Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultimate purpose and meaning of science as a human endeavour. Philosophy of science focuses on metaphysical, epistemic and semantic aspects of scientific practice, and overlaps with metaphysics, ontology, logic, and epistemology, for example, when it explores the relationship between science and the concept of truth. Philosophy of science is both a theoretical and empirical discipline, relying on philosophical theorising as well as meta-studies of scientific practice. Ethical issues such as bioethics and scientific misconduct are often considered ethics or science studies rather than the philosophy of science.

Many of the central problems concerned with the philosophy of science lack contemporary consensus, including whether science can infer truth about unobservable entities and whether inductive reasoning can be justified as yielding definite scientific knowledge. Philosophers of science also consider philosophical problems within particular sciences (such as biology, physics and social sciences such as economics and psychology). Some philosophers of science also use contemporary results in science to reach conclusions about philosophy itself.

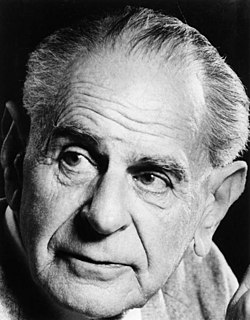

While philosophical thought pertaining to science dates back at least to the time of Aristotle, the general philosophy of science emerged as a distinct discipline only in the 20th century following the logical positivist movement, which aimed to formulate criteria for ensuring all philosophical statements' meaningfulness and objectively assessing them. Karl Popper criticized logical positivism and helped establish a modern set of standards for scientific methodology. Thomas Kuhn's 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was also formative, challenging the view of scientific progress as the steady, cumulative acquisition of knowledge based on a fixed method of systematic experimentation and instead arguing that any progress is relative to a "paradigm", the set of questions, concepts, and practices that define a scientific discipline in a particular historical period.

Subsequently, the coherentist approach to science, in which a theory is validated if it makes sense of observations as part of a coherent whole, became prominent due to W. V. Quine and others. Some thinkers such as Stephen Jay Gould seek to ground science in axiomatic assumptions, such as the uniformity of nature. A vocal minority of philosophers, and Paul Feyerabend in particular, argue against the existence of the "scientific method", so all approaches to science should be allowed, including explicitly supernatural ones. Another approach to thinking about science involves studying how knowledge is created from a sociological perspective, an approach represented by scholars like David Bloor and Barry Barnes. Finally, a tradition in continental philosophy approaches science from the perspective of a rigorous analysis of human experience.

Philosophies of the particular sciences range from questions about the nature of time raised by Einstein's general relativity, to the implications of economics for public policy. A central theme is whether the terms of one scientific theory can be intra- or intertheoretically reduced to the terms of another. Can chemistry be reduced to physics, or can sociology be reduced to individual psychology? The general questions of philosophy of science also arise with greater specificity in some particular sciences. For instance, the question of the validity of scientific reasoning is seen in a different guise in the foundations of statistics. The question of what counts as science and what should be excluded arises as a life-or-death matter in the philosophy of medicine. Additionally, the philosophies of biology, psychology, and the social sciences explore whether the scientific studies of human nature can achieve objectivity or are inevitably shaped by values and by social relations.

Introduction

Defining science

Distinguishing between science and non-science is referred to as the demarcation problem. For example, should psychoanalysis, creation science, and historical materialism be considered pseudosciences? Karl Popper called this the central question in the philosophy of science. However, no unified account of the problem has won acceptance among philosophers, and some regard the problem as unsolvable or uninteresting. Martin Gardner has argued for the use of a Potter Stewart standard ("I know it when I see it") for recognizing pseudoscience.

Early attempts by the logical positivists grounded science in observation while non-science was non-observational and hence meaningless. Popper argued that the central property of science is falsifiability. That is, every genuinely scientific claim is capable of being proven false, at least in principle.

An area of study or speculation that masquerades as science in an attempt to claim a legitimacy that it would not otherwise be able to achieve is referred to as pseudoscience, fringe science, or junk science. Physicist Richard Feynman coined the term "cargo cult science" for cases in which researchers believe they are doing science because their activities have the outward appearance of it but actually lack the "kind of utter honesty" that allows their results to be rigorously evaluated.

Scientific explanation

A closely related question is what counts as a good scientific explanation. In addition to providing predictions about future events, society often takes scientific theories to provide explanations for events that occur regularly or have already occurred. Philosophers have investigated the criteria by which a scientific theory can be said to have successfully explained a phenomenon, as well as what it means to say a scientific theory has explanatory power.

One early and influential account of scientific explanation is the deductive-nomological model. It says that a successful scientific explanation must deduce the occurrence of the phenomena in question from a scientific law. This view has been subjected to substantial criticism, resulting in several widely acknowledged counterexamples to the theory. It is especially challenging to characterize what is meant by an explanation when the thing to be explained cannot be deduced from any law because it is a matter of chance, or otherwise cannot be perfectly predicted from what is known. Wesley Salmon developed a model in which a good scientific explanation must be statistically relevant to the outcome to be explained. Others have argued that the key to a good explanation is unifying disparate phenomena or providing a causal mechanism.

