The causes and mechanisms of the fall of the Western Roman Empire are a historical theme that was introduced by historian Edward Gibbon in his 1776 book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. He started an ongoing historiographical discussion about what caused the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, and the reduced power of the remaining Eastern Empire, in the 4th–5th centuries. Gibbon was not the first to speculate on why the Empire collapsed, but he was the first to give a well-researched and well-referenced account. Many theories of causality have been explored. In 1984, Alexander Demandt enumerated 210 different theories on why Rome fell, and new theories emerged thereafter. Gibbon himself explored ideas of internal decline (the disintegration of political, economic, military, and other social institutions, civil wars) and of attacks from outside the Empire. "From the eighteenth century onward," historian Glen Bowersock wrote, "we have been obsessed with the fall: it has been valued as an archetype for every perceived decline, and, hence, as a symbol for our own fears."

Overview of historiography

Historiographically, the primary issue historians have looked at when analyzing any theory is the continued existence of the Eastern Empire or Byzantine Empire, which lasted almost a thousand years after the fall of the West. For example, Gibbon implicates Christianity in the fall of the Western Empire, yet the eastern half of the Empire, which was even more Christian than the west in geographic extent, fervor, penetration and vast numbers continued on for a thousand years afterwards (although Gibbon did not consider the Eastern Empire to be much of a success). As another example, environmental or weather changes affected the east as much as the west, yet the east did not "fall."

Theories will sometimes reflect the particular concerns that historians might have on cultural, political, or economic trends in their own times. Gibbon's criticism of Christianity reflects the values of the Enlightenment; his ideas on the decline in martial vigor could have been interpreted by some as a warning to the growing British Empire. In the 19th century socialist and anti-socialist theorists tended to blame decadence and other political problems. More recently, environmental concerns have become popular, with deforestation and soil erosion proposed as major factors, and destabilizing population decreases due to epidemics such as early cases of bubonic plague and malaria also cited. Global climate changes of 535–536, perhaps caused by the possible eruption of Krakatoa in 535, as mentioned by David Keys and others, is another example. Ideas about transformation with no distinct fall mirror the rise of the postmodern tradition, which rejects periodization concepts. What is not new are attempts to diagnose Rome's particular problems, with Satire X, written by Juvenal in the early 2nd century at the height of Roman power, criticizing the peoples' obsession with "bread and circuses" and rulers seeking only to gratify these obsessions.

One of the primary reasons for the vast number of theories is the notable lack of surviving evidence from the 4th and 5th centuries. For example, there are so few records of an economic nature it is difficult to arrive at even a generalization of the economic conditions. Thus, historians must quickly depart from available evidence and comment based on how things ought to have worked, or based on evidence from previous and later periods, on inductive reasoning. As in any field where available evidence is sparse, the historian's ability to imagine the 4th and 5th centuries will play as important a part in shaping our understanding as the available evidence, and thus be open for endless interpretation.

The end of the Western Roman Empire traditionally has been seen by historians to mark the end of the Ancient Era and beginning of the Middle Ages. More recent schools of history, such as Late Antiquity, offer a more nuanced view from the traditional historical narrative.

There is no consensus on a date for the start of the Decline. Gibbon started his account in 98. The year 376 is taken as pivotal by many modern historians. In that year there was an unmanageable influx of Goths and other Barbarians into the Balkan provinces, and the situation of the Western Empire generally worsened thereafter, with recoveries being incomplete and temporary. Significant events include the Battle of Adrianople in 378, the death of Theodosius I in 395 (the last time the Roman Empire was politically unified), the crossing of the Rhine in 406 by Germanic tribes, the execution of Stilicho in 408, the sack of Rome in 410, the death of Constantius III in 421, the death of Aetius in 454, and the second sack of Rome in 455, with the death of Majorian in 461 marking the end of the last opportunity for recovery.

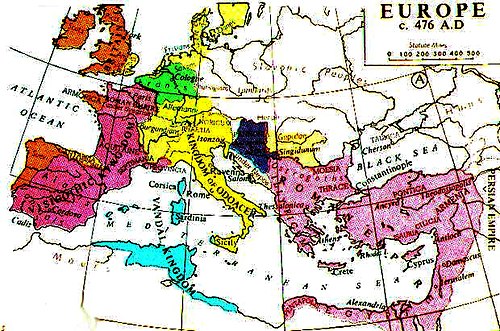

Gibbon took September 4, 476 as a convenient marker for the final dissolution of the Western Roman Empire, when Romulus Augustus, the last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed by Odoacer, a Germanic chieftain. Some modern historians question the significance of the year 476 for its end. Julius Nepos, the Western emperor recognized by the Eastern Roman Empire, continued to rule in Dalmatia, until he was assassinated in 480. The Ostrogothic rulers of Italia considered themselves upholders of the direct line of Roman tradition, and the Eastern emperors considered themselves the sole rightful Roman rulers of a united empire. Roman cultural traditions continued throughout the territory of the Western Empire, and a recent school of interpretation argues that the great political changes can more accurately be described as a complex cultural transformation, rather than a fall.

