| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zyprexa, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601213 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Atypical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60-65% |

| Protein binding | 93% |

| Metabolism | Liver (direct glucuronidation and CYP1A2 mediated oxidation) |

| Elimination half-life | 33 hours, 51.8 hours (elderly) |

| Excretion | Urine (57%; 7% as unchanged drug), faeces (30%) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.320 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

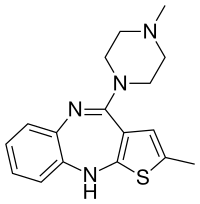

| Formula | C17H20N4S |

| Molar mass | 312.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 195 °C (383 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Practically insoluble in water mg/mL (20 °C) |

Olanzapine (sold under the trade name Zyprexa among others) is an atypical antipsychotic primarily used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. For schizophrenia, it can be used for both new-onset disease and long-term maintenance. It is taken by mouth or by injection into a muscle.

Common side effects include weight gain, movement disorders, dizziness, feeling tired, constipation, and dry mouth. Other side effects include low blood pressure with standing, allergic reactions, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, high blood sugar, seizures, and tardive dyskinesia. In older people with dementia, its use increases the risk of death. Use in the later part of pregnancy may result in a movement disorder in the baby for some time after birth. Although how it works is not entirely clear, it blocks dopamine and serotonin receptors.

Olanzapine was patented in 1991 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1996. It is available as a generic medication. In 2020, it was the 164th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions. Lilly also markets olanzapine in a fixed-dose combination with fluoxetine as olanzapine/fluoxetine (Symbyax).

Medical uses

It is approved by FDA for the following indications:

- schizophrenia

- Acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder and maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder.

- Adjunct to valproate, carbamazepine or lithium in the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder

- combination olanzapine/fluoxetine for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

In United Kingdom and Australia it is approved for schizophrenia, moderate to severe manic episodes, alone, or in combination with lithium or valproate and the short-term treatment of acute manic episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder.

Schizophrenia

The first-line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication. Olanzapine appears to be effective in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, treating acute exacerbations, and treating early-onset schizophrenia. The usefulness of maintenance therapy, however, is difficult to determine, as more than half of people in trials quit before the 6-week completion date. Treatment with olanzapine (like clozapine) may result in increased weight gain and increased glucose and cholesterol levels when compared to most other second-generation antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia.

Bipolar disorder

Olanzapine is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as a first-line therapy for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder. Other recommended first-line treatments are aripiprazole, haloperidol, quetiapine, and risperidone. It is recommended in combination with fluoxetine as a first-line therapy for acute bipolar depression, and as a second-line treatment by itself for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

The Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommends olanzapine as a first-line maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder and the combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine as second-line treatment for bipolar depression.

A review on the efficacy of olanzapine as maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar disorder was published by Dando & Tohen in 2006. A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that olanzapine with fluoxetine was the most effective among nine treatments for bipolar depression included in the analysis.

Other uses

Olanzapine may be useful in promoting weight gain in underweight adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa. However, no improvement of psychological symptoms was noted.

Olanzapine has been shown to be helpful in addressing a range of anxiety and depressive symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders, and has since been used in the treatment of a range of mood and anxiety disorders. Olanzapine is no less effective than lithium or valproate and more effective than placebo in treating bipolar disorder. It has also been used for Tourette syndrome and stuttering.

Olanzapine has been studied for the treatment of hyperactivity, aggressive behavior, and repetitive behaviors in autism.

Olanzapine is frequently prescribed off-label for the treatment of insomnia, including difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep, even though such use is not recommended. The daytime sedation experienced with olanzapine is generally comparable to quetiapine and lurasidone, which is a frequent complaint in clinical trials. In some cases, the sedation due to olanzapine impaired the ability of people to wake up at a consistent time every day. Some evidence of efficacy for treating insomnia is seen; however, side effects such as dyslipidemia and neutropenia, which may possibly be observed even at low doses, outweigh any potential benefits for insomnia that is not due to an underlying mental health condition.

Olanzapine has been recommended to be used in antiemetic regimens in people receiving chemotherapy that has a high risk for vomiting.