Justifying science

Although it is often taken for granted, it is not at all clear how one can infer the validity of a general statement from a number of specific instances or infer the truth of a theory from a series of successful tests. For example, a chicken observes that each morning the farmer comes and gives it food, for hundreds of days in a row. The chicken may therefore use inductive reasoning to infer that the farmer will bring food every morning. However, one morning, the farmer comes and kills the chicken. How is scientific reasoning more trustworthy than the chicken's reasoning?

One approach is to acknowledge that induction cannot achieve certainty, but observing more instances of a general statement can at least make the general statement more probable. So the chicken would be right to conclude from all those mornings that it is likely the farmer will come with food again the next morning, even if it cannot be certain. However, there remain difficult questions about the process of interpreting any given evidence into a probability that the general statement is true. One way out of these particular difficulties is to declare that all beliefs about scientific theories are subjective, or personal, and correct reasoning is merely about how evidence should change one's subjective beliefs over time.

Some argue that what scientists do is not inductive reasoning at all but rather abductive reasoning, or inference to the best explanation. In this account, science is not about generalizing specific instances but rather about hypothesizing explanations for what is observed. As discussed in the previous section, it is not always clear what is meant by the "best explanation". Occam's razor, which counsels choosing the simplest available explanation, thus plays an important role in some versions of this approach. To return to the example of the chicken, would it be simpler to suppose that the farmer cares about it and will continue taking care of it indefinitely or that the farmer is fattening it up for slaughter? Philosophers have tried to make this heuristic principle more precise regarding theoretical parsimony or other measures. Yet, although various measures of simplicity have been brought forward as potential candidates, it is generally accepted that there is no such thing as a theory-independent measure of simplicity. In other words, there appear to be as many different measures of simplicity as there are theories themselves, and the task of choosing between measures of simplicity appears to be every bit as problematic as the job of choosing between theories. Nicholas Maxwell has argued for some decades that unity rather than simplicity is the key non-empirical factor in influencing the choice of theory in science, persistent preference for unified theories in effect committing science to the acceptance of a metaphysical thesis concerning unity in nature. In order to improve this problematic thesis, it needs to be represented in the form of a hierarchy of theses, each thesis becoming more insubstantial as one goes up the hierarchy.

Observation inseparable from theory

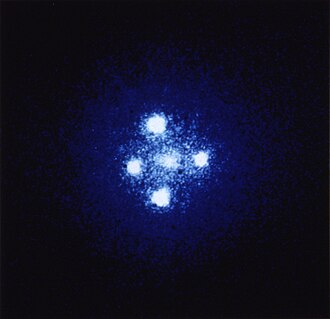

When making observations, scientists look through telescopes, study images on electronic screens, record meter readings, and so on. Generally, on a basic level, they can agree on what they see, e.g., the thermometer shows 37.9 degrees C. But, if these scientists have different ideas about the theories that have been developed to explain these basic observations, they may disagree about what they are observing. For example, before Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, observers would have likely interpreted an image of the Einstein cross as five different objects in space. In light of that theory, however, astronomers will tell you that there are actually only two objects, one in the center and four different images of a second object around the sides. Alternatively, if other scientists suspect that something is wrong with the telescope and only one object is actually being observed, they are operating under yet another theory. Observations that cannot be separated from theoretical interpretation are said to be theory-laden.

All observation involves both perception and cognition. That is, one does not make an observation passively, but rather is actively engaged in distinguishing the phenomenon being observed from surrounding sensory data. Therefore, observations are affected by one's underlying understanding of the way in which the world functions, and that understanding may influence what is perceived, noticed, or deemed worthy of consideration. In this sense, it can be argued that all observation is theory-laden.

The purpose of science

Should science aim to determine ultimate truth, or are there questions that science cannot answer? Scientific realists claim that science aims at truth and that one ought to regard scientific theories as true, approximately true, or likely true. Conversely, scientific anti-realists argue that science does not aim (or at least does not succeed) at truth, especially truth about unobservables like electrons or other universes. Instrumentalists argue that scientific theories should only be evaluated on whether they are useful. In their view, whether theories are true or not is beside the point, because the purpose of science is to make predictions and enable effective technology.

Realists often point to the success of recent scientific theories as evidence for the truth (or near truth) of current theories. Antirealists point to either the many false theories in the history of science, epistemic morals, the success of false modeling assumptions, or widely termed postmodern criticisms of objectivity as evidence against scientific realism. Antirealists attempt to explain the success of scientific theories without reference to truth. Some antirealists claim that scientific theories aim at being accurate only about observable objects and argue that their success is primarily judged by that criterion.

Real patterns

The notion of real patterns has been propounded, notably by philosopher Daniel C. Dennett, as an intermediate position between strong realism and eliminative materialism. This concept delves into the investigation of patterns observed in scientific phenomena to ascertain whether they signify underlying truths or are mere constructs of human interpretation. Dennett provides a unique ontological account concerning real patterns, examining the extent to which these recognized patterns have predictive utility and allow for efficient compression of information.

