The Chinese room argument holds that a program cannot give a computer a "mind", "understanding" or "consciousness",[a] regardless of how intelligently or human-like the program may make the computer behave. The argument was first presented by philosopher John Searle in his paper, "Minds, Brains, and Programs", published in Behavioral and Brain Sciences in 1980. It has been widely discussed in the years since.[1] The centerpiece of the argument is a thought experiment known as the Chinese room.[2]

The argument is directed against the philosophical positions of functionalism and computationalism,[3] which hold that the mind may be viewed as an information-processing system operating on formal symbols. Specifically, the argument is intended to refute a position Searle calls

Strong AI:

The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds.[b]Although it was originally presented in reaction to the statements of artificial intelligence (AI) researchers, it is not an argument against the goals of AI research, because it does not limit the amount of intelligence a machine can display.[4] The argument applies only to digital computers running programs and does not apply to machines in general.[5]

Chinese room thought experiment

John Searle

Searle's thought experiment begins with this hypothetical premise: suppose that artificial intelligence research has succeeded in constructing a computer that behaves as if it understands Chinese. It takes Chinese characters as input and, by following the instructions of a computer program, produces other Chinese characters, which it presents as output. Suppose, says Searle, that this computer performs its task so convincingly that it comfortably passes the Turing test: it convinces a human Chinese speaker that the program is itself a live Chinese speaker. To all of the questions that the person asks, it makes appropriate responses, such that any Chinese speaker would be convinced that they are talking to another Chinese-speaking human being.

The question Searle wants to answer is this: does the machine literally "understand" Chinese? Or is it merely simulating the ability to understand Chinese?[6][c] Searle calls the first position "strong AI" and the latter "weak AI".[d]

Searle then supposes that he is in a closed room and has a book with an English version of the computer program, along with sufficient paper, pencils, erasers, and filing cabinets. Searle could receive Chinese characters through a slot in the door, process them according to the program's instructions, and produce Chinese characters as output. If the computer had passed the Turing test this way, it follows, says Searle, that he would do so as well, simply by running the program manually.

Searle asserts that there is no essential difference between the roles of the computer and himself in the experiment. Each simply follows a program, step-by-step, producing a behavior which is then interpreted as demonstrating intelligent conversation. However, Searle would not be able to understand the conversation. ("I don't speak a word of Chinese,"[9] he points out.) Therefore, he argues, it follows that the computer would not be able to understand the conversation either.

Searle argues that, without "understanding" (or "intentionality"), we cannot describe what the machine is doing as "thinking" and, since it does not think, it does not have a "mind" in anything like the normal sense of the word. Therefore, he concludes that "strong AI" is false.

History

Gottfried Leibniz made a similar argument in 1714 against mechanism (the position that the mind is a machine and nothing more). Leibniz used the thought experiment of expanding the brain until it was the size of a mill.[10] Leibniz found it difficult to imagine that a "mind" capable of "perception" could be constructed using only mechanical processes.[e] In 1974, Lawrence Davis imagined duplicating the brain using telephone lines and offices staffed by people, and in 1978 Ned Block envisioned the entire population of China involved in such a brain simulation. This thought experiment is called the China brain, also the "Chinese Nation" or the "Chinese Gym".[11]The Chinese Room Argument was introduced in Searle's 1980 paper "Minds, Brains, and Programs", published in Behavioral and Brain Sciences.[12] It eventually became the journal's "most influential target article",[1] generating an enormous number of commentaries and responses in the ensuing decades, and Searle has continued to defend and refine the argument in many papers, popular articles and books. David Cole writes that "the Chinese Room argument has probably been the most widely discussed philosophical argument in cognitive science to appear in the past 25 years".[13]

Most of the discussion consists of attempts to refute it. "The overwhelming majority," notes BBS editor Stevan Harnad,[f] "still think that the Chinese Room Argument is dead wrong."[14] The sheer volume of the literature that has grown up around it inspired Pat Hayes to comment that the field of cognitive science ought to be redefined as "the ongoing research program of showing Searle's Chinese Room Argument to be false".[15]

Searle's argument has become "something of a classic in cognitive science," according to Harnad.[14] Varol Akman agrees, and has described the original paper as "an exemplar of philosophical clarity and purity".[16]

Philosophy

Although the Chinese Room argument was originally presented in reaction to the statements of AI researchers, philosophers have come to view it as an important part of the philosophy of mind. It is a challenge to functionalism and the computational theory of mind,[g] and is related to such questions as the mind–body problem, the problem of other minds, the symbol-grounding problem, and the hard problem of consciousness.[a]Strong AI

