New Urbanism is an urban design movement which promotes environmentally friendly habits by creating walkable neighborhoods containing a wide range of housing and job types. It arose in the United States in the early 1980s, and has gradually influenced many aspects of real estate development, urban planning, and municipal land-use strategies.

New Urbanism is strongly influenced by urban design practices that were prominent until the rise of the automobile prior to World War II; it encompasses ten basic principles such as traditional neighborhood design (TND) and transit-oriented development (TOD). These ideas can all be circled back to two concepts: building a sense of community and the development of ecological practices.

Market Street, Celebration, Florida

The organizing body for New Urbanism is the Congress for the New Urbanism, founded in 1993. Its foundational text is the Charter of the New Urbanism, which begins:

We advocate the restructuring of public policy and development practices to support the following principles: neighborhoods should be diverse in use and population; communities should be designed for the pedestrian and transit as well as the car; cities and towns should be shaped by physically defined and universally accessible public spaces and community institutions; urban places should be framed by architecture and landscape design that celebrate local history, climate, ecology, and building practice.

New Urbanists support: regional planning for open space; context-appropriate architecture and planning; adequate provision of infrastructure such as sporting facilities, libraries and community centres;[5]

and the balanced development of jobs and housing. They believe their

strategies can reduce traffic congestion by encouraging the population

to ride bikes, walk, or take the train. They also hope that this set up

will increase the supply of affordable housing and rein in suburban sprawl. The Charter of the New Urbanism also covers issues such as historic preservation, safe streets, green building, and the re-development of brownfield land. The ten Principles of Intelligent Urbanism also phrase guidelines for new urbanist approaches.

Architecturally, new urbanist developments are often accompanied by New Classical, postmodern, or vernacular styles, although that is not always the case.

Background

New Broad Street, Baldwin Park, Florida

Until the mid 20th century, cities were generally organized into and

developed around mixed-use walkable neighborhoods. For most of human

history this meant a city that was entirely walkable, although with the

development of mass transit the reach of the city extended outward along transit lines, allowing for the growth of new pedestrian communities such as streetcar suburbs.

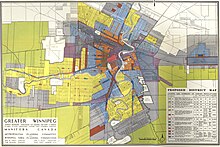

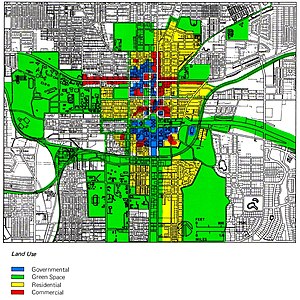

But with the advent of cheap automobiles and favorable government

policies, attention began to shift away from cities and towards ways of

growth more focused on the needs of the car. Specifically, after World War II urban planning largely centered around the use of municipal zoning

ordinances to segregate residential from commercial and industrial

development, and focused on the construction of low-density

single-family detached houses as the preferred housing format for the

growing middle class.

The physical separation of where people live from where they work, shop

and frequently spend their recreational time, together with low housing

density, which often drastically reduced population density relative to

historical norms, made automobiles indispensable for practical

transportation and contributed to the emergence of a culture of automobile dependency.

Beach Drive, St. Petersburg, Florida

This new system of development, with its rigorous separation of uses, arose after World War II and became known as "conventional suburban development" or pejoratively as urban sprawl. The majority of U.S. citizens now live in suburban communities built in the last fifty years, and automobile use per capita has soared.

Celebration, FL Post Office, designed by architect Michael Graves

Although New Urbanism as an organized movement would only arise

later, a number of activists and thinkers soon began to criticize the modernist planning techniques being put into practice. Social philosopher and historian Lewis Mumford criticized the "anti-urban" development of post-war America. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, written by Jane Jacobs

in the early 1960s, called for planners to reconsider the single-use

housing projects, large car-dependent thoroughfares, and segregated

commercial centers that had become the "norm". The French architect François Spoerry has developed in the 60's the concept of "soft architecture" that he applied to Port Grimaud,

a new marina in south of France. The success of this project had a

considerable influence and led to many new projects of soft architecture

like Port Liberté in New Jersey or Le Plessis Robisson in France.

