The African Independence Movements took place in the 20th century, when a wave of struggles for independence in European-ruled African territories were witnessed.

Notable independence movements took place:

- Algeria (former French Algeria), see Algerian War

- Angola (former Portuguese Angola), see Portuguese Colonial War

- Guinea-Bissau (former Portuguese Guinea), see Portuguese Colonial War

- Kenya (former British Kenya), see Mau Mau Uprising

- Madagascar (see Malagasy Uprising)

- Mozambique (former Portuguese Mozambique), see Portuguese Colonial War

- Namibia (former South West Africa) – against South Africa, see Namibian War of Independence and South African Border War

- Zimbabwe (former Rhodesia) – see Rhodesian Bush War

British overseas territories

British Kenya

British-ruled Kenya was the place of a rebellion from 1952 to 1960, an insurgency by Kenyan rebels against the British colonialist rule. The core of the rebellion was formed by members of the Kikuyu ethnic group, along with smaller numbers of Embu and Meru.

French overseas territories

The flag of Algeria

French Algeria

The colonization of Algeria:

French colonization of Algeria began on June 14, 1830 when French soldiers arrived in a coastal town, Sidi Ferruch.

The troops did not encounter significant resistance, and within 3

weeks, the occupation was officially declared on July 5, 1830. After a year of occupation over 3,000 Europeans (mostly French) had arrived ready to start businesses and claim land.

In reaction to the French occupation, Amir Abd Al-Qadir was elected

leader of the resistance movement. On November 27, 1832, Abd Al-Qadir

declared that he reluctantly accepted the position, but saw serving in

the position as a necessity in order to protect the country from the

enemy (the French). Abd Al-Qadir declared the war against the French as jihad, opposed to liberation.

Abd Al-Qadir's movement was unique from other independence movements

because the main call to action was for Islam rather than nationalism.

Abd Al-Qadir fought the French for nearly two decades, but was defeated

when the Tijaniyya Brotherhood agreed to submit to French rule as long

as “they were allowed to exercise freely the rites of their religion,

and the honor of their wives and daughters was respected”.

In 1847 Abd Al-Qadir was defeated and there were other resistance

movements but none of them were as large nor as effective in comparison.

Due to the lack of effective large-scale organizing, Algerian Muslims

“resorted to passive resistance or resignation, waiting for new

opportunities,” which came about from international political changes

due to World War I.

As World War I became a reality, officials discussed drafting young

Algerians into the army to fight for the French, but there was some

opposition.

European settlers were worried that if Algerians served in the army,

then those same Algerians would want rewards for their service and claim

political rights (Alghailani). Despite the opposition, the French

government drafted young Algerians into the French army for World War I.

Since many Algerians had fought as French soldiers during the First World War, just as the European settlers had suspected, Muslim

Algerians wanted political rights after serving in the war. Muslim

Algerians felt it was all the more unfair that their votes were not

equal to the other Algerians (the settler population) especially after

1947 when the Algerian Assembly was created. This assembly was composed

of 120 members. Muslim Algerians who represented about 9 million people

could designate 50% of the Assembly members while 900,000 non-Muslim

Algerians could designate the other half.

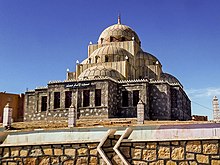

Muslim mosque in Algeria

Religion in Algeria:

When the French arrived in Algeria in 1830, they quickly took control of all Muslim establishments. The French took the land in order to transfer wealth and power to the new French settlers.

In addition to taking property relating Muslim establishments, the

French also took individuals’ property and by 1851, they had taken over

350,000 hectares of Algerian land. For many Algerians, Islam was the only way to escape the control of French Imperialism.

In the 1920s and 30s, there was an Islamic revival led by the ulama,

and this movement became the basis for opposition to French rule in

Algeria.

Ultimately, French colonial policy failed because the ulama, especially

Ibn Badis, utilized the Islamic institutions to spread their ideas of

revolution.

For example, Ibn Badis used the “networks of schools, mosques, cultural

clubs, and other institutions,” to educate others, which ultimately

made the revolution possible.

