The history of the scientific discovery of climate change began in the early 19th century when ice ages and other natural changes in paleoclimate were first suspected and the natural greenhouse effect was first identified. In the late 19th century, scientists first argued that human emissions of greenhouse gases could change the climate. Many other theories of climate change were advanced, involving forces from volcanism to solar variation. In the 1960s, the evidence for the warming effect of carbon dioxide gas became increasingly convincing. Some scientists also pointed out that human activities that generated atmospheric aerosols (e.g., "pollution") could have cooling effects as well.

During the 1970s, scientific opinion increasingly favored the warming viewpoint. By the 1990s, as a result of improving fidelity of computer models and observational work confirming the Milankovitch theory of the ice ages, a consensus position formed: greenhouse gases were deeply involved in most climate changes and human-caused emissions were bringing discernible global warming. Since the 1990s, scientific research on climate change has included multiple disciplines and has expanded. Research has expanded our understanding of causal relations, links with historic data and ability to model climate change numerically. Research during this period has been summarized in the Assessment Reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Climate change, broadly interpreted, is a significant and lasting change in the statistical distribution of weather patterns over periods ranging from decades to millions of years. It may be a change in average weather conditions, or in the distribution of weather around the average conditions (such as more or fewer extreme weather events). Climate change is caused by factors that include oceanic processes (such as oceanic circulation), biotic processes (e.g., plants), variations in solar radiation received by Earth, plate tectonics and volcanic eruptions, and human-induced alterations of the natural world. The latter effect is currently causing global warming, and "climate change" is often used to describe human-specific impacts.

Regional changes, antiquity through 19th century

From ancient times, people suspected that the climate of a region could change over the course of centuries. For example, Theophrastus, a pupil of Aristotle, told how the draining of marshes had made a particular locality more susceptible to freezing, and speculated that lands became warmer when the clearing of forests exposed them to sunlight. Renaissance and later scholars saw that deforestation, irrigation, and grazing had altered the lands around the Mediterranean since ancient times; they thought it plausible that these human interventions had affected the local weather. Vitruvius, in the first century BC, wrote about climate in relation to housing architecture and how to choose locations for cities.

The 18th and 19th-century conversion of Eastern North America from forest to croplands brought obvious change within a human lifetime. From the early 19th century, many believed the transformation was altering the region's climate—probably for the better. When farmers in America, dubbed "sodbusters", took over the Great Plains, they held that "rain follows the plow." Other experts disagreed, and some argued that deforestation caused rapid rainwater run-off and flooding, and could even result in reduced rainfall. European academics, convinced of the superiority of their own civilization, said that the Orientals of the Ancient Near East had heedlessly converted their once lush lands into impoverished deserts.

Meanwhile, national weather agencies had begun to compile masses of reliable observations of temperature, rainfall, and the like. When these figures were analyzed, they showed many rises and dips, but no steady long-term change. By the end of the 19th century, scientific opinion had turned decisively against any belief in a human influence on climate. And whatever the regional effects, few imagined that humans could affect the climate of the planet as a whole.

Paleo-climate change and theories of its causes, 19th century

From the mid-17th century, naturalists attempted to reconcile mechanical philosophy with theology, initially within a Biblical timescale. By the late 18th century, there was increasing acceptance of prehistoric epochs. Geologists found evidence of a succession of geological ages with changes in climate. There were various competing theories about these changes; Buffon proposed that the Earth had begun as an incandescent globe and was very gradually cooling. James Hutton, whose ideas of cyclic change over huge periods of time were later dubbed uniformitarianism, was among those who found signs of past glacial activity in places too warm for glaciers in modern times.

In 1815 Jean-Pierre Perraudin described for the first time how glaciers might be responsible for the giant boulders seen in alpine valleys. As he hiked in the Val de Bagnes, he noticed giant granite rocks that were scattered around the narrow valley. He knew that it would take an exceptional force to move such large rocks. He also noticed how glaciers left stripes on the land and concluded that it was the ice that had carried the boulders down into the valleys.

His idea was initially met with disbelief. Jean de Charpentier wrote, "I found his hypothesis so extraordinary and even so extravagant that I considered it as not worth examining or even considering." Despite Charpentier's initial rejection, Perraudin eventually convinced Ignaz Venetz that it might be worth studying. Venetz convinced Charpentier, who in turn convinced the influential scientist Louis Agassiz that the glacial theory had merit.