Overview of events

The decline of the Roman Empire is one of the traditional markers of the end of Classical Antiquity and the beginning of the European Middle Ages. Throughout the 5th century, the Empire's territories in western Europe and northwestern Africa, including Italy, fell to various invading or indigenous peoples in what is sometimes called the Migration period. Although the eastern half still survived with borders essentially intact for several centuries (until the Muslim conquests), the Empire as a whole had initiated major cultural and political transformations since the Crisis of the Third Century, with the shift towards a more openly autocratic and ritualized form of government, the adoption of Christianity as the state religion, and a general rejection of the traditions and values of Classical Antiquity. While traditional historiography emphasized this break with Antiquity by using the term "Byzantine Empire" instead of Roman Empire, recent schools of history offer a more nuanced view, seeing mostly continuity rather than a sharp break. The Empire of Late Antiquity already looked very different from classical Rome.

The Roman Empire emerged from the Roman Republic when Julius Caesar and Augustus Caesar transformed it from a republic into a monarchy. Rome reached its zenith in the 2nd century, then fortunes slowly declined (with many revivals and restorations along the way). The reasons for the decline of the Empire are still debated today, and are likely multiple. Historians infer that the population appears to have diminished in many provinces—especially western Europe—from the diminishing size of fortifications built to protect the cities from barbarian incursions from the 3rd century on. Some historians even have suggested that parts of the periphery were no longer inhabited because these fortifications were restricted to the center of the city only. Tree rings suggest "distinct drying" beginning in 250.

By the late 3rd century, the city of Rome no longer served as an effective capital for the Emperor and various cities were used as new administrative capitals. Successive emperors, starting with Constantine, privileged the eastern city of Byzantium, which he had entirely rebuilt after a siege. Later renamed Constantinople, and protected by formidable walls in the late 4th and early 5th centuries, it was to become the largest and most powerful city of Christian Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Since the Crisis of the Third Century, the Empire was intermittently ruled by more than one emperor at once (usually two), presiding over different regions. At first a haphazard form of power sharing, this eventually settled on an east–west administrative division between the Western Roman Empire (centered on Rome, but now usually presided from other seats of power such as Trier, Milan, and especially Ravenna), and the Eastern Roman Empire (with its capital initially in Nicomedia, and later Constantinople). The Latin-speaking west, under dreadful demographic crisis, and the wealthier Greek-speaking east, also began to diverge politically and culturally. Although this was a gradual process, still incomplete when Italy came under the rule of barbarian chieftains in the last quarter of the 5th century, it deepened further afterward, and had lasting consequences for the medieval history of Europe.

Throughout the 5th century, Western emperors were usually figureheads, while the Eastern emperors maintained more independence. For most of the time, the actual rulers in the West were military strongmen who took the titles of magister militum, patrician, or both, such as Stilicho, Aetius, and Ricimer. Although Rome was no longer the capital in the West, it remained the West's largest city and its economic center. But the city was sacked by rebellious Visigoths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455, events that shocked contemporaries and signaled the disintegration of Roman authority. Saint Augustine wrote The City of God partly as an answer to critics who blamed the sack of Rome by the Visigoths on the abandonment of the traditional pagan religions.

In June 474, Julius Nepos became Western Emperor but in the next year the magister militum Orestes revolted and made his son Romulus Augustus emperor. Romulus, however, was not recognized by the Eastern Emperor Zeno and so was technically an usurper, Nepos still being the legal Western Emperor. Nevertheless, Romulus Augustus is often known as the last Western Roman Emperor. In 476, after being refused lands in Italy, Orestes' Germanic mercenaries under the leadership of the chieftain Odoacer captured and executed Orestes and took Ravenna, the Western Roman capital at the time, deposing Romulus Augustus. The whole of Italy was quickly conquered, and Odoacer was granted the title of patrician by Zeno, effectively recognizing his rule in the name of the Eastern Empire. Odoacer returned the Imperial insignia to Constantinople and ruled as King in Italy. Following Nepos' death Theodoric the Great, King of the Ostrogoths, conquered Italy with Zeno's approval.

Meanwhile, much of the rest of the Western provinces were conquered by waves of Germanic invasions, most of them being disconnected politically from the East altogether and continuing a slow decline. Although Roman political authority in the West was lost, Roman culture would last in most parts of the former Western provinces into the 6th century and beyond.

The first invasions disrupted the West to some degree, but it was the Gothic War launched by the Eastern Emperor Justinian in the 6th century, and meant to reunite the Empire, that eventually caused the most damage to Italy, as well as straining the Eastern Empire militarily. Following these wars, Rome and other Italian cities would fall into severe decline (Rome itself was almost completely abandoned). Another blow came with the Persian invasion of the East in the 7th century, immediately followed by the Muslim conquests, especially of Egypt, which curtailed much of the key trade in the Mediterranean on which Europe depended.

The Empire was to live on in the East for many centuries, and enjoy periods of recovery and cultural brilliance, but its size would remain a fraction of what it had been in classical times. It became an essentially regional power, centered on Greece and Anatolia. Modern historians tend to prefer the term Byzantine Empire for the eastern, medieval stage of the Roman Empire.

Highlights

The decline of the Western Roman Empire was a process spanning many centuries; there is no consensus when it might have begun but many dates and time lines have been proposed by historians.

- 3rd century

- The Crisis of the Third Century (234–284), a period of political instability.