Education became an even more effective tool for spreading their

revolutionary ideals when Muslims became resistant to sending their

children to French schools, especially their daughters.

Ultimately, this led to conflict between the French and the Muslims

because there were effectively two different societies within one

country.

Monument to those killed in the first independence protest

Leading up to the fight for independence:

The fight for independence, or the Algerian war, began with a massacre that occurred on May 8, 1945 in Setif,

Algeria. After WWII ended, nationalists in Algeria, in alignment with

the American anti-colonial sentiment, organized marches, but these

marches became bloody massacres. An estimated 6,000-45,000 Algerians were killed by the French army. This event triggered a radicalization of Algerian nationalists and it was a crucial event in leading up to the Algerian War.

In response to the massacre, Messali Hadj, the leader of the

independence party, the Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties

(MTLD), "turned to electoral politics. With Hadj’s leadership, the party won multiple municipal offices. But, in the 1948 elections the candidates were arrested by Interior Minister Jules Moch.

While the candidates were being arrested, the local authorities stuffed

ballots for Muslim men, non-members of the independence party.

Since the MTLD could not gain independence via elections, Hadj turned

to violent means and consulted "the head of its parliamentary wing,

Hocine A ̈ıt Ahmed, to advise on how the party might win Algeria’s

independence through force of arms."

A ̈ıt Ahmed had never been formally trained in strategy, so he studied

former rebellions against the French and he came to the conclusion that

"no other anti-colonial movement had had to deal with such a sizable and

politically powerful settler population."

Due to the powerful settler population, A ̈ıt Ahmed believed that

Algeria could only achieve independence if the movement became relevant

in the international political arena.

Over the next few years, members of the MTLD began to disagree about

which direction the organization should go to achieve independence, so

eventually the more radical members broke off to form the National

Liberation Front (FLN).

The fight for independence in the international arena:

The FLN officially started the Algerian War for Independence and

followed A ̈ıt Ahmed's advice by creating tensions in the

Franco-American relations. Due to the intensifying global relations, the Algerian War became a "kind of world war—a war for world opinion".

In closed-door meetings the United States encouraged France to

negotiate with the FLN, but during UN meetings the United States helped

France end discussion on Algeria.

Ultimately, the strategy of just focusing on superpowers was not

successful for Algeria, but once A ̈ıt Ahmed began to exploit

international rivalries the Algerian war for independence was

successful.

Algerian women in the Algerian War of Independence

Women in the fight for independence:

Thousands of women took part in the war, even on deadly missions. Women took part as “combatants, spies, fundraisers, and couriers, as well as nurses, launderers, and cooks”. 3% of all fighters were women, which is roughly equivalent to 11,000 women.

This is a quote of three women who participated in the war: “We

had visited the site and noted several possible targets. We had been

told to place two bombs, but we were three, and at the last moment,

since it was possible, we decided to plant three bombs. Samia and I

carried three bombs from the Casbah to Bab el Oued, where they were

primed...Each of us placed a bomb, and at the appointed time there were

two explosions; one of the bombs was defective and didn’t go off.’ -

Djamila B., Zohra D., and Samia, Algiers, September 1956”.

Outcome of Independence:

Algeria gained independence on February 20, 1962 when the French government signed a peace accord.

While the women's movement made significant gains

post-independence, peace in the country did not last long. Shortly after

gaining independence, the Algerian Civil War

began. The civil war erupted from anger regarding one party rule and

ever increasing unemployment rates in Algeria. In October 1988, young

Algerian men took to the streets and participated in week-long riots.

In addition, the Algerian war for independence inspired liberationists in South Africa. However, the liberationists were unsuccessful in implementing Alergian strategy into their independence movement.

The Algerian Independence movement also had a lasting impact on

French thought about the relationship between the government and

religion.

Portuguese overseas territories

Portugal built a five-century-long global empire.