The discourse on real patterns extends beyond philosophical circles, finding relevance in various scientific domains. For example, in biology, inquiries into real patterns seek to elucidate the nature of biological explanations, exploring how recognized patterns contribute to a comprehensive understanding of biological phenomena. Similarly, in chemistry, debates around the reality of chemical bonds as real patterns continue.

Evaluation of real patterns also holds significance in broader scientific inquiries. Researchers, like Tyler Millhouse, propose criteria for evaluating the realness of a pattern, particularly in the context of universal patterns and the human propensity to perceive patterns, even where there might be none. This evaluation is pivotal in advancing research in diverse fields, from climate change to machine learning, where recognition and validation of real patterns in scientific models play a crucial role.

Values and science

Values intersect with science in different ways. There are epistemic values that mainly guide the scientific research. The scientific enterprise is embedded in particular culture and values through individual practitioners. Values emerge from science, both as product and process and can be distributed among several cultures in the society. When it comes to the justification of science in the sense of general public participation by single practitioners, science plays the role of a mediator between evaluating the standards and policies of society and its participating individuals, wherefore science indeed falls victim to vandalism and sabotage adapting the means to the end.

If it is unclear what counts as science, how the process of confirming theories works, and what the purpose of science is, there is considerable scope for values and other social influences to shape science. Indeed, values can play a role ranging from determining which research gets funded to influencing which theories achieve scientific consensus. For example, in the 19th century, cultural values held by scientists about race shaped research on evolution, and values concerning social class influenced debates on phrenology (considered scientific at the time). Feminist philosophers of science, sociologists of science, and others explore how social values affect science.

History

Pre-modern

The origins of philosophy of science trace back to Plato and Aristotle, who distinguished the forms of approximate and exact reasoning, set out the threefold scheme of abductive, deductive, and inductive inference, and also analyzed reasoning by analogy. The eleventh century Arab polymath Ibn al-Haytham (known in Latin as Alhazen) conducted his research in optics by way of controlled experimental testing and applied geometry, especially in his investigations into the images resulting from the reflection and refraction of light. Roger Bacon (1214–1294), an English thinker and experimenter heavily influenced by al-Haytham, is recognized by many to be the father of modern scientific method. His view that mathematics was essential to a correct understanding of natural philosophy is considered to have been 400 years ahead of its time.

Modern

Francis Bacon (no direct relation to Roger Bacon, who lived 300 years earlier) was a seminal figure in philosophy of science at the time of the Scientific Revolution. In his work Novum Organum (1620)—an allusion to Aristotle's Organon—Bacon outlined a new system of logic to improve upon the old philosophical process of syllogism. Bacon's method relied on experimental histories to eliminate alternative theories. In 1637, René Descartes established a new framework for grounding scientific knowledge in his treatise, Discourse on Method, advocating the central role of reason as opposed to sensory experience. By contrast, in 1713, the 2nd edition of Isaac Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica argued that "... hypotheses ... have no place in experimental philosophy. In this philosophy[,] propositions are deduced from the phenomena and rendered general by induction." This passage influenced a "later generation of philosophically-inclined readers to pronounce a ban on causal hypotheses in natural philosophy". In particular, later in the 18th century, David Hume would famously articulate skepticism about the ability of science to determine causality and gave a definitive formulation of the problem of induction, though both theses would be contested by the end of the 18th century by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason and Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. In 19th century Auguste Comte made a major contribution to the theory of science. The 19th century writings of John Stuart Mill are also considered important in the formation of current conceptions of the scientific method, as well as anticipating later accounts of scientific explanation.

Logical positivism

Instrumentalism became popular among physicists around the turn of the 20th century, after which logical positivism defined the field for several decades. Logical positivism accepts only testable statements as meaningful, rejects metaphysical interpretations, and embraces verificationism (a set of theories of knowledge that combines logicism, empiricism, and linguistics to ground philosophy on a basis consistent with examples from the empirical sciences). Seeking to overhaul all of philosophy and convert it to a new scientific philosophy, the Berlin Circle and the Vienna Circle propounded logical positivism in the late 1920s.

Interpreting Ludwig Wittgenstein's early philosophy of language, logical positivists identified a verifiability principle or criterion of cognitive meaningfulness. From Bertrand Russell's logicism they sought reduction of mathematics to logic. They also embraced Russell's logical atomism, Ernst Mach's phenomenalism—whereby the mind knows only actual or potential sensory experience, which is the content of all sciences, whether physics or psychology—and Percy Bridgman's operationalism. Thereby, only the verifiable was scientific and cognitively meaningful, whereas the unverifiable was unscientific, cognitively meaningless "pseudostatements"—metaphysical, emotive, or such—not worthy of further review by philosophers, who were newly tasked to organize knowledge rather than develop new knowledge.

