Holy Roman Empire | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

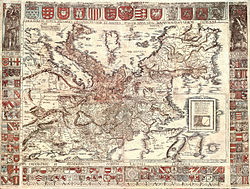

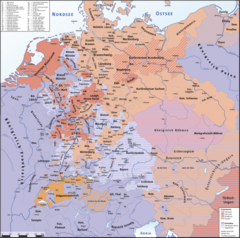

The change of territory of the Holy Roman Empire superimposed on present-day state borders | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | No single/fixed capital

| ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | German, Medieval Latin (administrative/liturgical/ Various | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism (800–1806) Lutheranism (1555–1806) Calvinism (1648–1806) see details | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Confederal elective monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||

• 800–814 | Charlemagne | ||||||||||||||||

• 962–973 | Otto I | ||||||||||||||||

• 1792–1806 | Francis II | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Imperial Diet | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages Early modern period | ||||||||||||||||

| 25 December 800 | |||||||||||||||||

• East Frankish Otto I is crowned Emperor of the Romans | 2 February 962 | ||||||||||||||||

• Conrad II assumes crown of the Kingdom of Burgundy | 2 February 1033 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25 September 1555 | |||||||||||||||||

| 24 October 1648 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 December 1805 | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 August 1806 | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1050 | 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1700 | 25,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1800 | 29,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Multiple: Thaler, Guilder, Groschen, Reichsthaler | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Holy Roman Empire (Latin: Sacrum Imperium Romanum; German: Heiliges Römisches Reich) was a multi-ethnic complex of territories in Western, Central and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

The empire was created by joining in personal union and with the imperial title the crown of the Kingdom of Italy with the Frankish crown, particularly the Kingdom of East Francia (Later Kingdom of Germany), as well as titles of other smaller territories. Soon, these kingdoms would be joined by the Kingdom of Burgundy and Kingdom of Bohemia. By the end of the 15th century, the empire was still in theory composed of three major blocks – Italy, Germany and Burgundy. Later territorially only the Kingdom of Germany and Bohemia remained, with the Burgundian territories lost to France. Although the Italian territories were formally part of the empire, the territories were ignored in the Imperial Reform and splintered into numerous de facto independent territorial entities. The status of Italy in particular varied throughout the 16th to 18th centuries. Some territories like Piedmont-Savoy became increasingly independent, while others became more dependent due to the extinction of their ruling noble houses causing these territories to often fall under the dominions of the Habsburgs and their cadet branches. Barring the loss of Franche-Comté in 1678, the external borders of the Empire did not change noticeably from the Peace of Westphalia – which acknowledged the exclusion of Switzerland and the Northern Netherlands, and the French protectorate over Alsace – to the dissolution of the Empire. At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, most of the Holy Roman Empire was included in the German Confederation, with the main exceptions being the Italian states.

On 25 December 800, Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne as Emperor, reviving the title in Western Europe, more than three centuries after the fall of the earlier ancient Western Roman Empire in 476. In theory and diplomacy, the Emperors were considered primus inter pares, regarded as first among equals among other Catholic monarchs across Europe. The title continued in the Carolingian family until 888 and from 896 to 899, after which it was contested by the rulers of Italy in a series of civil wars until the death of the last Italian claimant, Berengar I, in 924. The title was revived again in 962 when Otto I, King of Germany, was crowned emperor, fashioning himself as the successor of Charlemagne and beginning a continuous existence of the empire for over eight centuries. Some historians refer to the coronation of Charlemagne as the origin of the empire, while others prefer the coronation of Otto I as its beginning. Scholars generally concur, however, in relating an evolution of the institutions and principles constituting the empire, describing a gradual assumption of the imperial title and role.

The exact term "Holy Roman Empire" was not used until the 13th century, before which the empire was referred to variously as universum regnum ("the whole kingdom", as opposed to the regional kingdoms), imperium christianum ("Christian empire"), or Romanum imperium ("Roman empire"), but the Emperor's legitimacy always rested on the concept of translatio imperii, that he held supreme power inherited from the ancient emperors of Rome. The dynastic office of Holy Roman Emperor was traditionally elective through the mostly German prince-electors, the highest-ranking noblemen of the empire; they would elect one of their peers as "King of the Romans" to be crowned emperor by the Pope, although the tradition of papal coronations was discontinued in the 16th century.

The empire never achieved the extent of political unification as was formed to the west in the relatively centralized kingdom of France, evolving instead into a decentralised, limited elective monarchy composed of hundreds of sub-units: kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, prince-bishoprics, Free Imperial Cities, and eventually even individuals enjoying imperial immediacy, such as the imperial knights. The power of the emperor was limited, and while the various princes, lords, bishops, and cities of the empire were vassals who owed the emperor their allegiance, they also possessed an extent of privileges that gave them de facto independence within their territories. Emperor Francis II dissolved the empire on 6 August 1806 following the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine by Emperor Napoleon I the month before.

Name

The Empire was considered by the Roman Catholic Church to be the only legal successor of the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. Since Charlemagne, the realm was merely referred to as the Roman Empire. The term sacrum ("holy", in the sense of "consecrated") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was used beginning in 1157 under Frederick I Barbarossa ("Holy Empire"): the term was added to reflect Frederick's ambition to dominate Italy and the Papacy. The form "Holy Roman Empire" is attested from 1254 onward.

In a decree following the Diet of Cologne in 1512, the name was changed to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (German: Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation, Latin: Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Germanicæ), a form first used in a document in 1474. The new title was adopted partly because the Empire lost most of its territories in Italy and Burgundy to the south and west by the late 15th century, but also to emphasize the new importance of the German Imperial Estates in ruling the Empire due to the Imperial Reform.

By the end of the 18th century, the term "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation" fell out of official use. Contradicting the traditional view concerning that designation, Hermann Weisert has argued in a study on imperial titulature that, despite the claims of many textbooks, the name "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation" never had an official status and points out that documents were thirty times as likely to omit the national suffix as include it.

In a famous assessment of the name, the political philosopher Voltaire remarked sardonically: "This body which was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire."

In the modern period, the Empire was often informally called the German Empire (Deutsches Reich) or Roman-German Empire (Römisch-Deutsches Reich). After its dissolution through the end of the German Empire, it was often called "the old Empire" (das alte Reich). Beginning in 1923, early twentieth-century German nationalists and Nazi propaganda would identify the Holy Roman Empire as the First Reich (Reich meaning empire), with the German Empire as the Second Reich and either a future German nationalist state or Nazi Germany as the Third Reich.