Searle identified a philosophical position he calls "strong AI":The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds.[b]The definition hinges on the distinction between simulating a mind and actually having a mind. Searle writes that "according to Strong AI, the correct simulation really is a mind. According to Weak AI, the correct simulation is a model of the mind."[7]

The position is implicit in some of the statements of early AI researchers and analysts. For example, in 1955, AI founder Herbert A. Simon declared that "there are now in the world machines that think, that learn and create"[22][h] and claimed that they had "solved the venerable mind–body problem, explaining how a system composed of matter can have the properties of mind."[23] John Haugeland wrote that "AI wants only the genuine article: machines with minds, in the full and literal sense. This is not science fiction, but real science, based on a theoretical conception as deep as it is daring: namely, we are, at root, computers ourselves."[24]

Searle also ascribes the following positions to advocates of strong AI:

- AI systems can be used to explain the mind;[d]

- The study of the brain is irrelevant to the study of the mind;[i] and

- The Turing test is adequate for establishing the existence of mental states.[j]

Strong AI as computationalism or functionalism

In more recent presentations of the Chinese room argument, Searle has identified "strong AI" as "computer functionalism" (a term he attributes to Daniel Dennett).[3][29] Functionalism is a position in modern philosophy of mind that holds that we can define mental phenomena (such as beliefs, desires, and perceptions) by describing their functions in relation to each other and to the outside world. Because a computer program can accurately represent functional relationships as relationships between symbols, a computer can have mental phenomena if it runs the right program, according to functionalism.Stevan Harnad argues that Searle's depictions of strong AI can be reformulated as "recognizable tenets of computationalism, a position (unlike "strong AI") that is actually held by many thinkers, and hence one worth refuting."[30] Computationalism[k] is the position in the philosophy of mind which argues that the mind can be accurately described as an information-processing system.

Each of the following, according to Harnad, is a "tenet" of computationalism:[33]

- Mental states are computational states (which is why computers can have mental states and help to explain the mind);

- Computational states are implementation-independent — in other words, it is the software that determines the computational state, not the hardware (which is why the brain, being hardware, is irrelevant); and that

- Since implementation is unimportant, the only empirical data that matters is how the system functions; hence the Turing test is definitive.

Strong AI vs. biological naturalism

Searle holds a philosophical position he calls "biological naturalism": that consciousness[a] and understanding require specific biological machinery that are found in brains. He writes "brains cause minds"[5] and that "actual human mental phenomena [are] dependent on actual physical–chemical properties of actual human brains".[34] Searle argues that this machinery (known to neuroscience as the "neural correlates of consciousness") must have some (unspecified) "causal powers" that permit the human experience of consciousness.[35] Searle's faith in the existence of these powers has been criticized.[l]Searle does not disagree with the notion that machines can have consciousness and understanding, because, as he writes, "we are precisely such machines".[5] Searle holds that the brain is, in fact, a machine, but that the brain gives rise to consciousness and understanding using machinery that is non-computational. If neuroscience is able to isolate the mechanical process that gives rise to consciousness, then Searle grants that it may be possible to create machines that have consciousness and understanding. However, without the specific machinery required, Searle does not believe that consciousness can occur.

Biological naturalism implies that one cannot determine if the experience of consciousness is occurring merely by examining how a system functions, because the specific machinery of the brain is essential. Thus, biological naturalism is directly opposed to both behaviorism and functionalism (including "computer functionalism" or "strong AI").[36] Biological naturalism is similar to identity theory (the position that mental states are "identical to" or "composed of" neurological events); however, Searle has specific technical objections to identity theory.[37][m] Searle's biological naturalism and strong AI are both opposed to Cartesian dualism,[36] the classical idea that the brain and mind are made of different "substances". Indeed, Searle accuses strong AI of dualism, writing that "strong AI only makes sense given the dualistic assumption that, where the mind is concerned, the brain doesn't matter."[25]

Consciousness

Searle's original presentation emphasized "understanding"—that is, mental states with what philosophers call "intentionality"—and did not directly address other closely related ideas such as "consciousness". However, in more recent presentations Searle has included consciousness as the real target of the argument.[3]Computational models of consciousness are not sufficient by themselves for consciousness. The computational model for consciousness stands to consciousness in the same way the computational model of anything stands to the domain being modelled. Nobody supposes that the computational model of rainstorms in London will leave us all wet. But they make the mistake of supposing that the computational model of consciousness is somehow conscious. It is the same mistake in both cases.[38]David Chalmers writes "it is fairly clear that consciousness is at the root of the matter" of the Chinese room.[39]

