A watch is a portable timepiece intended to be carried or worn by a person. It is designed to keep a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is designed to be worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or other type of bracelet, including metal bands, leather straps, or any other kind of bracelet. A pocket watch is designed for a person to carry in a pocket, often attached to a chain.

Watches were developed in the 17th century from spring-powered clocks, which appeared as early as the 14th century. During most of its history the watch was a mechanical device, driven by clockwork, powered by winding a mainspring, and keeping time with an oscillating balance wheel. These are called mechanical watches. In the 1960s the electronic quartz watch was invented, which was powered by a battery and kept time with a vibrating quartz crystal. By the 1980s the quartz watch had taken over most of the market from the mechanical watch. Historically, this is called the quartz revolution (also known as quartz crisis in Switzerland). Developments in the 2010s include smart watches, which are elaborate computer-like electronic devices designed to be worn on a wrist. They generally incorporate timekeeping functions, but these are only a small subset of the smartwatch's facilities.

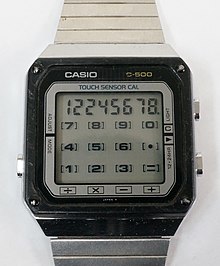

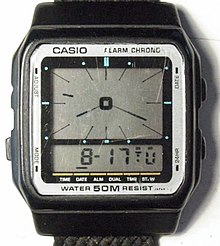

In general, modern watches often display the day, date, month, and year. For mechanical watches, various extra features called "complications", such as moon-phase displays and the different types of tourbillon, are sometimes included. Most electronic quartz watches, on the other hand, include time-related features such as timers, chronographs and alarm functions. Furthermore, some modern watches (like smart watches) even incorporate calculators, GPS and Bluetooth technology or have heart-rate monitoring capabilities, and some of them use radio clock technology to regularly correct the time.

Most watches that are used mainly for timekeeping have quartz movements. However, expensive collectible watches, valued more for their elaborate craftsmanship, aesthetic appeal, and glamorous design than for simple timekeeping, often have traditional mechanical movements, despite being less accurate and more expensive than their electronic counterparts. As of 2018, the most expensive watch ever sold at auction was the Patek Philippe Henry Graves Supercomplication, the world's most complicated mechanical watch until 1989, fetching US$24 million (CHF 23,237,000) in Geneva on 11 November 2014. As of December 2019, the most expensive watch ever sold at auction (and wristwatch) was the Patek Philippe Grandmaster Chime Ref. 6300A-010, fetching US$31.19 million (CHF 31,000,000) in Geneva on 9 November 2019.

History

Origins

Watches evolved from portable spring-driven clocks, which first appeared in 15th-century Europe. The first timepieces to be worn, made in the 16th century beginning in the German cities of Nuremberg and Augsburg, were transitional in size between clocks and watches. Nuremberg clockmaker Peter Henlein (or Henle or Hele) (1485–1542) is often credited as the inventor of the watch. However, other German clockmakers were creating miniature timepieces during this period, and there is no evidence Henlein was the first.

Watches were not widely worn in pockets until the 17th century. One account suggests that the word "watch" came from the Old English word woecce – which meant "watchman" – because town watchmen used the technology to keep track of their shifts at work. Another says that the term came from 17th-century sailors, who used the new mechanisms to time the length of their shipboard watches (duty shifts).

Evolution

A rise in accuracy occurred in 1657 with the addition of the balance spring to the balance wheel, an invention disputed both at the time and ever since between Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens. This innovation increased watches' accuracy enormously, reducing error from perhaps several hours per day to perhaps 10 minutes per day, resulting in the addition of the minute hand to the face from around 1680 in Britain and around 1700 in France.

The increased accuracy of the balance wheel focused attention on errors caused by other parts of the movement, igniting a two-century wave of watchmaking innovation. The first thing to be improved was the escapement. The verge escapement was replaced in quality watches by the cylinder escapement, invented by Thomas Tompion in 1695 and further developed by George Graham in the 1720s. Improvements in manufacturing – such as the tooth-cutting machine devised by Robert Hooke – allowed some increase in the volume of watch production, although finishing and assembling was still done by hand until well into the 19th century.

A major cause of error in balance-wheel timepieces, caused by changes in elasticity of the balance spring from temperature changes, was solved by the bimetallic temperature-compensated balance wheel invented in 1765 by Pierre Le Roy and improved by Thomas Earnshaw (1749–1829). The lever escapement, the single most important technological breakthrough, though invented by Thomas Mudge in 1759 and improved by Josiah Emery in 1785, only gradually came into use from about 1800 onwards, chiefly in Britain.

The British predominated in watch manufacture for much of the 17th and 18th centuries, but maintained a system of production that was geared towards high-quality products for the élite. The British Watch Company modernized clock manufacture with mass-production techniques and the application of duplicating tools and machinery in 1843. In the United States, Aaron Lufkin Dennison started a factory in 1851 in Massachusetts that used interchangeable parts, and by 1861 a successful enterprise operated, incorporated as the Waltham Watch Company.