Portuguese overseas expansion began in the 15th century, thanks to

several factors that gave the small coastal nation an advantage over its

larger European neighbours. First, in the 14th century, Portuguese

shipbuilders invented several new techniques that made sailing in the

stormy Atlantic Ocean more practical. They combined elements of

different types of ships to construct stronger, roomier and more

manoeuvrable caravels. They also took advantage of more reliable compasses for navigation, and benefited from the school for navigation created by Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) at Sagres in 1419. Starting with voyages to Madeira and the Azores

(islands in the Atlantic) in the first part of the 14th century, the

Portuguese systematically extended their explorations as far as Japan by

the 16th century. In the process, they established forts and

settlements along the West and East African coasts. In the 16th through

18th centuries, the Portuguese lost their lead to other European

nations, notably England and France, but played a major role in the

slave trade to satisfy the demand for labour in Brazil

and other American markets. By the beginning of the 19th century,

Portugal controlled outposts at six locations in Africa. One was the Cape Verde Islands, located about 700 miles due west of Dakar, Senegal. Claimed for Portugal by Diogo Gomes

about 1458, this archipelago of eight major islands was devoted to

sugar cultivation using slaves taken from the African mainland. The

Portuguese once had extensive claims on the West African coast—since

they were the first Europeans to explore it systematically—but by 1800

they were left with only a few ports at the mouth of the Rio Geba in

what is now known as the Guinea-Bissau. To the east, the Portuguese controlled the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe,

located south of the mouth of the Niger River. Like the Cape Verde

Islands, they were converted to sugar production in the early 16th

century using slaves acquired on the mainland in the vicinity of the

Congo River. By the end of the 19th century, Portuguese landowners had

successfully introduced cocoa

production using forced African labour. Further south, the Portuguese

claimed both sides of the mouth of the Congo River, as well as the

Atlantic coast as far south as the Rio Cunene. In practical terms,

Portugal controlled port cities like those of Cabinda (north of the Congo River mouth), Ambriz (south of the Congo's mouth), Luanda and Benguela (on the Angolan coast) plus some river towns in the Angolan interior.

The last area claimed by Portugal in Africa was along the

southeast coast on either side of the mouth of the Zambezi River. After

reaching this area, known as the Swahili Coast, at the end of the 15th

century, the Portuguese came to dominate most of it by the end of the

16th century. During the 17th century, they lost control of everything

north of Cape Delgado to Arabs from Oman (who established the Sultanate of Zanzibar), leaving them with major ports at Mozambique, Quelimane, and Lourenço Marques, plus settlements along the Zambezi and other rivers.

Despite these holdings, the Portuguese hold in Africa was

problematic. The first cause was the small size of Portugal's

population, coupled with the lack of popular support for overseas

empire. Exploration and conquest began as an enterprise supported by the

nobility, and Portuguese peasants rarely participated unless forced to

do so. When the common people of Portugal did chose to emigrate, they

were much more likely to head to Brazil and other territories than to

Africa. To induce Europeans to move to its African holdings, the

Portuguese government resorted to releasing degradados—convicted

criminals—from prison in exchange for accepting what amounted to exile

in Africa. Angola, in particular, gained a reputation as a Portuguese

penal colony. Also, since the European population remained almost

entirely male, the Portuguese birth rate was negligible, although plenty

of "Afro-Lusitanians" were born to African mothers. As a result, the

European population of Portugal's African settlements was never very

large, and community leaders were just as likely to owe their loyalty to

local African governments as they did to the distant Portuguese

government.

A second cause of weakness in Portuguese Africa was the effects of three centuries of Atlantic slave trade which had roots in the older African slave trade.

Once the Atlantic triangular trade got underway, many Portuguese

(including many Brazilian traders) in Africa found little incentive to

engage in any other kind of profitable economic activity. The economies

of Guinea, Angola and Mozambique became almost entirely devoted to the

export of slaves to the New World

(plus gold and ivory where they were available) while on the islands,

slaves were used to grow sugar for export. Colonial authorities did

nothing to stop the slave trade, which had sympathisers even among the

several native African tribes, and many became wealthy by supporting it,

while the traders themselves generated huge profits with which they

secured allies in Africa and Portugal.

