The Sixth Amendment guarantees criminal defendants nine different rights, including the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury consisting of jurors from the state and district in which the crime was alleged to have been committed. Under the impartial jury requirement, jurors must be unbiased, and the jury must consist of a representative cross-section of the community. The right to a jury applies only to offenses in which the penalty is imprisonment for longer than six months. In Barker v. Wingo, the Supreme Court articulated a balancing test to determine whether a defendant's right to a speedy trial had been violated. It has additionally held that the requirement of a public trial is not absolute and that both the government and the defendant can in some cases request a closed trial.

The Sixth Amendment requires that criminal defendants be given notice of the nature and cause of accusations against them. The amendment's Confrontation Clause gives criminal defendants the right to confront and cross-examine witnesses, while the Compulsory Process Clause gives criminal defendants the right to call their own witnesses and, in some cases, compel witnesses to testify. The Assistance of Counsel Clause grants criminal defendants the right to be assisted by counsel. In Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) and subsequent cases, the Supreme Court held that a public defender must be provided to criminal defendants unable to afford an attorney in all trials where the defendant faces the possibility of imprisonment. The Supreme Court has incorporated (protected at the state level) all Sixth Amendment protections except one: having a jury trial in the same state and district that the crime was committed.

Text

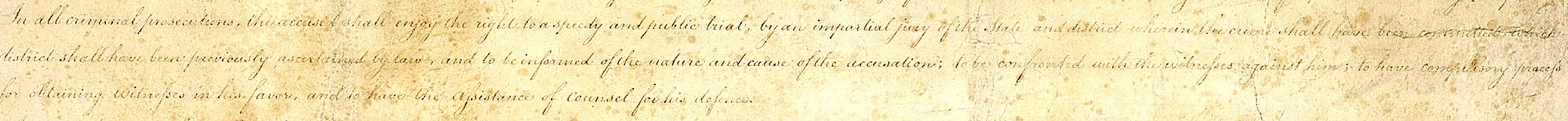

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Rights secured

Speedy trial

Criminal defendants have the right to a speedy trial. In Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514 (1972), the Supreme Court laid down a four-part case-by-case balancing test for determining whether the defendant's speedy trial right has been violated. The four factors are:

- Length of delay. The Court did not explicitly rule that any absolute time limit applies. However, it gave the example that the delay for "ordinary street crime is considerably less than for a serious, complex conspiracy charge."

- Reason for the delay. The prosecution may not excessively delay the trial for its own advantage, but a trial may be delayed to secure the presence of an absent witness or other practical considerations (e.g., change of venue).

- Time and manner in which the defendant has asserted his right. If a defendant agrees to the delay when it works to his own benefit, he cannot later claim he has been unduly delayed.

- Degree of prejudice to the defendant which the delay has caused.

In Strunk v. United States, 412 U.S. 434 (1973), the Supreme Court ruled that if the reviewing court finds that a defendant's right to a speedy trial was violated, then the indictment must be dismissed and any conviction overturned. The Court held that, since the delayed trial is the state action which violates the defendant's rights, no other remedy would be appropriate. Thus, a reversal or dismissal of a criminal case on speedy trial grounds means no further prosecution for the alleged offense can take place.

Public trial

In Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966), the Supreme Court ruled that the right to a public trial is not absolute. In cases where excess publicity would serve to undermine the defendant's right to due process, limitations can be put on public access to the proceedings. According to Press-Enterprise Co. v. Superior Court, 478 U.S. 1 (1986), trials can be closed at the behest of the government if there is "an overriding interest based on findings that closure is essential to preserve higher values and is narrowly tailored to serve that interest". The accused may also request a closure of the trial; though, it must be demonstrated that "first, there is a substantial probability that the defendant's right to a fair trial will be prejudiced by publicity that closure would prevent, and second, reasonable alternatives to closure cannot adequately protect the defendant's right to a fair trial."

Impartial jury

The right to a jury has always depended on the nature of the offense with which the defendant is charged. Petty offenses—those punishable by imprisonment for no more than six months—are not covered by the jury requirement. Even where multiple petty offenses are concerned, the total time of imprisonment possibly exceeding six months, the right to a jury trial does not exist. Also, in the United States, except for serious offenses (such as murder), minors are usually tried in a juvenile court, which lessens the sentence allowed, but forfeits the right to a jury.

Originally, the Supreme Court held that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial indicated a right to "a trial by jury as understood and applied at common law, and includes all the essential elements as they were recognized in this country and England when the Constitution was adopted." Therefore, it was held that federal criminal juries had to be composed of twelve persons and that verdicts had to be unanimous, as was customary in England.