Specific populations

Pregnancy and lactation

Olanzapine is associated with the highest placental exposure of any atypical antipsychotic. Despite this, the available evidence suggests it is safe during pregnancy, although the evidence is insufficiently strong to say anything with a high degree of confidence. Olanzapine is associated with weight gain, which according to recent studies, may put olanzapine-treated patients' offspring at a heightened risk for neural tube defects (e.g. spina bifida). Breastfeeding in women taking olanzapine is advised against because olanzapine is secreted in breast milk, with one study finding that the exposure to the infant is about 1.8% that of the mother.

Elderly

Citing an increased risk of stroke, in 2004, the Committee on the Safety of Medicines in the UK issued a warning that olanzapine and risperidone, both atypical antipsychotic medications, should not be given to elderly patients with dementia. In the U.S., olanzapine comes with a black box warning for increased risk of death in elderly patients. It is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis. A BBC investigation in June 2008 found that this advice was being widely ignored by British doctors. Evidence suggested that the elderly are more likely to experience weight gain on olanzapine compared to aripiprazole and risperidone.

Adverse effects

The principal side effect of olanzapine is weight gain, which may be profound in some cases and/or associated with derangement in blood-lipid and blood-sugar profiles (see section metabolic effects). A 2013 meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerance of 15 antipsychotic drugs (APDs) found that it had the highest propensity for causing weight gain out of the 15 APDs compared with an SMD of 0.74. Extrapyramidal side effects, although potentially serious, are infrequent to rare from olanzapine, but may include tremors and muscle rigidity.

Aripiprazole, asenapine, clozapine, quetiapine and olanzapine, in comparison to other antipsychotic drugs, are less frequently associated with hyperprolactinaemia. Although these drugs can cause transient or sustained hyperprolactinaemia, the risk is much lower. Owing to its partial dopaminergic agonist effect, aripiprazole is likely to reduce prolactin levels and, in some patients, can cause hypoprolactinaemia. Although olanzapine causes an early dose-related rise in prolactin, this is less frequent and less marked than that seen with haloperidol, and is usually transient. A rise in prolactin is seen in about half of patients on olanzapine compared to over 90% of those taking risperidone, and enduring increases were less frequent in those taking olanzapine.

It is not recommended to be used by IM injection in acute myocardial infarction, bradycardia, recent heart surgery, severe hypotension, sick sinus syndrome, and unstable angina.

Several patient groups are at a heightened risk of side effects from olanzapine and antipsychotics in general. Olanzapine may produce nontrivial high blood sugar in people with diabetes mellitus. Likewise, the elderly are at a greater risk of falls and accidental injury. Young males appear to be at heightened risk of dystonic reactions, although these are relatively rare with olanzapine. Most antipsychotics, including olanzapine, may disrupt the body's natural thermoregulatory systems, thus permitting excursions to dangerous levels when situations (exposure to heat, strenuous exercise) occur.

Other side effects include galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and erectile dysfunction (impotence).

Drug-induced OCD

Many different types of medication can create or induce pure obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in patients who have never had symptoms before. A new chapter about OCD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (2013) now specifically includes drug-induced OCD.

Metabolic effects

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all atypical antipsychotics to include a warning about the risk of developing hyperglycemia and diabetes, both of which are factors in the metabolic syndrome. These effects may be related to the drugs' ability to induce weight gain, although some reports have been made of metabolic changes in the absence of weight gain. Studies have indicated that olanzapine carries a greater risk of causing and exacerbating diabetes than another commonly prescribed atypical antipsychotic, risperidone. Of all the atypical antipsychotics, olanzapine is one of the most likely to induce weight gain based on various measures. The effect is dose dependent in humans and animal models of olanzapine-induced metabolic side effects. There are some case reports of olanzapine-induced diabetic ketoacidosis. Olanzapine may decrease insulin sensitivity, though one 3-week study seems to refute this. It may also increase triglyceride levels.

Despite weight gain, a large multicenter, randomized National Institute of Mental Health study found that olanzapine was better at controlling symptoms because patients were more likely to remain on olanzapine than the other drugs. One small, open-label, nonrandomized study suggests that taking olanzapine by orally dissolving tablets may induce less weight gain, but this has not been substantiated in a blinded experimental setting.

