Decentralization is the process by which the activities of an

organization, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making,

are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative

location or group. Concepts of decentralization have been applied to group dynamics and management science in private businesses and organizations, political science, law and public administration, economics, money and technology.

History

Alexis de Tocqueville, French historian

The word "centralization" came into use in France in 1794 as the post-French Revolution French Directory leadership created a new government structure. The word "decentralization" came into usage in the 1820s. "Centralization" entered written English in the first third of the 1800s;

mentions of decentralization also first appear during those years. In the mid-1800s Tocqueville

would write that the French Revolution began with "a push towards

decentralization...[but became,] in the end, an extension of

centralization." In 1863 retired French bureaucrat Maurice Block

wrote an article called “Decentralization” for a French journal which

reviewed the dynamics of government and bureaucratic centralization and

recent French efforts at decentralization of government functions.

Ideas of liberty and decentralization were carried to their

logical conclusions during the 19th and 20th centuries by anti-state

political activists calling themselves "anarchists", "libertarians," and even decentralists. Tocqueville

was an advocate, writing: "Decentralization has, not only an

administrative value, but also a civic dimension, since it increases the

opportunities for citizens to take interest in public affairs; it makes

them get accustomed to using freedom. And from the accumulation of

these local, active, persnickety freedoms, is born the most efficient

counterweight against the claims of the central government, even if it

were supported by an impersonal, collective will." Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), influential anarchist theorist

wrote: "All my economic ideas as developed over twenty-five years can

be summed up in the words: agricultural-industrial federation. All my

political ideas boil down to a similar formula: political federation or

decentralization."

In early twentieth century America a response to the

centralization of economic wealth and political power was a decentralist

movement. It blamed large-scale industrial production for destroying

middle class shop keepers and small manufacturers and promoted increased

property ownership and a return to small scale living. The decentralist

movement attracted Southern Agrarians like Robert Penn Warren, as well as journalist Herbert Agar. New Left

and libertarian individuals who identified with social, economic, and

often political decentralism through the ensuing years included Ralph Borsodi, Wendell Berry, Paul Goodman, Carl Oglesby, Karl Hess, Donald Livingston, Kirkpatrick Sale (author of Human Scale), Murray Bookchin, Dorothy Day, Senator Mark O. Hatfield, Mildred J. Loomis, and Bill Kauffman.

Decentralization was one of ten Megatrends identified in this best seller.

Leopold Kohr, author of the 1957 book The Breakdown of Nations – known for its statement “Whenever something is wrong, something is too big” – was a major influence on E.F. Schumacher, author of the 1973 bestseller Small is Beautiful:Economics As If People Mattered. In the next few years a number of best-selling books promoted decentralization. Daniel Bell's The Coming of Post-Industrial Society

discussed the need for decentralization and a “comprehensive overhaul

of government structure to find the appropriate size and scope of

units”, as well as the need to detach functions from current state

boundaries, creating regions based on functions like water, transport,

education and economics which might have “different ‘overlays’ on the

map.” Alvin Toffler published Future Shock (1970) and The Third Wave

(1980). Discussing the books in a later interview, Toffler said that

industrial-style, centralized, top-down bureaucratic planning would be

replaced by a more open, democratic, decentralized style which he called

“anticipatory democracy.” Futurist John Naisbitt's 1982 book “Megatrends” was on The New York Times Best Seller list for more than two years and sold 14 million copies. Naisbitt's book outlines 10 “megatrends”, the fifth of which is from centralization to decentralization. In 1996 David Osborne and Ted Gaebler had a best selling book Reinventing Government proposing decentralist public administration theories which became labeled the "New Public Management".

Stephen Cummings wrote that decentralization became a "revolutionary megatrend" in the 1980s. In 1983 Diana Conyers asked if decentralization was the "latest fashion" in development administration. Cornell University's

project on Restructuring Local Government states that decentralization

refers to the "global trend" of devolving responsibilities to regional

or local governments. Robert J. Bennett's Decentralization, Intergovernmental Relations and Markets: Towards a Post-Welfare Agenda describes how after World War II

governments pursued a centralized "welfarist" policy of entitlements

which now has become a "post-welfare" policy of intergovernmental and

market-based decentralization.

In 1983, "Decentralization" was identified as one of the "Ten Key Values" of the Green Movement in the United States.

According to a 1999 United Nations Development Program report:

...large number of developing and transitional countries have embarked on some form of decentralization programs. This trend is coupled with a growing interest in the role of civil society and the private sector as partners to governments in seeking new ways of service delivery...Decentralization of governance and the strengthening of local governing capacity is in part also a function of broader societal trends. These include, for example, the growing distrust of government generally, the spectacular demise of some of the most centralized regimes in the world (especially the Soviet Union) and the emerging separatist demands that seem to routinely pop up in one or another part of the world. The movement toward local accountability and greater control over one's destiny is, however, not solely the result of the negative attitude towards central government. Rather, these developments, as we have already noted, are principally being driven by a strong desire for greater participation of citizens and private sector organizations in governance.

Overview

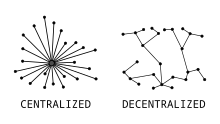

Systems approach

Graphical comparison of centralized and decentralized system.

