease involves the smaller arteries inside the brain: branches of the circle of Willis, middle cerebral artery, stem, and arteries arising from the distal vertebral and basilar artery.[27] Diseases that may form thrombi in the small vessels include (in descending incidence): lipohyalinosis (build-up of fatty hyaline matter in the blood vessel as a result of high blood pressure and aging) and fibrinoid degeneration (stroke involving these vessels are known as lacunar infarcts) and microatheroma (small atherosclerotic plaques).[28]

Embolic stroke

An embolic stroke refers to the blockage of an artery by an arterial embolus, a traveling particle or debris in the arterial bloodstream originating from elsewhere. An embolus is most frequently a thrombus, but it can also be a number of other substances including fat (e.g., from bone marrow in a broken bone), air, cancer cells or clumps of bacteria (usually from infectious endocarditis).[4]Because an embolus arises from elsewhere, local therapy solves the problem only temporarily. Thus, the source of the embolus must be identified. Because the embolic blockage is sudden in onset, symptoms usually are maximal at start. Also, symptoms may be transient as the embolus is partially resorbed and moves to a different location or dissipates altogether.

Emboli most commonly arise from the heart (especially in atrial fibrillation) but may originate from elsewhere in the arterial tree. In paradoxical embolism, a deep vein thrombosis embolizes through an atrial or ventricular septal defect in the heart into the brain.[4]

Cardiac causes can be distinguished between high and low-risk:[30]

- High risk: atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, rheumatic disease of the mitral or aortic valve disease, artificial heart valves, known cardiac thrombus of the atrium or ventricle, sick sinus syndrome, sustained atrial flutter, recent myocardial infarction, chronic myocardial infarction together with ejection fraction <28 a="" class="mw-redirect" href="/wiki/Congestive_heart_failure" percent="" symptomatic="" title="Congestive heart failure">congestive heart failure

Cerebral hypoperfusion

Cerebral hypoperfusion is the reduction of blood flow to all parts of the body. It is most commonly due to heart failure from cardiac arrest or arrhythmias, or from reduced cardiac output as a result of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pericardial effusion, or bleeding.[citation needed]Hypoxemia (low blood oxygen content) may precipitate the hypoperfusion. Because the reduction in blood flow is global, all parts of the brain may be affected, especially "watershed" areas - border zone regions supplied by the major cerebral arteries. A watershed stroke refers to the condition when blood supply to these areas is compromised. Blood flow to these areas does not necessarily stop, but instead it may lessen to the point where brain damage can occur.

Venous thrombosis

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis leads to stroke due to locally increased venous pressure, which exceeds the pressure generated by the arteries. Infarcts are more likely to undergo hemorrhagic transformation (leaking of blood into the damaged area) than other types of ischemic stroke.[12]Intracerebral hemorrhage

It generally occurs in small arteries or arterioles and is commonly due to hypertension,[31] intracranial vascular malformations (including cavernous angiomas or arteriovenous malformations), cerebral amyloid angiopathy, or infarcts into which secondary haemorrhage has occurred.[2] Other potential causes are trauma, bleeding disorders, amyloid angiopathy, illicit drug use (e.g., amphetamines or cocaine). The hematoma enlarges until pressure from surrounding tissue limits its growth, or until it decompresses by emptying into the ventricular system, CSF or the pial surface. A third of intracerebral bleed is into the brain's ventricles. ICH has a mortality rate of 44 percent after 30 days, higher than ischemic stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage (which technically may also be classified as a type of stroke[2]).Silent stroke

A silent stroke is a stroke that does not have any outward symptoms, and the patients are typically unaware they have suffered a stroke. Despite not causing identifiable symptoms, a silent stroke still damages the brain, and places the patient at increased risk for both transient ischemic attack and major stroke in the future. Conversely, those who have suffered a major stroke are also at risk of having silent strokes.[32] In a broad study in 1998, more than 11 million people were estimated to have experienced a stroke in the United States. Approximately 770,000 of these strokes were symptomatic and 11 million were first-ever silent MRI infarcts or hemorrhages. Silent strokes typically cause lesions which are detected via the use of neuroimaging such as MRI. Silent strokes are estimated to occur at five times the rate of symptomatic strokes.[33][34] The risk of silent stroke increases with age, but may also affect younger adults and children, especially those with acute anemia.[33][35]Pathophysiology

Ischemic

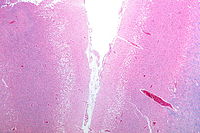

Micrograph showing cortical pseudolaminar necrosis, a finding seen in strokes on medical imaging and at autopsy. H&E-LFB stain.