— John R. Searle, Consciousness and Language, p. 16

Colin McGinn argues that the Chinese room provides strong evidence that the hard problem of consciousness is fundamentally insoluble. The argument, to be clear, is not about whether a machine can be conscious, but about whether it (or anything else for that matter) can be shown to be conscious. It is plain that any other method of probing the occupant of a Chinese room has the same difficulties in principle as exchanging questions and answers in Chinese. It is simply not possible to divine whether a conscious agency or some clever simulation inhabits the room.[40]

Searle argues that this is only true for an observer outside of the room. The whole point of the thought experiment is to put someone inside the room, where they can directly observe the operations of consciousness. Searle claims that from his vantage point within the room there is nothing he can see that could imaginably give rise to consciousness, other than himself, and clearly he does not have a mind that can speak Chinese.

Applied Ethics

Sitting in the Combat Information Center aboard a warship - proposed as a real-life analog to the Chinese Room

Patrick Hew used the Chinese Room argument to deduce requirements from military command and control systems if they are to preserve a commander's moral agency. He drew an analogy between a commander in their command center and the person in the Chinese Room, and analyzed it under a reading of Aristotle’s notions of 'compulsory' and 'ignorance'. Information could be 'down converted' from meaning to symbols, and manipulated symbolically, but moral agency could be undermined if there was inadequate 'up conversion' into meaning. Hew cited examples from the USS Vincennes incident.[41]

Computer science

The Chinese room argument is primarily an argument in the philosophy of mind, and both major computer scientists and artificial intelligence researchers consider it irrelevant to their fields.[4] However, several concepts developed by computer scientists are essential to understanding the argument, including symbol processing, Turing machines, Turing completeness, and the Turing test.Strong AI vs. AI research

Searle's arguments are not usually considered an issue for AI research. Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig observe that most AI researchers "don't care about the strong AI hypothesis—as long as the program works, they don't care whether you call it a simulation of intelligence or real intelligence."[4] The primary mission of artificial intelligence research is only to create useful systems that act intelligently, and it does not matter if the intelligence is "merely" a simulation.Searle does not disagree that AI research can create machines that are capable of highly intelligent behavior. The Chinese room argument leaves open the possibility that a digital machine could be built that acts more intelligently than a person, but does not have a mind or intentionality in the same way that brains do. Indeed, Searle writes that "the Chinese room argument ... assumes complete success on the part of artificial intelligence in simulating human cognition."[42]

Searle's "strong AI" should not be confused with "strong AI" as defined by Ray Kurzweil and other futurists,[43] who use the term to describe machine intelligence that rivals or exceeds human intelligence. Kurzweil is concerned primarily with the amount of intelligence displayed by the machine, whereas Searle's argument sets no limit on this. Searle argues that even a super-intelligent machine would not necessarily have a mind and consciousness.

Turing test

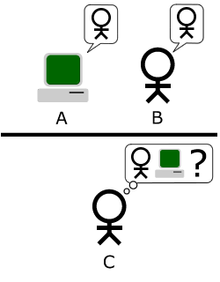

The "standard interpretation" of the Turing Test, in which player C, the

interrogator, is given the task of trying to determine which player – A

or B – is a computer and which is a human. The interrogator is limited

to using the responses to written questions to make the determination.

Image adapted from Saygin, 2000.[44]

The Chinese room implements a version of the Turing test.[45] Alan Turing introduced the test in 1950 to help answer the question "can machines think?" In the standard version, a human judge engages in a natural language conversation with a human and a machine designed to generate performance indistinguishable from that of a human being. All participants are separated from one another. If the judge cannot reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine is said to have passed the test.

Turing then considered each possible objection to the proposal "machines can think", and found that there are simple, obvious answers if the question is de-mystified in this way. He did not, however, intend for the test to measure for the presence of "consciousness" or "understanding". He did not believe this was relevant to the issues that he was addressing. He wrote:

I do not wish to give the impression that I think there is no mystery about consciousness. There is, for instance, something of a paradox connected with any attempt to localise it. But I do not think these mysteries necessarily need to be solved before we can answer the question with which we are concerned in this paper.[45]To Searle, as a philosopher investigating in the nature of mind and consciousness, these are the relevant mysteries. The Chinese room is designed to show that the Turing test is insufficient to detect the presence of consciousness, even if the room can behave or function as a conscious mind would.