History

Early Middle Ages

Carolingian period

As Roman power in Gaul declined during the 5th century, local Germanic tribes assumed control. In the late 5th and early 6th centuries, the Merovingians, under Clovis I and his successors, consolidated Frankish tribes and extended hegemony over others to gain control of northern Gaul and the middle Rhine river valley region. By the middle of the 8th century, however, the Merovingians were reduced to figureheads, and the Carolingians, led by Charles Martel, became the de facto rulers. In 751, Martel's son Pepin became King of the Franks, and later gained the sanction of the Pope. The Carolingians would maintain a close alliance with the Papacy.

In 768, Pepin's son Charlemagne became King of the Franks and began an extensive expansion of the realm. He eventually incorporated the territories of present-day France, Germany, northern Italy, the Low Countries and beyond, linking the Frankish kingdom with Papal lands.

Although antagonism about the expense of Byzantine domination had long persisted within Italy, a political rupture was set in motion in earnest in 726 by the iconoclasm of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian, in what Pope Gregory II saw as the latest in a series of imperial heresies. In 797, the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine VI was removed from the throne by his mother Irene who declared herself Empress. As the Latin Church only regarded a male Roman Emperor as the head of Christendom, Pope Leo III sought a new candidate for the dignity, excluding consultation with the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Charlemagne's good service to the Church in his defense of Papal possessions against the Lombards made him the ideal candidate. On Christmas Day of 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor, restoring the title in the West for the first time in over three centuries. This can be seen as symbolic of the papacy turning away from the declining Byzantine Empire towards the new power of Carolingian Francia. Charlemagne adopted the formula Renovatio imperii Romanorum ("renewal of the Roman Empire"). In 802, Irene was overthrown and exiled by Nikephoros I and henceforth there were two Roman Emperors.

After Charlemagne died in 814, the imperial crown passed to his son, Louis the Pious. Upon Louis' death in 840, it passed to his son Lothair, who was his co-ruler. By this point the territory of Charlemagne was divided into several territories (cf. Treaty of Verdun, Treaty of Prüm, Treaty of Meerssen and Treaty of Ribemont), and over the course of the later ninth century the title of Emperor was disputed by the Carolingian rulers of Western Francia and Eastern Francia, with first the western king (Charles the Bald) and then the eastern (Charles the Fat), who briefly reunited the Empire, attaining the prize.

After the death of Charles the Fat in 888 the Carolingian Empire broke apart, and was never restored. According to Regino of Prüm, the parts of the realm "spewed forth kinglets", and each part elected a kinglet "from its own bowels". After the death of Charles the Fat, those crowned emperor by the pope controlled only territories in Italy. The last such emperor was Berengar I of Italy, who died in 924.

Formation of the Holy Roman Empire

Around 900, autonomous stem duchies (Franconia, Bavaria, Swabia, Saxony, and Lotharingia) reemerged in East Francia. After the Carolingian king Louis the Child died without issue in 911, East Francia did not turn to the Carolingian ruler of West Francia to take over the realm but instead elected one of the dukes, Conrad of Franconia, as Rex Francorum Orientalium. On his deathbed, Conrad yielded the crown to his main rival, Henry the Fowler of Saxony (r. 919–36), who was elected king at the Diet of Fritzlar in 919. Henry reached a truce with the raiding Magyars, and in 933 he won a first victory against them in the Battle of Riade.

Henry died in 936, but his descendants, the Liudolfing (or Ottonian) dynasty, would continue to rule the Eastern kingdom for roughly a century. Upon Henry the Fowler's death, Otto, his son and designated successor, was elected King in Aachen in 936. He overcame a series of revolts from a younger brother and from several dukes. After that, the king managed to control the appointment of dukes and often also employed bishops in administrative affairs.

In 951, Otto came to the aid of Adelaide, the widowed queen of Italy, defeating her enemies, marrying her, and taking control over Italy. In 955, Otto won a decisive victory over the Magyars in the Battle of Lechfeld. In 962, Otto was crowned emperor by Pope John XII, thus intertwining the affairs of the German kingdom with those of Italy and the Papacy. Otto's coronation as Emperor marked the German kings as successors to the Empire of Charlemagne, which through the concept of translatio imperii, also made them consider themselves as successors to Ancient Rome.

The kingdom lacked a permanent capital city. Kings traveled between residences (called Kaiserpfalz) to discharge affairs, though each king preferred certain places; in Otto's case, this was the city of Magdeburg. Kingship continued to be transferred by election, but Kings often ensured their own sons were elected during their lifetimes, enabling them to keep the crown for their families. This only changed after the end of the Salian dynasty in the 12th century.

In 963, Otto deposed the current Pope John XII and chose Pope Leo VIII as the new pope (although John XII and Leo VIII both claimed the papacy until 964 when John XII died). This also renewed the conflict with the Eastern Emperor in Constantinople, especially after Otto's son Otto II (r. 967–83) adopted the designation imperator Romanorum. Still, Otto II formed marital ties with the east when he married the Byzantine princess Theophanu. Their son, Otto III, came to the throne only three years old, and was subjected to a power struggle and series of regencies until his age of majority in 994. Up to that time, he remained in Germany, while a deposed duke, Crescentius II, ruled over Rome and part of Italy, ostensibly in his stead.

In 996 Otto III appointed his cousin Gregory V the first German Pope. A foreign pope and foreign papal officers were seen with suspicion by Roman nobles, who were led by Crescentius II to revolt. Otto III's former mentor Antipope John XVI briefly held Rome, until the Holy Roman Emperor seized the city.

Otto died young in 1002, and was succeeded by his cousin Henry II, who focused on Germany.

Henry II died in 1024 and Conrad II, first of the Salian dynasty, was elected king only after some debate among dukes and nobles. This group eventually developed into the college of Electors.

The Holy Roman Empire eventually came to be composed of four kingdoms. The kingdoms were:

- Kingdom of Germany (part of the empire since 962),

- Kingdom of Italy (from 962 until 1801),

- Kingdom of Bohemia (from 1002 as the Duchy of Bohemia and raised to a kingdom in 1198),

- Kingdom of Burgundy (from 1032 to 1378). r

High Middle Ages

Investiture controversy

Kings often employed bishops in administrative affairs and often determined who would be appointed to ecclesiastical offices.[53]:101–134 In the wake of the Cluniac Reforms, this involvement was increasingly seen as inappropriate by the Papacy. The reform-minded Pope Gregory VII was determined to oppose such practices, which led to the Investiture Controversy with Henry IV (r. 1056–1106), the King of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperor.[53]:101–34

Henry IV repudiated the Pope's interference and persuaded his bishops to excommunicate the Pope, whom he famously addressed by his born name "Hildebrand", rather than his regnal name "Pope Gregory VII". The Pope, in turn, excommunicated the king, declared him deposed, and dissolved the oaths of loyalty made to Henry. The king found himself with almost no political support and was forced to make the famous Walk to Canossa in 1077, by which he achieved a lifting of the excommunication at the price of humiliation. Meanwhile, the German princes had elected another king, Rudolf of Swabia.