Micrograph of the superficial cerebral cortex showing neuron loss and reactive astrocytes in a person that suffered a stroke. H&E-LFB stain.

Ischemic stroke occurs because of a loss of blood supply to part of the brain, initiating the ischemic cascade.[36] Brain tissue ceases to function if deprived of oxygen for more than 60 to 90 seconds, and after approximately three hours will suffer irreversible injury possibly leading to death of the tissue, i.e., infarction. (This is why fibrinolytics such as alteplase are given only until three hours since the onset of the stroke.) Atherosclerosis may disrupt the blood supply by narrowing the lumen of blood vessels leading to a reduction of blood flow, by causing the formation of blood clots within the vessel, or by releasing showers of small emboli through the disintegration of atherosclerotic plaques.[37] Embolic infarction occurs when emboli formed elsewhere in the circulatory system, typically in the heart as a consequence of atrial fibrillation, or in the carotid arteries, break off, enter the cerebral circulation, then lodge in and occlude brain blood vessels. Since blood vessels in the brain are now occluded, the brain becomes low in energy, and thus it resorts into using anaerobic metabolism within the region of brain tissue affected by ischemia. Anaerobic metabolism produces less adenosine triphosphate (ATP) but releases a by-product called lactic acid. Lactic acid is an irritant which could potentially destroy cells since it is an acid and disrupts the normal acid-base balance in the brain. The ischemia area is referred to as the "ischemic penumbra".[38]

As oxygen or glucose becomes depleted in ischemic brain tissue, the production of high energy phosphate compounds such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) fails, leading to failure of energy-dependent processes (such as ion pumping) necessary for tissue cell survival. This sets off a series of interrelated events that result in cellular injury and death. A major cause of neuronal injury is release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate. The concentration of glutamate outside the cells of the nervous system is normally kept low by so-called uptake carriers, which are powered by the concentration gradients of ions (mainly Na+) across the cell membrane. However, stroke cuts off the supply of oxygen and glucose which powers the ion pumps maintaining these gradients. As a result the transmembrane ion gradients run down, and glutamate transporters reverse their direction, releasing glutamate into the extracellular space. Glutamate acts on receptors in nerve cells (especially NMDA receptors), producing an influx of calcium which activates enzymes that digest the cells' proteins, lipids and nuclear material. Calcium influx can also lead to the failure of mitochondria, which can lead further toward energy depletion and may trigger cell death due to apoptosis.[citation needed]

Ischemia also induces production of oxygen free radicals and other reactive oxygen species. These react with and damage a number of cellular and extracellular elements. Damage to the blood vessel lining or endothelium is particularly important. In fact, many antioxidant neuroprotectants such as uric acid and NXY-059 work at the level of the endothelium and not in the brain per se. Free radicals also directly initiate elements of the apoptosis cascade by means of redox signaling.[citation needed]

These processes are the same for any type of ischemic tissue and are referred to collectively as the ischemic cascade. However, brain tissue is especially vulnerable to ischemia since it has little respiratory reserve and is completely dependent on aerobic metabolism, unlike most other organs.

In addition to injurious effects on brain cells, ischemia and infarction can result in loss of structural integrity of brain tissue and blood vessels, partly through the release of matrix metalloproteases, which are zinc- and calcium-dependent enzymes that break down collagen, hyaluronic acid, and other elements of connective tissue. Other proteases also contribute to this process. The loss of vascular structural integrity results in a breakdown of the protective blood brain barrier that contributes to cerebral edema, which can cause secondary progression of the brain injury.[citation needed]

Hemorrhagic

Bleeding within the skull cavity can occur from various causes. Subdural and epidural bleeding mostly are the result of trauma.[39] Hemorrhagic strokes arise from bleeding within the brain parenchyma or intraventricular spaces, and are classified based on their underlying pathology. Some examples of hemorrhagic stroke are hypertensive hemorrhage, ruptured aneurysm, ruptured AV fistula, transformation of prior ischemic infarction, and drug induced bleeding.[40] They result in tissue injury by causing compression of tissue from an expanding hematoma or hematomas. This can distort and injure tissue. In addition, the pressure may lead to a loss of blood supply to affected tissue with resulting infarction, and the blood released by brain hemorrhage appears to have direct toxic effects on brain tissue and vasculature.[29][41] Inflammation contributes to the secondary brain injury after hemorrhage.[41]Diagnosis