When, under the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court extended the right to a trial by jury to defendants in state courts, it re-examined some of the standards. It has been held that twelve came to be the number of jurors by "historical accident", and that a jury of six would be sufficient, but anything less would deprive the defendant of a right to trial by jury. In Ramos v. Louisiana (2020), the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment mandates unanimity in all federal and state criminal jury trials.

Impartiality

The Sixth Amendment requires juries to be impartial. Impartiality has been interpreted as requiring individual jurors to be unbiased. At voir dire, each side may question potential jurors to determine any bias, and challenge them if the same is found; the court determines the validity of these challenges for cause. Defendants may not challenge a conviction because a challenge for cause was denied incorrectly if they had the opportunity to use peremptory challenges.

In Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado (2017), the Supreme Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment requires a court in a criminal trial to investigate whether a jury's guilty verdict was based on racial bias. For a guilty verdict to be set aside based on the racial bias of a juror, the defendant must prove that the racial bias "was a significant motivating factor in the juror's vote to convict".

Venire of juries

Another factor in determining the impartiality of the jury is the nature of the panel, or venire, from which the jurors are selected. Venires must represent a fair cross-section of the community; the defendant might establish that the requirement was violated by showing that the allegedly excluded group is a "distinctive" one in the community, that the representation of such a group in venires is unreasonable and unfair in regard to the number of persons belonging to such a group, and that the under-representation is caused by a systematic exclusion in the selection process. Thus, in Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975), the Supreme Court invalidated a state law that exempted women who had not made a declaration of willingness to serve from jury service, while not doing the same for men.

Sentencing

In Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000), and Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 (2004), the Supreme Court ruled that a criminal defendant has a right to a jury trial not only on the question of guilt or innocence, but also regarding any fact used to increase the defendant's sentence beyond the maximum otherwise allowed by statutes or sentencing guidelines. In Alleyne v. United States, 570 U.S. 99 (2013), the Court expanded on Apprendi and Blakely by ruling that a defendant's right to a jury applies to any fact that would increase a defendant's sentence beyond the minimum otherwise required by statute. In United States v. Haymond, 588 U.S. ___ (2019), the Court decided a jury is required if a federal supervised release revocation would carry a mandatory minimum prison sentence.

Vicinage

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution requires defendants be tried by juries and in the state in which the crime was committed. The Sixth Amendment requires the jury to be selected from judicial districts ascertained by statute. In Beavers v. Henkel, 194 U.S. 73 (1904), the Supreme Court ruled that the place where the offense is charged to have occurred determines a trial's location. Where multiple districts are alleged to have been locations of the crime, any of them may be chosen for the trial. In cases of offenses not committed in any state (for example, offenses committed at sea), the place of trial may be determined by the Congress. Unlike other Sixth Amendment guarantees, the Court has not incorporated the vicinage right.

Notice of accusation

A criminal defendant has the right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation against them. Therefore, an indictment must allege all the ingredients of the crime to such a degree of precision that it would allow the accused to assert double jeopardy if the same charges are brought up in subsequent prosecution. The Supreme Court held in United States v. Carll, 105 U.S. 611 (1881), that "in an indictment ... it is not sufficient to set forth the offense in the words of the statute, unless those words of themselves fully, directly, and expressly, without any uncertainty or ambiguity, set forth all the elements necessary to constitute the offense intended to be punished." Vague wording, even if taken directly from a statute, does not suffice. However, the government is not required to hand over written copies of the indictment free of charge.