Henry managed to defeat Rudolf, but was subsequently confronted with more uprisings, renewed excommunication, and even the rebellion of his sons. After his death, his second son, Henry V, reached an agreement with the Pope and the bishops in the 1122 Concordat of Worms. The political power of the Empire was maintained, but the conflict had demonstrated the limits of the ruler's power, especially in regard to the Church, and it robbed the king of the sacral status he had previously enjoyed. The Pope and the German princes had surfaced as major players in the political system of the empire.

Ostsiedlung

As the result of Ostsiedlung, less-populated regions of Central Europe (i.e. the territory of today's Poland and Czech Republic) became German-speaking. Silesia became part of the Holy Roman Empire as the result of the local Piast dukes' push for autonomy from the Polish Crown. From the late 12th century, the Duchy of Pomerania was under the suzerainty of the Holy Roman Empire and the conquests of the Teutonic Order made that region German-speaking.

Hohenstaufen dynasty

When the Salian dynasty ended with Henry V's death in 1125, the princes chose not to elect the next of kin, but rather Lothair, the moderately powerful but already old Duke of Saxony. When he died in 1137, the princes again aimed to check royal power; accordingly they did not elect Lothair's favoured heir, his son-in-law Henry the Proud of the Welf family, but Conrad III of the Hohenstaufen family, the grandson of Emperor Henry IV and thus a nephew of Emperor Henry V. This led to over a century of strife between the two houses. Conrad ousted the Welfs from their possessions, but after his death in 1152, his nephew Frederick I "Barbarossa" succeeded him and made peace with the Welfs, restoring his cousin Henry the Lion to his – albeit diminished – possessions.

The Hohenstaufen rulers increasingly lent land to ministerialia, formerly non-free servicemen, who Frederick hoped would be more reliable than dukes. Initially used mainly for war services, this new class of people would form the basis for the later knights, another basis of imperial power. A further important constitutional move at Roncaglia was the establishment of a new peace mechanism for the entire empire, the Landfrieden, with the first imperial one being issued in 1103 under Henry IV at Mainz.

This was an attempt to abolish private feuds, between the many dukes and other people, and to tie the emperor's subordinates to a legal system of jurisdiction and public prosecution of criminal acts – a predecessor of the modern concept of "rule of law". Another new concept of the time was the systematic founding of new cities by the Emperor and by the local dukes. These were partly a result of the explosion in population; they also concentrated economic power at strategic locations. Before this, cities had only existed in the form of old Roman foundations or older bishoprics. Cities that were founded in the 12th century include Freiburg, possibly the economic model for many later cities, and Munich.

Frederick I, also called Frederick Barbarossa, was crowned emperor in 1155. He emphasized the "Romanness" of the empire, partly in an attempt to justify the power of the emperor independent of the (now strengthened) pope. An imperial assembly at the fields of Roncaglia in 1158 reclaimed imperial rights in reference to Justinian I's Corpus Juris Civilis. Imperial rights had been referred to as regalia since the Investiture Controversy but were enumerated for the first time at Roncaglia. This comprehensive list included public roads, tariffs, coining, collecting punitive fees, and the seating and unseating of office-holders. These rights were now explicitly rooted in Roman law, a far-reaching constitutional act.

Frederick's policies were primarily directed at Italy, where he clashed with the increasingly wealthy and free-minded cities of the north, especially Milan. He also embroiled himself in another conflict with the Papacy by supporting a candidate elected by a minority against Pope Alexander III (1159–81). Frederick supported a succession of antipopes before finally making peace with Alexander in 1177. In Germany, the Emperor had repeatedly protected Henry the Lion against complaints by rival princes or cities (especially in the cases of Munich and Lübeck). Henry gave only lackluster support to Frederick's policies, and, in a critical situation during the Italian wars, Henry refused the Emperor's plea for military support. After returning to Germany, an embittered Frederick opened proceedings against the Duke, resulting in a public ban and the confiscation of all Henry's territories. In 1190, Frederick participated in the Third Crusade, dying in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

During the Hohenstaufen period, German princes facilitated a successful, peaceful eastward settlement of lands that were uninhabited or inhabited sparsely by West Slavs. German-speaking farmers, traders, and craftsmen from the western part of the Empire, both Christians and Jews, moved into these areas. The gradual Germanization of these lands was a complex phenomenon that should not be interpreted in the biased terms of 19th-century nationalism. The eastward settlement expanded the influence of the empire to include Pomerania and Silesia, as did the intermarriage of the local, still mostly Slavic, rulers with German spouses. The Teutonic Knights were invited to Prussia by Duke Konrad of Masovia to Christianize the Prussians in 1226. The monastic state of the Teutonic Order (German: Deutschordensstaat) and its later German successor state of Prussia were never part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Under the son and successor of Frederick Barbarossa, Henry VI, the Hohenstaufen dynasty reached its apex. Henry added the Norman kingdom of Sicily to his domains, held English king Richard the Lionheart captive, and aimed to establish a hereditary monarchy when he died in 1197. As his son, Frederick II, though already elected king, was still a small child and living in Sicily, German princes chose to elect an adult king, resulting in the dual election of Frederick Barbarossa's youngest son Philip of Swabia and Henry the Lion's son Otto of Brunswick, who competed for the crown. Otto prevailed for a while after Philip was murdered in a private squabble in 1208 until he began to also claim Sicily.

