| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛsəˈtæləˌpræm/ ⓘ |

| Trade names | Cipralex, Lexapro, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603005 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% |

| Protein binding | ~56% |

| Metabolism | Liver, specifically the enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 |

| Metabolites | desmethylcitalopram, didesmethylcitalopram |

| Elimination half-life | 27–32 hours |

Escitalopram, sold under the brand names Lexapro and Cipralex, among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. Escitalopram is mainly used to treat major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. It is taken by mouth, available commercially as an oxalate salt exclusively.

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, nausea, sexual problems, and feeling tired. More serious side effects may include suicidal thoughts in people up to the age of 24 years. It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe. Escitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer of citalopram (which exists as a racemate), hence the name es-citalopram.

Escitalopram was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002. Escitalopram is rarely replaced by twice the dose of citalopram, though escitalopram is safer and more effective. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. In 2020, it was the fifteenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 30 million prescriptions.

Medical uses

Escitalopram has FDA approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and adults, and generalized anxiety disorder in adults. In European countries and the United Kingdom, it is approved for depression (MDD) and anxiety disorders; these include: general anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. In Australia it is approved for major depressive disorder.

Depression

Escitalopram is among the most effective and well-tolerated antidepressants for the short-term (acute) treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. It is also the safest one to give to children and adolescents.

Controversy existed regarding the effectiveness of escitalopram compared with its predecessor, citalopram. The importance of this issue followed from the greater cost of escitalopram relative to the generic mixture of isomers of citalopram, prior to the expiration of the escitalopram patent in 2012, which led to charges of evergreening. Accordingly, this issue has been examined in at least 10 different systematic reviews and meta analyses. As of 2012, reviews had concluded (with caveats in some cases) that escitalopram is modestly superior to citalopram in efficacy and tolerability.

Anxiety disorders

Escitalopram appears to be effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder, with relapse on escitalopram at 20% rather than placebo at 50%, which translates to a number needed to treat of 3.33. Escitalopram appears effective in treating social anxiety disorder as well.

Other

Escitalopram is effective in reducing the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, whether taken continuously or in the luteal phase only.

Side effects

Escitalopram, like other SSRIs, has been shown to affect sexual function, causing side effects such as decreased libido, delayed ejaculation, and anorgasmia.

There is also evidence that SSRIs may cause an increase in suicidal ideation. An analysis conducted by the FDA found a statistically insignificant 1.5 to 2.4-fold (depending on the statistical technique used) increase of suicidality among the adults treated with escitalopram for psychiatric indications. The authors of a related study note the general problem with statistical approaches: due to the rarity of suicidal events in clinical trials, it is hard to draw firm conclusions with a sample smaller than two million patients.

Citalopram and escitalopram are associated with dose-dependent QT interval prolongation and should not be used in those with congenital long QT syndrome or known pre-existing QT interval prolongation, or in combination with other medicines that prolong the QT interval. ECG measurements should be considered for patients with cardiac disease, and electrolyte disturbances should be corrected before starting treatment. In December 2011, the UK implemented new restrictions on the maximum daily doses at 20 mg for adults and 10 mg for those older than 65 years or with liver impairment. There are concerns of higher rates of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes compared with other SSRIs. The US Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada did not similarly order restrictions on escitalopram dosage, only on its predecessor citalopram.

Very common effects

Very common effects (>10% incidence) include:

- Headache (24%)

- Nausea (18%)

- Ejaculation disorder (9–14%)

- Somnolence (4–13%)

- Insomnia (7–12%)

Common (1–10% incidence)

Common effects (1–10% incidence) include:

- Abnormal dreams

- Anisocoria

- Anorgasmia

- Anxiety

- Arthralgia (joint pain)

- Constipation

- Decreased or increased appetite

- Diarrhea

- Dilated pupils

- Dizziness

- Dry mouth

- Excessive sweating

- Fatigue

- Impotence (erectile dysfunction)

- Insomnia

- Libido changes

- Myalgia (muscular aches and pains)

- Paraesthesia (abnormal skin sensation)

- Pyrexia (fever)

- Restlessness

- Sinusitis (nasal congestion)

- Somnolence (sleepiness)

- Tremor

- Vomiting

- Yawning

Psychomotor effects

The most common effect is fatigue or somnolence, particularly in older adults, although patients with pre-existing daytime sleepiness and fatigue may experience paradoxical improvement of these symptoms. Escitalopram has not been shown to affect serial reaction time, logical reasoning, serial subtraction, multitask, or Mackworth Clock task performance.

Discontinuation symptoms

Escitalopram discontinuation, particularly abruptly, may cause certain withdrawal symptoms such as "electric shock" sensations, colloquially called "brain shivers" or "brain zaps" by those affected. Frequent symptoms in one study were dizziness (44%), muscle tension (44%), chills (44%), confusion or trouble concentrating (40%), amnesia (28%), and crying (28%). Very slow tapering was recommended. There have been spontaneous reports of discontinuation of Lexapro and other SSRIs and SNRIs, especially when abrupt, leading to dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, anxiety, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, and hypomania. Other symptoms such as panic attacks, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), mania, worsening of depression, and suicidal ideation can emerge when the dose is adjusted down.

Sexual dysfunction

Some people experience persistent sexual side effects when taking SSRIs or after discontinuing them. Symptoms of medication-induced sexual dysfunction from antidepressants include difficulty with orgasm, erection, or ejaculation. Other symptoms may be genital anesthesia, anhedonia, decreased libido, vaginal lubrication issues, and nipple insensitivity in women. Rates are unknown, and there is no established treatment.