Logical positivism is commonly portrayed as taking the extreme position that scientific language should never refer to anything unobservable—even the seemingly core notions of causality, mechanism, and principles—but that is an exaggeration. Talk of such unobservables could be allowed as metaphorical—direct observations viewed in the abstract—or at worst metaphysical or emotional. Theoretical laws would be reduced to empirical laws, while theoretical terms would garner meaning from observational terms via correspondence rules. Mathematics in physics would reduce to symbolic logic via logicism, while rational reconstruction would convert ordinary language into standardized equivalents, all networked and united by a logical syntax. A scientific theory would be stated with its method of verification, whereby a logical calculus or empirical operation could verify its falsity or truth.

In the late 1930s, logical positivists fled Germany and Austria for Britain and America. By then, many had replaced Mach's phenomenalism with Otto Neurath's physicalism, and Rudolf Carnap had sought to replace verification with simply confirmation. With World War II's close in 1945, logical positivism became milder, logical empiricism, led largely by Carl Hempel, in America, who expounded the covering law model of scientific explanation as a way of identifying the logical form of explanations without any reference to the suspect notion of "causation". The logical positivist movement became a major underpinning of analytic philosophy, and dominated Anglosphere philosophy, including philosophy of science, while influencing sciences, into the 1960s. Yet the movement failed to resolve its central problems, and its doctrines were increasingly assaulted. Nevertheless, it brought about the establishment of philosophy of science as a distinct subdiscipline of philosophy, with Carl Hempel playing a key role.

Thomas Kuhn

In the 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn argued that the process of observation and evaluation takes place within a "paradigm", which he describes as "universally recognized achievements that for a time provide model problems and solutions to community of practitioners." A paradigm implicitly identifies the objects and relations under study and suggests what experiments, observations or theoretical improvements need to be carried out to produce a useful result. He characterized normal science as the process of observation and "puzzle solving" which takes place within a paradigm, whereas revolutionary science occurs when one paradigm overtakes another in a paradigm shift.

Kurn was a historian of science, and his ideas were inspired by the study of older paradigms that have been discarded, such as Aristotelian mechanics or aether theory. These had often been portrayed by historians as using "unscientific" methods or beliefs. But careful examination showed that they were no less "scientific" than modern paradigms. Both were based on valid evidence, both failed to answer every possible question.

A paradigm shift occurred when a significant number of observational anomalies arose in the old paradigm and efforts to resolve them within the paradigm were unsuccessful. A new paradigm was available that handled the anomalies with less difficulty and yet still covered (most of) the previous results. Over a period of time, often as long as a generation, more practitioners began working within the new paradigm and eventually the old paradigm was abandoned. For Kuhn, acceptance or rejection of a paradigm is a social process as much as a logical process.

Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism; he wrote "terms like 'subjective' and 'intuitive' cannot be applied to [paradigms]." Paradigms are grounded in objective, observable evidence, but our use of them is psychological and our acceptance of them is social.

Current approaches

Naturalism's axiomatic assumptions

According to Robert Priddy, all scientific study inescapably builds on at least some essential assumptions that cannot be tested by scientific processes; that is, that scientists must start with some assumptions as to the ultimate analysis of the facts with which it deals. These assumptions would then be justified partly by their adherence to the types of occurrence of which we are directly conscious, and partly by their success in representing the observed facts with a certain generality, devoid of ad hoc suppositions." Kuhn also claims that all science is based on assumptions about the character of the universe, rather than merely on empirical facts. These assumptions – a paradigm – comprise a collection of beliefs, values and techniques that are held by a given scientific community, which legitimize their systems and set the limitations to their investigation. For naturalists, nature is the only reality, the "correct" paradigm, and there is no such thing as supernatural, i.e. anything above, beyond, or outside of nature. The scientific method is to be used to investigate all reality, including the human spirit.

Some claim that naturalism is the implicit philosophy of working scientists, and that the following basic assumptions are needed to justify the scientific method:

- That there is an objective reality shared by all rational observers. "The basis for rationality is acceptance of an external objective reality." "Objective reality is clearly an essential thing if we are to develop a meaningful perspective of the world. Nevertheless its very existence is assumed." "Our belief that objective reality exist is an assumption that it arises from a real world outside of ourselves. As infants we made this assumption unconsciously. People are happy to make this assumption that adds meaning to our sensations and feelings, than live with solipsism." "Without this assumption, there would be only the thoughts and images in our own mind (which would be the only existing mind) and there would be no need of science, or anything else."

- That this objective reality is governed by natural laws;

"Science, at least today, assumes that the universe obeys knowable principles that don't depend on time or place, nor on subjective parameters such as what we think, know or how we behave." Hugh Gauch argues that science presupposes that "the physical world is orderly and comprehensible." - That reality can be discovered by means of systematic observation and experimentation.