Those studying the goals and processes of implementing decentralization often use a systems theory approach. The United Nations Development Program

report applies to the topic of decentralization "a whole systems

perspective, including levels, spheres, sectors and functions and seeing

the community level as the entry point at which holistic definitions of

development goals are most likely to emerge from the people themselves

and where it is most practical to support them. It involves seeing

multi-level frameworks and continuous, synergistic processes of

interaction and iteration of cycles as critical for achieving wholeness

in a decentralized system and for sustaining its development.”

However, has been seen as part of a systems approach. Norman Johnson of Los Alamos National Laboratory

wrote in a 1999 paper: "A decentralized system is where some decisions

by the agents are made without centralized control or processing. An

important property of agent systems is the degree of connectivity between the agents, a measure global flow of information

or influence. If each agent is connected (exchange states or influence)

to all other agents, then the system is highly connected."

University of California, Irvine's

Institute for Software Research's "PACE" project is creating an

"architectural style for trust management in decentralized

applications." It adopted Rohit Khare's

definition of decentralization: "A decentralized system is one which

requires multiple parties to make their own independent decisions" and

applies it to Peer-to-peer software creation, writing:

In such a decentralized system, there is no single centralized authority that makes decisions on behalf of all the parties. Instead each party, also called a peer, makes local autonomous decisions towards its individual goals which may possibly conflict with those of other peers. Peers directly interact with each other and share information or provide service to other peers. An open decentralized system is one in which the entry of peers is not regulated. Any peer can enter or leave the system at any time...

Goals

Decentralization

in any area is a response to the problems of centralized systems.

Decentralization in government, the topic most studied, has been seen as

a solution to problems like economic decline, government inability to

fund services and their general decline in performance of overloaded

services, the demands of minorities for a greater say in local

governance, the general weakening legitimacy of the public sector and

global and international pressure on countries with inefficient,

undemocratic, overly centralized systems. The following four goals or objectives are frequently stated in various analyses of decentralization.

Participation

In decentralization the principle of subsidiarity

is often invoked. It holds that the lowest or least centralized

authority which is capable of addressing an issue effectively should do

so. According to one definition: "Decentralization, or decentralizing

governance, refers to the restructuring or reorganization of authority

so that there is a system of co-responsibility between institutions of

governance at the central, regional and local levels according to the

principle of subsidiarity, thus increasing the overall quality and

effectiveness of the system of governance, while increasing the

authority and capacities of sub-national levels."

Decentralization is often linked to concepts of participation in

decision-making, democracy, equality and liberty from higher authority. Decentralization enhances the democratic voice.

Theorists believe that local representative authorities with actual

discretionary powers are the basis of decentralization that can lead to

local efficiency, equity and development.” Columbia University's Earth Institute

identified one of three major trends relating to decentralization as:

"increased involvement of local jurisdictions and civil society in the

management of their affairs, with new forms of participation,

consultation, and partnerships."

Decentralization has been described as a "counterpoint to

globalization" which removes decisions from the local and national stage

to the global sphere of multi-national or non-national interests.

Decentralization brings decision-making back to the sub-national levels.

Decentralization strategies must account for the interrelations of

global, regional, national, sub-national, and local levels.

Diversity

Norman L. Johnson writes that diversity plays an important role in decentralized systems like ecosystems, social groups, large organizations, political systems.

"Diversity is defined to be unique properties of entities, agents, or

individuals that are not shared by the larger group, population,

structure. Decentralized is defined as a property of a system where the

agents have some ability to operate "locally.” Both decentralization

and diversity are necessary attributes to achieve the self-organizing

properties of interest."

Advocates of political decentralization hold that greater

participation by better informed diverse interests in society will lead

to more relevant decisions than those made only by authorities on the

national level. Decentralization has been described as a response to demands for diversity.

Efficiency

In business, decentralization leads to a management by results philosophy which focuses on definite objectives to be achieved by unit results.

Decentralization of government programs is said to increase efficiency –

and effectiveness – due to reduction of congestion in communications,

quicker reaction to unanticipated problems, improved ability to deliver

services, improved information about local conditions, and more support

from beneficiaries of programs.

Firms may prefer decentralization because it ensures efficiency

by making sure that managers closest to the local information make

decisions and in a more timely fashion; that their taking responsibility

frees upper management for long term strategics rather than day-to-day

decision-making; that managers have hands on training to prepare them to

move up the management hierarchy; that managers are motivated by having

the freedom to exercise their own initiative and creativity; that

managers and divisions are encouraged to prove that they are profitable,

instead of allowing their failures to be masked by the overall

profitability of the company.

The same principles can be applied to government.

Decentralization promises to enhance efficiency through both

inter-governmental competition with market features and fiscal

discipline which assigns tax and expenditure authority to the lowest

level of government possible. It works best where members of

sub-national government have strong traditions of democracy,

accountability and professionalism.

Conflict resolution

Economic and/or political decentralization can help prevent or reduce

conflict because they reduce actual or perceived inequities between

various regions or between a region and the central government.

