Hipparchus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 190 BC |

| Died | c. 120 BC (around age 70) |

| Occupation | |

Hipparchus of Nicaea (/hɪˈpɑːrkəs/; Greek: Ἵππαρχος, Hipparkhos; c. 190 – c. 120 BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of precession of the equinoxes. Hipparchus was born in Nicaea, Bithynia, and probably died on the island of Rhodes, Greece. He is known to have been a working astronomer between 162 and 127 BC.

Hipparchus is considered the greatest ancient astronomical observer and, by some, the greatest overall astronomer of antiquity. He was the first whose quantitative and accurate models for the motion of the Sun and Moon survive. For this he certainly made use of the observations and perhaps the mathematical techniques accumulated over centuries by the Babylonians and by Meton of Athens (fifth century BC), Timocharis, Aristyllus, Aristarchus of Samos, and Eratosthenes, among others.

He developed trigonometry and constructed trigonometric tables, and he solved several problems of spherical trigonometry. With his solar and lunar theories and his trigonometry, he may have been the first to develop a reliable method to predict solar eclipses.

His other reputed achievements include the discovery and measurement of Earth's precession, the compilation of the first comprehensive star catalog of the western world, and possibly the invention of the astrolabe, also of the armillary sphere that he used during the creation of much of the star catalogue. Sometimes Hipparchus is referred to as the "father of astronomy", a title first conferred on him by Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre.

Life and work

Hipparchus was born in Nicaea (Greek Νίκαια), in Bithynia. The exact dates of his life are not known, but Ptolemy attributes astronomical observations to him in the period from 147–127 BC, and some of these are stated as made in Rhodes; earlier observations since 162 BC might also have been made by him. His birth date (c. 190 BC) was calculated by Delambre based on clues in his work. Hipparchus must have lived some time after 127 BC because he analyzed and published his observations from that year. Hipparchus obtained information from Alexandria as well as Babylon, but it is not known when or if he visited these places. He is believed to have died on the island of Rhodes, where he seems to have spent most of his later life.

In the second and third centuries, coins were made in his honour in Bithynia that bear his name and show him with a globe.

Relatively little of Hipparchus's direct work survives into modern times. Although he wrote at least fourteen books, only his commentary on the popular astronomical poem by Aratus was preserved by later copyists. Most of what is known about Hipparchus comes from Strabo's Geography and Pliny's Natural History in the first century; Ptolemy's second-century Almagest; and additional references to him in the fourth century by Pappus and Theon of Alexandria in their commentaries on the Almagest.

Hipparchus was amongst the first to calculate a heliocentric system, but he abandoned his work because the calculations showed the orbits were not perfectly circular as believed to be mandatory by the science of the time. Although a contemporary of Hipparchus', Seleucus of Seleucia, remained a proponent of the heliocentric model, Hipparchus' rejection of heliocentrism was supported by ideas from Aristotle and remained dominant for nearly 2000 years until Copernican heliocentrism turned the tide of the debate.

Hipparchus's only preserved work is Τῶν Ἀράτου καὶ Εὐδόξου φαινομένων ἐξήγησις ("Commentary on the Phaenomena of Eudoxus and Aratus"). This is a highly critical commentary in the form of two books on a popular poem by Aratus based on the work by Eudoxus. Hipparchus also made a list of his major works that apparently mentioned about fourteen books, but which is only known from references by later authors. His famous star catalog was incorporated into the one by Ptolemy and may be almost perfectly reconstructed by subtraction of two and two-thirds degrees from the longitudes of Ptolemy's stars. The first trigonometric table was apparently compiled by Hipparchus, who is consequently now known as "the father of trigonometry".

Babylonian sources

Earlier Greek astronomers and mathematicians were influenced by Babylonian astronomy to some extent, for instance the period relations of the Metonic cycle and Saros cycle may have come from Babylonian sources (see "Babylonian astronomical diaries"). Hipparchus seems to have been the first to exploit Babylonian astronomical knowledge and techniques systematically. Eudoxus in the -4th century and Timocharis and Aristillus in the -3rd century already divided the ecliptic in 360 parts (our degrees, Greek: moira) of 60 arcminutes and Hipparchus continued this tradition. It was only in Hipparchus' time (-2nd century) when this division was introduced (probably by Hipparchus' contemporary Hypsikles) for all circles in mathematics. Eratosthenes (-3rd century), in contrast, used a simpler sexagesimal system dividing a circle into 60 parts. He also adopted the Babylonian astronomical cubit unit (Akkadian ammatu, Greek πῆχυς pēchys) that was equivalent to 2° or 2.5° ('large cubit').

Hipparchus probably compiled a list of Babylonian astronomical observations; G. J. Toomer, a historian of astronomy, has suggested that Ptolemy's knowledge of eclipse records and other Babylonian observations in the Almagest came from a list made by Hipparchus. Hipparchus's use of Babylonian sources has always been known in a general way, because of Ptolemy's statements, but the only text by Hipparchus that survives does not provide suffient information to decide whether Hipparchus' knowledge (such as his usage of the units cubit and finger, degrees and minutes, or the concept of hour stars) was based on Babylonian practie. However, Franz Xaver Kugler demonstrated that the synodic and anomalistic periods that Ptolemy attributes to Hipparchus had already been used in Babylonian ephemerides, specifically the collection of texts nowadays called "System B" (sometimes attributed to Kidinnu).

Hipparchus's long draconitic lunar period (5,458 months = 5,923 lunar nodal periods) also appears a few times in Babylonian records. But the only such tablet explicitly dated, is post-Hipparchus so the direction of transmission is not settled by the tablets.

