| Neo-Confucianism | |

| Traditional Chinese | 宋明理學 |

|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 宋明理学 |

| Literal meaning | "Song-Ming [dynasty] rational idealism" |

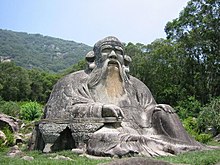

Neo-Confucianism (Chinese: 宋明理學; pinyin: Sòng-Míng lǐxué, often shortened to lixue 理學) is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, and originated with Han Yu and Li Ao (772–841) in the Tang Dynasty, and became prominent during the Song and Ming dynasties.

Neo-Confucianism could have been an attempt to create a more rationalist and secular form of Confucianism by rejecting superstitious and mystical elements of Taoism and Buddhism that had influenced Confucianism during and after the Han Dynasty.

Although the neo-Confucianists were critical of Taoism and Buddhism,

the two did have an influence on the philosophy, and the

neo-Confucianists borrowed terms and concepts. However, unlike the

Buddhists and Taoists, who saw metaphysics

as a catalyst for spiritual development, religious enlightenment, and

immortality, the neo-Confucanists used metaphysics as a guide for

developing a rationalist ethical philosophy.

Origins

Bronze statue of Zhou Dunyi(周敦颐) in White Deer Grotto Academy(白鹿洞書院)

Neo-Confucianism has its origins in the Tang Dynasty; the Confucianist scholars Han Yu and Li Ao are seen as forebears of the neo-Confucianists of the Song Dynasty. The Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi

(1017–1073) is seen as the first true "pioneer" of neo-Confucianism,

using Daoist metaphysics as a framework for his ethical philosophy.

Neo-Confucianism developed both as a renaissance of traditional

Confucian ideas, and as a reaction to the ideas of Buddhism and

religious Daoism. Although the neo-Confucianists denounced Buddhist

metaphysics, neo-Confucianism did borrow Daoist and Buddhist terminology

and concepts.

One of the most important exponents of neo-Confucianism was Zhu Xi

(1130–1200). He was a rather prolific writer, maintaining and defending

his Confucian beliefs of social harmony and proper personal conduct.

One of his most remembered was the book Family Rituals, where he

provided detailed advice on how to conduct weddings, funerals, family

ceremonies, and the veneration of ancestors. Buddhist thought soon

attracted him, and he began to argue in Confucian style for the Buddhist

observance of high moral standards. He also believed that it was

important to practical affairs that one should engage in both academic

and philosophical pursuits, although his writings are concentrated more

on issues of theoretical (as opposed to practical) significance. It is

reputed that he wrote many essays attempting to explain how his ideas

were not Buddhist or Taoist, and included some heated denunciations of

Buddhism and Taoism.

After the Xining era (1070), Wang Yangming

(1472–1529) is commonly regarded as the most important neo-Confucian

thinker. Wang's interpretation of Confucianism denied the rationalist

dualism of Zhu's orthodox philosophy.

There were many competing views within the neo-Confucian

community, but overall, a system emerged that resembled both Buddhist

and Taoist (Daoist) thought of the time and some of the ideas expressed in the I Ching (Book of Changes) as well as other yin yang theories associated with the Taiji symbol (Taijitu). A well known neo-Confucian motif is paintings of Confucius, Buddha, and Lao Tzu all drinking out of the same vinegar jar, paintings associated with the slogan "The three teachings are one!"

While neo-Confucianism incorporated Buddhist and Taoist ideas,

many neo-Confucianists strongly opposed Buddhism and Taoism. Indeed,

they rejected the Buddhist and Taoist religions. One of Han Yu's most famous essays decries the worship of Buddhist relics. Nonetheless, neo-Confucian writings adapted Buddhist thoughts and beliefs to the Confucian interest. In China

neo-Confucianism was an officially recognized creed from its

development during the Song dynasty until the early twentieth century,

and lands in the sphere of Song China (Vietnam and Japan) were all deeply influenced by neo-Confucianism for more than half a millennium.

Philosophy

Neo-Confucianism

is a social and ethical philosophy using metaphysical ideas, some

borrowed from Taoism, as its framework. The philosophy can be

characterized as humanistic and rationalistic, with the belief that the

universe could be understood through human reason, and that it was up to

humanity to create a harmonious relationship between the universe and

the individual.

The rationalism of neo-Confucianism is in contrast to the mysticism of the previously dominant Chan Buddhism.