Pope Innocent III, who feared the threat posed by a union of the empire and Sicily, was now supported by Frederick II, who marched to Germany and defeated Otto. After his victory, Frederick did not act upon his promise to keep the two realms separate. Though he had made his son Henry king of Sicily before marching on Germany, he still reserved real political power for himself. This continued after Frederick was crowned Emperor in 1220. Fearing Frederick's concentration of power, the Pope finally excommunicated him. Another point of contention was the Crusade, which Frederick had promised but repeatedly postponed. Now, although excommunicated, Frederick led the Sixth Crusade in 1228, which ended in negotiations and a temporary restoration of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Despite his imperial claims, Frederick's rule was a major turning point towards the disintegration of central rule in the Empire. While concentrated on establishing a modern, centralized state in Sicily, he was mostly absent from Germany and issued far-reaching privileges to Germany's secular and ecclesiastical princes: in the 1220 Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis, Frederick gave up a number of regalia in favour of the bishops, among them tariffs, coining, and fortification. The 1232 Statutum in favorem principum mostly extended these privileges to secular territories. Although many of these privileges had existed earlier, they were now granted globally, and once and for all, to allow the German princes to maintain order north of the Alps while Frederick concentrated on Italy. The 1232 document marked the first time that the German dukes were called domini terræ, owners of their lands, a remarkable change in terminology as well.

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia was a significant regional power during the Middle Ages. In 1212, King Ottokar I (bearing the title "king" since 1198) extracted a Golden Bull of Sicily (a formal edict) from the emperor Frederick II, confirming the royal title for Ottokar and his descendants, and the Duchy of Bohemia was raised to a kingdom. Bohemian kings would be exempt from all future obligations to the Holy Roman Empire except for participation in the imperial councils. Charles IV set Prague to be the seat of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Interregnum

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the German kingdom was divided between his son Conrad IV (died 1254) and the anti-king, William of Holland (died 1256). Conrad's death was followed by the Interregnum, during which no king could achieve universal recognition, allowing the princes to consolidate their holdings and become even more independent as rulers. After 1257, the crown was contested between Richard of Cornwall, who was supported by the Guelph party, and Alfonso X of Castile, who was recognized by the Hohenstaufen party but never set foot on German soil. After Richard's death in 1273, Rudolf I of Germany, a minor pro-Hohenstaufen count, was elected. He was the first of the Habsburgs to hold a royal title, but he was never crowned emperor. After Rudolf's death in 1291, Adolf and Albert were two further weak kings who were never crowned emperor.

Albert was assassinated in 1308. Almost immediately, King Philip IV of France began aggressively seeking support for his brother, Charles of Valois, to be elected the next King of the Romans. Philip thought he had the backing of the French Pope, Clement V (established at Avignon in 1309), and that his prospects of bringing the empire into the orbit of the French royal house were good. He lavishly spread French money in the hope of bribing the German electors. Although Charles of Valois had the backing of Henry, Archbishop of Cologne, a French supporter, many were not keen to see an expansion of French power, least of all Clement V. The principal rival to Charles appeared to be Rudolf, the Count Palatine.

Instead, Henry VII, of the House of Luxembourg, was elected with six votes at Frankfurt on 27 November 1308. Given his background, although he was a vassal of king Philip, Henry was bound by few national ties, an aspect of his suitability as a compromise candidate among the electors, the great territorial magnates who had lived without a crowned emperor for decades, and who were unhappy with both Charles and Rudolf. Henry of Cologne's brother, Baldwin, Archbishop of Trier, won over a number of the electors, including Henry, in exchange for some substantial concessions. Henry VII was crowned king at Aachen on 6 January 1309, and emperor by Pope Clement V on 29 June 1312 in Rome, ending the interregnum.

Changes in political structure

During the 13th century, a general structural change in how land was administered prepared the shift of political power towards the rising bourgeoisie at the expense of the aristocratic feudalism that would characterize the Late Middle Ages. The rise of the cities and the emergence of the new burgher class eroded the societal, legal and economic order of feudalism. Instead of personal duties, money increasingly became the common means to represent economic value in agriculture.

Peasants were increasingly required to pay tribute to their landlords. The concept of "property" began to replace more ancient forms of jurisdiction, although they were still very much tied together. In the territories (not at the level of the Empire), power became increasingly bundled: whoever owned the land had jurisdiction, from which other powers derived. However, that jurisdiction at the time did not include legislation, which was virtually non-existent until well into the 15th century. Court practice heavily relied on traditional customs or rules described as customary.

During this time, territories began to transform into the predecessors of modern states. The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were almost identical to the lands of the old Germanic tribes, e.g., Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded through imperial privileges.

In the 12th century the Hanseatic League established itself as a commercial and defensive alliance of the merchant guilds of towns and cities in the empire and all over northern and central Europe. It dominated marine trade in the Baltic Sea, the North Sea and along the connected navigable rivers. Each of the affiliated cities retained the legal system of its sovereign and, with the exception of the Free imperial cities, had only a limited degree of political autonomy. By the late 14th century, the powerful league enforced its interests with military means, if necessary. This culminated in a war with the sovereign Kingdom of Denmark from 1361 to 1370. The league declined after 1450.

Late Middle Ages

Rise of the territories after the Hohenstaufens

The difficulties in electing the king eventually led to the emergence of a fixed college of prince-electors (Kurfürsten), whose composition and procedures were set forth in the Golden Bull of 1356, which remained valid until 1806. This development probably best symbolizes the emerging duality between emperor and realm (Kaiser und Reich), which were no longer considered identical. The Golden Bull also set forth the system for election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The emperor now was to be elected by a majority rather than by consent of all seven electors. For electors the title became hereditary, and they were given the right to mint coins and to exercise jurisdiction. Also it was recommended that their sons learn the imperial languages – German, Latin, Italian, and Czech.

The shift in power away from the emperor is also revealed in the way the post-Hohenstaufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called Reichsgut, which always belonged to the king of the day and included many Imperial Cities. After the 13th century, the relevance of the Reichsgut faded, even though some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806. Instead, the Reichsgut was increasingly pawned to local dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire, but more frequently to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to establish control over the dukes. The direct governance of the Reichsgut no longer matched the needs of either the king or the dukes.

The kings beginning with Rudolf I of Germany increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support their power. In contrast with the Reichsgut, which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories were relatively compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolf I thus lent Austria and Styria to his own sons. In 1312, Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (Hausmacht): Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314, emperor 1328–47) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from his own lands in Bohemia. It was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

Imperial reform

The "constitution" of the Empire still remained largely unsettled at the beginning of the 15th century. Although some procedures and institutions had been fixed, for example by the Golden Bull of 1356, the rules of how the king, the electors, and the other dukes should cooperate in the Empire much depended on the personality of the respective king. It therefore proved somewhat damaging that Sigismund of Luxemburg (king 1410, emperor 1433–1437) and Frederick III of Habsburg (king 1440, emperor 1452–1493) neglected the old core lands of the empire and mostly resided in their own lands. Without the presence of the king, the old institution of the Hoftag, the assembly of the realm's leading men, deteriorated. The Imperial Diet as a legislative organ of the Empire did not exist at that time. The dukes often conducted feuds against each other – feuds that, more often than not, escalated into local wars.