Dawn Brancati finds that political decentralization reduces intrastate

conflict unless politicians create political parties that mobilize

minority and even extremist groups to demand more resources and power

within national governments. However, the likelihood this will be done

depends on factors like how democratic transitions happen and features

like a regional party's proportion of legislative seats, a country's

number of regional legislatures, elector procedures, and the order in

which national and regional elections occur. Brancati holds that

decentralization can promote peace if it encourages statewide parties to

incorporate regional demands and limit the power of regional parties.

Processes

The

processes of decentralization redefines structures, procedures and

practices of governance to be closer to the citizenry and to make them

more aware of the costs and benefits; it is not merely a movement of

power from the central to the local government. According to the United

Nations Development Program, it is "more than a process, it is a way

of life and a state of mind." The report provides a chart-formatted

framework for defining the application of the concept ‘decentralization’

describing and elaborating on the "who, what, when, where, why and how"

factors in any process of decentralization.

- Initiation

The processes by which entities move from a more to a less

centralized state vary. They can be initiated from the centers of

authority ("top-down") or from individuals, localities or regions ("bottom-up"), or from a "mutually desired" combination of authorities and localities working together.

Bottom-up decentralization usually stresses political values like local

responsiveness and increased participation and tends to increase

political stability. Top-down decentralization may be motivated by the

desire to “shift deficits downwards” and find more resources to pay for

services or pay off government debt. Some hold that decentralization should not be imposed, but done in a respectful manner.

Analysis of operations

Project and program planners must assess the lowest organizational level

at which functions can be carried out efficiently and effectively.

Governments deciding to privatize functions must decide which are best

privatized. Existing types of decentralization must be studied. The

appropriate balance of centralization and decentralization should be

studied. Training for both national and local managers and officials is

necessary, as well as technical assistance in the planning, financing,

and management of decentralized functions.

Appropriate size

Gauging the appropriate size or scale of decentralized units has been studied in relation to the size of sub-units of hospitals and schools, road networks, administrative units in business and public administration, and especially town and city governmental areas and decision making bodies.

In creating planned communities

("new towns"), it is important to determine the appropriate population

and geographical size. While in earlier years small towns were

considered appropriate, by the 1960s, 60,000 inhabitants was considered

the size necessary to support a diversified job market and an adequate

shopping center and array of services and entertainment. Appropriate

size of governmental units for revenue raising also is a consideration.

Even in bioregionalism,

which seeks to reorder many functions and even the boundaries of

governments according to physical and environmental features, including watershed boundaries and soil and terrain characteristics, appropriate size must be considered. The unit may be larger than many decentralist bioregionalists prefer.

- Inadvertent or silent

Decentralization ideally happens as a careful, rational, and orderly

process, but it often takes place during times of economic and political

crisis, the fall of a regime and the resultant power struggles. Even

when it happens slowly, there is a need for experimentation, testing,

adjusting, and replicating successful experiments in other contexts.

There is no one blueprint for decentralization since it depends on the

initial state of a country and the power and views of political

interests and whether they support or oppose decentralization.

Decentralization usually is conscious process based on explicit

policies. However, it may occur as "silent decentralization" in the

absence of reforms as changes in networks, policy emphasize and resource

availability lead inevitably to a more decentralized system.

A variation on this is "inadvertent decentralization", when other policy

innovations produce an unintended decentralization of power and

resources. In both China and Russia, lower level authorities attained

greater powers than intended by central authorities.

- Asymmetry

Decentralization may be uneven and "asymmetric" given any one

country's population, political, ethnic and other forms of diversity. In

many countries, political, economic and administrative responsibilities

may be decentralized to the larger urban areas, while rural areas are

administered by the central government. Decentralization of

responsibilities to provinces may be limited only to those provinces or

states which want or are capable of handling responsibility. Some

privatization may be more appropriate to an urban than a rural area;

some types of privatization may be more appropriate for some states and

provinces but not others.

- Measurement

Measuring the amount of decentralization, especially politically, is

difficult because different studies of it use different definitions and

measurements. An OECD study quotes Chanchal Kumar Sharma as stating:

"a true assessment of the degree of decentralization in a country can

be made only if a comprehensive approach is adopted and rather than

trying to simplify the syndrome of characteristics into the single

dimension of autonomy, interrelationships of various dimensions of

decentralization are taken into account."

Determinants of decentralization

The academic literature frequently mentions the following factors as determinants of decentralization:

- "The number of major ethnic groups"

- "The degree of territorial concentration of those groups"

- "The existence of ethnic networks and communities across the border of the state"

- "The country’s dependence on natural resources and the degree to which those resources are concentrated in the region’s territory"

- "The country’s per capita income relative to that in other regions"

- "The presence of self-determination movements"

Government decentralization

Historians have described the history of governments and empires in terms of centralization and decentralization. In his 1910 The History of Nations Henry Cabot Lodge wrote that Persian king Darius I

(550-486 BC) was a master of organization and "for the first time in

history centralization becomes a political fact." He also noted that

this contrasted with the decentralization of Ancient Greece.

Since the 1980s a number of scholars have written about cycles of

centralization and decentralizations. Stephen K. Sanderson wrote that

over the last 4000 years chiefdoms and actual states have gone through

sequences of centralization and decentralization of economic, political

and social power.

