In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since actions intended to lower inflation may exacerbate unemployment.

The term, a portmanteau of stagnation and inflation, is generally attributed to Iain Macleod, a British Conservative Party politician who became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1970. Macleod used the word in a 1965 speech to Parliament during a period of simultaneously high inflation and unemployment in the United Kingdom. Warning the House of Commons of the gravity of the situation, he said:

John Maynard Keynes did not use the term, but some of his work refers to the conditions that most would recognise as stagflation. In the version of Keynesian macroeconomic theory that was dominant between the end of World War II and the late 1970s, inflation and recession were regarded as mutually exclusive, the relationship between the two being described by the Phillips curve. Stagflation is very costly and difficult to eradicate once it starts, both in social terms and in budget deficits.

The term, a portmanteau of stagnation and inflation, is generally attributed to Iain Macleod, a British Conservative Party politician who became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1970. Macleod used the word in a 1965 speech to Parliament during a period of simultaneously high inflation and unemployment in the United Kingdom. Warning the House of Commons of the gravity of the situation, he said:

We now have the worst of both worlds—not just inflation on the one side or stagnation on the other, but both of them together. We have a sort of "stagflation" situation. And history, in modern terms, is indeed being made.Macleod used the term again on 7 July 1970, and the media began also to use it, for example in The Economist on 15 August 1970, and Newsweek on 19 March 1973.

John Maynard Keynes did not use the term, but some of his work refers to the conditions that most would recognise as stagflation. In the version of Keynesian macroeconomic theory that was dominant between the end of World War II and the late 1970s, inflation and recession were regarded as mutually exclusive, the relationship between the two being described by the Phillips curve. Stagflation is very costly and difficult to eradicate once it starts, both in social terms and in budget deficits.

The Great Inflation

The term stagflation, a portmanteau of stagnation and inflation,

was first coined during a period of inflation and unemployment in the

United Kingdom. The United Kingdom experienced an outbreak of inflation

in the 1960s and 1970s. Inflation rose in the 1960s and 1970s, UK policy

makers failed to recognize the primary role of monetary policy in

controlling inflation. Instead, they attempted to use non-monetary

policies and devices to respond to the economic crisis. Policy makers

also made "inaccurate estimates of the degree of excess demand in the

economy, [which] contributed significantly to the outbreak of inflation

in the United Kingdom in the 1960s and 1970s.

Stagflation was not limited to the United Kingdom, however.

Economists have shown that stagflation was prevalent among seven major

market economies from 1973 to 1982.

After inflation rates began to fall in 1982, economists' focus shifted

from the causes of stagflation to the "determinants of productivity

growth and the effects of real wages on the demand for labor".

Causes

Economists offer two principal explanations for why stagflation occurs. First, stagflation can result when the economy faces a supply shock, such as a rapid increase in the price of oil. An unfavorable situation like that tends to raise prices at the same time as it slows economic growth by making production more costly and less profitable.

Second, the government can cause stagflation if it creates

policies that harm industry while growing the money supply too quickly.

These two things would probably have to occur simultaneously because

policies that slow economic growth do not usually cause inflation, and

policies that cause inflation do not usually slow economic growth.

Both explanations are offered in analyses of the 1970s stagflation in the West.

It began with a huge rise in oil prices, but then continued as central

banks used excessively stimulative monetary policy to counteract the

resulting recession, causing a price/wage spiral.

Postwar Keynesian and monetarist views

Early Keynesianism and monetarism

Up to the 1960s, many Keynesian

economists ignored the possibility of stagflation, because historical

experience suggested that high unemployment was typically associated

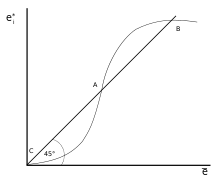

with low inflation, and vice versa (this relationship is called the Phillips curve).

The idea was that high demand for goods drives up prices, and also

encourages firms to hire more; and likewise high employment raises

demand. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, when stagflation occurred, it

became obvious that the relationship between inflation and employment

levels was not necessarily stable: that is, the Phillips relationship

could shift. Macroeconomists became more skeptical of Keynesian

theories, and Keynesians themselves reconsidered their ideas in search

of an explanation for stagflation.

The explanation for the shift of the Phillips curve was initially provided by the monetarist economist Milton Friedman, and also by Edmund Phelps.