Hipparchus's draconitic lunar motion cannot be solved by the lunar-four arguments sometimes proposed to explain his anomalistic motion. A solution that has produced the exact 5,458⁄5,923 ratio is rejected by most historians although it uses the only anciently attested method of determining such ratios, and it automatically delivers the ratio's four-digit numerator and denominator. Hipparchus initially used (Almagest 6.9) his 141 BC eclipse with a Babylonian eclipse of 720 BC to find the less accurate ratio 7,160 synodic months = 7,770 draconitic months, simplified by him to 716 = 777 through division by 10. (He similarly found from the 345-year cycle the ratio 4,267 synodic months = 4,573 anomalistic months and divided by 17 to obtain the standard ratio 251 synodic months = 269 anomalistic months.) If he sought a longer time base for this draconitic investigation he could use his same 141 BC eclipse with a moonrise 1245 BC eclipse from Babylon, an interval of 13,645 synodic months = 14,8807+1⁄2 draconitic months ≈ 14,623+1⁄2 anomalistic months. Dividing by 5⁄2 produces 5,458 synodic months = 5,923 precisely. The obvious main objection is that the early eclipse is unattested, although that is not surprising in itself, and there is no consensus on whether Babylonian observations were recorded this remotely. Though Hipparchus's tables formally went back only to 747 BC, 600 years before his era, the tables were good back to before the eclipse in question because as only recently noted, their use in reverse is no more difficult than forward.

Geometry, trigonometry and other mathematical techniques

Hipparchus was recognized as the first mathematician known to have possessed a trigonometric table, which he needed when computing the eccentricity of the orbits of the Moon and Sun. He tabulated values for the chord function, which for a central angle in a circle gives the length of the straight line segment between the points where the angle intersects the circle. He computed this for a circle with a circumference of 21,600 units and a radius (rounded) of 3,438 units; this circle has a unit length of 1 arcminute along its perimeter. He tabulated the chords for angles with increments of 7.5°. In modern terms, the chord subtended by a central angle in a circle of given radius equals the radius times twice the sine of half of the angle, i.e.:

The now-lost work in which Hipparchus is said to have developed his chord table, is called Tōn en kuklōi eutheiōn (Of Lines Inside a Circle) in Theon of Alexandria's fourth-century commentary on section I.10 of the Almagest. Some claim the table of Hipparchus may have survived in astronomical treatises in India, such as the Surya Siddhanta. Trigonometry was a significant innovation, because it allowed Greek astronomers to solve any triangle, and made it possible to make quantitative astronomical models and predictions using their preferred geometric techniques.

Hipparchus must have used a better approximation for π than the one from Archimedes of between 3+10⁄71 (3.14085) and 3+1⁄7 (3.14286). Perhaps he had the one later used by Ptolemy: 3;8,30 (sexagesimal)(3.1417) (Almagest VI.7), but it is not known whether he computed an improved value.

Some scholars do not believe Āryabhaṭa's sine table has anything to do with Hipparchus's chord table. Others do not agree that Hipparchus even constructed a chord table. Bo C. Klintberg states, "With mathematical reconstructions and philosophical arguments I show that Toomer's 1973 paper never contained any conclusive evidence for his claims that Hipparchus had a 3438'-based chord table, and that the Indians used that table to compute their sine tables. Recalculating Toomer's reconstructions with a 3600' radius—i.e. the radius of the chord table in Ptolemy's Almagest, expressed in 'minutes' instead of 'degrees'—generates Hipparchan-like ratios similar to those produced by a 3438′ radius. Therefore, it is possible that the radius of Hipparchus's chord table was 3600′, and that the Indians independently constructed their 3438′-based sine table."

Hipparchus could have constructed his chord table using the Pythagorean theorem and a theorem known to Archimedes. He also might have developed and used the theorem called Ptolemy's theorem; this was proved by Ptolemy in his Almagest (I.10) (and later extended by Carnot).

Hipparchus was the first to show that the stereographic projection is conformal, and that it transforms circles on the sphere that do not pass through the center of projection to circles on the plane. This was the basis for the astrolabe.

Besides geometry, Hipparchus also used arithmetic techniques developed by the Chaldeans. He was one of the first Greek mathematicians to do this and, in this way, expanded the techniques available to astronomers and geographers.

There are several indications that Hipparchus knew spherical trigonometry, but the first surviving text discussing it is by Menelaus of Alexandria in the first century, who now, on that basis, commonly is credited with its discovery. (Previous to the finding of the proofs of Menelaus a century ago, Ptolemy was credited with the invention of spherical trigonometry.) Ptolemy later used spherical trigonometry to compute things such as the rising and setting points of the ecliptic, or to take account of the lunar parallax. If he did not use spherical trigonometry, Hipparchus may have used a globe for these tasks, reading values off coordinate grids drawn on it, or he may have made approximations from planar geometry, or perhaps used arithmetical approximations developed by the Chaldeans.

Aubrey Diller has shown that the clima calculations that Strabo preserved from Hipparchus could have been performed by spherical trigonometry using the only accurate obliquity known to have been used by ancient astronomers, 23°40′. All thirteen clima figures agree with Diller's proposal. Further confirming his contention is the finding that the big errors in Hipparchus's longitude of Regulus and both longitudes of Spica, agree to a few minutes in all three instances with a theory that he took the wrong sign for his correction for parallax when using eclipses for determining stars' positions.