Agassiz developed a theory of what he termed "Ice Age"—when glaciers covered Europe and much of North America. In 1837 Agassiz was the first to scientifically propose that the Earth had been subject to a past ice age. William Buckland had been a leading proponent in Britain of flood geology, later dubbed catastrophism, which accounted for erratic boulders and other "diluvium" as relics of the Biblical flood. This was strongly opposed by Charles Lyell's version of Hutton's uniformitarianism and was gradually abandoned by Buckland and other catastrophist geologists. A field trip to the Alps with Agassiz in October 1838 convinced Buckland that features in Britain had been caused by glaciation, and both he and Lyell strongly supported the ice age theory which became widely accepted by the 1870s.

Before the concept of ice ages was proposed, Joseph Fourier in 1824 reasoned on the basis of physics that Earth's atmosphere kept the planet warmer than would be the case in a vacuum. Fourier recognized that the atmosphere transmitted visible light waves efficiently to the earth's surface. The earth then absorbed visible light and emitted infrared radiation in response, but the atmosphere did not transmit infrared efficiently, which therefore increased surface temperatures. He also suspected that human activities could influence climate, although he focused primarily on land-use changes. In an 1827 paper, Fourier stated, "The establishment and progress of human societies, the action of natural forces, can notably change, and in vast regions, the state of the surface, the distribution of water and the great movements of the air. Such effects are able to make to vary, in the course of many centuries, the average degree of heat; because the analytic expressions contain coefficients relating to the state of the surface and which greatly influence the temperature." Fourier's work build on previous discoveries: in 1681 Edme Mariotte noted that glass, though transparent to sunlight, obstructs radiant heat. Around 1774 Horace Bénédict de Saussure showed that non-luminous warm objects emit infrared heat, and used a glass-topped insulated box to trap and measure heat from sunlight.

The physicist Claude Pouillet proposed in 1838 that water vapor and carbon dioxide might trap infrared and warm the atmosphere, but there was still no experimental evidence of these gases absorbing heat from thermal radiation.

The warming effect of electromagnetic radiation on different gases was examined in 1856 by Eunice Newton Foote, who described her experiments using glass tubes exposed to sunlight. The warming effect of the sun was greater for compressed air than for an evacuated tube and greater for moist air than dry air. "Thirdly, the highest effect of the sun's rays I have found to be in carbonic acid gas." (carbon dioxide) She continued: "An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if, as some suppose, at one period of its history, the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action, as well as from an increased weight, must have necessarily resulted." Her work was presented by Prof. Joseph Henry at the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in August 1856 and described as a brief note written by then journalist David Ames Wells; her paper was published later that year in the American Journal of Science and Arts.

John Tyndall took Fourier's work one step further in 1859 when he investigated the absorption of infrared radiation in different gases. He found that water vapor, hydrocarbons like methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2) strongly block the radiation.

Some scientists suggested that ice ages and other great climate changes were due to changes in the amount of gases emitted in volcanism. But that was only one of many possible causes. Another obvious possibility was solar variation. Shifts in ocean currents also might explain many climate changes. For changes over millions of years, the raising and lowering of mountain ranges would change patterns of both winds and ocean currents. Or perhaps the climate of a continent had not changed at all, but it had grown warmer or cooler because of polar wander (the North Pole shifting to where the Equator had been or the like). There were dozens of theories.

For example, in the mid-19th century, James Croll published calculations of how the gravitational pulls of the Sun, Moon, and planets subtly affect the Earth's motion and orientation. The inclination of the Earth's axis and the shape of its orbit around the Sun oscillate gently in cycles lasting tens of thousands of years. During some periods the Northern Hemisphere would get slightly less sunlight during the winter than it would get during other centuries. Snow would accumulate, reflecting sunlight and leading to a self-sustaining ice age. Most scientists, however, found Croll's ideas—and every other theory of climate change—unconvincing.

