Know Nothing

| |

|---|---|

Uncle Sam's youngest son, Citizen Know Nothing, an 1854 print

| |

| Other name | Native American Party American Party |

| First Leader | Lewis Charles Levin |

| Founded | 1844 |

| Dissolved | 1860 |

| Preceded by | Whig Party |

| Succeeded by | Constitutional Union Party |

| Headquarters | New York City |

| Secret wing | Order of the Star Spangled Banner |

| Ideology | American nationalism Anti-Catholicism Nativism Republicanism Right-wing populism White nationalism |

| Religion | Protestantism colors= Red White Blue |

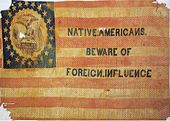

The Know Nothing movement, formally known as the Native American Party, and the American Party from 1855 onwards, was a nativist political party and movement in the United States, which operated nationwide in the mid-1850s. It was primarily an anti-Catholic, anti-immigration, and xenophobic movement, originally starting as a secret society. The Know Nothing movement also briefly emerged as a major political party in the form of the American Party. Adherents to the movement were to simply reply "I know nothing" when asked about its specifics by outsiders, providing the group with its common name.

Supporters of the Know Nothing movement believed that an alleged "Romanist" conspiracy was being planned to subvert civil and religious liberty in the United States, and sought to politically organize native-born Protestants in what they described as a defense of their traditional religious and political values. The Know Nothing movement is remembered for this theme because of fears by Protestants that Catholic priests and bishops would control a large bloc of voters. In most places, the ideology and influence of the Know Nothing movement lasted only a year or two before disintegrating due to weak and inexperienced local leaders, a lack of publicly declared national leaders, and a deep split over the issue of slavery. In the South, the party did not emphasize anti-Catholicism as frequently as it did in the North, but it became the main alternative to the dominant Democratic Party.

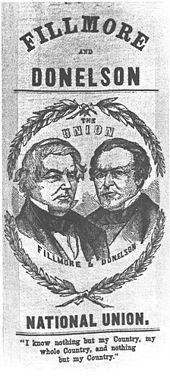

The collapse of the Whig Party after the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act left an opening for the emergence of a new major political party in opposition to the Democratic Party. The Know Nothing movement managed to elect congressman Nathaniel P. Banks of Massachusetts and several other individuals in the 1854 elections into office, and subsequently coalesced into a new political party known as the American Party. Particularly in the South, the American Party served as a vehicle for politicians opposed to the Democrats. Many also hoped that it would stake out a middle ground between the pro-slavery positions of Democratic politicians and the radical anti-slavery positions of the rapidly emerging Republican Party. The American Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore in the 1856 presidential election, although he kept quiet about his membership, and personally refrained from supporting the Know Nothing movement's activities and ideology. Fillmore received 21.5% of the popular vote in the 1856 presidential election, finishing behind the Democratic and Republican nominees.

The party entered a period of rapid decline after Millard Fillmore's loss in the 1856 election, and the controversial Dred Scott v. Sandford decision made by the Supreme Court in 1857 further galvanized opposition to slavery in the North, causing many former Know Nothings to join the Republicans. Most of the remaining members of the party supported the Constitutional Union Party in the 1860 presidential election, which subsequently lost to Abraham Lincoln of the Republican Party, and said defeat ultimately led to the final dissolution of the Know Nothing movement that same year.

History

Anti-Catholicism

had been a factor in colonial America but played a minor role in

American politics until the arrival of large numbers of Irish and German

Catholics in the 1840s.

It then reemerged in nativist attacks on Catholic immigration. It

appeared in New York City politics as early as 1843 under the banner of

the American Republican Party.