Lunar and solar theory

Motion of the Moon

Hipparchus also studied the motion of the Moon and confirmed the accurate values for two periods of its motion that Chaldean astronomers are widely presumed to have possessed before him, whatever their ultimate origin. The traditional value (from Babylonian System B) for the mean synodic month is 29 days; 31,50,8,20 (sexagesimal) = 29.5305941... days. Expressed as 29 days + 12 hours + 793/1080 hours this value has been used later in the Hebrew calendar. The Chaldeans also knew that 251 synodic months ≈ 269 anomalistic months. Hipparchus used the multiple of this period by a factor of 17, because that interval is also an eclipse period, and is also close to an integer number of years (4,267 moons : 4,573 anomalistic periods : 4,630.53 nodal periods : 4,611.98 lunar orbits : 344.996 years : 344.982 solar orbits : 126,007.003 days : 126,351.985 rotations). What was so exceptional and useful about the cycle was that all 345-year-interval eclipse pairs occur slightly more than 126,007 days apart within a tight range of only about ±1⁄2 hour, guaranteeing (after division by 4,267) an estimate of the synodic month correct to one part in order of magnitude 10 million. The 345-year periodicity is why the ancients could conceive of a mean month and quantify it so accurately that it is correct, even today, to a fraction of a second of time.

Hipparchus could confirm his computations by comparing eclipses from his own time (presumably 27 January 141 BC and 26 November 139 BC according to [Toomer 1980]), with eclipses from Babylonian records 345 years earlier (Almagest IV.2; [A.Jones, 2001]). Already al-Biruni (Qanun VII.2.II) and Copernicus (de revolutionibus IV.4) noted that the period of 4,267 moons is approximately five minutes longer than the value for the eclipse period that Ptolemy attributes to Hipparchus. However, the timing methods of the Babylonians had an error of no fewer than eight minutes. Modern scholars agree that Hipparchus rounded the eclipse period to the nearest hour, and used it to confirm the validity of the traditional values, rather than to try to derive an improved value from his own observations. From modern ephemerides and taking account of the change in the length of the day (see ΔT) we estimate that the error in the assumed length of the synodic month was less than 0.2 second in the fourth century BC and less than 0.1 second in Hipparchus's time.

Orbit of the Moon

It had been known for a long time that the motion of the Moon is not uniform: its speed varies. This is called its anomaly and it repeats with its own period; the anomalistic month. The Chaldeans took account of this arithmetically, and used a table giving the daily motion of the Moon according to the date within a long period. However, the Greeks preferred to think in geometrical models of the sky. At the end of the third century BC, Apollonius of Perga had proposed two models for lunar and planetary motion:

- In the first, the Moon would move uniformly along a circle, but the Earth would be eccentric, i.e., at some distance of the center of the circle. So the apparent angular speed of the Moon (and its distance) would vary.

- The Moon would move uniformly (with some mean motion in anomaly) on a secondary circular orbit, called an epicycle that would move uniformly (with some mean motion in longitude) over the main circular orbit around the Earth, called deferent; see deferent and epicycle. Apollonius demonstrated that these two models were in fact mathematically equivalent. However, all this was theory and had not been put to practice. Hipparchus is the first astronomer known to attempt to determine the relative proportions and actual sizes of these orbits.

Hipparchus devised a geometrical method to find the parameters from three positions of the Moon at particular phases of its anomaly. In fact, he did this separately for the eccentric and the epicycle model. Ptolemy describes the details in the Almagest IV.11. Hipparchus used two sets of three lunar eclipse observations that he carefully selected to satisfy the requirements. The eccentric model he fitted to these eclipses from his Babylonian eclipse list: 22/23 December 383 BC, 18/19 June 382 BC, and 12/13 December 382 BC. The epicycle model he fitted to lunar eclipse observations made in Alexandria at 22 September 201 BC, 19 March 200 BC, and 11 September 200 BC.

- For the eccentric model, Hipparchus found for the ratio between the radius of the eccenter and the distance between the center of the eccenter and the center of the ecliptic (i.e., the observer on Earth): 3144 : 327+2⁄3 ;

- and for the epicycle model, the ratio between the radius of the deferent and the epicycle: 3122+1⁄2 : 247+1⁄2 .

The somewhat weird numbers are due to the cumbersome unit he used in his chord table according to one group of historians, who explain their reconstruction's inability to agree with these four numbers as partly due to some sloppy rounding and calculation errors by Hipparchus, for which Ptolemy criticised him while also making rounding errors. A simpler alternate reconstruction agrees with all four numbers. Anyway, Hipparchus found inconsistent results; he later used the ratio of the epicycle model (3122+1⁄2 : 247+1⁄2), which is too small (60 : 4;45 sexagesimal). Ptolemy established a ratio of 60 : 5+1⁄4. (The maximum angular deviation producible by this geometry is the arcsin of 5+1⁄4 divided by 60, or approximately 5° 1', a figure that is sometimes therefore quoted as the equivalent of the Moon's equation of the center in the Hipparchan model.)

Apparent motion of the Sun

Before Hipparchus, Meton, Euctemon, and their pupils at Athens had made a solstice observation (i.e., timed the moment of the summer solstice) on 27 June 432 BC (proleptic Julian calendar). Aristarchus of Samos is said to have done so in 280 BC, and Hipparchus also had an observation by Archimedes. As shown in a 1991 paper, in 158 BC Hipparchus computed a very erroneous summer solstice from Callippus's calendar. He observed the summer solstice in 146 and 135 BC both accurate to a few hours, but observations of the moment of equinox were simpler, and he made twenty during his lifetime. Ptolemy gives an extensive discussion of Hipparchus's work on the length of the year in the Almagest III.1, and quotes many observations that Hipparchus made or used, spanning 162–128 BC. Analysis of Hipparchus's seventeen equinox observations made at Rhodes shows that the mean error in declination is positive seven arc minutes, nearly agreeing with the sum of refraction by air and Swerdlow's parallax. The random noise is two arc minutes or more nearly one arcminute if rounding is taken into account which approximately agrees with the sharpness of the eye. Ptolemy quotes an equinox timing by Hipparchus (at 24 March 146 BC at dawn) that differs by 5 hours from the observation made on Alexandria's large public equatorial ring that same day (at 1 hour before noon): Hipparchus may have visited Alexandria but he did not make his equinox observations there; presumably he was on Rhodes (at nearly the same geographical longitude). Ptolemy claims his solar observations were on a transit instrument set in the meridian.