First calculations of greenhouse effect, 1896

By the late 1890s, Samuel Pierpoint Langley along with Frank W. Very

had attempted to determine the surface temperature of the Moon by

measuring infrared radiation leaving the Moon and reaching the Earth. The angle of the Moon in the sky when a scientist took a measurement determined how much CO

2

and water vapor the Moon's radiation had to pass through to reach the

Earth's surface, resulting in weaker measurements when the Moon was low

in the sky. This result was unsurprising given that scientists had

known about infrared radiation absorption for decades.

In 1896 Svante Arrhenius

used Langley's observations of increased infrared absorption where Moon

rays pass through the atmosphere at a low angle, encountering more carbon dioxide (CO

2), to estimate an atmospheric cooling effect from a future decrease of CO

2. He realized that the cooler atmosphere would hold less water vapor (another greenhouse gas)

and calculated the additional cooling effect. He also realized the

cooling would increase snow and ice cover at high latitudes, making the

planet reflect more sunlight and thus further cool down, as James Croll had hypothesized. Overall Arrhenius calculated that cutting CO

2 in half would suffice to produce an ice age. He further calculated that a doubling of atmospheric CO

2 would give a total warming of 5–6 degrees Celsius.

Further, Arrhenius' colleague Arvid Högbom, who was quoted in length in Arrhenius' 1896 study On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Earth had been attempting to quantify natural sources of emissions of CO

2 for purposes of understanding the global carbon cycle.

Högbom found that estimated carbon production from industrial sources

in the 1890s (mainly coal burning) was comparable with the natural

sources.

Arrhenius saw that this human emission of carbon would eventually lead

to warming. However, because of the relatively low rate of CO

2

production in 1896, Arrhenius thought the warming would take thousands

of years, and he expected it would be beneficial to humanity.

In 1899 Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin developed at length the idea that changes in climate could result from changes in the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Chamberlin wrote in his 1899 book, An Attempt to Frame a Working Hypothesis of the Cause of Glacial Periods on an Atmospheric Basis:

Previous advocacy of an atmospheric hypothesis, — The general doctrine that the glacial periods may have been due to a change in the atmospheric content of carbon dioxide is not new. It was urged by Tyndall a half century ago and has been urged by others since. Recently it has been very effectively advocated by Dr. Arrhenius, who has taken a great step in advance of his predecessors in reducing his conclusions to definite quantitative terms deduced from observational data. [..] The functions of carbon dioxide. — By the investigations of Tyndall, Lecher and Pretner, Keller, Roentgen, and Arrhenius, it has been shown that the carbon dioxide and water vapor of the atmosphere have remarkable power of absorbing and temporarily retaining heat rays, while the oxygen, nitrogen, and argon of the atmosphere possess this power in a feeble degree only. It follows that the effect of the carbon dioxide and water vapor is to blanket the earth with a thermally absorbent envelope. [..] The general results assignable to a greatly increased or a greatly reduced quantity of atmospheric carbon dioxide and water may be summarized as follows:

- a. An increase, by causing a larger absorption of the sun's radiant energy, raises the average temperature, while a reduction lowers it. The estimate of Dr. Arrhenius, based upon an elaborate mathematical discussion of the observations of Professor Langley, is that an increase of the carbon dioxide to the amount of two or three times the present content would elevate the average temperature 8° or 9° C. and would bring on a mild climate analogous to that which prevailed in the Middle Tertiary age. On the other hand, a reduction of the quantity of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to an amount ranging from 55 to 62 per cent, of the present content, would reduce the average temperature 4 or 5 C, which would bring on a glaciation comparable to that of the Pleistocene period.

- b. A second effect of increase and decrease in the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide is the equalization, on the one hand, of surface temperatures, or their differentiation on the other. The temperature of the surface of the earth varies with latitude, altitude, the distribution of land and water, day and night, the seasons, and some other elements that may here be neglected. It is postulated that an increase in the thermal absorption of the atmosphere equalizes the temperature, and tends to eliminate the variations attendant on these contingencies. Conversely, a reduction of thermal atmospheric absorption tends to intensify all of these variations. A secondary effect of intensification of differences of temperature is an increase of atmospheric movements in the effort to restore equilibrium. Increased atmospheric movements, which are necessarily convectional, carry the warmer air to the surface of the atmosphere, and facilitate the discharge of the heat and thus intensify the primary effect. [..]

