| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈmoʊrfiːn/ |

| Trade names | Statex, MSContin, Oramorph, Sevredol, and others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High |

| Addiction liability | High |

| Routes of administration | Inhalation (smoking), insufflation (snorting), by mouth (PO), rectal, subcutaneous (SC), intramuscular (IM), intravenous (IV), epidural, and intrathecal (IT) |

| Drug class | opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20–40% (by mouth), 36–71% (rectally), 100% (IV/IM) |

| Protein binding | 30–40% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic 90% |

| Onset of action | 5 minutes (IV), 15 minutes (IM), 20 minutes (PO) |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours |

| Duration of action | 3–7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal 90%, biliary 10% |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.291 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

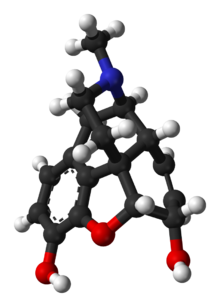

| Formula | C17H19NO3 |

| Molar mass | 285.343 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | HCl & sulf.: 60 mg/mL (20 °C) |

Morphine is a pain medication of the opiate family that is found naturally in a dark brown, resinous form from poppy plant (Papaver somniferum). It acts directly on the central nervous system (CNS) to decrease the feeling of pain. It can be taken for both acute pain and chronic pain and is frequently used for pain from myocardial infarction, kidney stones, and during labor. Morphine can be administered by mouth, by injection into a muscle, by injection under the skin, intravenously, injection into the space around the spinal cord, or rectally. Its maximum effect is reached after about 20 minutes when administered intravenously and 60 minutes when administered by mouth, while the duration of its effect is 3–7 hours. Long-acting formulations of morphine also exist.

Potentially serious side effects of morphine include decreased respiratory effort, vomiting, nausea, and low blood pressure. Morphine is addictive and prone to abuse. If one's dose is reduced after long-term use, opioid withdrawal symptoms may occur. Common side effects of morphine include drowsiness, vomiting, and constipation. Caution is advised for use of morphine during pregnancy or breast feeding, as it may affect the health of the baby.

Morphine was first isolated between 1803 and 1805 by German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner. This is generally believed to be the first isolation of an active ingredient from a plant. Merck began marketing it commercially in 1827. Morphine was more widely used after the invention of the hypodermic syringe in 1853–1855. Sertürner originally named the substance morphium, after the Greek god of dreams, Morpheus, as it has a tendency to cause sleep.

The primary source of morphine is isolation from poppy straw of the opium poppy. In 2013, approximately 523 tons of morphine were produced. Approximately 45 tons were used directly for pain, a four-fold increase over the last twenty years. Most use for this purpose was in the developed world. About 70 percent of morphine is used to make other opioids such as hydromorphone, oxymorphone, and heroin. It is a Schedule II drug in the United States, Class A in the United Kingdom, and Schedule I in Canada. It is also on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. Morphine is sold under many trade names. In 2018, it was the 132nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 5 million prescriptions.

Medical uses

Pain

Morphine is used primarily to treat both acute and chronic severe pain. Its duration of analgesia is about three to seven hours. Side-effects of nausea and constipation are rarely severe enough to warrant stopping treatment.

It is used for pain due to myocardial infarction and for labor pains. However, concerns exist that morphine may increase mortality in the event of non ST elevation myocardial infarction. Morphine has also traditionally been used in the treatment of acute pulmonary edema. A 2006 review, though, found little evidence to support this practice. A 2016 Cochrane review concluded that morphine is effective in relieving cancer pain.

Shortness of breath

Morphine is beneficial in reducing the symptom of shortness of breath due to both cancer and noncancer causes. In the setting of breathlessness at rest or on minimal exertion from conditions such as advanced cancer or end-stage cardiorespiratory diseases, regular, low-dose sustained-release morphine significantly reduces breathlessness safely, with its benefits maintained over time.

Opioid use disorder

Morphine is also available as a slow-release formulation for opiate substitution therapy (OST) in Austria, Germany, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Canada for addicts who cannot tolerate either methadone or buprenorphine.

Contraindications

Relative contraindications to morphine include:

- respiratory depression when appropriate equipment is not available

- Although it has previously been thought that morphine was contraindicated in acute pancreatitis, a review of the literature shows no evidence for this.

Adverse effects

- Common and short term

- Itchiness

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Constipation

- Drowsiness

- Dry mouth

- Respiratory depression

- Itching

- Other

- Opioid dependence

- Dizziness

- Decreased sex drive

- Loss of appetite

- Impaired sexual function

- Decreased testosterone levels

- Depression

- Immunodeficiency

- Opioid-induced abnormal pain sensitivity

- Irregular menstruation

- Increased risk of falls

- Slowed breathing

- Hallucinations

Constipation

Like loperamide and other opioids, morphine acts on the myenteric plexus in the intestinal tract, reducing gut motility, causing constipation. The gastrointestinal effects of morphine are mediated primarily by μ-opioid receptors in the bowel. By inhibiting gastric emptying and reducing propulsive peristalsis of the intestine, morphine decreases the rate of intestinal transit. Reduction in gut secretion and increased intestinal fluid absorption also contribute to the constipating effect. Opioids also may act on the gut indirectly through tonic gut spasms after inhibition of nitric oxide generation. This effect was shown in animals when a nitric oxide precursor, L-arginine, reversed morphine-induced changes in gut motility.

Hormone imbalance

Clinical studies consistently conclude that morphine, like other opioids, often causes hypogonadism and hormone imbalances in chronic users of both sexes. This side effect is dose-dependent and occurs in both therapeutic and recreational users. Morphine can interfere with menstruation in women by suppressing levels of luteinizing hormone. Many studies suggest the majority (perhaps as many as 90%) of chronic opioid users have opioid-induced hypogonadism. This effect may cause the increased likelihood of osteoporosis and bone fracture observed in chronic morphine users. Studies suggest the effect is temporary. As of 2013, the effect of low-dose or acute use of morphine on the endocrine system is unclear.