Stanley Sobottka said: "The assumption of external reality is necessary for science to function and to flourish. For the most part, science is the discovering and explaining of the external world." "Science attempts to produce knowledge that is as universal and objective as possible within the realm of human understanding." - That Nature has uniformity of laws and most if not all things in nature must have at least a natural cause.

Biologist Stephen Jay Gould referred to these two closely related propositions as the constancy of nature's laws and the operation of known processes. Simpson agrees that the axiom of uniformity of law, an unprovable postulate, is necessary in order for scientists to extrapolate inductive inference into the unobservable past in order to meaningfully study it. "The assumption of spatial and temporal invariance of natural laws is by no means unique to geology since it amounts to a warrant for inductive inference which, as Bacon showed nearly four hundred years ago, is the basic mode of reasoning in empirical science. Without assuming this spatial and temporal invariance, we have no basis for extrapolating from the known to the unknown and, therefore, no way of reaching general conclusions from a finite number of observations. (Since the assumption is itself vindicated by induction, it can in no way "prove" the validity of induction — an endeavor virtually abandoned after Hume demonstrated its futility two centuries ago)." Gould also notes that natural processes such as Lyell's "uniformity of process" are an assumption: "As such, it is another a priori assumption shared by all scientists and not a statement about the empirical world." According to R. Hooykaas: "The principle of uniformity is not a law, not a rule established after comparison of facts, but a principle, preceding the observation of facts ... It is the logical principle of parsimony of causes and of economy of scientific notions. By explaining past changes by analogy with present phenomena, a limit is set to conjecture, for there is only one way in which two things are equal, but there are an infinity of ways in which they could be supposed different." - That experimental procedures will be done satisfactorily without any deliberate or unintentional mistakes that will influence the results.

- That experimenters won't be significantly biased by their presumptions.

- That random sampling is representative of the entire population.

A simple random sample (SRS) is the most basic probabilistic option used for creating a sample from a population. The benefit of SRS is that the investigator is guaranteed to choose a sample that represents the population that ensures statistically valid conclusions.

Coherentism

In contrast to the view that science rests on foundational assumptions, coherentism asserts that statements are justified by being a part of a coherent system. Or, rather, individual statements cannot be validated on their own: only coherent systems can be justified. A prediction of a transit of Venus is justified by its being coherent with broader beliefs about celestial mechanics and earlier observations. As explained above, observation is a cognitive act. That is, it relies on a pre-existing understanding, a systematic set of beliefs. An observation of a transit of Venus requires a huge range of auxiliary beliefs, such as those that describe the optics of telescopes, the mechanics of the telescope mount, and an understanding of celestial mechanics. If the prediction fails and a transit is not observed, that is likely to occasion an adjustment in the system, a change in some auxiliary assumption, rather than a rejection of the theoretical system.

According to the Duhem–Quine thesis, after Pierre Duhem and W.V. Quine, it is impossible to test a theory in isolation. One must always add auxiliary hypotheses in order to make testable predictions. For example, to test Newton's Law of Gravitation in the solar system, one needs information about the masses and positions of the Sun and all the planets. Famously, the failure to predict the orbit of Uranus in the 19th century led not to the rejection of Newton's Law but rather to the rejection of the hypothesis that the Solar System comprises only seven planets. The investigations that followed led to the discovery of an eighth planet, Neptune. If a test fails, something is wrong. But there is a problem in figuring out what that something is: a missing planet, badly calibrated test equipment, an unsuspected curvature of space, or something else.

One consequence of the Duhem–Quine thesis is that one can make any theory compatible with any empirical observation by the addition of a sufficient number of suitable ad hoc hypotheses. Karl Popper accepted this thesis, leading him to reject naïve falsification. Instead, he favored a "survival of the fittest" view in which the most falsifiable scientific theories are to be preferred.

Anything goes methodology

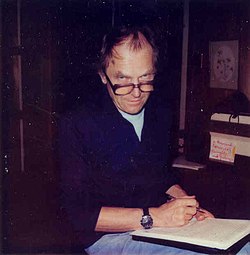

Paul Feyerabend (1924–1994) argued that no description of scientific method could possibly be broad enough to include all the approaches and methods used by scientists, and that there are no useful and exception-free methodological rules governing the progress of science. He argued that "the only principle that does not inhibit progress is: anything goes".

Feyerabend said that science started as a liberating movement, but that over time it had become increasingly dogmatic and rigid and had some oppressive features, and thus had become increasingly an ideology. Because of this, he said it was impossible to come up with an unambiguous way to distinguish science from religion, magic, or mythology. He saw the exclusive dominance of science as a means of directing society as authoritarian and ungrounded. Promulgation of this epistemological anarchism earned Feyerabend the title of "the worst enemy of science" from his detractors.

Sociology of scientific knowledge methodology

According to Kuhn, science is an inherently communal activity which can only be done as part of a community. For him, the fundamental difference between science and other disciplines is the way in which the communities function. Others, especially Feyerabend and some post-modernist thinkers, have argued that there is insufficient difference between social practices in science and other disciplines to maintain this distinction. For them, social factors play an important and direct role in scientific method, but they do not serve to differentiate science from other disciplines. On this account, science is socially constructed, though this does not necessarily imply the more radical notion that reality itself is a social construct.