In the case of the outgoing rays, which are absorbed in much larger proportions than the incoming rays because they are more largely long-wave rays, the tables of Arrhenius show that the absorption is augmented by increase of carbonic acid in greater proportions in high latitudes than in low; for example, the increase of temperature for three times the present content of carbonic acid is 21.5 per cent, greater between 60° and 70° N. latitude than at the equator.

It now becomes necessary to assign agencies capable of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at a rate sufficiently above the normal rate of supply, at certain times, to produce glaciation; and on the other hand, capable of restoring it to the atmosphere at certain other times in sufficient amounts to produce mild climates.

When the temperature is rising after a glacial episode, dissociation is promoted, and the ocean gives forth its carbon dioxide at an increased rate, and thereby assists in accelerating the amelioration of climate.

A study of the life of the geological periods seems to indicate that there were very notable fluctuations in the total mass of living matter. To be sure there was a reciprocal relation between the life of the land and that of the sea, so that when the latter was extended upon the continental platforms and greatly augmented, the former was contracted, but notwithstanding this it seems clear that the sum of life activity fluctuated notably during the ages. It is believed that on the whole it was greatest at the periods of sea extension and mild climates, and least at the times of disruption and climatic intensification. This factor then acted antithetically to the carbonic acid freeing previously noted, and, so far as it went, tended to offset its effects.

In periods of sea extension and of land reduction (base-level periods in particular), the habitat of shallow water lime-secreting life is concurrently extended, giving to the agencies that set carbon dioxide free accelerated activity, which is further aided by the consequent rising temperature which reduces the absorptive power of the ocean and increases dissociation. At the same time, the area of the land being diminished, a low consumption of carbon dioxide both in original decomposition of the silicates and in the solution of the limestones and dolomites obtains.

Thus the reciprocating agencies again conjoin, but now to increase the carbon dioxide of the air. These are the great and essential factors. They are modified by several subordinate agencies already mentioned, but the quantitative effect of these is thought to be quite insufficient to prevent very notable fluctuations in the atmospheric constitution.

As a result, it is postulated that geological history has been accentuated by an alternation of climatic episodes embracing, on the one hand, periods of mild, equable, moist climate nearly uniform for the whole globe; and on the other, periods when there were extremes of aridity and precipitation, and of heat and cold; these last denoted by deposits of salt and gypsum, of subaerial conglomerates, of red sandstones and shales, of arkose deposits, and occasionally by glaciation in low latitudes.

The term "greenhouse effect" for this warming was introduced by John Henry Poynting in 1909, in a commentary discussing the effect of the atmosphere on the temperature of the Earth and Mars.

Paleoclimates and sunspots, early 1900s to 1950s

Arrhenius's

calculations were disputed and subsumed into a larger debate over

whether atmospheric changes had caused the ice ages. Experimental

attempts to measure infrared absorption in the laboratory seemed to show

little differences resulted from increasing CO

2 levels, and also found significant overlap between absorption by CO

2

and absorption by water vapor, all of which suggested that increasing

carbon dioxide emissions would have little climatic effect. These early

experiments were later found to be insufficiently accurate, given the

instrumentation of the time. Many scientists also thought that the

oceans would quickly absorb any excess carbon dioxide.

Other theories of the causes of climate change fared no better. The principal advances were in observational paleoclimatology, as scientists in various fields of geology worked out methods to reveal ancient climates. Wilmot H. Bradley found that annual varves of clay laid down in lake beds showed climate cycles. Andrew Ellicott Douglass saw strong indications of climate change in tree rings. Noting that the rings were thinner in dry years, he reported climate effects from solar variations, particularly in connection with the 17th-century dearth of sunspots (the Maunder Minimum) noticed previously by William Herschel and others. Other scientists, however, found good reason to doubt that tree rings could reveal anything beyond random regional variations. The value of tree rings for climate study was not solidly established until the 1960s.

Through the 1930s the most persistent advocate of a solar-climate connection was astrophysicist Charles Greeley Abbot. By the early 1920s, he had concluded that the solar "constant" was misnamed: his observations showed large variations, which he connected with sunspots passing across the face of the Sun. He and a few others pursued the topic into the 1960s, convinced that sunspot variations were a main cause of climate change. Other scientists were skeptical. Nevertheless, attempts to connect the solar cycle with climate cycles were popular in the 1920s and 1930s. Respected scientists announced correlations that they insisted were reliable enough to make predictions. Sooner or later, every prediction failed, and the subject fell into disrepute.