Effects on human performance

Most reviews conclude that opioids produce minimal impairment of human performance on tests of sensory, motor, or attentional abilities. However, recent studies have been able to show some impairments caused by morphine, which is not surprising, given that morphine is a central nervous system depressant. Morphine has resulted in impaired functioning on critical flicker frequency (a measure of overall CNS arousal) and impaired performance on the Maddox wing test (a measure of the deviation of the visual axes of the eyes). Few studies have investigated the effects of morphine on motor abilities; a high dose of morphine can impair finger tapping and the ability to maintain a low constant level of isometric force (i.e. fine motor control is impaired), though no studies have shown a correlation between morphine and gross motor abilities.

In terms of cognitive abilities, one study has shown that morphine may have a negative impact on anterograde and retrograde memory, but these effects are minimal and transient. Overall, it seems that acute doses of opioids in non-tolerant subjects produce minor effects in some sensory and motor abilities, and perhaps also in attention and cognition. It is likely that the effects of morphine will be more pronounced in opioid-naive subjects than chronic opioid users.

In chronic opioid users, such as those on Chronic Opioid Analgesic Therapy (COAT) for managing severe, chronic pain, behavioural testing has shown normal functioning on perception, cognition, coordination and behaviour in most cases. One 2000 study analysed COAT patients to determine whether they were able to safely operate a motor vehicle. The findings from this study suggest that stable opioid use does not significantly impair abilities inherent in driving (this includes physical, cognitive and perceptual skills). COAT patients showed rapid completion of tasks that require the speed of responding for successful performance (e.g., Rey Complex Figure Test) but made more errors than controls. COAT patients showed no deficits in visual-spatial perception and organization (as shown in the WAIS-R Block Design Test) but did show impaired immediate and short-term visual memory (as shown on the Rey Complex Figure Test – Recall). These patients showed no impairments in higher-order cognitive abilities (i.e., planning). COAT patients appeared to have difficulty following instructions and showed a propensity toward impulsive behaviour, yet this did not reach statistical significance. It is important to note that this study reveals that COAT patients have no domain-specific deficits, which supports the notion that chronic opioid use has minor effects on psychomotor, cognitive, or neuropsychological functioning.

Reinforcement disorders

Addiction

Morphine is a highly addictive substance. In controlled studies comparing the physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine in individuals formerly addicted to opiates, subjects showed no preference for one drug over the other. Equipotent, injected doses had comparable action courses, with no difference in subjects' self-rated feelings of euphoria, ambition, nervousness, relaxation, drowsiness, or sleepiness. Short-term addiction studies by the same researchers demonstrated that tolerance developed at a similar rate to both heroin and morphine. When compared to the opioids hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and pethidine/meperidine, former addicts showed a strong preference for heroin and morphine, suggesting that heroin and morphine are particularly susceptible to abuse and addiction. Morphine and heroin were also much more likely to produce euphoria and other positive subjective effects when compared to these other opioids. The choice of heroin and morphine over other opioids by former drug addicts may also be because heroin (also known as morphine diacetate, diamorphine, or diacetyl morphine) is an ester of morphine and a morphine prodrug, essentially meaning they are identical drugs in vivo. Heroin is converted to morphine before binding to the opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, where morphine causes the subjective effects, which is what the addicted individuals are seeking.

Tolerance

Several hypotheses are given about how tolerance develops, including opioid receptor phosphorylation (which would change the receptor conformation), functional decoupling of receptors from G-proteins (leading to receptor desensitization), μ-opioid receptor internalization or receptor down-regulation (reducing the number of available receptors for morphine to act on), and upregulation of the cAMP pathway (a counterregulatory mechanism to opioid effects) (For a review of these processes, see Koch and Hollt.) CCK might mediate some counter-regulatory pathways responsible for opioid tolerance. CCK-antagonist drugs, specifically proglumide, have been shown to slow the development of tolerance to morphine.

Dependence and withdrawal

Cessation of dosing with morphine creates the prototypical opioid withdrawal syndrome, which, unlike that of barbiturates, benzodiazepines, alcohol, or sedative-hypnotics, is not fatal by itself in otherwise healthy people.

Acute morphine withdrawal, along with that of any other opioid, proceeds through a number of stages. Other opioids differ in the intensity and length of each, and weak opioids and mixed agonist-antagonists may have acute withdrawal syndromes that do not reach the highest level. As commonly cited, they are:

- Stage I, 6 h to 14 h after last dose: Drug craving, anxiety, irritability, perspiration, and mild to moderate dysphoria

- Stage II, 14 h to 18 h after last dose: Yawning, heavy perspiration, mild depression, lacrimation, crying, headaches, runny nose, dysphoria, also intensification of the above symptoms, "yen sleep" (a waking trance-like state)

- Stage III, 16 h to 24 h after last dose: Rhinorrhea (runny nose) and increase in other of the above, dilated pupils, piloerection (goose bumps – a purported origin of the phrase, 'cold turkey,' but in fact the phrase originated outside of drug treatment), muscle twitches, hot flashes, cold flashes, aching bones and muscles, loss of appetite, and the beginning of intestinal cramping

- Stage IV, 24 h to 36 h after last dose: Increase in all of the above including severe cramping and involuntary leg movements ("kicking the habit" also called restless leg syndrome), loose stool, insomnia, elevation of blood pressure, moderate elevation in body temperature, increase in frequency of breathing and tidal volume, tachycardia (elevated pulse), restlessness, nausea

- Stage V, 36 h to 72 h after last dose: Increase in the above, fetal position, vomiting, free and frequent liquid diarrhea, which sometimes can accelerate the time of passage of food from mouth to out of system, weight loss of 2 kg to 5 kg per 24 h, increased white cell count, and other blood changes

- Stage VI, after completion of above: Recovery of appetite and normal bowel function, beginning of transition to postacute and chronic symptoms that are mainly psychological, but may also include increased sensitivity to pain, hypertension, colitis or other gastrointestinal afflictions related to motility, and problems with weight control in either direction

In advanced stages of withdrawal, ultrasonographic evidence of pancreatitis has been demonstrated in some patients and is presumably attributed to spasm of the pancreatic sphincter of Oddi.

The withdrawal symptoms associated with morphine addiction are usually experienced shortly before the time of the next scheduled dose, sometimes within as early as a few hours (usually 6 h to 12 h) after the last administration. Early symptoms include watery eyes, insomnia, diarrhea, runny nose, yawning, dysphoria, sweating, and in some cases a strong drug craving. Severe headache, restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, body aches, severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, tremors, and even stronger and more intense drug craving appear as the syndrome progresses. Severe depression and vomiting are very common. During the acute withdrawal period, systolic and diastolic blood pressures increase, usually beyond premorphine levels, and heart rate increases, which have potential to cause a heart attack, blood clot, or stroke.