Michel Foucault sought to analyze and uncover how disciplines within the social sciences developed and adopted the methodologies used by their practitioners. In works like The Archaeology of Knowledge, he used the term human sciences. The human sciences do not comprise mainstream academic disciplines; they are rather an interdisciplinary space for the reflection on man who is the subject of more mainstream scientific knowledge, taken now as an object, sitting between these more conventional areas, and of course associating with disciplines such as anthropology, psychology, sociology, and even history. Rejecting the realist view of scientific inquiry, Foucault argued throughout his work that scientific discourse is not simply an objective study of phenomena, as both natural and social scientists like to believe, but is rather the product of systems of power relations struggling to construct scientific disciplines and knowledge within given societies. With the advances of scientific disciplines, such as psychology and anthropology, the need to separate, categorize, normalize and institutionalize populations into constructed social identities became a staple of the sciences. Constructions of what were considered "normal" and "abnormal" stigmatized and ostracized groups of people, like the mentally ill and sexual and gender minorities.

However, some (such as Quine) do maintain that scientific reality is a social construct:

Physical objects are conceptually imported into the situation as convenient intermediaries not by definition in terms of experience, but simply as irreducible posits comparable, epistemologically, to the gods of Homer ... For my part I do, qua lay physicist, believe in physical objects and not in Homer's gods; and I consider it a scientific error to believe otherwise. But in point of epistemological footing, the physical objects and the gods differ only in degree and not in kind. Both sorts of entities enter our conceptions only as cultural posits.

The public backlash of scientists against such views, particularly in the 1990s, became known as the science wars.

A major development in recent decades has been the study of the formation, structure, and evolution of scientific communities by sociologists and anthropologists – including David Bloor, Harry Collins, Bruno Latour, Ian Hacking and Anselm Strauss. Concepts and methods (such as rational choice, social choice or game theory) from economics have also been applied for understanding the efficiency of scientific communities in the production of knowledge. This interdisciplinary field has come to be known as science and technology studies. Here the approach to the philosophy of science is to study how scientific communities actually operate.

Continental philosophy

Philosophers in the continental philosophical tradition are not traditionally categorized as philosophers of science. However, they have much to say about science, some of which has anticipated themes in the analytical tradition. For example, in The Genealogy of Morals (1887) Friedrich Nietzsche advanced the thesis that the motive for the search for truth in sciences is a kind of ascetic ideal.

In general, continental philosophy views science from a world-historical perspective. Philosophers such as Pierre Duhem (1861–1916) and Gaston Bachelard (1884–1962) wrote their works with this world-historical approach to science, predating Kuhn's 1962 work by a generation or more. All of these approaches involve a historical and sociological turn to science, with a priority on lived experience (a kind of Husserlian "life-world"), rather than a progress-based or anti-historical approach as emphasised in the analytic tradition. One can trace this continental strand of thought through the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), the late works of Merleau-Ponty (Nature: Course Notes from the Collège de France, 1956–1960), and the hermeneutics of Martin Heidegger (1889–1976).

The largest effect on the continental tradition with respect to science came from Martin Heidegger's critique of the theoretical attitude in general, which of course includes the scientific attitude. For this reason, the continental tradition has remained much more skeptical of the importance of science in human life and in philosophical inquiry. Nonetheless, there have been a number of important works: especially those of a Kuhnian precursor, Alexandre Koyré (1892–1964). Another important development was that of Michel Foucault's analysis of historical and scientific thought in The Order of Things (1966) and his study of power and corruption within the "science" of madness. Post-Heideggerian authors contributing to continental philosophy of science in the second half of the 20th century include Jürgen Habermas (e.g., Truth and Justification, 1998), Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker (The Unity of Nature, 1980; German: Die Einheit der Natur (1971)), and Wolfgang Stegmüller (Probleme und Resultate der Wissenschaftstheorie und Analytischen Philosophie, 1973–1986).

Other topics

Reductionism

Analysis involves breaking an observation or theory down into simpler concepts in order to understand it. Reductionism can refer to one of several philosophical positions related to this approach. One type of reductionism suggests that phenomena are amenable to scientific explanation at lower levels of analysis and inquiry. Perhaps a historical event might be explained in sociological and psychological terms, which in turn might be described in terms of human physiology, which in turn might be described in terms of chemistry and physics. Daniel Dennett distinguishes legitimate reductionism from what he calls greedy reductionism, which denies real complexities and leaps too quickly to sweeping generalizations.

Social accountability

A broad issue affecting the neutrality of science concerns the areas which science chooses to explore—that is, what part of the world and of humankind are studied by science. Philip Kitcher in his Science, Truth, and Democracy argues that scientific studies that attempt to show one segment of the population as being less intelligent, less successful, or emotionally backward compared to others have a political feedback effect which further excludes such groups from access to science. Thus such studies undermine the broad consensus required for good science by excluding certain people, and so proving themselves in the end to be unscientific.