Unlike the Buddhists, the neo-Confucians believed that reality existed,

and could be understood by humankind, even if the interpretations of

reality were slightly different depending on the school of

neo-Confucianism.

But the spirit of Neo-Confucian rationalism is diametrically opposed to that of Buddhist mysticism. Whereas Buddhism insisted on the unreality of things, Neo-Confucianism stressed their reality. Buddhism and Taoism asserted that existence came out of, and returned to, non-existence; Neo-Confucianism regarded reality as a gradual realization of the Great Ultimate... Buddhists, and to some degree, Taoists as well, relied on meditation and insight to achieve supreme reason; the Neo-Confucianists chose to follow Reason.

The importance of li in Neo-Confucianism gave the movement its Chinese name, literally "The study of Li."

Schools

Neo-Confucianism was a heterogeneous philosophical tradition, and is generally categorized into two different schools.

Two-school model vs. three-school model

In medieval China, the mainstream of neo-Confucian thought, dubbed the "Tao school", had long categorized a thinker named Lu Jiuyuan among the unorthodox, non-Confucian writers. However, in the 15th century, the esteemed philosopher Wang Yangming took sides with Lu and critiqued some of the foundations of the Tao school, albeit not rejecting the school entirely.

Objections arose to Yangming's philosophy within his lifetime, and

shortly after his death, Chen Jian (1497–1567) grouped Wang together

with Lu as unorthodox writers, dividing neo-Confucianism into two

schools.

As a result, neo-Confucianism today is generally categorized into two

different schools of thought. The school that remained dominant

throughout the medieval and early modern periods is called the Cheng-Zhu school for the esteem it places in Cheng Yi, Cheng Hao, and Zhu Xi. The less dominant, opposing school was the Lu–Wang school, based on its esteem for Lu Jiuyuan and Wang Yangming.

In contrast to this two-branch model, the New Confucian Mou Zongsan argues that there existed a third branch of learning, the Hu-Liu school, based on the teachings of Hu Hong (Hu Wufeng, 1106–61) and Liu Zongzhou

(Liu Jishan, 1578–1645). The significance of this third branch,

according to Mou, was that they represented the direct lineage of the

pioneers of neo-Confucianism, Zhou Dunyi, Zhang Zai and Cheng Hao.

Moreover, this third Hu-Liu school and the second Lu–Wang school, combined, form the true mainstream of neo-Confucianism instead of the Cheng-Zhu school. The mainstream represented a return to the teachings of Confucius, Mengzi, the Doctrine of the Mean and the Commentaries of the Book of Changes. The Cheng-Zhu school was therefore only a minority branch based on the Great Learning and mistakenly emphasized intellectual studies over the study of sagehood.

Cheng-Zhu school

Zhu Xi's formulation of the neo-Confucian world view is as follows. He believed that the Tao (Chinese: 道; pinyin: dào; literally: 'way') of Tian (Chinese: 天; pinyin: tiān; literally: 'heaven') is expressed in principle or li (Chinese: 理; pinyin: lǐ), but that it is sheathed in matter or qi (Chinese: 氣; pinyin: qì). In this, his system is based on Buddhist systems of the time that divided things into principle (again, li), and function (Chinese: 事; pinyin: shì). In the neo-Confucian formulation, li in itself is pure and almost-perfect, but with the addition of qi, base emotions and conflicts arise. Human nature is originally good, the neo-Confucians argued (following Mencius), but not pure unless action is taken to purify it. The imperative is then to purify one's li.

However, in contrast to Buddhists and Taoists, neo-Confucians did not

believe in an external world unconnected with the world of matter. In

addition, neo-Confucians in general rejected the idea of reincarnation

and the associated idea of karma.

Different neo-Confucians had differing ideas for how to do so. Zhu Xi believed in gewu (Chinese: 格物; pinyin: géwù), the Investigation of Things, essentially an academic form of observational science, based on the idea that li lies within the world.