The movement quickly spread to nearby states using that name or Native

American Party or variants of it. They succeeded in a number of local

and Congressional elections, notably in 1844 in Philadelphia, where the

anti-Catholic orator Lewis Charles Levin,

who went on to be the first Jewish congressman, was elected

Representative from Pennsylvania's 1st district. In the early 1850s,

numerous secret orders grew up, of which the Order of United Americans and the Order of the Star Spangled Banner

came to be the most important. They emerged in New York in the early

1850s as a secret order that quickly spread across the North, reaching

non-Catholics, particularly those who were lower middle class or skilled

workmen.

Name

The name

"Know Nothing" originated in the semi-secret organization of the party.

When a member was asked about his activities, he was supposed to reply,

"I know nothing." Outsiders derisively called them "Know Nothings", and

the name stuck. In 1855, the Know Nothings first entered politics under

the American Party label.

Underlying issues

The

immigration of large numbers of Irish and German Catholics to the

United States in the period between 1830 and 1860 made religious

differences between Catholics and Protestants a political issue.

Violence occasionally erupted at the polls. Protestants alleged that

Pope Pius IX had put down the failed liberal Revolutions of 1848 and that he was an opponent of liberty, democracy and republicanism.

One Boston minister described Catholicism as "the ally of tyranny, the

opponent of material prosperity, the foe of thrift, the enemy of the

railroad, the caucus, and the school". These fears encouraged conspiracy theories

regarding papal intentions of subjugating the United States through a

continuing influx of Catholics controlled by Irish bishops obedient to

and personally selected by the Pope.

In 1849, an oath-bound secret society, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner,

was created by Charles B. Allen in New York City. At its inception, the

Order of the Star Spangled Banner only had about 36 members. Fear of Catholic immigration led to a dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party,

whose leadership in many cities included Catholics of Irish descent.

Activists formed secret groups, coordinating their votes and throwing

their weight behind candidates sympathetic to their cause:

Immigration during the first five years of the 1850s reached a level five times greater than a decade earlier. Most of the new arrivals were poor Catholic peasants or laborers from Ireland and Germany who crowded into the tenements of large cities. Crime and welfare costs soared. Cincinnati's crime rate, for example, tripled between 1846 and 1853 and its murder rate increased sevenfold. Boston's expenditures for poor relief rose threefold during the same period.

— James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 131

Rise

In spring

1854, the Know Nothings carried Boston and Salem, Massachusetts, and

other New England cities. They swept the state of Massachusetts in the

fall 1854 elections, their biggest victory. The Whig candidate for mayor of Philadelphia, editor Robert T. Conrad,

was soon revealed as a Know Nothing as he promised to crack down on

crime, close saloons on Sundays and to appoint only native-born

Americans to office—he won by a landslide. In Washington, D.C., Know

Nothing candidate John T. Towers defeated incumbent Mayor John Walker Maury, causing opposition of such proportion that the Democrats, Whigs, and Freesoilers

in the capital united as the "Anti-Know-Nothing Party". In New York, in

a four-way race the Know Nothing candidate ran third with 26%. After

the 1854 elections, they exerted decisive influence in Maine, Indiana,

Pennsylvania, and California, but historians are unsure about the

accuracy of this information due to the secrecy of the party, as all

parties were in turmoil and the anti-slavery and prohibition issues overlapped with nativism in complex and confusing ways. They helped elect Stephen Palfrey Webb as mayor of San Francisco and J. Neely Johnson as governor of California. Nathaniel P. Banks

was elected to Congress as a Know Nothing candidate, but after a few

months he aligned with Republicans. A coalition of Know Nothings,

Republicans and other members of Congress opposed to the Democratic Party elected Banks to the position of Speaker of the House.

The results of the 1854 elections were so favorable to the Know

Nothings, up to then an informal movement with no centralized

organization, that they formed officially as a political party called

the American Party, which attracted many members of the now nearly

defunct Whig

party as well as a significant number of Democrats. Membership in the

American Party increased dramatically, from 50,000 to an estimated one

million plus in a matter of months during that year.