Meanwhile, Milutin Milankovitch, building on James Croll's theory, improved the tedious calculations of the varying distances and angles of the Sun's radiation as the Sun and Moon gradually perturbed the Earth's orbit. Some observations of varves (layers seen in the mud covering the bottom of lakes) matched the prediction of a Milankovitch cycle lasting about 21,000 years. However, most geologists dismissed the astronomical theory. For they could not fit Milankovitch's timing to the accepted sequence, which had only four ice ages, all of them much longer than 21,000 years.

In 1938 Guy Stewart Callendar attempted to revive Arrhenius's greenhouse-effect theory. Callendar presented evidence that both temperature and the CO

2 level in the atmosphere had been rising over the past half-century, and he argued that newer spectroscopic

measurements showed that the gas was effective in absorbing infrared in

the atmosphere. Nevertheless, most scientific opinion continued to

dispute or ignore the theory.

Increasing concern, 1950s–1960s

Better spectrography in the 1950s showed that CO

2

and water vapor absorption lines did not overlap completely.

Climatologists also realized that little water vapor was present in the

upper atmosphere. Both developments showed that the CO

2 greenhouse effect would not be overwhelmed by water vapor.

In 1955 Hans Suess's carbon-14 isotope analysis showed that CO

2 released from fossil fuels was not immediately absorbed by the ocean. In 1957, better understanding of ocean chemistry led Roger Revelle

to a realization that the ocean surface layer had limited ability to

absorb carbon dioxide, also predicting the rise in levels of CO

2 and later being proven by Charles David Keeling.

By the late 1950s, more scientists were arguing that carbon dioxide

emissions could be a problem, with some projecting in 1959 that CO

2 would rise 25% by the year 2000, with potentially "radical" effects on climate.

In the centennial of the American oil industry in 1959, organized by

the American Petroleum Institute and the Columbia Graduate School of

Business, Edward Teller

said "It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a

10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the

icecap and submerge New York. [....] At present the carbon dioxide in

the atmosphere has risen by 2 per cent over normal. By 1970, it will be

perhaps 4 per cent, by 1980, 8 per cent, by 1990, 16 per cent if we keep

on with our exponential rise in the use of purely conventional fuels.". In 1960 Charles David Keeling demonstrated that the level of CO

2 in the atmosphere was in fact rising. Concern mounted year by year along with the rise of the "Keeling Curve" of atmospheric CO

2.

Another clue to the nature of climate change came in the mid-1960s from analysis of deep-sea cores by Cesare Emiliani and analysis of ancient corals by Wallace Broecker and collaborators. Rather than four long ice ages, they found a large number of shorter ones in a regular sequence. It appeared that the timing of ice ages was set by the small orbital shifts of the Milankovitch cycles. While the matter remained controversial, some began to suggest that the climate system is sensitive to small changes and can readily be flipped from a stable state into a different one.

Scientists meanwhile began using computers to develop more sophisticated versions of Arrhenius's calculations. In 1967, taking advantage of the ability of digital computers to integrate absorption curves numerically, Syukuro Manabe and Richard Wetherald made the first detailed calculation of the greenhouse effect incorporating convection (the "Manabe-Wetherald one-dimensional radiative-convective model"). They found that, in the absence of unknown feedbacks such as changes in clouds, a doubling of carbon dioxide from the current level would result in approximately 2 °C increase in global temperature.

By the 1960s, aerosol pollution ("smog") had become a serious local problem in many cities, and some scientists began to consider whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution could affect global temperatures. Scientists were unsure whether the cooling effect of particulate pollution or warming effect of greenhouse gas emissions would predominate, but regardless, began to suspect that human emissions could be disruptive to climate in the 21st century if not sooner. In his 1968 book The Population Bomb, Paul R. Ehrlich wrote, "the greenhouse effect is being enhanced now by the greatly increased level of carbon dioxide... [this] is being countered by low-level clouds generated by contrails, dust, and other contaminants... At the moment we cannot predict what the overall climatic results will be of our using the atmosphere as a garbage dump."