Chills or cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey") alternating with flushing (hot flashes), kicking movements of the legs ("kicking the habit") and excessive sweating are also characteristic symptoms. Severe pains in the bones and muscles of the back and extremities occur, as do muscle spasms. At any point during this process, a suitable narcotic can be administered that will dramatically reverse the withdrawal symptoms. Major withdrawal symptoms peak between 48 h and 96 h after the last dose and subside after about 8 to 12 days. Sudden withdrawal by heavily dependent users who are in poor health is very rarely fatal. Morphine withdrawal is considered less dangerous than alcohol, barbiturate, or benzodiazepine withdrawal.

The psychological dependence associated with morphine addiction is complex and protracted. Long after the physical need for morphine has passed, the addict will usually continue to think and talk about the use of morphine (or other drugs) and feel strange or overwhelmed coping with daily activities without being under the influence of morphine. Psychological withdrawal from morphine is usually a very long and painful process. Addicts often suffer severe depression, anxiety, insomnia, mood swings, amnesia (forgetfulness), low self-esteem, confusion, paranoia, and other psychological disorders. Without intervention, the syndrome will run its course, and most of the overt physical symptoms will disappear within 7 to 10 days including psychological dependence. A high probability of relapse exists after morphine withdrawal when neither the physical environment nor the behavioral motivators that contributed to the abuse have been altered. Testimony to morphine's addictive and reinforcing nature is its relapse rate. Abusers of morphine (and heroin) have one of the highest relapse rates among all drug users, ranging up to 98% in the estimation of some medical experts.

Toxicity

| Properties of Morphine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molar mass | 285.338 g/mol | ||||

| Acidity (pKa) |

| ||||

| Solubility | 0.15 g/L at 20 °C | ||||

| Melting point | 255 °C | ||||

| Boiling point | 190 °C sublimes | ||||

A large overdose can cause asphyxia and death by respiratory depression if the person does not receive medical attention immediately.[53] Overdose treatment includes the administration of naloxone. The latter completely reverses morphine's effects, but may result in immediate onset of withdrawal in opiate-addicted subjects. Multiple doses may be needed.

The LD50 for humans of morphine sulphate and other preparations is not known with certainty. One poor quality study on morphine overdoses among soldiers reported that the fatal dose was 0.78 mcg/ml in males (~71 mg for an average 90 kg adult man) and 0.98mcg/ml in females (~74 mg for an average 75 kg female). It was not specified whether the dose was oral, parenteral or IV. Laboratory animal studies are usually cited in the literature. In serious drug dependency (high tolerance), 2000–3000 mg per day can be tolerated.

Pharmacology

Morphine has classically been divided in two classes, where class I (also known as "Morphine base") is a brown non-water-soluble powder made of concentrated opium and class II, after a chemical process, becomes a white water-soluble powder. (Some custom services around the world also defined brown Heroin as Morphine class III and the white water-soluble Heroin as Morphine class IV. As a legally permitted medicine only of the old Morphine class II is in use.

Pharmacodynamics

| Compound | Affinities (Ki) | Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | DOR | KOR | MOR:DOR:KOR | ||

| Morphine | 1.8 nM | 90 nM | 317 nM | 1:50:176 |

|

| (−)-Morphine | 1.24 nM | 145 nM | 23.4 nM | 1:117:19 |

|

| (+)-Morphine | >10 μM | >100 μM | >300 μM | ND |

|

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Codeine | PO | 200 mg |

| Hydrocodone | PO | 20–30 mg |

| Hydromorphone | PO | 7.5 mg |

| Hydromorphone | IV | 1.5 mg |

| Morphine | PO | 30 mg |

| Morphine | IV | 10 mg |

| Oxycodone | PO | 20 mg |

| Oxycodone | IV | 10 mg |

| Oxymorphone | PO | 10 mg |

| Oxymorphone | IV | 1 mg |

Morphine is the prototypical opioid and is the standard against which other opioids are tested. It interacts predominantly with the μ–δ-opioid (Mu-Delta) receptor heteromer. The μ-binding sites are discretely distributed in the human brain, with high densities in the posterior amygdala, hypothalamus, thalamus, nucleus caudatus, putamen, and certain cortical areas. They are also found on the terminal axons of primary afferents within laminae I and II (substantia gelatinosa) of the spinal cord and in the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve.

Morphine is a phenanthrene opioid receptor agonist – its main effect is binding to and activating the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) in the central nervous system. Its intrinsic activity at the MOR is heavily dependent on the assay and tissue being tested; in some situations it is a full agonist while in others it can be a partial agonist or even antagonist. In clinical settings, morphine exerts its principal pharmacological effect on the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. Its primary actions of therapeutic value are analgesia and sedation. Activation of the MOR is associated with analgesia, sedation, euphoria, physical dependence, and respiratory depression. Morphine is also a κ-opioid receptor (KOR) and δ-opioid receptor (DOR) agonist. Activation of the KOR is associated with spinal analgesia, miosis (pinpoint pupils), and psychotomimetic effects. The DOR is thought to play a role in analgesia. Although morphine does not bind to the σ receptor, it has been shown that σ receptor agonists, such as (+)-pentazocine, inhibit morphine analgesia, and σ receptor antagonists enhance morphine analgesia, suggesting downstream involvement of the σ receptor in the actions of morphine.

The effects of morphine can be countered with opioid receptor antagonists such as naloxone and naltrexone; the development of tolerance to morphine may be inhibited by NMDA receptor antagonists such as ketamine or dextromethorphan. The rotation of morphine with chemically dissimilar opioids in the long-term treatment of pain will slow down the growth of tolerance in the longer run, particularly agents known to have significantly incomplete cross-tolerance with morphine such as levorphanol, ketobemidone, piritramide, and methadone and its derivatives; all of these drugs also have NMDA antagonist properties. It is believed that the strong opioid with the most incomplete cross-tolerance with morphine is either methadone or dextromoramide.

Gene expression

Studies have shown that morphine can alter the expression of a number of genes. A single injection of morphine has been shown to alter the expression of two major groups of genes, for proteins involved in mitochondrial respiration and for cytoskeleton-related proteins.