Post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome

Postinjection delirium/sedation syndrome (PDSS) is a rare syndrome that is specific to the long-acting injectable formulation of olanzapine, olanzapine pamoate. The incidence of PDSS with olanzapine pamoate is estimated to be 0.07% of administrations, and is unique among other second-generation, long-acting antipsychotics (e.g. paliperidone palmitate), which do not appear to carry the same risk. PDSS is characterized by symptoms of delirium (e.g. confusion, difficulty speaking, and uncoordinated movements) and sedation. Most people with PDSS exhibit both delirium and sedation (83%). Although less specific to PDSS, a majority of cases (67%) involved a feeling of general discomfort. PDSS may occur due to accidental injection and absorption of olanzapine pamoate into the bloodstream, where it can act more rapidly, as opposed to slowly distributing out from muscle tissue. Using the proper, intramuscular-injection technique for olanzapine pamoate helps to decrease the risk of PDSS, though it does not eliminate it entirely. This is why the FDA advises that people who are injected with olanzapine pamoate be watched for 3 hours after administration, in the event that PDSS occurs.

Animal toxicology

Olanzapine has demonstrated carcinogenic effects in multiple studies when exposed chronically to female mice and rats, but not male mice and rats. The tumors found were in either the liver or mammary glands of the animals.

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse. Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite. Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping. Less commonly, vertigo, numbness, or muscle pains may occur. Symptoms generally resolve after a short time.

Tentative evidence indicates that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis. It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated. Rarely, tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.

Overdose

Symptoms of an overdose include tachycardia, agitation, dysarthria, decreased consciousness, and coma. Death has been reported after an acute overdose of 450 mg, but also survival after an acute overdose of 2000 mg. Fatalities generally have occurred with olanzapine plasma concentrations greater than 1000 ng/mL post mortem, with concentrations up to 5200 ng/mL recorded (though this might represent confounding by dead tissue, which may release olanzapine into the blood upon death). No specific antidote for olanzapine overdose is known, and even physicians are recommended to call a certified poison control center for information on the treatment of such a case. Olanzapine is considered moderately toxic in overdose, more toxic than quetiapine, aripiprazole, and the SSRIs, and less toxic than the monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants.

Interactions

Drugs or agents that increase the activity of the enzyme CYP1A2, notably tobacco smoke, may significantly increase hepatic first-pass clearance of olanzapine; conversely, drugs that inhibit CYP1A2 activity (examples: ciprofloxacin, fluvoxamine) may reduce olanzapine clearance. Carbamazepine, a known enzyme inducer, has decreased the concentration/dose ration of olanzapine by 33% compared to olanzapine alone. Another enzyme inducer, ritonavir, has also been shown to decrease the body's exposure to olanzapine, due to its induction of the enzymes CYP1A2 and uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT). Probenecid increases the total exposure (area under the curve) and maximum plasma concentration of olanzapine. Although olanzapine's metabolism includes the minor metabolic pathway of CYP2D6, the presence of the CYP2D6 inhibitor fluoxetine does not have a clinically significant effect on olanzapine's clearance.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Olanzapine was first discovered while searching for a chemical analog of clozapine that would not require hematological monitoring. Investigation on a series of thiophene isosteres on 1 of the phenyl rings in clozapine, a thienobenzodiazepine analog (olanzapine) was discovered.

Olanzapine has a higher affinity for 5-HT2A serotonin receptors than D2 dopamine receptors, which is a common property of most atypical antipsychotics, aside from the benzamide antipsychotics such as amisulpride along with the nonbenzamides aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, blonanserin, cariprazine, melperone, and perospirone.

In one study D2 receptor occupancy was 60% with low-dose olanzapine (5 mg/day) and occupancy with high dose at 83% (20 mg/day). In the usual clinical dose range of 10–20 mg/day, D2 receptor occupancy varied from 71% to 80%.

Olanzapine occupancy at 5-HT2A receptor are high at all doses (5 mg to 20 mg). It is reported that 5 mg dose of olanzapine produced a mean occupancy of 85% at 5 mg, 88% at 10 mg, and 93% at 20 mg dose.