- The reign of Emperor Diocletian (284–305), who attempted substantial political and economic reforms, many of which would remain in force in the following centuries.

- 4th century

- The reign of Constantine I (306–337), who built the new eastern capital of Constantinople and converted to Christianity, legalizing and even favoring to some extent this religion. All Roman emperors after Constantine, except for Julian, would be Christians.

- The first war with the Visigoths (376–382), culminating in the Battle of Adrianople (August 9, 378), in which a large Roman army was defeated by the Visigoths, and Emperor Valens was killed. The Visigoths, fleeing a migration of the Huns, had been allowed to settle within the borders of the Empire by Valens, but were mistreated by the local Roman administrators, and rebelled.

- The reign of Theodosius I (379–395), last emperor to reunite under his authority the western and eastern halves of the Empire. Theodosius continued and intensified the policies against paganism of his predecessors, eventually outlawing it, and making Nicaean Christianity the state religion.

- 5th century

- The Crossing of the Rhine: on December 31, 406 (or 405, according to some historians), a mixed band of Vandals, Suebi and Alans crossed the frozen river Rhine at Moguntiacum (modern Mainz), and began to ravage Gaul. Some moved on to the regions of Hispania and Africa. The Empire would never regain control over most of these lands.

- The second war with the Visigoths, led by king Alaric, in which they raided Greece, and then invaded Italy, culminating in the sack of Rome (410). The Visigoths eventually left Italy and founded the Visigothic Kingdom in southern Gaul and Hispania.

- The rise of the Hunnic Empire under Attila and Bleda (434–453), who raided the Balkans, Gaul, and Italy, threatening both Constantinople and Rome.

- The second sack of Rome, this time by the Vandals (455).

- Failed counterstrikes against the Vandals (461–468). The Western Emperor Majorian planned a naval campaign against the Vandals to reconquer northern Africa in 461, but word of the preparations got out to the Vandals, who took the Roman fleet by surprise and destroyed it. A second naval expedition against the Vandals, sent by Emperors Leo I and Anthemius, was defeated at Cape Bon in 468.

- Deposition of the last Western Emperors, Julius Nepos and Romulus Augustus (475–480). Julius Nepos, who had been nominated by the Eastern Emperor Zeno, was deposed by the rebelled magister militum Orestes, who installed his own son Romulus in the imperial throne. Both Zeno and his rival Basiliscus, in the East, continued to regard Julius Nepos, who fled to Dalmatia, as the legitimate Western Emperor, and Romulus as an usurper. Shortly after, Odoacer, magister militum appointed by Julius, invaded Italy, defeated Orestes, and deposed Romulus Augustus on September 4, 476. Odoacer then proclaimed himself ruler of Italy and asked the Eastern Emperor Zeno to become formal Emperor of both empires, and in so doing legalize Odoacer's own position as Imperial viceroy of Italy. Zeno did so, setting aside the claims of Nepos, who was murdered by his own soldiers in 480.

- Foundation of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy (493). Concerned with the success and popularity of Odoacer, Zeno started a campaign against him, at first with words, then by inciting the Ostrogoths to take back Italy from him. They did as much, but then founded an independent kingdom of their own, under the rule of king Theodoric. Italy and the entire West were lost to the Empire.

Theories and explanations of a fall

The various theories and explanations for the fall of the Roman Empire in the West may be very broadly classified into four schools of thought, although the classification is not without overlap:

The tradition positing general malaise goes back to Edward Gibbon who argued that the edifice of the Roman Empire had been built on unsound foundations to begin with. According to Gibbon, the fall was - in the final analysis - inevitable. On the other hand, Gibbon had assigned a major portion of the responsibility for the decay to the influence of Christianity, and is often, though perhaps unjustly, seen as the founding father of the school of monocausal explanation.

On the other hand, the school of catastrophic collapse holds that the fall of the Empire had not been a pre-determined event and need not be taken for granted. Rather, it was due to the combined effect of a number of adverse processes, many of them set in motion by the Migration of the Peoples, that together applied too much stress to the Empire's basically sound structure.

Finally, the transformation school challenges the whole notion of the 'fall' of the Empire, asking to distinguish between the fall into disuse of a particular political dispensation, anyway unworkable towards its end, and the fate of the Roman civilisation which under-girded the Empire. According to this school, drawing its basic premise from the Pirenne thesis, the Roman world underwent a gradual (though often violent) series of transformations, morphing into the medieval world. The historians belonging to this school often prefer to speak of Late Antiquity instead of the Fall of the Roman Empire.

Decay owing to general malaise

Edward Gibbon

In The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), Edward Gibbon famously placed the blame on a loss of civic virtue among the Roman citizens. They gradually entrusted the role of defending the Empire to barbarian mercenaries who eventually turned on them. Gibbon held that Christianity contributed to this shift by making the populace less interested in the worldly here-and-now because it was willing to wait for the rewards of heaven.

The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight.

In discussing Barbarism and Christianity I have actually been discussing the Fall of Rome.