Efforts to establish a global temperature record that began in 1938 culminated in 1963, when J. Murray Mitchell presented one of the first up-to-date temperature reconstructions. His study involved data from over 200 weather stations, collected by the World Weather Records, which was used to calculate latitudinal average temperature. In his presentation, Murray showed that, beginning in 1880, global temperatures increased steadily until 1940. After that, a multi-decade cooling trend emerged. Murray’s work contributed to the overall acceptance of a possible global cooling trend.

In 1965, the landmark report, "Restoring the Quality of Our Environment" by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee warned of the harmful effects of fossil fuel emissions:

The part that remains in the atmosphere may have a significant effect on climate; carbon dioxide is nearly transparent to visible light, but it is a strong absorber and back radiator of infrared radiation, particularly in the wave lengths from 12 to 18 microns; consequently, an increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide could act, much like the glass in a greenhouse, to raise the temperature of the lower air.

The committee used the recently available global temperature reconstructions and carbon dioxide data from Charles David Keeling and colleagues to reach their conclusions. They declared the rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide levels to be the direct result of fossil fuel burning. The committee concluded that human activities were sufficiently large to have significant, global impact—beyond the area the activities take place. “Man is unwittingly conducting a vast geophysical experiment,” the committee wrote.

Nobel Prize winner Glenn T. Seaborg, Chairperson of the United States Atomic Energy Commission warned of the climate crisis in 1966: "At the rate we are currently adding carbon dioxide to our atmosphere (six billion tons a year), within the next few decades the heat balance of the atmosphere could be altered enough to produce marked changes in the climate--changes which we might have no means of controlling even if by that time we have made great advances in our programs of weather modification."

A 1968 study by the Stanford Research Institute for the American Petroleum Institute noted:

If the earth's temperature increases significantly, a number of events might be expected to occur, including the melting of the Antarctic ice cap, a rise in sea levels, warming of the oceans, and an increase in photosynthesis. [..] Revelle makes the point that man is now engaged in a vast geophysical experiment with his environment, the earth. Significant temperature changes are almost certain to occur by the year 2000 and these could bring about climatic changes.

In 1969, NATO was the first candidate to deal with climate change on an international level. It was planned then to establish a hub of research and initiatives of the organization in the civil area, dealing with environmental topics as acid rain and the greenhouse effect. The suggestion of US President Richard Nixon was not very successful with the administration of German Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger. But the topics and the preparation work done on the NATO proposal by the German authorities gained international momentum, (see e.g. the Stockholm United Nations Conference on the Human Environment 1970) as the government of Willy Brandt started to apply them on the civil sphere instead.

Also in 1969, Mikhail Budyko published a theory on the ice–albedo feedback, a foundational element of what is today known as Arctic amplification. The same year a similar model was published by William D. Sellers. Both studies attracted significant attention, since they hinted at the possibility for a runaway positive feedback within the global climate system.

Scientists increasingly predict warming, 1970s

In the early 1970s, evidence that aerosols were increasing worldwide and that the global temperature series showed cooling encouraged Reid Bryson and some others to warn of the possibility of severe cooling. The questions and concerns put forth by Bryson and others launched a new wave of research into the factors of such global cooling. Meanwhile, the new evidence that the timing of ice ages was set by predictable orbital cycles suggested that the climate would gradually cool, over thousands of years. Several scientific panels from this time period concluded that more research was needed to determine whether warming or cooling was likely, indicating that the trend in the scientific literature had not yet become a consensus. For the century ahead, however, a survey of the scientific literature from 1965 to 1979 found 7 articles predicting cooling and 44 predicting warming (many other articles on climate made no prediction); the warming articles were cited much more often in subsequent scientific literature. Research into warming and greenhouse gases held the greater emphasis, with nearly 6 times more studies predicting warming than predicting cooling, suggesting concern among scientists was largely over warming as they turned their attention toward the greenhouse effect.

John Sawyer published the study Man-made Carbon Dioxide and the “Greenhouse” Effect in 1972. He summarized the knowledge of the science at the time, the anthropogenic attribution of the carbon dioxide greenhouse gas, distribution and exponential rise, findings which still hold today. Additionally he accurately predicted the rate of global warming for the period between 1972 and 2000.