Simultaneously, the Catholic Church experienced crises of its own, with wide-reaching effects in the Empire. The conflict between several papal claimants (two anti-popes and the "legitimate" Pope) ended only with the Council of Constance (1414–1418); after 1419 the Papacy directed much of its energy to suppressing the Hussites. The medieval idea of unifying all Christendom into a single political entity, with the Church and the Empire as its leading institutions, began to decline.

With these drastic changes, much discussion emerged in the 15th century about the Empire itself. Rules from the past no longer adequately described the structure of the time, and a reinforcement of earlier Landfrieden was urgently needed. While older scholarship presented this period as a time of total disorder and near-anarchy, new research has reassessed the German lands in the 15th century in a more positive light. Landfrieden was not only a matter imposed by kings (which might disappear in their absence), but was also upheld by regional leagues and alliances (also called "associations").

Princes, nobles and/or cities collaborated to keep the peace by adhering to collective treaties which stipulated methods for resolving disputes (ad hoc courts and arbitration) and joint military measures to defeat outlaws and declarers of feuds. Nevertheless, some members of the imperial estates (notably Berthold von Henneberg, archbishop of Mainz) sought a more centralized and institutionalized approach to regulating peace and justice, as (supposedly) had existed in earlier centuries of the Empire's history. During this time, the concept of "reform" emerged, in the original sense of the Latin verb re-formare – to regain an earlier shape that had been lost.

When Frederick III needed the dukes to finance a war against Hungary in 1486, and at the same time had his son (later Maximilian I) elected king, he faced a demand from the united dukes for their participation in an Imperial Court. For the first time, the assembly of the electors and other dukes was now called the Imperial Diet (German Reichstag) (to be joined by the Imperial Free Cities later). While Frederick refused, his more conciliatory son finally convened the Diet at Worms in 1495, after his father's death in 1493. Here, the king and the dukes agreed on four bills, commonly referred to as the Reichsreform (Imperial Reform): a set of legal acts to give the disintegrating Empire some structure.

For example, this act produced the Imperial Circle Estates and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), institutions that would – to a degree – persist until the end of the Empire in 1806. It took a few more decades for the new regulation to gain universal acceptance and for the new court to begin functioning effectively; the Imperial Circles were finalized in 1512. The King also made sure that his own court, the Reichshofrat, continued to operate in parallel to the Reichskammergericht. Also in 1512, the Empire received its new title, the Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation ("Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation").

Reformation and Renaissance

In 1516, Ferdinand II of Aragon, grandfather of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, died. Due to a combination of (1) the traditions of dynastic succession in Aragon, which permitted maternal inheritance with no precedence for female rule; (2) the insanity of Charles's mother, Joanna of Castile; and (3) the insistence by his remaining grandfather, Maximilian I, that he take up his royal titles, Charles initiated his reign in Castile and Aragon, a union which evolved into Spain, in conjunction with his mother. This ensured for the first time that all the realms of what is now Spain would be united by one monarch under one nascent Spanish crown.

The founding territories retained their separate governance codes and laws. In 1519, already reigning as Carlos I in Spain, Charles took up the imperial title as Karl V. The balance (and imbalance) between these separate inheritances would be defining elements of his reign and would ensure that personal union between the Spanish and German crowns would be short-lived. The latter would end up going to a more junior branch of the Habsburgs in the person of Charles's brother Ferdinand, while the senior branch continued to rule in Spain and the Burgundian inheritance in the person of Charles's son, Philip II of Spain.

In addition to conflicts between his Spanish and German inheritances, conflicts of religion would be another source of tension during the reign of Charles V. Before Charles's reign in the Holy Roman Empire began, in 1517, Martin Luther launched what would later be known as the Reformation. At this time, many local dukes saw it as a chance to oppose the hegemony of Emperor Charles V. The empire then became fatally divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities – Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg – becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic.

Baroque period

Charles V continued to battle the French and the Protestant princes in Germany for much of his reign. After his son Philip married Queen Mary of England, it appeared that France would be completely surrounded by Habsburg domains, but this hope proved unfounded when the marriage produced no children. In 1555, Paul IV was elected pope and took the side of France, whereupon an exhausted Charles finally gave up his hopes of a world Christian empire. He abdicated and divided his territories between Philip and Ferdinand of Austria. The Peace of Augsburg ended the war in Germany and accepted the existence of Protestantism in the form of Lutheranism, while Calvinism was still not recognized. Anabaptist, Arminian and other minor Protestant communities were also forbidden.

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the Emperor sought to avoid it. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt against Spain erupted, the Empire remained neutral, de facto allowing the Netherlands to depart the empire in 1581, a secession acknowledged in 1648. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine.

After Ferdinand died in 1564, his son Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, a strange man who preferred classical Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary, and the Protestant princes became upset over this.

Imperial power sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), which devastated the Empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but also seized considerable territory for themselves. The long conflict so bled the Empire that it never recovered its strength.

The actual end of the empire came in several steps. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which ended the Thirty Years' War, gave the territories almost complete independence. Calvinism was now allowed, but Anabaptists, Arminians and other Protestant communities would still lack any support and continue to be persecuted well until the end of the Empire. The Swiss Confederation, which had already established quasi-independence in 1499, as well as the Northern Netherlands, left the Empire. The Habsburg Emperors focused on consolidating their own estates in Austria and elsewhere.

At the Battle of Vienna (1683), the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Polish King John III Sobieski, decisively defeated a large Turkish army, stopping the western Ottoman advance and leading to the eventual dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in Europe. The army was one third forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and two thirds forces of the Holy Roman Empire.

Modern period

Prussia and Austria

By the rise of Louis XIV, the Habsburgs were chiefly dependent on their hereditary lands to counter the rise of Prussia, which possessed territories inside the Empire. Throughout the 18th century, the Habsburgs were embroiled in various European conflicts, such as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), the War of the Polish Succession (1733–1735), and the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The German dualism between Austria and Prussia dominated the empire's history after 1740.

French Revolutionary Wars and final dissolution

From 1792 onwards, revolutionary France was at war with various parts of the Empire intermittently.

The German mediatization was the series of mediatizations and secularizations that occurred between 1795 and 1814, during the latter part of the era of the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Era. "Mediatization" was the process of annexing the lands of one imperial estate to another, often leaving the annexed some rights. For example, the estates of the Imperial Knights were formally mediatized in 1806, having de facto been seized by the great territorial states in 1803 in the so-called Rittersturm. "Secularization" was the abolition of the temporal power of an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an abbot and the annexation of the secularized territory to a secular territory.