Although anti-slavery efforts became organised in Europe in the

18th century, the slave trade only came to an end in the early 19th

century, thanks in large part to English efforts to block shipping to

the French during the Napoleonic Wars. Portugal was one of the first

countries in the world to outlaw slavery, and did it so in mainland Portugal

during the 18th century. The Portuguese government ended colonial

slavery in stages with a final decree in 1858 that outlawed slavery in

the overseas empire. The gradual pace of abolition was due to the

strength of pro-slavery forces in Portuguese politics, Brazil and in

Africa, they interfered with colonial administrators who challenged

long-established and powerful commercial interests.

The Napoleonic Wars

added a new force to the Portuguese political

scene—republicanism—introduced as an alternative to the monarchy by

French troops in 1807. The French invasion induced the Portuguese royal

family to make the controversial decision to flee to Brazil (on English

ships), from where they ruled until 1821. By the time King João VI

returned to Lisbon, he faced a nobility divided in their support for

him personally, plus a middle class that wanted a constitutional

monarchy. During Joao VI's reign (1821–1826) and that of his

successors—Peter IV (1826–1831), Maria (1833–1853), Peter V (1853–1861),

Louis I (1861–1889), and Carlos (1889–1908)—there was a civil war that

lasted from 1826 to 1834, a long period characterised by what one author

called "ministerial instability and chronic insurrection" from 1834 to

1853, and finally the end of the monarchy when both Carlos and his heir

were assassinated on February 1, 1908. Under those circumstances,

colonial officials appointed by governments in Lisbon were more

concerned with politics at home than with administering their African

territories.

As it did everywhere else, the Industrial Revolution stimulated change in Portuguese Africa. It created a demand for tropical raw materials like vegetable oils, cotton, cocoa and rubber,

and it also created a need for markets to purchase the expanded

quantity of goods issuing from factories. In Portugal's case, most of

the factories were located in England, which had had a special

relationship with Portugal ever since Philippa, the daughter of England's John of Gaunt,

married John of Avis, the founder of the Portuguese second dynasty.

Prodded by Napoleon's invasion and English support for the royal

family's escape to Brazil, King João and his successors eliminated

tariffs, ended trade monopolies and generally opened the way for British

merchants to become dominant in the Portuguese empire. At times, that

caused friction, such as when both British and Portuguese explorers

claimed the Shire Highlands (located in modern Malawi),

but for the most part Great Britain supported the Portuguese position

in exchange for incorporating Portugal's holdings into the British

economic sphere.

With neither a large European population nor African wage

earners, the Portuguese colonies offered poor markets for manufactured

goods from the private sector. Consequently, industrialisation arrived

in the form of government programs designed to improve internal

communications and increase the number of European settlers. During the

late 1830s, the government headed by Marquis Sá da Bandeira

tried to encourage Portuguese farmers to migrate to Angola, with little

success. Between 1845 and 1900, the European population of Angola rose

from 1,832 to only about 9,000. European migration to Mozambique showed

slightly better results—about 11,000 in 1911—but many were British from

South Africa rather than Portuguese. The other major force for change

was the rivalries that developed between European nations in the century

between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the outbreak of World War I.

Forbidden from fighting each other by the "balance of power"

established by the Treaty of Vienna,

they competed in other ways including scientific discoveries, athletic

competitions, exploration and proxy wars. Although not a major power

anymore, Portugal participated in the competition, especially by sending

out explorers to solidify their claim to all of the land between Angola

and Mozambique. That bought them into conflict with men like Cecil Rhodes, whose own vision of an empire from "Cape to Cairo" required that the British gain control over the same land.

European rivalries appeared most often as commercial competition,

and in 19th century Africa, that included the right to move goods by

steamboat along rivers. The British had a head start thanks to their

early adoption of steam technology and their supremacy on the high seas.

They became the strongest proponents of the principle of "free trade"

which prohibited countries from creating legal barriers to another

country's merchants. Occasionally, Portuguese leaders resisted, but the

British alliance provided sufficient benefits to convince various

administrations to go along (although they faced revolts at home and in

their colonies).