Olanzapine had the highest affinity of any second-generation antipsychotic towards the P-glycoprotein in one in vitro study. P-glycoprotein transports a myriad of drugs across a number of different biological membranes (found in numerous body systems) including the blood–brain barrier (a semipermeable membrane that filters the contents of blood prior to it reaching the brain); P-GP inhibition could mean that less brain exposure to olanzapine results from this interaction with the P-glycoprotein. A relatively large quantity of commonly encountered foods and medications inhibit P-GP, and pharmaceuticals fairly commonly are either substrates of P-GP, or inhibit its action; both substrates and inhibitors of P-GP effectively increase the permeability of the blood–brain barrier to P-GP substrates and subsequently increase the central activity of the substrate, while reducing the local effects on the GI tract. The mediation of olanzapine in the central nervous system by P-GP means that any other substance or drug that interacts with P-GP increases the risk for toxic accumulations of both olanzapine and the other drug.

Olanzapine is a potent antagonist of the muscarinic M3 receptor, which may underlie its diabetogenic side effects. Additionally, it also exhibits a relatively low affinity for serotonin 5-HT1, GABAA, beta-adrenergic receptors, and benzodiazepine binding sites.

Although antagonistic effects of olanzapine at 5-HT2c alone is not associated with weight gain, olanzapine antagonism at histaminergic H1, and muscarinic M3 receptors have been implicated in weight gain.

The mode of action of olanzapine's antipsychotic activity is unknown. It may involve antagonism of dopamine and serotonin receptors. Antagonism of dopamine receptors is associated with extrapyramidal effects such as tardive dyskinesia (TD), and with therapeutic effects. Antagonism of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors is associated with anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth and constipation; in addition, it may suppress or reduce the emergence of extrapyramidal effects for the duration of treatment, but it offers no protection against the development of TD. In common with other second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics, olanzapine poses a relatively low risk of extrapyramidal side effects including TD, due to its higher affinity for the 5HT2A receptor over the D2 receptor.

Antagonizing H1 histamine receptors causes sedation and may cause weight gain, although antagonistic actions at serotonin 5-HT2C and dopamine D2 receptors have also been associated with weight gain and appetite stimulation.

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism

Olanzapine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system; principally by isozyme 1A2 (CYP1A2) and to a lesser extent by CYP2D6. By these mechanisms, more than 40% of the oral dose, on average, is removed by the hepatic first-pass effect. Clearance of olanzapine appears to vary by sex; women have roughly 25% lower clearance than men. Clearance of olanzapine also varies by race; in self-identified African Americans or Blacks, olanzapine's clearance was 26% higher. A difference in the clearance is not apparent between individuals identifying as Caucasian, Chinese, or Japanese. Routine, pharmacokinetic monitoring of olanzapine plasma levels is generally unwarranted, though unusual circumstances (e.g. the presence of drug–drug interactions) or a desire to determine if patients are taking their medicine may prompt its use.

Chemistry

Olanzapine is unusual in having four well-characterised crystalline polymorphs and many hydrated forms.

Chemical synthesis

The preparation of olanzapine was first disclosed in a series of patents from Eli Lilly & Co. in the 1990s. In the final two steps, 5-methyl-2-[(2-nitrophenyl)amino]-3-thiophenecarbonitrile was reduced with stannous chloride in ethanol to give the substituted thienobenzodiazepine ring system, and this was treated with methylpiperazine in a mixture of dimethyl sulfoxide and toluene as solvent to produce the drug.

Society and culture

Regulatory status

Olanzapine is approved by the US FDA for:

- Treatment—in combination with fluoxetine—of depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder (December 2003).

- Long-term treatment of bipolar I disorder (January 2004).

- Long-term treatment—in combination with fluoxetine—of resistant depression (March 2009)

- Oral formulation: acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adults, acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (monotherapy and in combination with lithium or sodium valproate)

- Intramuscular formulation: acute agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar I mania in adults

- Oral formulation combined with fluoxetine: treatment of acute depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults, or treatment of acute, resistant depression in adults

- Treatment of the manifestations of psychotic disorders (September 1996 – March 2000).

- Short-term treatment of acute manic episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (March 2000)

- Short-term treatment of schizophrenia instead of the management of the manifestations of psychotic disorders (March 2000)

- Maintaining treatment response in schizophrenic patients who had been stable for about eight weeks and were then followed for a period of up to eight months (November 2000)

The drug became generic in 2011. Sales of Zyprexa in 2008 were $2.2 billion in the US and $4.7 billion worldwide.