Rooted in these early dissenters, the ideas behind New Urbanism

began to solidify in the 1970s and 80s with the urban visions and

theoretical models for the reconstruction of the "European" city

proposed by architect Leon Krier, and the pattern language theories of Christopher Alexander. The term "new urbanism" itself started being used in this context in the mid-1980s, but it wasn't until the early 1990s that it was commonly written as a proper noun capitalized.

In 1991, the Local Government Commission, a private nonprofit group in Sacramento, California, invited architects Peter Calthorpe, Michael Corbett, Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Moule, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Stefanos Polyzoides, and Daniel Solomon to develop a set of community principles for land use planning. Named the Ahwahnee Principles (after Yosemite National Park's Ahwahnee Hotel),

the commission presented the principles to about one hundred government

officials in the fall of 1991, at its first Yosemite Conference for

Local Elected Officials.

Calthorpe, Duany, Moule, Plater-Zyberk, Polyzoides, and Solomon

founded the Chicago-based Congress for the New Urbanism in 1993. The CNU

has grown to more than three thousand members, and is the leading

international organization promoting New Urbanist design principles. It

holds annual Congresses in various U.S. cities.

In 2009, co-founders Elizabeth Moule, Hank Dittmar, and Stefanos

Polyzoides authored the Canons of Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism

to clarify and detail the relationship between New Urbanism and

sustainability. The Canons are "a set of operating principles for human

settlement that reestablish the relationship between the art of

building, the making of community, and the conservation of our natural

world". They promote the use of passive heating and cooling solutions,

the use of locally obtained materials, and in general, a "culture of

permanence".

New Urbanism is a broad movement that spans a number of different

disciplines and geographic scales. And while the conventional approach

to growth remains dominant, New Urbanist principles have become

increasingly influential in the fields of planning, architecture, and

public policy.

Defining elements

Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk,

two of the founders of the Congress for the New Urbanism, observed

mixed-use streetscapes with corner shops, front porches, and a diversity

of well-crafted housing while living in one of the Victorian neighborhoods of New Haven, Connecticut. They and their colleagues observed patterns including the following:

A park in Celebration, Florida

Great King St, New Town, Edinburgh

- The neighborhood has a discernible center. This is often a square or a green and sometimes a busy or memorable street corner. A transit stop would be located at this center.

- Most of the dwellings are within a five-minute walk of the center, an average of roughly 0.25 miles (0.40 km).

- There are a variety of dwelling types — usually houses, rowhouses, and apartments — so that younger and older people, singles and families, the poor and the wealthy may find places to live.

- At the edge of the neighborhood, there are shops and offices of sufficiently varied types to supply the weekly needs of a household.

- A small ancillary building or garage apartment is permitted within the backyard of each house. It may be used as a rental unit or place to work (for example, an office or craft workshop).

- An elementary school is close enough so that most children can walk from their home.

- There are small playgrounds accessible to every dwelling — not more than a tenth of a mile away.

- Streets within the neighborhood form a connected network, which disperses traffic by providing a variety of pedestrian and vehicular routes to any destination.

- The streets are relatively narrow and shaded by rows of trees. This slows traffic, creating an environment suitable for pedestrians and bicycles.

- Buildings in the neighborhood center are placed close to the street, creating a well-defined outdoor room.

- Parking lots and garage doors rarely front the street. Parking is relegated to the rear of buildings, usually accessed by alleys.

- Certain prominent sites at the termination of street vistas or in the neighborhood center are reserved for civic buildings. These provide sites for community meetings, education, and religious or cultural activities.