Both argued that when workers and firms begin to expect more inflation,

the Phillips curve shifts up (meaning that more inflation occurs at any

given level of unemployment). In particular, they suggested that if

inflation lasted for several years, workers and firms would start to

take it into account during wage negotiations, causing workers' wages

and firms' costs to rise more quickly, thus further increasing

inflation. While this idea was a severe criticism of early Keynesian

theories, it was gradually accepted by most Keynesians, and has been

incorporated into New Keynesian economic models.

Neo-Keynesianism

Neo-Keynesian theory distinguished two distinct kinds of inflation: demand-pull

(caused by shifts of the aggregate demand curve) and cost-push (caused

by shifts of the aggregate supply curve). Stagflation, in this view, is

caused by cost-push inflation.

Cost-push inflation occurs when some force or condition increases the

costs of production. This could be caused by government policies (such

as taxes) or from purely external factors such as a shortage of natural

resources or an act of war.

Contemporary Keynesian analyses argue that stagflation can be understood by distinguishing factors that affect aggregate demand from those that affect aggregate supply.

While monetary and fiscal policy can be used to stabilise the economy

in the face of aggregate demand fluctuations, they are not very useful

in confronting aggregate supply fluctuations. In particular, an adverse

shock to aggregate supply, such as an increase in oil prices, can give

rise to stagflation.

Supply theory

Fundamentals

Supply

theories are based on the neo-Keynesian cost-push model and attribute

stagflation to significant disruptions to the supply side of the

supply-demand market equation, such as when there is a sudden real or

relative scarcity of key commodities, natural resources, or natural capital needed to produce goods and services.

Other factors may also cause supply problems, for example, social and

political conditions such as policy changes, acts of war, extremely

restrictive government control of production. In this view, stagflation is thought to occur when there is an adverse supply shock (for example, a sudden increase in the price of oil

or a new tax) that causes a subsequent jump in the "cost" of goods and

services (often at the wholesale level). In technical terms, this

results in contraction or negative shift in an economy's aggregate supply curve.

In the resource scarcity scenario (Zinam 1982), stagflation

results when economic growth is inhibited by a restricted supply of raw

materials.

That is, when the actual or relative supply of basic materials (fossil

fuels (energy), minerals, agricultural land in production, timber,

etc.) decreases and/or cannot be increased fast enough in response to

rising or continuing demand. The resource shortage may be a real

physical shortage, or a relative scarcity due to factors such as taxes

or bad monetary policy influencing the "cost" or availability of raw

materials. This is consistent with the cost-push inflation factors in

neo-Keynesian theory (above). The way this plays out is that after

supply shock occurs, the economy first tries to maintain momentum. That

is, consumers and businesses begin paying higher prices to maintain

their level of demand. The central bank may exacerbate this by

increasing the money supply, by lowering interest rates for example, in

an effort to combat a recession. The increased money supply props up the

demand for goods and services, though demand would normally drop during

a recession.

In the Keynesian model, higher prices prompt increases in the

supply of goods and services. However, during a supply shock (i.e.,

scarcity, "bottleneck" in resources, etc.), supplies do not respond as

they normally would to these price pressures. So, inflation jumps and

output drops, producing stagflation.

Explaining the 1970s stagflation

Following Richard Nixon's imposition of wage and price controls

on 15 August 1971, an initial wave of cost-push shocks in commodities

were blamed for causing spiraling prices. The second major shock was the

1973 oil crisis, when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) constrained the worldwide supply of oil. Both events, combined with the overall energy shortage

that characterized the 1970s, resulted in actual or relative scarcity

of raw materials. The price controls resulted in shortages at the point

of purchase, causing, for example, queues of consumers at fuelling

stations and increased production costs for industry.

Recent views

Through the mid-1970s, it was alleged that none of the major macroeconomic models (Keynesian, New Classical, and monetarist) were able to explain stagflation.

Later, an explanation was provided based on the effects of adverse supply shocks on both inflation and output. According to Blanchard (2009), these adverse events were one of two components of stagflation; the other was "ideas"—which Robert Lucas, Thomas Sargent, and Robert Barro were cited as expressing as "wildly incorrect" and "fundamentally flawed" predictions (of Keynesian economics) which, they said, left stagflation to be explained by "contemporary students of the business cycle". In this discussion, Blanchard hypothesizes that the recent oil price increases could trigger another period of stagflation, although this has not yet happened (pg. 152).

Neoclassical views

A purely neoclassical view of the macroeconomy rejects the idea that monetary policy can have real effects. Neoclassical macroeconomists argue that real economic quantities, like real output, employment, and unemployment, are determined by real factors only. Nominal

factors like changes in the money supply only affect nominal variables

like inflation. The neoclassical idea that nominal factors cannot have

real effects is often called monetary neutrality or also the classical dichotomy.