The historian Tyler Anbinder concluded:

The key to Know Nothing success in 1854 was the collapse of the second party system, brought about primarily by the demise of the Whig Party. The Whig Party, weakened for years by internal dissent and chronic factionalism, was nearly destroyed by the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Growing anti-party sentiment, fueled by anti-slavery sentiment as well as temperance and nativism, also contributed to the disintegration of the party system. The collapsing second party system gave the Know Nothings a much larger pool of potential converts than was available to previous nativist organizations, allowing the Order to succeed where older nativist groups had failed.

In San Francisco,

a Know Nothing chapter was founded in 1854 to oppose Chinese

immigration—members included a judge of the state supreme court, who

ruled that no Chinese person could testify as a witness against a white

man in court.

In the spring of 1855, Know Nothing candidate Levi Boone

was elected mayor of Chicago and barred all immigrants from city jobs.

Abraham Lincoln was strongly opposed to the principles of the Know

Nothing movement, but did not denounce it publicly because he needed the

votes of its membership to form a successful anti-slavery coalition in

Illinois.

Ohio was the only state where the party gained strength in 1855. Their

Ohio success seems to have come from winning over immigrants, especially

German-American Lutherans and Scots-Irish Presbyterians, both hostile

to Catholicism. In Alabama, Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs,

discontented Democrats and other political outsiders who favored state

aid to build more railroads. Virginia attracted national attention in

its tempestuous 1855 gubernatorial election. Democrat Henry Alexander Wise

won by convincing state voters that Know Nothings were in bed with

Northern abolitionists. With the victory by Wise, the movement began to

collapse in the South.

Know Nothings scored victories in Northern state elections in

1854, winning control of the legislature in Massachusetts and polling

40% of the vote in Pennsylvania. Although most of the new immigrants

lived in the North, resentment and anger against them was national and

the American Party initially polled well in the South, attracting the

votes of many former southern Whigs.

The party name gained wide but brief popularity. Nativism became a

new American rage: Know Nothing candy, Know Nothing tea, and Know

Nothing toothpicks appeared. Stagecoaches were dubbed "The Know

Nothing". In Trescott, Maine, a shipowner dubbed his new 700-ton freighter Know Nothing. The party was occasionally referred to, contemporaneously, in a slightly pejorative shortening, "Knism."

Leadership and legislation

Historian

John Mulkern has examined the party's success in sweeping to almost

complete control of the Massachusetts legislature after its 1854

landslide victory. He finds the new party was populist and highly

democratic, hostile to wealth, elites and to expertise, and deeply

suspicious of outsiders, especially Catholics. The new party's voters

were concentrated in the rapidly growing industrial towns, where Yankee

workers faced direct competition with new Irish immigrants. Whereas the

Whig Party was strongest in high income districts, the Know Nothing

electorate was strongest in the poor districts. They expelled the

traditional upper-class, closed, political leadership, especially the

lawyers and merchants. In their stead, they elected working class men,

farmers and a large number of teachers and ministers. Replacing the

moneyed elite were men who seldom owned $10,000 in property.

Nationally, the new party leadership showed incomes, occupation,

and social status that were about average. Few were wealthy, according

to detailed historical studies of once-secret membership rosters. Fewer

than 10% were unskilled workers who might come in direct competition

with Irish laborers. They enlisted few farmers, but on the other hand

they included many merchants and factory owners.

The party's voters were by no means all native-born Americans, for it

won more than a fourth of the German and British Protestants in numerous

state elections. It especially appealed to Protestants such as the

Lutherans, Dutch Reformed and Presbyterians.

The most aggressive and innovative legislation came out of

Massachusetts, where the new party controlled all but three of the 400

seats—only 35 had any previous legislative experience. The Massachusetts

legislature in 1855 passed a series of reforms that "burst the dam

against change erected by party politics, and released a flood of

reforms." Historian Stephen Taylor says:

[In addition to nativist legislation], the party also distinguished itself by its opposition to slavery, support for an expansion of the rights of women, regulation of industry, and support of measures designed to improve the status of working people.