Confrontation

The Confrontation Clause relates to the common law rule preventing the admission of hearsay, that is to say, testimony by one witness as to the statements and observations of another person to prove that the statement or observation was true. The rationale was that the defendant had no opportunity to challenge the credibility of and cross-examine the person making the statements. Certain exceptions to the hearsay rule have been permitted; for instance, admissions by the defendant are admissible, as are dying declarations. Nevertheless, in California v. Green, 399 U.S. 149 (1970), the Supreme Court has held that the hearsay rule is not the same as the Confrontation Clause. Hearsay is admissible under certain circumstances. For example, in Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123 (1968), the Supreme Court ruled that while a defendant's out of court statements were admissible in proving the defendant's guilt, they were inadmissible hearsay against another defendant. Hearsay may, in some circumstances, be admitted though it is not covered by one of the long-recognized exceptions. For example, prior testimony may sometimes be admitted if the witness is unavailable. However, in Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36 (2004), the Supreme Court increased the scope of the Confrontation Clause by ruling that "testimonial" out-of-court statements are inadmissible if the accused did not have the opportunity to cross-examine that accuser and that accuser is unavailable at trial. In Davis v. Washington 547 U.S. 813 (2006), the Court ruled that "testimonial" refers to any statement that an objectively reasonable person in the declarant's situation would believe likely to be used in court. In Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, 557 U.S. 305 (2009), and Bullcoming v. New Mexico, 564 U.S. 647 (2011), the Court ruled that admitting a lab chemist's analysis into evidence, without having him testify, violated the Confrontation Clause.[15][16] In Michigan v. Bryant, 562 U.S. 344 (2011), the Court ruled that the "primary purpose" of a shooting victim's statement as to who shot him, and the police's reason for questioning him, each had to be objectively determined. If the "primary purpose" was for dealing with an "ongoing emergency", then any such statement was not testimonial and so the Confrontation Clause would not require the person making that statement to testify in order for that statement to be admitted into evidence. The right to confront and cross-examine witnesses also applies to physical evidence; the prosecution must present physical evidence to the jury, providing the defense ample opportunity to cross-examine its validity and meaning. Prosecution generally may not refer to evidence without first presenting it. In Hemphill v. New York, No. 20-637, 595 U.S. ___ (2022), the Court ruled the accused had to be given an opportunity to cross-examine a witness called to rebut the accused's defense, even if the trial judge rules that defense to be misleading.

In the late 20th and early 21st century this clause became an issue in the use of the silent witness rule.

Compulsory process

The Compulsory Process Clause gives any criminal defendant the right to call witnesses in his favor. If any such witness refuses to testify, that witness may be compelled to do so by the court at the request of the defendant. However, in some cases the court may refuse to permit a defense witness to testify. For example, if a defense lawyer fails to notify the prosecution of the identity of a witness to gain a tactical advantage, that witness may be precluded from testifying.

Assistance of counsel

A criminal defendant has the right to be assisted by counsel.

In Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932), the Supreme Court ruled that "in a capital case, where the defendant is unable to employ counsel, and is incapable adequately of making his own defense because of ignorance, feeble mindedness, illiteracy, or the like, it is the duty of the court, whether requested or not, to assign counsel for him." In Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938), the Supreme Court ruled that in all federal cases, counsel would have to be appointed for defendants who were too poor to hire their own.

In 1961, the Court extended the rule that applied in federal courts to state courts. It held in Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U.S. 52 (1961), that counsel had to be provided at no expense to defendants in capital cases when they so requested, even if there was no "ignorance, feeble mindedness, illiteracy, or the like". Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), ruled that counsel must be provided to indigent defendants in all felony cases, overruling Betts v. Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942), in which the Court ruled that state courts had to appoint counsel only when the defendant demonstrated "special circumstances" requiring the assistance of counsel. Under Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972), counsel must be appointed in any case resulting in a sentence of actual imprisonment. Regarding sentences not immediately leading to imprisonment, the Court in Scott v. Illinois, 440 U.S. 367 (1979), ruled that counsel did not need to be appointed, but in Alabama v. Shelton, 535 U.S. 654 (2002), the Court held that a suspended sentence that may result in incarceration cannot be imposed if the defendant did not have counsel at trial.

As stated in Brewer v. Williams, 430 U.S. 387 (1977), the right to counsel "[means] at least that a person is entitled to the help of a lawyer at or after the time that judicial proceedings have been initiated against him, whether by formal charge, preliminary hearing, indictment, information, or arraignment." Brewer goes on to conclude that once adversary proceedings have begun against a defendant, he has a right to legal assistance when the government interrogates him and that when a defendant is arrested, "arraigned on [an arrest] warrant before a judge", and "committed by the court to confinement", "[t]here can be no doubt that judicial proceedings ha[ve] been initiated."

Self-representation

A criminal defendant may represent himself, unless a court deems the defendant to be incompetent to waive the right to counsel.

In Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806 (1975), the Supreme Court recognized a defendant's right to pro se representation. However, under Godinez v. Moran, 509 U.S. 389 (1993), a court that believes the defendant is less than fully competent to represent himself can require that defendant to be assisted by counsel. In Martinez v. Court of Appeal of California, 528 U.S. 152 (2000), the Supreme Court ruled the right to pro se representation did not apply to appellate courts. In Indiana v. Edwards, 554 U.S. 164 (2008), the Court ruled that a criminal defendant could be simultaneously competent to stand trial, but not competent to represent himself.

In Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817 (1977), the Supreme Court held that the constitutional right of "meaningful access to the courts" can be satisfied by counsel or access to legal materials. Bounds has been interpreted by several United States courts of appeals to mean a pro se defendant does not have a constitutional right to access a prison law library to research his defense when access to the courts has been provided through appointed counsel.