Since the neoclassical viewpoint says that real phenomena like

unemployment are essentially unrelated to nominal phenomena like

inflation, a neoclassical economist would offer two separate

explanations for 'stagnation' and 'inflation'. Neoclassical explanations

of stagnation (low growth and high unemployment) include inefficient

government regulations or high benefits for the unemployed that give

people less incentive to look for jobs. Another neoclassical

explanation of stagnation is given by real business cycle theory, in which any decrease in labour productivity makes it efficient to work less. The main neoclassical explanation of inflation is very simple: it happens when the monetary authorities increase the money supply too much.

In the neoclassical viewpoint, the real factors that determine output and unemployment affect the aggregate supply curve only. The nominal factors that determine inflation affect the aggregate demand curve only.

When some adverse changes in real factors are shifting the aggregate

supply curve left at the same time that unwise monetary policies are

shifting the aggregate demand curve right, the result is stagflation.

Thus the main explanation for stagflation under a classical view

of the economy is simply policy errors that affect both inflation and

the labour market. Ironically, a very clear argument in favour of the

classical explanation of stagflation was provided by Keynes himself. In

1919, John Maynard Keynes described the inflation and economic stagnation gripping Europe in his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace. Keynes wrote:

Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the Capitalist System was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. [...] Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.

Keynes explicitly pointed out the relationship between governments printing money and inflation.

The inflationism of the currency systems of Europe has proceeded to extraordinary lengths. The various belligerent Governments, unable, or too timid or too short-sighted to secure from loans or taxes the resources they required, have printed notes for the balance.

Keynes also pointed out how government price controls discourage production.

The presumption of a spurious value for the currency, by the force of law expressed in the regulation of prices, contains in itself, however, the seeds of final economic decay, and soon dries up the sources of ultimate supply. If a man is compelled to exchange the fruits of his labours for paper which, as experience soon teaches him, he cannot use to purchase what he requires at a price comparable to that which he has received for his own products, he will keep his produce for himself, dispose of it to his friends and neighbours as a favour, or relax his efforts in producing it. A system of compelling the exchange of commodities at what is not their real relative value not only relaxes production, but leads finally to the waste and inefficiency of barter.

Keynes detailed the relationship between German government deficits and inflation.

In Germany the total expenditure of the Empire, the Federal States, and the Communes in 1919–20 is estimated at 25 milliards of marks, of which not above 10 milliards are covered by previously existing taxation. This is without allowing anything for the payment of the indemnity. In Russia, Poland, Hungary, or Austria such a thing as a budget cannot be seriously considered to exist at all. Thus the menace of inflationism described above is not merely a product of the war, of which peace begins the cure. It is a continuing phenomenon of which the end is not yet in sight.

Keynesian in the short run, classical in the long run

While

most economists believe that changes in money supply can have some real

effects in the short run, neoclassical and neo-Keynesian economists

tend to agree that there are no long-run effects from changing the money

supply. Therefore, even economists who consider themselves

neo-Keynesians usually believe that in the long run, money is neutral.

In other words, while neoclassical and neo-Keynesian models are often

seen as competing points of view, they can also be seen as two

descriptions appropriate for different time horizons. Many mainstream

textbooks today treat the neo-Keynesian model as a more appropriate

description of the economy in the short run, when prices are 'sticky',

and treat the neoclassical model as a more appropriate description of

the economy in the long run, when prices have sufficient time to adjust

fully.

Therefore, while mainstream economists today might often

attribute short periods of stagflation (not more than a few years) to

adverse changes in supply, they would not accept this as an explanation

of very prolonged stagflation. More prolonged stagflation would be

explained as the effect of inappropriate government policies: excessive

regulation of product markets and labor markets leading to long-run

stagnation, and excessive growth of the money supply leading to long-run

inflation.

Alternative views

As differential accumulation

Political economists Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler have proposed an explanation of stagflation as part of a theory they call differential accumulation,

which says firms seek to beat the average profit and capitalisation

rather than maximise. According to this theory, periods of mergers and

acquisitions oscillate with periods of stagflation. When mergers and

acquisitions are no longer politically feasible (governments clamp down

with anti-monopoly rules), stagflation is used as an alternative to have

higher relative profit than the competition. With increasing mergers

and acquisitions, the power to implement stagflation increases.

Stagflation appears as a societal crisis, such as during the

period of the oil crisis in the 70s and in 2007 to 2010. Inflation in

stagflation, however, does not affect all firms equally. Dominant firms

are able to increase their own prices at a faster rate than competitors.