Symbol processing

The Chinese room (and all modern computers) manipulate physical objects in order to carry out calculations and do simulations. AI researchers Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon called this kind of machine a physical symbol system. It is also equivalent to the formal systems used in the field of mathematical logic.Searle emphasizes the fact that this kind of symbol manipulation is syntactic (borrowing a term from the study of grammar). The computer manipulates the symbols using a form of syntax rules, without any knowledge of the symbol's semantics (that is, their meaning).

Newell and Simon had conjectured that a physical symbol system (such as a digital computer) had all the necessary machinery for "general intelligent action", or, as it is known today, artificial general intelligence. They framed this as a philosophical position, the physical symbol system hypothesis: "A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means for general intelligent action."[46][47] The Chinese room argument does not refute this, because it is framed in terms of "intelligent action", i.e. the external behavior of the machine, rather than the presence or absence of understanding, consciousness and mind.

Chinese room and Turing completeness

The Chinese room has a design analogous to that of a modern computer. It has a Von Neumann architecture, which consists of a program (the book of instructions), some memory (the papers and file cabinets), a CPU which follows the instructions (the man), and a means to write symbols in memory (the pencil and eraser). A machine with this design is known in theoretical computer science as "Turing complete", because it has the necessary machinery to carry out any computation that a Turing machine can do, and therefore it is capable of doing a step-by-step simulation of any other digital machine, given enough memory and time. Alan Turing writes, "all digital computers are in a sense equivalent."[48] The widely accepted Church-Turing thesis holds that any function computable by an effective procedure is computable by a Turing machine.The Turing completeness of the Chinese room implies that it can do whatever any other digital computer can do (albeit much, much more slowly). Thus, if the Chinese room does not or can not contain a Chinese-speaking mind, then no other digital computer can contain a mind. Some replies to Searle begin by arguing that the room, as described, cannot have a Chinese-speaking mind. Arguments of this form, according to Stevan Harnad, are "no refutation (but rather an affirmation)"[49] of the Chinese room argument, because these arguments actually imply that no digital computers can have a mind.[27]

There are some critics, such as Hanoch Ben-Yami, who argue that the Chinese room cannot simulate all the abilities of a digital computer, such as being able to determine the current time.[50]

Complete argument

Searle has produced a more formal version of the argument of which the Chinese Room forms a part. He presented the first version in 1984. The version given below is from 1990.[51][n] The only part of the argument which should be controversial is A3 and it is this point which the Chinese room thought experiment is intended to prove.[o]He begins with three axioms:

- (A1) "Programs are formal (syntactic)."

- (A2) "Minds have mental contents (semantics)."

- Unlike the symbols used by a program, our thoughts have meaning: they represent things and we know what it is they represent.

- (A3) "Syntax by itself is neither constitutive of nor sufficient for semantics."

- This is what the Chinese room thought experiment is intended to prove: the Chinese room has syntax (because there is a man in there moving symbols around). The Chinese room has no semantics (because, according to Searle, there is no one or nothing in the room that understands what the symbols mean). Therefore, having syntax is not enough to generate semantics.

- (C1) Programs are neither constitutive of nor sufficient for minds.

- This should follow without controversy from the first three: Programs don't have semantics. Programs have only syntax, and syntax is insufficient for semantics. Every mind has semantics. Therefore no programs are minds.

- (A4) Brains cause minds.

- (C2) Any other system capable of causing minds would have to have causal powers (at least) equivalent to those of brains.

- Brains must have something that causes a mind to exist. Science has yet to determine exactly what it is, but it must exist, because minds exist. Searle calls it "causal powers". "Causal powers" is whatever the brain uses to create a mind. If anything else can cause a mind to exist, it must have "equivalent causal powers". "Equivalent causal powers" is whatever else that could be used to make a mind.

- (C3) Any artifact that produced mental phenomena, any artificial

brain, would have to be able to duplicate the specific causal powers of

brains, and it could not do that just by running a formal program.

- This follows from C1 and C2: Since no program can produce a mind, and "equivalent causal powers" produce minds, it follows that programs do not have "equivalent causal powers."

- (C4) The way that human brains actually produce mental phenomena cannot be solely by virtue of running a computer program.

- Since programs do not have "equivalent causal powers", "equivalent causal powers" produce minds, and brains produce minds, it follows that brains do not use programs to produce minds.