Stroke is diagnosed through several techniques: a neurological examination (such as the NIHSS), CT scans (most often without contrast enhancements) or MRI scans, Doppler ultrasound, and arteriography. The diagnosis of stroke itself is clinical, with assistance from the imaging techniques. Imaging techniques also assist in determining the subtypes and cause of stroke. There is yet no commonly used blood test for the stroke diagnosis itself, though blood tests may be of help in finding out the likely cause of stroke.[42]

Physical examination

A physical examination, including taking a medical history of the symptoms and a neurological status, helps giving an evaluation of the location and severity of a stroke. It can give a standard score on e.g., the NIH stroke scale.Imaging

For diagnosing ischemic stroke in the emergency setting:[43]- CT scans (without contrast enhancements)

- sensitivity= 16%

- specificity= 96%

- MRI scan

- sensitivity= 83%

- specificity= 98%

- CT scans (without contrast enhancements)

- sensitivity= 89%

- specificity= 100%

- MRI scan

- sensitivity= 81%

- specificity= 100%

For the assessment of stable stroke, nuclear medicine scans SPECT and PET/CT may be helpful. SPECT documents cerebral blood flow and PET with FDG isotope the metabolic activity of the neurons.

Underlying cause

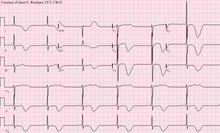

12-lead ECG of a patient with a stroke, showing large deeply inverted T-waves. Various ECG changes may occur in people with strokes and other brain disorders.

When a stroke has been diagnosed, various other studies may be performed to determine the underlying cause. With the current treatment and diagnosis options available, it is of particular importance to determine whether there is a peripheral source of emboli. Test selection may vary, since the cause of stroke varies with age, comorbidity and the clinical presentation. Commonly used techniques include:

- an ultrasound/doppler study of the carotid arteries (to detect carotid stenosis) or dissection of the precerebral arteries;

- an electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram (to identify arrhythmias and resultant clots in the heart which may spread to the brain vessels through the bloodstream);

- a Holter monitor study to identify intermittent arrhythmias;

- an angiogram of the cerebral vasculature (if a bleed is thought to have originated from an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation);

- blood tests to determine hypercholesterolemia, bleeding diathesis and some rarer causes such as homocysteinuria.

Prevention

Given the disease burden of strokes, prevention is an important public health concern.[45] Primary prevention is less effective than secondary prevention (as judged by the number needed to treat to prevent one stroke per year).[45] Recent guidelines detail the evidence for primary prevention in stroke.[46] In those who are otherwise healthy aspirin does not appear beneficial and thus is not recommended.[47] In people who have had a myocardial infarction or those with a high cardiovascular it provides some protection against a first stroke.[48][49] In those who have previously had a stroke, treatment with medications such as aspirin, clopidogrel and dipyridamole are beneficial.[48] The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against screening for carotid artery stenosis in those without symptoms.[50]Risk factors

The most important modifiable risk factors for stroke are high blood pressure and atrial fibrillation (although magnitude of this effect is small: the evidence from the Medical Research Council trials is that 833 patients have to be treated for 1 year to prevent one stroke[51][52]). Other modifiable risk factors include high blood cholesterol levels, diabetes, cigarette smoking[53][54] (active and passive), heavy alcohol consumption[55] and drug use,[56] lack of physical activity, obesity, processed red meat consumption[57] and unhealthy diet.[58] Alcohol use could predispose to ischemic stroke, and intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage via multiple mechanisms (for example via hypertension, atrial fibrillation, rebound thrombocytosis and platelet aggregation and clotting disturbances).[59]Drugs, most commonly amphetamines and cocaine, can induce stroke through intracranial vasculopathy and/or acute hypertension.[3][60]

No high-quality studies have shown the effectiveness of interventions aimed at weight reduction, promotion of regular exercise, reducing alcohol consumption or smoking cessation.[61] Nonetheless, given the large body of circumstantial evidence, best medical management for stroke includes advice on diet, exercise, smoking and alcohol use.[62] Medication or drug therapy is the most common method of stroke prevention; carotid endarterectomy can be a useful surgical method of preventing stroke.