The empire was dissolved on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon at Austerlitz (see Treaty of Pressburg). Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French satellite. Francis' House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the empire, continuing to reign as Emperors of Austria and Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the aftermath of World War I.

The Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine was replaced by a new union, the German Confederation in 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It lasted until 1866 when Prussia founded the North German Confederation, a forerunner of the German Empire which united the German-speaking territories outside of Austria and Switzerland under Prussian leadership in 1871. This state developed into modern Germany.

The only princely member states of the Holy Roman Empire that have preserved their status as monarchies until today are the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the Principality of Liechtenstein. The only Free Imperial Cities still existing as states within Germany are Hamburg and Bremen. All other historic member states of the Holy Roman Empire were either dissolved or have adopted republican systems of government.

Institutions

The Holy Roman Empire was neither a centralized state nor a nation-state. Instead, it was divided into dozens – eventually hundreds – of individual entities governed by kings, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots, and other rulers, collectively known as princes. There were also some areas ruled directly by the Emperor. At no time could the Emperor simply issue decrees and govern autonomously over the Empire. His power was severely restricted by the various local leaders.

From the High Middle Ages onwards, the Holy Roman Empire was marked by an uneasy coexistence with the princes of the local territories who were struggling to take power away from it. To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such as France and England, the emperors were unable to gain much control over the lands that they formally owned. Instead, to secure their own position from the threat of being deposed, emperors were forced to grant more and more autonomy to local rulers, both nobles and bishops. This process began in the 11th century with the Investiture Controversy and was more or less concluded with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Several Emperors attempted to reverse this steady dilution of their authority but were thwarted both by the papacy and by the princes of the Empire.

Imperial estates

The number of territories represented in the Imperial Diet was considerable, numbering about 300 at the time of the Peace of Westphalia. Many of these Kleinstaaten ("little states") covered no more than a few square miles, and/or included several non-contiguous pieces, so the Empire was often called a Flickenteppich ("patchwork carpet"). An entity was considered a Reichsstand (imperial estate) if, according to feudal law, it had no authority above it except the Holy Roman Emperor himself. The imperial estates comprised:

- Territories ruled by a hereditary nobleman, such as a prince, archduke, duke, or count.

- Territories in which secular authority was held by an ecclesiastical dignitary, such as an archbishop, bishop, or abbot. Such an ecclesiastic or Churchman was a prince of the Church. In the common case of a prince-bishop, this temporal territory (called a prince-bishopric) frequently overlapped with his often larger ecclesiastical diocese, giving the bishop both civil and ecclesiastical powers. Examples are the prince-archbishoprics of Cologne, Trier, and Mainz.

- Free imperial cities and Imperial villages, which were subject only to the jurisdiction of the emperor.

- The scattered estates of the free Imperial Knights and Imperial Counts, immediate subject to the Emperor but unrepresented in the Imperial Diet.

A sum total of 1,500 Imperial estates has been reckoned.

The most powerful lords of the later empire were the Austrian Habsburgs, who ruled 240,000 square kilometers of land (96,665 square miles) within the Empire in the first half of the 17th century, mostly in modern-day Austria and Czechia. At the same time the lands ruled by the electors of Saxony, Bavaria, and Brandenburg (prior to the acquisition of Prussia) were all close to 40,000 square kilometers (15,445 square miles); the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (later the Elector of Hanover) had a territory around the same size. These were the largest of the German realms. The Elector of the Palatinate had significantly less at 20,000 square kilometers (7,772 square miles), and the ecclesiastical Electorates of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier were much smaller, with around 7,000 square kilometers each (2,702 square miles). Just larger than them, with roughly 7,000–10,000 square kilometers (2,702-3,861 square miles), were the Duchy of Württemberg, the Landgraviate of Hessen-Kassel, and the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. They were roughly matched in size by the prince-bishoprics of Salzburg and Münster. The majority of the other German territories, including the other prince-bishoprics, were under 5,000 square kilometers, the smallest being those of the Imperial Knights; around 1790 the Knights consisted of 350 families ruling a total of only 5,000 square kilometers collectively. Imperial Italy was more centralized, most of it c. 1600 being divided between Savoy (Savoy, Piedmont, Nice, Aosta), the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (Tuscany, bar Lucca), the Republic of Genoa (Liguria, Corisca), the duchies of Modena-Reggio and Parma-Piacenza (Emilia), and the Spanish Duchy of Milan (most of Lombardy), each with between half a million and one and a half million people. The Low Countries were also more coherent than Germany, being entirely under the dominion of the Spanish Netherlands as part of the Burgundian Circle, at least nominally.

| Ruler | 1648 | 1714 | 1748 | 1792 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austrian Habsburgs | 225,390 km^2 (32.8%) | 251,185 km^2 (36.5%) | 213,785 km^2 (31.1%) | 215,875 km^2 (31.4%) |

| Brandenburg Hohenzollerns | 70,469 km^2 (10.2%) | 77,702 km^2 (11.3%) | 124,122 km^2 (18.1%) | 131,822 km^2 (19.2%) |

| Other secular prince-electors | 89,333 km^2 (13.1%) | 122,823 km^2 (17.9%) | 123,153 km^2 (17.9%) | 121,988 km^2 (17.7%) |

| Other German rulers | 302,146 km^2 (44.0%) | 235,628 km^2 (34.3%) | 226,278 km^2 (32.9%) | 217,653 km^2 (31.7%) |

| Total | 687,338 | 687,338 | 687,338 | 687,338 |

King of the Romans

A prospective Emperor first had to be elected King of the Romans (Latin: Rex Romanorum; German: römischer König). German kings had been elected since the 9th century; at that point they were chosen by the leaders of the five most important tribes (the Salian Franks of Lorraine, Ripuarian Franks of Franconia, Saxons, Bavarians, and Swabians). In the Holy Roman Empire, the main dukes and bishops of the kingdom elected the King of the Romans.

In 1356, Emperor Charles IV issued the Golden Bull, which limited the electors to seven: the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, and the archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier. During the Thirty Years' War, the Duke of Bavaria was given the right to vote as the eighth elector, and the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (colloquially, Hanover) was granted a ninth electorate; additionally, the Napoleonic Wars resulted in several electorates being reallocated, but these new electors never voted before the Empire's dissolution. A candidate for election would be expected to offer concessions of land or money to the electors in order to secure their vote.