Terminology

A Mediterranean Revival house in Celebration, Florida

Several terms are viewed either as synonymous, included in, or

overlapping with the New Urbanism. The terms Neotraditional Development

or Traditional Neighborhood Development are often associated with the

New Urbanism. These terms generally refer to complete New Towns or new

neighborhoods, often built in traditional architectural styles, as

opposed to smaller infill and redevelopment projects. The term

Traditional Urbanism has also been used to describe the New Urbanism by

those who object to the "new" moniker. The term "Walkable Urbanism" was

proposed as an alternative term by developer and professor Christopher

Leinberger. Many debate whether Smart Growth

and the New Urbanism are the same or whether substantive differences

exist between the two; overlap exists in membership and content between

the two movements. Placemaking is another term that is often used to

signify New Urbanist efforts or those of like-minded groups. The term

Transit-Oriented Development is sometimes cited as being coined by

prominent New Urbanist Peter Calthorpe and is heavily promoted by New Urbanists. The term Sustainable development

is sometimes associated with the New Urbanism as there has been an

increasing focus on the environmental benefits of New Urbanism

associated with the rise of the term sustainability in the 2000s,

however, this has caused some confusion as the term is also used by the United Nations and Agenda 21 to include human development issues (e.g., developing country) that exceed the scope of land development intended to be addressed by the New Urbanism or Sustainable Urbanism. The term "livability" or "livable communities" was popular under the Obama administration, though it dates back at least to the mid-1990s when the term was used by the Local Government Commission.

A Key West style house in Baldwin Park, Florida

Planning magazine discussed the proliferation of "urbanisms" in an

article in 2011 titled "A Short Guide to 60 of the Newest Urbanisms". Several New Urbanists have popularized terminology under the umbrella of the New Urbanism including Sustainable Urbanism and Tactical Urbanism

(of which Guerrilla Urbanism can be viewed as a subset). The term

Tactical Urbanism was coined by Frenchman Michel de Certau in 1968 and

revived in 2011 by New Urbanist Mike Lydon and the co-authors of the

Tactical Urbanism Guide. In 2011 Andres Duany authored a book that used the term Agrarian Urbanism to describe an agriculturally-focused subset of New Urbanist town design. In 2013 a group of New Urbanists led by CNU co-founder Andres Duany began a research project under the banner of Lean Urbanism which purported to provide a bridge between Tactical Urbanism and the New Urbanism.

Other terms have surfaced in reaction to the New Urbanism

intended to provide a contrast, alternative to, or a refinement of the

New Urbanism. Some of these terms include Everyday Urbanism by Harvard

Professor Margaret Crawford, John Chase, and John Kaliski, Ecological Urbanism, and True Urbanism by architect Bernard Zyscovich. Landscape urbanism

was popularized by Charles Waldheim who explicitly defined it as in

opposition to the New Urbanism in his lectures at Harvard University. Landscape Urbanism and its Discontents, edited by Andres Duany and Emily Talen, specifically addressed the tension between these two views of urbanism. Michael E. Arth promotes what he describes as a variant of the New Urbanism called the New Pedestrianism, which is intended to be more pedestrian-oriented and traces its origins to a 1929 planned community in Radburn, New Jersey.

Organizations

The primary organization promoting the New Urbanism in the United States is the Congress for the New Urbanism

(CNU). The Congress for the New Urbanism is the leading organization

promoting walkable, mixed-use neighborhood development, sustainable

communities and healthier living conditions. CNU members promote the

principles of CNU's Charter and the hallmarks of New Urbanism,

including:

- Livable streets arranged in compact, walkable blocks.

- A range of housing choices to serve people of diverse ages and income levels.

- Schools, stores and other nearby destinations reachable by walking, bicycling or transit service.

- An affirming, human-scaled public realm where appropriately designed buildings define and enliven streets and other public spaces.

The CNU has met annually since 1993 when they held their first general meeting in Alexandria, Virginia,

with approximately one hundred attendees. By 2008 the Congress was

drawing two to three thousand attendees to the annual meetings.

The CNU began forming local and regional chapters circa 2004 with the founding of the New England and Florida Chapters. By 2011 there were 16 official chapters and interest groups for 7 more. As of 2013,

Canada hosts two full CNU Chapters, one in Ontario (CNU Ontario), and

one in British Columbia (Cascadia) which also includes a portion of the

north-west US states.

While the CNU has international participation in Canada, sister

organizations have been formed in other areas of the world including the

Council for European Urbanism (CEU), the Movement for Israeli Urbanism (MIU) and the Australian Council for the New Urbanism.