Effects on the immune system

Morphine has long been known to act on receptors expressed on cells of the central nervous system resulting in pain relief and analgesia. In the 1970s and '80s, evidence suggesting that opioid drug addicts show increased risk of infection (such as increased pneumonia, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS) led scientists to believe that morphine may also affect the immune system. This possibility increased interest in the effect of chronic morphine use on the immune system.

The first step of determining that morphine may affect the immune system was to establish that the opiate receptors known to be expressed on cells of the central nervous system are also expressed on cells of the immune system. One study successfully showed that dendritic cells, part of the innate immune system, display opiate receptors. Dendritic cells are responsible for producing cytokines, which are the tools for communication in the immune system. This same study showed that dendritic cells chronically treated with morphine during their differentiation produce more interleukin-12 (IL-12), a cytokine responsible for promoting the proliferation, growth, and differentiation of T-cells (another cell of the adaptive immune system) and less interleukin-10 (IL-10), a cytokine responsible for promoting a B-cell immune response (B cells produce antibodies to fight off infection).

This regulation of cytokines appear to occur via the p38 MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinase)-dependent pathway. Usually, the p38 within the dendritic cell expresses TLR 4 (toll-like receptor 4), which is activated through the ligand LPS (lipopolysaccharide). This causes the p38 MAPK to be phosphorylated. This phosphorylation activates the p38 MAPK to begin producing IL-10 and IL-12. When the dendritic cells are chronically exposed to morphine during their differentiation process then treated with LPS, the production of cytokines is different. Once treated with morphine, the p38 MAPK does not produce IL-10, instead favoring production of IL-12. The exact mechanism through which the production of one cytokine is increased in favor over another is not known. Most likely, the morphine causes increased phosphorylation of the p38 MAPK. Transcriptional level interactions between IL-10 and IL-12 may further increase the production of IL-12 once IL-10 is not being produced. This increased production of IL-12 causes increased T-cell immune response.

Further studies on the effects of morphine on the immune system have shown that morphine influences the production of neutrophils and other cytokines. Since cytokines are produced as part of the immediate immunological response (inflammation), it has been suggested that they may also influence pain. In this way, cytokines may be a logical target for analgesic development. Recently, one study has used an animal model (hind-paw incision) to observe the effects of morphine administration on the acute immunological response. Following hind-paw incision, pain thresholds and cytokine production were measured. Normally, cytokine production in and around the wounded area increases in order to fight infection and control healing (and, possibly, to control pain), but pre-incisional morphine administration (0.1 mg/kg to 10.0 mg/kg) reduced the number of cytokines found around the wound in a dose-dependent manner. The authors suggest that morphine administration in the acute post-injury period may reduce resistance to infection and may impair the healing of the wound.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption and metabolism

Morphine can be taken orally, sublingually, bucally, rectally, subcutaneously, intranasally, intravenously, intrathecally or epidurally and inhaled via a nebulizer. As a recreational drug, it is becoming more common to inhale ("Chasing the Dragon"), but, for medical purposes, intravenous (IV) injection is the most common method of administration. Morphine is subject to extensive first-pass metabolism (a large proportion is broken down in the liver), so, if taken orally, only 40% to 50% of the dose reaches the central nervous system. Resultant plasma levels after subcutaneous (SC), intramuscular (IM), and IV injection are all comparable. After IM or SC injections, morphine plasma levels peak in approximately 20 min, and, after oral administration, levels peak in approximately 30 min. Morphine is metabolised primarily in the liver and approximately 87% of a dose of morphine is excreted in the urine within 72 h of administration. Morphine is metabolized primarily into morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G) via glucuronidation by phase II metabolism enzyme UDP-glucuronosyl transferase-2B7 (UGT2B7). About 60% of morphine is converted to M3G, and 6% to 10% is converted to M6G. Not only does the metabolism occur in the liver but it may also take place in the brain and the kidneys. M3G does not undergo opioid receptor binding and has no analgesic effect. M6G binds to μ-receptors and is half as potent an analgesic as morphine in humans. Morphine may also be metabolized into small amounts of normorphine, codeine, and hydromorphone. Metabolism rate is determined by gender, age, diet, genetic makeup, disease state (if any), and use of other medications. The elimination half-life of morphine is approximately 120 min, though there may be slight differences between men and women. Morphine can be stored in fat, and, thus, can be detectable even after death. Morphine can cross the blood–brain barrier, but, because of poor lipid solubility, protein binding, rapid conjugation with glucuronic acid and ionization, it does not cross easily. Heroin, which is derived from morphine, crosses the blood–brain barrier more easily, making it more potent.

Extended-release

There are extended-release formulations of orally administered morphine whose effect last longer, which can be given once per day. Brand names for this formulation of morphine include Avinza, Kadian, MS Contin and Dolcontin. For constant pain, the relieving effect of extended-release morphine given once (for Kadian) or twice (for MS Contin) every 24 hours is roughly the same as multiple administrations of immediate release (or "regular") morphine. Extended-release morphine can be administered together with "rescue doses" of immediate-release morphine as needed in case of breakthrough pain, each generally consisting of 5% to 15% of the 24-hour extended-release dosage.

Detection in body fluids

Morphine and its major metabolites, morphine-3-glucuronide and morphine-6-glucuronide, can be detected in blood, plasma, hair, and urine using an immunoassay. Chromatography can be used to test for each of these substances individually. Some testing procedures hydrolyze metabolic products into morphine before the immunoassay, which must be considered when comparing morphine levels in separately published results. Morphine can also be isolated from whole blood samples by solid phase extraction (SPE) and detected using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Ingestion of codeine or food containing poppy seeds can cause false positives.

A 1999 review estimated that relatively low doses of heroin (which metabolizes immediately into morphine) are detectable by standard urine tests for 1–1.5 days after use. A 2009 review determined that, when the analyte is morphine and the limit of detection is 1 ng/ml, a 20 mg intravenous (IV) dose of morphine is detectable for 12–24 hours. A limit of detection of 0.6 ng/ml had similar results.