After being elected, the King of the Romans could theoretically claim the title of "Emperor" only after being crowned by the Pope. In many cases, this took several years while the King was held up by other tasks: frequently he first had to resolve conflicts in rebellious northern Italy or was quarreling with the Pope himself. Later Emperors dispensed with the papal coronation altogether, being content with the styling Emperor-Elect: the last Emperor to be crowned by the Pope was Charles V in 1530.

The Emperor had to be male and of noble blood. No law required him to be a Catholic, but as the majority of the Electors adhered to this faith, no Protestant was ever elected. Whether and to what degree he had to be German was disputed among the Electors, contemporary experts in constitutional law, and the public. During the Middle Ages, some Kings and Emperors were not of German origin, but since the Renaissance, German heritage was regarded as vital for a candidate in order to be eligible for imperial office.

Imperial Diet (Reichstag)

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag, or Reichsversammlung) was not a legislative body as is understood today, as its members envisioned it to be more like a central forum, where it was more important to negotiate than to decide. The Diet was theoretically superior to the emperor himself. It was divided into three classes. The first class, the Council of Electors, consisted of the electors, or the princes who could vote for King of the Romans. The second class, the Council of Princes, consisted of the other princes. The Council of Princes was divided into two "benches", one for secular rulers and one for ecclesiastical ones. Higher-ranking princes had individual votes, while lower-ranking princes were grouped into "colleges" by geography. Each college had one vote.

The third class was the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War.

Imperial courts

The Empire also had two courts: the Reichshofrat (also known in English as the Aulic Council) at the court of the King/Emperor, and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), established with the Imperial Reform of 1495 by Maximillian I. The Reichskammergericht and the Auclic Council were the two highest judicial instances in the Old Empire. The Imperial Chamber court's composition was determined by both the Holy Roman Emperor and the subject states of the Empire. Within this court, the Emperor appointed the chief justice, always a highborn aristocrat, several divisional chief judges, and some of the other puisne judges.

The Aulic Council held standing over many judicial disputes of state, both in concurrence with the Imperial Chamber court and exclusively on their own. The provinces Imperial Chamber Court extended to breaches of the public peace, cases of arbitrary distraint or imprisonment, pleas which concerned the treasury, violations of the Emperor's decrees or the laws passed by the Imperial Diet, disputes about property between immediate tenants of the Empire or the subjects of different rulers, and finally suits against immediate tenants of the Empire, with the exception of criminal charges and matters relating to imperial fiefs, which went to the Aulic Council.

Imperial circles

As part of the Imperial Reform, six Imperial Circles were established in 1500; four more were established in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not all) of the various states of the Empire for the purposes of defense, imperial taxation, supervision of coining, peace-keeping functions, and public security. Each circle had its own parliament, known as a Kreistag ("Circle Diet"), and one or more directors, who coordinated the affairs of the circle. Not all imperial territories were included within the imperial circles, even after 1512; the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were excluded, as were Switzerland, the imperial fiefs in northern Italy, the lands of the Imperial Knights, and certain other small territories like the Lordship of Jever.

Army

The Army of the Holy Roman Empire (German Reichsarmee, Reichsheer or Reichsarmatur; Latin exercitus imperii) was created in 1422 and as a result of the Napoleonic Wars came to an end even before the Empire. It must not be confused with the Imperial Army (Kaiserliche Armee) of the Emperor.

Despite appearances to the contrary, the Army of the Empire did not constitute a permanent standing army that was always at the ready to fight for the Empire. When there was danger, an Army of the Empire was mustered from among the elements constituting it, in order to conduct an imperial military campaign or Reichsheerfahrt. In practice, the imperial troops often had local allegiances stronger than their loyalty to the Emperor.

Administrative centres

Throughout the first half of its history the Holy Roman Empire was reigned by a travelling court. Kings and emperors toured between the numerous Kaiserpfalzes (Imperial palaces), usually resided for several weeks or months and furnished local legal matters, law and administration. Most rulers maintained one or a number of favourites Imperial palace sites, where they would advance development and spent most of their time: Charlemagne (Aachen from 794), Frederick II (Palermo 1220–1254), Wittelsbacher (Munich 1328–1347 and 1744–1745), Habsburger (Prague 1355–1437 and 1576–1611; and Vienna 1438–1576, 1611–1740 and 1745–1806).

This practice eventually ended during the 14th century, as the emperors of the Habsburg dynasty chose Vienna and Prague and the Wittelsbach rulers chose Munich as their permanent residences. These sites served however only as the individual residence for a particular sovereign. A number of cities held official status, where the Imperial Estates would summon at Imperial Diets, the deliberative assembly of the empire.

The Imperial Diet (Reichstag) resided variously in Paderborn, Bad Lippspringe, Ingelheim am Rhein, Diedenhofen (now Thionville), Aachen, Worms, Forchheim, Trebur, Fritzlar, Ravenna, Quedlinburg, Dortmund, Verona, Minden, Mainz, Frankfurt am Main, Merseburg, Goslar, Würzburg, Bamberg, Schwäbisch Hall, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Quierzy-sur-Oise, Speyer, Gelnhausen, Erfurt, Eger (now Cheb), Esslingen, Lindau, Freiburg, Cologne, Konstanz and Trier before it was moved permanently to Regensburg.

Until the 15th century the elected emperor was crowned and anointed by the Pope in Rome, among some exceptions in Ravenna, Bologna and Reims. Since 1508 (emperor Maximilian I) Imperial elections took place in Frankfurt am Main, Augsburg, Rhens, Cologne or Regensburg.

In December 1497 the Aulic Council (Reichshofrat) was established in Vienna.

In 1495 the Reichskammergericht was established, which variously resided in Worms, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Regensburg, Speyer and Esslingen before it was moved permanently to Wetzlar.

Foreign relations

The Habsburg royal family had its own diplomats to represent its interests. The larger principalities in the HRE, beginning around 1648, also did the same. The HRE did not have its own dedicated ministry of foreign affairs and therefore the Imperial Diet had no control over these diplomats; occasionally the Diet criticised them.

When Regensburg served as the site of the Diet, France and, in the late 1700s, Russia, had diplomatic representatives there. Denmark, Great Britain, and Sweden had land holdings in Germany and so had representation in the Diet itself. The Netherlands also had envoys in Regensburg. Regensburg was the place where envoys met as it was where representatives of the Diet could be reached.