Blood pressure

Hypertension (high blood pressure) accounts for 35-50% of stroke risk.[63] Blood pressure reduction of 10 mmHg systolic or 5 mmHg diastolic reduces the risk of stroke by ~40%.[64] Lowering blood pressure has been conclusively shown to prevent both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.[65][66] It is equally important in secondary prevention.[67] Even patients older than 80 years and those with isolated systolic hypertension benefit from antihypertensive therapy.[68][69][70] The available evidence does not show large differences in stroke prevention between antihypertensive drugs —therefore, other factors such as protection against other forms of cardiovascular disease should be considered and cost.[71][72] The routine use of beta-blockers following a stroke or TIA has not been shown to result in benefits.[73]Blood lipids

High cholesterol levels have been inconsistently associated with (ischemic) stroke.[66][74] Statins have been shown to reduce the risk of stroke by about 15%.[75] Since earlier meta-analyses of other lipid-lowering drugs did not show a decreased risk,[76] statins might exert their effect through mechanisms other than their lipid-lowering effects.[75]Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of stroke by 2 to 3 times. While intensive control of blood sugar has been shown to reduce microvascular complications such as nephropathy and retinopathy it has not been shown to reduce macrovascular complications such as stroke.[77][78]Anticoagulation drugs

Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin have been the mainstay of stroke prevention for over 50 years. However, several studies have shown that aspirin and antiplatelet drugs are highly effective in secondary prevention after a stroke or transient ischemic attack.[48] Low doses of aspirin (for example 75–150 mg) are as effective as high doses but have fewer side effects; the lowest effective dose remains unknown.[79] Thienopyridines (clopidogrel, ticlopidine) "might be slightly more effective" than aspirin and have a decreased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, but they are more expensive.[80] Their exact role remains controversial. Ticlopidine has more skin rash, diarrhea, neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.[80] Dipyridamole can be added to aspirin therapy to provide a small additional benefit, even though headache is a common side effect.[81]Low-dose aspirin is also effective for stroke prevention after sustaining a myocardial infarction.[49]

Those with atrial fibrillation have a 5% a year risk of stroke, and this risk is higher in those with valvular atrial fibrillation.[82] Depending on the stroke risk, anticoagulation with medications such as warfarin or aspirin is useful for prevention.[83] Except for in atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulants are not advised for stroke prevention —any benefit is offset by bleeding risk.[84]

In primary prevention however, antiplatelet drugs did not reduce the risk of ischemic stroke while increasing the risk of major bleeding.[85][86] Further studies are needed to investigate a possible protective effect of aspirin against ischemic stroke in women.[87][88]

Surgery

Carotid endarterectomy or carotid angioplasty can be used to remove atherosclerotic narrowing (stenosis) of the carotid artery. There is evidence supporting this procedure in selected cases.[62]Endarterectomy for a significant stenosis has been shown to be useful in the prevention of further strokes in those who have already had one.[89] Carotid artery stenting has not been shown to be equally useful.[90][91] Patients are selected for surgery based on age, gender, degree of stenosis, time since symptoms and patients' preferences.[62] Surgery is most efficient when not delayed too long —the risk of recurrent stroke in a patient who has a 50% or greater stenosis is up to 20% after 5 years, but endarterectomy reduces this risk to around 5%. The number of procedures needed to cure one patient was 5 for early surgery (within two weeks after the initial stroke), but 125 if delayed longer than 12 weeks.[92][93]

Screening for carotid artery narrowing has not been shown to be a useful screening test in the general population.[94] Studies of surgical intervention for carotid artery stenosis without symptoms have shown only a small decrease in the risk of stroke.[95][96] To be beneficial, the complication rate of the surgery should be kept below 4%. Even then, for 100 surgeries, 5 patients will benefit by avoiding stroke, 3 will develop stroke despite surgery, 3 will develop stroke or die due to the surgery itself, and 89 will remain stroke-free but would also have done so without intervention.[62]

Diet

Nutrition, specifically the Mediterranean-style diet, has the potential for decreasing the risk of having a stroke by more than half.[97] It does not appear that lowering levels of homocysteine with folic acid affects the risk of stroke.[98][99]Women