By 2002 chapters of Students for the New Urbanism began appearing at universities including the Savannah College of Art and Design, University of Georgia, University of Notre Dame, and the University of Miami.

In 2003, a group of younger professionals and students met at the 11th

Congress in Washington, D.C. and began developing a "Manifesto of the

Next Generation of New Urbanists". The Next Generation of New Urbanists

held their first major session the following year at the 12th meeting

of the CNU in Chicago in 2004. The group has continued meeting annually

as of 2014 with a focus on young professionals, students, new member

issues, and ensuring the flow of fresh ideas and diverse viewpoints

within the New Urbanism and the CNU. Spinoff projects of the Next

Generation of the New Urbanists include the Living Urbanism publication

first published in 2008 and the first Tactical Urbanism Guide.

The CNU has spawned publications and research groups. Publications include the New Urban News and the New Town Paper.

Research groups have formed independent nonprofits to research

individual topics such as the Form-Based Codes Institute, The National

Charrette Institute and the Center for Applied Transect Studies.

In the United Kingdom New Urbanist and European urbanism principles are practised and taught by The Prince's Foundation for the Built Environment.

Around the world, other organisations promote New Urbanism as part of their remit, such as INTBAU, A Vision of Europe, Council for European Urbanism, and others.

The CNU and other national organizations have also formed

partnerships with like-minded groups. Organizations under the banner of Smart Growth

also often work with the Congress for the New Urbanism. In addition the

CNU has formed partnerships on specific projects such as working with

the United States Green Building Council and the Natural Resources Defense Council to develop the LEED for Neighborhood Development standards, and with the Institute of Transportation Engineers to develop a Context Sensitive Solutions (CSS) Design manual.

Film

The New Urbanism Film Festival

was held in 2013 and 2014 in Los Angeles to highlight films and short

films about the New Urbanism and related topics. The 2011 film Urbanized by Gary Hustwit featured then CNU Board Chair Ellen Dunham-Jones and other urban thinkers on the international story of urbanization including the New Urbanist efforts in the United States.

The 2004 documentary The End of Suburbia: Oil Depletion and the Collapse of the American Dream argues that the depletion of oil will result in the demise of the sprawl-type development. New Urban Cowboy: Toward a New Pedestrianism, a feature length 2008 documentary about urban designer Michael E. Arth, explains the principles of his New Pedestrianism, a more ecological and pedestrian-oriented version of New Urbanism.

The film also gives a brief history of New Urbanism, and chronicles

the rebuilding of an inner city slum into a model of New Pedestrianism

and New Urbanism called The Garden District.

Criticism

New Urbanism has drawn both praise and criticism from all parts of the political spectrum. It has been criticized both for being a social engineering

scheme and for failing to address social equity and for both

restricting private enterprise and for being a deregulatory force in

support of private sector developers.

Journalist Alex Marshall

has decried New Urbanism as essentially a marketing scheme that

repackages conventional suburban sprawl behind a façade of nostalgic

imagery and empty, aspirational slogans. In a 1996 article in Metropolis Magazine, Marshall denounced New Urbanism as "a grand fraud". The attack continued in numerous articles, including an opinion column in the Washington Post in September of the same year, and in Marshall's first book, How Cities Work: Suburbs, Sprawl, and the Roads Not Taken.

Critics have asserted that the effectiveness claimed for the New

Urbanist solution of mixed income developments lacks statistical

evidence. Independent studies have supported the idea of addressing poverty through mixed-income developments, but the argument that New Urbanism produces such diversity has been challenged from findings from one community in Canada.

Some parties have criticized the New Urbanism for being too

accommodating of motor vehicles and not going far enough to promote

walking, cycling, and public transport. The Charter of the New Urbanism

states that "communities should be designed for the pedestrian and

transit as well as the car". Some critics suggest that communities should exclude the car altogether in favor of car-free developments. Michael E Arth proposes new pedestrianism

as a way to further elevate the status of pedestrians by focusing on

pedestrian-only paths. Steve Melia proposes the idea of "filtered

permeability"

which increases the connectivity of the pedestrian and cycling network

resulting in a time and convenience advantage over drivers while still

limiting the connectivity of the vehicular network and thus maintaining

the safety benefits of cul de sacs and horseshoe loops in resistance to

property crime.