Wristwatches

The concept of the wristwatch goes back to the production of the very earliest watches in the 16th century. In 1571 Elizabeth I of England received a wristwatch, described as an "armed watch", from Robert Dudley. The oldest surviving wristwatch (then described as a "bracelet watch") is one made in 1806 and given to Joséphine de Beauharnais. From the beginning, wristwatches were almost exclusively worn by women – men used pocket watches up until the early-20th century. In 1810, the watch-maker Abraham-Louis Breguet made a wristwatch for the Queen of Naples. The first Swiss wristwatch was made by the Swiss watch-maker Patek Philippe, in the year 1868 for Countess Koscowicz of Hungary.

Wristwatches were first worn by military men towards the end of the 19th century, having increasingly recognized the importance of synchronizing maneuvers during war without potentially revealing plans to the enemy through signaling. The Garstin Company of London patented a "Watch Wristlet" design in 1893, but probably produced similar designs from the 1880s. Officers in the British Army began using wristwatches during colonial military campaigns in the 1880s, such as during the Anglo-Burma War of 1885. During the First Boer War of 1880–1881 the importance of coordinating troop movements and synchronizing attacks against highly mobile Boer insurgents became paramount, and the use of wristwatches subsequently became widespread among the officer class. The company Mappin & Webb began production of their successful "campaign watch" for soldiers during the campaign in the Sudan in 1898 and accelerated production for the Second Boer War of 1899–1902 a few years later. In continental Europe, Girard-Perregaux and other Swiss watchmakers began supplying German naval officers with wristwatches in about 1880.

Early models were essentially standard pocket-watches fitted to a leather strap, but by the early 20th century, manufacturers began producing purpose-built wristwatches. The Swiss company Dimier Frères & Cie patented a wristwatch design with the now standard wire lugs in 1903.

In 1904, Louis Cartier produced a wristwatch to allow his friend Alberto Santos-Dumont to check flight performance in his airship while keeping both hands on the controls as this proved difficult with a pocket watch. Cartier still markets a line of Santos-Dumont watches and sunglasses.

In 1905, Hans Wilsdorf moved to London and set up his own business, Wilsdorf & Davis, with his brother-in-law Alfred Davis, providing quality timepieces at affordable prices; the company became Rolex in 1915. Wilsdorf was an early convert to the wristwatch, and contracted the Swiss firm Aegler to produce a line of wristwatches.

The impact of the First World War of 1914–1918 dramatically shifted public perceptions on the propriety of the man's wristwatch and opened up a mass market in the postwar era. The creeping barrage artillery tactic, developed during the war, required precise synchronization between the artillery gunners and the infantry advancing behind the barrage. Service watches produced during the war were specially designed for the rigors of trench warfare, with luminous dials and unbreakable glass. The War Office began issuing wristwatches to combatants from 1917. By the end of the war, almost all enlisted men wore a wristwatch (or wristlet), and after they were demobilized the fashion soon caught on: the British Horological Journal wrote in 1917 that "the wristlet watch was little used by the sterner sex before the war, but now is seen on the wrist of nearly every man in uniform and of many men in civilian attire." By 1930, the wristwatch vastly exceeded the pocket watch in market share by a decisive ratio of 50:1.

Automatic watches

John Harwood invented the first successful self-winding system in 1923. In anticipation of Harwood's patent for self-winding mechanisms expiration in 1930, Glycine founder Eugène Meylan started development on a self-winding system as a separate module that could be used with almost any 8.75 ligne (19.74 millimeter) watch movement. Glycine incorporated this module into its watches in October 1930 and began mass-producing automatic watches.

Electric watches

The Elgin National Watch Company and the Hamilton Watch Company pioneered the first electric watch. The first electric movements used a battery as a power source to oscillate the balance wheel. During the 1950s Elgin developed the model 725 while Hamilton released two models: the first, the Hamilton 500, released on 3 January 1957, was produced into 1959. This model had problems with the contact wires misaligning, and the watches returned to Hamilton for alignment. The Hamilton 505, an improvement on the 500, proved more reliable: the contact wires were removed and a non-adjustable contact on the balance assembly delivered the power to the balance wheel. Similar designs from many other watch companies followed. Another type of electric watch was developed by the Bulova company that used a tuning-fork resonator instead of a traditional balance wheel to increase timekeeping accuracy, moving from a typical 2.5–4 Hz with a traditional balance wheel to 360 Hz with the tuning-fork design.

Quartz watches

The commercial introduction of the quartz watch in 1969 in the form of the Seiko Astron 35SQ and in 1970 in the form of the Omega Beta 21 was a revolutionary improvement in watch technology. In place of a balance wheel which oscillated at perhaps 5 or 6 beats per second, these devices used a quartz-crystal resonator which vibrated at 8,192 Hz, driven by a battery-powered oscillator circuit. Most quartz-watch oscillators now operate at 32,768 Hz, although quartz movements have been designed with frequencies as high as 262 kHz. Since the 1980s, more quartz watches than mechanical ones have been marketed.