Demographics

Population

Overall population figures for the Holy Roman Empire are extremely vague and vary widely. The empire of Charlemagne may have had as many as 20 million people. Given the political fragmentation of the later Empire, there were no central agencies that could compile such figures. Nevertheless, it is believed the demographic disaster of the Thirty Years War meant that the population of the Empire in the early 17th century was similar to what it was in the early 18th century; by one estimate, the Empire didn't exceed 1618 levels of population until 1750.

In the early 17th century, the electors held under their rule the following number of Imperial subjects:

- Habsburg monarchy: 5,350,000 (including 3 million in the Bohemian crown lands)

- Electorate of Saxony: 1,200,000

- Duchy of Bavaria (later Electorate of Bavaria): 800,000

- Electoral Palatinate: 600,000

- Electorate of Brandenburg: 350,000

- Electorates of Mainz, Trier, and Cologne: 300-400,000 altogether

While not electors, the Spanish Habsburgs had the second highest number of subjects within the Empire after the Austrian Habsburgs, with over 3 million in the early 17th century in the Burgundian Circle and Duchy of Milan.

Peter Wilson estimates the Empire's population at 25 million in 1700, of whom 5 million lived in Imperial Italy. By 1800 he estimates the Empire's population at 29 million (excluding Italy), with another 12.6 million held by the Austrians and Prussians outside of the Empire.

According to an overgenerous contemporary estimate of the Austrian War Archives for the first decade of the 18th century, the Empire—including Bohemia and the Spanish Netherlands—had a population of close to 28 million with a breakdown as follows:

- 65 ecclesiastical states with 14 percent of the total land area and 12 percent of the population;

- 45 dynastic principalities with 80 percent of the land and 80 percent of the population;

- 60 dynastic counties and lordships with 3 percent of the land and 3.5 percent of the population;

- 60 imperial towns with 1 percent of the land and 3.5 percent of the population;

- Imperial knights' territories, numbering into the several hundreds, with 2 percent of the land and 1 percent of the population.

German demographic historians have traditionally worked on estimates of the population of the Holy Roman Empire based on assumed population within the frontiers of Germany in 1871 or 1914. More recent estimates use less outdated criteria, but they remain guesswork. One estimate based on the frontiers of Germany in 1870 gives a population of some 15–17 million around 1600, declined to 10–13 million around 1650 (following the Thirty Years' War). Other historians who work on estimates of the population of the early modern Empire suggest the population declined from 20 million to some 16–17 million by 1650.

A credible estimate for 1800 gives 27-28 million inhabitants for the Empire (which at this point had already lost the remaining Low Countries, Italy, and the Left Bank of the Rhine in the 1797 Treaty of Campo Fornio) with an overall breakdown as follows:

- 9 million Austrian subjects (including Silesia, Bohemia and Moravia);

- 4 million Prussian subjects;

- 14–15 million inhabitants for the rest of the Empire.

There are also numerous estimates for the Italian states that were formally part of the Empire:

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| Duchy of Milan (Spanish) | 1,350,000 |

| Piedmont-Savoy | 1,200,000 |

| Republic of Genoa | 650,000 |

| Grand Duchy of Tuscany | 649,000 |

| Duchy of Parma-Piacenza | 250,000 |

| Duchy of Modena-Reggio | 250,000 |

| County of Gorizia and Gradisca (Austrian) | 130,000 |

| Republic of Lucca | 110,000 |

| Total | c. 4,600,000 |

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| Piedmont-Savoy | 2,400,000 |

| Duchy of Milan (Austrian) | 1,100,000 |

| Grand Duchy of Tuscany | 1,000,000 |

| Republic of Genoa | 500,000 |

| Duchy of Parma-Piacenza | 500,000 |

| Duchy of Modena-Reggio | 350,000 |

| Republic of Lucca | 100,000 |

| Total | c. 6,000,000 |

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns of the Empire by year:

- 1050: Regensburg 40,000 people. Rome 35,000. Mainz 30,000. Speyer 25,000. Cologne 21,000. Trier 20,000. Worms 20,000. Lyon 20,000. Verona 20,000. Florence 15,000.

- 1300–1350: Prague 77,000 people. Cologne 54,000 people. Aachen 21,000 people. Magdeburg 20,000 people. Nuremberg 20,000 people. Vienna 20,000 people. Danzig (now Gdańsk) 20,000 people. Straßburg (now Strasbourg) 20,000 people. Lübeck 15,000 people. Regensburg 11,000 people.

- 1500: Prague 70,000. Cologne 45,000. Nuremberg 38,000. Augsburg 30,000. Danzig (now Gdańsk) 30,000. Lübeck 25,000. Breslau (now Wrocław) 25,000. Regensburg 22,000. Vienna 20,000. Straßburg (now Strasbourg) 20,000. Magdeburg 18,000. Ulm 16,000. Hamburg 15,000.

- 1600: Milan 130,000. Prague 100,000. Vienna 50,000. Augsburg 45,000. Cologne 40,000. Nuremberg 40,000. Hamburg 40,000. Magdeburg 40,000. Breslau (now Wrocław) 40,000. Straßburg (now Strasbourg) 25,000. Lübeck 23,000. Ulm 21,000. Regensburg 20,000. Frankfurt am Main 20,000. Munich 20,000.

Religion

Catholicism constituted the single official religion of the Empire until 1555. The Holy Roman Emperor was always a Catholic.

Lutheranism was officially recognized in the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, and Calvinism in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. Those two constituted the only officially recognized Protestant denominations, while various other Protestant confessions such as Anabaptism, Arminianism, etc. coexisted illegally within the Empire. Anabaptism came in a variety of denominations, including Mennonites, Schwarzenau Brethren, Hutterites, the Amish, and multiple other groups.

Following the Peace of Augsburg, the official religion of a territory was determined by the principle cuius regio, eius religio according to which a ruler's religion determined that of his subjects. The Peace of Westphalia abrogated that principle by stipulating that the official religion of a territory was to be what it had been on 1 January 1624, considered to have been a "normal year". Henceforth, the conversion of a ruler to another faith did not entail the conversion of his subjects.

In addition, all Protestant subjects of a Catholic ruler and vice versa were guaranteed the rights that they had enjoyed on that date. While the adherents of a territory's official religion enjoyed the right of public worship, the others were allowed the right of private worship (in chapels without either spires or bells). In theory, no one was to be discriminated against or excluded from commerce, trade, craft or public burial on grounds of religion. For the first time, the permanent nature of the division between the Christian churches of the empire was more or less assumed.

A Jewish minority existed in the Holy Roman Empire.