The increase of 25% CO2 expected by the end of the century therefore corresponds to an increase of 0.6°C in the world temperature – an amount somewhat greater than the climatic variation of recent centuries. – John Sawyer, 1972

The first satellite records compiled in the early 1970s showed snow and ice cover over the Northern Hemisphere to be increasing, prompting further scrutiny into the possibility of global cooling. J. Murray Mitchell updated his global temperature reconstruction in 1972, which continued to show cooling. However, scientists determined that the cooling observed by Mitchell was not a global phenomenon. Global averages were changing, largely in part due to unusually severe winters experienced by Asia and some parts of North America in 1972 and 1973, but these changes were mostly constrained to the Northern Hemisphere. In the Southern Hemisphere, the opposite trend was observed. The severe winters, however, pushed the issue of global cooling into the public eye.

The mainstream news media at the time exaggerated the warnings of the minority who expected imminent cooling. For example, in 1975, Newsweek magazine published a story titled “The Cooling World” that warned of "ominous signs that the Earth's weather patterns have begun to change." The article drew on studies documenting the increasing snow and ice in regions of the Northern Hemisphere and concerns and claims by Reid Bryson that global cooling by aerosols would dominate carbon dioxide warming. The article continued by stating that evidence of global cooling was so strong that meteorologists were having "a hard time keeping up with it." On 23 October 2006, Newsweek issued an update stating that it had been "spectacularly wrong about the near-term future". Nevertheless, this article and others like it had long-lasting effects on public perception of climate science.

Such media coverage heralding the coming of a new ice age resulted in beliefs that this was the consensus among scientists, despite this is not being reflected by the scientific literature. As it became apparent that scientific opinion was in favor of global warming, the public began to express doubt over how trustworthy the science was. The argument that scientists were wrong about global cooling, so therefore may be wrong about global warming has been called “the “Ice Age Fallacy” by TIME author Bryan Walsh.

In the first two "Reports for the Club of Rome" in 1972 and 1974, the anthropogenic climate changes by CO

2 increase as well as by waste heat were mentioned. About the latter John Holdren wrote in a study

cited in the 1st report, “… that global thermal pollution is hardly our

most immediate environmental threat. It could prove to be the most

inexorable, however, if we are fortunate enough to evade all the rest.”

Simple global-scale estimates that recently have been actualized and confirmed by more refined model calculations

show noticeable contributions from waste heat to global warming after

the year 2100, if its growth rates are not strongly reduced (below the

averaged 2% p.a. which occurred since 1973).

Evidence for warming accumulated. By 1975, Manabe and Wetherald had developed a three-dimensional Global climate model that gave a roughly accurate representation of the current climate. Doubling CO

2 in the model's atmosphere gave a roughly 2 °C rise in global temperature.

Several other kinds of computer models gave similar results: it was

impossible to make a model that gave something resembling the actual

climate and not have the temperature rise when the CO

2 concentration was increased.

In a separate development, an analysis of deep-sea cores published in 1976 by Nicholas Shackleton and colleagues showed that the dominating influence on ice age timing came from a 100,000-year Milankovitch orbital change. This was unexpected, since the change in sunlight in that cycle was slight. The result emphasized that the climate system is driven by feedbacks, and thus is strongly susceptible to small changes in conditions.

The 1979 World Climate Conference (12 to 23 February) of the World Meteorological Organization concluded "it appears plausible that an increased amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can contribute to a gradual warming of the lower atmosphere, especially at higher latitudes....It is possible that some effects on a regional and global scale may be detectable before the end of this century and become significant before the middle of the next century."

In July 1979 the United States National Research Council published a report, concluding (in part):

When it is assumed that the CO

2 content of the atmosphere is doubled and statistical thermal equilibrium is achieved, the more realistic of the modeling efforts predict a global surface warming of between 2°C and 3.5°C, with greater increases at high latitudes. ... we have tried but have been unable to find any overlooked or underestimated physical effects that could reduce the currently estimated global warmings due to a doubling of atmospheric CO

2 to negligible proportions or reverse them altogether.

Consensus begins to form, 1980–1988

By the early 1980s, the slight cooling trend from 1945 to 1975 had stopped. Aerosol pollution had decreased in many areas due to environmental legislation and changes in fuel use, and it became clear that the cooling effect from aerosols was not going to increase substantially while carbon dioxide levels were progressively increasing.