Vegetius on military decline

Writing in the 5th century, the Roman historian Vegetius pleaded for reform of what must have been a greatly weakened army. The historian Arther Ferrill has suggested that the Roman Empire – particularly the military – declined largely as a result of an influx of Germanic mercenaries into the ranks of the legions. This "Germanization" and the resultant cultural dilution or "barbarization" led not only to a decline in the standard of drill and overall military preparedness within the Empire, but also to a decline of loyalty to the Roman government in favor of loyalty to commanders. Ferrill agrees with other Roman historians such as A.H.M. Jones:

...the decay of trade and industry was not a cause of Rome’s fall. There was a decline in agriculture and land was withdrawn from cultivation, in some cases on a very large scale, sometimes as a direct result of barbarian invasions. However, the chief cause of the agricultural decline was high taxation on the marginal land, driving it out of cultivation. Jones is surely right in saying that taxation was spurred by the huge military budget and was thus ‘indirectly’ the result of the barbarian invasion.

Arnold J. Toynbee and James Burke

In contrast with the declining empire theories, historians such as Arnold J. Toynbee and James Burke argue that the Roman Empire itself was a rotten system from its inception, and that the entire Imperial era was one of steady decay of institutions founded in Republican times. In their view, the Empire could never have lasted longer than it did without radical reforms that no Emperor could implement. The Romans had no budgetary system and thus wasted whatever resources they had available. The economy of the Empire was a Raubwirtschaft or plunder economy based on looting existing resources rather than producing anything new. The Empire relied on riches from conquered territories (this source of revenue ending, of course, with the end of Roman territorial expansion) or on a pattern of tax collection that drove small-scale farmers into destitution (and onto a dole that required even more exactions upon those who could not escape taxation), or into dependency upon a landed élite exempt from taxation. With the cessation of tribute from conquered territories, the full cost of their military machine had to be borne by the citizenry.

An economy based upon slave labor precluded a middle class with buying power. The Roman Empire produced few exportable goods. Material innovation, whether through entrepreneurialism or technological advancement, all but ended long before the final dissolution of the Empire. Meanwhile, the costs of military defense and the pomp of Emperors continued. Financial needs continued to increase, but the means of meeting them steadily eroded. In the end, due to economic failure, even the armor and weaponry of soldiers became so obsolete that the enemies of the Empire had better armor and weapons as well as larger forces. The decrepit social order offered so little to its subjects that many saw the barbarian invasion as liberation from onerous obligations to the ruling class.

By the late 5th century the barbarian conqueror Odoacer had no use for the formality of an Empire upon deposing Romulus Augustus and chose neither to assume the title of Emperor himself nor to select a puppet, although legally he kept the lands as a commander of the Eastern Empire and maintained the Roman institutions such as the consulship. The formal end of the Roman Empire on the West in AD 476 thus corresponds with the time in which the Empire and the title Emperor no longer had value.

Michael Rostovtzeff, Ludwig von Mises, and Bruce Bartlett

Historian Michael Rostovtzeff and economist Ludwig von Mises both argued that unsound economic policies played a key role in the impoverishment and decay of the Roman Empire. According to them, by the 2nd century AD, the Roman Empire had developed a complex market economy in which trade was relatively free. Tariffs were low and laws controlling the prices of foodstuffs and other commodities had little impact because they did not fix the prices significantly below their market levels. After the 3rd century, however, debasement of the currency (i.e., the minting of coins with diminishing content of gold, silver, and bronze) led to inflation. The price control laws then resulted in prices that were significantly below their free-market equilibrium levels. It should, however, be noted that Constantine initiated a successful reform of the currency which was completed before the barbarian invasions of the 4th century, and that thereafter the currency remained sound everywhere that remained within the empire until at least the 11th century - at any rate for gold coins.

According to Rostovtzeff and Mises, artificially low prices led to the scarcity of foodstuffs, particularly in cities, whose inhabitants depended on trade to obtain them. Despite laws passed to prevent migration from the cities to the countryside, urban areas gradually became depopulated and many Roman citizens abandoned their specialized trades to practice subsistence agriculture. This, coupled with increasingly oppressive and arbitrary taxation, led to a severe net decrease in trade, technical innovation, and the overall wealth of the Empire.

Bruce Bartlett traces the beginning of debasement to the reign of Nero. He claims that the emperors increasingly relied on the army as the sole source of their power, and therefore their economic policy was driven more and more by a desire to increase military funding in order to buy the army's loyalty. By the 3rd century, according to Bartlett, the monetary economy had collapsed. But the imperial government was now in a position where it had to satisfy the demands of the army at all costs. Failure to do so would result in the army forcibly deposing the emperor and installing a new one. Therefore, being unable to increase monetary taxes, the Roman Empire had to resort to direct requisitioning of physical goods anywhere it could find them - for example taking food and cattle from farmers. The result, in Bartlett's view, was social chaos, and this led to different responses from the authorities and from the common people. The authorities tried to restore order by requiring free people (i.e. non-slaves) to remain in the same occupation or even at the same place of employment. Eventually, this practice was extended to force children to follow the same occupation as their parents. So, for instance, farmers were tied to the land, and the sons of soldiers had to become soldiers themselves. Many common people reacted by moving to the countryside, sometimes joining the estates of the wealthy, and in general trying to be self-sufficient and interact as little as possible with the imperial authorities. Thus, according to Bartlett, Roman society began to dissolve into a number of separate estates that operated as closed systems, provided for all their own needs and did not engage in trade at all. These were the beginnings of feudalism.