It was Portugal's claim to the land on either side of the mouth of the Congo River that triggered the events leading up to the Congress of Berlin. That claim, which dated from Diogo Cão's

voyage in 1484, gave Portugal places from which naval patrols could

control access to Africa's largest river system. The British eyed this

arrangement with suspicion for years, but paid tariffs (like everyone

else) for the right to trade there, mostly for slaves.

After the abolition of slavery got underway, the Portuguese

dragged their heels, so in 1839 the British government declared its

right to inspect Portuguese ships for evidence of slave trading with or

without Portuguese consent. That stirred the Portuguese to action, and

in a subsequent series of agreements made in the 1840s, the British

acquired the right to land their ships to land where no Portuguese

authorities were present. When the Portuguese refused to renew the

agreement in 1853, the British ceased paying tariffs at the ports on

either side of the Congo River mouth, claiming that Portugal's claim had

expired because they had left the area unoccupied for too long.

Portugal reoccupied the ports of Cabinda and Ambriz in 1855, and

relations with Great Britain improved after that. The dispute set a

precedent, however, that effective occupation was a prerequisite for

recognition of colonial claims. The question continued to reappear until

1885 when it was enshrined in the agreements that emanated from the

Congress of Berlin.

The final straw was the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty signed on

February 26, 1884. It granted exclusive navigation rights on the Congo

River to Britain in exchange for British guarantees of Portugal's

control of the coast at the mouth of the Congo River. Most

significantly, it prevented the French from taking advantage of treaties

signed by one of its explorers (Savorgnan de Brazza)

with Africans living along the north side of the Congo River.

International protests forced the two countries to abandon the treaty in

June 1884, and Bismarck used the controversy to call the Congress of Berlin later that year.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to claim territory in

sub-Saharan Africa, and their example inspired imitation from other

European powers. For the British, the Portuguese were acceptable proxies

in the competition with France, Russia and Germany for world

domination. For Portuguese governments, the British alliance gave them

influence that they could not command themselves, while the idea of a

Portuguese empire offered something with which to distract domestic

opponents from the struggles initiated by the Napoleonic Wars.

The issues that were raised by Portugal's claims in Africa and

the efforts of other countries to whittle them down became the

fundamental issues of the Congress of Berlin.

In the end, the Congress settled more than the future of Portugal's

African holdings—it also set the rules for any European government which

wished to establish an empire in Africa.

In the 1950s, after World War II, several African territories

became independent from their European rulers, but the oldest

Europe-ruled territories, those ruled by Portugal, were rebranded

"Overseas Provinces" from the former designation as Portuguese colonies.

This was a firm effort of Portugal's authorities to preserve its old

African possessions abroad and refuse any claims of independence. This

was followed by a wave of strong economic and social developments in all

Portuguese Africa, in particular the overseas provinces of Angola and Mozambique.

By the 1960s, several organisations were founded to support

independence's claims of the Portuguese overseas provinces in Africa.

They were mostly entirely based and supported from outside Portugal's

territories. Headquartered and managed in countries like Senegal, Tanzania, Algeria, Guinea and Ethiopia, these guerrilla movements sought weapons, financing and political support in Eastern Bloc's communist states and the People's Republic of China. A Cold War conflict in Portuguese Africa was about to start. Marxist-Leninist and Maoist ideologies, backed by countries like the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China

were behind the nationalist guerrilla movements created to attack

Portuguese possessions and claim independence. The USA and other

countries, in order to counter communist

growing influence in the region also started to support some

nationalist guerrillas in their fight against Portugal. The series of guerrilla wars involving Portugal and several armed nationalist groups from Africa in its overseas provinces of Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique, become known as the Portuguese Colonial War (Guerra Colonial or Guerra do Ultramar).

African nationalism in Portuguese Africa

Portuguese Angola

Portuguese soldiers in Angola.

In Portuguese Angola, the rebellion of the ZSN was taken up by the União das Populações de Angola (UPA), which changed its name to the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) in 1962. On February 4, 1961, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA)

took credit for the attack on the prison of Luanda, where seven

policemen were killed. On March 15, 1961, the UPA, in a tribal attack,

started the massacre of white populations and black workers born in

other regions of Angola. This region would be retaken by large military

operations that, however, would not stop the spread of the guerrilla actions to other regions of Angola, such as Cabinda, the east, the southeast and the central plateaus.