In response to critiques of a lack of evidence for the New

Urbanism's claimed environmental benefits, a rating system for

neighborhood environmental design, LEED-ND, was developed by the U.S. Green Building Council, Natural Resources Defense Council, and the Congress for the New Urbanism, to quantify the sustainability of New Urbanist neighborhood design. New Urbanist and board member of CNU, Doug Farr has taken a step further and coined Sustainable Urbanism,

which combines New Urbanism and LEED-ND to create walkable,

transit-served urbanism with high performance buildings and

infrastructure.

Criticizing the lack of evidence for low greenhouse gas emissions results, Susan Subak

has pointed out that while New Urbanism emphasizes walkability and

building variety, it is the scale of dwellings, especially the absence

of large houses that may determine successful, low carbon outcomes at

the community level.

New Urbanism has been criticized for being a form of centrally

planned, large-scale development, "instead of allowing the initiative

for construction to be taken by the final users themselves". It has been criticized for asserting universal principles of design instead of attending to local conditions.

Examples

United States

New

Urbanism is having a growing influence on how and where metropolitan

regions choose to grow. At least fourteen large-scale planning

initiatives are based on the principles of linking transportation and

land-use policies, and using the neighborhood as the fundamental

building block of a region. Miami, Florida, has adopted the most ambitious New Urbanist-based zoning code reform yet undertaken by a major U.S. city.

More than six hundred new towns, villages, and neighborhoods,

following New Urbanist principles, have been planned or are currently

under construction in the U.S. Hundreds of new, small-scale, urban and

suburban infill projects are under way to reestablish walkable streets

and blocks. In Maryland and several other states, New Urbanist

principles are an integral part of smart growth legislation.

In the mid-1990s, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD) adopted the principles of the New Urbanism in its

multibillion-dollar program to rebuild public housing projects

nationwide. New Urbanists have planned and developed hundreds of

projects in infill locations. Most were driven by the private sector,

but many, including HUD projects, used public money.

University Place in Memphis

In 2010 University Place in Memphis became the second only U.S. Green Building Council

(USGBC) LEED certified neighborhood. LEED ND (neighborhood

development) standards integrates principles of smart growth, urbanism

and green building and were developed through a collaboration between

USGBC, Congress for the New Urbanism, and the Natural Resources Defense Council. University Place, developed by McCormack Baron Salazar, is a 405-unit, 30-acre, mixed-income, mixed use, multigenerational, HOPE VI grant community that revitalized the severely distressed Lamar Terrace public housing site.

The Cotton District

The Cotton District in Starkville, Mississippi, was the first New Urbanist development, begun in 1968 long before the New Urbanism movement was organized.

The District borders Mississippi State University, and consists mostly

of residential rental units for college students along with restaurants,

bars and retail. The Cotton District got its name because it is built

in the vicinity of an old cotton mill.

Seaside

Seaside, Florida, the first fully New Urbanist town, began development in 1981 on eighty acres (324,000 m²) of Florida Panhandle coastline. It was featured on the cover of the Atlantic Monthly

in 1988, when only a few streets were completed, and has become

internationally famous for its architecture, and the quality of its

streets and public spaces.

Seaside is now a tourist destination and appeared in the 1998 movie The Truman Show.

Lots sold for $15,000 in the early 1980s, and slightly over a decade

later, the price had escalated to about $200,000. Today, most lots sell

for more than a million dollars, and some houses top $5 million.

Mueller Community

The Mueller Community is located on the 700 acre site of the former Robert Mueller Municipal Airport in Austin, Texas,

which closed in 1999. Per the developer, the value of the Mueller

development upon completion will be $1.3 billion, and will comprise 4.2

million square feet of non-residential development, 650,000 square feet

of retail space, 4,600 homes, and 140 acres of open space. An estimated

10,000 permanent jobs within the development will have been created by

the time it is complete. The Mueller Community also has more electric

cars per capita than any other neighborhood in the United States – a

fact partially attributable to an incentive program.