Joseph Tainter

In his 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies, American anthropologist Tainter presents the view that for given technological levels there are implicit declining returns to complexity, in which systems deplete their resource base beyond levels that are ultimately sustainable. Tainter argues that societies become more complex as they try to solve problems. Social complexity can include differentiated social and economic roles, reliance on symbolic and abstract communication, and the existence of a class of information producers and analysts who are not involved in primary resource production. Such complexity requires a substantial "energy" subsidy (meaning resources, or other forms of wealth). When a society confronts a "problem", such as a shortage of or difficulty in gaining access to energy, it tends to create new layers of bureaucracy, infrastructure, or social class to address the challenge.

For example, as Roman agricultural output slowly declined and population increased, per-capita energy availability dropped. The Romans solved this problem in the short term by conquering their neighbours to appropriate their energy surpluses (metals, grain, slaves, etc.). However, this solution merely exacerbated the issue over the long term; as the Empire grew, the cost of maintaining communications, garrisons, civil government, etc., increased. Eventually, this cost grew so great that any new challenges such as invasions and crop failures could not be solved by the acquisition of more territory. At that point, the Empire fragmented into smaller units.

Though it's often presumed that the collapse of the Roman Empire was a catastrophe for everyone involved, Tainter points out that it can be seen as a very rational preference of individuals at the time, many of whom were better off (all but the elite, presumably). Archeological evidence from human bones indicates that average nutrition improved after the collapse in many parts of the former Roman Empire. Average individuals may have benefited because they no longer had to invest in the burdensome complexity of empire.

In Tainter's view, while invasions, crop failures, disease or environmental degradation may be the apparent causes of societal collapse, the ultimate cause is diminishing returns on investments in social complexity.

Adrian Goldsworthy

In The Complete Roman Army (2003) Adrian Goldsworthy, a British military historian, sees the causes of the collapse of the Roman Empire not in any 'decadence' in the make-up of the Roman legions, but in a combination of endless civil wars between factions of the Roman Army fighting for control of the Empire. This inevitably weakened the army and the society upon which it depended, making it less able to defend itself against the growing numbers of Rome's enemies. The army still remained a superior fighting instrument to its opponents, both civilized and barbarian; this is shown in the victories over Germanic tribes at the Battle of Strasbourg (357) and in its ability to hold the line against the Sassanid Persians throughout the 4th century. But, says Goldsworthy, "Weakening central authority, social and economic problems and, most of all, the continuing grind of civil wars eroded the political capacity to maintain the army at this level." Goldsworthy set out in greater detail his theory that recurring civil wars during the late fourth and early fifth centuries contributed to the fall of the West Roman Empire (395-476), in his book The Fall of the West: The Slow Death of the Roman Superpower (2009).

Monocausal decay

Disease

William H. McNeill, a world historian, noted in chapter three of his book Plagues and Peoples (1976) that the Roman Empire suffered the severe and protracted Antonine Plague starting around 165 AD. For about twenty years, waves of one or more diseases, possibly the first epidemics of smallpox and measles, swept through the Empire, ultimately killing about half the population. Similar epidemics, such as the Plague of Cyprian, also occurred in the 3rd century. McNeill argues that the severe fall in population left the state apparatus and army too large for the population to support, leading to further economic and social decline that eventually killed the Western Empire. The Eastern half survived due to its larger population, which even after the plagues was sufficient for an effective state apparatus.

Archaeology has revealed that from the 2nd century onward, the inhabited area in most Roman towns and cities grew smaller and smaller. Imperial laws concerning "agri deserti", or deserted lands, became increasingly common and desperate. The economic collapse of the 3rd century may also be evidence of a shrinking population as Rome's tax base was also shrinking and could no longer support the Roman Army and other Roman institutions.

Rome's success had led to increased contact with Asia though trade, especially in a sea route through the Red Sea that Rome cleared of pirates shortly after conquering Egypt. Wars also increased contact with Asia, particularly wars with the Persian Empire. With increased contact with Asia came increased transmission of disease into the Mediterranean from Asia. Romans used public fountains, public latrines, public baths, and supported many brothels all of which were conducive to the spread of pathogens. Romans crowded into walled cities and the poor and the slaves lived in very close quarters with each other. Epidemics began sweeping though the Empire.

The culture of the German barbarians living just across the Rhine and Danube rivers was not so conducive to the spread of pathogens. Germans lived in small scattered villages that did not support the same level of trade as did Roman settlements. Germans lived in single-family detached houses. Germans did not have public baths nor as many brothels and drank ale made with boiled water. The barbarian population seemed to be on the rise. The demographics of Europe were changing.

Economically, depopulation led to the impoverishment of East and West as economic ties among different parts of the empire weakened. Increasing raids by barbarians further strained the economy and further reduced the population, mostly in the West. In areas near the Rhine and Danube frontiers, raids by barbarians killed Romans and disrupted commerce. Raids also forced Romans into walled towns and cities furthering the spread of pathogens and increasing the rate of depopulation in the West. A low population and weak economy forced Rome to use barbarians in the Roman Army to defend against other barbarians.