Recent expert translation and analysis by Anne Tihon of papyrus P. Fouad 267 A has confirmed the 1991 finding cited above that Hipparchus obtained a summer solstice in 158 BC But the papyrus makes the date 26 June, over a day earlier than the 1991 paper's conclusion for 28 June. The earlier study's §M found that Hipparchus did not adopt 26 June solstices until 146 BC when he founded the orbit of the Sun which Ptolemy later adopted. Dovetailing these data suggests Hipparchus extrapolated the 158 BC 26 June solstice from his 145 solstice 12 years later a procedure that would cause only minuscule error. The papyrus also confirmed that Hipparchus had used Callippic solar motion in 158 BC, a new finding in 1991 but not attested directly until P. Fouad 267 A. Another table on the papyrus is perhaps for sidereal motion and a third table is for Metonic tropical motion, using a previously unknown year of 365+1⁄4—1⁄309 days. This was presumably found by dividing the 274 years from 432 to 158 BC, into the corresponding interval of 100,077 days and 14+3⁄4 hours between Meton's sunrise and Hipparchus's sunset solstices.

At the end of his career, Hipparchus wrote a book called Peri eniausíou megéthous ("On the Length of the Year") about his results. The established value for the tropical year, introduced by Callippus in or before 330 BC was 365+1⁄4 days. Speculating a Babylonian origin for the Callippic year is hard to defend, since Babylon did not observe solstices thus the only extant System B year length was based on Greek solstices (see below). Hipparchus's equinox observations gave varying results, but he himself points out (quoted in Almagest III.1(H195)) that the observation errors by himself and his predecessors may have been as large as 1⁄4 day. He used old solstice observations, and determined a difference of about one day in about 300 years. So he set the length of the tropical year to 365+1⁄4 − 1⁄300 days (= 365.24666... days = 365 days 5 hours 55 min, which differs from the actual value (modern estimate, including earth spin acceleration) in his time of about 365.2425 days, an error of about 6 min per year, an hour per decade, 10 hours per century.

Between the solstice observation of Meton and his own, there were 297 years spanning 108,478 days. D. Rawlins noted that this implies a tropical year of 365.24579... days = 365 days;14,44,51 (sexagesimal; = 365 days + 14/60 + 44/602 + 51/603) and that this exact year length has been found on one of the few Babylonian clay tablets which explicitly specifies the System B month. This is an indication that Hipparchus's work was known to Chaldeans.

Another value for the year that is attributed to Hipparchus (by the astrologer Vettius Valens in the 1st century) is 365 + 1/4 + 1/288 days (= 365.25347... days = 365 days 6 hours 5 min), but this may be a corruption of another value attributed to a Babylonian source: 365 + 1/4 + 1/144 days (= 365.25694... days = 365 days 6 hours 10 min). It is not clear if this would be a value for the sidereal year (actual value at his time (modern estimate) about 365.2565 days), but the difference with Hipparchus's value for the tropical year is consistent with his rate of precession (see below).

Orbit of the Sun

Before Hipparchus, astronomers knew that the lengths of the seasons are not equal. Hipparchus made observations of equinox and solstice, and according to Ptolemy (Almagest III.4) determined that spring (from spring equinox to summer solstice) lasted 94½ days, and summer (from summer solstice to autumn equinox) 92+1⁄2 days. This is inconsistent with a premise of the Sun moving around the Earth in a circle at uniform speed. Hipparchus's solution was to place the Earth not at the center of the Sun's motion, but at some distance from the center. This model described the apparent motion of the Sun fairly well. It is known today that the planets, including the Earth, move in approximate ellipses around the Sun, but this was not discovered until Johannes Kepler published his first two laws of planetary motion in 1609. The value for the eccentricity attributed to Hipparchus by Ptolemy is that the offset is 1⁄24 of the radius of the orbit (which is a little too large), and the direction of the apogee would be at longitude 65.5° from the vernal equinox. Hipparchus may also have used other sets of observations, which would lead to different values. One of his two eclipse trios' solar longitudes are consistent with his having initially adopted inaccurate lengths for spring and summer of 95+3⁄4 and 91+1⁄4 days. His other triplet of solar positions is consistent with 94+1⁄4 and 92+1⁄2 days, an improvement on the results (94+1⁄2 and 92+1⁄2 days) attributed to Hipparchus by Ptolemy, which a few scholars still question the authorship of. Ptolemy made no change three centuries later, and expressed lengths for the autumn and winter seasons which were already implicit (as shown, e.g., by A. Aaboe).

Distance, parallax, size of the Moon and the Sun

Hipparchus also undertook to find the distances and sizes of the Sun and the Moon. His results appear in two works: Perí megethōn kaí apostēmátōn ("On Sizes and Distances") by Pappus and in Pappus's commentary on the Almagest V.11; Theon of Smyrna (2nd century) mentions the work with the addition "of the Sun and Moon".