Natural occurrence

Morphine is the most abundant opiate found in opium, the dried latex extracted by shallowly scoring the unripe seedpods of the Papaver somniferum poppy. Morphine is generally 8–14% of the dry weight of opium, although specially bred cultivars reach 26% or produce little morphine at all (under 1%, perhaps down to 0.04%). The latter varieties, including the 'Przemko' and 'Norman' cultivars of the opium poppy, are used to produce two other alkaloids, thebaine and oripavine, which are used in the manufacture of semi-synthetic and synthetic opioids like oxycodone and etorphine and some other types of drugs. P. bracteatum does not contain morphine or codeine, or other narcotic phenanthrene-type, alkaloids. This species is rather a source of thebaine. Occurrence of morphine in other Papaverales and Papaveraceae, as well as in some species of hops and mulberry trees has not been confirmed. Morphine is produced most predominantly early in the life cycle of the plant. Past the optimum point for extraction, various processes in the plant produce codeine, thebaine, and in some cases negligible amounts of hydromorphone, dihydromorphine, dihydrocodeine, tetrahydro-thebaine, and hydrocodone (these compounds are rather synthesized from thebaine and oripavine).

In the brain of mammals, morphine is detectable in trace steady-state concentrations. The human body also produces endorphins, which are chemically related endogenous opioid peptides that function as neuropeptides and have similar effects to morphine.

Human biosynthesis

Morphine is an endogenous opioid in humans that can be synthesized by and released from various human cells, including white blood cells. CYP2D6, a cytochrome P450

isoenzyme, catalyzes the biosynthesis of morphine from codeine and

dopamine from tyramine along the biosynthetic pathway of morphine in

humans. The morphine biosynthetic pathway in humans occurs as follows:

L-tyrosine → para-tyramine or L-DOPA → dopamine → (S)-norlaudanosoline → (S)-reticuline → 1,2-dehydroretinulinium → (R)-reticuline → salutaridine → salutaridinol → thebaine → neopinone → codeinone → codeine → morphine

(S)-Norlaudanosoline (also known as tetrahydropapaveroline) can also be synthesized from 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL), a metabolite of L-DOPA and dopamine. Urinary concentrations of endogenous codeine and morphine have been found to significantly increase in individuals taking L-DOPA for the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

Biosynthesis in the opium poppy

Morphine is biosynthesized in the opium poppy from the tetrahydroisoquinoline reticuline. It is converted into salutaridine, thebaine, and oripavine. The enzymes involved in this process are the salutaridine synthase, salutaridine:NADPH 7-oxidoreductase and the codeinone reductase. Researchers are attempting to reproduce the biosynthetic pathway that produces morphine in genetically engineered yeast. In June 2015 the S-reticuline could be produced from sugar and R-reticuline could be converted to morphine, but the intermediate reaction could not be performed. In August 2015 the first complete synthesis of thebaine and hydrocodone in yeast were reported, but the process would need to be 100,000 times more productive to be suitable for commercial use.

Chemistry

Elements of the morphine structure have been used to create completely synthetic drugs such as the morphinan family (levorphanol, dextromethorphan and others) and other groups that have many members with morphine-like qualities. The modification of morphine and the aforementioned synthetics has also given rise to non-narcotic drugs with other uses such as emetics, stimulants, antitussives, anticholinergics, muscle relaxants, local anaesthetics, general anaesthetics, and others. As well, morphine-derived agonist–antagonist drugs have also been developed.

Structure description

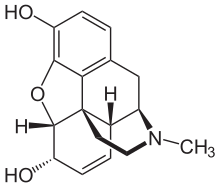

Morphine is a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid with two additional ring closures. As Jack DeRuiter of the Department of Drug Discovery and Development (formerly, Pharmacal Sciences), Harrison School of Pharmacy, Auburn University stated in his Fall 2000 course notes for that earlier department's "Principles of Drug Action 2" course, "Examination of the morphine molecule reveals the following structural features important to its pharmacological profile...

- A rigid pentacyclic structure consisting of a benzene ring (A), two partially unsaturated cyclohexane rings (B and C), a piperidine ring (D) and a tetrahydrofuran ring (E). Rings A, B and C are the phenanthrene ring system. This ring system has little conformational flexibility...

- Two hydroxyl functional groups: a C3-phenolic [hydroxyl group] (pKa 9.9) and a C6-allylic [hydroxyl group],

- An ether linkage between C4 and C5,

- Unsaturation between C7 and C8,

- A basic, [tertiary]-amine function at position 17, [and]

- [Five] centers of chirality (C5, C6, C9, C13 and C14) with morphine exhibiting a high degree of stereoselectivity of analgesic action."

Morphine and most of its derivatives do not exhibit optical isomerism, although some more distant relatives like the morphinan series (levorphanol, dextorphan and the racemic parent chemical racemorphan) do, and as noted above stereoselectivity in vivo is an important issue.

Uses and derivatives

Most of the licit morphine produced is used to make codeine by methylation. It is also a precursor for many drugs including heroin (3,6-diacetylmorphine), hydromorphone (dihydromorphinone), and oxymorphone (14-hydroxydihydromorphinone). Most semi-synthetic opioids, both of the morphine and codeine subgroups, are created by modifying one or more of the following:

- Halogenating or making other modifications at positions 1 or 2 on the morphine carbon skeleton.

- The methyl group that makes morphine into codeine can be removed or added back, or replaced with another functional group like ethyl and others to make codeine analogues of morphine-derived drugs and vice versa. Codeine analogues of morphine-based drugs often serve as prodrugs of the stronger drug, as in codeine and morphine, hydrocodone and hydromorphone, oxycodone and oxymorphone, nicocodeine and nicomorphine, dihydrocodeine and dihydromorphine, etc.

- Saturating, opening, or other changes to the bond between positions 7 and 8, as well as adding, removing, or modifying functional groups to these positions; saturating, reducing, eliminating, or otherwise modifying the 7–8 bond and attaching a functional group at 14 yields hydromorphinol; the oxidation of the hydroxyl group to a carbonyl and changing the 7–8 bond to single from double changes codeine into oxycodone.

- Attachment, removal or modification of functional groups to positions 3 or 6 (dihydrocodeine and related, hydrocodone, nicomorphine); in the case of moving the methyl functional group from position 3 to 6, codeine becomes heterocodeine, which is 72 times stronger, and therefore six times stronger than morphine

- Attachment of functional groups or other modification at position 14 (oxymorphone, oxycodone, naloxone)

- Modifications at positions 2, 4, 5 or 17, usually along with other changes to the molecule elsewhere on the morphine skeleton. Often this is done with drugs produced by catalytic reduction, hydrogenation, oxidation, or the like, producing strong derivatives of morphine and codeine.