Yildiz Atasoy writes this process has been going on “since the Stone

Age” through not just chiefdoms and states, but empires and today's

“hegemonic core states”.

Christopher K. Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall review other works that

detail these cycles, including works which analyze the concept of core

elites which compete with state accumulation of wealth and how their

"intra-ruling-class competition accounts for the rise and fall of

states" and of their phases of centralization and decentralization.

Rising government expenditures, poor economic performance and the rise of free market-influenced

ideas have convinced governments to decentralize their operations, to

induce competition within their services, to contract out to private

firms operating in the market, and to privatize some functions and

services entirely.

East Province, Rwanda, created in 2006 as part of a government decentralization process.

Government decentralization has both political and administrative

aspects. Its decentralization may be territorial, moving power from a

central city to other localities, and it may be functional, moving

decision-making from the top administrator of any branch of government

to lower level officials, or divesting of the function entirely through

privatization.

It has been called the "new public management"

which has been described as decentralization, management by objectives,

contracting out, competition within government and consumer

orientation.

Political

Political

decentralization signifies a reduction in the authority of national

governments over policy making by endowing its citizens or their elected

representatives with more power. It may be associated with pluralistic politics and representative government, but it also means giving citizens,

or their representatives, more influence in the formulation and

implementation of laws and policies. This process is accomplished by the

institution of reforms that either delegate a certain degree of

meaningful decision-making autonomy to sub-national tiers of government, or grant citizens the right to elect lower-level officials, like local or regional representatives. Depending on the country, this may require constitutional or statutory reforms, the development of new political parties, increased power for legislatures, the creation of local political units, and encouragement of advocacy groups.

A national government

may decide to decentralize its authority and responsibilities for a

variety of reasons. Decentralization reforms may occur for

administrative reasons, when government officials decide that certain

responsibilities and decisions would be handled best at the regional or

local level. In democracies, traditionally conservative

parties include political decentralization as a directive in their

platforms because rightist parties tend to advocate for a decrease in

the role of central government. There is also strong evidence to support

the idea that government stability increases the probability of

political decentralization, since instability brought on by gridlock between opposing parties in legislatures often impedes a government's overall ability to enact sweeping reforms.

The rise of regional ethnic parties in the national politics of parliamentary democracies is also heavily associated with the implementation of decentralization reforms.

Ethnic parties may endeavor to transfer more autonomy to their

respective regions, and as a partisan strategy, ruling parties within

the central government may cooperate by establishing regional assemblies

in order to curb the rise of ethnic parties in national elections. This phenomenon famously occurred in 1999, when the United Kingdom's Labour Party appealed to Scottish constituents by creating a semi-autonomous Scottish Parliament in order to neutralize the threat from the increasingly popular Scottish National Party at the national level.

In addition to increasing the administrative efficacy of

government and endowing citizens with more power, there are many

projected advantages to political decentralization. Individuals who take

advantage of their right to elect local and regional authorities have

been shown to have more positive attitudes toward politics, and increased opportunities for civic decision-making through participatory democracy

mechanisms like public consultations and participatory budgeting are

believed to help legitimize government institutions in the eyes of

marginalized groups.

Moreover, political decentralization is perceived as a valid means of

protecting marginalized communities at a local level from the

detrimental aspects of development and globalization driven by the state, like the degradation of local customs, codes, and beliefs. In his 2013 book, Democracy and Political Ignorance, George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin argued that political decentralization in a federal democracy confronts the widespread issue of political ignorance by allowing citizens to engage in foot voting, or moving to other jurisdictions with more favorable laws. He cites the mass migration of over one million southern-born African Americans to the North or the West to evade discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The European Union follows the principle of subsidiarity,

which holds that decision-making should be made by the most local

competent authority. The EU should decide only on enumerated issues that

a local or member state authority cannot address themselves.

Furthermore, enforcement is exclusively the domain of member states. In

Finland, the Center Party

explicitly supports decentralization. For example, government

departments have been moved from the capital Helsinki to the provinces.

The Centre supports substantial subsidies that limit potential economic

and political centralization to Helsinki.

Political decentralization does not come without its drawbacks. A

study by Fan concludes that there is an increase in corruption and

rent-seeking when there are more vertical tiers in the government, as

well as when there are higher levels of sub-national government

employment.

Other studies warn of high-level politicians that may intentionally

deprive regional and local authorities of power and resources when

conflicts arise.

In order to combat these negative forces, experts believe that

political decentralization should be supplemented with other conflict

management mechanisms like power-sharing, particularly in regions with ethnic tensions.

Administrative

Four major forms of administrative decentralization have been described.

- Deconcentration, the weakest form of decentralization, shifts responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions from officials of central governments to those in existing districts or, if necessary, new ones under direct control of the central government.

- Delegation passes down responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions to semi-autonomous organizations not wholly controlled by the central government, but ultimately accountable to it. It involves the creation of public-private enterprises or corporations, or of "authorities", special projects or service districts. All of them will have a great deal of decision-making discretion and they may be exempt from civil service requirements and may be permitted to charge users for services.