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including escitalopram) is associated with shorter duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points). Antidepressant exposure is not associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion. There is a tentative association of SSRI use during pregnancy with heart problems in the baby. The advantages of their use during pregnancy may thus outweigh the possible negative effects on the baby.

Overdose

Excessive doses of escitalopram usually cause relatively minor untoward effects, such as agitation and tachycardia. However, dyskinesia, hypertonia, and clonus may occur in some cases. Therapeutic blood levels of escitalopram are usually in the range of 20–80 μg/L but may reach 80–200 μg/L in the elderly, patients with hepatic dysfunction, those who are poor CYP2C19 metabolizers or following acute overdose. Monitoring of the drug in plasma or serum is generally accomplished using chromatographic methods. Chiral techniques are available to distinguish escitalopram from its racemate, citalopram.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

| Site | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 0.8-1.1 |

| NET | 7,800 |

| DAT | 27,400 |

| 5-HT1A | >1,000 |

| 5-HT2A | >1,000 |

| 5-HT2C | 2,500 |

| α1 | 3,900 |

| α2 | >1,000 |

| D2 | >1,000 |

| H1 | 2,000 |

| mACh | 1,240 |

| hERG | 2,600 (IC50) |

Escitalopram increases intrasynaptic levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin by blocking the reuptake of the neurotransmitter into the presynaptic neuron. Over time, this leads to a downregulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which is associated with an improvement in passive stress tolerance, and delayed downstream increase in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which may contribute to a reduction in negative affective biases.

Of the SSRIs currently available, escitalopram has the highest selectivity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) compared to the norepinephrine transporter (NET), making the side-effect profile relatively mild in comparison to less-selective SSRIs.

Escitalopram is a substrate of P-glycoprotein and hence P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as verapamil and quinidine may improve its blood brain barrier penetrability. In a preclinical study in rats combining escitalopram with a P-glycoprotein inhibitor, its antidepressant-like effects were enhanced.

Interactions

Escitalopram, similarly to other SSRIs, may increase bleed risk with NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, mefenamic acid), antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and garlic supplements due to escitalopram's inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation via blocking serotonin transporters on platelets. Escitalopram inhibits CYP2D6, and hence may increase plasma levels of a number of CYP2D6 substrates such as aripiprazole, risperidone, tramadol, codeine, etc. As escitalopram is only a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6, analgesia from tramadol may not be affected. Escitalopram should be taken with caution when using St. John's wort, ginseng, dextromethorphan (DXM), linezolid, tramadol, and other serotonergic drugs due to the risk of serotonin syndrome. Exposure to escitalopram is increased moderately, by about 50%, when it is taken with omeprazole. The authors of this study suggested that this increase is unlikely to be of clinical concern.

Bupropion has been found to significantly increase citalopram plasma concentration and systemic exposure; as of April 2018 the interaction with escitalopram had not been studied, but some monographs warned of the potential interaction.

Escitalopram can also prolong the QT interval, and hence it is not recommended in patients that are concurrently on other medications that also have the ability to prolong the QT interval. These drugs include antiarrhythmics, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, some antihistamines (astemizole, mizolastine), macrolide and fluoroquinolone antibiotics, some 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (except palonosetron), and some antiretrovirals (ritonavir, saquinavir, lopinavir). As an SSRI, escitalopram should not be given concurrently with MAOIs.

Chemistry

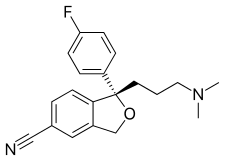

Escitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer (left-handed version) of the racemate citalopram, which is responsible for its name: escitalopram. The (R)-enantiomer (R-citalopram, the right-handed version).

History

Escitalopram was developed in cooperation between Lundbeck and Forest Laboratories. Its development was initiated in 1997, and the resulting new drug application was submitted to the US FDA in March 2001. The short time (3.5 years) it took to develop escitalopram can be attributed to the previous experience of Lundbeck and Forest with citalopram, which has similar pharmacology.

Society and culture

Legal status

The FDA issued the approval of escitalopram for major depression in August 2002, and for generalized anxiety disorder in December 2003. In May 2006, the FDA approved a generic version of escitalopram by Teva. In July 2006, the U.S. District Court of Delaware decided in favor of Lundbeck regarding a patent infringement dispute and ruled the patent on escitalopram valid.

In 2006, Forest Laboratories was granted an 828-day (2 years and 3 months) extension on its US patent for escitalopram. This pushed the patent expiration date from 7 December 2009, to 14 September 2011. Together with the 6-month pediatric exclusivity, the final expiration date was 14 March 2012.

Allegations of illegal marketing

In 2004, separate civil suits alleging illegal marketing of citalopram and escitalopram for use by children and teenagers by Forest were initiated by two whistleblowers: a physician named Joseph Piacentile and a Forest salesman named Christopher Gobble. In February 2009, the suits were joined. Eleven states and the District of Columbia filed notices of intent to intervene as plaintiffs in the action.

The suits alleged that Forest illegally engaged in off-label promotion of Lexapro for use in children; hid the results of a study showing lack of effectiveness in children; paid kickbacks to physicians to induce them to prescribe Lexapro to children; and conducted so-called "seeding studies" that were, in reality, marketing efforts to promote the drug's use by doctors. Forest denied the allegations but ultimately agreed to settle with the plaintiffs for over $313 million.