Hansen and others published the 1981 study Climate impact of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and noted:

It is shown that the anthropogenic carbon dioxide warming should emerge from the noise level of natural climate variability by the end of the century, and there is a high probability of warming in the 1980s. Potential effects on climate in the 21st century include the creation of drought-prone regions in North America and central Asia as part of a shifting of climatic zones, erosion of the West Antarctic ice sheet with a consequent worldwide rise in sea level, and opening of the fabled Northwest Passage.

In 1982, Greenland ice cores drilled by Hans Oeschger, Willi Dansgaard, and collaborators revealed dramatic temperature oscillations in the space of a century in the distant past. The most prominent of the changes in their record corresponded to the violent Younger Dryas climate oscillation seen in shifts in types of pollen in lake beds all over Europe. Evidently drastic climate changes were possible within a human lifetime.

In 1973 James Lovelock speculated that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could have a global warming effect. In 1975 V. Ramanathan

found that a CFC molecule could be 10,000 times more effective in

absorbing infrared radiation than a carbon dioxide molecule, making CFCs

potentially important despite their very low concentrations in the

atmosphere. While most early work on CFCs focused on their role in ozone depletion,

by 1985 Ramanathan and others showed that CFCs together with methane

and other trace gases could have nearly as important a climate effect as

increases in CO

2. In other words, global warming would arrive twice as fast as had been expected.

In 1985 a joint UNEP/WMO/ICSU Conference on the "Assessment of the Role of Carbon Dioxide and Other Greenhouse Gases in Climate Variations and Associated Impacts" concluded that greenhouse gases "are expected" to cause significant warming in the next century and that some warming is inevitable.

Meanwhile, ice cores drilled by a Franco-Soviet team at the Vostok Station in Antarctica showed that CO

2 and temperature had gone up and down together in wide swings through past ice ages. This confirmed the CO

2-temperature

relationship in a manner entirely independent of computer climate

models, strongly reinforcing the emerging scientific consensus. The

findings also pointed to powerful biological and geochemical feedbacks.

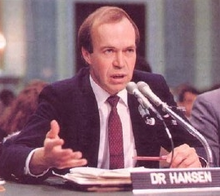

In June 1988, James E. Hansen made one of the first assessments that human-caused warming had already measurably affected global climate. Shortly after, a "World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere: Implications for Global Security" gathered hundreds of scientists and others in Toronto. They concluded that the changes in the atmosphere due to human pollution "represent a major threat to international security and are already having harmful consequences over many parts of the globe," and declared that by 2005 the world would be well-advised to push its emissions some 20% below the 1988 level.

The 1980s saw important breakthroughs with regard to global environmental challenges. Ozone depletion was mitigated by the Vienna Convention (1985) and the Montreal Protocol (1987). Acid rain was mainly regulated on national and regional levels.

Modern period: 1988 to present

In 1988 the WMO established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change with the support of the UNEP. The IPCC continues its work through the present day, and issues a series of Assessment Reports and supplemental reports that describe the state of scientific understanding at the time each report is prepared. Scientific developments during this period are summarized about once every five to six years in the IPCC Assessment Reports which were published in 1990 (First Assessment Report), 1995 (Second Assessment Report), 2001 (Third Assessment Report), 2007 (Fourth Assessment Report), and 2013/2014 (Fifth Assessment Report).

Since the 1990s, research on climate change has expanded and grown, linking many fields such as atmospheric sciences, numerical modeling, behavioral sciences, geology and economics, or security.

Discovery of other climate changing factors

Methane: In 1859, John Tyndall determined that coal gas, a mix of methane and other gases, strongly absorbed infrared radiation. Methane was subsequently detected in the atmosphere in 1948, and in the 1980s scientists realized that human emissions were having a substantial impact.

Chlorofluorocarbon: In 1973, British scientist James Lovelock speculated that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could have a global warming effect. In 1975, V. Ramanathan found that a CFC molecule could be 10,000 times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation than a carbon dioxide molecule, making CFCs potentially important despite their very low concentrations in the atmosphere. While most early work on CFCs focused on their role in ozone depletion, by 1985 scientists had concluded that CFCs together with methane and other trace gases could have nearly as important a climate effect as increases in CO2.