Many morphine derivatives can also be manufactured using thebaine or codeine as a starting material.[citation needed] Replacement of the N-methyl group of morphine with an N-phenylethyl group results in a product that is 18 times more powerful than morphine in its opiate agonist potency. Combining this modification with the replacement of the 6-hydroxyl with a 6-methylene group produces a compound some 1,443 times more potent than morphine, stronger than the Bentley compounds such as etorphine (M99, the Immobilon tranquilliser dart) by some measures. Closely related to morphine are the opioids morphine-N-oxide (genomorphine), which is a pharmaceutical that is no longer in common use; and pseudomorphine, an alkaloid that exists in opium, form as degradation products of morphine.

As a result of the extensive study and use of this molecule, more than 250 morphine derivatives (also counting codeine and related drugs) have been developed since the last quarter of the 19th century. These drugs range from 25% the analgesic strength of codeine (or slightly more than 2% of the strength of morphine) to several thousand times the strength of morphine, to powerful opioid antagonists, including naloxone (Narcan), naltrexone (Trexan), diprenorphine (M5050, the reversing agent for the Immobilon dart) and nalorphine (Nalline). Some opioid agonist-antagonists, partial agonists, and inverse agonists are also derived from morphine. The receptor-activation profile of the semi-synthetic morphine derivatives varies widely and some, like apomorphine are devoid of narcotic effects.

Salts

Both morphine and its hydrated form are sparingly soluble in water. For this reason, pharmaceutical companies produce sulfate and hydrochloride salts of the drug, both of which are over 300 times more water-soluble than their parent molecule. Whereas the pH of a saturated morphine hydrate solution is 8.5, the salts are acidic. Since they derive from a strong acid but weak base, they are both at about pH = 5; as a consequence, the morphine salts are mixed with small amounts of NaOH to make them suitable for injection.

A number of salts of morphine are used, with the most common in current clinical use being the hydrochloride, sulfate, tartrate, and citrate; less commonly methobromide, hydrobromide, hydroiodide, lactate, chloride, and bitartrate and the others listed below. Morphine diacetate (heroin) is not a salt, but rather a further derivative, see above.

Morphine meconate is a major form of the alkaloid in the poppy, as is morphine pectinate, nitrate, sulfate, and some others. Like codeine, dihydrocodeine and other (especially older) opiates, morphine has been used as the salicylate salt by some suppliers and can be easily compounded, imparting the therapeutic advantage of both the opioid and the NSAID; multiple barbiturate salts of morphine were also used in the past, as was/is morphine valerate, the salt of the acid being the active principle of valerian. Calcium morphenate is the intermediate in various latex and poppy-straw methods of morphine production, more rarely sodium morphenate takes its place. Morphine ascorbate and other salts such as the tannate, citrate, and acetate, phosphate, valerate and others may be present in poppy tea depending on the method of preparation.

Production

In the opium poppy, the alkaloids are bound to meconic acid. The method is to extract from the crushed plant with diluted sulfuric acid, which is a stronger acid than meconic acid, but not so strong to react with alkaloid molecules. The extraction is performed in many steps (one amount of crushed plant is extracted at least six to ten times, so practically every alkaloid goes into the solution). From the solution obtained at the last extraction step, the alkaloids are precipitated by either ammonium hydroxide or sodium carbonate. The last step is purifying and separating morphine from other opium alkaloids. The somewhat similar Gregory process was developed in the United Kingdom during the Second World War, which begins with stewing the entire plant, in most cases save the roots and leaves, in plain or mildly acidified water, then proceeding through steps of concentration, extraction, and purification of alkaloids. Other methods of processing "poppy straw" (i.e., dried pods and stalks) use steam, one or more of several types of alcohol, or other organic solvents.

The poppy straw methods predominate in Continental Europe and the British Commonwealth, with the latex method in most common use in India. The latex method can involve either vertical or horizontal slicing of the unripe pods with a two-to five-bladed knife with a guard developed specifically for this purpose to the depth of a fraction of a millimetre and scoring of the pods can be done up to five times. An alternative latex method sometimes used in China in the past is to cut off the poppy heads, run a large needle through them, and collect the dried latex 24 to 48 hours later.

In India, opium harvested by licensed poppy farmers is dehydrated to uniform levels of hydration at government processing centers, and then sold to pharmaceutical companies that extract morphine from the opium. However, in Turkey and Tasmania, morphine is obtained by harvesting and processing the fully mature dry seed pods with attached stalks, called poppy straw. In Turkey, a water extraction process is used, while in Tasmania, a solvent extraction process is used.

Opium poppy contains at least 50 different alkaloids, but most of them are of very low concentration. Morphine is the principal alkaloid in raw opium and constitutes roughly 8–19% of opium by dry weight (depending on growing conditions). Some purpose-developed strains of poppy now produce opium that is up to 26% morphine by weight. A rough rule of thumb to determine the morphine content of pulverised dried poppy straw is to divide the percentage expected for the strain or crop via the latex method by eight or an empirically determined factor, which is often in the range of 5 to 15. The Norman strain of P. Somniferum, also developed in Tasmania, produces down to 0.04% morphine but with much higher amounts of thebaine and oripavine, which can be used to synthesise semi-synthetic opioids as well as other drugs like stimulants, emetics, opioid antagonists, anticholinergics, and smooth-muscle agents.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Hungary supplied nearly 60% of Europe's total medication-purpose morphine production. To this day, poppy farming is legal in Hungary, but poppy farms are limited by law to 2 acres (8,100 m2). It is also legal to sell dried poppy in flower shops for use in floral arrangements.

It was announced in 1973 that a team at the National Institutes of Health in the United States had developed a method for total synthesis of morphine, codeine, and thebaine using coal tar as a starting material. A shortage in codeine-hydrocodone class cough suppressants (all of which can be made from morphine in one or more steps, as well as from codeine or thebaine) was the initial reason for the research.