Environmental degradation

Another theory is that gradual environmental degradation caused population and economic decline. Deforestation and excessive grazing led to erosion of meadows and cropland. Increased irrigation without suitable drainage caused salinization, especially in North Africa. These human activities resulted in fertile land becoming nonproductive and eventually increased desertification in some regions. Many animal species became extinct. The recent research of Tainter stated that "deforestation did not cause the Roman collapse", although it could be a minor contributing factor.

Also, high taxes and heavy slavery are another reason for decline, as they forced small farmers out of business and into the cities, which became overpopulated. Roman cities were only designed to hold a certain number of people, and once they passed that, disease, water shortage and food shortage became common.

Lead poisoning

Publishing several articles in the 1960s, the sociologist Seabury Colum Gilfillan advanced the argument that lead poisoning was a significant factor in the decline of the Roman Empire. Later, a posthumously published book elaborated on Gilfillan's work on this topic.

Jerome Nriagu, a geochemist, argued in a 1983 book that "lead poisoning contributed to the decline of the Roman empire." His work centred on the level to which the ancient Romans, who had few sweeteners besides honey, would boil must in lead pots to produce a reduced sugar syrup called defrutum, concentrated again into sapa. This syrup was used to some degree to sweeten wine and food. If acidic must is boiled within lead vessels the sweet syrup it yields will contain a quantity of Pb(C2H3O2)2 or lead(II) acetate. Lead was also leached from the glazes on amphorae and other pottery, from pewter drinking vessels and cookware, and from lead piping used for municipal water supplies and baths.

The main culinary use of defrutum was to sweeten wine, but it was also added to fruit and meat dishes as a sweetening and souring agent and even given to food animals such as suckling pig and duck to improve the taste of their flesh. Defrutum was mixed with garum to make the popular condiment oenogarum, and as such was one of Rome's most popular condiments. Quince and melon were preserved in defrutum and honey through the winter, and some Roman women used defrutum or sapa as a cosmetic. Defrutum was often used as a food preservative in provisions for Roman troops.

Nriagu produced a table showing his estimated consumption of lead by various classes within the Roman Empire. However, to produce the table Nriagu assumes all of the defrutum/sapa consumed to have been made in lead vessels:

| Population | Source | Lead level in source | Daily intake | Absorption factor | Lead absorbed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aristocrats | |||||

| Air | 0.05 µg/m3 | 20 m3 | 0.4 | 0.4 µg/day | |

| Water | 50 (50–200) µg/l | 1.0 liter | 0.1 | 5 (5–20) µg/day | |

| Wines | 300 (200–1500) | 2.0 liters | 0.3 | 180 (120–900) µg/day | |

| Foods | 0.2 (0.1–2.0) µg/g | 3 kg (7 lb) | 0.1 | 60 (30–600) µg/day | |

| Other/Misc. |

|

5.0 µg/day | |||

| Total |

|

250 (160-1250) µg/day | |||

| Plebeians | |||||

|

|

Less food, same wine consumption. | 35 (35-320) µg/day | |||

| Slaves | |||||

|

|

Still less food, more water, 0.75 liters wine | 15 (15-77) µg/day | |||

Lead is not removed quickly from the body. It tends to form lead phosphate complexes within bone. This is detectable in preserved bone. Chemical analysis of preserved skeletons found in Herculaneum by Dr. Sara C. Bisel from the University of Minnesota indicated they contained lead in concentrations of 84 parts per million (ppm), whereas skeletons found in a Greek cave had lead concentrations of just 3ppm. However, the lead content revealed in many other ancient Roman remains have been shown to have been less than half those of modern Europeans, which have concentrations between 20-50ppm.

Criticism of lead poisoning theory

The role and importance of lead poisoning in contributing to the fall of the Roman Empire is the subject of controversy, and its importance and validity is discounted by many historians. John Scarborough, a pharmacologist and classicist, criticized Nriagu's book as "so full of false evidence, miscitations, typographical errors, and a blatant flippancy regarding primary sources that the reader cannot trust the basic arguments." He concluded that ancient authorities were well aware of lead poisoning and that it was not endemic in the Roman empire nor did it cause its fall.

Although defrutum and sapa prepared in leaden containers would indubitably have contained toxic levels of lead, the use of leaden containers, though popular, was not the standard, and copper was used far more generally. The exact amount of sapa added to wine was also not standardised, and there is no indication of how often sapa was added or in what quantity.

Additionally, Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius recognised the toxicity of lead. Vitruvius, who flourished during Augustus' time, writes that the Romans knew very well of the dangers.

Water conducted through earthen pipes is more wholesome than that through lead; indeed that conveyed in lead must be injurious, because from it white lead [cerussa, lead carbonate, PbCO3] is obtained, and this is said to be injurious to the human system. This may be verified by observing the workers in lead, who are of a pallid colour; water should therefore on no account be conducted in leaden pipes if we are desirous that it should be wholesome.

— VIII.6.10–11

Nevertheless, recent research supports the idea that the lead found in the water came from the supply pipes, rather than another source of contamination. It was not unknown for locals to punch holes in the pipes to draw water off, increasing the number of people exposed to the lead.