Parts

The movement and case are the basic parts of a watch. A watch band or bracelet is added to form a wristwatch; alternatively, a watch chain is added to form a pocket watch.

The case is the outer covering of the watch.

The case back is the back portion of the watch's case. Accessing the movement (such as during battery replacement) depends on the type of case back, which are generally categorized into four types:

- Snap-off case backs (press-on case backs): the watch back pulls straight off and presses straight on.

- Screw-down case backs (threaded case backs): the entire watch back must be rotated to unscrew from the case. Often it has 6 notches on the external part of the case back.

- Screw back cases: tiny screws hold the case back to the case

- Unibody: the only way into the case involves prying the crystal off the front of the watch.

The crystal, also called the window or watch glass, is the transparent part of the case that allows viewing the hands and the dial of the movement. Modern wristwatches almost always use one of 4 materials:

- Acrylic glass (plexiglass, hesalite glass): the most impact-resistant ("unbreakable"), and therefore used in dive watches and most military watches. Acrylic glass is the lowest cost of these materials, so it is used in practically all low-cost watches.

- Mineral crystal: a tempered glass.

- Sapphire-coated mineral crystal

- Synthetic sapphire crystal: the most scratch-resistant; it is difficult to cut and polish, causing watch crystals made of sapphire to be the most expensive.

The bezel is the ring holding the crystal in place.

The lugs are small metal projections at both ends of the wristwatch case where the watch band attaches to the watch case. The case and the lugs are often machined from one solid piece of stainless steel.

Movement

The movement of a watch is the mechanism that measures the passage of time and displays the current time (and possibly other information including date, month, and day). Movements may be entirely mechanical, entirely electronic (potentially with no moving parts), or they might be a blend of both. Most watches intended mainly for timekeeping today have electronic movements, with mechanical hands on the watch face indicating the time.

Mechanical

Compared to electronic movements, mechanical watches are less accurate, often with errors of seconds per day; are sensitive to position, temperature, and magnetism; are costly to produce; require regular maintenance and adjustments; and are more prone to failures. Nevertheless, mechanical watches attract interest from consumers, particularly among watch collectors. Skeleton watches are designed to display the mechanism for aesthetic purposes.

A mechanical movement uses an escapement mechanism to control and limit the unwinding and winding parts of a spring, converting what would otherwise be a simple unwinding into a controlled and periodic energy release. The movement also uses a balance wheel, together with the balance spring (also known as a hairspring), to control the gear system's motion in a manner analogous to the pendulum of a pendulum clock. The tourbillon, an optional part for mechanical movements, is a rotating frame for the escapement, used to cancel out or reduce gravitational bias. Due to the complexity of designing a tourbillon, they are expensive, and typically found in prestigious watches.

The pin-lever escapement (called the Roskopf movement after its inventor, Georges Frederic Roskopf), which is a cheaper version of the fully levered movement, was manufactured in huge quantities by many Swiss manufacturers, as well as by Timex, until it was replaced by quartz movements.

Introduced by Bulova in 1960, tuning-fork watches use a type of electromechanical movement with a precise frequency (most often 360 Hz) to drive a mechanical watch. The task of converting electronically pulsed fork vibration into rotary movements is done via two tiny jeweled fingers, called pawls. Tuning-fork watches were rendered obsolete when electronic quartz watches were developed.

Traditional mechanical watch movements use a spiral spring called a mainspring as its power source that must be rewound periodically by the user by turning the watch crown. Antique pocket watches were wound by inserting a key into the back of the watch and turning it. While most modern watches are designed to run 40 hours on a winding, requiring winding daily, some run for several days; a few have 192-hour mainsprings, requiring once-weekly winding.

Automatic watches

A self-winding or automatic watch is one that rewinds the mainspring of a mechanical movement by the natural motions of the wearer's body. The first self-winding mechanism was invented for pocket watches in 1770 by Abraham-Louis Perrelet, but the first "self-winding", or "automatic", wristwatch was the invention of a British watch repairer named John Harwood in 1923. This type of watch winds itself without requiring any special action by the wearer. It uses an eccentric weight, called a winding rotor, which rotates with the movement of the wearer's wrist. The back-and-forth motion of the winding rotor couples to a ratchet to wind the mainspring automatically. Self-winding watches usually can also be wound manually to keep them running when not worn or if the wearer's wrist motions are inadequate to keep the watch wound.

In April 2014 the Swatch Group launched the sistem51 wristwatch. It has a purely mechanical movement consisting of only 51 parts, including a novel self-winding mechanism with a transparent oscillating weight. So far, it is the only mechanical movement manufactured entirely on a fully automated assembly line. The low parts count and the automated assembly make it an inexpensive mechanical Swiss watch, which can be considered a successor to Roskopf movements, although of higher quality.

Electronic

Electronic movements, also known as quartz movements, have few or no moving parts, except a quartz crystal which is made to vibrate by the piezoelectric effect. A varying electric voltage is applied to the crystal, which responds by changing its shape so, in combination with some electronic components, it functions as an oscillator. It resonates at a specific highly stable frequency, which is used to accurately pace a timekeeping mechanism. Most quartz movements are primarily electronic but are geared to drive mechanical hands on the face of the watch to provide a traditional analog display of the time, a feature most consumers still prefer.