Stapleton

The site of the former Stapleton International Airport in Denver and Aurora, Colorado, closed in 1995, is now being redeveloped by Forest City Enterprises.

Stapleton is expected to be home to at least 30,000 residents, six

schools and 2 million square feet (180,000 m²) of retail. Construction

began in 2001. Northfield Stapleton, one of the development's major retail centers, recently opened.

San Antonio

In 1997 San Antonio, Texas,

as part of a new master plan, created new regulations called the

Unified Development Code (UDC), largely influenced by New Urbanism. One

feature of the UDC is six unique land development patterns that can be

applied to certain districts: Conservation Development, Commercial

Center Development, Office or Institutional Campus Development,

Commercial Retrofit Development, Tradition Neighborhood Development, Transit Oriented Development.

Each district has specific standards and design regulation. The six

development patterns were created to reflect existing development

patterns.

Mountain House

Mountain House, one of the latest New Urbanist projects in the United States, is a new town located near Tracy, California.

Construction started in 2001. Mountain House will consist of 12

villages, each with its own elementary school, park, and commercial

area. In addition, a future train station, transit center and bus system are planned for Mountain House.

Mesa del Sol

Mesa del Sol, New Mexico—the largest New Urbanist project in the United States—was designed by architect Peter Calthorpe, and is being developed by Forest City Enterprises.

Mesa del Sol may take five decades to reach full build-out, at which

time it should have 38,000 residential units, housing a population of

100,000; a 1,400-acre (5.7 km2) industrial office park; four town centers; an urban center; and a downtown that would provide a twin city within Albuquerque.

I'On

Located in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, I'On

is a traditional neighborhood development, mixed with a new urbanism

styled architecture, reflecting on the building designs of the nearby

downtown areas of Charleston, South Carolina. Founded on April 30, 1995, I'On was designed by the town planning firms of Dover, Kohl & Partners and Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company, and currently holds over 750 single family homes. Features of the community include extensive sidewalks, shared public greens and parks, trails and a grid of narrow, traffic calming streets. Most homes are required to have a front porch

of not less than eight feet (2.46 m) in depth. Floor heights of 10 feet

(3.1 m), raised foundations and smaller lot sizes give the community a dense, vertical feel.

Haile Plantation

Haile Plantation, Florida, is a 2,600 household (1,700 acres (6.9 km2))

development of regional impact southwest of the city of Gainesville,

within Alachua County. Haile Village Center is a traditional

neighborhood center within the development. It was originally started in

1978 and completed in 2007. In addition to the 2,600 homes the

neighborhood consists of two merchant centers (one a New England narrow

street village and the other a chain grocery strip mall). There are also

two public elementary schools and an 18-hole golf course.

Celebration, Florida

In June 1996, the Walt Disney Company unveiled its 5,000 acre (20 km²) town of Celebration,

near Orlando, Florida. Celebration opened its downtown in October 1996,

relying heavily on the experiences of Seaside, whose downtown was

nearly complete. Disney shuns the label New Urbanism, calling

Celebration simply a "town".

Celebration's Downtown has become one of the area's most popular

tourist destinations making the community a showcase for New Urbanism as

a prime example of the creation of a "sense of place".

Jersey City

The construction of the Hudson Bergen Light Rail in Hudson County, New Jersey has spurred transit-oriented development. In Jersey City, two projects are planned to transform brownfield sites, both of which have required remediation of toxic waste by previous owners. Bayfront, once site of a Honeywell plant is a 100 acres (0.40 km2) site on the Hackensack River, and is nearby the planned West Campus of New Jersey City University. Canal Crossing, named for the former Morris Canal, was once partially owned by PPG Industries, and is a 117 acres (0.47 km2) site west of Liberty State Park.

Old York Village, Chesterfield Township, New Jersey

The sparsely developed agricultural Township of Chesterfield in New Jersey covers approximately 21.61 square miles (56.0 km2)

and has made farmland preservation a priority since the 1970s.