Lu–Wang school

Wang Yangming (Wang Shouren), probably the second most influential neo-Confucian, came to another conclusion: namely, that if li is in all things, and li is in one's heart-mind, there is no better place to seek than within oneself. His preferred method of doing so was jingzuo (Chinese: 靜坐; pinyin: jìngzuò; literally: 'quiet sitting'), a practice that strongly resembles zazen or Chan (Zen) meditation. Wang Yangming developed the idea of innate knowing, arguing that every person knows from birth the difference between good and evil. Such knowledge is intuitive and not rational. These revolutionizing ideas of Wang Yangming would later inspire prominent Japanese thinkers like Motoori Norinaga, who argued that because of the Shinto

deities, Japanese people alone had the intuitive ability to distinguish

good and evil without complex rationalization. Wang Yangming's school

of thought (Ōyōmei-gaku in Japanese) also provided, in part, an

ideological basis for some samurai who sought to pursue action based on

intuition rather than scholasticism. As such, it also provided an

intellectual foundation for the radical political actions of low ranking

samurai in the decades prior to the Meiji Ishin (1868), in which the

Tokugawa authority (1600–1868) was overthrown.

Neo-Confucianism in Korea

In Joseon Korea, neo-Confucianism was established as the state ideology. The Yuan occupation of the Korean peninsula introduced Zhu Xi's school of neo-Confucianism to Korea. Neo-Confucianism was introduced to Korea by An Hyang during Goryeo dynasty.

At the time that An Hyang introduced neo-Confucianism, the Goryeo

dynasty was in the last century of its existence and influenced by the

Mongol Yuan dynasty.

Many Korean scholars visited China during the Yuan dynasty and An Hyang was among them. In 1286, he happened to read a book of Zhu Xi in Yanjing.

He was so moved by this book that he transcribed this book in its

entirety and came back to Korea with his transcribed copy. It greatly

inspired Korean intellectuals at the time and many, predominantly from

the middle class and disillusioned with the excesses of organized

religion (in the form of Buddhism) and the old nobility, embraced

neo-Confucianism. The newly rising neo-Confucian intellectuals were

leading groups aimed at the overthrow of the old (and increasingly

foreign-influenced) Goryeo dynasty.

Portrait of Jo Gwang-jo

After the fall of the Goryeo dynasty and the establishment of the Joseon Dynasty by Yi Song-gye

in 1392 AD, neo-Confucianism was installed as the new dynasty's state

ideology. Buddhism, and organized religion in general was considered

poisonous to the neo-Confucian order. Buddhism was accordingly

restricted and occasionally persecuted by the new dynasty. As

neo-Confucianism encouraged education, there were a number of

neo-Confucian schools (서원 seowon and 향교 hyanggyo) founded throughout the country. Such schools produced many neo-Confucian scholars, including individuals such as Jo Gwang-jo (조광조, 趙光祖; 1482–1520), Yi Hwang (이황, 李滉; pen name Toegye 퇴계, 退溪; 1501–1570)

and Yi I (이이, 李珥; 1536–1584).

In the early 16th century, Jo Gwang-jo attempted to transform

Joseon into the ideal neo-Confucian society with a series of radical

reforms until he was executed in 1520. Despite the failure of his

attempted reforms, neo-Confucianism soon assumed an even greater role in

the Joseon Dynasty. Soon Korean neo-Confucian scholars, no longer

content to only read and remember the Chinese original precepts, began

to develop new neo-Confucian theories. Yi Hwang and Yi I were the most prominent of these new theorists.

Yi Hwang's most prominent disciples were Kim Seong-il (金誠一, 1538–1593), Yu Seong-ryong (柳成龍 1542–1607)and Jeong Gu (한강 정구, 寒岡 鄭逑, 1543—1620), known as the "three heroes".

These were followed by a second generation of scholars which included Jang Hyungwang (張顯光, 1554—1637)

and Jang Heung-Hyo (敬堂 張興孝, 1564—1633), and by a third generation (including Heo Mok, Yun Hyu, Yun Seon-do, Song Si-yeol) which brought the school into the 18th century.

But neo-Confucianism in the Joseon Dynasty became so dogmatic in a

relatively rapid time that it prevented much needed socio-economic

development and change, and led to internal divisions and criticism of

many new theories, regardless of their popular appeal. For instance, Wang Yangming's theories, which were popular in the Chinese Ming Dynasty,

were regarded as heresy and severely condemned by Korean

neo-Confucianists. Furthermore, any annotations on Confucian canon which

are different from Zhu Xi were excluded. During the Joseon Dynasty, the

newly emerging ruling class, called Sarim(사림,

士林), also became divided into political factions according to their

diversity of neo-Confucian views on politics. There were two large

factions and many subfactions.

During the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), many Korean neo-Confucian books and scholars were taken to Japan. They influenced Japanese scholars such as Fujiwara Seika and affected the development of Japanese neo-Confucianism.