Hipparchus measured the apparent diameters of the Sun and Moon with his diopter. Like others before and after him, he found that the Moon's size varies as it moves on its (eccentric) orbit, but he found no perceptible variation in the apparent diameter of the Sun. He found that at the mean distance of the Moon, the Sun and Moon had the same apparent diameter; at that distance, the Moon's diameter fits 650 times into the circle, i.e., the mean apparent diameters are 360⁄650 = 0°33′14″.

Like others before and after him, he also noticed that the Moon has a noticeable parallax, i.e., that it appears displaced from its calculated position (compared to the Sun or stars), and the difference is greater when closer to the horizon. He knew that this is because in the then-current models the Moon circles the center of the Earth, but the observer is at the surface—the Moon, Earth and observer form a triangle with a sharp angle that changes all the time. From the size of this parallax, the distance of the Moon as measured in Earth radii can be determined. For the Sun however, there was no observable parallax (we now know that it is about 8.8", several times smaller than the resolution of the unaided eye).

In the first book, Hipparchus assumes that the parallax of the Sun is 0, as if it is at infinite distance. He then analyzed a solar eclipse, which Toomer (against the opinion of over a century of astronomers) presumes to be the eclipse of 14 March 190 BC. It was total in the region of the Hellespont (and in his birthplace, Nicaea); at the time Toomer proposes the Romans were preparing for war with Antiochus III in the area, and the eclipse is mentioned by Livy in his Ab Urbe Condita Libri VIII.2. It was also observed in Alexandria, where the Sun was reported to be obscured 4/5ths by the Moon. Alexandria and Nicaea are on the same meridian. Alexandria is at about 31° North, and the region of the Hellespont about 40° North. (It has been contended that authors like Strabo and Ptolemy had fairly decent values for these geographical positions, so Hipparchus must have known them too. However, Strabo's Hipparchus dependent latitudes for this region are at least 1° too high, and Ptolemy appears to copy them, placing Byzantium 2° high in latitude.) Hipparchus could draw a triangle formed by the two places and the Moon, and from simple geometry was able to establish a distance of the Moon, expressed in Earth radii. Because the eclipse occurred in the morning, the Moon was not in the meridian, and it has been proposed that as a consequence the distance found by Hipparchus was a lower limit. In any case, according to Pappus, Hipparchus found that the least distance is 71 (from this eclipse), and the greatest 81 Earth radii.

In the second book, Hipparchus starts from the opposite extreme assumption: he assigns a (minimum) distance to the Sun of 490 Earth radii. This would correspond to a parallax of 7′, which is apparently the greatest parallax that Hipparchus thought would not be noticed (for comparison: the typical resolution of the human eye is about 2′; Tycho Brahe made naked eye observation with an accuracy down to 1′). In this case, the shadow of the Earth is a cone rather than a cylinder as under the first assumption. Hipparchus observed (at lunar eclipses) that at the mean distance of the Moon, the diameter of the shadow cone is 2+1⁄2 lunar diameters. That apparent diameter is, as he had observed, 360⁄650 degrees. With these values and simple geometry, Hipparchus could determine the mean distance; because it was computed for a minimum distance of the Sun, it is the maximum mean distance possible for the Moon. With his value for the eccentricity of the orbit, he could compute the least and greatest distances of the Moon too. According to Pappus, he found a least distance of 62, a mean of 67+1⁄3, and consequently a greatest distance of 72+2⁄3 Earth radii. With this method, as the parallax of the Sun decreases (i.e., its distance increases), the minimum limit for the mean distance is 59 Earth radii—exactly the mean distance that Ptolemy later derived.

Hipparchus thus had the problematic result that his minimum distance (from book 1) was greater than his maximum mean distance (from book 2). He was intellectually honest about this discrepancy, and probably realized that especially the first method is very sensitive to the accuracy of the observations and parameters. (In fact, modern calculations show that the size of the 189 BC solar eclipse at Alexandria must have been closer to 9⁄10ths and not the reported 4⁄5ths, a fraction more closely matched by the degree of totality at Alexandria of eclipses occurring in 310 and 129 BC which were also nearly total in the Hellespont and are thought by many to be more likely possibilities for the eclipse Hipparchus used for his computations.)

Ptolemy later measured the lunar parallax directly (Almagest V.13), and used the second method of Hipparchus with lunar eclipses to compute the distance of the Sun (Almagest V.15). He criticizes Hipparchus for making contradictory assumptions, and obtaining conflicting results (Almagest V.11): but apparently he failed to understand Hipparchus's strategy to establish limits consistent with the observations, rather than a single value for the distance. His results were the best so far: the actual mean distance of the Moon is 60.3 Earth radii, within his limits from Hipparchus's second book.

Theon of Smyrna wrote that according to Hipparchus, the Sun is 1,880 times the size of the Earth, and the Earth twenty-seven times the size of the Moon; apparently this refers to volumes, not diameters. From the geometry of book 2 it follows that the Sun is at 2,550 Earth radii, and the mean distance of the Moon is 60+1⁄2 radii. Similarly, Cleomedes quotes Hipparchus for the sizes of the Sun and Earth as 1050:1; this leads to a mean lunar distance of 61 radii. Apparently Hipparchus later refined his computations, and derived accurate single values that he could use for predictions of solar eclipses.

See [Toomer 1974] for a more detailed discussion.

Eclipses

Pliny (Naturalis Historia II.X) tells us that Hipparchus demonstrated that lunar eclipses can occur five months apart, and solar eclipses seven months (instead of the usual six months); and the Sun can be hidden twice in thirty days, but as seen by different nations. Ptolemy discussed this a century later at length in Almagest VI.6. The geometry, and the limits of the positions of Sun and Moon when a solar or lunar eclipse is possible, are explained in Almagest VI.5. Hipparchus apparently made similar calculations. The result that two solar eclipses can occur one month apart is important, because this can not be based on observations: one is visible on the northern and the other on the southern hemisphere—as Pliny indicates—and the latter was inaccessible to the Greek.