A number of specific recommendations have been made for women including: taking aspirin after the 11th week of pregnancy if there is a history of previous chronic high blood pressure, blood pressure medications in pregnancy if the blood pressure is greater than 150 mmHg systolic or greater than 100 mmHg diastolic. In those who have previously had preeclampsia other risk factors should be treated more aggressively.[100]Previous stroke or TIA

Keeping blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg is recommended.[101] Anticoagulation can prevent recurrent ischemic strokes. Among people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation can reduce stroke by 60% while antiplatelet agents can reduce stroke by 20%.[102] However, a recent meta-analysis suggests harm from anti-coagulation started early after an embolic stroke.[103] Stroke prevention treatment for atrial fibrillation is determined according to the CHADS/CHADS2 system.The most widely used anticoagulant to prevent thromboembolic stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation is the oral agent warfarin while a number of newer agents including dabigatran are alternatives which do not require prothrombin time monitoring.[101]

Anticoagulants, when used following stroke, should not be stopped for dental procedures.[104]

If studies show carotid stenosis, and the person has residual function in the affected side, carotid endarterectomy (surgical removal of the stenosis) may decrease the risk of recurrence if performed rapidly after stroke.

Management

Ischemic stroke

Definitive therapy is aimed at removing the blockage by breaking the clot down (thrombolysis), or by removing it mechanically (thrombectomy). The philosophical premise underlying the importance of rapid stroke intervention was crystallized as Time is Brain! in the early 1990s.[105] Years later, that same idea, that rapid cerebral blood flow restoration results in fewer brain cells dying, has been proved and quantified.[106]Tight control of blood sugars in the first few hours does not improve outcomes and may cause harm.[107] High blood pressure is also not typically lowered as this has not been found to be helpful.[108]

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis, such as with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), in acute ischemic stroke, when given given within three hours of symptom onset results in an overall benefit of 10% with respect to living without disability.[109][110] It does not, however, improve chances of survival.[109] Benefit is greater the earlier it is used.[111] Between three and four and a half hours the effects are less clear.[112] A 2014 review found a 5% increase in the number of people living without disability at three to six months; however, there was a 2% increased risk of death in the short term.[110] After four and a half hours thrombolysis worsens outcomes.[112] These benefits or lack of benefits occurred regardless of the age of the person treated.[113] There is no reliable way to determine who will have an intracranial hemorrhage post treatment versus who will not.[114]Its use is endorsed by the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Neurology as the recommended treatment for acute stroke within three hours of onset of symptoms as long as there are not other contraindications (such as abnormal lab values, high blood pressure, or recent surgery). This position for tPA is based upon the findings of two studies by one group of investigators[115] which showed that tPA improves the chances for a good neurological outcome. When administered within the first three hours thrombolysis improves functional outcome without affecting mortality.[116] 6.4% of people with large strokes developed substantial brain hemorrhage as a complication from being given tPA thus part of the reason for increased short term mortality.[117] Additionally, it is the position of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine that objective evidence regarding the efficacy, safety, and applicability of tPA for acute ischemic stroke is insufficient to warrant its classification as standard of care.[118]Intra-arterial fibrinolysis, where a catheter is passed up an artery into the brain and the medication is injected at the site of thrombosis, has been found to improve outcomes in people with acute ischemic stroke.[119]

Hemicraniectomy

Large territory strokes can cause significant edema of the brain with secondary brain injury in surrounding tissue. This phenomenon is mainly encountered in strokes of the middle cerebral artery territory, and is also called "malignant cerebral infarction" because it carries a dismal prognosis.Relief of the pressure may be attempted with medication, but some require hemicraniectomy, the temporary surgical removal of the skull on one side of the head. This decreases the risk of death, although some more people survive with disability who would otherwise have died.[120]

Hemorrhagic stroke

People with intracerebral hemorrhage require neurosurgical evaluation to detect and treat the cause of the bleeding, although many may not need surgery. Anticoagulants and antithrombotics, key in treating ischemic stroke, can make bleeding worse. People are monitored for changes in the level of consciousness, and their blood pressure, blood sugar, and oxygenation are kept at optimum levels.[citation needed]Stroke unit

Ideally, people who have had a stroke are admitted to a "stroke unit", a ward or dedicated area in hospital staffed by nurses and therapists with experience in stroke treatment. It has been shown that people admitted to a stroke unit have a higher chance of surviving than those admitted elsewhere in hospital, even if they are being cared for by doctors without experience in stroke.[2][121]When an acute stroke is suspected by history and physical examination, the goal of early assessment is to determine the cause. Treatment varies according to the underlying cause of the stroke, thromboembolic (ischemic) or hemorrhagic.