Thirty years ago, Jerome Nriagu argued in a milestone paper that Roman civilization collapsed as a result of lead poisoning. Clair Patterson, the scientist who convinced governments to ban lead from gasoline, enthusiastically endorsed this idea, which nevertheless triggered a volley of publications aimed at refuting it. Although today lead is no longer seen as the prime culprit of Rome's demise, its status in the system of water distribution by lead pipes (fistulæ) still stands as a major public health issue. By measuring Pb isotope compositions of sediments from the Tiber River and the Trajanic Harbor, the present work shows that "tap water" from ancient Rome had 100 times more lead than local spring waters.

Catastrophic collapse

J. B. Bury

J. B. Bury's History of the Later Roman Empire (1889/1923) challenged the prevailing "theory of moral decay" established by Gibbon as well as the classic "clash of Christianity vs. paganism" theory, citing the relative success of the Eastern Empire, which was resolutely Christian. He held that Gibbon's grand history, though epoch-making in its research and detail, was too monocausal. His main difference from Gibbon lay in his interpretation of facts, rather than disputing any facts. He made it clear that he felt that Gibbon's thesis concerning "moral decay" was viable—but incomplete. Bury's judgment was that:

The gradual collapse of the Roman power ... was the consequence of a series of contingent events. No general causes can be assigned that made it inevitable.

Bury held that a number of crises arose simultaneously: economic decline, Germanic expansion, depopulation of Italy, dependency on Germanic foederati for the military, the disastrous (though Bury believed unknowing) treason of Stilicho, loss of martial vigor, Aetius' murder, the lack of any leader to replace Aetius—a series of misfortunes which, in combination, proved catastrophic:

The Empire had come to depend on the enrollment of barbarians, in large numbers, in the army, and ... it was necessary to render the service attractive to them by the prospect of power and wealth. This was, of course, a consequence of the decline in military spirit, and of depopulation, in the old civilised Mediterranean countries. The Germans in high command had been useful, but the dangers involved in the policy had been shown in the cases of Merobaudes and Arbogastes. Yet this policy need not have led to the dismemberment of the Empire, and but for that series of chances its western provinces would not have been converted, as and when they were, into German kingdoms. It may be said that a German penetration of western Europe must ultimately have come about. But even if that were certain, it might have happened in another way, at a later time, more gradually, and with less violence. The point of the present contention is that Rome's loss of her provinces in the fifth century was not an "inevitable effect of any of those features which have been rightly or wrongly described as causes or consequences of her general 'decline'". The central fact that Rome could not dispense with the help of barbarians for her wars (gentium barbararum auxilio indigemus) may be held to be the cause of her calamities, but it was a weakness which might have continued to be far short of fatal but for the sequence of contingencies pointed out above.

Peter Heather

Peter Heather, in his The Fall of the Roman Empire (2005), maintains the Roman imperial system with its sometimes violent imperial transitions and problematic communications notwithstanding, was in fairly good shape during the first, second, and part of the 3rd centuries AD. According to Heather, the first real indication of trouble was the emergence in Iran of the Sassanid Persian empire (226–651). As reviewed by one writer on Heather's writing,

The Sassanids were sufficiently powerful and internally cohesive to push back Roman legions from the Euphrates and from much of Armenia and southeast Turkey. Much as modern readers tend to think of the "Huns" as the nemesis of the Roman Empire, for the entire period under discussion it was the Persians who held the attention and concern of Rome and Constantinople. Indeed, 20–25% of the military might of the Roman Army was addressing the Persian threat from the late third century onward ... and upwards of 40% of the troops under the Eastern Emperors.

Heather goes on to state—in the tradition of Gibbon and Bury—that it took the Roman Empire about half a century to cope with the Sassanid threat, which it did by stripping the western provincial towns and cities of their regional taxation income. The resulting expansion of military forces in the Middle East was finally successful in stabilizing the frontiers with the Sassanids, but the reduction of real income in the provinces of the Empire led to two trends which, Heather says, had a negative long-term impact. First, the incentive for local officials to spend their time and money in the development of local infrastructure disappeared. Public buildings from the 4th century onward tended to be much more modest and funded from central budgets, as the regional taxes had dried up. Second, Heather says "the landowning provincial literati now shifted their attention to where the money was ... away from provincial and local politics to the imperial bureaucracies." Having set the scene of an Empire stretched militarily by the Sassanid threat, Heather then suggests, using archaeological evidence, that the Germanic tribes on the Empire's northern border had altered in nature since the 1st century. Contact with the Empire had increased their material wealth, and that in turn had led to disparities of wealth sufficient to create a ruling class capable of maintaining control over far larger groupings than had previously been possible. Essentially they had become significantly more formidable foes.

Heather then posits what amounts to a domino theory—namely that pressure on peoples very far away from the Empire could result in sufficient pressure on peoples on the Empire's borders to make them contemplate the risk of full scale immigration to the empire. Thus he links the Gothic invasion of 376 directly to Hunnic movements around the Black Sea in the decade before. In the same way he sees the invasions across the Rhine in 406 as a direct consequence of further Hunnic incursions in Germania; as such he sees the Huns as deeply significant in the fall of the Western Empire long before they themselves became a military threat to the Empire. He postulates that the Hunnic expansion caused unprecedented immigration in 376 and 406 by barbarian groupings who had become significantly more politically and militarily capable than in previous eras. This impacted an empire already at maximum stretch due to the Sassanid pressure. Essentially he argues that the external pressures of 376–470 could have brought the Western Empire down at any point in its history.