Philosophy of particular sciences

There is no such thing as philosophy-free science; there is only science whose philosophical baggage is taken on board without examination.

— Daniel Dennett, Darwin's Dangerous Idea, 1995

In addition to addressing the general questions regarding science and induction, many philosophers of science are occupied by investigating foundational problems in particular sciences. They also examine the implications of particular sciences for broader philosophical questions. The late 20th and early 21st century has seen a rise in the number of practitioners of philosophy of a particular science.

Philosophy of statistics

The problem of induction discussed above is seen in another form in debates over the foundations of statistics. The standard approach to statistical hypothesis testing avoids claims about whether evidence supports a hypothesis or makes it more probable. Instead, the typical test yields a p-value, which is the probability of the evidence being such as it is, under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. If the p-value is too high, the hypothesis is rejected, in a way analogous to falsification. In contrast, Bayesian inference seeks to assign probabilities to hypotheses. Related topics in philosophy of statistics include probability interpretations, overfitting, and the difference between correlation and causation.

Philosophy of mathematics

Philosophy of mathematics is concerned with the philosophical foundations and implications of mathematics. The central questions are whether numbers, triangles, and other mathematical entities exist independently of the human mind and what is the nature of mathematical propositions. Is asking whether "1 + 1 = 2" is true fundamentally different from asking whether a ball is red? Was calculus invented or discovered? A related question is whether learning mathematics requires experience or reason alone. What does it mean to prove a mathematical theorem and how does one know whether a mathematical proof is correct? Philosophers of mathematics also aim to clarify the relationships between mathematics and logic, human capabilities such as intuition, and the material universe.

Philosophy of physics

Philosophy of physics is the study of the fundamental, philosophical questions underlying modern physics, the study of matter and energy and how they interact. The main questions concern the nature of space and time, atoms and atomism. Also included are the predictions of cosmology, the interpretation of quantum mechanics, the foundations of statistical mechanics, causality, determinism, and the nature of physical laws. Classically, several of these questions were studied as part of metaphysics (for example, those about causality, determinism, and space and time).

Philosophy of chemistry

Philosophy of chemistry is the philosophical study of the methodology and content of the science of chemistry. It is explored by philosophers, chemists, and philosopher-chemist teams. It includes research on general philosophy of science issues as applied to chemistry. For example, can all chemical phenomena be explained by quantum mechanics or is it not possible to reduce chemistry to physics? For another example, chemists have discussed the philosophy of how theories are confirmed in the context of confirming reaction mechanisms. Determining reaction mechanisms is difficult because they cannot be observed directly. Chemists can use a number of indirect measures as evidence to rule out certain mechanisms, but they are often unsure if the remaining mechanism is correct because there are many other possible mechanisms that they have not tested or even thought of. Philosophers have also sought to clarify the meaning of chemical concepts which do not refer to specific physical entities, such as chemical bonds.

Philosophy of astronomy

The philosophy of astronomy seeks to understand and analyze the methodologies and technologies used by experts in the discipline, focusing on how observations made about space and astrophysical phenomena can be studied. Given that astronomers rely and use theories and formulas from other scientific disciplines, such as chemistry and physics, the pursuit of understanding how knowledge can be obtained about the cosmos, as well as the relation in which Earth and the Solar System have within personal views of humanity's place in the universe, philosophical insights into how facts about space can be scientifically analyzed and configure with other established knowledge is a main point of inquiry.

Philosophy of Earth sciences

The philosophy of Earth science is concerned with how humans obtain and verify knowledge of the workings of the Earth system, including the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere (solid earth). Earth scientists' ways of knowing and habits of mind share important commonalities with other sciences, but also have distinctive attributes that emerge from the complex, heterogeneous, unique, long-lived, and non-manipulatable nature of the Earth system.

Philosophy of biology

Philosophy of biology deals with epistemological, metaphysical, and ethical issues in the biological and biomedical sciences. Although philosophers of science and philosophers generally have long been interested in biology (e.g., Aristotle, Descartes, Leibniz and even Kant), philosophy of biology only emerged as an independent field of philosophy in the 1960s and 1970s. Philosophers of science began to pay increasing attention to developments in biology, from the rise of the modern synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s to the discovery of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in 1953 to more recent advances in genetic engineering. Other key ideas such as the reduction of all life processes to biochemical reactions as well as the incorporation of psychology into a broader neuroscience are also addressed. Research in current philosophy of biology includes investigation of the foundations of evolutionary theory (such as Peter Godfrey-Smith's work), and the role of viruses as persistent symbionts in host genomes. As a consequence, the evolution of genetic content order is seen as the result of competent genome editors in contrast to former narratives in which error replication events (mutations) dominated.