Chesterfield has permanently preserved more than 7,000 acres (28 km2)

of farmland through state and county programs and a township-wide

transfer of development credits program that directs future growth to a

designated "receiving area" known as Old York Village. Old York Village

is a neo-traditional, new urbanism town on 560 acres (2.3 km2)

incorporating a variety of housing types, neighborhood commercial

facilities, a new elementary school, civic uses, and active and passive

open space areas with preserved agricultural land surrounding the

planned village. Construction began in the early 2000s and a

significant percentage of the community is now complete. Old York

Village was the winner of the American Planning Association National

Outstanding Planning Award in 2004.

Civita

Civita is a sustainable, transit-oriented 230-acre master-planned village under development in the Mission Valley area of San Diego, California, United States. Located on a former quarry site, the urban-style village is organized around a 19-acre community park that cascades down the terraced property. Civita development plans call for 60 to 70 acres of parks and open space, 4,780 residences (including approximately 478 affordable units), an approximately 480,000-square-foot retail center, and 420,000 square feet for an office/business campus.

Sudberry Properties, the developer of Civita, incorporated numerous green building practices in the Civita design. In 2009, Civita achieved a Stage 1 Gold rating for the U.S. Green Building Council’s

2009 LEED-ND (Neighborhood Development) pilot and received the

California Governor’s Environmental and Economic Leadership Award. In 2010, Civita was designated as a California Catalyst Community by the California Department of Housing and Community Development

to support innovation and test sustainable strategies that reflect the

interdependence of environmental, economic, and community health.

Del Mar Station

Del Mar (Los Angeles Metro station), which won a Congress for the New Urbanism Charter Award in 2003, is a transit-oriented development

surrounding a prominent Metro Rail stop on the Gold Line, which

connects Los Angeles and Pasadena. Located at the southern edge of

downtown Pasadena, it serves as a gateway to the city with 347

apartments, out of which 15% are affordable units. Approximately 20,000

square feet of retail is linked with a network of public plazas, paseos

and private courtyards. The 3.4-acre, $77 million project sits above a

1,200-car multi-level subterranean parking garage, with 600 spaces

dedicated to transit. The light rail right of way, detailed as a public

street, bisects the site. It was designed by Moule & Polyzoides.

Norfolk VA East Beach

Norfolk,

VA, East Beach. designed and built in the style of traditional Atlantic

coastal villages. The Master Plan for East Beach was developed in the

style of “New Urbanism” by world renowned TND master planners Duany

Plater-Zyberk. Newly constructed homes reflect traditional classic

detail and proportion of Tidewater Virginia homes, and are built with

materials that will withstand the test of time and forces of Mother

Nature and the Chesapeake Bay.

Other countries

New Urbanism is closely related to the Urban village

movement in Europe. They both occurred at similar times and share many

of the same principles although urban villages has an emphasis on

traditional city planning. In Europe many brown-field sites have been

redeveloped since the 1980s following the models of the traditional city

neighbourhoods rather than Modernist models. One well-publicized

example is Poundbury in England, a suburban extension to the town of Dorchester, which was built on land owned by the Duchy of Cornwall under the overview of Prince Charles. The original masterplan was designed by Leon Krier.

A report carried out after the first phase of construction found a high

degree of satisfaction by residents, although the aspirations to reduce

car dependency

had not been successful. Rising house prices and a perceived premium

have made the open market housing unaffordable for many local people.

The Council for European Urbanism (CEU), formed in 2003, shares

many of the same aims as the U.S.'s New Urbanists. CEU's Charter is a

development of the Congress for the New Urbanism

Charter revised and reorganised to relate better to European

conditions. An Australian organisation, Australian Council for New

Urbanism has since 2001 run conferences and events to promote New

Urbanism in that country. A New Zealand Urban Design Protocol was created by the Ministry for the Environment in 2005.

There are many developments around the world that follow New Urbanist principles to a greater or lesser extent:

Europe

- Le Plessis-Robinson, a 21st-century example of neo-traditionalism, in the south-west of Paris. This city is in the process of transforming itself, destroying old modern blocklike buildings and replacing them with traditional buildings and houses in one of the biggest worldwide projects with Val d'Europe. In 2008 the city was nominated best architectural project of the European Union.