Rehabilitation

Stroke rehabilitation is the process by which those with disabling strokes undergo treatment to help them return to normal life as much as possible by regaining and relearning the skills of everyday living. It also aims to help the survivor understand and adapt to difficulties, prevent secondary complications and educate family members to play a supporting role.A rehabilitation team is usually multidisciplinary as it involves staff with different skills working together to help the patient. These include physicians trained in rehabilitation medicine, clinical pharmacists, nursing staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, and orthotists. Some teams may also include psychologists and social workers, since at least one third of the people manifest post stroke depression. Validated instruments such as the Barthel scale may be used to assess the likelihood of a stroke patient being able to manage at home with or without support subsequent to discharge from hospital.

Good nursing care is fundamental in maintaining skin care, feeding, hydration, positioning, and monitoring vital signs such as temperature, pulse, and blood pressure. Stroke rehabilitation begins almost immediately.

For most people with stroke, physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT) and speech-language pathology (SLP) are the cornerstones of the rehabilitation process. Often, assistive technology such as wheelchairs, walkers and canes may be beneficial. Many mobility problems can be improved by the use of ankle foot orthoses.[122] PT and OT have overlapping areas of expertise, however PT focuses on joint range of motion and strength by performing exercises and re-learning functional tasks such as bed mobility, transferring, walking and other gross motor functions. Physiotherapists can also work with patients to improve awareness and use of the hemiplegic side. Rehabilitation involves working on the ability to produce strong movements or the ability to perform tasks using normal patterns. Emphasis is often concentrated on functional tasks and patient’s goals. One example physiotherapists employ to promote motor learning involves constraint-induced movement therapy. Through continuous practice the patient relearns to use and adapt the hemiplegic limb during functional activities to create lasting permanent changes.[123] OT is involved in training to help relearn everyday activities known as the Activities of daily living (ADLs) such as eating, drinking, dressing, bathing, cooking, reading and writing, and toileting. Speech and language therapy is appropriate for patients with the speech production disorders: dysarthria[124] and apraxia of speech,[125] aphasia,[126] cognitive-communication impairments and/or dysphagia (problems with swallowing).

Patients may have particular problems, such as dysphagia, which can cause swallowed material to pass into the lungs and cause aspiration pneumonia. The condition may improve with time, but in the interim, a nasogastric tube may be inserted, enabling liquid food to be given directly into the stomach. If swallowing is still deemed unsafe, then a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is passed and this can remain indefinitely.

Treatment of spasticity related to stroke often involves early mobilizations, commonly performed by a physiotherapist, combined with elongation of spastic muscles and sustained stretching through various positionings.[24] Gaining initial improvement in range of motion is often achieved through rhythmic rotational patterns associated with the affected limb.[24] After full range has been achieved by the therapist, the limb should be positioned in the lengthened positions to prevent against further contractures, skin breakdown, and disuse of the limb with the use of splints or other tools to stabilize the joint.[24] Cold in the form of ice wraps or ice packs have been proven to briefly reduce spasticity by temporarily dampening neural firing rates.[24] Electrical stimulation to the antagonist muscles or vibrations has also been used with some success.[24]

Stroke rehabilitation should be started as quickly as possible and can last anywhere from a few days to over a year. Most return of function is seen in the first few months, and then improvement falls off with the "window" considered officially by U.S. state rehabilitation units and others to be closed after six months, with little chance of further improvement. However, patients have been known to continue to improve for years, regaining and strengthening abilities like writing, walking, running, and talking. Daily rehabilitation exercises should continue to be part of the stroke patient's routine. Complete recovery is unusual but not impossible and most patients will improve to some extent: proper diet and exercise are known to help the brain to recover.