While in the aggregate no one appears to profit, differentially

dominant firms improve their positions with higher relative profits and

higher relative capitalisation. Stagflation is not due to any actual

supply shock, but because of the societal crisis that hints at a supply

crisis. It is mostly a 20th and 21st century phenomenon that has been

mainly used by the "weapondollar-petrodollar coalition" creating or

using Middle East crises for the benefit of pecuniary interests.

Demand-pull stagflation theory

Demand-pull

stagflation theory explores the idea that stagflation can result

exclusively from monetary shocks without any concurrent supply shocks or

negative shifts in economic output potential. Demand-pull theory

describes a scenario where stagflation can occur following a period of

monetary policy implementations that cause inflation. This theory was

first proposed in 1999 by Eduardo Loyo of Harvard University's John F.

Kennedy School of Government.

Supply-side theory

Supply-side economics emerged as a response to US stagflation in the 1970s. It largely attributed inflation to the ending of the Bretton Woods system

in 1971 and the lack of a specific price reference in the subsequent

monetary policies (Keynesian and Monetarism). Supply-side economists

asserted that the contraction component of stagflation resulted from an

inflation-induced rise in real tax rates.

Austrian School of economics

Adherents to the Austrian School maintain that creation of new money ex nihilo benefits the creators and early recipients of the new money relative to late recipients. Money creation

is not wealth creation; it merely allows early money recipients to

outbid late recipients for resources, goods, and services.

Since the actual producers of wealth are typically late recipients,

increases in the money supply weakens wealth formation and undermines

the rate of economic growth. Says Austrian economist Frank Shostak:

"The increase in the money supply rate of growth coupled with the

slowdown in the rate of growth of goods produced is what the increase

in the rate of price inflation is all about. (Note that a price is the

amount of money paid for a unit of a good.) What we have here is a

faster increase in price inflation and a decline in the rate of growth

in the production of goods. But this is exactly what stagflation is all

about, i.e., an increase in price inflation and a fall in real economic

growth. Popular opinion is that stagflation is totally made up. It

seems therefore that the phenomenon of stagflation is the normal outcome

of loose monetary policy. This is in agreement with [Phelps and

Friedman (PF)]. Contrary to PF, however, we maintain that stagflation is

not caused by the fact that in the short run people are fooled by the

central bank. Stagflation is the natural result of monetary pumping

which weakens the pace of economic growth and at the same time raises

the rate of increase of the prices of goods and services."

Jane Jacobs and the influence of cities on stagflation

In 1984, journalist and activist Jane Jacobs proposed the failure of major macroeconomic theories to explain stagflation was due to their focus on the nation as the salient unit of economic analysis, rather than the city.

She proposed that the key to avoiding stagflation was for a nation to

focus on the development of "import-replacing cities" that would

experience economic ups and downs at different times, providing overall

national stability and avoiding widespread stagflation. According to

Jacobs, import-replacing cities are those with developed economies that

balance their own production with domestic imports—so they can respond

with flexibility as economic supply and demand cycles change. While

lauding her originality, clarity, and consistency, urban planning

scholars have criticized Jacobs for not comparing her own ideas to those

of major theorists (e.g., Adam Smith, Karl Marx) with the same depth and breadth they developed, as well as a lack of scholarly documentation. Despite these issues, Jacobs' work is notable for having widespread public readership and influence on decision-makers.

Responses

Stagflation undermined support for the Keynesian consensus.

Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker very sharply increased interest rates from 1979–1983 in what was called a "disinflationary scenario".

After U.S. prime interest rates had soared into the double-digits,

inflation did come down; these interest rates were the highest long-term

prime interest rates that had ever existed in modern capital markets.

Volcker is often credited with having stopped at least the inflationary

side of stagflation, although the American economy also dipped into

recession. Starting in approximately 1983, growth began a recovery. Both

fiscal stimulus and money supply growth were policy at this time. A

five- to six-year jump in unemployment during the Volcker disinflation

suggests Volcker may have trusted unemployment to self-correct and

return to its natural rate within a reasonable period.

![\pi _{{t}}=\beta E_{{t}}[\pi _{{t+1}}]+\kappa y_{{t}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0ef7dd57c38352c58215d6a0a3e102a4218956f6)

![\beta E_{{t}}[\pi _{{t+1}}]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/665311ff5571a987a4e48a2435270b77aa595d37)

![\kappa ={\frac {h[1-(1-h)\beta ]}{1-h}}\gamma](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c91590f920d1dc4d17ea89f5ce58c14b50261a9a)