Replies

Replies to Searle's argument may be classified according to what they claim to show:[p]- Those which identify who speaks Chinese

- Those which demonstrate how meaningless symbols can become meaningful

- Those which suggest that the Chinese room should be redesigned in some way

- Those which contend that Searle's argument is misleading

- Those which argue that the argument makes false assumptions about subjective conscious experience and therefore proves nothing

Systems and virtual mind replies: finding the mind

These replies attempt to answer the question: since the man in the room doesn't speak Chinese, where is the "mind" that does? These replies address the key ontological issues of mind vs. body and simulation vs. reality. All of the replies that identify the mind in the room are versions of "the system reply".- System reply

- The basic "systems reply" argues that it is the "whole system" that understands Chinese.[56][q] While the man understands only English, when he is combined with the program, scratch paper, pencils and file cabinets, they form a system that can understand Chinese. "Here, understanding is not being ascribed to the mere individual; rather it is being ascribed to this whole system of which he is a part" Searle explains.[28] The fact that man does not understand Chinese is irrelevant, because it is only the system as a whole that matters.

Searle then responds by simplifying this list of physical objects: he asks what happens if the man memorizes the rules and keeps track of everything in his head? Then the whole system consists of just one object: the man himself. Searle argues that if the man doesn't understand Chinese then the system doesn't understand Chinese either because now "the system" and "the man" both describe exactly the same object.[28]

Critics of Searle's response argue that the program has allowed the man to have two minds in one head.[who?] If we assume a "mind" is a form of information processing, then the theory of computation can account for two computations occurring at once, namely (1) the computation for universal programmability (which is the function instantiated by the person and note-taking materials independently from any particular program contents) and (2) the computation of the Turing machine that is described by the program (which is instantiated by everything including the specific program).[58] The theory of computation thus formally explains the open possibility that the second computation in the Chinese Room could entail a human-equivalent semantic understanding of the Chinese inputs. The focus belongs on the program's Turing machine rather than on the person's.[59] However, from Searle's perspective, this argument is circular. The question at issue is whether consciousness is a form of information processing, and this reply requires that we make that assumption.

More sophisticated versions of the systems reply try to identify more precisely what "the system" is and they differ in exactly how they describe it. According to these replies,[who?] the "mind that speaks Chinese" could be such things as: the "software", a "program", a "running program", a simulation of the "neural correlates of consciousness", the "functional system", a "simulated mind", an "emergent property", or "a virtual mind" (Marvin Minsky's version of the systems reply, described below).

- Virtual mind reply

- The term "virtual" is used in computer science to describe an object that appears to exist "in" a computer (or computer network) only because software makes it appear to exist. The objects "inside" computers (including files, folders, and so on) are all "virtual", except for the computer's electronic components. Similarly, Minsky argues, a computer may contain a "mind" that is virtual in the same sense as virtual machines, virtual communities and virtual reality.[r]

- To clarify the distinction between the simple systems reply given above and virtual mind reply, David Cole notes that two simulations could be running on one system at the same time: one speaking Chinese and one speaking Korean. While there is only one system, there can be multiple "virtual minds," thus the "system" cannot be the "mind".[63]

These replies provide an explanation of exactly who it is that understands Chinese. If there is something besides the man in the room that can understand Chinese, Searle can't argue that (1) the man doesn't understand Chinese, therefore (2) nothing in the room understands Chinese. This, according to those who make this reply, shows that Searle's argument fails to prove that "strong AI" is false.[s]

However, the replies, by themselves, do not prove that strong AI is true, either: they provide no evidence that the system (or the virtual mind) understands Chinese, other than the hypothetical premise that it passes the Turing Test. As Searle writes "the systems reply simply begs the question by insisting that system must understand Chinese."[28]

Robot and semantics replies: finding the meaning

As far as the person in the room is concerned, the symbols are just meaningless "squiggles." But if the Chinese room really "understands" what it is saying, then the symbols must get their meaning from somewhere. These arguments attempt to connect the symbols to the things they symbolize. These replies address Searle's concerns about intentionality, symbol grounding and syntax vs. semantics.- Robot reply

- Suppose that instead of a room, the program was placed into a robot that could wander around and interact with its environment. This would allow a "causal connection" between the symbols and things they represent.[67][t] Hans Moravec comments: "If we could graft a robot to a reasoning program, we wouldn't need a person to provide the meaning anymore: it would come from the physical world."[69][u]

- Searle's reply is to suppose that, unbeknownst to the individual in the Chinese room, some of the inputs came directly from a camera mounted on a robot, and some of the outputs were used to manipulate the arms and legs of the robot. Nevertheless, the person in the room is still just following the rules, and does not know what the symbols mean. Searle writes "he doesn't see what comes into the robot's eyes."[71] (See Mary's room for a similar thought experiment.)