Some current and future therapy methods include the use of virtual reality and video games for rehabilitation. These forms of rehabilitation offer potential for motivating patients to perform specific therapy tasks that many other forms do not.[127] Many clinics and hospitals are adopting the use of these off-the-shelf devices for exercise, social interaction and rehabilitation because they are affordable, accessible and can be used within the clinic and home.[127]

Other novel non-invasive rehabilitation methods are currently being developed to augment physical therapy to improve motor function of stroke patients, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS)[128] and robotic therapies.[129]

A stroke can also reduce people's general fitness.[130] Reduced fitness can reduce capacity for rehabilitation as well as general health.[131] A systematic review found that there are inadequate long-term data about the effects of exercise and training on death, dependence and disability after a stroke.[130] However, cardiorespiratory training added to walking programs in rehabilitation can improve speed, tolerance and independence during walking.[130]

Prognosis

Disability affects 75% of stroke survivors enough to decrease their employability.[132] Stroke can affect peoples physically, mentally, emotionally, or a combination of the three. The results of stroke vary widely depending on size and location of the lesion.[133] Dysfunctions correspond to areas in the brain that have been damaged.Some of the physical disabilities that can result from stroke include muscle weakness, numbness, pressure sores, pneumonia, incontinence, apraxia (inability to perform learned movements), difficulties carrying out daily activities, appetite loss, speech loss, vision loss and pain. If the stroke is severe enough, or in a certain location such as parts of the brainstem, coma or death can result.

Emotional problems following a stroke can be due to direct damage to emotional centers in the brain or from frustration and difficulty adapting to new limitations. Post-stroke emotional difficulties include anxiety, panic attacks, flat affect (failure to express emotions), mania, apathy and psychosis. Other difficulties may include a decreased ability to communicate emotions through facial expression, body language and voice.[134]

Disruption in self-identity, relationships with others, and emotional well-being can lead to social consequences after stroke due to the lack of ability to communicate. Many patients who experience communication impairments after a stroke find it more difficult to cope with the social issues rather than physical impairments. Broader aspects of care must address the emotional impact speech impairment has on those who experience difficulties with speech after a stroke. [135] Those who experience a stroke are at risk for paralysis which could result in a self disturbed body image which may also lead to other social issues. [136]

30 to 50% of stroke survivors suffer post-stroke depression, which is characterized by lethargy, irritability, sleep disturbances, lowered self-esteem and withdrawal.[137] Depression can reduce motivation and worsen outcome, but can be treated with antidepressants.

Emotional lability, another consequence of stroke, causes the patient to switch quickly between emotional highs and lows and to express emotions inappropriately, for instance with an excess of laughing or crying with little or no provocation. While these expressions of emotion usually correspond to the patient's actual emotions, a more severe form of emotional lability causes patients to laugh and cry pathologically, without regard to context or emotion.[132] Some patients show the opposite of what they feel, for example crying when they are happy.[138] Emotional lability occurs in about 20% of stroke patients.

Cognitive deficits resulting from stroke include perceptual disorders, Aphasia,[139] dementia,[140] and problems with attention[141] and memory.[142] A stroke sufferer may be unaware of his or her own disabilities, a condition called anosognosia. In a condition called hemispatial neglect, a patient is unable to attend to anything on the side of space opposite to the damaged hemisphere.

Cognitive and psychological outcome after a stroke can be affected by the age at which the stroke happened, pre-stroke baseline intellectual functioning, psychiatric history and whether there is pre-existing brain pathology.[143]

Up to 10% of people following a stroke develop seizures, most commonly in the week subsequent to the event; the severity of the stroke increases the likelihood of a seizure.[144][145]

Epidemiology

Disability-adjusted life year for cerebral vascular disease per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[146]

no data

<250

250-425

425-600

600-775

775-950

950-1125

|

1125-1300

1300-1475

1475-1650

1650-1825

1825-2000

>2000

|

Stroke was the second most frequent cause of death worldwide in 2011, accounting for 6.2 million deaths (~11% of the total).[6] Approximately 17 million people had a stroke in 2010 and 33 million people have previously had a stroke and were still alive.[7] Between 1990 and 2010 the number of strokes decrease by approximately 10% in the developed world and increased by 10% in the developing world.[7] Overall two thirds of strokes occurred in those over 65 years old.[7]

It is ranked after heart disease and before cancer.[2] In the United States stroke is a leading cause of disability, and recently declined from the third leading to the fourth leading cause of death.[147] Geographic disparities in stroke incidence have been observed, including the existence of a "stroke belt" in the southeastern United States, but causes of these disparities have not been explained.