Portuguese Guinea

PAIGC's checkpoint in 1974

In Portuguese Guinea, the Marxist African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) started fighting in January 1963. Its guerrilla fighters attacked the Portuguese headquarters in Tite, located to the south of Bissau,

the capital, near the Corubal river . Similar actions quickly spread

across the entire colony, requiring a strong response from the

Portuguese forces.

The war in Guinea placed face to face Amílcar Cabral, the leader of PAIGC, and António de Spínola,

the Portuguese general responsible for the local military operations.

In 1965 the war spread to the eastern part of the country and in that

same year the PAIGC carried out attacks in the north of the country

where at the time only the minor guerrilla movement, the Frente de Luta pela Independência Nacional da Guiné (FLING), was fighting. By that time, the PAIGC started receiving military support from the Socialist Bloc, mainly from Cuba, a support that would last until the end of the war.

In Guinea the Portuguese troops mainly took a defensive position,

limiting themselves to keeping the territories they already held. This

kind of action was particularly devastating to the Portuguese troops who

were constantly attacked by the forces of the PAIGC. They were also

demoralised by the steady growth of the influence of the liberation

supporters among the population that was being recruited in large

numbers by the PAIGC.

With some strategic changes by António Spínola in the late 1960s,

the Portuguese forces gained momentum and, taking the offensive, became

a much more effective force. Between 1968 and 1972, the Portuguese

forces took control of the situation and sometimes carried attacks

against the PAIGC positions. At this time the Portuguese forces were

also adopting subversive means to counter the insurgents, attacking the

political structure of the nationalist movement. This strategy

culminated in the assassination of Amílcar Cabral in January 1973.

Nonetheless, the PAIGC continued to fight back and pushed the Portuguese

forces to the limit. This became even more visible after PAIGC

received anti-aircraft weapons provided by the Soviets, especially the SA-7 rocket launchers, thus undermining the Portuguese air superiority.

Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique was the last territory to start the war of liberation. Its nationalist movement was led by the Marxist-Leninist Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which carried out the first attack against Portuguese targets on September 24, 1964, in Chai, province of Cabo Delgado. The fighting later spread to Niassa, Tete

at the centre of the country. A report from Battalion No. 558 of the

Portuguese army makes references to violent actions, also in Cabo

Delgado, on August 21, 1964. On November 16 of the same year, the

Portuguese troops suffered their first losses fighting in the north of

the country, in the region of Xilama. By this time, the size of the

guerrilla movement had substantially increased; this, along with the low

numbers of Portuguese troops and colonists, allowed a steady increase

in FRELIMO's strength. It quickly started moving south in the direction

of Meponda and Mandimba, linking to Tete with the aid of Malawi.

Until 1967 the FRELIMO showed less interest in Tete region,

putting its efforts on the two northernmost districts of the country

where the use of landmines

became very common. In the region of Niassa, FRELIMO's intention was

to create a free corridor to Zambézia. Until April 1970, the military

activity of FRELIMO increased steadily, mainly due to the strategic work

of Samora Machel in the region of Cabo Delgado. In the early 1970s,

after the Portuguese Gordian Knot Operation, the nationalist guerrilla was severely damaged.

Role of the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity

(OAU) was founded May 1963. Its basic principles were co-operation

between African nations and solidarity between African peoples. Another

important objective of the OAU was an end to all forms of colonialism in

Africa. This became the major objective of the organisation in its

first years and soon OAU pressure led to the situation in the Portuguese

colonies being brought up at the UN Security Council.

The OAU established a committee based in Dar es Salaam, with representatives from Ethiopia, Algeria, Uganda, Egypt, Tanzania, Zaire, Guinea, Senegal and Nigeria,

to support African liberation movements. The support provided by the

committee included military training and weapon supplies. The OAU also

took action in order to promote the international acknowledgement of the

legitimacy of the Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (GRAE),

composed of the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA). This support was transferred to the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and to its leader, Agostinho Neto

in 1967. In November 1972, both movements were recognised by the OAU in

order to promote their merger. After 1964, the OAU recognised PAIGC as

the legitimate representatives of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde and in

1965 recognised FRELIMO for Mozambique.