In 1959 Seiko placed an order with Epson (a subsidiary company of Seiko and the 'brain' behind the quartz revolution) to start developing a quartz wristwatch. The project was codenamed 59A. By the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics, Seiko had a working prototype of a portable quartz watch which was used as the time measurements throughout the event.

The first prototypes of an electronic quartz wristwatch (not just portable quartz watches as the Seiko timekeeping devices at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964) were made by the CEH research laboratory in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. From 1965 through 1967 pioneering development work was done on a miniaturized 8192 Hz quartz oscillator, a thermo-compensation module, and an in-house-made, dedicated integrated circuit (unlike the hybrid circuits used in the later Seiko Astron wristwatch). As a result, the BETA 1 prototype set new timekeeping performance records at the International Chronometric Competition held at the Observatory of Neuchâtel in 1967. In 1970, 18 manufacturers exhibited production versions of the beta 21 wristwatch, including the Omega Electroquartz as well as Patek Philippe, Rolex Oysterquartz and Piaget.

The first quartz watch to enter production was the Seiko 35 SQ Astron, which hit the shelves on 25 December 1969, swiftly followed by the Swiss Beta 21, and then a year later the prototype of one of the world's most accurate wristwatches to date: the Omega Marine Chronometer. Since the technology having been developed by contributions from Japanese, American and Swiss, nobody could patent the whole movement of the quartz wristwatch, thus allowing other manufacturers to participate in the rapid growth and development of the quartz watch market. This ended – in less than a decade – almost 100 years of dominance by the mechanical wristwatch legacy. Modern quartz movements are produced in very large quantities, and even the cheapest wristwatches typically have quartz movements. Whereas mechanical movements can typically be off by several seconds a day, an inexpensive quartz movement in a child's wristwatch may still be accurate to within half a second per day – ten times more accurate than a mechanical movement.

After a consolidation of the mechanical watch industry in Switzerland during the 1970s, mass production of quartz wristwatches took off under the leadership of the Swatch Group of companies, a Swiss conglomerate with vertical control of the production of Swiss watches and related products. For quartz wristwatches, subsidiaries of Swatch manufacture watch batteries (Renata), oscillators (Oscilloquartz, now Micro Crystal AG) and integrated circuits (Ebauches Electronic SA, renamed EM Microelectronic-Marin). The launch of the new SWATCH brand in 1983 was marked by bold new styling, design, and marketing. Today, the Swatch Group maintains its position as the world's largest watch company.

Seiko's efforts to combine the quartz and mechanical movements bore fruit after 20 years of research, leading to the introduction of the Seiko Spring Drive, first in a limited domestic market production in 1999 and to the world in September 2005. The Spring Drive keeps time within quartz standards without the use of a battery, using a traditional mechanical gear train powered by a spring, without the need for a balance wheel either.

In 2010, Miyota (Citizen Watch) of Japan introduced a newly developed movement that uses a 3-pronged quartz crystal that was exclusively produced for Bulova to be used in the Precisionist or Accutron II line, a new type of quartz watch with ultra-high frequency (262.144 kHz) which is claimed to be accurate to +/− 10 seconds a year and has a smooth sweeping second hand rather than one that jumps each second.

Radio time signal watches are a type of electronic quartz watch that synchronizes (time transfers) its time with an external time source such as in atomic clocks, time signals from GPS navigation satellites, the German DCF77 signal in Europe, WWVB in the US, and others. Movements of this type may, among others, synchronize the time of day and the date, the leap-year status and the state of daylight saving time (on or off). However, other than the radio receiver, these watches are normal quartz watches in all other aspects.

Electronic watches require electricity as a power source, and some mechanical movements and hybrid electronic-mechanical movements also require electricity. Usually, the electricity is provided by a replaceable battery. The first use of electrical power in watches was as a substitute for the mainspring, to remove the need for winding. The first electrically powered watch, the Hamilton Electric 500, was released in 1957 by the Hamilton Watch Company of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Watch batteries (strictly speaking cells, as a battery is composed of multiple cells) are specially designed for their purpose. They are very small and provide tiny amounts of power continuously for very long periods (several years or more). In most cases, replacing the battery requires a trip to a watch-repair shop or watch dealer; this is especially true for watches that are water-resistant, as special tools and procedures are required for the watch to remain water-resistant after battery replacement. Silver-oxide and lithium batteries are popular today; mercury batteries, formerly quite common, are no longer used, for environmental reasons. Cheap batteries may be alkaline, of the same size as silver-oxide cells but providing shorter life. Rechargeable batteries are used in some solar-powered watches.

Some electronic watches are powered by the movement of the wearer. For instance, Seiko's kinetic-powered quartz watches use the motion of the wearer's arm: turning a rotating weight which causes a tiny generator to supply power to charge a rechargeable battery that runs the watch. The concept is similar to that of self-winding spring movements, except that electrical power is generated instead of mechanical spring tension.