It passed legislation to regulate railroads, insurance companies and

public utilities. It funded free textbooks for the public schools and

raised the appropriations for local libraries and for the school for the

blind. Purification of Massachusetts against divisive social evils was a

high priority. The legislature set up the state's first reform school

for juvenile delinquents while trying to block the importation of

supposedly subversive government documents and academic books from

Europe. It upgraded the legal status of wives, giving them more property

rights and more rights in divorce courts. It passed harsh penalties on

speakeasies, gambling houses and bordellos. It passed prohibition

legislation with penalties that were so stiff—such as six months in

prison for serving one glass of beer—that juries refused to convict

defendants. Many of the reforms were quite expensive; state spending

rose 45% on top of a 50% hike in annual taxes on cities and towns. This

extravagance angered the taxpayers, and few Know Nothings were

reelected.

The highest priority included attacks on the civil rights of

Irish Catholic immigrants. After this, state courts lost the power to

process applications for citizenship and public schools had to require

compulsory daily reading of the Protestant Bible (which the nativists

were sure would transform the Catholic children). The governor disbanded

the Irish militias and replaced Irish holding state jobs with

Protestants. It failed to reach the two-thirds vote needed to pass a

state constitutional amendment to restrict voting and office holding to

men who had resided in Massachusetts for at least 21 years. The

legislature then called on Congress to raise the requirement for

naturalization from five years to 21 years, but Congress never acted.

The most dramatic move by the Know Nothing legislature was to appoint

an investigating committee designed to prove widespread sexual

immorality underway in Catholic convents. The press had a field day

following the story, especially when it was discovered that the key

reformer was using committee funds to pay for a prostitute. The

legislature shut down its committee, ejected the reformer, and saw its

investigation become a laughing stock.

The Know Nothings also dominated politics in Rhode Island, where in 1855 William W. Hoppin held the governorship and five out of every seven votes went to the party, which dominated the Rhode Island legislature. Local newspapers such as The Providence Journal fueled anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment.

Violence

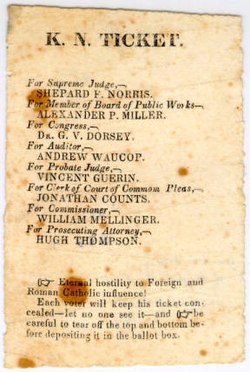

Know

Nothing Party ticket naming party candidates for state and county

offices (at the bottom of the page are voting instructions)

Fearful that Catholics were flooding the polls with non-citizens, local activists threatened to stop them.

On 6 August 1855, rioting broke out in Louisville, Kentucky, during a hotly contested race for the office of governor. Twenty-two were killed and many injured. This "Bloody Monday" riot was not the only violent riot between Know Nothings and Catholics in 1855. In Baltimore, the mayoral elections of 1856, 1857, and 1858 were all marred by violence and well-founded accusations of ballot-rigging. In the coastal town of Ellsworth Maine in 1854, Know Nothings were associated with the tarring and feathering of a Catholic priest, Jesuit Johannes Bapst. They also burned down a Catholic church in Bath, Maine.

South

In the

Southern United States, the American Party was composed chiefly of

ex-Whigs looking for a vehicle to fight the dominant Democratic Party

and worried about both the pro-slavery extremism of the Democrats and

the emergence of the anti-slavery Republican party in the North.

In the South as a whole, the American Party was strongest among former

Unionist Whigs. States-rightist Whigs shunned it, enabling the Democrats

to win most of the South. Whigs supported the American Party because of

their desire to defeat the Democrats, their unionist sentiment, their

anti-immigrant attitudes and the Know Nothing neutrality on the slavery

issue.