The incidence of stroke increases exponentially from 30 years of age, and etiology varies by age.[148] Advanced age is one of the most significant stroke risk factors. 95% of strokes occur in people age 45 and older, and two-thirds of strokes occur in those over the age of 65.[137][29] A person's risk of dying if he or she does have a stroke also increases with age. However, stroke can occur at any age, including in childhood.

Family members may have a genetic tendency for stroke or share a lifestyle that contributes to stroke. Higher levels of Von Willebrand factor are more common amongst people who have had ischemic stroke for the first time.[149] The results of this study found that the only significant genetic factor was the person's blood type. Having had a stroke in the past greatly increases one's risk of future strokes.

Men are 25% more likely to suffer strokes than women,[29] yet 60% of deaths from stroke occur in women.[138] Since women live longer, they are older on average when they have their strokes and thus more often killed (NIMH 2002).[29] Some risk factors for stroke apply only to women. Primary among these are pregnancy, childbirth, menopause and the treatment thereof (HRT).

History

Episodes of stroke and familial stroke have been reported from the 2nd millennium BC onward in ancient Mesopotamia and Persia.[150] Hippocrates (460 to 370 BC) was first to describe the phenomenon of sudden paralysis that is often associated with ischemia. Apoplexy, from the Greek word meaning "struck down with violence," first appeared in Hippocratic writings to describe this phenomenon.[151][152] The word stroke was used as a synonym for apoplectic seizure as early as 1599,[153] and is a fairly literal translation of the Greek term.

In 1658, in his Apoplexia, Johann Jacob Wepfer (1620–1695) identified the cause of hemorrhagic stroke when he suggested that people who had died of apoplexy had bleeding in their brains.[151][29] Wepfer also identified the main arteries supplying the brain, the vertebral and carotid arteries, and identified the cause of ischemic stroke [also known as cerebral infarction] when he suggested that apoplexy might be caused by a blockage to those vessels.[29] Rudolf Virchow first described the mechanism of thromboembolism as a major factor.[154]

The term cerebrovascular accident was introduced in 1927, reflecting a "growing awareness and acceptance of vascular theories and (...) recognition of the consequences of a sudden disruption in the vascular supply of the brain".[155] Its use is now discouraged by a number of neurology textbooks, reasoning that the connotation of fortuitousness carried by the word accident insufficiently highlights the modifiability of the underlying risk factors.[156][157][158] Cerebrovascular insult may be used interchangeably.[159]

The term brain attack was introduced for use to underline the acute nature of stroke according to the American Stroke Association,[159] who since 1990 have used the term,[160] and is used colloquially to refer to both ischemic as well as hemorrhagic stroke.[161]

Research

Angioplasty and stenting

Angioplasty and stenting have begun to be looked at as possible viable options in treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Intra-cranial stenting in symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis, the rate of technical success (reduction to stenosis of <50%) ranged from 90-98%, and the rate of major peri-procedural complications ranged from 4-10%. The rates of restenosis and/or stroke following the treatment were also favorable. This data suggests that a randomized controlled trial is needed to more completely evaluate the possible therapeutic advantage of this preventative measure.[162]Mechanical thrombectomy

Removal of the clot may be attempted in those where it occurs within a large blood vessel and may be an option for those who either are not eligible for or do not improve with intravenous thrombolytics.[163] Significant complications occur in about 7%.[164] As of October 2013[update], trials have not shown positive results.[165]

Neuroprotection

Drugs that scavenge reactive oxygen species, inhibit apoptosis, or inhibit excitatory neurotransmitters have been shown experimentally to reduce tissue injury caused by ischemia. Agents that work in this way are referred to as being neuroprotective. Until recently, human clinical trials with neuroprotective agents have failed, with the probable exception of deep barbiturate coma. However, more recently NXY-059, the disulfonyl derivative of the radical-scavengin phenylbutylnitrone, is reported to be neuroprotective in stroke.[166] This agent appears to work at the level of the blood vessel lining or endothelium. Unfortunately, after producing favorable results in one large-scale clinical trial, a second trial failed to show favorable results.[29] Benefit of NXY-059 is questionable.[167]Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been studied as a possible protective measure, but is currently not thought to be beneficial.[168]