Solar powered watches are powered by light. A photovoltaic cell on the face (dial) of the watch converts light to electricity, which is used to charge a rechargeable battery or capacitor. The movement of the watch draws its power from the rechargeable battery or capacitor. As long as the watch is regularly exposed to fairly strong light (such as sunlight), it never needs a battery replacement. Some models need only a few minutes of sunlight to provide weeks of energy (as in the Citizen Eco-Drive). Some of the early solar watches of the 1970s had innovative and unique designs to accommodate the array of solar cells needed to power them (Synchronar, Nepro, Sicura, and some models by Cristalonic, Alba, Seiko, and Citizen). As the decades progressed and the efficiency of the solar cells increased while the power requirements of the movement and display decreased, solar watches began to be designed to look like other conventional watches.

A rarely used power source is the temperature difference between the wearer's arm and the surrounding environment (as applied in the Citizen Eco-Drive Thermo).

Display

Analog

Traditionally, watches have displayed the time in analog form, with a numbered dial upon which are mounted at least a rotating hour hand and a longer, rotating minute hand. Many watches also incorporate a third hand that shows the current second of the current minute. In quartz watches this second hand typically snaps to the next marker every second. In mechanical watches, the second hand may appear to glide continuously, though in fact it merely moves in smaller steps, typically one-fifth to one-tenth of a second, corresponding to the beat (half period) of the balance wheel. With a duplex escapement, the hand advances every two beats (full period) of the balance wheel, typically 1⁄2-second; this happens every four beats (two periods, 1 second), with a double duplex escapement. A truly gliding second hand is achieved with the tri-synchro regulator of Spring Drive watches. All three hands are normally mechanical, physically rotating on the dial, although a few watches have been produced with "hands" simulated by a liquid-crystal display.

Analog display of the time is nearly universal in watches sold as jewelry or collectibles, and in these watches, the range of different styles of hands, numbers, and other aspects of the analog dial is very broad. In watches sold for timekeeping, analog display remains very popular, as many people find it easier to read than digital display; but in timekeeping watches the emphasis is on clarity and accurate reading of the time under all conditions (clearly marked digits, easily visible hands, large watch faces, etc.). They are specifically designed for the left wrist with the stem (the knob used for changing the time) on the right side of the watch; this makes it easy to change the time without removing the watch from the wrist. This is the case if one is right-handed and the watch is worn on the left wrist (as is traditionally done). If one is left-handed and wears the watch on the right wrist, one has to remove the watch from the wrist to reset the time or to wind the watch.

Analog watches, as well as clocks, are often marketed showing a display time of approximately 1:50 or 10:10. This creates a visually pleasing smile-like face on the upper half of the watch, in addition to enclosing the manufacturer's name. Digital displays often show a time of 12:08, where the increase in the number of active segments or pixels gives a positive feeling.

Tactile

Tissot, a Swiss luxury watchmaker, makes the Silen-T wristwatch with a touch-sensitive face that vibrates to help the user to tell time eyes-free. The bezel of the watch features raised bumps at each hour mark; after briefly touching the face of the watch, the wearer runs a finger around the bezel clockwise. When the finger reaches the bump indicating the hour, the watch vibrates continuously, and when the finger reaches the bump indicating the minute, the watch vibrates intermittently.

Eone Timepieces, a Washington D.C.-based company, launched its first tactile analog wristwatch, the "Bradley", on 11 July 2013 on the Kickstarter website. The device is primarily designed for sight-impaired users, who can use the watch's two ball bearings to determine the time, but it is also suitable for general use. The watch features raised marks at each hour and two moving, magnetically attached ball bearings. One ball bearing, on the edge of the watch, indicates the hour, while the other, on the face, indicates the minute.

Digital

A digital display shows the time as a number, e.g., 12:08 instead of a shorthand pointing towards the number 12 and a long hand 8/60 of the way around the dial. The digits are usually shown as a seven-segment display.

The first digital mechanical pocket watches appeared in the late 19th century. In the 1920s, the first digital mechanical wristwatches appeared.

The first digital electronic watch, a Pulsar LED prototype in 1970, was developed jointly by Hamilton Watch Company and Electro-Data, founded by George H. Thiess. John Bergey, the head of Hamilton's Pulsar division, said that he was inspired to make a digital timepiece by the then-futuristic digital clock that Hamilton themselves made for the 1968 science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey. On 4 April 1972, the Pulsar was finally ready, made in an 18-carat gold case and sold for $2,100. It had a red light-emitting diode (LED) display.

Digital LED watches were very expensive and out of reach to the common consumer until 1975, when Texas Instruments started to mass-produce LED watches inside a plastic case. These watches, which first retailed for only $20, reduced to $10 in 1976, saw Pulsar lose $6 million and the Pulsar brand sold to Seiko.

An early LED watch that was rather problematic was The Black Watch made and sold by British company Sinclair Radionics in 1975. This was only sold for a few years, as production problems and returned (faulty) product forced the company to cease production.