Eritrea

Eritrea sits on a strategic location along the Red Sea, between the Suez Canal and the Bab-el-Mandeb. Eritrea was an Italian colony from 1890–1941. On April 1, 1941, the British captured Asmara

defeating the Italians and Eritrea fell under the British Military

Administration. This military rule lasted from 1941 until 1952. On

December 2, 1950, the United Nations General Assembly, by UN Resolution

390 A(V) federated Eritrea with Ethiopia. The architect of this federal

act was the United States. The federation went into effect September 11,

1952. However, the federation was a non-starter for feudal Ethiopia,

and it started to systematically undermine it. On December 24, 1958—the

Eritrean flag was replaced by the Ethiopian flag;

On May 17, 1960—The title "Government of Eritrea" of the Federation was

changed to "Administration of Eritrea". Earlier Amharic was declared official language in Eritrea replacing Tigrinya and Arabic. Finally on November 14, 1962 -– Ethiopia officially annexed Eritrea as its 14th province.

The people of Eritrea, after finding out peaceful resistance against Ethiopia's rule was falling on deaf ears formed the Eritrean Liberation Movement

(ELM) which was formed in 1958. The founders of these independence

movement were: Mohammad Said Nawud, Saleh Ahmed Iyay, Yasin al-Gade,

Mohammad al-Hassen and Said Sabr. ELM members were organised in secret

cells of seven. The movement was known as Mahber Shewate in Tigrinya and

as Harakat Atahrir al Eritrea in Arabic. On July 10, 1960, a second

independence movement, the Eritrean Liberation Front

(ELF) was founded in Cairo. Among its founders were: Idris Mohammed

Adem, President, Osman Salih Sabbe, Secretary General, and Idris

Glawdewos as head of military affairs. These were among those who made

up the highest political body known as the Supreme Council. On September

1, 1961, Hamid Idris Awate and his ELF unit attacked an Ethiopian

police unit in western Eritrea (near Mt. Adal). This heralded the

30-year Eritrean war for independence. Between March and November 1970,

three core groups that later made up the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) split from the ELF and established themselves as separate units.

In September 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown by a

military coup in Ethiopia. The military committee that took power in

Ethiopia is better known by its Amharic name the Derg.

After the military coup the Derg broke ties with the U.S. and realigned

itself with the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) and the USSR

and its eastern bloc allies replaced America as patrons of Ethiopia's

aggression against Eritrea. Between January and July 1977, the ELF and

EPLF armies had liberated 95% of Eritrea capturing all but 4 towns.

However, in 1978–79, Ethiopia mounted a series of five massive

Soviet-backed offensives and reoccupied almost all of Eritrea's major

towns and cities, except for Nakfa. The EPLF withdrew to a mountain base

in northern Eritrea, around the town of Nakfa.

In 1980 the EPLF had offered a proposal for referendum to end the war,

however, Ethiopia, thinking it had a military upper hand, rejected the

offer and war continued. In February–June 1982, The EPLF managed to

repulse Ethiopia's much heralded four-month "Red Star" campaign (aka the

6th offensive by Eritreans) inflicting more than 31,000 Ethiopian

casualties. In 1984 the EPLF started its counter-offensive and cleared

the Ethiopian from the North-eastern Sahil front. In March 1988 the EPLF

demolished the Ethiopian front at Afabet in a major offensive the

British Historian Basil Davidson compared to the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. In February 1990 the EPLF liberated the strategic port of Massawa and in the process destroyed a portion of the Ethiopian Navy.

A year later the war came to conclusion on May 24, 1991, when the

Ethiopian army in Eritrea surrendered. Thus Eritrea's 30-year war

crowned with victory.

On May 24, 1993, after a UN-supervised referendum on April 23–25,

1993, in which the Eritrean people overwhelmingly, 99.8%, voted for

independence, Eritrea officially declared its independence and gained

international recognition.