- Devolution transfers responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions to the sub-national level, such as a regional, local, or state government.

- Divestment, also called privatization, may mean merely contracting out services to private companies. Or it may mean relinquishing totally all responsibility for decision-making, finance and implementation of certain public functions. Facilities will be sold off, workers transferred or fired and private companies or non-for-profit organizations allowed to provide the services. Many of these functions originally were done by private individuals, companies, or associations and later taken over by the government, either directly, or by regulating out of business entities which competed with newly created government programs.

Fiscal

Fiscal

decentralization means decentralizing revenue raising and/or expenditure

of moneys to a lower level of government while maintaining financial

responsibility. While this process usually is called fiscal federalism

it may be relevant to unitary, federal and confederate governments.

Fiscal federalism also concerns the "vertical imbalances" where the

central government gives too much or too little money to the lower

levels. It actually can be a way of increasing central government

control of lower levels of government, if it is not linked to other

kinds of responsibilities and authority.

Fiscal decentralization can be achieved through user fees, user

participation through monetary or labor contributions, expansion of

local property or sales taxes, intergovernmental transfers of central

government tax monies to local governments through transfer payments or grants,

and authorization of municipal borrowing with national government loan

guarantees. Transfers of money may be given conditionally with

instructions or unconditionally without them.

Economic or market

Economic

decentralization can be done through privatization of public owned

functions and businesses, as described briefly above. But it also is

done through deregulation,

the abolition of restrictions on businesses competing with government

services, for example, postal services, schools, garbage collection.

Even as private companies and corporations have worked to have such

services contracted out to or privatized by them, others have worked to

have these turned over to non-profit organizations or associations.

Since the 1970s there has been deregulation of some industries,

like banking, trucking, airlines and telecommunications which resulted

generally in more competition and lower prices. According to Cato Institute,

an American libertarian think-tank, in some industries deregulation of

aspects of an industry were offset by more ambitious regulations

elsewhere that hurt consumers, the electricity industry being a prime

example.

For example, in banking, Cato Institute believes some deregulation

allowed banks to compete across state lines, increasing consumer choice,

while an actual increase in regulators and regulations forced banks to

do business the way central government regulators commanded, including

making loans to individuals incapable of repaying them, leading

eventually to the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

One example of economic decentralization, which is based on a libertarian socialist model, is decentralized economic planning.

Decentralized planning is a type of economic system in which

decision-making is distributed amongst various economic agents or

localized within production agents. An example of this method in

practice is in Kerala, India which started in 1996 as, The People's Planning in Kerala.

Some argue that government standardisation in areas from commodity market, inspection and testing procurement bidding, Building codes, professional and vocational education, trade certification, safety, etc. are necessary.

Emmanuelle Auriol and Michel Benaim write about the "comparative

benefits" of decentralization versus government regulation in the

setting of standards. They find that while there may be a need for

public regulation if public safety is at stake, private creation of

standards usually is better because "regulators or 'experts' might

misrepresent consumers' tastes and needs." As long as companies are

averse to incompatible standards, standards will be created that satisfy

needs of a modern economy.

Environmental

Central

governments themselves may own large tracts of land and control the

forest, water, mineral, wildlife and other resources they contain. They

may manage them through government operations or leasing them to private

businesses; or they may neglect them to be exploited by individuals or

groups who defy non-enforced laws against exploitation. It also may

control most private land through land-use, zoning, environmental and

other regulations.

Selling off or leasing lands can be profitable for governments willing

to relinquish control, but such programs can face public scrutiny

because of fear of a loss of heritage or of environmental damage.

Devolution of control to regional or local governments has been found to

be an effective way of dealing with these concerns. Such decentralization has happened in India and other third world nations.

Ideological decentralization

Libertarian socialist decentralization

Pierre Joseph Proudhon, anarchist theorist who advocated for a decentralist non-state system which he called "federalism"

Libertarian socialism is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic society without private property in the means of production. Libertarian socialists believe in converting present-day private productive property into common or public goods. Libertarian socialism is opposed to coercive forms of social organization. It promotes free association in place of government and opposes the social relations of capitalism, such as wage labor. The term libertarian socialism is used by some socialists to differentiate their philosophy from state socialism, and by some as a synonym for left anarchism.

Accordingly, libertarian socialists believe that "the exercise of power

in any institutionalized form – whether economic, political, religious,

or sexual – brutalizes both the wielder of power and the one over whom

it is exercised". Libertarian socialists generally place their hopes in decentralized means of direct democracy such as libertarian municipalism, citizens' assemblies, or workers' councils.

Libertarian socialists are strongly critical of coercive institutions,

which often leads them to reject the legitimacy of the state in favor of

anarchism.

Adherents propose achieving this through decentralization of political

and economic power, usually involving the socialization of most

large-scale private property and enterprise (while retaining respect for personal property).

Libertarian socialism tends to deny the legitimacy of most forms of

economically significant private property, viewing capitalist property

relations as forms of domination that are antagonistic to individual

freedom.