David T. Gleeson notes that many Irish Catholics in the South

feared the arrival of the Know-Nothing movement portended a serious

threat. He argues:

The southern Irish, who had seen the dangers of Protestant bigotry in Ireland, had the distinct feeling that the Know-Nothings were an American manifestation of that phenomenon. Every migrant, no matter how settled or prosperous, also worried that this virulent strain of nativism threatened his or her hard-earned gains in the South and integration into its society. Immigrants fears were unjustified, however, because the national debate over slavery and its expansion, not nativism or anti-Catholicism, was the major reason for Know-Nothing success in the South. The southerners who supported the Know-Nothings did so, for the most part, because they thought the Democrats who favored the expansion of slavery might break up the Union.

In 1855, the American Party challenged the Democrats' dominance. In

Alabama, the Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs, malcontented

Democrats and other political misfits; they favored state aid to build

more railroads. In the fierce campaign, the Democrats argued that Know

Nothings could not protect slavery from Northern abolitionists. The Know

Nothing American Party disintegrated soon after losing in 1855.

In Louisiana and Maryland, the Know Nothings enlisted native-born Catholics. Know Nothing congressman John Edward Bouligny

was the only member of the Louisiana congressional delegation to refuse

to resign his seat after the state seceded from the Union. In Maryland, the party's influence lasted at least through the Civil War: the American Party's Governor and later Senator Thomas Holliday Hicks, Representative Henry Winter Davis, and Senator Anthony Kennedy, with his brother, former Representative John Pendleton Kennedy, all supported the United States in a State that bordered the Confederate states.

Historian Michael F. Holt argues that "Know Nothingism originally grew

in the South for the same reasons it spread in the North—nativism,

anti-Catholicism, and animosity toward unresponsive politicos—not

because of conservative Unionism". Holt cites William B. Campbell,

former governor of Tennessee, who wrote in January 1855: "I have been

astonished at the widespread feeling in favor of their principles—to

wit, Native Americanism and anti-Catholicism—it takes everywhere".

Decline

Results by county indicating the percentage for Fillmore in each county

The party declined rapidly in the North after 1855. In the presidential election of 1856, it was bitterly divided over slavery. The main faction supported the ticket of presidential nominee Millard Fillmore and vice presidential nominee Andrew Jackson Donelson. Fillmore, a former President, had been a Whig and Donelson was the nephew of Democratic President Andrew Jackson,

so the ticket was designed to appeal to loyalists from both major

parties, winning 23% of the popular vote and carrying one state,

Maryland, with eight electoral votes. Fillmore did not win enough votes

to block Democrat James Buchanan

from the White House. During this time, Nathaniel Banks decided he was

not as strongly for the anti-immigrant platform as the party wanted him

to be, so he left the Know Nothing Party for the more anti-slavery

Republican Party. He contributed to the decline of the Know Nothing

Party by taking two-thirds of its members with him.

Many were appalled by the Know Nothings. Abraham Lincoln expressed his own disgust with the political party in a private letter to Joshua Speed, written 24 August 1855. Lincoln never publicly attacked the Know Nothings, whose votes he needed:

I am not a Know-Nothing—that is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that "all men are created equal." We now practically read it "all men are created equal, except negroes." When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read "all men are created equals, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics." When it comes to that I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

Historian Allan Nevins,

writing about the turmoil preceding the American Civil War, states that

Millard Fillmore was never a Know Nothing nor a nativist. Fillmore was

out of the country when the presidential nomination came and had not

been consulted about running. Nevins further states:

[Fillmore] was not a member of the party; he had never attended an American [Know-Nothing] gathering. By no spoken or written word had he indicated a subscription to American [Party] tenets.

After the Supreme Court's controversial Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling in 1857, most of the anti-slavery members of the American Party joined the Republican Party. The pro-slavery wing of the American Party remained strong on the local and state levels in a few southern states, but by the 1860 election they were no longer a serious national political movement. Most of their remaining members supported the Constitutional Union Party in 1860.