Prediction of a solar eclipse, i.e., exactly when and where it will be visible, requires a solid lunar theory and proper treatment of the lunar parallax. Hipparchus must have been the first to be able to do this. A rigorous treatment requires spherical trigonometry, thus those who remain certain that Hipparchus lacked it must speculate that he may have made do with planar approximations. He may have discussed these things in Perí tēs katá plátos mēniaías tēs selēnēs kinēseōs ("On the monthly motion of the Moon in latitude"), a work mentioned in the Suda.

Pliny also remarks that "he also discovered for what exact reason, although the shadow causing the eclipse must from sunrise onward be below the earth, it happened once in the past that the Moon was eclipsed in the west while both luminaries were visible above the earth" (translation H. Rackham (1938), Loeb Classical Library 330 p. 207). Toomer (1980) argued that this must refer to the large total lunar eclipse of 26 November 139 BC, when over a clean sea horizon as seen from Rhodes, the Moon was eclipsed in the northwest just after the Sun rose in the southeast. This would be the second eclipse of the 345-year interval that Hipparchus used to verify the traditional Babylonian periods: this puts a late date to the development of Hipparchus's lunar theory. We do not know what "exact reason" Hipparchus found for seeing the Moon eclipsed while apparently it was not in exact opposition to the Sun. Parallax lowers the altitude of the luminaries; refraction raises them, and from a high point of view the horizon is lowered.

Astronomical instruments and astrometry

Hipparchus and his predecessors used various instruments for astronomical calculations and observations, such as the gnomon, the astrolabe, and the armillary sphere.

Hipparchus is credited with the invention or improvement of several astronomical instruments, which were used for a long time for naked-eye observations. According to Synesius of Ptolemais (4th century) he made the first astrolabion: this may have been an armillary sphere (which Ptolemy however says he constructed, in Almagest V.1); or the predecessor of the planar instrument called astrolabe (also mentioned by Theon of Alexandria). With an astrolabe Hipparchus was the first to be able to measure the geographical latitude and time by observing fixed stars. Previously this was done at daytime by measuring the shadow cast by a gnomon, by recording the length of the longest day of the year or with the portable instrument known as a scaphe.

Ptolemy mentions (Almagest V.14) that he used a similar instrument as Hipparchus, called dioptra, to measure the apparent diameter of the Sun and Moon. Pappus of Alexandria described it (in his commentary on the Almagest of that chapter), as did Proclus (Hypotyposis IV). It was a four-foot rod with a scale, a sighting hole at one end, and a wedge that could be moved along the rod to exactly obscure the disk of Sun or Moon.

Hipparchus also observed solar equinoxes, which may be done with an equatorial ring: its shadow falls on itself when the Sun is on the equator (i.e., in one of the equinoctial points on the ecliptic), but the shadow falls above or below the opposite side of the ring when the Sun is south or north of the equator. Ptolemy quotes (in Almagest III.1 (H195)) a description by Hipparchus of an equatorial ring in Alexandria; a little further he describes two such instruments present in Alexandria in his own time.

Hipparchus applied his knowledge of spherical angles to the problem of denoting locations on the Earth's surface. Before him a grid system had been used by Dicaearchus of Messana, but Hipparchus was the first to apply mathematical rigor to the determination of the latitude and longitude of places on the Earth. Hipparchus wrote a critique in three books on the work of the geographer Eratosthenes of Cyrene (3rd century BC), called Pròs tèn Eratosthénous geographían ("Against the Geography of Eratosthenes"). It is known to us from Strabo of Amaseia, who in his turn criticised Hipparchus in his own Geographia. Hipparchus apparently made many detailed corrections to the locations and distances mentioned by Eratosthenes. It seems he did not introduce many improvements in methods, but he did propose a means to determine the geographical longitudes of different cities at lunar eclipses (Strabo Geographia 1 January 2012). A lunar eclipse is visible simultaneously on half of the Earth, and the difference in longitude between places can be computed from the difference in local time when the eclipse is observed. His approach would give accurate results if it were correctly carried out but the limitations of timekeeping accuracy in his era made this method impractical.

Star catalog

Late in his career (possibly about 135 BC) Hipparchus compiled his star catalog, the original of which does not survive. He also constructed a celestial globe depicting the constellations, based on his observations. His interest in the fixed stars may have been inspired by the observation of a supernova (according to Pliny), or by his discovery of precession, according to Ptolemy, who says that Hipparchus could not reconcile his data with earlier observations made by Timocharis and Aristillus. For more information see Discovery of precession. In Raphael's painting The School of Athens, Hipparchus is depicted holding his celestial globe, as the representative figure for astronomy.

Previously, Eudoxus of Cnidus in the 4th century BCE had described the stars and constellations in two books called Phaenomena and Entropon. Aratus wrote a poem called Phaenomena or Arateia based on Eudoxus's work. Hipparchus wrote a commentary on the Arateia—his only preserved work—which contains many stellar positions and times for rising, culmination, and setting of the constellations, and these are likely to have been based on his own measurements.