- Derived meaning

- Some respond that the room, as Searle describes it, is connected to the world: through the Chinese speakers that it is "talking" to and through the programmers who designed the knowledge base in his file cabinet. The symbols Searle manipulates are already meaningful, they're just not meaningful to him.[72][v]

- Searle says that the symbols only have a "derived" meaning, like the meaning of words in books. The meaning of the symbols depends on the conscious understanding of the Chinese speakers and the programmers outside the room. The room, according to Searle, has no understanding of its own.[w]

- Commonsense knowledge / contextualist reply

- Some have argued that the meanings of the symbols would come from a vast "background" of commonsense knowledge encoded in the program and the filing cabinets. This would provide a "context" that would give the symbols their meaning.[70][x]

- Searle agrees that this background exists, but he does not agree that it can be built into programs. Hubert Dreyfus has also criticized the idea that the "background" can be represented symbolically.[75]

However, for those who accept that Searle's actions simulate a mind, separate from his own, the important question is not what the symbols mean to Searle, what is important is what they mean to the virtual mind. While Searle is trapped in the room, the virtual mind is not: it is connected to the outside world through the Chinese speakers it speaks to, through the programmers who gave it world knowledge, and through the cameras and other sensors that roboticists can supply.

Brain simulation and connectionist replies: redesigning the room

These arguments are all versions of the systems reply that identify a particular kind of system as being important; they identify some special technology that would create conscious understanding in a machine. (Note that the "robot" and "commonsense knowledge" replies above also specify a certain kind of system as being important.)- Brain simulator reply

- Suppose that the program simulated in fine detail the action of every neuron in the brain of a Chinese speaker.[78][z] This strengthens the intuition that there would be no significant difference between the operation of the program and the operation of a live human brain.

- Searle replies that such a simulation does not reproduce the important features of the brain—its causal and intentional states. Searle is adamant that "human mental phenomena [are] dependent on actual physical–chemical properties of actual human brains."[25] Moreover, he argues:

[I]magine that instead of a monolingual man in a room shuffling symbols we have the man operate an elaborate set of water pipes with valves connecting them. When the man receives the Chinese symbols, he looks up in the program, written in English, which valves he has to turn on and off. Each water connection corresponds to a synapse in the Chinese brain, and the whole system is rigged up so that after doing all the right firings, that is after turning on all the right faucets, the Chinese answers pop out at the output end of the series of pipes. Now where is the understanding in this system? It takes Chinese as input, it simulates the formal structure of the synapses of the Chinese brain, and it gives Chinese as output. But the man certainly doesn't understand Chinese, and neither do the water pipes, and if we are tempted to adopt what I think is the absurd view that somehow the conjunction of man and water pipes understands, remember that in principle the man can internalize the formal structure of the water pipes and do all the "neuron firings" in his imagination.[12]

- Two variations on the brain simulator reply are:

- China brain

- What if we ask each citizen of China to simulate one neuron, using the telephone system to simulate the connections between axons and dendrites? In this version, it seems obvious that no individual would have any understanding of what the brain might be saying.[80][aa]

-

- Brain replacement scenario

- In this, we are asked to imagine that engineers have invented a tiny computer that simulates the action of an individual neuron. What would happen if we replaced one neuron at a time? Replacing one would clearly do nothing to change conscious awareness. Replacing all of them would create a digital computer that simulates a brain. If Searle is right, then conscious awareness must disappear during the procedure (either gradually or all at once). Searle's critics argue that there would be no point during the procedure when he can claim that conscious awareness ends and mindless simulation begins.[82][ab] Searle predicts that, while going through the brain prosthesis, "you find, to your total amazement, that you are indeed losing control of your external behavior. You find, for example, that when doctors test your vision, you hear them say 'We are holding up a red object in front of you; please tell us what you see.' You want to cry out 'I can't see anything. I'm going totally blind.' But you hear your voice saying in a way that is completely outside of your control, 'I see a red object in front of me.' [...] [Y]our conscious experience slowly shrinks to nothing, while your externally observable behavior remains the same."[84] (See Ship of Theseus for a similar thought experiment.)