Bureaucratic examinations

Neo-Confucianism became the interpretation of Confucianism whose mastery was necessary to pass the bureaucratic examinations by the Ming,

and continued in this way through the Qing dynasty until the end of the

Imperial examination system in 1905. However, many scholars such as Benjamin Elman have questioned the degree to which their role as the orthodox interpretation in state examinations reflects the degree to which both the bureaucrats and Chinese gentry actually believed those interpretations, and point out that there were very active schools such as Han learning which offered competing interpretations of Confucianism.

The competing school of Confucianism was called the Evidential School or Han Learning

and argued that neo-Confucianism had caused the teachings of

Confucianism to be hopelessly contaminated with Buddhist thinking. This

school also criticized neo-Confucianism for being overly concerned with

empty philosophical speculation that was unconnected with reality.

Confucian canon

The Confucian canon as it exists today was essentially compiled by Zhu Xi. Zhu codified the canon of Four Books (the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Analects of Confucius, and the Mencius)

which in the subsequent Ming and Qing Dynasties were made the core of

the official curriculum for the civil service examinations.

New Confucianism

In the 1920s, New Confucianism,

also known as modern neo-Confucianism, started developing and absorbed

the Western learning to seek a way to modernize Chinese culture based on

the traditional Confucianism. It centers on four topics: The modern

transformation of Chinese culture; Humanistic spirit of Chinese culture;

Religious connotation in Chinese culture; Intuitive way of thinking, to

go beyond the logic and to wipe out the concept of exclusion analysis.

Adhering to the traditional Confucianism and the neo-confucianism, the

modern neo-Confucianism contributes the nation's emerging from the

predicament faced by the ancient Chinese traditional culture in the

process of modernization; Furthermore, it also promotes the world

culture of industrial civilization rather than the traditional personal

senses.

Prominent neo-Confucian scholars

China

- Cheng Yi and Cheng Hao

- Lu Xiangshan also known as Lu Jiuyuan (1139–1193)

- Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072)

- Shao Yong (1011–1077)

- Su Shi, also known as Su Dongpo (1037–1101)

- Wang Yangming also known as Wang Shouren

- Wu Cheng (1249-1333)

- Ye Shi (1150–1223)

- Zhang Shi (1133–1180)

- Zhang Zai

- Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073)

- Zhu Xi (1130–1200)

- Cheng Duanli (1271–1345)

Korea

- An Hyang (1243–1306)

- U Tak (1263-1342)

- Yi Saek (1328–1396)

- Jeong Mong-ju (1337–1392)

- Jeong Dojeon (1342–1398)

- Gil Jae (1353–1419)

- Ha Ryun

- Gwon Geun

- Jeong Inji (1396–1478)

- Kim Suk-ja

- Kim Jong-jik (1431–1492)

- Nam Hyo-on

- Kim Goil-pil

- Jo Gwang-jo (1482–1519)

- Seo Gyeongdeok

- Yi Eon-jeok

- Yi Hwang (Pen name Toegye) (1501–1570)

- Jo Sik (1501–1572)

- Ryu Seongryong

- Yi Hang

- Kim Inhu

- Ki Daeseung (1527–1572)

- Song Ik-pil (1534–1599)

- Seong Hon (1535–1598)

- Yi I (Pen name Yulgok) (1536–1584)

- Kim Jangsaeng (1548–1631)

- Song Si-yeol (1607–1689)

- Yi Gan (1677–1727)

- Yi Ik (1681–1763)

- Han Wonjin (1682–1751)

- Hong Daeyong (1731–1783)

- Park Jiwon (1737–1805)

- Park Jega (1750–1815)

- Jeong Yak-yong (1762–1836)

Japan

- Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619)

- Hayashi Razan (1583–1657)

- Nakae Tōju (1608–1648)

- Yamazaki Ansai (1619–1682)

- Kumazawa Banzan (1619–1691)

- Yamaga Sokō (1622–1685)

- Itō Jinsai (1627–1705)

- Kaibara Ekken (also known as Ekiken) (1630–1714)

- Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725)

- Ogyū Sorai (1666–1728)

- Nakai Chikuzan (1730–1804)

- Ōshio Heihachirō (1793–1837)

Vietnam

- Chu Văn An (1292–1370)

- Lê Quý Đôn (1726–1784)

- Nguyễn Khuyến (1835–1909)

- Phan Đình Phùng (1847–1896)

- Tự Đức (1829–1883)