Most morphine produced for pharmaceutical use around the world is actually converted into codeine as the concentration of the latter in both raw opium and poppy straw is much lower than that of morphine; in most countries, the usage of codeine (both as end-product and precursor) is at least equal or greater than that of morphine on a weight basis.

Chemical synthesis

The first morphine total synthesis, devised by Marshall D. Gates, Jr. in 1952, remains a widely used example of total synthesis. Several other syntheses were reported, notably by the research groups of Rice, Evans, Fuchs, Parker, Overman, Mulzer-Trauner, White, Taber, Trost, Fukuyama, Guillou, and Stork. Because of the stereochemical complexity and consequent synthetic challenge presented by this polycyclic structure, Michael Freemantle has expressed the view that it is "highly unlikely" that a chemical synthesis will ever be cost-effective such that it could compete with the cost of producing morphine from the opium poppy.

Precursor to other opioids

Pharmaceutical

Morphine is a precursor in the manufacture in a number of opioids such as dihydromorphine, hydromorphone, hydrocodone, and oxycodone as well as codeine, which itself has a large family of semi-synthetic derivatives.

Illicit

Illicit morphine is produced, though rarely, from codeine found in over-the-counter cough and pain medicines. Another illicit source is morphine extracted from extended-release morphine products. Chemical reactions can then be used to convert morphine, dihydromorphine, and hydrocodone into heroin or other opioids [e.g., diacetyldihydromorphine (Paralaudin), and thebacon]. Other clandestine conversions—of morphine, into ketones of the hydromorphone class, or other derivatives like dihydromorphine (Paramorfan), desomorphine (Permonid), metopon, etc., and of codeine into hydrocodone (Dicodid), dihydrocodeine (Paracodin), etc. —require greater expertise, and types and quantities of chemicals and equipment that are more difficult to source, and so are more rarely used, illicitly (but cases have been recorded).

History

An opium-based elixir has been ascribed to alchemists of Byzantine times, but the specific formula was lost during the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul). Around 1522, Paracelsus made reference to an opium-based elixir that he called laudanum from the Latin word laudare, meaning "to praise" He described it as a potent painkiller, but recommended that it be used sparingly. The recipe given differs substantially from that of modern-day laundanum.

Morphine was discovered as the first active alkaloid extracted from the opium poppy plant in December 1804 in Paderborn by German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner. In 1817, Sertürner reported experiments in which he administered morphine to himself, three young boys, three dogs, and a mouse; all four people almost died. Sertürner originally named the substance morphium after the Greek god of dreams, Morpheus, as it has a tendency to cause sleep. Sertürner's morphium was six times stronger than opium. He hypothesized that, because lower doses of the drug were needed, it would be less addictive. However Sertürner became addicted to the drug, warning that "I consider it my duty to attract attention to the terrible effects of this new substance I called morphium in order that calamity may be averted."

The drug was first marketed to the general public by Sertürner and Company in 1817 as a pain medication, and also as a treatment for opium and alcohol addiction. It was first used as a poison in 1822 when Dr. Edme Castaing of France was convicted of murdering a patient. Commercial production began in Darmstadt, Germany, in 1827 by the pharmacy that became the pharmaceutical company Merck, with morphine sales being a large part of their early growth. In the 1850s, Alexander Wood reported that he had injected morphine into his wife Rebecca as an experiment; the myth goes that this killed her because of respiratory depression, but she outlived her husband by ten years.

Later it was found that morphine was more addictive than either alcohol or opium, and its extensive use during the American Civil War allegedly resulted in over 400,000 sufferers from the "soldier's disease" of morphine addiction. This idea has been a subject of controversy, as there have been suggestions that such a disease was in fact a fabrication; the first documented use of the phrase "soldier's disease" was in 1915.

Diacetylmorphine (better known as heroin) was synthesized from morphine in 1874 and brought to market by Bayer in 1898. Heroin is approximately 1.5 to 2 times more potent than morphine weight for weight. Due to the lipid solubility of diacetylmorphine, it can cross the blood–brain barrier faster than morphine, subsequently increasing the reinforcing component of addiction. Using a variety of subjective and objective measures, one study estimated the relative potency of heroin to morphine administered intravenously to post-addicts to be 1.80–2.66 mg of morphine sulfate to 1 mg of diamorphine hydrochloride (heroin).

Morphine became a controlled substance in the US under the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, and possession without a prescription in the US is a criminal offense. Morphine was the most commonly abused narcotic analgesic in the world until heroin was synthesized and came into use. In general, until the synthesis of dihydromorphine (ca. 1900), the dihydromorphinone class of opioids (1920s), and oxycodone (1916) and similar drugs, there were no other drugs in the same efficacy range as opium, morphine, and heroin, with synthetics still several years away (pethidine was invented in Germany in 1937) and opioid agonists among the semi-synthetics were analogues and derivatives of codeine such as dihydrocodeine (Paracodin), ethylmorphine (Dionine), and benzylmorphine (Peronine). Even today, morphine is the most sought after prescription narcotic by heroin addicts when heroin is scarce, all other things being equal; local conditions and user preference may cause hydromorphone, oxymorphone, high-dose oxycodone, or methadone as well as dextromoramide in specific instances such as 1970s Australia, to top that particular list. The stop-gap drugs used by the largest absolute number of heroin addicts is probably codeine, with significant use also of dihydrocodeine, poppy straw derivatives like poppy pod and poppy seed tea, propoxyphene, and tramadol.

The structural formula of morphine was determined by 1925 by Robert Robinson. At least three methods of total synthesis of morphine from starting materials such as coal tar and petroleum distillates have been patented, the first of which was announced in 1952, by Dr. Marshall D. Gates, Jr. at the University of Rochester. Still, the vast majority of morphine is derived from the opium poppy by either the traditional method of gathering latex from the scored, unripe pods of the poppy, or processes using poppy straw, the dried pods and stems of the plant, the most widespread of which was invented in Hungary in 1925 and announced in 1930 by Hungarian pharmacologist János Kabay.

In 2003, there was discovery of endogenous morphine occurring naturally in the human body. Thirty years of speculation were made on this subject because there was a receptor that, it appeared, reacted only to morphine: the μ3-opioid receptor in human tissue. Human cells that form in reaction to cancerous neuroblastoma cells have been found to contain trace amounts of endogenous morphine.