- Poundbury, in Dorset, England, is a neotraditionalist urban extension focussed on high quality urban realm and the expression of traditional modes of urban or village life.

- Tornagrain, Between Inverness and Nairn, Scotland, The design is based on the architectural and planning traditions of the Highlands and the rest of Scotland.

- Val d'Europe, east of Paris, France. Developed by Disneyland Resort Paris, this town is a kind of European counterpart to Walt Disney World Celebration City.

- Jakriborg, in Southern Sweden, is a recent example of the New Urbanist movement.

- Brandevoort, in Helmond, in the Netherlands, is a new example of the New Urbanist movement.

- Sankt Eriksområdet quarter in Stockholm, Sweden, built in the 1990s.

- Other developments can be found at Heulebrug, part of Knokke-Heist, in Belgium, and Fonti di Matilde in San Bartolomeo (outside of Reggio Emilia), Italy.

- Kartanonkoski, in Vantaa, Finland, is the only example of neotraditional architecture in Finland implemented on a larger scale. The area has around 4000 inhabitants and its architecture has been mainly influenced by Nordic Classicism.

Americas

- Mahogany Bay Village, Belize, is a 60-acre New Urbanist community on Ambergris Caye, Belize.

- Orchid Bay, Belize, is one of the largest New Urbanist projects in Central America and the Caribbean.

- Las Catalinas, Costa Rica, is a coastal town in the Guanacaste Province of Northwest Costa Rica. Envisioned as a compact, walkable beach town, Las Catalinas was founded in 2006 by Charles Brewer and incorporates many of the principles of New Urbanism.

- McKenzie Towne is a New Urbanist development which commenced in 1995 by Carma Developers LP in Calgary.

- Cornell, within the city of Markham, Ontario, was designed with walkable neighborhoods, density to support public transit, a variety of housing types and retail.

- New Amherst is a new urbanist development in the town of Cobourg, Ontario.

- UniverCity, beside the Simon Fraser University campus on Burnaby Mountain in Burnaby, British Columbia, is an award-winning sustainable community that is designed to be walkable, dense, and well connected to public transit networks.

Asia

- The structure plan for Thimphu, Bhutan, follows Principles of Intelligent Urbanism, which share underlying axioms with the New Urbanism.

Africa

There are several such developments in South Africa. The most notable is Melrose Arch in Johannesburg. Triple Point is a comparable mixed-use development in East London, in Eastern Cape

province. The development, announced in 2007, comprises 30 hectares. It

is made up of three apartment complexes together with over 30

residential sites as well as 20,000 sq m of residential and office

space. The development is valued at over R2 billion ($250 million). There have been cases where market forces of urban decay are confused with new urbanism in African cities. This has led to a form of suburban mixed-use development that does not promote walkability.

Australia

Most

new developments on the edges of Australia's major cities are master

planned, often guided expressly by the principles of New Urbanism. The

relationship between housing, activity centres, the transport network

and key social infrastructure (sporting facilities, libraries, community

centres etc.) is defined at structure planning stage.

- Tullimbar Village, NSW Australia, is a new development which follows the principles of New Urbanism.

Another important factor or principle of New Urbanism that guides

Australia's major cities is how good their foot circulation seems to be

which is guided by the wayfinding systems that are implemented. Kenneth

B. Hall, Jr. and Gerald A. Porterfield said in their book, "Community by

Design," the way to gain good circulation is to take some thoughtful

consideration to things like wayfinding, sight lines, transition, visual

clues, and reference points.

Circulation design should work to create an interesting and informative

system that utilizes subtle elements as well as technical ones.

City of Port Philip, Australia, is a good example of wayfinding where

they have come up with a comprehensive pedestrian signage system,

specifically for their local areas of St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port

Melbourne.

The city's wayfinding system consists of 26 individually designed

panels that are placed on some major streets such as St Kilda and St

Kilda East, linking St Kilda Junction and Balaclava Station to the

foreshore via Fitzroy, Carlisle and Acland Streets.

City of Port Philip also created directional signage systems that makes

use of the already existing street furniture such as trash cans to help

provide for 130 directional indicators across Port Melbourne.