According to Roman sources, Hipparchus made his measurements with a scientific instrument and he obtained the positions of roughly 850 stars. Pliny the Elder writes in book II, 24–26 of his Natural History:

This same Hipparchus, who can never be sufficiently commended, (...), discovered a new star that was produced in his own age, and, by observing its motions on the day in which it shone, he was led to doubt whether it does not often happen, that those stars have motion which we suppose to be fixed. And the same individual attempted, what might seem presumptuous even in a deity, viz. to number the stars for posterity and to express their relations by appropriate names; having previously devised instruments, by which he might mark the places and the magnitudes of each individual star. In this way it might be easily discovered, not only whether they were destroyed or produced, but whether they changed their relative positions, and likewise, whether they were increased or diminished; the heavens being thus left as an inheritance to any one, who might be found competent to complete his plan.

This quote reports that

- Hipparchus was inspired by a newly emerging star

- he doubts on the stability of stellar brightnesses

- that he observed with appropriate instruments (plural - it is not said that he observed everything with the same instrument)

- made a catalogue of stars

It is unknown what instrument he used. The armillary sphere was probably invented only later - maybe by Ptolemy only 265 years after Hipparchus. The historian of science S. Hoffmann found prove that Hipparchus observed the "longitudes" and "latitudes" in different coordinate systems and, thus, with different instrumentation. Right ascensions, for instance, could have been obsverd with a clock while angular separations could have been measured with another device.

Stellar magnitude

Hipparchus is conjectured to have ranked the apparent magnitudes of stars on a numerical scale from 1, the brightest, to 6, the faintest. This hypothesis is based on the vague statement by Pliny the Elder but cannot be proven by the data in Hipparchus' commentary on Aratus' poem. In this only work by his hand that has survived until today, he does not use the magnitude scale but estimates brightnesses unsystematically. However, this does not prove or disprove anything because the commentary might be an early work while the magnitude scale could have been introduced later. It is unknown who invented this method.

Nevertheless, this system certainly precedes Ptolemy, who used it extensively about AD 150. This system was made more precise and extended by N. R. Pogson in 1856, who placed the magnitudes on a logarithmic scale, making magnitude 1 stars 100 times brighter than magnitude 6 stars, thus each magnitude is 5√100 or 2.512 times brighter than the next faintest magnitude.

Coordinate System

It is disputed which coordinate system(s) he used. Ptolemy's catalog in the Almagest, which is derived from Hipparchus's catalog, is given in ecliptic coordinates. Although Hipparchus strictly distinguishes between "signs" (30°-section of the zodiac) and "constellations" in the zodiac, it is highly questionable whether or not he had an instrument to directly observe / measure units on the ecliptic. He probably marked them as a unit on his celestial globe but the instrumentation for his observations is unknown.

Delambre in his Histoire de l'Astronomie Ancienne (1817) concluded that Hipparchus knew and used the equatorial coordinate system, a conclusion challenged by Otto Neugebauer in his A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy (1975). Hipparchus seems to have used a mix of ecliptic coordinates and equatorial coordinates: in his commentary on Eudoxos he provides stars' polar distance (equivalent to the declination in the equatorial system), right ascension (equatorial), longitude (ecliptical), polar longitude (hybrid), but not celestial latitude. This opinion was confirmed by the careful investigation of Hoffmann who independently studied the material, potential sources, techniques and results of Hipparchus and reconstructed his celestial globe and its making.

As with most of his work, Hipparchus's star catalog was adopted and perhaps expanded by Ptolemy. Delambre, in 1817, cast doubt on Ptolemy's work. It was disputed whether the star catalog in the Almagest is due to Hipparchus, but 1976–2002 statistical and spatial analyses (by R. R. Newton, Dennis Rawlins, Gerd Grasshoff, Keith Pickering and Dennis Duke) have shown conclusively that the Almagest star catalog is almost entirely Hipparchan. Ptolemy has even (since Brahe, 1598) been accused by astronomers of fraud for stating (Syntaxis, book 7, chapter 4) that he observed all 1025 stars: for almost every star he used Hipparchus's data and precessed it to his own epoch 2+2⁄3 centuries later by adding 2°40' to the longitude, using an erroneously small precession constant of 1° per century. This claim is highly exaggerated because it applies modern standards of citation to an ancient author. True is only that "the ancient star catalogue" that was initiated by Hipparchus in the 2nd century BCE, was reworked and improved multiple times in the 265 years to the Almagest (which is good scientific practise until today). Although the Almagest star catalogue is a based upon Hipparchus' one, it is not only a blind copy but enriched, enhanced, and thus (at least partially) re-observed.

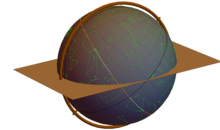

Celestial globe

Hipparchus' celestial globe was an instrument similar to modern electronic computers. He used it to determin risings, settings and culminations (cf. also Almagest, book VIII, chapter 3). Therefore, his globe was mounted in a horizontal plane and had a meridian ring with a scale. In combination with a grid that divided the celestial equator into 24 hour lines (longitudes equalling our right ascension hours) the instrument allowed him to determine the hours. THe ecliptic was marked and dvided in 12 sections of equal length (the "signs", which he called "zodion" or "dodekatemoria" in order to distinguish them from constellations ("astron"). The globe was virtually reconstructed by a historian of science.

In any case the work started by Hipparchus has had a lasting heritage, and was much later updated by al-Sufi (964) and Copernicus (1543). Ulugh Beg reobserved all the Hipparchus stars he could see from Samarkand in 1437 to about the same accuracy as Hipparchus's. The catalog was superseded only in the late 16th century by Brahe and Wilhelm IV of Kassel via superior ruled instruments and spherical trigonometry, which improved accuracy by an order of magnitude even before the invention of the telescope. Hipparchus is considered the greatest observational astronomer from classical antiquity until Brahe.