Most watches with LED displays required that the user press a button to see the time displayed for a few seconds because LEDs used so much power that they could not be kept operating continuously. Usually, the LED display color would be red. Watches with LED displays were popular for a few years, but soon the LED displays were superseded by liquid crystal displays (LCDs), which used less battery power and were much more convenient in use, with the display always visible and eliminating the need to push a button before seeing the time. Only in darkness would a button needed to be pressed to illuminate the display with a tiny light bulb, later illuminating LEDs and electroluminescent backlights.

The first LCD watch with a six-digit LCD was the 1973 Seiko 06LC, although various forms of early LCD watches with a four-digit display were marketed as early as 1972 including the 1972 Gruen Teletime LCD Watch, and the Cox Electronic Systems Quarza. The Quarza, introduced in 1972 had the first Field Effect LCD readable in direct sunlight and produced by the International Liquid Crystal Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio. In Switzerland, Ebauches Electronic SA presented a prototype eight-digit LCD wristwatch showing time and date at the MUBA Fair, Basle, in March 1973, using a twisted nematic LCD manufactured by Brown, Boveri & Cie, Switzerland, which became the supplier of LCDs to Casio for the CASIOTRON watch in 1974.

A problem with LCDs is that they use polarized light. If, for example, the user is wearing polarized sunglasses, the watch may be difficult to read because the plane of polarization of the display is roughly perpendicular to that of the glasses. If the light that illuminates the display is polarized, for example if it comes from a blue sky, the display may be difficult or impossible to read.

From the 1980s onward, digital watch technology vastly improved. In 1982, Seiko produced the Seiko TV Watch that had a television screen built-in, and Casio produced a digital watch with a thermometer (the TS-1000) as well as another that could translate 1,500 Japanese words into English. In 1985, Casio produced the CFX-400 scientific calculator watch. In 1987, Casio produced a watch that could dial telephone numbers (the DBA-800) and Citizen introduced one that would react to voice. In 1995, Timex released a watch that allowed the wearer to download and store data from a computer to their wrist. Some watches, such as the Timex Datalink USB, feature dot matrix displays. Since their apex during the late 1980s to mid-1990s high technology fad, digital watches have mostly become simpler, less expensive timepieces with little variety between models.

-

Cortébert digital mechanical pocket watch (1890s)

-

Cortébert digital mechanical wristwatch (1920s)

-

A Timex digital watch with an always-on display of the time and date

-

A Digital LCD watch with electroluminescent backlight.

-

Samsung Galaxy Watch series smartwatches with OLED displays.

Illuminated

Many watches have displays that are illuminated, so they can be used in darkness. Various methods have been used to achieve this.

Mechanical watches often have luminous paint on their hands and hour marks. In the mid-20th century, radioactive material was often incorporated in the paint, so it would continue to glow without any exposure to light. Radium was often used but produced small amounts of radiation outside the watch that might have been hazardous. Tritium was used as a replacement, since the radiation it produces has such low energy that it cannot penetrate a watch glass. However, tritium is expensive – it has to be made in a nuclear reactor – and it has a half-life of only about 12 years so the paint remains luminous for only a few years. Nowadays, tritium is used in specialized watches, e.g., for military purposes (see Tritium illumination). For other purposes, luminous paint is sometimes used on analog displays, but no radioactive material is contained in it. This means that the display glows soon after being exposed to light and quickly fades.

Watches that incorporate batteries often have electric illumination in their displays. However, lights consume far more power than electronic watch movements. To conserve the battery, the light is activated only when the user presses a button. Usually, the light remains lit for a few seconds after the button is released, which allows the user to move the hand out of the way.

In some early digital watches, LED displays were used, which could be read as easily in darkness as in daylight. The user had to press a button to light up the LEDs, which meant that the watch could not be read without the button being pressed, even in full daylight.

In some types of watches, small incandescent lamps or LEDs illuminate the display, which is not intrinsically luminous. These tend to produce very non-uniform illumination.

Other watches use electroluminescent material to produce uniform illumination of the background of the display, against which the hands or digits can be seen.

Speech synthesis

Talking watches are available, intended for the blind or visually impaired. They speak the time out loud at the press of a button. This has the disadvantage of disturbing others nearby or at least alerting the non-deaf that the wearer is checking the time. Tactile watches are preferred to avoid this awkwardness, but talking watches are preferred for those who are not confident in their ability to read a tactile watch reliably.

Handedness

Wristwatches with analog displays generally have a small knob, called the crown, that can be used to adjust the time and, in mechanical watches, wind the spring. Almost always, the crown is located on the right-hand side of the watch so it can be worn of the left wrist for a right-handed individual. This makes it inconvenient to use if the watch is being worn on the right wrist. Some manufacturers offer "left-hand drive", aka "destro", configured watches which move the crown to the left side making wearing the watch easier for left-handed individuals.

A rarer configuration is the bullhead watch. Bullhead watches are generally, but not exclusively, chronographs. The configuration moves the crown and chronograph pushers to the top of the watch. Bullheads are commonly wristwatch chronographs that are intended to be used as stopwatches off the wrist. Examples are the Citizen Bullhead Change Timer and the Omega Seamaster Bullhead.