Political philosophies commonly described as libertarian socialist include most varieties of anarchism (especially anarchist communism, anarchist collectivism, anarcho-syndicalism, and mutualism) as well as autonomism, communalism, participism, libertarian Marxist philosophies such as council communism and Luxemburgism, and some versions of "utopian socialism" and individualist anarchism. For Murray Bookchin

"In the modern world, anarchism first appeared as a movement of the

peasantry and yeomanry against declining feudal institutions. In Germany

its foremost spokesman during the Peasant Wars was Thomas Muenzer;

in England, Gerrard Winstanley, a leading participant in the Digger

movement. The concepts held by Muenzer and Winstanley were superbly

attuned to the needs of their time – a historical period when the

majority of the population lived in the countryside and when the most

militant revolutionary forces came from an agrarian world. It would be

painfully academic to argue whether Muenzer and Winstanley could have

achieved their ideals. What is of real importance is that they spoke to

their time; their anarchist concepts followed naturally from the rural

society that furnished the bands of the peasant armies in Germany and

the New Model in England." The term "anarchist" first entered the English language in 1642, during the English Civil War, as a term of abuse, used by Royalists against their Roundhead opponents. By the time of the French Revolution some, such as the Enragés, began to use the term positively, in opposition to Jacobin centralization of power, seeing "revolutionary government" as oxymoronic. By the turn of the 19th century, the English word "anarchism" had lost its initial negative connotation.

"...industrial democracy," a system where workplaces would be "handed over to democratically organised workers' associations . . . We want these associations to be models for agriculture, industry and trade, the pioneering core of that vast federation of companies and societies woven into the common cloth of the democratic social Republic." He urged "workers to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism." This would result in "Capitalistic and proprietary exploitation, stopped everywhere, the wage system abolished, equal and just exchange guaranteed."

Workers would no longer sell their labour to a capitalist but rather work for themselves in co-operatives. Anarcho-communism calls for a confederal form in relationships of mutual aid and free association between communes as an alternative to the centralism of the nation-state. Peter Kropotkin

thus suggested that "Representative government has accomplished its

historical mission; it has given a mortal blow to court-rule; and by its

debates it has awakened public interest in public questions. But to see

in it the government of the future socialist society is to commit a

gross error. Each economic phase of life implies its own political

phase; and it is impossible to touch the very basis of the present

economic life-private property – without a corresponding change in the

very basis of the political organization. Life already shows in which

direction the change will be made. Not in increasing the powers of the

State, but in resorting to free organization and free federation in all

those branches which are now considered as attributes of the State." When the First Spanish Republic was established in 1873 after the abdication of King Amadeo, the first president, Estanislao Figueras, named Francesc Pi i Margall

Minister of the Interior. His acquaintance with Proudhon enabled Pi to

warm relations between the Republicans and the socialists in Spain. Pi i

Margall became the principal translator of Proudhon's works into

Spanish

and later briefly became president of Spain in 1873 while being the

leader of the Democratic Republican Federal Party. According to George Woodcock

"These translations were to have a profound and lasting effect on the

development of Spanish anarchism after 1870, but before that time

Proudhonian ideas, as interpreted by Pi, already provided much of the

inspiration for the federalist movement which sprang up in the early

1860's." According to the Encyclopædia Britannica "During the Spanish revolution of 1873, Pi y Margall attempted to establish a decentralized, or “cantonalist,” political system on Proudhonian lines."

To date, the best-known examples of an anarchist communist

society (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and

achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon),

are the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution and the Free Territory during the Russian Revolution. Through the efforts and influence of the Spanish Anarchists during the Spanish Revolution within the Spanish Civil War,

starting in 1936 anarchist communism existed in most of Aragon, parts

of the Levante and Andalusia, as well as in the stronghold of Anarchist Catalonia before being crushed by the combined forces of the regime that won the war, Hitler, Mussolini, Spanish Communist Party repression (backed by the USSR) as well as economic and armaments blockades from the capitalist countries and the Second Spanish Republic itself. During the Russian Revolution, anarchists such as Nestor Makhno worked to create and defend – through the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine – anarchist communism in the Free Territory of Ukraine from 1919 before being conquered by the Bolsheviks in 1921. Several libertarian socialists, notably Noam Chomsky among others, believe that anarchism shares much in common with certain variants of Marxism such as the council communism of Marxist Anton Pannekoek. In Chomsky's Notes on Anarchism, he suggests the possibility "that some form of council communism is the natural form of revolutionary socialism in an industrial

society. It reflects the belief that democracy is severely limited when

the industrial system is controlled by any form of autocratic elite,

whether of owners, managers, and technocrats, a 'vanguard' party, or a State bureaucracy."

Free market decentralization

Free market ideas popular in the 19th century, such as those of Adam Smith returned to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s. Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich von Hayek

emphasized that free markets themselves are decentralized systems where

outcomes are produced without explicit agreement or coordination by

individuals who use prices as their guide.

As Eleanor Doyle writes: "Economic decision-making in free markets is

decentralized across all the individuals dispersed in each market and is

synchronized or coordinated by the price system." The individual right

to property is part of this decentralized system. Analyzing the problems of central government control, Hayek wrote in The Road to Serfdom:

There would be no difficulty about efficient control or planning were conditions so simple that a single person or board could effectively survey all the relevant facts. It is only as the factors which have to be taken into account become so numerous that it is impossible to gain a synoptic view of them that decentralization becomes imperative.