Arguments for and against Hipparchus' star catalog in the Almagest

Pro

- common errors in the reconstructed Hipparchian star catalogue and the Almagest suggest a direct transfer without re-observation within 265 years. There are 18 stars with common errors - for the other ~800 stars, the errors are not extant or within the error ellipse. That means, no further statement is allowed on these hundreds of stars.

- further statistical arguments

Contra

- Unlike Ptolemy, Hipparchus did not use ecliptical coordinates to decribe stellar positions.

- Hipparchus' catalogue is reported in Roman times to have enlisted ~850 stars but Ptolemy's catalogue has 1025 stars. Thus, somebody has added further entries.

- There are stars cited in the Almagest from Hipparchus that are missing in the Almagest star catalogue. Thus, by all the reworking within scientific progress in 265 years, not all of Hipparchus' stars made it into the Almagest version of the star catalogue.

Conclusion: Hipparchus' star catalogue is one of the sources of the Almagest star catalogue but not the only source.

Precession of the equinoxes (146–127 BC)

Hipparchus is generally recognized as discoverer of the precession of the equinoxes in 127 BC. His two books on precession, On the Displacement of the Solsticial and Equinoctial Points and On the Length of the Year, are both mentioned in the Almagest of Claudius Ptolemy. According to Ptolemy, Hipparchus measured the longitude of Spica and Regulus and other bright stars. Comparing his measurements with data from his predecessors, Timocharis and Aristillus, he concluded that Spica had moved 2° relative to the autumnal equinox. He also compared the lengths of the tropical year (the time it takes the Sun to return to an equinox) and the sidereal year (the time it takes the Sun to return to a fixed star), and found a slight discrepancy. Hipparchus concluded that the equinoxes were moving ("precessing") through the zodiac, and that the rate of precession was not less than 1° in a century.

Geography

Hipparchus's treatise Against the Geography of Eratosthenes in three books is not preserved. Most of our knowledge of it comes from Strabo, according to whom Hipparchus thoroughly and often unfairly criticized Eratosthenes, mainly for internal contradictions and inaccuracy in determining positions of geographical localities. Hipparchus insists that a geographic map must be based only on astronomical measurements of latitudes and longitudes and triangulation for finding unknown distances. In geographic theory and methods Hipparchus introduced three main innovations.

He was the first to use the grade grid, to determine geographic latitude from star observations, and not only from the Sun's altitude, a method known long before him, and to suggest that geographic longitude could be determined by means of simultaneous observations of lunar eclipses in distant places. In the practical part of his work, the so-called "table of climata", Hipparchus listed latitudes for several tens of localities. In particular, he improved Eratosthenes' values for the latitudes of Athens, Sicily, and southern extremity of India. In calculating latitudes of climata (latitudes correlated with the length of the longest solstitial day), Hipparchus used an unexpectedly accurate value for the obliquity of the ecliptic, 23°40' (the actual value in the second half of the 2nd century BC was approximately 23°43'), whereas all other ancient authors knew only a roughly rounded value 24°, and even Ptolemy used a less accurate value, 23°51'.

Hipparchus opposed the view generally accepted in the Hellenistic period that the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and the Caspian Sea are parts of a single ocean. At the same time he extends the limits of the oikoumene, i.e. the inhabited part of the land, up to the equator and the Arctic Circle. Hipparchus' ideas found their reflection in the Geography of Ptolemy. In essence, Ptolemy's work is an extended attempt to realize Hipparchus' vision of what geography ought to be.

Modern speculation

Hipparchus was in the international news in 2005, when it was again proposed (as in 1898) that the data on the celestial globe of Hipparchus or in his star catalog may have been preserved in the only surviving large ancient celestial globe which depicts the constellations with moderate accuracy, the globe carried by the Farnese Atlas. There are a variety of mis-steps in the more ambitious 2005 paper, thus no specialists in the area accept its widely publicized speculation. Actually, it has been even shown that the Farnese globe shows constellations in the Aratean tradition and deviates from the constellations in mathematical astronomy that is used by Hipparchus.

Lucio Russo has said that Plutarch, in his work On the Face in the Moon, was reporting some physical theories that we consider to be Newtonian and that these may have come originally from Hipparchus; he goes on to say that Newton may have been influenced by them. According to one book review, both of these claims have been rejected by other scholars.

A line in Plutarch's Table Talk states that Hipparchus counted 103,049 compound propositions that can be formed from ten simple propositions. 103,049 is the tenth Schröder–Hipparchus number, which counts the number of ways of adding one or more pairs of parentheses around consecutive subsequences of two or more items in any sequence of ten symbols. This has led to speculation that Hipparchus knew about enumerative combinatorics, a field of mathematics that developed independently in modern mathematics.

Legacy

He may be depicted opposite Ptolemy in Raphael's 1509–1511 painting The School of Athens, although this figure is usually identified as Zoroaster.

The formal name for the ESA's Hipparcos Space Astrometry Mission was High Precision Parallax Collecting Satellite; making a backronym, HiPParCoS, that echoes and commemorates the name of Hipparchus.

The lunar crater Hipparchus and the asteroid 4000 Hipparchus are named after him.

He was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 2004.

Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre, historian of astronomy, mathematical astronomer and director of the Paris Observatory, in his history of astronomy in the 18th century (1821), considered Hipparchus along with Johannes Kepler and James Bradley the greatest astronomers of all time.

The Astronomers Monument at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, California, United States features a relief of Hipparchus as one of six of the greatest astronomers of all time and the only one from Antiquity.

Johannes Kepler had great respect for Tycho Brahe's methods and the accuracy of his observations, and considered him to be the new Hipparchus, who would provide the foundation for a restoration of the science of astronomy.