Philosophy of medicine

Beyond medical ethics and bioethics, the philosophy of medicine is a branch of philosophy that includes the epistemology and ontology/metaphysics of medicine. Within the epistemology of medicine, evidence-based medicine (EBM) (or evidence-based practice (EBP)) has attracted attention, most notably the roles of randomisation, blinding and placebo controls. Related to these areas of investigation, ontologies of specific interest to the philosophy of medicine include Cartesian dualism, the monogenetic conception of disease and the conceptualization of 'placebos' and 'placebo effects'. There is also a growing interest in the metaphysics of medicine, particularly the idea of causation. Philosophers of medicine might not only be interested in how medical knowledge is generated, but also in the nature of such phenomena. Causation is of interest because the purpose of much medical research is to establish causal relationships, e.g. what causes disease, or what causes people to get better.

Philosophy of psychiatry

Philosophy of psychiatry explores philosophical questions relating to psychiatry and mental illness. The philosopher of science and medicine Dominic Murphy identifies three areas of exploration in the philosophy of psychiatry. The first concerns the examination of psychiatry as a science, using the tools of the philosophy of science more broadly. The second entails the examination of the concepts employed in discussion of mental illness, including the experience of mental illness, and the normative questions it raises. The third area concerns the links and discontinuities between the philosophy of mind and psychopathology.

Philosophy of psychology

Philosophy of psychology refers to issues at the theoretical foundations of modern psychology. Some of these issues are epistemological concerns about the methodology of psychological investigation. For example, is the best method for studying psychology to focus only on the response of behavior to external stimuli or should psychologists focus on mental perception and thought processes? If the latter, an important question is how the internal experiences of others can be measured. Self-reports of feelings and beliefs may not be reliable because, even in cases in which there is no apparent incentive for subjects to intentionally deceive in their answers, self-deception or selective memory may affect their responses. Then even in the case of accurate self-reports, how can responses be compared across individuals? Even if two individuals respond with the same answer on a Likert scale, they may be experiencing very different things.

Other issues in philosophy of psychology are philosophical questions about the nature of mind, brain, and cognition, and are perhaps more commonly thought of as part of cognitive science, or philosophy of mind. For example, are humans rational creatures? Is there any sense in which they have free will, and how does that relate to the experience of making choices? Philosophy of psychology also closely monitors contemporary work conducted in cognitive neuroscience, psycholinguistics, and artificial intelligence, questioning what they can and cannot explain in psychology.

Philosophy of psychology is a relatively young field, because psychology only became a discipline of its own in the late 1800s. In particular, neurophilosophy has just recently become its own field with the works of Paul Churchland and Patricia Churchland. Philosophy of mind, by contrast, has been a well-established discipline since before psychology was a field of study at all. It is concerned with questions about the very nature of mind, the qualities of experience, and particular issues like the debate between dualism and monism.

Philosophy of social science

The philosophy of social science is the study of the logic and method of the social sciences, such as sociology and cultural anthropology. Philosophers of social science are concerned with the differences and similarities between the social and the natural sciences, causal relationships between social phenomena, the possible existence of social laws, and the ontological significance of structure and agency.

The French philosopher, Auguste Comte (1798–1857), established the epistemological perspective of positivism in The Course in Positivist Philosophy, a series of texts published between 1830 and 1842. The first three volumes of the Course dealt chiefly with the natural sciences already in existence (geoscience, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology), whereas the latter two emphasised the inevitable coming of social science: "sociologie". For Comte, the natural sciences had to necessarily arrive first, before humanity could adequately channel its efforts into the most challenging and complex "Queen science" of human society itself. Comte offers an evolutionary system proposing that society undergoes three phases in its quest for the truth according to a general 'law of three stages'. These are (1) the theological, (2) the metaphysical, and (3) the positive.

Comte's positivism established the initial philosophical foundations for formal sociology and social research. Durkheim, Marx, and Weber are more typically cited as the fathers of contemporary social science. In psychology, a positivistic approach has historically been favoured in behaviourism. Positivism has also been espoused by 'technocrats' who believe in the inevitability of social progress through science and technology.

The positivist perspective has been associated with 'scientism'; the view that the methods of the natural sciences may be applied to all areas of investigation, be it philosophical, social scientific, or otherwise. Among most social scientists and historians, orthodox positivism has long since lost popular support. Today, practitioners of both social and physical sciences instead take into account the distorting effect of observer bias and structural limitations. This scepticism has been facilitated by a general weakening of deductivist accounts of science by philosophers such as Thomas Kuhn, and new philosophical movements such as critical realism and neopragmatism. The philosopher-sociologist Jürgen Habermas has critiqued pure instrumental rationality as meaning that scientific-thinking becomes something akin to ideology itself.

Philosophy of technology

The philosophy of technology is a sub-field of philosophy that studies the nature of technology. Specific research topics include study of the role of tacit and explicit knowledge in creating and using technology, the nature of functions in technological artifacts, the role of values in design, and ethics related to technology. Technology and engineering can both involve the application of scientific knowledge. The philosophy of engineering is an emerging sub-field of the broader philosophy of technology.