Controversy and litigation

Eli Lilly has faced many lawsuits from people who claimed they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa, as well as by various governmental entities, insurance companies, and others. Lilly produced a large number of documents as part of the discovery phase of this litigation, which started in 2004; the documents were ruled to be confidential by a judge and placed under seal, and later themselves became the subject of litigation.

In 2006, Lilly paid $700 million to settle around 8,000 of these lawsuits, and in early 2007, Lilly settled around 18,000 suits for $500 million, which brought the total Lilly had paid to settle suits related to the drug to $1.2 billion.

A December 2006 New York Times article based on leaked company documents concluded that the company had engaged in a deliberate effort to downplay olanzapine's side effects. The company denied these allegations and stated that the article had been based on cherry-picked documents. The documents were provided to the Times by Jim Gottstein, a lawyer who represented mentally ill patients, who obtained them from a doctor, David Egilman, who was serving as an expert consultant on the case. After the documents were leaked to online peer-to-peer, file-sharing networks by Will Hall and others in the psychiatric survivors movement, who obtained copies, in 2007 Lilly filed a protection order to stop the dissemination of some of the documents, which Judge Jack B. Weinstein of the Brooklyn Federal District Court granted. Judge Weinstein also criticized the New York Times reporter, Gottstein, and Egilman in the ruling. The Times of London also received the documents and reported that as early as 1998, Lilly considered the risk of drug-induced obesity to be a "top threat" to Zyprexa sales. On October 9, 2000, senior Lilly research physician Robert Baker noted that an academic advisory board to which he belonged was "quite impressed by the magnitude of weight gain on olanzapine and implications for glucose."

Lilly had threatened Egilman with criminal contempt charges regarding the documents he took and provided to reporters; in September 2007, he agreed to pay Lilly $100,000 in return for the company's agreement to drop the threat of charges.

In September 2008, Judge Weinstein issued an order to make public Lilly's internal documents about the drug in a different suit brought by insurance companies, pension funds, and other payors.

In March 2008, Lilly settled a suit with the state of Alaska, and in October 2008, Lilly agreed to pay $62 million to 32 states and the District of Columbia to settle suits brought under state consumer protection laws.

In 2009, Eli Lilly pleaded guilty to a US federal criminal misdemeanor charge of illegally marketing Zyprexa for off-label use and agreed to pay $1.4 billion. The settlement announcement stated "Eli Lilly admits that between September 1999 and March 31, 2001, the company promoted Zyprexa in elderly populations as treatment for dementia, including Alzheimer's dementia. Eli Lilly has agreed to pay a $515 million criminal fine and to forfeit an additional $100 million in assets."

The outcomes described here, and their legal ramifications, were fueled by motions and appeals that were not resolved until 2010. In 2021, Gottstein summarized this tangle of legal activities, and their impact on the political landscape of psychiatry and antipsychiatry in the US, in The Zyprexa Papers.

Trade names

Olanzapine is generic and available under many trade names worldwide.

Dosage forms

Olanzapine is marketed in a number of countries, with tablets ranging from 2.5 to 20 mg. Zyprexa (and generic olanzapine) is available as an orally disintegrating "wafer", which rapidly dissolves in saliva. It is also available in 10-mg vials for intramuscular injection.

Research

Olanzapine has been studied as an antiemetic, particularly for the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

In general, olanzapine appears to be about as effective as aprepitant for the prevention of CINV, though some concerns remain for its use in this population. For example, concomitant use of metoclopramide or haloperidol increases the risk for extrapyramidal symptoms. Otherwise, olanzapine appears to be fairly well tolerated for this indication, with somnolence being the most common side effect.

Olanzapine has been considered as part of an early psychosis approach for schizophrenia. The Prevention through Risk Identification, Management, and Education study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and Eli Lilly, tested the hypothesis that olanzapine might prevent the onset of psychosis in people at very high risk for schizophrenia. The study examined 60 patients with prodromal schizophrenia, who were at an estimated risk of 36–54% of developing schizophrenia within a year, and treated half with olanzapine and half with placebo. In this study, patients receiving olanzapine did not have a significantly lower risk of progressing to psychosis (16.1% vs 37.9%). Olanzapine was effective for treating the prodromal symptoms, but was associated with significant weight gain.