- Connectionist replies

- Closely related to the brain simulator reply, this claims that a massively parallel connectionist architecture would be capable of understanding.[ac]

- Combination reply

- This response combines the robot reply with the brain simulation reply, arguing that a brain simulation connected to the world through a robot body could have a mind.[87]

- Many mansions/Wait till next year reply

- Better technology in the future will allow computers to understand.[26][ad] Searle agrees that this is possible, but considers this point irrelevant. His argument is that a machine using a program to manipulate formally defined elements can't produce understanding. Searle's argument, if correct, rules out only this particular design. Searle agrees that there may be other designs that would cause a machine to have conscious understanding.

In the first case, where features like a robot body or a connectionist architecture are required, Searle claims that strong AI (as he understands it) has been abandoned.[ae] The Chinese room has all the elements of a Turing complete machine, and thus is capable of simulating any digital computation whatsoever. If Searle's room can't pass the Turing test then there is no other digital technology that could pass the Turing test. If Searle's room could pass the Turing test, but still does not have a mind, then the Turing test is not sufficient to determine if the room has a "mind". Either way, it denies one or the other of the positions Searle thinks of as "strong AI", proving his argument.

The brain arguments in particular deny strong AI if they assume that there is no simpler way to describe the mind than to create a program that is just as mysterious as the brain was. He writes "I thought the whole idea of strong AI was that we don't need to know how the brain works to know how the mind works."[26] If computation does not provide an explanation of the human mind, then strong AI has failed, according to Searle.

Other critics hold that the room as Searle described it does, in fact, have a mind, however they argue that it is difficult to see—Searle's description is correct, but misleading. By redesigning the room more realistically they hope to make this more obvious. In this case, these arguments are being used as appeals to intuition (see next section).

In fact, the room can just as easily be redesigned to weaken our intuitions. Ned Block's Blockhead argument[88] suggests that the program could, in theory, be rewritten into a simple lookup table of rules of the form "if the user writes S, reply with P and goto X". At least in principle, any program can be rewritten (or "refactored") into this form, even a brain simulation.[af] In the blockhead scenario, the entire mental state is hidden in the letter X, which represents a memory address—a number associated with the next rule. It is hard to visualize that an instant of one's conscious experience can be captured in a single large number, yet this is exactly what "strong AI" claims. On the other hand, such a lookup table would be ridiculously large (to the point of being physically impossible), and the states could therefore be extremely specific.

Searle argues that however the program is written or however the machine is connected to the world, the mind is being simulated by a simple step by step digital machine (or machines). These machines are always just like the man in the room: they understand nothing and don't speak Chinese. They are merely manipulating symbols without knowing what they mean. Searle writes: "I can have any formal program you like, but I still understand nothing."[9]

Speed and complexity: appeals to intuition

The following arguments (and the intuitive interpretations of the arguments above) do not directly explain how a Chinese speaking mind could exist in Searle's room, or how the symbols he manipulates could become meaningful. However, by raising doubts about Searle's intuitions they support other positions, such as the system and robot replies. These arguments, if accepted, prevent Searle from claiming that his conclusion is obvious by undermining the intuitions that his certainty requires.Several critics believe that Searle's argument relies entirely on intuitions. Ned Block writes "Searle's argument depends for its force on intuitions that certain entities do not think."[89] Daniel Dennett describes the Chinese room argument as a misleading "intuition pump"[90] and writes "Searle's thought experiment depends, illicitly, on your imagining too simple a case, an irrelevant case, and drawing the 'obvious' conclusion from it."[90]

Some of the arguments above also function as appeals to intuition, especially those that are intended to make it seem more plausible that the Chinese room contains a mind, which can include the robot, commonsense knowledge, brain simulation and connectionist replies. Several of the replies above also address the specific issue of complexity. The connectionist reply emphasizes that a working artificial intelligence system would have to be as complex and as interconnected as the human brain. The commonsense knowledge reply emphasizes that any program that passed a Turing test would have to be "an extraordinarily supple, sophisticated, and multilayered system, brimming with 'world knowledge' and meta-knowledge and meta-meta-knowledge", as Daniel Dennett explains.[74]

- Speed and complexity replies

- The speed at which human brains process information is (by some estimates) 100 billion operations per second.[91] Several critics point out that the man in the room would probably take millions of years to respond to a simple question, and would require "filing cabinets" of astronomical proportions. This brings the clarity of Searle's intuition into doubt.[92][ag]

- Churchland's luminous room

- "Consider a dark room containing a man holding a bar magnet or charged object. If the man pumps the magnet up and down, then, according to Maxwell's theory of artificial luminance (AL), it will initiate a spreading circle of electromagnetic waves and will thus be luminous. But as all of us who have toyed with magnets or charged balls well know, their forces (or any other forces for that matter), even when set in motion produce no luminance at all. It is inconceivable that you might constitute real luminance just by moving forces around!"[81] The problem is that he would have to wave the magnet up and down something like 450 trillion times per second in order to see anything.[94]

Searle argues that his critics are also relying on intuitions, however his opponents' intuitions have no empirical basis. He writes that, in order to consider the "system reply" as remotely plausible, a person must be "under the grip of an ideology".[28] The system reply only makes sense (to Searle) if one assumes that any "system" can have consciousness, just by virtue of being a system with the right behavior and functional parts. This assumption, he argues, is not tenable given our experience of consciousness.