According to Bruce M. Owen,

this does not mean that all firms themselves have to be equally

decentralized. He writes: "markets allocate resources through

arms-length transactions among decentralized actors. Much of the time,

markets work very efficiently, but there is a variety of conditions

under which firms do better. Hence, goods and services are produced and

sold by firms with various degrees of horizontal and vertical

integration." Additionally, he writes that the "economic incentive to

expand horizontally or vertically is usually, but not always, compatible

with the social interest in maximizing long-run consumer welfare." When

it does not, he writes regulation may be necessary.

It often is claimed that free markets and private property

generate centralized monopolies and other ills; the counter is that

government is the source of monopoly. Historian Gabriel Kolko in his book The Triumph of Conservatism

argued that in the first decade of the 20th century businesses were

highly decentralized and competitive, with new businesses constantly

entering existing industries. There was no trend towards concentration

and monopolization. While there were a wave of mergers of companies

trying to corner markets, they found there was too much competition to

do so. This also was true in banking and finance, which saw

decentralization as leading to instability as state and local banks

competed with the big New York City firms. The largest firms turned to the power of the state and working with leaders like United States Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft and Woodrow Wilson passed as "progressive reforms" centralizing laws like The Federal Reserve Act

of 1913 that gave control of the monetary system to the wealthiest

bankers; the formation of monopoly "public utilities" that made

competition with those monopolies illegal; federal inspection of meat

packers biased against small companies; extending Interstate Commerce Commission to regulating telephone companies and keeping rates high to benefit AT&T; and using the Sherman Anti-trust Act against companies which might combine to threaten larger or monopoly companies.

When government licensing, franchises, and other legal restrictions

create monopoly and protect companies from open competition,

deregulation is the solution.

Author and activist Jane Jacobs's influential 1961 book The Death and Life of American Cities

criticized large-scale redevelopment projects which were part of

government-planned decentralization of population and businesses to

suburbs. She believed it destroyed cities' economies and impoverished

remaining residents. Her 1980 book The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty supported secession of Quebec from Canada. Her 1984 book Cities and the Wealth of Nations

proposed a solution to the various ills plaguing cities whose economies

were being ruined by centralized national governments: decentralization

through the "multiplication of sovereignty", i.e., acceptance of the

right of cities to secede from the larger nation states that were

squelching their ability to produce wealth.

Technological decentralization

The Living Machine installation in the lobby of the Port of Portland

headquarters, which was completed and ready for occupation May 2010.

The decentralized wastewater reuse system contributed to the

headquarter’s certification as a LEED Platinum building by the U.S. Green Building Council.

Technological decentralization can be defined as a shift from concentrated to distributed modes of production and consumption of goods and services.

Generally, such shifts are accompanied by transformations in technology

and different technologies are applied for either system. Technology

includes tools, materials, skills, techniques and processes by which

goals are accomplished in the public and private spheres. Concepts of

decentralization of technology are used throughout all types of technology, including especially information technology and appropriate technology.

Technologies often mentioned as best implemented in a

decentralized manner, include: water purification, delivery and waste

water disposal, agricultural technology and energy technology.

Advancing technology may allow decentralized, privatized and free

market solutions for what have been public services, such utilities

producing and/or delivering power, water, mail, telecommunications and

services like consumer product safety, money and banking, medical

licensing and detection and metering technologies for highways, parking,

and auto emissions.

However, in terms of technology, a clear distinction between fully

centralized or decentralized technical solutions is often not possible

and therefore finding an optimal degree of centralization difficult from

an infrastructure planning perspective.

Information technology

Information

technology encompasses computers and computer networks, as well as

information distribution technologies such as television and telephones.

The whole computer industry of computer hardware, software, electronics, internet, telecommunications equipment, e-commerce and computer services are included.

Executives and managers face a constant tension between

centralizing and decentralizing information technology for their

organizations. They must find the right balance of centralizing which

lowers costs and allows more control by upper management, and

decentralizing which allows sub-units and users more control. This will

depend on analysis of the specific situation. Decentralization is

particularly applicable to business or management units which have a

high level of independence, complicated products and customers, and

technology less relevant to other units.

Information technology applied to government communications with citizens, often called e-Government, is supposed to support decentralization and democratization. Various forms have been instituted in most nations worldwide.

The internet

is an example of an extremely decentralized network, having no owners

at all (although some have argued that this is less the case in recent

years).

"No one is in charge of internet, and everyone is." As long as they

follow a certain minimal number of rules, anyone can be a service

provider or a user. Voluntary boards establish protocols, but cannot

stop anyone from developing new ones. Other examples of open source or decentralized movements are Wikis which allow users to add, modify, or delete content via the internet. Wikipedia has been described as decentralized. Smartphones have greatly increased the role of decentralized social network services in daily lives worldwide.

Decentralization continues throughout the industry, for example

as the decentralized architecture of wireless routers installed in homes

and offices supplement and even replace phone companies relatively

centralized long-range cell towers.