He disputes Gibbon's contention that Christianity and moral decay led to the decline. He also rejects the political infighting of the Empire as a reason, considering it was a systemic recurring factor throughout the Empire's history which, while it might have contributed to an inability to respond to the circumstances of the 5th century, it consequently cannot be blamed for them. Instead he places its origin squarely on outside military factors, starting with the Sassanids. Like Bury, he does not believe the fall was inevitable, but rather a series of events which came together to shatter the Empire. He differs from Bury, however, in placing the onset of those events far earlier in the Empire's timeline, with the Sassanid rise.

Bryan Ward-Perkins

Bryan Ward-Perkins's The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (2005) takes a traditional view tempered by modern discoveries, arguing that the empire's demise was caused by a vicious circle of political instability, foreign invasion, and reduced tax revenue. Essentially, invasions caused long-term damage to the provincial tax base, which lessened the Empire's medium- to long-term ability to pay and equip the legions, with predictable results. Likewise, constant invasions encouraged provincial rebellion as self-help, further depleting Imperial resources. Contrary to the trend among some historians of the "there was no fall" school, who view the fall of Rome as not necessarily a "bad thing" for the people involved, Ward-Perkins argues that in many parts of the former Empire the archaeological record indicates that the collapse was truly a disaster.

Ward-Perkins' theory, much like Bury's, and Heather's, identifies a series of cyclic events that came together to cause a definite decline and fall.

Transformation

Henri Pirenne

In the second half of the 19th century, some historians focused on the continuities between the Roman Empire and the post-Roman Germanic kingdoms rather than the rupture. In Histoire des institutions politiques de l'ancienne France (1875–89), Fustel de Coulanges argued that the barbarians simply contributed to an ongoing process of transforming Roman institutions.

Henri Pirenne continued this idea with the "Pirenne Thesis", published in the 1920s, which remains influential to this day. It holds that even after the barbarian invasions, the Roman way of doing things did not immediately change; barbarians came to Rome not to destroy it, but to take part in its benefits, and thus they tried to preserve the Roman way of life. The Pirenne Thesis regards the rise of the Frankish realm in Europe as a continuation of the Roman Empire, and thus validates the crowning of Charlemagne as the first Holy Roman Emperor as a successor of the Roman Emperors. According to Pirenne, the real break in Roman history occurred in the 7th and 8th centuries as a result of Arab expansion. Islamic conquest of the area of today's south-eastern Turkey, Syria, Palestine, North Africa, Spain and Portugal ruptured economic ties to western Europe, cutting the region off from trade and turning it into a stagnant backwater, with wealth flowing out in the form of raw resources and nothing coming back. This began a steady decline and impoverishment so that by the time of Charlemagne western Europe had become almost entirely agrarian at a subsistence level, with no long-distance trade. Pirenne's view on the continuity of the Roman Empire before and after the Germanic invasion has been supported by recent historians such as François Masai, Karl Ferdinand Werner, and Peter Brown.

Some modern critics have argued that the "Pirenne Thesis" erred on two counts: by treating the Carolingian realm as a Roman state and by overemphasizing the effect of the Islamic conquests on the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire. Other critics have argued that while Pirenne was correct in arguing for the continuity of the Empire beyond the sack of Rome, the Arab conquests in the 7th century may not have disrupted Mediterranean trade routes to the degree that Pirenne argued. Michael McCormick in particular has argued that some recently unearthed sources, such as collective biographies, describe new trade routes. Moreover, other records and coins document the movement of Islamic currency into the Carolingian Empire. McCormick has concluded that if money was coming in, some type of goods must have been going out – including slaves, timber, weapons, honey, amber, and furs.

Lucien Musset and the clash of civilizations

In the spirit of "Pirenne thesis", a school of thought pictured a clash of civilizations between the Roman and the Germanic world, a process taking place roughly between 3rd and 8th century.

The French historian Lucien Musset, studying the Barbarian invasions, argues the civilization of Medieval Europe emerged from a synthesis between the Graeco-Roman world and the Germanic civilizations penetrating the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire did not fall, did not decline, it just transformed but so did the Germanic populations which invaded it. To support this conclusion, beside the narrative of the events, he offers linguistic surveys of toponymy and anthroponymy, analyzes archaeological records, studies the urban and rural society, the institutions, the religion, the art, the technology.

Late Antiquity

Historians of Late Antiquity, a field pioneered by Peter Brown, have turned away from the idea that the Roman Empire fell at all – refocusing instead on Pirenne's thesis. They see a transformation occurring over centuries, with the roots of Medieval culture contained in Roman culture and focus on the continuities between the classical and Medieval worlds. Thus, it was a gradual process with no clear break. Brown argues in his book that:

Factors we would regard as natural in a 'crisis'—malaise caused by urbanization, public disasters, the intrusion of alien religious ideas, and a consequent heightening of religious hopes and fears—may not have bulked as large in the minds of the men of the late second and third centuries as we suppose... The towns of the Mediterranean were small towns. For all their isolation from the way of life of the villagers, they were fragile excrescences in a spreading countryside."