Society and culture

Legal status

- In Australia, morphine is classified as a Schedule 8 drug under the variously titled State and Territory Poisons Acts.

- In Canada, morphine is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

- In France, morphine is in the strictest schedule of controlled substances, based upon the December 1970 French controlled substances law.

- In Germany, morphine is a verkehrsfähiges und verschreibungsfähiges Betäubungsmittel listed under Anlage III (the equivalent of CSA Schedule II) of the Betäubungsmittelgesetz.

- In Switzerland, morphine is similarly scheduled to Germany's legal classification of the drug.

- In Japan, morphine is classified as a narcotic under the Narcotics and Psychotropics Control Act (麻薬及び向精神薬取締法, mayaku oyobi kōseishinyaku torishimarihō).

- In the Netherlands, morphine is classified as a List 1 drug under the Opium Law.

- In the United Kingdom, morphine is listed as a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and a Schedule 2 Controlled Drug under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001.

- In the United States, morphine is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act under main Administrative Controlled Substances Code Number 9300. Morphine pharmaceuticals are subject to annual manufacturing quotas; in 2017 these quotas were 35.0 tonnes of production for sale, and 27.3 tonnes of production as an intermediate, or chemical precursor, for conversion into other drugs. Morphine produced for use in extremely dilute formulations is excluded from the manufacturing quota.

- Internationally (UN), morphine is a Schedule I drug under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

Non-medical use

The euphoria, comprehensive alleviation of distress and therefore all aspects of suffering, promotion of sociability and empathy, "body high", and anxiolysis provided by narcotic drugs including the opioids can cause the use of high doses in the absence of pain for a protracted period, which can impart a morbid craving for the drug in the user. Being the prototype of the entire opioid class of drugs means that morphine has properties that may lend it to misuse. Morphine addiction is the model upon which the current perception of addiction is based.

Animal and human studies and clinical experience back up the contention that morphine is one of the most euphoric drugs known, and via all but the IV route heroin and morphine cannot be distinguished according to studies because heroin is a prodrug for the delivery of systemic morphine. Chemical changes to the morphine molecule yield other euphorigenics such as dihydromorphine, hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Hydal), and oxymorphone (Numorphan, Opana), as well as the latter three's methylated equivalents dihydrocodeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone, respectively; in addition to heroin, there are dipropanoylmorphine, diacetyldihydromorphine, and other members of the 3,6 morphine diester category like nicomorphine and other similar semi-synthetic opiates like desomorphine, hydromorphinol, etc. used clinically in many countries of the world but in many cases also produced illicitly in rare instances.

In general, non-medical use of morphine entails taking more than prescribed or outside of medical supervision, injecting oral formulations, mixing it with unapproved potentiators such as alcohol, cocaine, and the like, or defeating the extended-release mechanism by chewing the tablets or turning into a powder for snorting or preparing injectables. The latter method can be as time-consuming and involved as traditional methods of smoking opium. This and the fact that the liver destroys a large percentage of the drug on the first pass impacts the demand side of the equation for clandestine re-sellers, as many customers are not needle users and may have been disappointed with ingesting the drug orally. As morphine is generally as hard or harder to divert than oxycodone in a lot of cases, morphine in any form is uncommon on the street, although ampoules and phials of morphine injection, pure pharmaceutical morphine powder, and soluble multi-purpose tablets are very popular where available.

Morphine is also available in a paste that is used in the production of heroin, which can be smoked by itself or turned to a soluble salt and injected; the same goes for the penultimate products of the Kompot (Polish Heroin) and black tar processes. Poppy straw as well as opium can yield morphine of purity levels ranging from poppy tea to near-pharmaceutical-grade morphine by itself or with all of the more than 50 other alkaloids. It also is the active narcotic ingredient in opium and all of its forms, derivatives, and analogues as well as forming from breakdown of heroin and otherwise present in many batches of illicit heroin as the result of incomplete acetylation.

Names

Morphine is marketed under many different brand names in various parts of the world. It was formerly called Morphia in British English.

Informal names for morphine include: Cube Juice, Dope, Dreamer, Emsel, First Line, God's Drug, Hard Stuff, Hocus, Hows, Lydia, Lydic, M, Miss Emma, Mister Blue, Monkey, Morf, Morph, Morphide, Morphie, Morpho, Mother, MS, Ms. Emma, Mud, New Jack Swing (if mixed with heroin), Sister, Tab, Unkie, Unkie White, and Stuff.

MS Contin tablets are known as misties, and the 100 mg extended-release tablets as greys and blockbusters. The "speedball" can use morphine as the opioid component, which is combined with cocaine, amphetamines, methylphenidate, or similar drugs. "Blue Velvet" is a combination of morphine with the antihistamine tripelennamine (Pyrabenzamine, PBZ, Pelamine) taken by injection, or less commonly the mixture when swallowed or used as a retention enema; the name is also known to refer to a combination of tripelennamine and dihydrocodeine or codeine tablets or syrups taken by mouth. "Morphia" is an older official term for morphine also used as a slang term. "Driving Miss Emma" is intravenous administration of morphine. Multi-purpose tablets (readily soluble hypodermic tablets that can also be swallowed or dissolved under the tongue or betwixt the cheek and jaw) are known, as are some brands of hydromorphone, as Shake & Bake or Shake & Shoot.

Morphine can be smoked, especially diacetylmorphine (heroin), the most common method being the "Chasing The Dragon" method. To perform a relatively crude acetylation to turn the morphine into heroin and related drugs immediately prior to use is known as AAing (for Acetic Anhydride) or home-bake, and the output of the procedure also known as home-bake or, Blue Heroin (not to be confused with Blue Magic heroin, or the linctus known as Blue Morphine or Blue Morphone, or the Blue Velvet mixture described above).

Access in developing countries

Although morphine is cheap, people in poorer countries often do not have access to it. According to a 2005 estimate by the International Narcotics Control Board, six countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States) consume 79% of the world's morphine. The less affluent countries, accounting for 80% of the world's population, consumed only about 6% of the global morphine supply. Some countries import virtually no morphine, and in others the drug is rarely available even for relieving severe pain while dying.

Experts in pain management attribute the under-distribution of morphine to an unwarranted fear of the drug's potential for addiction and abuse. While morphine is clearly addictive, Western doctors believe it is worthwhile to use the drug and then wean the patient off when the treatment is over.