Digital watches generally have push-buttons that can be used to make adjustments. These are usually equally easy to use on either wrist.

Functions

Customarily, watches provide the time of day, giving at least the hour and minute, and often the second. Many also provide the current date, and some (called "complete calendar" or "triple date" watches) display the day of the week and the month as well. However, many watches also provide a great deal of information beyond the basics of time and date. Some watches include alarms. Other elaborate and more expensive watches, both pocket and wrist models, also incorporate striking mechanisms or repeater functions, so that the wearer could learn the time by the sound emanating from the watch. This announcement or striking feature is an essential characteristic of true clocks and distinguishes such watches from ordinary timepieces. This feature is available on most digital watches.

A complicated watch has one or more functions beyond the basic function of displaying the time and the date; such a functionality is called a complication. Two popular complications are the chronograph complication, which is the ability of the watch movement to function as a stopwatch, and the moonphase complication, which is a display of the lunar phase. Other more expensive complications include Tourbillon, Perpetual calendar, Minute repeater, and Equation of time. A truly complicated watch has many of these complications at once (see Calibre 89 from Patek Philippe for instance). Some watches can both indicate the direction of Mecca and have alarms that can be set for all daily prayer requirements. Among watch enthusiasts, complicated watches are especially collectible. Some watches include a second 12-hour or 24-hour display for UTC or GMT.

The similar-sounding terms chronograph and chronometer are often confused, although they mean altogether different things. A chronograph is a watch with an added duration timer, often a stopwatch complication (as explained above), while a chronometer watch is a timepiece that has met an industry-standard test for performance under pre-defined conditions: a chronometer is a high quality mechanical or a thermo-compensated movement that has been tested and certified to operate within a certain standard of accuracy by the COSC (Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres). The concepts are different but not mutually exclusive; so a watch can be a chronograph, a chronometer, both, or neither.

Electronic sports watches, combining timekeeping with GPS and/or activity tracking, address the general fitness market and have the potential for commercial success (Garmin Forerunner, Garmin Vivofit, Epson, announced model of Swatch Touch series).

Braille watches have analog displays with raised bumps around the face to allow blind users to tell the time. Their digital equivalents use synthesised speech to speak the time on command.

Fashion

Wristwatches and antique pocket watches are often appreciated as jewelry or as collectible works of art rather than just as timepieces. This has created several different markets for wristwatches, ranging from very inexpensive but accurate watches (intended for no other purpose than telling the correct time) to extremely expensive watches that serve mainly as personal adornment or as examples of high achievement in miniaturization and precision mechanical engineering.

Traditionally, dress watches appropriate for informal (business), semi-formal, and formal attire are gold, thin, simple, and plain, but increasingly rugged, complicated, or sports watches are considered by some to be acceptable for such attire. Some dress watches have a cabochon on the crown or faceted gemstones on the face, bezel, or bracelet. Some are made entirely of faceted sapphire (corundum).

Many fashions and department stores offer a variety of less-expensive, trendy, "costume" watches (usually for women), many of which are similar in quality to basic quartz timepieces but which feature bolder designs. In the 1980s, the Swiss Swatch company hired graphic designers to redesign a new annual collection of non-repairable watches.

Trade in counterfeit watches, which mimic expensive brand-name watches, constitutes an estimated US$1 billion market per year.

Space

The zero-gravity environment and other extreme conditions encountered by astronauts in space require the use of specially tested watches.

The first-ever watch to be sent into space was a Russian "Pobeda" watch from the Petrodvorets Watch Factory. It was sent on a single orbit flight on the spaceship Korabl-Sputnik 4 on 9 March 1961. The watch had been attached without authorisation to the wrist of Chernuchka, a dog that successfully did exactly the same trip as Yuri Gagarin, with exactly the same rocket and equipment, just a month before Gagarin's flight.

On 12 April 1961, Gagarin wore a Shturmanskie (a transliteration of Штурманские which actually means "navigator's") wristwatch during his historic first flight into space. The Shturmanskie was manufactured at the First Moscow Factory. Since 1964, the watches of the First Moscow Factory have been marked by the trademark "Полёт", transliterated as "POLJOT", which means "flight" in Russian and is a tribute to the many space trips its watches have accomplished. In the late 1970s, Poljot launched a new chrono movement, the 3133. With a 23 jewel movement and manual winding (43 hours), it was a modified Russian version of the Swiss Valjoux 7734 of the early 1970s. Poljot 3133 were taken into space by astronauts from Russia, France, Germany and Ukraine. On the arm of Valeriy Polyakov, a Poljot 3133 chronograph movement-based watch set a space record for the longest space flight in history.