Inspired by system and cybernetics theorists like Norbert Wiener, Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller, in the 1960s Stewart Brand started the Whole Earth Catalog and later computer networking efforts to bring Silicon Valley computer technologists and entrepreneurs together with countercultural ideas. This resulted in ideas like personal computing, virtual communities

and the vision of an "electronic frontier" which would be a more

decentralized, egalitarian and free-market libertarian society. Related

ideas coming out of Silicon Valley included the free software and

creative commons movements which produced visions of a "networked information economy".

Because human interactions in cyberspace

transcend physical geography, there is a necessity for new theories in

legal and other rule-making systems to deal with decentralized

decision-making processes in such systems. For example, what rules

should apply to conduct on the global digital network and who should set

them? The laws of which nations govern issues of internet transactions

(like seller disclosure requirements or definitions of "fraud"),

copyright and trademark?

Centralization and redecentralization of the Internet

The New Yorker

reports that although the Internet was originally decentralized, in

recent years it has become less so: "a staggering percentage of

communications flow through a small set of corporations – and thus,

under the profound influence of those companies and other institutions

[...] One solution, espoused by some programmers, is to make the

Internet more like it used to be – less centralized and more

distributed."

Examples of projects that attempt to contribute to the redecentralization of the Internet include ArkOS, Diaspora, FreedomBox, Namecoin, SAFE Network, twtxt and ZeroNet as well as advocacy group Redecentralize.org, which provides support for projects that aim to make the Web less centralized.

In an interview with BBC Radio 5 Live one of the co-founders of Redecentralize.org explained that:

As we've gone on there's been more and more internet traffic focused through particular nodes such as Google or Facebook. [...] Centralized services that hold all the user data and host it themselves have become increasingly popular because that business model has worked. As the Internet has become more mass market, people are not necessarily willing or knowledgeable to host it themselves, so where that hosting is outsourced it's become the default, which allows a centralization of power and a centralization of data that I think is worrying.

Appropriate technology

"Appropriate technology", originally described as "intermediate technology" by economist E. F. Schumacher in Small is Beautiful, is generally recognized as encompassing technologies that are small-scale, decentralized, labor-intensive, energy-efficient, environmentally sound, and locally controlled. It is most commonly discussed as an alternative to transfers of capital-intensive technology from industrialized nations to developing countries. Even developed countries developed appropriate technologies, as did the United States in 1977 when it created the National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT), though funding later dropped off.

A related concept is "design for the other 90 percent" – low-cost

solutions for the great majority of the world's low income people.

Blockchain technology

Like the internet, blockchain

technology is designed to be decentralized, with “layers,” where each

layer is defined by an interoperable open protocol on top of which

companies, as well as individuals, can build products and services. Bitcoin is the most notorious application of the blockchain. Blockchain technology has been adopted in various areas, namely cryptocurrencies and military information.

R4 has been adopted by Barclays Investment, while bitcoin

drives adoption of its underlying blockchain, and its strong technical

community and robust code review process make it the most secure and

reliable of the various blockchains.

Decentralized applications and decentralized blockchain-based organizations could be more difficult for governments to control and regulate.

Critiques

Factors

hindering decentralization include weak local administrative or

technical capacity, which may result in inefficient or ineffective

services; inadequate financial resources available to perform new local

responsibilities, especially in the start-up phase when they are most

needed; or inequitable distribution of resources. Decentralization can

make national policy coordination too complex; it may allow local elites

to capture functions; local cooperation may be undermined by any

distrust between private and public sectors; decentralization may result

in higher enforcement costs and conflict for resources if there is no

higher level of authority.

Additionally, decentralization may not be as efficient for

standardized, routine, network-based services, as opposed to those that

need more complicated inputs. If there is a loss of economies of scale

in procurement of labor or resources, the expense of decentralization

can rise, even as central governments lose control over financial

resources.

Other challenges, and even dangers, include the possibility that

corrupt local elites can capture regional or local power centers, while

constituents lose representation; patronage politics will become rampant

and civil servants feel compromised; further necessary decentralization

can be stymied; incomplete information and hidden decision-making can

occur up and down the hierarchies; centralized power centers can find

reasons to frustrate decentralization and bring power back to

themselves.

It has been noted that while decentralization may increase

"productive efficiency" it may undermine "allocative efficiency" by

making redistribution of wealth more difficult. Decentralization will

cause greater disparities between rich and poor regions, especially

during times of crisis when the national government may not be able to

help regions needing it.

Averting the dangers of decentralization: eight classic conditions

The

literature identifies eight essential preconditions that must be

ensured while implementing decentralization in order to avert the

so-called "dangers of decentralization". These are:

- Social Preparedness and Mechanisms to Prevent Elite Capture

- Strong Administrative and Technical Capacity at the Higher Levels

- Strong Political Commitment at the Higher Levels

- Sustained Initiatives for Capacity-Building at the Local Level

- Strong Legal Framework for Transparency and Accountability

- Transformation of Local Government Organizations into High Performing Organizations

- Appropriate Reasons to Decentralize: Intentions Matter

- Effective Judicial System, Citizens' Oversight and Anticorruption Bodies to prevent Decentralization of Corruption