Namibia

South African soldiers pose with a captured German flag after their successful invasion of South-West Africa in 1915.

At the onset of World War I, the Union of South Africa participated in the invasion and occupation of several Allied territories taken from the German Empire, most notably German South-West Africa and German East Africa (Tanzania). Germany's defeat forced the new Weimar Republic to cede its overseas possessions to the League of Nations as mandates. A mandate over South-West Africa was conferred upon the United Kingdom,

"for and on behalf of the government of the Union of South Africa",

which was to handle administrative affairs under the supervision of the

league. South-West Africa was classified as a "C" mandate, or a

territory whose population sparseness, small size, remoteness, and

geographic continuity to the mandatory power allowed it to be governed

as an integral part of the mandatory itself. Nevertheless, the League of

Nations obliged South Africa to promote social progress among

indigenous inhabitants, refrain from establishing military bases there,

and grant residence to missionaries of any nationality without

restriction. Article 7 of the South-West Africa mandate stated that the

consent of the league was required for any changes in the terms of the

mandate.

With regards to the local German population, the occupation was

on especially lenient terms; South Africa only repatriated civil and

military officials, along with a small handful of political

undesirables. Other German civilians were allowed to remain. In 1924 all

white South-West Africans were automatically naturalised as South

African nationals and British subjects thereof; the exception being

about 260 who lodged specific objections. In 1926 a Legislative Assembly

was created to represent German, Afrikaans, and English-speaking white

residents. Control over basic administrative matters, including

taxation, was surrendered to the new assembly, while matters pertaining

to defence and native affairs remained in the hands of an

administrator-general.

Following World War II, South-West Africa's international status after the dissolution of the League of Nations was questioned. The United Nations General Assembly

refused South Africa permission to incorporate the mandate as a fifth

province, largely due to its controversial policy of racial apartheid. At the General Assembly's request the issue was examined at the International Court of Justice.

The court ruled in 1950 that South Africa was not required to transfer

the mandate to UN trusteeship, but remained obligated to adhere to its

original terms, including the submission of annual reports on conditions

in the territory.

South African military convoy in Namibia, 1978.

Led by newly elected Afrikaner nationalist Daniel François Malan,

the South African government rejected this opinion and refused to

recognise the competence of the UN to interfere with South-West African

affairs. In 1960 Ethiopia and Liberia,

the only two other former League of Nations member states in Africa,

petitioned the Hague to rule in a binding decision that the league

mandate was still in force and to hold South Africa responsible for

failure to provide the highest material and moral welfare of black

South-West Africans. It was pointed out that nonwhite residents were

subject to all the restrictive apartheid legislation affecting nonwhites in South Africa, including confinement to reserves, colour bars in employment, pass laws,

and influx control over urban migrants. A South African attempt to

scupper proceedings by arguing that the court had no jurisdiction to

hear the case was rejected; conversely, however, the court itself ruled

that Ethiopia and Liberia did not possess the necessary legal interest

entitling them to bring the case.

In October 1966 the General Assembly declared that South Africa

had failed to fulfill its obligations as the mandatory power and had in

fact disavowed them. The mandate was unilaterally terminated on the

grounds that the UN would now assume direct responsibility for

South-West Africa. In 1967 and 1969 the UN called for South Africa's

disengagement and requested the Security Council to take measures to

oust the South African Defence Force from the territory that the General Assembly, at the request of black leaders in exile, had officially renamed Namibia. One of the greatest aggravating obstacles to eventual independence occurred when the UN also agreed to recognise the South West African People's Organization (SWAPO), then an almost exclusively Ovambo

body, as the sole authentic representative of the Namibian population.

South Africa was offended by the General Assembly's simultaneous

dismissal of its various internal Namibian parties as puppets of the

occupying power. Furthermore, SWAPO espoused a militant platform which

called for independence through UN activity, including military

intervention.

By 1965 SWAPO's morale had been elevated by the formation of a guerrilla wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), which forced the deployment of South African Police

troops along the long and remote northern frontier. The first armed

clashes between PLAN cadres and local security forces took place in

August 1966.