Other minds and zombies: meaninglessness

Several replies argue that Searle's argument is irrelevant because his assumptions about the mind and consciousness are faulty. Searle believes that human beings directly experience their consciousness, intentionality and the nature of the mind every day, and that this experience of consciousness is not open to question. He writes that we must "presuppose the reality and knowability of the mental."[98] These replies question whether Searle is justified in using his own experience of consciousness to determine that it is more than mechanical symbol processing. In particular, the other minds reply argues that we cannot use our experience of consciousness to answer questions about other minds (even the mind of a computer), and the epiphenomena reply argues that Searle's consciousness does not "exist" in the sense that Searle thinks it does.- Other minds reply

- This reply points out that Searle's argument is a version of the problem of other minds, applied to machines. There is no way we can determine if other people's subjective experience is the same as our own. We can only study their behavior (i.e., by giving them our own Turing test). Critics of Searle argue that he is holding the Chinese room to a higher standard than we would hold an ordinary person.[99][ai]

Alan Turing anticipated Searle's line of argument (which he called "The Argument from Consciousness") in 1950 and makes the other minds reply.[102] He noted that people never consider the problem of other minds when dealing with each other. He writes that "instead of arguing continually over this point it is usual to have the polite convention that everyone thinks."[103] The Turing test simply extends this "polite convention" to machines. He doesn't intend to solve the problem of other minds (for machines or people) and he doesn't think we need to.[aj]

- Epiphenomenon / zombie reply

- Several philosophers argue that consciousness, as Searle describes it, does not exist. This position is sometimes referred to as eliminative materialism: the view that consciousness is a property that can be reduced to a strictly mechanical description, and that our experience of consciousness is, as Daniel Dennett describes it, a "user illusion".[106]

- Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig argue that, if we accept Searle's description of intentionality, consciousness and the mind, we are forced to accept that consciousness is epiphenomenal: that it "casts no shadow", that it is undetectable in the outside world. They argue that Searle must be mistaken about the "knowability of the mental", and in his belief that there are "causal properties" in our neurons that give rise to the mind. They point out that, by Searle's own description, these causal properties can't be detected by anyone outside the mind, otherwise the Chinese Room couldn't pass the Turing test—the people outside would be able to tell there wasn't a Chinese speaker in the room by detecting their causal properties. Since they can't detect causal properties, they can't detect the existence of the mental. In short, Searle's "causal properties" and consciousness itself is undetectable, and anything that cannot be detected either does not exist or does not matter.[107]

- Dennett's reply from natural selection

- Suppose that, by some mutation, a human being is born that does not have Searle's "causal properties" but nevertheless acts exactly like a human being. (This sort of animal is called a "zombie" in thought experiments in the philosophy of mind). This new animal would reproduce just as any other human and eventually there would be more of these zombies. Natural selection would favor the zombies, since their design is (we could suppose) a bit simpler. Eventually the humans would die out. So therefore, if Searle is right, it is most likely that human beings (as we see them today) are actually "zombies", who nevertheless insist they are conscious. It is impossible to know whether we are all zombies or not. Even if we are all zombies, we would still believe that we are not.[108]

- Newton's flaming laser sword reply

- Mike Alder argues that the entire argument is frivolous, because it is non-positivist: not only is the distinction between simulating a mind and having a mind ill-defined, but it is also irrelevant because no experiments were, or even can be, proposed to distinguish between the two.[109]

In popular culture

The Chinese room argument is a central concept in Peter Watts's novels Blindsight and (to a lesser extent) Echopraxia. It is also a central theme in the video game Virtue's Last Reward, and ties into the game's narrative. In Season 4 of the American crime drama Numb3rs there is a brief reference to the Chinese room.[citation needed]The Chinese Room is also the name of a British independent video game development studio best known for working on experimental first-person games, such as Everybody's Gone to the Rapture, or Dear Esther.[citation needed][110]