Through the 1960s, a large range of watches was tested for durability and precision under extreme temperature changes and vibrations. The Omega Speedmaster Professional was selected by NASA, the U.S. space agency, and it is mostly known thanks to astronaut Buzz Aldrin who wore it during the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon landing. Heuer became the first Swiss watch in space thanks to a Heuer Stopwatch, worn by John Glenn in 1962 when he piloted the Friendship 7 on the first crewed U.S. orbital mission. The Breitling Navitimer Cosmonaute was designed with a 24-hour analog dial to avoid confusion between AM and PM, which are meaningless in space. It was first worn in space by U.S. astronaut Scott Carpenter on 24 May 1962 in the Aurora 7 Mercury capsule.

Since 1994 Fortis is the exclusive supplier for crewed space missions authorized by the Russian Federal Space Agency. China National Space Administration (CNSA) astronauts wear the Fiyta spacewatches. At BaselWorld, 2008, Seiko announced the creation of the first watch ever designed specifically for a space walk, Spring Drive Spacewalk. Timex Datalink is flight certified by NASA for space missions and is one of the watches qualified by NASA for space travel. The Casio G-Shock DW-5600C and 5600E, DW 6900, and DW 5900 are Flight-Qualified for NASA space travel.

Various Timex Datalink models were used both by cosmonauts and astronauts.

Scuba diving

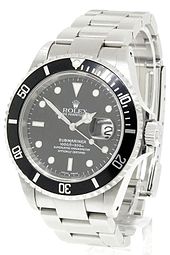

Watch construction may be water-resistant. These watches are sometimes called diving watches when they are suitable for scuba diving or saturation diving. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) issued a standard for water-resistant watches which also prohibits the term "waterproof" to be used with watches, which many countries have adopted. In the United States, advertising a watch as waterproof has been illegal since 1968, per Federal Trade Commission regulations regarding the "misrepresentation of protective features".

Water-resistance is achieved by the gaskets which forms a watertight seal, used in conjunction with a sealant applied on the case to help keep water out. The material of the case must also be tested in order to pass as water-resistant.

None of the tests defined by ISO 2281 for the Water Resistant mark are suitable to qualify a watch for scuba diving. Such watches are designed for everyday life and must be water-resistant during exercises such as swimming. They can be worn in different temperature and pressure conditions but are under no circumstances designed for scuba diving.

The standards for diving watches are regulated by the ISO 6425 international standard. The watches are tested in static or still water under 125% of the rated (water) pressure, thus a watch with a 200-metre rating will be water-resistant if it is stationary and under 250 metres of static water. The testing of the water-resistance is fundamentally different from non-dive watches, because every watch has to be fully tested. Besides water resistance standards to a minimum of 100-metre depth rating, ISO 6425 also provides eight minimum requirements for mechanical diver's watches for scuba diving (quartz and digital watches have slightly differing readability requirements). For diver's watches for mixed-gas saturation diving two additional ISO 6425 requirements have to be met.

Watches are classified by their degree of water resistance, which roughly translates to the following (1 metre = 3.281 feet):

| Water-resistance rating | Suitability | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Water Resistant or 30 m | Suitable for everyday use. Splash/rain resistant. | Not suitable for diving, swimming, snorkeling, water-related work, or fishing. |

| Water Resistant 50 m | Suitable for swimming, white-water rafting, non-snorkeling water related work, and fishing. | Not suitable for diving. |

| Water Resistant 100 m | Suitable for recreational surfing, swimming, snorkeling, sailing, and water sports. | Not suitable for diving. |

| Water Resistant 200 m | Suitable for professional marine activity and serious surface water sports. | Suitable for diving. |

| Diver's 100 m | Minimum ISO standard for scuba diving at depths not requiring helium gas. | Diver's 100 m and 150 m watches are generally old(er) watches. |

| Diver's 200 m or 300 m | Suitable for scuba diving at depths not requiring helium gas. | Typical ratings for contemporary diver's watches. |

| Diver's 300+ m helium safe | Suitable for saturation diving (helium-enriched environment). | Watches designed for helium mixed-gas diving will have additional markings to indicate this. |

Some watches use bar instead of meters, which may then be multiplied by 10, and then subtract 10 to be approximately equal to the rating based on metres. Therefore, a 5 bar watch is equivalent to a 40-metre watch. Some watches are rated in atmospheres (atm), which are roughly equivalent to bar.

There is a traditional method by which an analog watch can be used to locate north and south. The Sun appears to move in the sky over a 24-hour period while the hour hand of a 12-hour clock face takes twelve hours to complete one rotation. In the northern hemisphere, if the watch is rotated so that the hour hand points toward the Sun, the point halfway between the hour hand and 12 o'clock will indicate south. For this method to work in the southern hemisphere, the 12 is pointed toward the Sun and the point halfway between the hour hand and 12 o'clock will indicate north. During daylight saving time, the same method can be employed using 1 o'clock instead of 12. This method is accurate enough to be used only at fairly high latitudes.

![{\displaystyle I(\Delta L)\sim [1+\gamma (\Delta L)\cos(2k\Delta L)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cccdfd2322867179c4f04092d9ce3c4379383f7a)

![{\displaystyle I(\Delta L)\sim [1+[\gamma (\Delta L)+0.25]\cos(\Delta k\Delta L)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5cb51b7c5eb788de0df9bc91130b2e1d0deaad6)